Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

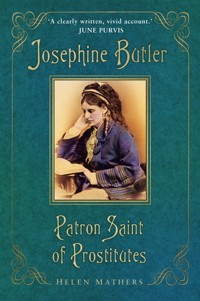

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The 'steel rape' of women is a scandal that is almost forgotten today. In Victorian England, police forces were granted powers to force any woman they suspected of being a 'common prostitute' to undergo compulsory and invasive medical examinations, while women who refused to submit willingly could be arrested and incarcerated. This scandal was exposed by Josephine Butler, an Evangelical campaigner who did not rest until she had ended the violation and helped repeal the Act that governed it. She went on to campaign against child prostitution, the trafficking of girls from Britain to Europe, and government-sponsored brothels in India. In addition, Josephine was instrumental in raising the age of consent from 13 to 16. Josephine Butler is the poignant tale of a nineteenth-century woman who challenged taboos and conventions in order to campaign for the rights of her gender. Her story is compelling – and unforgettable.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 683

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Nigel, who has supported this project throughout

Contents

Title

Dedication

Maps

Family Trees

Introduction

Prologue Josephine Butler in Pontefract

1 A Beautiful Home in an Ugly World

2 Josephine Meets George

3 Married Life in Oxford

INTERLUDEA Victorian Obsession: Rescuing Prostitutes

4 Births, Illness and the Move to Cheltenham

INTERLUDEVictorian Prostitutes by Day and Night

5 The Butlers in Liverpool

INTERLUDEThe Dark Side of English Life

6 The Birth of a Feminist Campaigner

INTERLUDEA Victorian Brand of Feminism

7 Education and Employment for Women

INTERLUDEDr Acton and the Lock Hospitals

8 ‘This Revolt of the Women’

INTERLUDESteel Rape

9 The Constitution Violated, 1870

INTERLUDESpeaking on Public Platforms about Unmentionable Subjects

10 The Royal Commission, Bruce’s Bill and the Pontefract Election (1871–74)

INTERLUDEThe Attack on Women’s Bodies

11 The New Abolitionists (1874–75)

INTERLUDEThe Hour Before the Dawn

12 The European Slave Trade (1875–80)

INTERLUDECatharine of Siena

13 Success for the Repeal Campaign (1881–83)

INTERLUDEThe Salvation Army in Switzerland

14 ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’, 1885

INTERLUDEEllice Hopkins, Purity and Vigilance

15 Time for George (1886–90)

INTERLUDEThe Queen’s Daughters in India

16 Struggle and Bereavement (1890–98)

INTERLUDEThe Boer War

17 The Storm-Bell

Epilogue

Appendix 1 Josephine Butler’s Siblings

Appendix 2 Josephine Butler’s Homes: An Update

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Plates

Copyright

THE GREY FAMILY

THE BUTLER FAMILY

Introduction

I first heard about Josephine Butler when I was an undergraduate history student, and I began to research her writings in 1998 when I was a university teacher of religious and women’s history. I was astonished by the power of her conviction and her personality, the range of her ambition and the extent of her achievements. I wanted to understand her, and I found that task to be long and complex – so long, indeed, that I put it aside several times in order to complete other books. Since I started my research, other books about Josephine Butler have been published, and yet it remains true that her name is not well known to the British public – but it should be. She was once described as ‘the most distinguished Englishwoman of the nineteenth century’.1 She was the leader of a national women’s political campaign in Victorian England, at a time when women did not have the vote, and succeeded in repealing a law to which she and her followers strongly objected but which public opinion generally supported.

Josephine Butler’s life spans the Victorian age – born in 1828, she was 9 when Victoria came to the throne, and died five years after the Queen, in 1906. She was tall and beautiful, with thick lustrous hair which she wore long, in ringlets tied with ribbon or secured with a plait. She was slim, and always dressed with care, choosing tactile fabrics like lace and damask, set off by dramatic beads and earrings. She played the piano with true skill and sensitivity, and loved animals, especially dogs and horses. She came from a comfortable family home in the countryside, and was a devoted daughter and sister.

She was happily married to a husband who adored her and they had four children. But at the age of 40, Josephine became obsessed with the needs of women who were completely unlike herself. While living in Liverpool, she began to care for imprisoned and ill prostitutes, even inviting some to live in her own home. After the Contagious Diseases Acts were passed, which allowed these women to be sexually assaulted by police surgeons on a regular basis, she went into battle with Parliament, the police and the judges to change the law.

This battle consumed her home life, and undermined her physical and emotional health. Many times she collapsed and was confined to bed for weeks, but she kept the campaign going and secured the change in the law. The Ladies’ National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, which she led, was the first national women’s organisation to score such a triumph in England. After this triumph she did not retire, but until the end of her life carried on trying to help abused women.

Why is Josephine Butler not as famous as Victorian heroines like Florence Nightingale? She achieved as much as Nightingale, probably more. But she was never celebrated by her country, never became a national heroine. Indeed, to many she was the reverse of a heroine, because she fought for women’s rights, at a time when (with the single exception of Queen Victoria) men had all the power. Even worse, she fought for ‘fallen’ women, who were regarded as ‘subhuman’ by polite society. Prostitutes, she was told, were ‘a class of sinners whom she had better have left to themselves’ since they were the authors of their own destruction.2 Josephine Butler never gave up, never backed down and forced society to face the sordid details of the abuse she was fighting. No wonder she was unpopular. Some of that rejection, that unpopularity, seems to have clung to her memory ever since.

This book aims to explain Josephine Butler’s complex personality, motivated as she was by both feminism and her deep Evangelical Christian faith. The best way to understand this is through an account of her life and her relationships with her family, her supporters and her God. As a professional historian, I have sought to contextualise her campaigns with ‘Interludes’ between the chapters explaining the historical background. Other Interludes explore her most important writings.

Josephine Butler’s dramatic life story is far more sexually graphic than any Victorian novel. She went into brothels, prisons and the ‘lock’ hospitals where women were examined and treated against their will. She stood up to cruel and coldly calculating authority figures such as the Superintendent of the Morals Police in Paris, the Minister of Justice in Rome and the Public Prosecutor in Brussels. It is also a great love story – the marriage of Josephine and George Butler was blissfully happy and an invaluable source of support to her.

‘She chose a life which was a crucifixion’ is the verdict of one contemporary.3 Yet her achievements had lasting impact. Her name deserves to be remembered by all who value women’s struggles to improve their lives.

PROLOGUE

Josephine Butler in Pontefract

The following story, in her own words, illustrates Josephine Butler’s character. In 1872 she and her friends were trying to stop the election of a candidate they detested, a man who supported the ill-treatment of prostitutes and had pimps among his supporters. The scene of this tense by-election was Pontefract in West Yorkshire, where large crowds had gathered and passions had been roused on both sides by fervent speeches. The fact that women were among the campaigners enraged men who thought they had no business becoming involved. The welfare of prostitutes was, in any case, a topic which respectable women should never speak about.

Josephine was undaunted by this, and indeed determined to find as many public platforms as possible. She decided to stage a parallel meeting to that of the candidate she opposed, Mr Childers:

On a certain afternoon, when Mr Childers was again to address a large meeting from the window of a house, I and my lady friends determined to hold a meeting at the same hour, thinking we should be unmolested. We had to go all over the town before we found someone bold enough to let us a place to meet in. At last we found a kind of large hayloft over an empty room on the outskirts of the town. You could only ascend to it by means of a kind of ladder, leading through a trapdoor in the floor. However, the place was large enough to hold a good meeting, and was soon filled.

… the women were listening to our words with increasing determination never to forsake the good cause, when a smell of burning was perceived, smoke began to curl up through the floor, and a threatening noise was heard below at the door. The bundles of straw beneath had been set on fire …

Then, to our horror, looking down the room to the trap-door entrance, we saw appearing head after head of men with countenances full of fury; man after man came in, until they crowded the place. There was no possible exit for us, the windows being too high above the ground, and we women were gathered into one end of the room like a flock of sheep surrounded by wolves …1

Since the women were trapped, all they could do was stand firm in the face of the shouting, swearing thugs who were advancing on them. Some were obviously pimps. Josephine and her friend Charlotte Wilson were their targets:

… Mrs Wilson and I stood in front of the company of women, side by side. She whispered in my ear, ‘Now is the time to trust in God; do not let us fear’; and a comforting sense of the Divine presence came to us both. It was not personal violence that we feared, as what would have been to any of us worse than death; for the indecencies of the men, their gesture and threats, were what I would prefer not to describe. Their language was hideous. They shook their fists in our faces, with volleys of oaths. This continued for some time, and we had no defence or means of escape.2

Their male supporters arrived but were unable to help, and indeed made matters worse:

… A fierce argument ensued. Meanwhile stones were thrown into the window, and broken glass flew across the room … Our case seemed now to become desperate. Mrs Wilson and I whispered to each other in the midst of the din, ‘Let us ask God to help us, and then make a rush for the entrance.’ Two or three working women placed themselves in front of us, and we pushed our way, I scarcely know how, to the stairs. It was only myself and one or two other ladies that the men really cared to insult and terrify, so if we could get away we felt sure the rest would be safe. I made a dash forward, and took one leap from the trap-door to the ground-floor below. Being light, I came down safely. I found Mrs Wilson with me very soon in the street.

Once in the open street, these cowards did not dare to offer us violence. We went straight to our own hotel, and there we had a magnificent women’s meeting. Such a revulsion of feeling came over the inhabitants of Pontefract when they heard of this disgraceful scene that they flocked to hear us, many of the women weeping. We were advised to turn the lights low, and close the windows, on account of the mob; but the hotel was literally crowded with women, and we scarcely needed to speak; events had spoken for us, and all honest hearts were won.

In pursuit of her campaign, Josephine was brave, determined, even foolhardy – in order to hold her women’s meeting she risked violent attack, even rape (‘what would have been to any of us worse than death’). Although she felt at that moment that she ‘had stirred up the very depths of hell’, she carried on.3

1

A Beautiful Home in an Ugly World

‘The bright large family circle’

Josephine Butler was born on 13 April 1828, the seventh child of John Grey and his wife Hannah Annett. The Greys were country people, born and bred in the north-eastern borders, where the Cheviot Hills divide England from Scotland. The Northumberland border country of Glendale, along Hadrian’s Wall, is remote and thinly-populated – Josephine described it as ‘bleak and almost savage’ in character.1 Its people were tough, determined, combative and self-reliant, shaped by the clashes which scarred centuries of border history. John Grey’s home was only a mile from the site of the tragic Battle of Flodden in which ‘the flowers of the forest’, the noble youth of Scotland, ‘were a’ wede away’.2 Josephine remembered her father reciting these lines as she walked with him there; she loved ‘border tales of tragedy and romance’ and shared his love for ‘sweet Glendale’.3 Her Grey ancestors had lived there for centuries ‘derived from a long line of warriors, who were Wardens of the East Marches’ and governors of the border castles.4

By the time of Josephine’s birth the Grey family had three branches with local estates. One distant cousin, Charles Earl Grey, whose estates were at Howick, has several claims to fame. As the Whig Prime Minister 1830–34, his administration passed the first Parliamentary Reform Bill (1832) and abolished slavery in the British Empire (1833).5 In his youth he was the lover of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire whose husband the Duke forced her to give up the daughter, Eliza, fathered by Grey.6

Josephine’s branch of the family had no such skeletons in the closet and its property was relatively small, consisting of farmland and a house, Milfield Hill, overlooking the River Tweed. Her grandfather, George Grey (1754–88), had cleared the land from wild forest and started farming, but he died tragically young leaving his wife Mary with four young children. She rose to this challenge magnificently, and succeeded in managing the farm and raising her children single-handedly. Josephine’s grandmother was a ‘very thoughtful and studious’ woman, who educated her children while doing the household chores.7 They were encouraged, for example, to learn epic poetry, such as Scott’s Marmion, by heart and she borrowed books for them from the local lending library. Later she found the money to send both her boys and girls away to school. Mary Grey was herself a model of female independence and resilience, and an influence on Josephine’s views about what women could achieve, even though she died before Josephine was born.

John Grey was 8 when his father died. Ten years later, as the eldest son, he took over the management of his ‘patrimonial estate’,8 along with land which the family farmed as tenants. By all accounts he was an excellent farmer and land manager, an enthusiast for the agricultural reform which was transforming the countryside. Waste land was reclaimed and fenced off, turnips were grown to dramatically enhance the yield from crop rotation, and threshing machines efficiently processed the grain harvest. The animal stock was improved beyond recognition through selective breeding and better nutrition. John Grey also had a talent for making good relationships with both staff and tenants, and was highly respected among his neighbours.

Josephine’s mother, Hannah Annett, came from nearby Alnwick; her ancestors were ‘poor but honest’ Protestant silk-weavers driven out of France, probably in 1685.9 It was unusual for ‘Huguenot’ families in England to move so far north, however – the vast majority went to settlements in London and the south.10 Hannah Annett met John Grey at a country inn where both had stopped for food and shelter during a long ride through snow. Her mother romantically recalled for Josephine the moment that John ‘placed himself in front of her horse, held its rein with a firm hand, and, fixing his eyes on her, said some words …’ Her mother did not repeat the words, but they ‘sent her on her way in such a frame of mind that her horse sometimes took the wrong turn in the road without her noticing it’.11 They were married within the year, ‘the bride riding to church dressed in a beautiful pale blue riding habit, richly embroidered’.12

John and Hannah took possession of Milfield Hill on their marriage. Mary Grey moved out, John’s sisters were already married and, although his brother George stayed on, he too departed a few years later for London. There George died in sad and painful circumstances after a fall ‘from a horse or carriage’ – the details were never clear to the family because they were not contacted until several weeks later, when he was at death’s door. A devastating postscript to a letter summoning John told him, ‘His struggles have ceased exactly an hour.’ Too late, John travelled to London by mail coach to be told the story of George’s last days, and the many times he had called out for his brother and mother.13

John and Hannah had ten children in total; three boys and seven girls, of whom Josephine was the fourth girl. Her brother George, the eldest child, was 13 when she was born, followed by John (11), Eliza (9), Mary Ann (‘Tully’, 7), Fanny (5) and Charley (3). George and John were old enough to seem distant to a little girl, but Josephine was always close to her sisters and to Charley. The family were fortunate that their mother was so strong – at a time of high maternal mortality Hannah survived all her births and enjoyed good health for most of her life. The Greys celebrated their 45th wedding anniversary before Hannah died in 1860.

Dilston House

Both Hannah and John loved their Milfield home, but in 1833 John was offered an opportunity he could not refuse – the management of the vast estates belonging to Greenwich Hospital, totalling over 34,000 acres, which were scattered all over Northumberland. He was ideally suited to this new role, which gave him wider scope for agricultural reform and for educating the farmers. His conscientious work proved to be a ‘model of estate management’.14 Josephine adored her father and was proud that he was described as ‘a good and wise and powerful man’.15 Travelling around the county, overseeing work on the land and introducing improvements to the agriculture and the conditions of the tenants meant inevitably that much of his time was spent away from home.

By this time Hannah had nine children at home in Milfield, after the births of Harriet (‘Hatty’) and Ellen (‘Ellie’). John missed them all deeply, and wrote to Hannah asking for news of them, especially the youngest, who was only 1 – ‘How I should like to see little Ellie toddling on her own small feet’.

Shortly afterwards, the three younger children caught scarlet fever; Ellie then succumbed to typhus and died while John was away from home.16 Like John, Hannah doted on their small children, describing her grief in a letter to him written several months later, ‘… in walking the street, if my eye rests on a little one with tottering feet and chubby hands, my heart sinks within me. Oh! How many darts pierce a bereaved mother’s bosom which no one knows of!’17 This tragedy cast a cloud over their plans to move to a new house.

John and Hannah were offered the chance to build a home on his employer’s land, and selected a hilltop site at Dilston, dramatically positioned high above a river called the Devil’s Water. This beautiful and secluded location even had the romantic ruins of a fifteenth-century castle in its grounds.18 They designed a spacious family home – large enough for each child to have a bedroom, with plenty of room for visitors as well. They moved there in 1835 when Hannah was still mourning the loss of Ellie. Her eldest son, George, had also stayed behind to take over the management of Milfield, 60 miles distant over narrow lanes. For her there was ‘a pleasure in the pathless woods’ but sadness that ‘our little group’ was not complete, and never would be again.19

For Josephine (‘Josey’), now 7, and her brothers and sisters, Dilston was perfect. This is Josephine’s evocative description:

Our home at Dilston was a very beautiful one. Its romantic historical associations, the wild informal beauty all round its doors, the bright large family circle, and the kind and hospitable character of its master and mistress, made it an attractive place to many friends and guests … It was a place where one could glide out of a lower window, and be hidden in a moment, plunging straight among wild wood paths, and beds of ferns, or find one’s self quickly in some cool concealment, beneath slender birch trees, or by the dry bed of a mountain stream.20

Clearly Josephine sometimes liked to escape from the company of so many brothers and sisters!

She was a studious and thoughtful child, reserved and ‘shy’, with delicate health after a premature birth – she described herself as ‘a weak, wretched infant, hard to rear at all’.21 If Josephine was difficult to rear, this might explain why she appears to have been closer to her father than to her hard-pressed mother. During games with her siblings she often felt faint if she ran around a lot. This did not stop her enjoying outdoor life, but she spent a lot of time in sedentary pursuits like reading, painting and playing the piano. As a pianist she had genuine talent, and Hannah encouraged her to practise seriously and to become a good musician, rather than simply a competent parlour performer.22 Josephine took great pleasure in playing well and, as a teenager, was given a ‘splendid grand piano’ by her father which the family loved to hear her play. Her sister Hatty remembered in particular ‘the magic of the Moonlight Sonata’ – one of Beethoven’s sonatas in a bound volume which Hannah gave to Josephine and which she treasured for the rest of her life.23

The Siblings

Hatty was two years younger than Josey and within the family they formed a pair. Closest together in age, they ‘walked, rode, played and learned our lessons together’.24 Hatty was robust, chubby, gregarious and cheerful, the perfect foil for Josey’s introspection and occasional low spirits. Throughout her life Josephine relied on Hatty’s good sense and unquestioning devotion. They both loved animals and had pets, including not only dogs but also ‘ferrets, wild cats from the woods and owls’.25 Hatty collected so many newts in jam jars on a shelf above her bed that it collapsed, flooding the mattress.

In the stables were ponies which all the Grey children learned to ride. Josey became a proficient and enthusiastic rider, but Hatty was the one who managed to stand upright on the saddle and wanted to run away to join the circus.26 They trained horses for their father, and as teenagers enjoyed going hunting at Milfield with their brother George. Often they accompanied their father on his rides round the estate, as Hatty recalled:

… sometimes such merry wild gallops over high grass-fields in Hexhamshire, or above Aydon, bending our heads nearly to the horse’s mane, to receive the sharp pelting hail on our hats, the horses laying back their ears, and bounding at the stinging of the hail on their flanks, and coming in with heavy clinging skirt, and veil frozen into a mask the shape of one’s nose, revealing very rosy cheeks when it was peeled off …27

This evocative description shows that Josephine was not the only inspired writer that the Grey family produced. Josey recalled Hatty’s heartbreak when her pet dog, Pincher, was accused by local farmers (unfairly in her opinion) of worrying sheep. He ‘was tried, condemned and executed … wagging his tail to the last and offering his paw, in sign, my sister said through her tears, of forgiveness of his murderers’.28

Hannah gave birth to her last child, Emily, at the age of 42 in 1836. As the six daughters grew older, each was allocated a bedroom leading off the upstairs hall. Sometimes they would be summoned by a shout from their father’s dressing room, because ‘the tying of a necktie was a mystery he never could compass … It always ended with the appearance of a piece of crumpled hemp’. All the available daughters would rush out of their rooms, ‘anxious to help the old Dad’ but some had to stand on a stool as he was so tall.29

This family scene was described by Josephine – others come from her parents’ letters. On New Year’s Day 1843, John wrote to Tully, ‘some of the young folks are reading, and others chatting in the blaze of a Christmas fire in the drawing room. I hear Charley’s voice overheard in discourse with mamma. He looks the little man in tails less gracefully than the tall boy in a jacket.’30 Evidently Charley had been forced to adopt a man’s tailcoat at the age of 17. As the youngest of the three sons, Charley seems to have been quite the favourite of his mother – once when absent from home to stay with her uncle Hannah wrote to John of how much she missed the family, ‘It would be quite a treat to see Charley come in and throw his hat in a wrong place, and leave his books in a litter, as that would give life to the scene.’31

By this time John, the second son who had a punctured lung caused by an accident, had left home to visit his sister Eliza in Hong Kong in the hope of improving his health.32 Josephine quotes touching letters to him on his voyage from their father: ‘My very dear John, I am often thinking of you when the wind raves among our trees. But then I recollect that it may be calm in your hemisphere … Be watchful, my dear boy, of your thoughts and actions, make good use of your opportunities of observation, take especial care of your health, and come back cheerful and strong and instructive. Ever your affectionate father, John Grey.’33 The letter never reached John as he had ‘died off the Cape’, as the family discovered in a terse message from his boat while berthed in China. Months later they received a ‘badly spelled and badly written’ letter from a sailor-boy who had looked after John and reported that, on his deathbed, ‘Mr Grey sang out for his mother … [and] talked much about his brother George and thought he was coming to him’. Hannah took hope and comfort from this letter, happy that her son had had a friend to cheer him and to read him ‘the word of life’, the Bible.34

‘It was my lot from my earliest years to be haunted.’

The Grey family was happy and idyllically cocooned in the countryside, but John and Hannah did not forget the outside world. John, in particular, more pessimistic and introspective than his practical and positive wife, could become obsessed with the horrors endured by less fortunate people. Josephine’s father was a committed supporter of anti-slavery campaigns. He was horrified by ‘a system in my mind repugnant to every principle of justice and to every feeling of humanity’.35 John was 21 when William Wilberforce’s campaign against the slave trade came to its triumphant conclusion in 1807; the battle moved on to the freedom of slaves in the British colonies. John spoke against slavery at election meetings, organised petitions and made the acquaintance of leaders of the movement. He was in close touch with his cousin, the Prime Minister, and rejoiced that he was able to lead this campaign to success in 1833. John went on to join the campaign to free the slaves on the plantations of the American South. Josephine remembered a visit to their home by one of its leaders, William Lloyd Garrison – a sign of how important her father’s influence was. Garrison became one of her heroes; in her own campaigns she often used his catchphrase – ‘I will be as harsh as truth and as uncompromising as justice. I am in earnest … and I will be heard.’36

Like most anti-slavery campaigners, John Grey was inspired by religious conviction. He was an Evangelical, like Wilberforce, and believed that, as a born-again Christian, he should attack evil in the world wherever he found it. Slavery was an evil, a denial of the fact that God loved all men and women, of whatever colour, equally. Evangelical families like the Greys were on a mission against sin, and their children were caught up in it.

When John Grey became a father, he introduced his children to the family’s mission and did not spare them the shocking details. So Josephine learned at a young age of whippings and brandings, and the separation of slave children from their parents. Her father told her of slave sales in which the ‘merchandise’ was poked, prodded and assessed like cuts of meat. The strongest impact on Josephine was made, she said, by the dreadful treatment of female slaves, who were ‘almost invariably forced to minister to the worst passions of their masters’.37 One story she never forgot was that of a slave woman:

… who had four sons, the sons of her master. The three eldest were sold by the father in childhood for good prices, and the mother never knew their fate. She had one left, her youngest, her treasure. Her master, in a fit of passion, one day shot this boy dead.38

The mother did not survive this final blow, but died distraught and despairing. Recalling these stories later, Josephine wrote that they ‘awakened my feelings concerning injustice to women through this conspiracy of greed and gold and lust of the flesh’.39 Her strongest feelings were for suffering women; she felt that they endured more because of their sex and had much less power to do anything to improve their situation.

Stories of slavery and suffering conjured up images which, she said, ‘haunted’ her.40 When she was 17, this caused a crisis of doubt about the Christian faith she had learned and accepted as a child, questioning why God allowed this suffering and why the world seemed ‘out of joint’.41 She described it as ‘one long year of darkness’.42 She ran out into the woods and ‘used to shriek to God to come and deliver’. Her sisters, not surprisingly, thought she was ‘a little mad’.43

Josephine eventually found a measure of peace and acceptance, but her questions remained for many more years before she found the answers she was looking for. She also became seriously ill around this time when she ‘broke a blood vessel in my lungs.’44 Her family feared for her life, especially after a visit from her brother-in-law, the husband of her eldest sister Eliza, who was a surgeon. He pronounced her ‘doomed’.45 She recovered from this and similar attacks in the future. Her resilience in the face of serious health problems, which kept her in bed for weeks at a time, is one of the recurring themes of Josephine’s life.

Until she was 19, Josephine’s travels hardly extended beyond a 60-mile radius of her home. Although she was well informed about its existence, she had very little direct experience of poverty. A trip to Ireland in 1847 brought her a terrible enlightenment. In the Irish potato famine of the mid-1840s, hundreds of thousands of Irish peasants had starved to death. Many more had fled abroad, to England or America, to escape the terrible hunger and the barren land filled with rotting, useless plants. Those who were left behind were often the weakest and most desperate. When Josey and Hatty visited their brother Charles, who was staying in Ireland, the horror of what they saw was overwhelming. Josephine recalled that the gardens and fields in front of the house were:

… completely darkened with a population of men, women and children, squatting, in rags; uncovered skeleton limbs protruding everywhere from their wretched clothing, and clamorous, though faint voices uplifted for food.46

There was a ‘strange morbid famine smell in the air’. This terrible experience was her first encounter with abject suffering. Josephine wondered once more why evil and pain were such dominant features of a world created by God.

Faith and Happiness

These unhappy experiences were powerful enough for Josephine to recall them in old age, but most of her teenage life was happy, relaxed and convivial. The Grey children enjoyed a lively social life with plenty of dressing up and dancing. They went to all the local balls where, Josephine recalled, she and her sisters ‘were great belles, in our snowy book-muslin frocks, and natural flowers wreathed in our heads and waists and skirts’.47 Emily, the youngest, accompanied them at the age of 15, ‘her golden hair dressed like a crown’.48

The Alnwick County Ball attracted all the local gentry, and John was joined by his cousin Lord Grey, Lord Howick and Lord Durham ‘all standing in a group in the very middle of the ballroom floor, regardless of the dancers all around them, deep in some Liberal political intrigue’. Josephine danced with the heir to Lord Tankerville, even though ‘my father did not quite like my dancing with a Tory!’49

The Greys owned a family carriage, drawn by two horses, which they used for great occasions, like the trip to the County Ball. They also kept two carriages which seated four people and a ‘high small open gig’ in which John Grey often drove Josey and Hatty.50 They usually made the journey to Milfield in an open carriage, with a one night stop. In 1839 the first railway from Newcastle to Carlisle opened, passing so close to Dilston that a private station was built. This gave easy access to Dilston for their wide circle of friends and relatives.

At Dilston the Greys entertained guests on an impressive scale. Hatty noted ‘such a house full’ in the summer of 1850 when at least eleven stayed at once.51 Some friends and relatives remained for weeks at a time; Hatty preferred those who ‘fitted … into the family’ and did not demand to be ‘amused’. A favourite was Miss Sands, who ‘thought it so nice to paint and practise with Josey’. There were many excursions to local places of interest, like the ‘jolly little picnic to Stewart Peel and Langley Castle’ when their sister Tully and her husband Edgar were visiting, evocatively recalled by Hatty:

We had the open carriage with Mama and Mrs Morrison, Josey and Tully (with straw hats on) inside, Edgar on the back seat, and Mr Hill beside John on the box … Emmy and I rode on Bobby and Undine … We … had the horses put up an hour at the Peel while we rambled about and gathered wild flowers … the deep ravine [was] close on each side, with such a mass of wooded park to look down upon … After a time we became so hungry we could admire no more, and returned to Langley, which we reached at 5 o’clock and didn’t we set to with hearty goodwill to scramble up the long dark stairs to where our good dinner of cold lamb, and chickens, and ham, and hot potatoes, was spread out … When dinner was over we were so tired and sleepy, we made pillows of our cloaks, and lay down on the flags, all in a row like sheep … except Mama and Mrs Morrison who sat bolt upright on two uncomfortable chairs. But any attempt to go to sleep was vain, for Emmy crept quietly about from one to another … whispering mischief in our ears and making us laugh.52

The Greys were relaxed and full of life because they believed in a version of Christianity which emphasised love. Other Victorian Christians, such as Calvinists, were oppressed by feelings of guilt and sin. The Greys were convinced of their forgiveness and redemption by Christ, which gave them confidence, hope and an immense compassion for others. Among Victorian families, they most resembled the so-called ‘Clapham Sect’, of which William Wilberforce was a member.

Like the Clapham group, the Greys were members of the Evangelical wing of the Church of England. The established church had a wide range of belief within it, from the Anglo-Catholics or ritualists, whose beliefs and services were very similar to those of the Roman Catholics, to the Evangelicals, whose beliefs were very close to Nonconformists like the Methodists and the Baptists. Evangelicals believed that human beings were innately sinful but that they could be forgiven through repentance and ‘turning to Christ’. Christ had saved sinners through his death on the cross, and accepting Christ as Saviour (described as conversion or rebirth) would lead to new life.

Hannah Grey, although brought up as an Anglican Evangelical, had received some of her early education from a Nonconformist sect, the Moravians. It was said within the family that the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, had taken her on his knee as a young child, placed his hands on her head and pronounced ‘a solemn and tender benediction’.53 This was impossible, since Wesley had been dead for several years before Hannah was born, but the story does show the reverence the family had for John Wesley.54

Josey and Hatty’s nurse, Nancy, who was a Methodist, sometimes took them to her own chapel.55 There they would have sung great hymns, such as ‘Guide Me, Oh Thou Great Jehovah’ (Cwm Rhondda) and Charles Wesley’s ‘Love Divine, All Loves Excelling’. They would have sat through the long sermons delivered from the high and imposing central pulpit. Usually this would be delivered by the ‘circuit’ minister but occasionally a lay preacher gifted with powerful oratory would come to plead with sinners to repent and turn to Jesus.

In the 1830s and 1840s Methodism was gathering many new converts, who testified to their experience of ‘rebirth’ during the services and at class meetings. Josephine was so affected by this that she later insisted that she was ‘brought up a Wesleyan’.56

In fact John Grey took his children to the local parish church in Corbridge every Sunday. Hatty remembered that she and Josey ‘used to trot along to church, each with hold of one of Papa’s hands, who took such long steps that we had to run like little dogs by his side’.57 It was a long walk for children – almost 2 miles. The Grey children were taught Christian toleration. John and Hannah had learned to value the teaching of other churches besides their own, and were not hostile or disparaging of Christians from other denominations.

Throughout her life Josephine preferred not to identify herself with any one church. Her experience of attending Anglican services made her very critical of them. The preaching did not impress her at all. Referring to her religious crisis, she wrote that the minister ‘taught us loyally all that he probably knew about God, but [his] words did not even touch the fringe of my soul’s deep discontent’.58 This was to be the pattern of her life; she rarely found that Anglican ministers understood her concerns and so she remained on the fringes of the Church.

What Josephine valued was ‘vital Christianity’ and the freedom to develop her own ideas about God. She also adopted millenarian beliefs that the world was entering a time of evil, war and unbelief from which it would be rescued by the Second Coming of Christ. The doctrine that this Second Coming was imminent was preached by Edward Irving, who gained many followers in the English border country during the years of Josephine’s childhood. She and Hatty were taken to an Irvingite ‘camp meeting’ at Barmoor, 5 miles from their home, ‘in a cart with straw in it and a sack to sit on and we used to sit and hear the words and “prophesyings” of … those gifted men’.59 The meeting would have featured miraculous healings and speaking in tongues, and its powerful effect on children is not hard to imagine. In adult life, especially when overwhelmed by problems and setbacks, the prospect of ‘the great Deliverance’ and ‘the New Dispensation’ gave her hope for the future.60 The Second Coming was ‘the advent of the Day which we long for’.61

Education for Girls

Josephine went to a boarding school in Newcastle which her sister Fanny had attended. Hannah used to visit by train and sometimes sent them tuck boxes.62 It was run by a woman called Miss Tidy who became a friend of the family but had little to equip her for the task, beyond what Josephine described as ‘a large heart and ready sympathy’.63 She was ‘not a good disciplinarian’. When Hatty joined the school she spent much of her time drawing, including humorous illustrations in her teacher’s copy of the History of the Italian Republics.64 Hatty did not like school and left after only two years; Josephine stayed longer.65

Apart from that, the sisters were educated at home by governesses and by their mother Hannah, who ‘would assemble us daily for the reading aloud of some solid book, and by a kind of examination following the reading assured herself that we had mastered the subject’.66 This was a typical education for girls at that time, and not a very satisfactory one. Among Victorians it was a common view that there was little point in teaching girls any academic subjects, since they would grow up to have a domestic role as wives and mothers. Even though Hannah insisted that ‘whatever we did should be thoroughly done’, Josephine had deficiencies in her education which she rectified herself (with great success) in adult life.

It is surprising that John Grey did not do more for his daughters, since his own mother Mary Grey sent both his sisters to school in London. There is a family story that his sister Margaretta, frustrated that women were not allowed inside the Houses of Parliament, dressed up as a boy in order to gain entrance.67 John Grey also made sure that the children of tenants on his estates received an education. However, his high expectations of his daughters and the freedom he allowed them compensated a great deal for the gaps in their education. They were treated as equals within the home, and John discussed ‘all matters of interest and importance, political, social, and professional, as well as domestic’ with his wife and daughters.68 This gave Josephine a wide knowledge of social and political issues, and also an unquenchable confidence in her own value as a woman. This was a great gift, since so many Victorian women were brought up to see themselves as weak and inferior to men.

Josephine would have adored the chance to go to university, but it was never offered. She was, in fact, born just in time to achieve that goal, since Bedford, the first women’s college, opened in 1849, when she was 21. The campaigner Barbara Bodichon, born in the same decade as Josephine, attended.69

Margaretta Grey saw the dangers for the daughters of wealthy families of ‘too abundant leisure’ and activities like ‘visiting, note-writing, dressing and choosing dresses …’ instead of having ‘any real and important purpose’ in life.70 She criticised most female schooling as ‘a broken, desultory education, made up of details, of which the secondary and mechanical often have precedence of the solid and intellectual’. It is no surprise that Josephine’s own frustration, finally boiling over in her thirties, led her to direct her first campaigning efforts towards the higher education of women. But first came marriage and children.

Well-known Victorian Women – Who Were Josephine Butler’s Contemporaries?

Born more than 10 years earlier

Born within 10 years of her birth (1828)

Born more than 10 years later than her

Harriet Martineau

Journalist and author

Josephine Butler (1828–1906)

Feminist campaigner

Millicent Garrett Fawcett

Women’s suffrage campaigner

Charlotte Brontë

Novelist

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827–1901)

Feminist campaigner

Emmeline Pankhurst

Women’s suffrage campaigner

George Eliot

Novelist

Catherine Booth (1829–1890)

Salvation Army co-leader

Florence Nightingale

Nursing reformer

Isabella Bird (1831–1904)

Traveller and author

Elizabeth Gaskell

Novelist

Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904)

Feminist campaigner

Harriet Taylor Mill

Feminist campaigner

Anne Clough (1820–1892)

Women’s education campaigner

Charlotte Yonge (1823–1901)

Novelist

2

Josephine Meets George

George Butler

All the Grey daughters married, and Josephine wrote a touching account of the way they parted from their father:

… the visit paid in the morning to the bride’s room, the long, tender, silent embrace, and the throbbing of his strong heart, which betrayed his emotion. ‘Father, you have other daughters left,’ it was sometimes remarked; the only reply was ‘My child’ and a moment’s closer grasp to his heart.1

In some cases the daughters left home for the first time to live abroad. Hatty was to live in Italy after her marriage to a wealthy banker, Tell Meuricoffre. Their sister Eliza moved to Hong Kong with her husband, William Morrison.

Josephine herself, however, did not stray further than Oxford after her wedding, nor did she marry a rich man. George Butler, although in his late twenties, was still to make his career when she met him. He was not personally ambitious and appears to have been rather indecisive.2 In his youth he was quite a disappointment to his father, the Dean of Peterborough, who had previously been the headmaster of England’s top public school, Harrow. As a Harrow pupil, George did not distinguish himself (although he won a prize for Greek) and later recalled that ‘he was considered to be extremely good at “shying stones” and could hit chimneypots far better than the other boys’.3

At Cambridge University, he enjoyed the social life, was ‘attracted by music, art, out-door exercises, and athletics’, and neglected his studies.4 George, in short, had a healthy love of life and revelled in sport, games and physical exercise. He enjoyed risky climbs and jumping into cold water ‘hissing hot’ which in his opinion ‘helps one to resist the chill of the water, and brings about a speedier reaction, and that glow which is the bather’s delight and reward’.5

His father intervened, and withdrew George from Cambridge. After a period of five months studying with a private tutor, he moved to Oxford to study Classics. George had decided to turn over a new leaf, and gained a first class degree in 1843. He, characteristically, later described this time as his ‘owlish phase – read all day, spoke little, ate little, walked much, wrote Latin letters to my friends, and was generally very disagreeable’.6 During the next four years he stayed in Oxford, studying, teaching and leading reading parties in the vacations.

He was also private tutor for several months to Lord Hopetoun, the son of an aristocratic family.7 None of these activities amounted to a career, so he was relieved in 1848 to move to Durham University as a tutor in residence. He enjoyed teaching and was resisting pressure from his father to be ordained as a minister in the Church of England. He later explained some of his reluctance:

I don’t like parsons … if I were like some of them that I know, I should cease to be a man. I shall never wear straight waistcoats, long coats and stiff collars! … Great strictness in outward observances interferes with the devotion of the heart.8

George was a questioning, sceptical member of the Church of England. His experience of the Church was stifling, and his father’s position as a Dean was not a beacon to follow but a shadow over his hopes of finding a different career. The Dean hoped that the ‘clerical atmosphere’ of Durham would have a positive effect on George, but he immediately disliked it, since Anglo-Catholicism, with its emphasis on ritual and ceremony, was popular. George much preferred ‘inward conviction and fervour’ to outward display, and he had also made many friends at Oxford who were liberal ‘Broad Church’ Anglicans.9

The Path of True Love …

Even though Josephine wrote a biography of her husband, she never gave an account of their meeting.10 There has been speculation that Josephine could have met George in Durham, while on a visit to her brother Charles, who was a postgraduate student there.11 However, Charles was awarded his MA in February 1849 and Josephine was absent from home (probably for medical treatment in London) for seven months that year.12 There would have been a long gap before Josephine and George met again.

A recently discovered letter from George’s sister, Louisa, suggests a later date – June 1850. Louisa tells her youngest brother Monty about George’s passion for Josephine Grey, who ‘lives north of Durham, is very beautiful, plays divinely, is clever, sensible and altogether one of those Phantoms of delight’.13 George ‘fell in love with her at a ball in June and ever since, his love has waxed warmer and more warmer [sic]’.14

We know that Josephine was the belle of many balls and that George was athletic and probably an excellent dancer. George must have told Louisa the story of how he met the beautiful Miss Grey, with whom he was now helplessly in love. He began writing love poems to Josephine in October 1850, after his first visit to Dilston.15

George’s poems were written in his room at the top of Durham Castle tower. He transcribed them in beautiful copperplate handwriting and presented the volume to Josephine on the tenth anniversary of their engagement.

The Rose of Dilstone a Song

O twine for me no second wreath;

The jasmine, nor the eglantine.

I’d seek no broom, nor flowery heath,

Were the wild rose of Dilstone mine.

’Mid feathery ferns and liched rocks

Beneath the silvery birches shade,

Uninjured by the winds and shocks

How gracefully it rears its head!

Its beauty glads the passer-by

Its fragrance fills the vale of Tyne;

No other rose, no flower would I,

Were but the Rose of Dilston mine.16

A second poem, ‘The Rose and the Primrose’, is addressed to both Josephine and Harriet and contrasts the ‘brilliant tints’ of the primrose who ‘everyone admired’ with the modest ‘loveliness and heavenly grace’ of the rose.17 Those early conversations and outings with the sisters must have been entrancing, and George felt as if he had come home. He instantly fitted into their family life, and enjoyed all their outdoor activities, especially horse riding and hill walking.

In a third poem, ‘The Early Morn’, written at Dilston, George celebrates the beauty of the landscape, but ends on a note of desolation:

And I am driven forth, alas.

To wander cheerless and forlorn.

In vain for me the words are drest

In autumn’s hues, fair nature’s pride –

The thoughts that rise within my breast

Will not be stifled nor denied

No more can nature give relief,

Nor art her treasures ope to me,

For all my joy and all my grief

Is centred, Josephine, in thee.18

Josephine had rejected his early advances – he had been too eager. Back in Durham, he recalled ‘thy just reproof/and saw thy slow retreating form’. He ‘cursed my faltering tongue’ and resolved to take ‘the path of duty – harsh and stern’.19 To win Josephine, he would have to restrain his passion and move in step with her.

He was so successful that, less than three months later, Josephine accepted his proposal and they became engaged in January 1851. George had secured a new post, as Public Examiner at Oxford University, and would leave Durham at Easter. Although this post was part-time it was better than the ‘drudgery’ of the work in Durham and he had many friends and better prospects in Oxford.20

At this transitional stage of their lives, we can look not only into George’s heart, but also into Josephine’s since she used her correspondence with her sister Eliza in Hong Kong ‘as a sort of safety valve’ in which she could ‘put down all kinds of things, bad as well as good’.21 Her letters offer ‘a rare insight’ into the worries, fears and joys of ‘a young Victorian woman about to be married’.22

The early months of their engagement were anxious ones for Josephine. She confessed to Eliza that although they wrote to each other a great deal, ‘I feel rather a difficulty in getting on with him when he comes here first of all’.23 Partly this was because she did not see him very often, so ‘there is always some ice to be broken every time’. But she is frustrated that he seems to be ‘very guarded always … I don’t see why he should not come out with his feelings to me sometimes. If I did not exercise a childlike faith in the existence and strength of his affection for me, I might sometimes doubt it.’ Knowing the true strength of George’s feelings, it is easy to see that he was afraid of another rebuff if he expressed them too strongly. Victorian conventions decreed that physical contact, even between engaged couples, had to be very limited. He was also nine years older than Josephine – an age gap of which they were both strongly aware. Josephine told Eliza, ‘He is 32 nearly … rather too old I think.’

When Josephine wrote this letter, in March 1851, she was anticipating a long visit from George over Easter. He was staying at Dilston prior to his departure for Oxford. A dressing room had been turned into a study for him so that he could read each morning in preparation for his new job. (Quite a daunting one, since the Public Examiners conducted oral questioning of candidates in front of an audience.) Josephine was full of trepidation: ‘I hope we shall get over our fear of each other after he has been a few days in the house.’24 Hatty was at Milfield Hill, and ‘I feel so “friendless” without her, and I need her to back me up’.

Hatty’s absence may well have been deliberate – Hannah also kept to her room, and John was out much of the time. In a move which was unusual and enlightened at the time, her parents deliberately made it possible for Josephine and George to get to know each other. George’s stay lasted six weeks and proved, of course, to be ‘a most delightful and happy time indeed’, as Josephine told Eliza in the next letter.25 ‘I am so glad of this visit for we did not know each other well enough before … George and I have had to keep house together – and I do so admire and like the domestic part of his character which has been thus drawn out.’ Her fears about his age were banished now that he was ‘so playful and merry … he is just like a boy and confesses in such funny innocent ways how … in love he is’. In fairness she had to confess this to Eliza since ‘I wrote in rather a different strain last time’.

Strict convention and their own principles would have stopped them sharing a bed or having sex, but their closeness from this time onwards must have made the transition easy and happy after their marriage. Josephine was pregnant within a few weeks of their wedding in January 1852 and spoke of herself as ‘the happiest of women myself in all the relations of life’.26

Prelude to the Wedding

Passionate letters passed between them after George’s departure for Oxford. They regretted the delay before their wedding which, George said, ‘there would have been no reason for had we been rich’.27 During May and June, Josephine spent several weeks in London and they managed to meet up there. During this visit she sat for the fashionable London artist, George Richmond, who had painted the authors Charlotte Brontë and Elizabeth Gaskell.28 The result is a beautiful study which captures the ‘rapt, self-possessed expression of a woman in love’.29

Although she had told Eliza that ‘I detest London’, she enjoyed her visit and took music lessons from Sterndale Bennett, the composer, who she liked ‘excessively … I get him to play to me a good deal.’30 She also made two visits to the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, first with Tully and her husband Edgar Garston, and second with her mother and a group of friends.31 She was surprised and overwhelmed (as everyone was) by the size of the building, the sheer number of exhibits and the crowds. In a long letter to Eliza in Hong Kong, she said little about the exhibits, but noted ‘the Crystal Fountain, a fountain of white glass which throws up jets of sparkling clear water’ and the ‘mounted policemen, whose beautiful horses stand like statues in the very thickest of the crowd, arching their necks and looking so calm and dignified’.32 They struggled to get out, ‘It is a terrible place for weariness – Mama was nearly dead and wanted to come away by the front entrance again but that is not allowed, and so we had to make her walk nearly half a mile of the South Transept before we could get out. We came home in the Carrs’ carriage very hungry and tired.’

They had dinner at Lord Mounteagle’s, and went to Kensington Palace Gardens and on the Thames before George arrived. Josephine confided to Eliza that she contrived to spend the evening alone with him when everyone else went to church, ‘we stood listening to a nightingale singing – actually a nightingale! … It was very sweet and the distant sound of the organ in the church … made it very delightful.’33 By the end of June, she was ‘delighted at the thought of getting away from hot London streets’ and made her first visit to George’s family home, along with Hatty, Emily and her parents.34 It was ‘a very jolly party’ and Josephine declared herself ‘delighted with the old Dean’.35

George had to spend the rest of his summer in Oxford, where the examinations were taking place. He saved the life of his friend Ralph Lingen when they went swimming in a river and he was caught by the strong current. It says much for George’s physical strength that he not only battled against the current himself, but was able to pull his friend to the bank safely.36

George’s sisters, Catherine and Emily, visited Dilston and were treated to one of the family’s favourite outings – a visit to Queen Margaret’s Cave, which involved a scramble down rocks, and lighting candles in the darkness to try to detect ‘traces’ of the Queen.37 Needless to say, they found none.

The Wedding of Josephine and George

With the wedding set for 8 January, Hatty started to worry about life without Josephine, ‘I really don’t know what we are to do without her, sweet little body … I am perfectly unfit to fill up even half the gap her departure will make.’38 At the end of the year she decided to keep a diary, which records precious memories of her sister’s last few weeks at home.39 The first entry describes ‘Josey the belle’ of a ball at Newtown Hall, Durham, on 20 November. After the dancing, the girls went shopping for the wedding. Hatty and Josey left Durham on 24 November and ‘met Mama in Newcastle, shopped all day’. They returned the following week, when their friend Meggy Carr joined them to choose bridesmaids’ bonnets. (Hatty and Emmy were to be bridesmaids, along with Meggy and George’s sister, Emily.)

George arrived at Dilston on 20 December and they ‘put up the wedding cards’ on 6 January, and held a dinner party for family guests, including George’s younger brother, Spencer. George Grey arrived from Milfield with his wife and baby. Hatty did not fail to note the presence of attractive and eligible men like Spencer Butler and John Blackett, with whom she had a ‘very nice chat’ the following day.

On the day of the wedding, 8 January 1852, Hatty put her sadness aside and enjoyed herself thoroughly. After breakfast she ‘pinned favours’ on the four groom’s men.40