Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

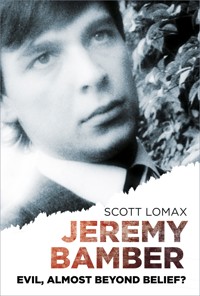

Did Jeremy Bamber murder five members of his adoptive family in a frenzy, or was he falsely imprisoned? In October 1986 Jeremy Bamber was convicted of the murders of five members of his family at their home in Essex. It was alleged he had killed his relatives before staging the scene so that it appeared his sister, Sheila Caffell, had committed four acts of murder before turning the murder weapon, an Anschutz semi-automatic rifle, on herself. The trial judge described Bamber, during sentencing, as being 'warped,' 'callous' and 'evil, almost beyond belief.' Bamber, however, remains adamant he is the victim of a miscarriage of justice. Jeremy Bamber: Evil, Almost Beyond Belief? examines, in great detail, the case of Jeremy Bamber. For the first time all of the relevant information, from both the defence and prosecution cases, is explained. New evidence, only recently obtained, is discussed. Some of the information contained in the book will feature in the defence case when Bamber next appeals against his conviction. It has not yet been made public.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JeremyBamber

JeremyBamber

Evil, Almost Beyond Belief?

S.C. Lomax

First published 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© S.C. Lomax, 2008, 2013

The right of S.C. Lomax to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9630 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Glossary of Terms, Names and Places

Introduction

Chapter 1:

The White House Farm Tragedy

Chapter 2:

The Mind of Sheila Caffell

Chapter 3:

The Official, and the Unofficial, Investigations

Chapter 4:

Jeremy Bamber

Chapter 5:

The Prosecution’s Argument

Chapter 6:

Sheila and Firearms

Chapter 7:

Was There a Motive?

Chapter 8:

Julie Mugford

Chapter 9:

The Blood in the Sound Moderator: Irrefutable Proof of Guilt?

Chapter 10:

The Windows

Chapter 11:

A Break-in at the Osea Road Caravan Park

Chapter 12:

A Violent Struggle in the Kitchen?

Chapter 13:

June Bamber’s Bicycle

Chapter 14:

The Telephone Call

Chapter 15:

Police and Prosecution Malpractice?

Chapter 16:

Proof of Innocence?

Chapter 17:

Conclusion: ‘Justice Will Be Achieved’

A Timeline Indicating the Sequence of Important Events in the Case

Glossary of Terms, Names and Places

Terms

Backspatter – Backspatter occurs when gases, formed when a bullet is fired, expand and create pressure causing blood from a wound to be sucked back towards the barrel of the gun. It has been claimed this phenomenon only takes place when the muzzle of the gun is in close proximity to a victim. It leads to blood entering the barrel and can result in a victim’s blood being transferred onto the person holding the gun.

Baffle plates – circular plates within a sound moderator, which have a hole large enough for a bullet to pass through. The plates reduce the amount of sound produced when a bullet is discharged, by increasing the amount of time it takes for gases produced when the bullet is fired, to be released.

Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) – the organisation established in 1997 to investigate cases of suspected miscarriages of justice. The Commission can refer a case to the Court of Appeal if it believes there is sufficient reason to suggest a conviction is unsafe or a sentence is unnecessarily long.

Firearms discharge residue (FDR) – particles of firearms discharge residue are released from a gun when it is fired.

LCN DNA analysis – Low Copy Number DNA analysis, a very sensitive technique used to replicate DNA so that if even small amounts of the genetic material exist they can be detected.

Ritualistic cleaning – before committing suicide some individuals will wash themselves. This is termed ritualistic cleaning.

Sound moderator – the technical term for a silencer.

Names

Detective Superintendent Mike Ainsley – the detective who replaced Taff Jones as Senior Investigating Officer.

Anthony Arlidge QC – the barrister who led the prosecution counsel at trial.

Jeremy Bamber – the man convicted of the murder of five members of his own family, the subject of this book.

June Bamber – Jeremy Bamber’s adoptive mother, a victim of the White House Farm tragedy.

Ralph Bamber – Jeremy Bamber’s adoptive father, a victim of the White House Farm tragedy.

Sergeant Christopher Bews – one of the first officers to arrive at White House Farm, shortly before Jeremy Bamber, in the early hours of 7 August 1985.

David Boutflour – Jeremy Bamber’s cousin, the son of Robert and Pamela Boutflour.

Pamela Boutflour – June Bamber’s sister.

Robert Boutflour – Pamela Boutflour’s husband.

Colin Caffell – the husband of Sheila Caffell and father of Daniel and Nicholas Caffell.

Daniel Caffell – one of Sheila Caffell’s six-year-old twin sons, a victim of the White House Farm tragedy.

Nicholas Caffell – one of Sheila Caffell’s six-year-old twin sons, a victim of the White House Farm tragedy.

Sheila Caffell – the mother of Daniel and Nicholas Caffell and either a victim or the perpetrator of the shootings at White House Farm.

Brett Collins – Jeremy Bamber’s best friend.

Police Constable Laurence Collins – one of the first members of the Tactical Firearms Unit to enter the farmhouse.

Doctor Ian Craig – the doctor who certified the deaths of the victims of the White House Farm tragedy.

Mr Justice Maurice Drake – the judge who presided over Jeremy Bamber’s trial. He is now Sir Maurice Drake.

Ann Eaton – the daughter of Robert and Pamela Boutflour and therefore Jeremy Bamber’s cousin.

Peter Eaton – Ann Eaton’s husband.

Brian Elliott – a Home Office scientist who provided evidence for the prosecution at trial regarding swabs taken from Sheila Caffell’s hands.

Doctor Hugh Ferguson – Sheila Caffell’s psychiatrist.

Malcolm Fletcher – the prosecution’s ballistics ‘expert’.

John Hayward – the forensic scientist who studied the blood in the sound moderator, a prosecution expert witness at trial.

Detective Sergeant Stan Jones – one of the investigating police officers who suspected Jeremy Bamber of having been responsible for the murders from an early stage in the investigation and who interviewed the suspect when arrested.

Detective Chief Inspector Thomas (Taff) Jones – the original Senior Investigating Officer who was always certain of Jeremy Bamber’s innocence right up until his bizarre death, where he fell a short distance from step ladders, just months before Bamber’s trial.

Professor Bernard Knight – a forensic pathologist called by the defence to show Sheila was capable of the murders.

Doctor Patrick Lincoln – the defence expert witness who was called to give evidence at trial regarding the blood in the sound moderator.

Matthew MacDonald – a man alleged to have been hired by Jeremy Bamber to carry out the murders. He was later found to have no connection with the shootings.

Julie Mugford – Jeremy Bamber’s girlfriend between 1983 and September 1985, the key prosecution witness at trial.

Police Constable Stephen Myall – one of the first officers to arrive at White House Farm, shortly before Jeremy Bamber, in the early hours of 7 August 1985.

Anthony Pargeter – Jeremy Bamber’s cousin on Ralph Bamber’s side of the family.

Liz Rimington – Julie Mugford’s best friend, who told Mugford, on the eve of Mugford having approached the police to implicate Jeremy Bamber in the murders, that Bamber had slept with her.

Geoffrey Rivlin QC – the defence barrister at Jeremy Bamber’s trial.

Police Constable Robin Saxby – one of the first officers to arrive at White House Farm, shortly before Bamber, in the early hours of 7 August 1985.

Victor Temple QC – the barrister who represented the prosecution at the 2002 appeal hearing.

Michael Turner QC – the barrister who represented Jeremy

Bamber at the 2002 appeal hearing.

Doctor Peter Vanezis – the pathologist who conducted the postmortem examinations of the victims of the White House Farm tragedy.

Mark Webster – A forensic scientist called by the defence at Jeremy Bamber’s 2002 appeal hearing to provide his expert opinion regarding the blood in the sound moderator.

Police Constable Michael West – the police officer who answered Jeremy Bamber’s telephone call on the morning of 7 August 1985.

Barbara Wilson – the secretary at White House Farm.

Places

Bourtree Cottage, 9 Head Street, Goldhanger – the home of Jeremy Bamber. The name ‘Bourtree Cottage’ will be used to refer to Bamber’s cottage although Bamber himself never used this name for his home.

Chelmsford Police Station – The station where Jeremy Bamber was taken for questioning.

Osea Road Caravan Park – The caravan park owned (in 1985) by June Bamber, Pamela Boutflour, Jeremy Bamber and Ann Eaton.

White House Farm, Tolleshunt D’Arcy – the Bamber family residence and the scene of the shootings.

Introduction

I was wrongly convicted in 1986 of murdering five members of my family. . . I have protested my innocence through all the usual channels and tried hard to find a successful path to the appeal courts.

(Jeremy Bamber writing in 2002)

During Wednesday 7 August 1985 the media began to report a horrific incident in a small Essex village, approximately thirty-five miles north-east of London. Few people outside the county would have previously heard of Tolleshunt D’Arcy, but the violent deaths of five people, a couple in their sixties, their daughter and her two children, attracted the attention of people all over Britain.

It was a terrible tragedy and the public were deeply saddened when they heard that the police believed that the mother of the two children, Sheila Caffell, a mentally ill woman recently released from a psychiatric hospital, had killed her own offspring as they slept in their beds, then shot her parents before turning the gun on herself.

One month after the deaths, however, Jeremy Nevill Bamber, Sheila’s adoptive brother, was viewed to be the person who killed his family before staging the scene so that the police would believe his sister was responsible. He was arrested twice before being charged with the murders and stood trial at Chelmsford Crown Court in October 1986, when he was just twenty-five years old.

Following a high-profile nineteen-day trial the jury were sent out to begin their deliberations over what was a complex case of forensic science and witness testimony. Unable to reach a unanimous verdict, the trial judge, Mr Justice Drake, informed them that a majority verdict would be acceptable. Bamber was returned to jail overnight, convinced that he would soon walk free. However, the following day, on 28 October 1986, the members of the jury returned to the court and announced a decision Bamber had never anticipated. The foreman of the jury told the court that a guilty verdict, by a majority of ten to two, had been reached for each of the five counts of murder he stood accused of. Bamber collapsed in the dock as he heard the verdict.

When sentencing the condemned man to life imprisonment, with a recommendation that he should serve at least twenty-five years, Mr Justice Drake told Bamber:

Your conduct in planning and carrying out the killing of five members of your family was evil, almost beyond belief. It shows that you, young man that you are, have a warped and callous and evil mind behind an outwardly presentable and civilised appearance and manner.

Recently Bamber has written about his feelings of shock and disbelief when he was convicted for murdering his family:

Although it’s hard to recall exactly what it felt like, what I do remember is that I never heard a word he [Mr Justice Drake] said – I recall the jury giving their verdicts by 10 – 2 majority and then being stunned as if hit by a 10 ton truck. It was as if I’d been knocked unconscious yet still being awake, I just couldn’t believe it to be honest and in such circumstances you go into shock, exactly the same reaction to being told I’d lost my whole family a year earlier – I didn’t believe that either when told by the police, and then the jury saying I was responsible was equally as unbelievable – so listening to what the judge had to say never featured.

Bamber was not the only person who could not understand the situation; a number of those in the courtroom had expected an acquittal and even two members of the jury were seen to be crying as the verdicts were announced.

As the disbelieving convict left the dock to begin a life behind bars, plans for an appeal were begun and since then Bamber’s intention to clear his name has never wavered. However, his continued efforts to persuade the public that what he believes to be a miscarriage of justice has taken place have caused great anger among those who testified against him at trial. Due to the perceived risk he poses, because he was convicted of killing two children as they slept and because he is said to have attempted to point the finger of blame for the violent massacre at one of his other victims, Bamber was told in 1994 that he will never be released from prison. He remains, however, strong in the face of adversity and utterly convinced he will experience freedom once again. He has vowed always to argue against the conclusion that he is a wicked, callous killer and is evil, almost beyond belief, having written in December 2002, ‘Let no one doubt that, in years to come, justice will be achieved and my conviction will be quashed.’ Bamber is either one of the most wicked villains in a British jail or, due to the length of time he has spent confined to a cell, the victim of one of the greatest errors made by the justice system.

Bamber’s trial generated a huge amount of publicity, which gave him a status as one of Britain’s most hated men. The ongoing media interest in his case has allowed his perceived notoriety to develop further.

Bamber has launched two unsuccessful appeals against his conviction. In 1989 the Court of Appeal upheld his conviction stating that there is ‘nothing unsafe or unsatisfactory about this conviction.’

Undeterred he continued to study his case and, in October 2002, he once again entered the Court of Appeal, relying largely upon DNA evidence derived from scientific techniques unavailable at the time of his trial. However, when the judges upheld his conviction, in December 2002, they concluded that:

We have found no evidence of anything that occurred which might unfairly have affected the fairness of the trial. We do not believe that the fresh evidence that has been placed before us would have had any significant impact upon the jury’s conclusions if it had been available at trial. Finally the jury’s verdicts were, in our judgment, ones that they were plainly entitled to reach on the evidence. We should perhaps add in fairness to the jury that the deeper we have delved into the available evidence the more likely it has seemed to us that the jury were right, but our views do not matter in this regard, it is the views of the jury that are paramount.

The facts regarding the evidence presented at the last appeal, in addition to the evidence uncovered more recently, will be discussed in full detail to expose the fact that the prosecution’s argument at trial is being continually eroded, so much so that Bamber’s supporters believe it can no longer be acceptable to say that the conviction is justified. New evidence has recently been uncovered and this will be discussed in this book. The evidence is considered to be significant, particularly that presented in the penultimate chapter, and will form part of the defence case at Bamber’s next appeal hearing. However, does the fresh evidence prove Bamber’s innocence? This is the question I ask you to consider whilst reading what follows.

The weaknesses in the case against Bamber are, he claims, being recognised by an increasingly large number of people across the world, and Bamber now has the support of Members of Parliament in addition to thousands of ordinary members of the public, both male and female, who have expressed concern about the conviction. Many of those who have served in prisons with Bamber including Michael O’Brien, one of the Cardiff Newsagents Three, whose murder conviction was quashed by the Court of Appeal after he had spent eleven years in prison for a crime he did not commit, believe Bamber to be innocent, as do a number of prison officers, former prison officers, officers from Essex Police and former detectives from Essex Police.

Bamber was convicted only by a majority of ten to two, the minimum majority possible to allow a verdict. This shows that there was no overriding proof of Bamber’s guilt, with the jury not being able to agree over whether he was guilty. Had the jury heard all the evidence that was available to the police and prosecution, and should (but was not as will be shown in this book) made available to the defence, then the outcome of the trial could have been very different.

In 2002, when rejecting Bamber’s latest appeal, the judges said:

Our system trusts the judgment of a group of 12 ordinary people to make such assessments and it is not for the Court of Appeal to try to interfere with their assessment unless the verdicts are manifestly wrong, or something has gone wrong in the process leading up to or at trial so as to deprive the jury of a fair opportunity to make their assessment of the case, or unless fresh evidence has emerged that the jury never had an opportunity to consider.

Members of the jury are ordinary people who are rarely educated in law and forensic science. It is therefore a cause for concern that the present jury system is used in this country. The case of Jeremy Bamber is very complex and it is even more complex now with the most recent evidence having been uncovered. In complex cases it is appreciably difficult for juries, which are composed of ordinary members of society randomly selected, to fully understand all the facts. A number of miscarriages of justice take place because juries do not fully understand the evidence. At present even those with limited intelligence can decide a person’s fate. The system would be less prone to error if an intelligent jury were selected.

In many trials heard in courts across the globe, particularly those where a defendant or defendants are accused of serious crimes such as rape or murder, forensic evidence forms a significant part of the discussions. Forensic scientists were required to argue about their views regarding forensic evidence believed to be relevant to the crimes for which Bamber stood trial. Whenever forensic evidence is presented in court the prosecution and defence commission experts to attempt to argue whether the evidence proves the guilt of the defendant or defendants. If experts in forensic science cannot agree over the significance of forensic evidence then how can a lay jury, comprised of twelve individuals, understand the evidence they have to listen to in order to reach the correct verdict?

The truth is that a trial is little more than a stage show whereby prosecution and defence counsels perform, with a jury voting at the end as to whom they believe provided the most plausible performance. A verdict is an opinion expressed by twelve individuals who decide whether or not they believe the prosecution’s theory. If a jury does not understand all the information provided at trial, and it must be remembered that jurors are not provided with an opportunity to ask questions whilst evidence is being heard, or if it does not hear all the relevant information, then their verdict will not always reflect the truth.

The following chapters will demonstrate that the jury at Bamber’s trial did not hear all of the facts they required to make a fully informed decision as to the defendant’s guilt. This of course, does not necessarily mean the jury reached the wrong verdict. Did the ten members of the jury, who thought Bamber to be guilty, believe the truth or were the two dissenters correct in their assertion that Bamber’s guilt could not be proven?

This book will show that contrary to popular belief there was no evidence proving Jeremy Bamber’s guilt in this strange case, which he maintains is a ‘mystery filled with many conundrums.’ Instead, a chain of circumstantial evidence was constructed to paint a picture that Bamber was capable of killing his own relatives, but was that picture an accurate reflection of the truth? The following words of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle should always be remembered when one decides whether a chain of circumstantial evidence can be used to prove guilt:

. . . it must be confessed that circumstantial evidence can never be absolutely convincing, and that it is only the critical student of such cases who realises how often a damning chain of evidence may, by some slight change, be made to bear an entirely different interpretation.

When reading what follows, keep the above words in mind. The prosecution claimed that all the evidence they presented pointed to absolute proof of Bamber’s guilt. However, could there be a more innocent explanation that suggests a miscarriage of justice could have taken place? Or were the police and prosecution correct in their assertion that Bamber is an evil murderer?

In writing this book I have had access to the vast majority of the documentation relevant to this case, including transcripts from the trial and appeal hearings, the reports commissioned from experts and the statements provided by witnesses. Documentary and photographic evidence, which substantiates what Bamber has always claimed to be the truth, has been presented to me. This evidence will be discussed in this book, some of it being aired for the very first time, and will bring the case right up to date. The book also includes many exclusive statements from Jeremy Bamber himself, taken from extensive private interviews and my correspondence with him over the past six years.

I would like to make it clear from the outset that whilst Jeremy Bamber is aware of this book, he has not influenced the writing of any part of it. The views expressed in the following chapters are my own and reflect the independent beliefs I have regarding this case, beliefs acquired only through my own research of the evidence, in addition to my own observations, and not the words of Jeremy Bamber or any of his supporters. Indeed, Bamber disagrees with certain opinions I have about the case. Essex Police were contacted in the hope that they would be able to offer their explanations for the new evidence and cooperate in the writing of this book. However, the police declined to comment on any issue involved in the case, in light of the fact that the Criminal Cases Review Commission is undertaking a review of the evidence. Nonetheless, this book will present the cases for both the defence and prosecution, with reference to the views of the police being made where I know their views. It will provide sufficient information to allow readers to reach their own conclusion as to whether or not Jeremy Bamber did murder five members of his own family and whether the words ‘Evil, almost beyond belief’ can indeed be applied to him.

CHAPTER 1

The White House Farm Tragedy

Please come over. Your sister has gone crazy and has got the gun.

(The words allegedly spoken to Jeremy Bamber alerting him to the situation at White House Farm)

When Police Constable Michael West picked up the telephone at Chelmsford Police Station, just before 03:20 on the morning of 7 August 1985, little could he have known that he would be involved in one of the most controversial cases in British criminal history.

The caller identified himself as Jeremy Bamber, of 9 Head Street, Goldhanger, and, in a concerned, worried manner, immediately told the officer the reason for his call:

You’ve got to help me. My father has rang me and said ‘Please come over. Your sister has gone crazy and has got the gun.’ Then the line went dead.

Bamber told West that his sister, Sheila Caffell, had psychiatric problems and that there were a number of firearms within the family home, named White House Farm, which is located in the village of Tolleshunt D’Arcy, three miles from Goldhanger. West contacted a colleague, Malcolm Bonnet, who worked as a civilian member of staff in the Information Room at Essex Police Headquarters, by radio, to request a vehicle attend the scene. When he resumed his conversation with Bamber, West could sense the increasing concern in the caller’s voice, with Bamber asking why it was taking the police so long to address his worries. At the end of the conversation Bamber was asked to meet the police at White House Farm, because there was already a police car in the general area of Tolleshunt D’Arcy and so it was easier to meet at the farm rather than for Bamber to be picked up.

It should be pointed out from the outset that at trial it was claimed Jeremy Bamber lied about receiving a telephone call in the early hours of 7 August. In 1985 there were no records available to show when calls were made. However, for now it is important to read what Bamber claims occurred before discussing the tragedy.

It is a fact that Sheila Caffell had ‘gone crazy’ numerous times over the years before August 1985. However, on these occasions Social Services and the family had always been able to resolve the issue without having to involve the police. It is indisputable that Bamber had been contacted in the past to help deal with Sheila, and that the police had never been needed. As the alleged call had been abrupt, and a gun referred to, however, Bamber was concerned and so he tried to call his father back twice, but both of his attempts were met with the engaged tone. Unable to make contact with White House Farm, Bamber phoned Chelmsford Police Station as a precaution. He claims the reason he did not dial 999 was that he feared the possible consequences of the arrival of police cars with their lights flashing and sirens in use. Bamber was unsure if the situation necessitated a police presence and did not wish to make what was perhaps a manageable situation into a dangerous one. He realised though that the presence of one or two police officers could possibly be of use in calming Sheila. However, he admits, ‘Of course in hindsight this tactic seems daft but I was not to know how things were to develop.’

After telephoning the police Bamber contacted his girlfriend, Julie Mugford. He claims he did so because he was unsure as to whether or not he had taken the correct action by involving the police in what he believed was simply a domestic incident without violence. He was concerned that he might cause embarrassment if the police arrived at the house only to find that no threat had been posed. Although his girlfriend had tried to reassure him by telling that there was nothing to worry about, Bamber was still concerned and, after grabbing a jumper, he drove from his cottage to White House Farm.

Whilst driving towards his parents’ home a police car (Charlie Alpha 7) travelling to the same destination overtook Bamber. It was claimed at trial, by one of Bamber’s cousins, that Bamber was a ‘very, very fast driver.’ It was therefore asked why he was driving so slowly that he could be overtaken, particularly if he feared for the lives of his family. However, Bamber has responded to this by saying he was driving at the maximum speed limit and that it was the police who were exceeding that limit, which sounds a plausible explanation. After all, do not the police normally travel beyond the limit when responding to calls where it has been said firearms might be used? It would have been rather embarrassing for Bamber to drive above the speed limit, to be seen to do so by the police who he knew would be on the same road, and arrive at the farm only to find that such haste was unnecessary. Bamber could not know that his family were in danger and he had only called the police as a precaution.

It is easy to use hindsight and say that he should have driven faster. However, if innocent, how could he have known his family would be killed? It is all too easy to say what people should have done but, without being in that particular situation, how can we possibly judge whether or not a person reacted in a natural manner? The same argument can be presented to those who criticise Bamber for not having dialled 999. Bamber says that if the emergency services had been required, Ralph would have contacted them himself and the fact he did not suggests at that point in time the situation had not developed to be so serious that outside help was required. It should be considered that Police Constable West at first seemed reluctant to help Bamber and even afterwards was slow to respond. Therefore even the police originally did not consider the situation to be an emergency during the early stages of the call.

Jeremy Bamber arrived at the junction of Pages Lane, which is the lane leading up to White House Farm, and Tollesbury Road soon before 03:45, shortly after the first police officers to attend the scene had arrived. The police believed Bamber arrived between three and four minutes after their own arrival, which may or may not be an accurate reflection of the time. Unless the officers looked at their watches, there is no way they could appreciate the amount of time that had elapsed and they were not even asked about the time until a number of weeks had passed. Studies have shown that people naturally overestimate periods of time.

The police had parked ten yards in from the road and were waiting for Bamber to turn up. Bamber parked his Vauxhall Astra nearby and walked over to meet the officers, Sergeant Christopher Bews, Police Constable Stephen Myall and Police Constable Robin Saxby. During a brief conversation with Bews it was agreed they should drive near to the farm cottages, approximately two hundred metres from White House Farm, and park their vehicles at that location. After doing this, Bamber accompanied Bews and Myall on a walk up to the farmhouse, whilst Saxby remained in the vehicle to man the radio.

The lights upstairs and in the kitchen of the farmhouse were switched on, but the rest of the house appeared, from the outside, to be in darkness. British Telecom would later, at 03:56, carry out a check on the telephone line within the farm. The check confirmed there was a telephone off its hook and therefore the telephone line was open and could be used to monitor what was happening within the building. At that moment in time nothing could be heard other than the distressed barking of the family pet, a shih-tzu dog named Crispy. However, soon after approaching White House Farm Bamber, Bews and Myall saw a figure moving within the building, inside the upstairs main bedroom. At this point in time, fearing that a siege situation was unfolding, they all ducked behind a hedge, and then ran two hundred metres up Pages Lane, to where the vehicles were parked, in order to assess the situation.

Bamber was asked again about his father’s call, to which he gave the same response as he had when speaking with Police Constable West. He also provided details about his sister’s mental health issues. Sheila’s state of mind will be discussed in the following chapter but it is important to say here that Bamber told the police that his sister suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and that she had not been taking her medication. On both counts, as will be shown, he was telling the truth. Sheila had, at the end of March that year, he explained, been discharged from St Andrew’s Hospital in Northampton, where she had been undergoing treatment.

He added that there had been an argument the previous evening, which he thought might have upset Sheila and caused her to react in such a way that she might pick up a gun. Even so, Bamber did not believe his sister would commit a crime. Instead he thought that she would only use it as a scare tactic, whilst upset.

Bamber gave details about the guns within the house; as on most farms there were a number of firearms inside, including rifles and shotguns. Bamber recalled having loaded an Anschutz .22 calibre rifle on the previous evening whilst working at the farm. He told how he had seen some rabbits, earlier in the evening, beside the Dutch barn so he took the gun to shoot at them if they were still there. However, upon returning to the barn he could not see any rabbits and so he did not fire the rifle. Instead he claimed he placed it on the settle in the kitchen, leaving the box of cartridges beside the telephone. It was common, habitual behaviour, he claimed, for guns to be kept around the house because normally Sheila Caffell and her children were not staying.

Bamber was asked to draw a map of the interior of the building, indicating the positions of doors and windows and labelling where each individual slept.

The head of the family, Ralph Nevill Bamber, was sixty-one years old when he met his death. He is frequently referred to by his middle name, Nevill. I shall, however, refer to him as Ralph because this is how he is referred to by all of those I have corresponded with. A farmer and local magistrate, Ralph had amassed a considerable wealth for himself and his family. A number of businesses had been established and acquired, although the Bamber family did not, in some cases, own the whole company, instead owning a significant share. The Bamber estate was worth, in 1985, approximately £438,000 (at today’s value it would be a multi-million pound mini business empire). As Ralph was a local magistrate he did not want his daughter’s illness and erratic behaviour to be publicised for fear of the family name, and his reputation, suffering as a consequence. This is one reason why the police had never before been contacted; Ralph liked to keep the problems in the family wherever possible.

It was in 1949 that Ralph, a former RAF fighter pilot, married June Bamber, the daughter of a wealthy farming family, and the following year they took up a tenancy at White House Farm. June was also sixty-one years old at the time of the White House Farm tragedy. She was a deeply religious woman to such an extreme that she too had required psychological help.

Ralph and June Bamber, who were unable to have children of their own, had adopted both Jeremy Bamber and Sheila Caffell from the Church of England Children’s Society. Sheila had been adopted in 1958, at the age of seven months, and was twentyeight years old in August 1985.

A former model nicknamed ‘Bambi’, Sheila had married Colin Caffell in 1977, although their marriage had broken down and they had divorced in May 1982. The couple had twin sons, Nicholas and Daniel, who were six years old at the time of their deaths. Sheila and her sons had, on 4 August, moved into White House Farm to stay for a week.

After assessing the situation it was deemed necessary to order the presence of members of the Tactical Firearms Unit, who arrived at the scene at approximately 04:58. Shortly afterwards, whilst outside the building, Bamber told Sergeant Douglas Adams, one of the firearms officers, of the importance of his family, ‘What if anything has happened in there? They are all the family I’ve got.’

Those who lived near to the farm were instructed to remain indoors whilst more firearms officers arrived at the scene. It was decided that no action should be taken until daylight and so, despite the sun having risen nearly two hours earlier, it was not until 07:30 that the police used a sledgehammer to batter down the door and gain access to the building. Four armed officers charged in whilst being covered by colleagues who remained outdoors. The remains of a massacre greeted them.

Ralph Bamber’s body was found downstairs in the kitchen. He was positioned on his favourite chair; face down in a coal scuttle. It seems almost without doubt that the killer moved Ralph’s body into this position because he was perched on the end of the arm of the chair, which had been turned upside down. He was wearing his pyjamas when he had been shot eight times. There were two wounds to the right side of his head and two at the top of his head, which together must have caused an immediate loss of consciousness if not immediate death. Additionally there was a wound to the left side of his lip and a further wound located at the left part of his mandible, which had caused serious fracturing of the jaw, his teeth and had also caused damage to tissue in his neck and larynx. There were also gunshot wounds to the left shoulder and a grazing wound above the left elbow. The two injuries to his left arm would have completely prevented it from being used in any way. The six wounds to the head had been caused when the rifle had been only inches from Ralph’s head. The injuries to his shoulder had been sustained when the rifle was fired from a distance of at least two feet. There were only four spent cartridges in the kitchen, suggesting Ralph had been shot elsewhere before making his way to the kitchen. There was a cartridge on the stairs leading to the kitchen, which shows that he had been shot from this location, and also three cartridges in the main bedroom, which could not be attributed to the other victims. It would seem that Ralph was therefore shot in the main bedroom and then fled to the kitchen where he was killed. At some stage, for reasons that will probably never be known, Ralph’s pyjama bottoms were pulled down to his knees.

Other injuries upon Ralph’s body included black eyes and a broken nose, bruising to his cheeks, lacerations to the head, bruising to his right forearm, bruising to his left wrist and forearm and three circular burn type marks on his back. The injuries were considered consistent with him having been struck by a long blunt instrument, quite probably the rifle used in the shootings.

The telephone, which was located in the kitchen, was off the hook and so it seemed that perhaps Ralph had made a telephone call for help, shortly before being shot, or that his assailant had taken the phone off the hook so that the line could not be used.

June Bamber was located upstairs, in the main bedroom. She had been shot seven times; once as she lay in bed and six times as she moved towards the bedroom door in her attempt to escape. Two of the wounds were to the head, with one shot having been fired between the eyes. These would have caused almost immediate death. It is possible that when shot between the eyes, the rifle had been in contact with June Bamber. Although this would later be deemed unlikely, it is certain that the shot was fired from very close range.

The twins had both been shot in the head as they lay in their beds; Daniel had been shot five times in the back of his head and Nicholas had been shot three times. It was assumed that both had died in their sleep. Four of the five injuries sustained by Daniel had been caused when the rifle was within one foot of his head. The wounds inflicted on Nicholas were fired from a much closer range and it is possible they were contact shots. This was unnecessary violence perpetrated by someone with hatred for the children or by someone with diminished responsibility.

Sheila was found on the floor of the main bedroom, beside her parents’ bed. Sheila’s own bed had not been slept in that night. She had sustained two gunshot wounds to the throat; post-mortem examination confirmed that she could have been alive and conscious for a period of time after receiving the first wound. This wound had been created when the rifle muzzle was within a distance of three inches, but it had only penetrated the soft tissue. It was the second shot that killed her, by causing significant injury to the base of the brain, when the muzzle was in contact with Sheila’s throat. Sheila had no defence injuries and therefore it was unlikely she had fought with, or even put up any resistance against, any attacker. This is unusual given that she was shot whilst on the floor; therefore if she died at the hands of another individual she must have cooperated fully. However, in the opinions of those who saw Sheila’s body it appeared to be a case of suicide, for her fingers were clutching an Anschutz .22 semi-automatic rifle, which lay on her chest.

It was later claimed that Bamber did not show emotion or act in a way that would be expected for a man who had lost his family, being able to eat a full cooked breakfast hours later that morning. This is untrue however; Bamber could hardly stop crying and he entered a state of shock, failing to understand what had happened. It has been said that at one point he accused the Tactical Firearms Unit of accidentally killing his family when they rushed into the building. Earlier, despite being told of the deaths, he repeatedly pleaded with Chief Superintendent Harris to allow him to speak to his father, unable to comprehend that all his family had been killed. After a while of talking with the doctor who had been called to certify the deaths, Doctor Ian Craig, Bamber was seen to stagger, still in a state of severe shock, into a field where he vomited.

It is true that at times Bamber appeared calm, but the reality is that he was anxious but did not believe there would be anything to worry about once the situation was resolved. Bamber himself says:

The reason I was calm was that I had no idea about what had or was about to take place in the house and felt with the police there that we could control the situation and resolve matters with a happy ending.

Bamber believes it is odd that the police considered his calm manner to be suspicious. It is his opinion that it would be highly difficult for a man who had just killed his family to be very composed whilst in the company of police officers who could, at any point in time, realise that he might be a cold blooded murderer.

The police had promised Bamber that no one would be hurt and that all would be well. This resulted in him being calmer, though he was still concerned and so the officers had tried to talk to him about other things, such as his interests. When being told of the deaths Bamber was upset and asked how his family could have been killed when the police had promised him that everything would be fine.

The police immediately accepted they were dealing with a case of four murders, with Sheila having committed the crimes, before having committed suicide. They believed this because of the evidence at the scene, Jeremy Bamber’s account of events which he had provided to the officers he had spoken to, and the knowledge of Sheila Caffell’s mental illnesses.

The information relating to Sheila’s psychological well-being, and other relevant information, is of fundamental importance and will be discussed in the following chapter.

CHAPTER 2

The Mind of Sheila Caffell

If it wasn’t me then there is nothing against Sheila being responsible and everything to say she was.

(Jeremy Bamber writing in August 2003)

Whilst outside White House Farm in the early hours of 7 August 1985, Bamber was asked whether it was likely his sister could have gone berserk with a gun, to which he replied, ‘I don’t really know. She is a nutter. She’s been having treatment.’ If Bamber had calculated a plan to use Sheila’s illness to create the false impression she was a murderer, it would be expected that he should wish to blame Sheila from a very early stage. Indeed he has been accused of having blamed Sheila from the outset. Whilst it is true that he had claimed Sheila had a gun and had ‘gone crazy’, the knowledge of which he claims to have come from his father’s alleged telephone call, the words ‘I don’t really know’, surely suggest that he was unsure as to the situation rather than executing a plan in which he would use Sheila as a scapegoat for his own murders.

Sheila had been under treatment for severe psychological problems for a number of years. When her marriage with Colin Caffell broke down, she entered a state of depression and eventually began to suffer from acute paranoid schizophrenia. On two occasions she had been admitted to St Andrew’s Hospital in Northampton, a psychiatric hospital, because of her condition which made her potentially dangerous to herself and others.

Schizophrenia is a severe mental illness, the sufferers of which experience delusions and hallucinations. Patients will have mood swings, sometimes feeling depressed and on other occasions seeming immensely happy and full of energy. A lack of concentration, a feeling of guilt and suicidal thoughts are indicative, in many cases, of a schizophrenic episode. Furthermore the illness is responsible for causing bizarre behaviour and disordered thinking; schizophrenics will irrationally believe that carrying out strange actions will achieve their goal. Sufferers of acute schizophrenia do experience sudden onsets of severe psychotic symptoms. Psychotic symptoms include hallucinations, an inability to separate real from imaginary experiences (which often leave the sufferer confused and frequently frightened), social isolation and withdrawal, and unusual speech, thinking and behaviour. Sufferers of paranoia are often suspicious, defensive and hostile. They believe that others are a threat to them but the reactions to a perceived threat vary between sufferers. Those who have been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia will often irrationally believe they are being persecuted or that people are plotting against them. Whilst the majority of those who suffer from paranoid schizophrenia do not exhibit violent behaviour, if their medication is stopped, or the effect of the medication is diminishing, there is an increased risk of them harming people, particularly family members in their home. Suicide is more common among young schizophrenics, especially when medication is stopped, or the effect of the medication is diminishing. Bear this information in mind when reading what follows in this chapter.

Sheila had issues with the concepts of good and evil. She would frequently believe she had been given the responsibility of eradicating the world of evil. Indeed on 30 March 1985, on the day after she was released from hospital where she had been undergoing treatment for her illness, Sheila told Helen Grimster, a distant relative aged fourteen years old, that she was a white witch who had been asked to perform the task of ridding the world of all evil. She also asked Grimster if she had ever contemplated suicide, adding that she had frequently considered ending her life. Grimster was very frightened by Sheila’s behaviour. Sheila was considering joining CND with the intention of solving the world’s problems, but her main concern was to fight against those she believed to be evil on a much more local scale.

Psychiatric reports noted that Sheila’s illness was centred on her children whom she referred to as ‘the Devil’s children’. She believed that the Devil had possessed her and had given her the power to carry out his evil. Sheila had a strong belief she could project evil to others. Bizarrely she had major concerns that her children would have sex with her and carry out violent actions upon her. Sheila’s psychiatrist, Doctor Ferguson, wrote in his report that his patient self-harmed, had expressed thoughts of a suicidal nature and told that she was capable of murdering her sons. Sheila had told Ferguson that she needed to be exorcised, to remove the Devil from her body, and if this could not be done then she would have to die. Bamber claimed on one occasion Sheila had punched one of the twins in the face because a conversation had been interrupted. Mr Justice Drake, however, in his summing-up, told the members of the jury Sheila had no reason to harm or kill her children. Was this true? In addition to her thoughts relating to her children, whilst in hospital Sheila had made it clear that she often had disturbing thoughts relating to June Bamber. Just one month before the tragedy Sheila had asked her doctor, Doctor Myrto Angeloglou, if her monthly dose of Haloperidol could be halved so that the drowsy side effects could be eliminated. Haloperidol is an anti-psychotic drug, used to control a patient’s state of mind. The only drugs in Sheila’s blood and urine samples, taken during her post-mortem, in addition to Haloperidol, were a drug used to combat the side effects of Haloperidol, and cannabis; a drug that in recent years has been shown to induce schizophrenic episodes. Sheila was also known to take cocaine although traces of this drug were not detected.

At trial it was claimed that Sheila had no reason to kill her parents. She had, according to prosecution witnesses, nothing but love towards her father whom she had great respect for, although her dislike for her mother was told to the court. June and Sheila had a very troubled relationship and Sheila would often tell those she knew about the difficulties which mainly related to June’s dissatisfaction regarding her daughter’s ‘immoral’ behaviour. Sheila’s dislike for her adoptive mother had resulted in a quest to find her natural mother, whom she did successfully trace in 1982. This was before Sheila’s mental health deteriorated. With her psychiatric problems came a worsening relationship with June. Sheila believed that both June and herself had evil minds and needed to be cleansed. It was claimed, however, that even though Sheila and June disliked one another Sheila would not have killed her mother. The defence argued Sheila might have had no choice but to kill her parents who would have stood in the way of her irrational intention to kill her children and commit suicide.

The defence were able to show that Sheila’s love for an individual did not prevent her from becoming violent towards that individual. One of Sheila’s former boyfriends, Freddie Emami, had told the police how on one occasion, just months before the murders, Sheila had become:

like someone possessed, ranting and raving. She was striking herself and beating the wall with her fists. I tried to calm her but she didn’t seem to hear me. I became extremely frightened, not only for her but for me.

On this occasion Sheila had, for some reason, become convinced the CIA were bugging her telephone line, listening to her calls. Sheila would frequently experience feelings that people were listening to her. She believed that others could read her thoughts and this caused a great deal of pain for her. The incident witnessed by Freddie Emami, whom Sheila believed had become possessed by the Devil, was so serious that Sheila was admitted into a psychiatric hospital as a direct consequence.