9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

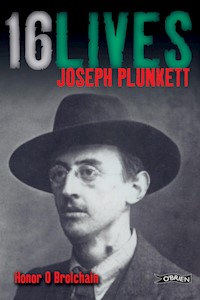

Joseph Mary Plunkett (1887-1916) from Dublin was one of the leaders of the 1916 Rising, the designer of the military plan and the youngest signatory of the Proclamation. A recognised poet, he was already dying of TB when, aged 28, he married Grace Gifford in Kilmainham Gaol, just hours before he was exectuted on May 4th, 1916. This timely biography, written in an entertaining, educational and assessible style and including the latest archival evidence, is an accurate and well-researched portrayal of the man and the uprising.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Reviews

The 16LIVESSeries

JAMES CONNOLLYLorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLINBrian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETTHonor O Brolchain

ROGER CASEMENTAngus Mitchell

THOMAS CLARKELaura Walsh

EDWARD DALYHelen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTONJohn Gibney

SEÁN MACDIARMADABrian Feeney

ÉAMONN CEANNTMary Gallagher

JOHN MACBRIDEWilliam Henry

WILLIE PEARSERoisín Ní Ghairbhí

THOMAS MACDONAGHT Ryle Dwyer

THOMAS KENTMeda Ryan

CON COLBERTJohn O’Callaghan

MICHAEL O’HANRAHANConor Kostick

PATRICK PEARSERuán O’Donnell

DEDICATION

For my son and daughter, Mahon and Isolde Carmody.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Assembling historical information is like making a jigsaw out of jelly; each piece disappears into the whole which, in turn, grows bigger and wider. Often it is the very small pieces which make the difference and often they are handed on with great generosity by people who have a real awareness of their value. I have experienced this generosity over and over again and would like to thank all those who offered ideas, facts, anecdotes and documents for this book. This includes those who donate information to the World Wide Web, often without knowing whether it is being used or appreciated.

The following people contributed substantially to the process:

Dr William J. McCormack, the late Donal O’Donovan, James Connolly Heron, Paul Turnell, Art O Laoghaire, Major General (Rtd.) David Nial Creagh, The O’Morchoe, Charles Lysaght, Maeve O’Leary, Jenny and Andrew Robinson, Dr John O’Donnell and Michael O’Donnell, David Lillis, Mary Plunkett, Dr Carla Keating, Dr Anne Matthews, Henry Fairbrother, David Kilmartin, Anna Farmar, Lucille Redmond, Muriel McAuley, Seosamh O Ceallaigh, Grainne Nic Giolla Chearr and Alice Nic Giolla Chearr, Patrick Cooney, Terry Baker, the O’Brien Press team, especially Helen Carr, Lorcan Collins and Ruán O’Donnell.

The following institutions and their curators were, as always, crucial, helpful and civilised: the National Library of Ireland, especially the Reprographic Services who were exceptionally helpful, University College Dublin Archive, and very special thanks to the Internet Archive, the Digital Library of Free Books; the Defence Forces, Ireland, Bureau of Military History; Stonyhurst College Archive, Archivist: David Knight; Catholic University Schools Archive, Archivist: Kevin Jennings; Belvedere College Archive, Archivist: Tom Doyle.

I must also mention two organisations which are personal enablers in my professional life, the National Council for the Blind of Ireland and Irish Guide Dogs for the Blind.

As often happens there is one person who must take the lion’s share of thanks: my husband, Brendan Ellis, has, from the beginning, been a major part of all the processes from dictating about one thousand documents to me to store for use on the computer, taping documents, reading, researching and, in the final stages, reading and proofing the manuscript and offering positive and negative criticism. Inestimable, unquantifiable and always kindly done!

16LIVES Timeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement, founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September. Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07. Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Prime Minister Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors’ Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eoin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm. The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm. The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork harbour.

22 April, 9.30am. The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eoin MacNeill as Chief-of-Staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am. Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon. Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVESMAP

16LIVES - Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell, 16 LIVES Series Editors

CONTENTS

Reviews

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. 1886-1902 The Young Plunketts

2. 1902-1906 Country Life

3. 1906-1908 Stonyhurst

4. 1908-1910 Many-Sided Puzzle

5. 1911 A Social Life

6. 1911-1912 Algiers

7. 1912 Algiers, Dublin, Limbo

8. 1913 The Good Life and The Review

9. 1913 The Lockout and the Peace Committee

10. 1913-1914 A Long-Awaited Force

11. 1914 Words, Actions and War

12. 1915 To Germany Through the War

13. 1915 Decision and Command

14. 1915-1916 Passion and Plans

15. 1916 Brinks of Disintegration

16. 1916 Rising and Falling

17. 1916 The Dark Way

Appendix

Endnotes

Sources

Index

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

Introduction

JOSEPH PLUNKETT – eldest son of a Papal Count, afflicted with tuberculosis from early childhood, poet with religious elements whose middle name was Mary – could not have been expected to press his name into history as one of the seven leaders of a revolution and the youngest signatory to its philosophy, but he was and he did. In searching for the real person for this book it was mostly his own writing that rescued his reputation. It revealed the lively mind, the talents and the humour of the very young man in his diffidence and arrogance and in the more mature man, the same characteristics, but more serious, philosophical and humane.

Writer, traveller, reader, experimenter, roller-skater, thinker, crackshot, dancer, lover of women, theatre company director, motorcyclist, actor, editor, philosopher, military tactician, linguist, negotiator and, with all these, talkative, kind, critical and affectionate. This was the Joseph Plunkett who emerged, the man who cheated impending death from tuberculosis, dying instead by firing squad at the age of twenty-eight.

From his late teens he took the writing of poetry seriously and worked very hard at it. Fortunately, he put a date on anything he hoped to have published and when inserted into the story of his life they sit well there, sometimes giving us an insight into his life and sometimes having no apparent relevance at all.

His diaries leave a sense of having met someone and begun to know them and this is part of the great reward of working with him. His variety of passions, his insistence on thinking ideas through and his thread of humour through everything make him a fascinating and surprising discovery and one who deserves a completely new public image.

Honor O Brolchain

CHAPTER 1

• • • • • • •

1886–1902 The Young Plunketts

WITLESS

When I was but a child

Too innocent and small

To know of aught but Love

I knew not Love at all.

But when I put away

The things I had outgrown

I learnt at last of Love

And found that Love had flown.

Now I can never find

A feather from his wings

Though every day I search

Among my childish things.

Joseph Plunkett

When George Noble, Count Plunkett and his wife returned from their two-year American honeymoon in 1886 Josephine Mary (Countess Plunkett) was already pregnant with their first child. The Plunketts were the beneficiaries of wealth created by their hardworking parents. Their fathers, Patrick Plunkett and Patrick Cranny, had moved from the leather and shoe trade in nineteenth-century Dublin to building on the south side of the city, largely thanks to money provided by their wives, one of whom, Bess Noble Plunkett, had a shop of her own and the other, Maria Keane Cranny, had family money, a dowry. The property built and accrued by Plunkett and Cranny would have come to a considerable amount. It was mostly not intended for sale, but for rental to professionals and civil servants. Count and Countess Plunkett’s marriage settlement included eight houses on Belgrave Road, Rathmines and seven houses on Marlborough Road in Donnybrook, three farms in County Clare and a house on Upper Fitzwilliam Street, No. 26, ‘an address suitable for a gentleman’, and this house was where they lived.

It was comparatively narrow and consisted, essentially, of two rooms on each floor. The basement was mostly used and occupied by the servants, but there was also a lavatory there for Count Plunkett’s exclusive use. On the hall floor Count Plunkett had his study in the front beside the hall door to which he retreated for most of the time when he was at home to continue his work on European Renaissance art, Irish history and politics and his many other areas of scholarship and expertise. Behind his study was the dining room with the painting he thought might be a Rubens over the mantelpiece and behind that room a conservatory. From the hall the elegant staircase led past a beautiful window to a landing and two drawingrooms in an L-shape, all designed and proportioned by the Georgian builder for stylish entertaining. The stairs continued past a bedroom on the return to the two bedrooms on the next floor, one for the Count and one for the Countess. From this floor upwards the style and elegance disappeared and a very ordinary and very steep attic-type stairs led to the nurses’ and children’s quarters, which had a bathroom used by most of the household as well as one room the width of the front of the house and one, half that, at the back. The area behind the house, a garden and yard, was very small in modern terms, not a leisure garden, but an area for the burying and disposal of waste. Behind this was Lad Lane where the Plunketts’ carriage was housed and their horses stabled in the livery stables. Count Plunkett filled the house all the way to the nursery at the top with paintings. He also oversaw the decoration of the drawingrooms and cast the house as a place beautiful enough for children to grow up in, but in the forty years they occupied it the Plunketts did no more to improve or decorate it.

The nursery area at the top of the house was home not only to that first baby, Philomena Mary Josephine (Mimi) and her nurse from Mimi’s birth in 1886, but to all seven children as they arrived, their three nurses and one or two nursemaids until they were all young adults. This does not in the least compare with the four or five entire families in one room which occurred in the terrible and extensive poverty of areas of Dublin at the time, but it must have made some of the individuals in those two rooms ache for peace and privacy at times. It was alleviated by visits to the rest of the house to see their parents once a day or less and a walk every day:

One or two of the nursemaids used to bring all of us children for a walk every day but before we could leave there were seventy little buttons to be done up on my clothes. The walk was always the same, from Fitzwilliam Street along Leeson Street and Morehampton Road to Donnybrook Church and a little way on to the Stillorgan Road, with Jack in the pram and the two small ones, George and Fiona, in a mailcar which was a back-to-back go-car made mostly of bamboo. I had to walk with Joe and Mimi and Moya. Geraldine Plunkett Dillon

All seven children were born in the house: Philomena Mary Josephine in 1886, Joseph Mary in 1887, Mary Josephine Patricia in 1889, Geraldine Mary Germaine in 1891, George Oliver Michael in 1894, Josephine Mary in 1896 and John Patrick in 1897, their mother being attended each time by Nurse Keating, her maternity nurse. Countess Plunkett’s name, Josephine Mary, is repeated with incongruous frequency in the children’s names but, in fact, they were usually known as Mimi, Joe, Moya, Gerry, George, Fiona and Jack. Thirteen months after Mimi, on 21 November 1887, Joe (Joseph Mary) arrived.

The year after the birth of the next child, Moya, in 1889 the Countess organised the first of her famous holidays. These were as much to get away from her children as to get away herself. This one was to Tuam in County Galway where she rented an unfurnished house and had all of the luggage and furniture sent there from Dublin by canal boat to Ballinasloe and from there, in thirty carts, to Tuam. She travelled there with Mimi, Joe and Moya, all under five years old, but she herself spent most of the time back in Dublin leaving the children in the care of their nursemaids and the owner of the house. Joe’s sister, Gerry, was born four years after Joe, in November 1891, and it is to her that we are most indebted for the detailed personal accounts of the lives of all her family, especially Joe, whom she greatly loved.

One of her very early memories was a ‘howling row’, a battle between Mimi and Joe and the ‘horrible’ head nurse. Mimi and Joe told her years later that they were just trying to draw attention to what was going on. They were at the mercy of this nurse and her threats. Joe told her that one of the nurses used to heat the poker until it was glowing red and threaten to shove it down his throat when he cried. Another trick was to push the go-car (precursor of the buggy) out over the edge of the canal and threaten to let go; this was supposed to be for ‘fun’. Gerry’s nurse (each child had a nurse brought in for them) Biddy Lynch was different. She stayed with them for nine years bringing order, affection and pleasure into their lives. In Gerry’s description:

She was kind, sensible, just, clever, intelligent, patriotic (a Parnellite), absolutely reliable, religious, scrupulously exact and honest. She taught us to read and to write and to sing Irish songs, she taught us our religion, she washed us and dressed us, she made our clothes and hats and, in her spare time, knitted stockings for her mother at home in County Westmeath.

Some of the maids lived in, but those who didn’t used to finish work at about seven o’clock in the evening and meet up with their friends, often standing and chatting outside the house. On one of these evenings Joe and George decided to drop light bulbs from the fourth floor nursery window onto the basement area and the maids thought the resulting explosions were revolvers. They complained that they knew they had been noisy, but they didn’t think they should be shot at!

Joe already had what was known as ‘bovine’ tuberculosis by that time, probably contracted when he was about two years old from milk. It is a virulent form of tuberculosis, which attacks the glands as well as the lungs and causes weight loss and night sweats. As a disease it was cloaked in ignorance and myth and even the experts underestimated it as a fatal disease. ‘Bovine’ tuberculosis, transmitted from humans to cows and back to humans is now dealt with by pasteurisation of milk. Joe Plunkett’s temperament was active, interested, humorous and lively but he had to suffer the restriction and frustration of being frequently confined to bed with this illness all through his life. In 1895 another long family holiday, this time to Brittany for three months, was undertaken with the Count and Countess, her mother, Maria Cranny, five children, Mimi, Joe, Moya, Gerry and one-year-old George, and Gerry’s nurse, Biddy Lynch.

By the time he was seven Joe was being taught by a governess along with his sisters, Mimi and Moya. The Countess often sat in on these sessions and not only interfered, but even competed with the children. In the time-honoured manner, governesses came and went at frequent intervals, but it is to her nurse, Biddy, that Gerry gives the credit for teaching her to read and write. It is likely that this also applied to Joe, although it was usual to take boys’ education more seriously and he would have been the focus of attention from both the Countess and whichever governess was there at the time. The Count left the employment of staff and organising children’s lessons to his wife, but he talked to his children as he would to any adult and about the same things – art, history, French, Italian, books, Irish history – and with the same enthusiasm and affection, so they were simultaneously acquiring another type of education.

In the winter of 1896 Mimi was sent as a boarder to Mount Anville School, and Moya and Gerry to the Sacred Heart Convent, Leeson Street while living with their grandmother, Maria, in 17 Marlborough Road in Donnybrook. After her husband’s death she had moved there from Muckross Park, which her husband built for her. The Countess often sent her children off to other houses and schools and this time she had good reason as she had a small baby, Fiona, at home and was pregnant again.

There was a children’s fancy dress party that year given by the Lord Mayor of Dublin, Richard McCoy, and the Countess decided to send her four eldest children, Mimi, Joe, Moya and Gerry. On the day of the party they were taken to a costume hire firm and dressed up, Mimi in an ‘Irish’ costume, Moya in a Kate Greenaway dress and bonnet, Joe as a Gallowglas and Gerry (who really hated the whole proceedings) as the Duchess of Savoy. Gerry found it stilted and not at all about the children, but there is no record of how the others felt. However the ordeal was not over because they were ‘stuffed’ into the costumes again the next day and taken to the Lafayette studios on Westmoreland Street to be photographed both as a group and individually. The result is beautiful and dramatic, but taking photographs at that time was a slow process requiring the subject not to move for a long time, always difficult for children, so they used to put their head and neck in a brace to keep them still. In the end the expense was enormous and the pleasure only for the adults.

In 1897 the family rented a house called Charleville in Templeogue on the outskirts of Dublin and the children were sent there with Biddy Lynch. What was supposed to be a few months turned into a year with visits from their father and, occasionally, their mother. This meant that Mimi, Joe, Moya and Gerry were now missing school, but they did have a governess, Mademoiselle Ditter, whom Gerry describes as:

… small and dark, a wild creature and a terrible tyrant, and she always abandoned us if possible. She was supposedly French but in fact she came from Alsace and had a strong hatred of the French. She used to teach us how to curse the French with appropriate gestures and to sing anti-French songs. She did also teach us to recite real French poetry and sing more conventional songs and to sew and make paper flowers.

Countess Plunkett liked only French to be spoken at the dinner table and the children did learn enough of the language to read French books of all kinds for pleasure. Food was supposed to be sent to Charleville from town on a regular basis, but their mother frequently forgot. Six children, a couple of servants and a wild governess in a country house with no access to money or shops needed to be resourceful. When they ran out of food there were hens but the hen-house was kept locked and the Countess kept the key with her in town so Moya was delegated to break in to it and take the eggs, which she did by squeezing through the hens’ door. It was in Charleville also that they got Black Bess, a well-trained, good-mannered four-year-old pony. The older children could ride her and drive her in the trap, enabling them to explore the countryside with great freedom.

Jack Plunkett, the youngest of the seven children, was born that October and shortly afterwards the rest of them were brought back to Fitzwilliam Street.

Count Plunkett’s title was bestowed on him by the Pope in recognition of his gift to an order of nuns, The Little Company of Mary (known as The Blue Nuns), of a villa in Rome so that the order could have a house there. He was a nationalist in the Parnellite tradition, having been a friend of both Isaac Butt and Charles Stewart Parnell himself. He stood for election as a Parnellite in constituencies where he was unlikely to win because he could afford to lose his deposit, but could test support and divide the opposition vote. He also undertook, at his own expense, to reform and update the St Stephen’s Green electoral register, which covered a large area of Dublin. Count Plunkett bought a typewriter (only invented twenty years before) for his work on the register and when it was finished brought it home where, to their great delight, the children had the use of it. When Parnell was leaving Dublin in 1891 for what turned out to be the last time he called unexpectedly to see the Count in Fitzwilliam Street and waited a couple of hours for him but, sadly, the Count didn’t get back in time; Parnell died only a few months later in Brighton. In 1898 Count Plunkett, who stood for election again that year in the Stephen’s Green area and nearly got in, was going round the house singing Who fears to speak of ‘98 to celebrate the centenary of the 1798 Rebellion:

Then here’s their memory, let it be

To us a guiding light

To cheer our fight for liberty

And teach us to unite!

John Kells Ingram (1823-1907)

Biddy Lynch, who had a great collection of songs, was joining in and adding appropriate songs of her own. As there was hardly any teaching of Irish history in schools or out of them, songs were an important source of information for the many in the populace who were hungry for it. Count Plunkett was rejected as a candidate for the Irish Parliamentary Party by John Redmond in 1900 for being too radical in his nationalism. In 1895 he had said ‘Do we vote for the country that crushes us, or for the beginning of our liberty?’ – too radical for Redmond.

There were also visible and audible contradictions between the way the Plunketts lived and what they saw around them. The majority of those living on Fitzwilliam Square and Street would have been strongly unionist, that is to say, wishing for the uninterrupted continuation of the union between Britain and Ireland, particularly as it would be the best way to continue their wealth, business and professions, but behind the Square and the Street were lanes full of great poverty and squalor, families living in and over stables with no facilities, regular chaos and violence, which could all be heard from the houses in front. All this had a considerable effect on ten-year-old Joe who from December, 1898, was in school in CUS (Catholic University Schools) Leeson Street, while the girls were back in the Sacred Heart Convent school just across the road. The Countess usually failed or forgot to arrange for her children to have such things as uniforms, copybooks or pens. At this time she was away on a trip so they stayed in various places including their grandmother’s in Donnybrook, but most days they went to see their father in Fitzwilliam Street where he was preparing his book on the painter, Botticelli. On Saturdays he gave them pocket money: Mimi and Joe got twopence, Moya and Gerry got a penny.

Joe’s time in CUS was very short; four months later in March 1899 he contracted pneumonia and pleurisy. Pneumonia was well documented and the causes known by then but, without proper treatments it was greatly feared and with good reason. It frequently proved fatal for the young, the old and those who, like Joe, had chronic bad health. Its usual symptoms of cough, chest pain, fever and difficulty in breathing were often exacerbated by those of pleurisy, an inflammation of the cavity surrounding the lung which causes stabbing pain in the chest and pain and swelling in the joints; a miserable condition for an eleven-year-old boy. Joe’s mother had no training in nursing but she was good at it and had an interest in it which enabled her, with several staff to help her, to nurse invalids, including her father, through long illnesses. On this occasion Joe was not expected to live and his mother nursed him for months until he started to recover; Joe was always grateful to her for this.

Early in 1900 their grandmother, Maria Cranny, died. Joe was still ill so his brothers and sisters were sent to live in her Donnybrook house with their nurse and nursemaid. They, in their turn, contracted whooping cough and measles and were very ill, Mimi nearly died, and they were sent to a house, Parknasillogue, in Enniskerry, to recover. Joe was also convalescing by then but he was not sent to the country, his mother decided to take him to Rome for the winter to recover as he was still very weak after his long illness. When they got to Paris, she changed her mind and instead put Joe in the Marist school in the Parisian suburb, Passy, as a boarder and she stayed in Paris. Joe acquired good French in the school and became expert in local children’s games but it could not be called convalescing and Passy, with its northern French climate, tended to be cold and wet and bad for his health. By the time they headed home at the end of the year he had developed an enlarged gland in his neck, the first of many.

CHAPTER 2

• • • • •

1902–1906 Country Life

Count Plunkett’s book, Botticelli and his School, was published in August of 1900 and with the £300 he was paid by the publishers, George Bell and Sons, he bought the last seven years of a lease on a house, Kilternan Abbey, in Kilternan, County Dublin, eight miles from the centre of Dublin and very much in the countryside. The Count wanted to give his children country air, finalising the deal while Joe and his mother were still away. For the seven children it was, initially, paradise. Kilternan Abbey was a big house at the top of the Glenamuck Road on one hundred and twenty acres of land, all but five let to local farmers, and with a pillared entrance, there still, on the Enniskerry Road beside the Golden Ball pub. Being sited in the foothills of the Dublin Mountains there were wonderful views of Dublin Bay and far beyond but its design was more suburban than rural. The hall floor included two sitting rooms, one with a billiards table, much used by Joe and Gerry, a conservatory and a dining-room. The Countess and Joe each had a bedroom on the first floor and the top floor had two front rooms, Mimi’s and one shared by Gerry and Moya with the nursery at the back for George, Fiona and Jack and their nurses, Biddy Lynch and Lizzie. There were cellars, yards, outhouses, stables and a bungalow where Count Plunkett lived when he was there. There was also plenty of land for the children to explore, a pond, cows, horses, shrubberies, hillsides, streams, huge glasshouses, and mountains of fruit – figs, plums, greengages, Morello cherries, passion fruit, Muscat vines and thousands of peaches – and they still had their pony, Black Bess.

Gerry writes:

Joe and I went wild whenever we could, roaming all over the hills behind. We would get up at fantastic hours of the morning, usually somewhere around five o’clock, to have the whole world to ourselves. We would find something to eat in the kitchen, and since the doors were always locked and the keys on Ma’s table, we got out a window onto the shed roof or down the fig tree by the kitchen wall. We made a house in one of the evergreen trees in front of the house and we had a whole series of complicated stories for every corner of the place. Out the back, beyond the house, there was a large wild place, which was used for grazing by a local farmer and some way up from it was a wonderful cromlech where we went most days. It was a huge thing with a kind of sacrificial hollow in the top with the word ‘Repeal’ scratched deep into the stone.

Not long after their arrival in Kilternan Joe’s mother sacked the nurse, Biddy Lynch, ‘for impertinence’ and now that she was gone the Countess was in charge of the children, something she was very unused to. She didn’t know them. At this time she had not seen six of her seven children for most of a year and it would have been a year of great change for each of them, given their ages – Mimi was fifteen, Joe fourteen and Moya twelve, Gerry was ten, George seven and Fiona and Jack five and four. The Countess had no idea of the way in which Biddy Lynch had kept the children fed, dressed, organised and happy and she forgot that children grow and need clothes or just ignored it. For whatever reasons, frustration, ignorance, lack of order, she began beating her children. She expected them to be totally obedient to her without telling them what her rules were and when they got things wrong she beat them without explaining why. Each of them reacted differently; Joe always felt a duty to her and he was sufficiently used to her to be able to manipulate her but he could see it was wrong. Mimi used to stand in front of the knife drawer in the sideboard ‘just in case’, Fiona, who was only six, was defiant and Gerry, who already knew she hated her, was terrified. All her life she shook whenever her mother came into the room. The Countess’ violence included thumping them with her closed fists, hitting them with a riding cane or a horsewhip, but when she used this on Joe he fainted and she never did it to him again. She was not unusual for her time; it was regarded by many as normal and even necessary to beat children. ‘Spare the rod and spoil the child’ was a common belief and in Fitzwilliam Street they could regularly hear the judge next door beating his children up and down the stairs. Count Plunkett was rarely there to see these things and he regarded the management of the house and children as his wife’s domain. He had an ambiguous attitude to her, seeing her as both the rightful controller of property and finances (including his own) although she did not have the skills for this. He also left her in charge of the children’s education even though, in that area, he had so much – several good schools including a few years in Nice and studies in Art and Law in Trinity College Dublin – while her only education involved occasionally sitting with her brothers and their tutors and less than a year in a London school.

By contrast, he also saw her as ‘a little girl’, a child who could not be held entirely responsible for her actions. She had a rigid and tyrannical mother and a father who was never there because he was always working. She had access to considerable wealth but didn’t consider herself wealthy – she used to ask her children to pray that she would find four hundred pounds by next Tuesday or ‘they would all be in the workhouse.’ She rarely paid her bills but she kept the management of their many houses to herself and rarely paid the maintenance. She was a very good and enthusiastic traveller and she loved and admired her husband.

From October 1901 Joe was going to Belvedere College in Dublin. From Kilternan he had a return journey there of over sixteen miles each school day. His parents went to the Fitzwilliam Street house nearly every day – by waggonette, train and carriage. Joe wasn’t part of these journeys; he had to leave much earlier to cycle to Carrickmines Station, train to Harcourt Street and from there on his bicycle, to Belvedere and, of course, all this in reverse at the end of the school day. On his return journey the other children met him when they could with the pony and trap as the hill was too steep for cycling. Otherwise he had to walk the nearly two miles. Even for a healthy boy this would have been a debilitating regime, especially in winter and with hours of homework afterwards but for Joe, with a history of illness, particularly affecting his lungs, it was exceptionally difficult. That didn’t stop him pottering around shops on the quays in Dublin and spending his lunch money on bits and pieces, curios, books and pet mice.

From G.N. Reddin:

At school he was inevitably misunderstood. He was not a boy like the rest. His companions classed him with those whom they called ‘queer fellows.’ He puzzled them. They joked at his expense and treated him sometimes with school-boy harshness.

Reddin also says that he was ‘Cold, haughty and independent towards strangers as a boy …’ With so little structured education and such unreliable support from home he felt that he was always fighting a losing battle and Gerry records that he thought he was ignorant and was worried about not having enough education. Gerry, says of all seven of them:

Strangers just thought we weren’t much good. … we were badly dressed, looked peculiar and it seemed as though none of us would ever come to anything.

Not only was Joe already a constant reader but it was at this time that his passion for science and technology took off and, not finding the kind of information he was looking for either at home or in school (subjects there were confined to English, French, German, Maths and Religious Knowledge) he began looking for books, chemistry books in particular, to give him answers. He found some in Webb’s bookshop on the quays. He took over part of a cellar known as Robin Adair’s kitchen in the basement of the Kilternan house as a laboratory and persuaded his mother to buy him some flasks and condensers and basic apparatus. He found it very difficult until he came across J. Emerson Reynold’s Elementary Practical Chemistry. This book made things clear and progressed easily through its subject and Joe and his sister, Gerry, spent hours of fascinated enjoyment trying the experiments. Gerry was later to distinguish herself in Chemistry in University College, Dublin. There were definite limitations on what they could do; there was no gas supply in the house to run a Bunsen burner, which made some experiments difficult or impossible, and when their mother started taking an interest, asking questions and bringing visitors down to the cellar to view her outstanding son’s experiments, Joe was put off. He told Gerry that their mother seriously expected him, at the age of thirteen, to make important and original discoveries and this discouraged him completely. Joe was fascinated by Marconi’s wireless from the start, probably from the time of Marconi’s very first successful transmission from Rathlin Island to Ballycastle in 1898. Joe bought the weekly magazines that published all the information emerging on radio and its development and he had started building his own sets in Fitzwilliam Street and continued in Kilternan.

In 1902 the family all went to meet Miss Evelyn Gleeson, who had just moved to Dundrum, near Kilternan. She was a friend of the socialist artist, William Morris, and had similar aspirations, to make beautiful things accessible to everyone and here she was beginning her lifetime project, the Dun Emer Guild, which was to contribute that beauty to Irish society for more than fifty years. Evelyn Gleeson’s arrival with her sister, Mrs McCormack and the McCormack children of similar age to the Plunkett children, Kitty, Gracie and Eddie, brought great changes in the young Plunketts’ lives. These were friendships that were to last lifetimes. Evelyn Gleeson’s house, Runnymeade, outside Dundrum, was a beautiful big house with a large garden, a very open house, always full of writers, painters, thinkers and talkers. Joe and Gerry joined a brush-painting class given by Lily and Lolly Yeats, sisters of Jack B. Yeats and William Butler Yeats. Nora Fitzpatrick taught them something of bookbinding and the whole house was a centre of talk and artistic creation. They loved it and spent as much time there as they could. All the young Plunketts had some artistic bent, which appeared and developed during their lives, and this time and the people they met fostered their beginnings. Most of the young Plunketts’ socialising was with families known to their parents and their father already knew several families in the Kilternan area when they moved out there. The O’Morchoe family was very close by in the Glebe House, Glencullen, and their father was the Church of Ireland Rector of Kilternan. He and his wife, Anne, had seven children, four boys and three girls, and the three oldest boys, Arthur, Kenneth and Nial, were old enough to become good friends with the older Plunkett children, to roam the countryside and share games of all kinds with them. Being from different religions and traditions they went to different schools and universities and joined different armies, but one of those friendships was to have a strange last crossing in 1916.

Count Plunkett had another friend in the area who was to prove very important to all the young Plunketts and to Joe in particular. Originally from Marseilles and then Paris, William Arthur Rafferty, a Frenchman and an engineer all his life, had run away from his family to the 1861 Great Exhibition in London, which was full of mechanical marvels. From that he realised his dream of becoming an engine driver on the London to Dover train, but he reluctantly gave this up to do what he saw as his duty, taking up his inheritance of a farm, Springfield, at The Scalp just beyond Kilternan. Rafferty got to know Count Plunkett in London and they became firm friends, both were involved in court work in the Kilternan area. He had a daughter, Lena, similar in age to the older Plunkett children and she and her father looked after Joe many times when he stayed with them to recover from his illnesses. They were also kind, in many very personal ways, to the rest of the family, right into their adulthood. Mr Rafferty and Count Plunkett shared a passion for books but in Kilternan the only books in the house available to the children, some of whom were always book-hungry, were those bought by the Count and Countess at Carrickmines Station to read on the train, light novels and detective stories, Sherlock Holmes, and magazines ideal for following developments in radio and photography. Joe and Gerry devoured all of them.

In 1903 Count Plunkett was appointed Secretary to the Cork International Exhibition, a repeat of the very successful1902 Exhibition. He lived in Cork for most of the year before the exhibition, which ran from May to October and included a visit from the English King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra to whom he had to make a presentation. In August of 1903 the young Plunketts produced the first number of their magazine, The Morning Jumper, strictly for their own amusement. Mimi wrote out all their contributions with the youngest two, Fiona and Jack, being helped by the older ones with their stories, limericks and illustrations. The Table of Contents below is from that August edition:

Prologue

The Garden of Sweet Pea

Nonsense Rhymes

The Fiddling Wizard

Nonsense Verse

Charm for Dispelling Beauty

The Bad Robbers

More Nonsense

The Miller’s Dog

The Tulip Fairies

Sonnet

The Magic Emerald

There are no credits or indications as to who wrote what, but in that August edition nine-year-old George Plunkett won the nonsense poetry competition with this:

When I was old and knew so much

I never cared to use or touch

A fiddle – for when I was young

I broke the strings and near was hung.

In the Christmas issue, with Mimi away in Rome, it is clear from the handwriting (this time many hands are discernible) that their mother became very involved (Gerry records that she became excited about the whole thing) and most of this ‘Double Number’ is written by her. There are several typed contributions and plenty of illustrations and this number includes the following:

The Editors and staff of The Morning Jumper tender their best thanks to the kind and sympathetic contributor who sent them the following verses:

Sing a song of sixpence, a booklet full of nous,

Seven clever authors all in one house,

When the book was opened they all began to sing,

Wasn’t that a dainty treat to set before a king?

First is Philomena Editor in chief,

I know that she is saying now Oh aged bard be brief,

Sub editor is Joe, a learned man withal,

Whose scientific skill my weak mind doth appal.

Then comes helpful Moya jingling household keys

And laughing Geraldine as sweet as honey bees,

Make way for George the fifth our king by divine,

A manly little man and a special friend of mine.

Next with little frills upon her little frocks,

Fairy Fiona dances in as gently as a mouse

And last is Master Jack who though shorn of his locks

Still manages to shake the pillars of the house.

X L.C.R. (Lena C. Rafferty, daughter of Mr Rafferty of Springfield)

Mimi and Moya were now boarding in Mount Anville School, but Joe’s attendance in Belvedere became very erratic and then fell away altogether as bad health took over again. He had attended the school for only two years. Now aged fourteen it was decided that the swollen glands in his neck would have to be lanced, cut open to alleviate the blockage and this was done at home in Kilternan by his uncle, Dr John Joseph (Jack) Cranny, who had a private practice and was attached to several Dublin hospitals. Nurse Keating was brought out to Kilternan to nurse Joe through his recovery and the Countess left for one of her many long holidays, this time on a cruise to Lisbon with her daughter, Moya, as chaperone, leaving twelve-year-old Gerry in charge of the household, shopping, catering management, servants – everything! The Countess saw nothing strange in this arrangement and Gerry did have some inexpert help from her father whom she loved dearly.

The earliest pieces of writing by Joe Plunkett to have survived are fragments of stories written in April and May 1904. It is very likely he was ill again – one of the pages has the score from a game of Bezique with his mother (she won) and it is also likely that The Morning Jumper had sparked off ideas. These fragments look like drafts or just doodling for stories, a novel, a fairy story, a thriller or a detective story … The punctuation (never Joe Plunkett’s forte) is his own.

Saturday 9th April 1904

Confessions of a Murderer

Though still a young man I have committed more murders than any man living or executed by law. In fact there is or rather was only one who came anywhere near me in this matter of killing and he poor fellow (strange that I should feel pity for anyone) – an ignominious death in the electric chair.

10 April 1904

Shady and the Fairy Bullfrog

By MJ Work

Once upon a time there was a little ghost who lived all alone with his mother in a family vault. He was six and a half years old and his name was Shady. One day he went to his mother and said ‘Please Mummy will you give me a penny to buy a bullfrog?’ ‘What for?’ said his mother ‘Oh just to play with’ answered Shady.

So his mother gave him a penny and he went away to buy a bullfrog. When he came to the shop he saw several bullfrogs in the window so he went in and said ‘How much are your bullfrogs if you please?’ and the shopman said ‘A pennyfarthing’. The shopman said then seeing the disappointment of the little ghost ‘If you promise to be good I will give you this little one for a penny’ ‘Thank you very much’ said Shady as he paid his penny and took the bullfrog. What was his surprise when on looking closer at his bullfrog in the open air to see a tiny golden locket hanging around its neck. Shady immediately tried to open it when he was startled by a voice saying ‘Leave that alone’. Shady looked around but saw nothing. He then tried again to open it and the voice said again, this time more loudly, ‘Leave that alone’. ‘Shan’t’ said the little ghost and redoubled his efforts to open the locket.

He had just succeeded in forcing it open and catching a glimpse of HIS OWN FACE!! in it when suddenly he saw the bullfrog become transformed. The locket slipped from his hands and he found himself confronting A FAIRY!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Saturday 21st May 1904

‘Father are you very busy, I have something to tell you’ said a tall dark and very pretty girl of nineteen coming into the laboratory of Mr Lexonbridge the celebrated chemist when he was engaged in research on radium.

Joe’s glands were now very swollen again and an operation was performed on them by Dr Swan, a friend of Dr Cranny.

In Gerry’s account of it she says:

He hacked poor Joe about savagely, referred to the healing tissue on Joe’s neck as ‘proud flesh’, and burned it off with copper-sulphate crystals without an anesthetic.

The carotid artery was now just under the skin and from then on it was impossible for Joe to wear a properly fitting collar as it strangled him. The operation was performed in the Orthopaedic Hospital, 22 Merrion Street and Joe was afterwards sent to convalesce in Delaford, on the Firhouse Road, owned by Dr Swan. The whole experience was shocking and traumatic for Joe and his recovery from it took a long time.