12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

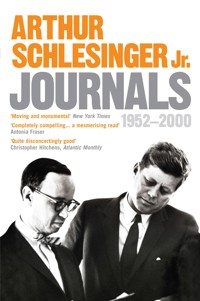

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Frank, revelatory, suffused with wit and humanity, Arthur Schlesinger Jr's journals offer an intimate history of post-war America, from his days on Adlai Stevenson's campaign team to his years in JFK and RFK's inner circle, through to the election of George W. Bush. They contain candid reminiscences of the defining events of our time - including the Bay of Pigs, the devastating assassinations of the 1960s, Vietnam, Watergate, the fall of the Soviet Union, and Bush vs Gore. They also offer an extraordinary window into the lives of the remarkable range of politicians, intellectuals, writers, and actors who were his friends - from the Kennedys to Kissinger and the Clintons, from Norman Mailer to Lauren Bacall and Marilyn Monroe. Together Schlesinger's journals form an astonishingly vivid portrait of American politics and culture in the second half of the twentieth century - one that only a man who knew everyone, and missed nothing, could provide.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Journals

ALSO BY ARTHUR M. SCHLESINGER, JR.

Orestes A. Brownson: A Pilgrim’s Progress

The Age of Jackson

The Vital Centre

The General and the President (with Richard H. Rovera)

The Crisis of the Old Order: 1919–1933 (The Age of Roosevelt, Vol. I)

The Coming of the New Deal: 1933–1935 (The Age of Roosevelt, Vol. II)

The Politics of Upheaval: 1935–1936 (The Age of Roosevelt, Vol. III)

Kennedy or Nixon: Does It Make Any Difference?

The Politics of Hope

A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House

The Bitter Heritage: Vietnam and American Democracy, 1941–1966

The Crisis of Confidence

The Imperial Presidency

Robert Kennedy and His Times

The Cycles of American History

The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society

A Life in the 20th Century: Innocent Beginnings, 1917–1950

War and the American Presidency

First published in hardback in the United States of America in 2007 by the Penguin Press, Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA.

This edition published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © The Estate of Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., 2007

The moral right of Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN: 9781782395447

Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction

1952

1953

1954

1955

1956

1957

1959

1960

1961

1962

1963

1964

1965

1966

1967

1968

1969

1970

1971

1972

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

2000

Index

About the Editors

INTRODUCTION

In the fall of 2006, our father, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., approached us—his two oldest sons—about editing for publication his private journals. We were both surprised by his request, for he had never asked us to collaborate on any of his literary and historical projects before, and touched that he trusted us to review some of the most important recorded moments in his life. Certainly, we thought, he might have more ideally chosen an experienced historian or scholar for this work. And frankly, we wondered whether we, as his sons, could bring a useful independent sensibility to the editing process and judiciously appraise his journal entries in an appropriate manner. Apart from these initial misgivings, we had also never seen his diaries, had no idea what condition they were in, and possessed little sense of their contents.

Our father’s agent, Andrew Wylie, had initially come upon our father’s journals in an authorized inspection of his office one day earlier in 2006, when he found them all bunched together on a shelf above a small icebox. They amounted to more than 6,000 pages in entirety and comprised almost half a century of his activities, from 1952 to 2000. We first saw the journals in November 2006, in Mr. Wylie’s office, where we found them piled on a number of large tables in dozens of file-folders, each containing a year’s worth of his reminiscences in clean typewritten form. (It turns out that our father’s intrepid secretary for years, Gretchen Stewart, had carefully transcribed them through the decades.) What we were seeing was a jewel box of memoirs.

After a quick look, we were riveted. A few perusals of the documents gave us fresh knowledge of our father’s life that we had not been privy to before, as well as the pleasure of reading a superior diarist with a masterful style. His journals were full of rich, witty and revelatory observations about the famous events and larger-than-life personalities in American life for nearly five decades. We decided then and there to do the project.

From the start, our father’s publisher, The Penguin Press, had made the decision to publish the journals in a one-volume, abridged edition for the occasion of what would be our father’s ninetieth birthday, on October 15, 2007. This gave us approximately three months to reduce the 6,000 pages to a more manageable 1,000, thereby extracting only the most illuminating and widely heralded episodes our father described. We split the burden of editorial oversight, passing the thousands of pages back and forth between us in New York and Cambridge, together making the occasionally agonizing decisions over what to include and what to leave behind. Our two intrepid Penguin Press editors, Scott Moyers and his deputy, Laura Stickney, contributed further suggestions and emendations.

Though the notion of cutting three quarters of our father’s extraordinary journals was daunting, the narrative magic of the book helped resolve many selection problems for us. We were ineluctably drawn to the unique series of transfixing, amusing, provocative, sardonic, moving and revealing encounters that he had with the foremost progressive (and occasionally conservative) figures of his time. It is not an exaggeration to say that his broad circle of friends—both men and women—virtually dominated the political, social, artistic and literary landscape of the post–World War II era.

Our father’s journals are not necessarily personal recountings of his lifetime pilgrimage, along the lines of, say, the diaries of Edmund Wilson. While he did write about his family and his two wives, his mind was always most keenly focused on the events of the day. This was likely due to his penchant as a historian for concentrating on what he considered the crucial details of his time—but surely, too, it was also due to his proper New England upbringing which frowned upon writing much about intimacy. In any case, we think it is fair to say that he was primarily trying in these journals to give recognition to the most notable happenings in his own American lifetime as he saw them—what a collection of stories, anecdotes and tales he was able to recount.

Of course, the journal entries always reflect his particular mood at the time he was writing. At any given hour, his voice might be full of indignation, pleasure, shock, fun, anger or happiness. This is the way of a diarist. Inevitably, the candor of some of these reflections may strike friends and acquaintances as indiscreet. For example, our father occasionally quotes intemperate or rash remarks made by his associates about others—remarks they may later regret. Also, he often changed his mind about his associates. That is unavoidable in such annals. Most important, in our father’s mind, was always to be truthful to history and, for the most part, he was singularly balanced in his judgments.

It is astonishing to remember that our father wrote some thirteen books during the period of these recollections—even while logging these diaries, teaching at Harvard, helping out on political campaigns, engaging in topical debates, participating in the Kennedy Administration, serving as a university professor at the City University of New York, leading a crowded social life and meeting crushing obligations of every kind. Over the course of the years covered in these journals, he authored the following tomes: The Crisis of the Old Order (1957); The Coming of the New Deal (1958); The Politics of Upheaval (1960); Kennedy or Nixon: Does It Make Any Difference? (1960); The Politics of Hope (1963); A ThousandDays (1965); The Bitter Heritage (1966); The Crisis of Confidence (1969); The Imperial Presidency (1973); Robert Kennedy and His Times (1978); The Cycles of American History (1986); The Disuniting of America (1991); and A Life in the 20th Century (2000).

His diaries offer a somewhat different sense of the rhythms of American life over this half century than his books. They provide a vibrant and almost panoramic view of his country through the voices of the giants he both admired and occasionally disdained. As the United States alternatively went off- and on-track through this turbulent period, our father’s idée fixe was, from the start, to count the passage of time in America via the quadrennial Democratic presidential conventions which he almost always attended, lovingly commented upon, and sometimes personally influenced. For him, these conclaves marked the great moments of possible change in the country, but also signaled the time when everyday citizens had a chance to vent their feelings and take action in a democratic way. Of course, for him, these were also terrifically entertaining and exhilarating affairs.

Just as fascinating for our father, as these journals attest, were the political campaigns that followed the conventions. Like an anthropologist picking through the scattered debris of an ancient site, our father observed these races carefully and assessed their building blocks, their strategic imperatives and their often messy internal structures. He analyzed the strengths and weaknesses of the contestants. Beginning with his days on the stump with Adlai Stevenson, he frequently took part directly in these crusades, getting an adrenaline rush from campaign work—authoring speeches, advising on policies, advancing strategies, delivering addresses, winging around the country with the candidates. As a historian who had written about the presidencies of Andrew Jackson, Franklin Roosevelt and John Kennedy, he knew quite well the ins and outs of political warfare in America. But he learned something new and vital for his own scholarly uses from every new cause in which he participated or advised.

What these ventures also did was to introduce him to a remarkable lot of men and women who directly influenced his life: Adlai Stevenson; Averell and Pamela Harriman; John Kenneth Galbraith; Hubert Humphrey; John, Robert and Edward Kennedy; Robert McNamara; Katherine Graham; George Kennan; Jackie Onassis; Ted Sorensen; Lyndon Johnson; George McGovern; Walter Mondale; Henry Kissinger; Bill and Hillary Clinton; and the list goes on. There were also foreign leaders and intellectuals he became acquainted with through these circles, ranging from Romulo Betancourt, one-time president of Venezuela, to German leader Willy Brandt, to former British prime ministers Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher, to the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, and others. And there were the mesmerizing political writers of the period, such as Walter Lippmann, Joseph Alsop, Rowland Evans, James Wechsler, Richard Rovere—and their sundry brethren—whom he also got to know.

But his omnivorous interests drew him beyond the political battle lines into other arenas. His almost voluptuous eyes and soul led him to rove widely and far afield. He adored American movies and did film reviews for various publications. He became close friends with such vibrant movie personalities as Lauren Bacall, Rex Harrison, Angie Dickinson, Marlene Dietrich and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. He relished the theater, especially Broadway musicals. He spent many evenings with composers and lyricists like Leonard Bernstein, Alan Jay Lerner, and Betty Comden and Adolph Green. He became a cohort to a slew of writers across a wide spectrum of the literary scene, including the likes of Norman Mailer, Carlos Fuentes, William Styron, Edna O’Brien, Edwin O’Connor, Joan Didion, Edmund Wilson, Saul Bellow, Mary McCarthy, Lillian Hellman and Philip Roth—an endless parade of talented artisans. The importance of these friendships—and the way they so deeply enhanced his life—are all documented in these journals.

Our father died of a heart attack on February 28, 2007, while dining in a New York restaurant, just as we were finishing up our labors on his diaries. His death came as a shock to us, because, despite his infirmities—including the onset of Parkinson’s disease, which had rendered his speech almost unintelligible—his mind remained as sharp as ever. He could still turn out an occasional wicked and penetrating op-ed piece when the spirit seized him. And he was very helpful to us when we consulted with him, from time to time, in the months before his death, on what he wanted to keep or excise from his accounts. However, there was astonishingly little he wished to take out. As he once said, “What the hell, you have to call them as you see them.” Our consolation in the end was that he lived his life as he wanted to, to the fullest, until the very last moments—and that he gave us the treasure of these journals, reminding us once again how remarkable his time on earth really was.

—Andrew Schlesinger and Stephen Schlesinger

March 29Washington

Joe Rauh offered me his ticket for the Jefferson-Jackson Day dinner. It turned out that George Ball had given his ticket to Libby Donahue; so I suggested we go together. I borrowed a black tie from Phil Graham and put on a white shirt, trusting that with a dark blue suit on I would look properly dressed in the half-light. Making our way to our table, we became entangled in one of the head table lines. In quick succession came the three nicest men in public life—Wilson Wyatt, Adlai Stevenson, Averell Harriman. Averell suggested that we go out for a drink afterward.

The speaking was indifferent. The Armory was too vast for people to feel much involvement in what was going on. [Sam] Rayburn gave a speech with a nice human quality. [Alben] Barkley was loud and vigorous.

The meeting warmed up a bit when President [Truman] began. It was a good, fighting campaign speech, I thought; nothing new, but lively, and delivered with humor and composure. Libby, bored, whispered to me toward the end, “This is the most utterly meaningless speech I have ever heard.” At that moment, the President announced that he would not be a candidate for reelection, would not seek the nomination. The audience was stunned and confused. Some people reacted automatically by applause (as Adlai said in the car later, “They applauded with really macabre enthusiasm”); others shouted “No.” I found myself shouting “No” with vigor; then I wondered why the hell I was shouting “No,” since this is what I had been hoping would happen for months. Still the shouts of “No” seemed the least due to the President for a noble and courageous renunciation. He hurriedly finished the speech and disappeared, leaving the audience still stunned. Half the people did not seem to know what had happened.

We went out to meet Averell. He said that he had asked Adlai to accompany us. Adlai, in the meantime, was surrounded by a screaming mob of newspapermen, photographers, radio people, etc. This went on for 15 or 20 minutes. Finally we pulled him out and got into Averell’s car. Adlai told me that he was completely astonished by the President’s decision.

The bar [at the Metropolitan Club] was closed; but we went upstairs to talk. Adlai, looking very tired, tending to bury his head in his hands, was obviously appalled at the great abyss opening up before him. He kept saying that he didn’t want to be a candidate. Running against Taft was one thing; but he wasn’t certain that Eisenhower would ruin the country. Averell at this point became very eloquent. Eisenhower’s nomination, he said, would eliminate foreign policy as an issue, but this would make domestic policy all the more important. Averell went on to say how much a successful foreign policy depended on a successful domestic policy, and how unreliable an Eisenhower administration would be. Adlai simply groaned. Finally Averell said, “For the sake of the party and of the nation, Adlai, you’ve just got to run. There isn’t anybody else.” Adlai groaned, looked as if he were going to cry, put his head in his hands, and finally said, half humorously, half agonizedly, “This will probably shock you all; but at the moment I don’t give a god damn what happens to the party or to the country.” Averell, who was not shocked, correctly ascribed these sentiments to fatigue, confusion, an impending cold; and we shortly afterward dispersed.

July 21 [Chicago Democratic convention]

We heard Adlai’s enormously effective speech of welcome to the convention (really a speech of keynote, nomination and acceptance rolled into one) and Paul Douglas’s noble if heavy speech on the Korean War. Adlai’s speech even made a dent on the strongly anti-Adlai atmosphere of the Harriman headquarters.

July 22

This morning at 7:45 I was awakened by a phone call from Averell. “Have you had a chance to see that fellow yet?” I said no. Averell said that he wanted to give me the picture—in general that he was convinced that he (Averell) had “great underlying strength,” that “if Adlai were still a liberal,” he should join with the other liberal forces to support Averell, and that there was real danger, in case of a deadlock, of “the Boss’s” deciding to run; “that’s what a lot of people have been working for.” Jim Loeb and FDR Jr. had tried to see Adlai, but he would not see them. “You’re the only contact I have.” The conversation went on for about ten minutes. Averell seemed calm, resolute, hopeful, not too bitter at Adlai.

At 3:15 I finally made contact with Adlai and talked for about half an hour. It was a long, meandering conversation, revolving around the following points.

1.He kept wondering whether he should make a Sherman statement [a categorical rejection of candidacy as made by William Tecumseh Sherman]. FDR Jr. had apparently suggested it. Adlai’s reactions were that it would help [Estes] Kefauver more than it would Harriman; and that it would terminate his own political career. After all, Sherman was 68 years old when he issued the statement, and he did not have much of a political future. “I do hope to continue to be able to do things for my state and party.”2.He said he had instructed his alternate to vote for Averell; but the reports that came to him of Averell’s political strength were very discouraging. If Averell were nominated, he said, the party would take a terrible beating. Kefauver would do better. He felt that Averell had been misinformed about his political strength.3.He sounded a bit resentful of the reports of Averell’s irritation with him. “I’ve done everything I could for Averell,” he said, then added, “short of coming out for him.”4.He sketched very clearly his own design as to how he hoped things would work out. He did not want the nomination, he said, and, if he had to take it, he hoped it would come only because the available candidates all recognized that none of them could win. Having mutually exhausted each other, he hoped they would all come to him and ask him to run. Instead, he said, it now looked as if he might get the nomination with the ill-will and abuse of the other candidates. I said that he must understand that the irritation on the part of the other candidates was only natural, but that it need not harden into a permanent grudge, and that I hoped he would call Averell as soon as the nomination looked certain.5.He seemed very much opposed to doing anything which might drive the South out of the party. Averell, he said, was a “disunity” candidate; the party needed a “unity” candidate against Eisenhower. The southern governors had told him at Houston that Harriman was as bad as Truman; that if they had to have this kind of president, they would rather have the real thing. It is clear that on this issue Adlai belongs with those who see no great moral point involved in pushing the South around on these issues.My overall impression was that Adlai would reluctantly run.

July 23

Averell came in dog-tired from talks with delegates, etc, and I had a tête-à-tête dinner with him. He seemed, on the whole, to be in excellent condition, if weary, though his prospects by this time had come to seem fairly hopeless. At one point, I said, “Win or lose, you have done a fine job, and it was all worth the effort.” “Don’t say, ‘win or lose’” he said, “I am not deceiving myself about my chances. I know they are small. But I think there is enough chance to justify my carrying on the fight.”

July 24

While waiting in the Harriman dug-out, we saw Kefauver give an effective TV interview, protesting the boss-ridden convention, denouncing the phony draft of Adlai Stevenson, and calling on all his listeners to deluge their delegates in Chicago with wires and phone calls telling them to vote for Kefauver. He seemed to have the smell of victory in his nostrils. This confirmed my feeling that there was no hope in the Kefauver discussions, and it accelerated my growing and now urgent conviction that Harriman should have a meeting with Stevenson.

Averell listened, then asked John Carroll and John Kenney their opinions. As we discussed it, Hubert Humphrey arrived for a general strategy discussion. This proceeded for a few minutes when Averell beckoned me out of the room, and asked me to set up an appointment with Adlai as quickly as possible.

July 25

I hurriedly showered and shaved and, with no time for breakfast, jumped into a cab and went out to 1448 North Lake Shore Drive and to an apartment on the 17th floor, currently occupied by the Iveses, Adlai’s sister and brother-in-law. Averell and John Kenney were there.

[Adlai] seemed calm, cheerful and business-like.

Adlai declared that he definitely did not countenance any of the pressure moves on his behalf. He had not sought the nomination; he did not want it; if he had to take it, he wanted only a genuine draft. Yet he had no doubt that Arvey’s people, after assuring him they would not do anything to advance his cause, went out and employed all kinds of pressures. As he talked, he made it clear that he had little use for Arvey, and that he was eager to do what could be done to improve his relations with the liberals.

There was some discussion of the vice presidency. Adlai mentioned the names of Kefauver, [John] Sparkman, Mike Monroney and Barkley. The Vice President, he said, had to be thought of from two angles; first, how useful he would be before the election—how much strength he would bring to the ticket; and then how useful he would be after the election—how effectively he would serve the President as liaison with Congress. Adlai thought that Kefauver would add the most immediate strength but might be a pain-in-the-neck after election (“I don’t know why it is,” Adlai said; “Kefauver has never done anything to me, yet somehow I just instinctively don’t like that fellow”). Sparkman and Monroney, he thought, would be excellent vice presidents but would create political problems. Toward the end, I threw in the name of FDR Jr. Adlai’s reaction was interested, though somewhat fearful about southern reactions. (It later occurred to me that a Stevenson-Roosevelt ticket would be impossible, since both ends of the ticket would be divorced men.)

I think our one mistake in the conversation was not to lay more emphasis on the [adverse] consequences of a southerner on the second spot in the ticket. We did not do so because all of us more or less agreed that Sparkman was the best person among those whose names were being considered. Adlai kept showing special solicitude for the southern situation, he said more than once that he understood that Texas, Virginia, South Carolina and Florida might flop over into the Republican camp, and that it was important to win them back. When I pointed out that their total electoral votes were equal to a couple of northern industrial states, the point seemed to register intellectually rather than emotionally.

Stevenson was clearly much worried (as well he might be) over his relationship with Truman, whom I think he regards as a kind of Old Man of the Sea, clinging to his shoulders while he tried to run a campaign of his own. He repeated several times his desire to dissociate himself from Truman and his administration until Averell finally pointed out that Truman was a very popular man who would be an invaluable asset in the campaign.

The [meeting] was conducted on the assumption of Stevenson’s nomination. Averell said about his own position substantially that he had not given up, that if he had been able to arrange the right kind of deal with Kefauver he would certainly have done so, that he had no immediate intention of withdrawal, but that he preferred Adlai to any other candidate next to himself and would, if necessary, use his strength to support Adlai against Barkley or Kefauver.

We left the apartment, ran a barrage of reporters and cameramen and went straight down to the Amphitheatre, arriving shortly after noon as the polling [for the presidential nomination was] about to commence. I spent the afternoon, alternating between the convention, the corridors and the Harriman dug-out, while the vote droned on. The completion of the first ballot showed Kefauver in a slight lead. As the second ballet went on, Stevenson seemed to be gaining some, but so did Kefauver; and there was considerable apprehension expressed over whether things were proceeding according to schedule.

Marian [Cannon, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr.’s first wife] and I had dinner at the Stockyards Inn with the Alsops, Suzanne Roosevelt, Prich [Edward F. Prichard, Jr.], Joe Rauh and the Claiborne Pells. After dinner we returned to the Amphitheatre for the last act. Averell [had now withdrawn], followed by [Governor] Paul Dever’s declaration for Stevenson, [making] it clear enough how things were going.

[Stevenson’s] nomination brought great cheers and excitement. Unfortunately it was followed by what seemed hours of singing before the President made his appearance. The crowd went wild when Harry finally came in—the brisk, relaxed, jaunty little man. His speech, unhappily, was tired and cliché-ridden, and delivered without his usual verve. But he—and we—got through it; and then he introduced Adlai.

The Stevenson speech was an extraordinary performance—a brilliant literary document, complex and carefully wrought in its composition, bearing the imprint of a highly individual, complicated, sensitive and distinguished personality. It had too much business in it about how he had not wanted the job and was not up to it; but it also had wonderful passages of political polemic; and it was suffused throughout with a sense of the immensity and impenetrability of the crisis of our time. He delivered the speech with great polish and dignity. The crowd listened with fervent attention, applauded frequently and gave him a great ovation at the end. I found myself both impressed and troubled by the speech. It was like watching an acrobat accomplishing dazzling and dangerous leaps on the high wires; he always made the next ring, but each new try was nerve-wracking. I also could not help thinking about Jim Rowe’s remark that he was planning a book about the Stevenson administration to be called “Hamlet in the White House.” But, whatever else Stevenson is, he is an original personality in our public life; he is the start of something new.

July 26

I was awakened around 9:15 by a call from Averell who was trying to get in touch with Adlai. I gave him various phone numbers and street addresses; and he invited us over to breakfast. We got there about 10. Averell was in good, urbane, cheerful form. He had some of the same misgivings about the speech that I had—and also about the whole shape of Adlai’s campaign. The only hope of winning in November, he said, was to go to the people and fight on the issues of the New Deal and Fair Deal; he knew it because he had spoken all around the country in the last two months, and these were the issues to which people responded. Averell fears that Adlai will attempt the kind of campaign that Walter Lippmann talks about in his column. If he does, he will lose; if the people want an Eisenhower, they will take the real thing.

August 8

On Monday, July 28, Harriman called to say that he had talked to Stevenson about my working on the compaign, and that Stevenson wanted to know how to get hold of me. On Tuesday Adlai called, and I said that I would stop at Springfield before leaving the Middle West. On Wednesday, Marian, the children and I got into the car and started driving, going along the beautiful gorge of the Mississippi, cutting across Iowa (Dubuque to Davenport) and arriving at Springfield Thursday evening. I spent all day Friday and half of Saturday there, leaving for Cambridge Saturday afternoon.

Adlai seemed in good shape, though a trifle overwhelmed by the multiplicity of problems suddenly descending on him. He looked well, was relaxed, made wry jokes, seemed reasonably belligerent, regarded the fact that he is not much known through the country as his main handicap and seemed determined to remedy this as quickly as possible.

The headquarters seemed suffused with a fear of “identification”—“identification” with the Truman administration, with labor, with ADA, with the liberals—indeed, with almost any group apparently except the South. There seemed to me an unreasonable concern with smoothing ruffled southern feelings—a tendency to bear with and explain away southern contrariness, while becoming quickly impatient with labor and the liberals.

Marian and the kids arrived in mid-afternoon. On the way to the garden I walked past the Governor’s office window holding the hands of Chrissie and Andy. Adlai, who was conferring with [Paul] Douglas, waved at us; then apparently told his secretary to tell the housekeeper that he wanted us all for dinner. So we all dined in the garden that night—Mrs. Ives, the kids and I at one table; Adlai and Marian at the other. Stephen and Kathy were wordless with excitement. When they came to say good-bye, we were in Adlai’s office. He took Kathy and Stephen over to a facsimile of Lincoln’s autograph [and an] autobiography and read them the portions dealing with his schooling. It could not have been nicer.

My general reaction on leaving Springfield was that Adlai was probably even more conservative than I had thought, perhaps, indeed, at this stage, the most conservative Democratic candidate since John W. Davis. His campaign seems currently oriented toward two groups:

1)The high-minded Republicans, who provided the margin of victory in Illinois and who—the Stevenson people seem to think—can be won away in quantity from Ike; and,2)The southerners, for whom solicitude is fairly constant. For both these groups one can emphasize the issues of foreign policy and, to some degree, of civil liberties. But economic and social reform clearly must be muted.The logic of this campaign is thus to softpedal the issues which really appeal to labor, the liberals and the minorities. To gain the South, in short, and a few dissident Republicans, there is a great risk of losing the industrial North. The assumption, of course, is that labor and the Negroes will have no other place to go. But they can always stay home—and they well may.

I left Springfield thinking that I would be lucky if I could get the candidate to mention the New Deal in the course of his campaign. Yet, on reflection, I probably overstated the gravity of the problem. Adlai Stevenson still seems to me a man who will rise to the necessities of any crisis. He is the one man in politics today who strikes an authentically new and fresh note. Eisenhower utters the clichés of the right, Harriman the clichés of the left (with which I agree, but which are clichés nonetheless); all the other candidates are equally uninteresting and sterile. Stevenson promises the possibility of adjourning the tired old debates, moving beyond them and ushering us into the post-Roosevelt era, toward which we are groping.

August 11 [Springfield, Illinois]

In the morning Carl McGowan and I had a session with Adlai on the speech schedule. This included some discussion about the Labor Day address in Detroit. He wants to say that labor has duties as well as privileges, etc., and he wants to warn labor against trying to take over the Democratic party.

There is a kind of Calvinism in Adlai. He has a natural and honorable dislike of the kind of speech which seeks to buy votes by making promises. But he recoils from this with a political puritanism which regards any popular political position (at least on the liberal side) as somehow immoral. He flinches from civil rights because it will be construed as a bid for Negro votes. Thus his whole desire is to lecture the veterans at the American Legion, to lecture the workers in Detroit, etc. When I noted this, he said, “Well, I would rather lecture them than try to win their votes by promising them material benefits.”

As I say, this is an honorable position. But it would be more honorable if he were as austere in his attitude toward special interests on the right as he is toward special interests on the left.

I spent most of the day working on Adlai’s Thursday speech. I had dinner with Scotty Reston. We spent two or three hours trying to sort out the varied and perplexing reactions to Adlai. Scotty thinks that Adlai and Ike are not unlike in some respects—both are good but not great men. He will vote for Ike in order to spare the country four more years of Yalta, Hiss, McCarthy, etc. (This position distresses me far less than it would have a few weeks ago. If we are going to have a Republican President it might as well be on the Republican ticket.)

August 12 [In Springfield, Illinois, the speech-writing team convened.]

My heart sank as the discussion proceeded; even Wilson [Wyatt] seemed to be endorsing awfully conservative positions. I finally decided that the purposes of this campaign were so remote from my beliefs that I had better confine myself to a technical role in the campaign and stay out of policy discussions. So I kept quiet for a time until finally we began to consider the question of the dangers of centralization and the revitalization of local government. This roused my Hamiltonian instincts, and I launched into an eloquent defense of the role of a purposeful central government in promoting our national life. Somewhat to my surprise, Clayton [Fritchey] vigorously supported me. We finally got the others (Wilson coming around first) to agree that there should be no implication that the revitalization of state and local government would materially reduce the size, cost or power of the present federal government. This would make it clear that the statement would not contribute to the vulgar clamor against the allegedly swollen and power-hungry bureaucracy.

I am not sure that I am right in my differences with Stevenson. It may be that this line is the future, and that I am an increasingly obsolescent New Dealer. But I cannot escape the conclusion that his conception of a responsible and sober business community is likely to stand up less well than the New Deal picture of a confused, selfish and irresponsible business community.

September 4

Yesterday morning I flew with the Governor’s party to Denver and thence to Los Angeles. The stopover at Denver was long enough to permit me to drive into town in one of the lesser cars in the motorcade. The crowds were practically non-existent. Nonetheless, I must confess that I get a great kick out of the political spectacle—the review of speeches in the plane, the arrival, the newspapermen, the local dignitaries and so on—all great fun.

The trip was uneventful until the Governor came on Scotty Reston’s story in the Wednesday New York Times supplying detailed information about the speech-writing group. This made him quite mad for a few minutes.

I think he feels really very sensitive to any suggestion that he does not write his own speeches. He spent most of the trip reworking the main Denver draft. As Carl and I made suggestions for certain cuts, the Governor protested plaintively about how his own best phrases were always cut out. Actually, of course, most of the speech was his.

September 10 [San Francisco to Los Angeles train trip]

I got up at 6:15 today, breakfasted with Ben Heineman, and went to the station along with Ben, Dick Rovere and Scotty Reston. This began a day of whistle-stopping large crowds, sunshine, corny pontifical introductions, wisecracks and seriousness from Adlai, the introduction of Borden [Stevenson] and John Fell to the audiences, and so on. I greatly enjoyed it—and so did the Governor, I think, though it wore him down a bit, and he affected a new horror at each new stop. I was particularly delighted by his proposal for a deal with the Republicans—“if they stop telling lies about us, we will stop telling the truth about them.” He told me that he had used it in 1948—but that he had heard it years before, and that it was an old gag in Illinois. New to me!

September 12 [Springfield, Illinois]

The Governor asked me to come to the Executive Mansion for dinner. Very pleasant. The Wyatts, Bill Blair, and the boys. After dinner, we immediately got down to business about the next trip. Carl, Dave Bell, Ken Galbraith, Jack Fischer and Sid Hyman joined us.

The Governor first read a very friendly letter from the President of September 10th. Truman said, among other things, that this was becoming “one of the dirtiest campaigns I have ever been in” but told the Governor that he should not mind. The letter was addressed by the way, “Dear Governor.”

Adlai then described his conception of the political problem. The liberal and the progressive record, he said, had been made on the western trip, now is the time to get back to the middle of the road. “We haven’t said a damn thing about cost of government, efficiency, economy, antisocialism, anti–concentration of power in Washington. The impression is that we are moving more and more to the left, that I am becoming the captive of the special interest groups [sic—interesting revelation of where he thinks the special interest groups lie]. Now I want some good hard licks on the conservative side, fiscal responsibility against waste and extravagance. I don’t want to be euchered out of that position. We mustn’t let them preempt the position of fiscal responsibility.”

These themes were repeated and developed at length. The thing he most wants to talk about, he says, is government economy, though he conceded that cost of living (inflation) should probably have priority.

September 18 [Springfield, Illinois]

I lunched with Wilson Wyatt today. He was in a fairly gloomy state. This morning he had gone to the airport to see the Governor off. Along the way he suggested some course of action to him. The Governor demurred, saying, “You know I didn’t want this job. I didn’t want to be nominated.” This is in part, of course, a manner of speaking for the Governor. Yet every once in a while he acts as if he were doing his entourage and even the country a favor by running.

In the evening Wilson held a strategy meeting. We were all pretty gloomy—a gloom accentuated by Wilson’s reading of secret and rather depressing figures from Elmo Roper. These figures show, by the way, that the Governor’s best chance is to turn left. We were all impressed by Averell Harriman’s analysis—that the thinking minority had been convinced, but that we had made very little inroad on the unthinking majority. The Governor has persuaded people; he has not excited them.

October 12

Last Tuesday (the 7th) we left for Michigan. Our first stop was Saginaw, a city apparently populated largely by juvenile delinquents. All the way into town, little monsters chanted “I like Ike.” The schools had been let out—a hideous error—and the hall where the speech was given was crowded with children. They set up an “I like Ike” howl when Adlai first entered and continued it at intervals throughout the speech. Scotty Reston said that it was the most ill-mannered crowd that he had ever seen.

The Governor was annoyed by all this, but concealed it pretty well on the platform. When he got back to the plane, he said gloomily, “Shaw was right, ‘Youth is too wonderful a thing to waste on children.’”

October 16

On Tuesday the Governor left for his last western trip. The reports from the trip increased our optimism. We are developing a technique of alternating high spiritual speeches (Salt Lake City, Los Angeles fireside) with rousing political speeches (San Francisco, Los Angeles rally); and the result is pretty effective. The Governor himself is still reluctant to be a demagogue—still reluctant to make broad and easy promises, or to flay the foe too hard—but he is coming along. Probably his own sense of timing on these matters is far better than ours anyway.

October 24 [The final campaign train trip]

I did not arise for the Niagara Falls whistle-stop at 7:15. But I did get up in time to hear the Rochester speech at 9:30—the one I had written desperately from midnight to 2:30 the night before. We had discovered at the last minute that the 24th was United Nations Day; we also wanted to meet more directly the increasingly vehement Republican exploitation of the Korean issue; so on the basis of material sent along by Dr. Frank Graham, I composed a sharp speech on the UN and Korea. It proved a great success—so much so that the newspapermen immediately demanded texts and made it their lead for the day.

October 25

I got up in time for the Hyde Park [New York] stop at 8 A.M. It was a beautiful, brilliantly sunny fall day, brisk and bracing. I have never seen the Hudson look so blue. The train stopped at the Hyde Park station, where Mrs. Roosevelt, Franklin and Sue [Roosevelt] and the Morgenthaus met us—also Dick and Eleanor Rovere. The Governor went off to Val-Kill for breakfast, while the Roveres took Carl and Jody McGowan and me to see the Library and the house. We finally found Herman Kahn who gave us an excellent swift tour.

Then to Poughkeepsie, where the Governor spoke from the balcony of the Nelson House to a disappointingly small and apathetic crowd. I had written a speech in which I tried to define his relationship to FDR and the New Deal. He had not made many changes in it, and it did represent an attempt to set forth a little of the Stevenson philosophy. It had read pretty well to me the night before; but it was certainly a flop in the morning. The Poughkeepsie audience evidently did not give a damn about Roosevelt. This was one of the few disappointing receptions we had on the trip.

Thence to Massachusetts. The first stop was Pittsfield, where Paul Dever, Jack Kennedy and a collection of Massachusetts politicians, volunteers, etc., all got on. We got to Boston about six. Marian, Kathy, Stephen and mother met me. I had not seen the kids since Labor Day, and they were a welcome sight. I promptly went home. Later we dined at Locke-Ober with Joe Alsop, Jack Kennedy, one of his pretty sisters, John Miller (London Times) and two or three other people.

October 28 [Stopover in New York City]

I spent all Tuesday working away at the [Biltmore] hotel, while Marian went motercading into New Jersey. The big problem was the Madison Square Garden speech. This speech raised a tough and typical question: should it be beamed to the local audience, which wanted a fighting rally speech? or to the great television audience, which would presumably want something more serious and statesmanlike? On the basis of a draft by Jimmy Wechsler, I had written a very good pour-it-on speech. Bill Wirtz had written a more serious and substantial speech.

After considerable discussion, it was decided to combine the Wechsler-Schlesinger and Wirtz drafts, striking on the whole a thoughtful rather than a pour-it-on note.

Marian and I dined at Marietta Tree’s, where we got into more or less violent arguments with the Alsop brothers over their now announced decision to vote for Eisenhower. I bet Stewart 25 that Stevenson would be elected. After dinner we went over to the Garden. We arrived by 9 o’clock; Adlai was not to go on until 10:30, but the Garden was already hopelessly crowded, and it was impossible even to get near it. All our elaborate badges and passes seemed to avail us not, until one of the cops recognized David Niven, who was one of our party, and we were waved on in.

I have never seen a more exciting rally atmosphere than Madison Square Garden that night. The crowd was tense, excited, hushed with expectancy. A number of speakers were warming it up. Harriman, for example, gave an excellent short speech and got a tremendous rising ovation.

The Garden was crawling with Hollywood and Broadway talent. (Lauren Bacall hailed me excitedly at one point and beckoned me over. I went. She said, her voice quivering with feeling, “Arthur, did you read Walter Lippmann’s column this morning?”) An act presenting the Republican platform in terms of doubletalk was particularly successful. At 10:30 the Governor came on. The excitement was by now overwhelming, and the ovation tremendous. The speech itself was unfortunately something of a flop so far as the immediate audience was concerned.

Afterward we went back to the Trees’ for a good and long party. Marie Harriman raked Joe Alsop fore-and-aft for his apostasy. Averell seemed cheerful; Wilson Wyatt was in good form; so too were the Sher-woods; Marietta, lovely as ever; etc.

November 1 [Final stop in Chicago]

We stayed at the Conrad Hilton in Chicago. I went in to see the Governor before the speech to say good-bye; he was going on to Springfield that night, and I was returning to Cambridge the next day to vote. He was in a good mood, just out of the shower, clad only in shorts, filled with a wry but definite confidence. “Of course, I’m going to win,” he said, “I knew it all the time. That is why I was reluctant to run. . . . I figure that I will get about 366 votes. I don’t see how I can lose.” (I should add parenthetically that Carl and Wilson were equally confident. I guessed 325 for the pool. The only man to seem really gloomy about things had been [Jake] Arvey when we left Chicago on the 21st.)

The Governor chatted on. “But I have been giving some thought,” he said, “to what I should say if I happen to lose. I thought that I would use the old story Abraham Lincoln used to tell—the one about the boy who stubbed his toe in the dark, who said that he was too old to cry but he couldn’t laugh because it hurt too much.”

I assured him he would not have to tell the story.

The Chicago speech was a fantastic success. The Governor even finished on time. The whole atmosphere was electric with confidence. Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart gave me a lift into town. We all went to a party given by Oscar Chapman at the Palmer House. (What a beautiful—and delightful—girl Lauren Bacall is!—even more attractive in the flesh than on the screen.)

November 3

I took the plane back to Cambridge [on Sunday]. I was still completely certain that we would win. I ran into Max Lerner when I changed planes in New York. He seemed unhappy and apprehensive—the first voice of pessimism I had encountered since Jake Arvey. When I got back to Cambridge that night, Marian was very worried about Massachusetts. Conversation the next day with several people persuaded me that we would probably lose Massachusetts. But I still considered this only a local phenomenon—McCarthyism, the Irish Catholic defection, etc.

Monday night, McCarthy erupted again. Then the Democrats had their concluding half hour, ending up with a rather sad little speech by Stevenson, cut off, as usual, before he had reached the climax. This was followed by an hour of unparalleled vulgarity and cynicism on behalf of Eisenhower and Nixon.

November 5

Tuesday night was sad. I knew as soon as I heard the results from Connecticut (about 8 P.M.) that we had lost. I received a flurry of phone calls in the course of the evening—from Tufts in Springfield, from Chet Kerr in New Haven, from Kay Graham and Evangeline Bruce in Washington, from Bill Wirtz and Ben Heineman in Springfield. Melancholy settled more heavily on all of us as the evening moved on. After [Paul] Fitzpatrick conceded New York and [Jake] Arvey Illinois, it was only a question of time before the Governor would speak.

November 26

Just a few words in conclusion. I suspect that I have given a more jaundiced picture of Stevenson than I actually feel. That is partly because at the beginning, one tends to overestimate Stevenson’s articulateness and see it as expression rather than as ejaculation. He verbalizes all the time and, like FDR, for a variety of reasons. The important thing should be, not what he says, but what he does. Every time things came to an issue of policy, he made the correct decision.

Also I now believe that on a number of things he was right and I was wrong. For example, I came very much to overestimate (as did Carl and Wilson also) the power of the prosperity/depression issue. It seems clear now that this issue appealed only to those who had personal memories of the Great Depression—which meant, on the whole, people in their forties and older. This issue meant very little to younger people, for whom Social Security and collective bargaining and economic opportunity were as secure and unalterable parts of the landscape as the trees and bushes. Adlai was right in saying that we should not run against Hoover. We were wrong in insisting that he should—at least, to the extent that we relied on it. One consequence was to weaken our appeal to the young.

Still, one consolation about being beaten 56 to 0 is that there is no point in wondering whether you would have done better if you had had a different left tackle—or a different quarterback. We made mistakes, all right, but none of them would have altered the outcome if done differently.

What we confronted this time was an upsurge of natural forces. Our number was up—and very little we could have done would have altered the outcome. But we did lay down a clear record. And the Governor did establish himself as a great national leader—gallant and honorable and dedicated. In retrospect, he seems to me more than ever the voice of the liberal future—the one creative hope in our politics. I shall always be proud to have served him in this campaign.

December 29

I saw the President today at 9:45. As I went in, I marvelled once again at the ease and informality of the American system. Dave Lloyd took me across the street from his office at Old State, past a couple of doors, and there I was in the outer office; then, two seconds later, I was in with the President.

Harry S. Truman was very cheerful, scrubbed and natty. He talked most of the time in a generally philosophical mood about the beating he had been taking from the press and about his confidence that history would vindicate him and his administration. When I came in, he quoted a set of figures on the national income, gross national product, employment, etc., and said, “Well, this is the ruined and collapsing state in which I am leaving the country.”

He was much concerned about the state of civil liberties. He said that he had feared post-war hysteria—it had always come after other wars, the Citizen Genet episode, and the KKK after the Civil War and the Palmer raids after the First World War—but that he had hoped he might be able to avoid it this time.

He felt that one of the great lies was the current attack on politicians. He feels that, as soon as he learned of any wrongdoing in his administration, he moved immediately to remedy it. “The professional politician,” he said, “is the straightest-shooting man in the country. I don’t mean the city machine type; but the man who makes a career of elective politics. The biggest crooks in the country are the businessmen. You know,” he continued, with feeling, “they’ll do anything—absolutely anything—for a dollar.”

I said that I thought that the Republicans through smear and slander would try to put the Democratic party out of business in the next four years. He smiled and said, “Well, they may try, but they won’t succeed. The Democratic party was here before any of them were, and it will be around long after they have been forgotten.”

He described his attempt to impress Eisenhower with the magnitude and gravity of the presidential job. “I called in [Dean] Acheson and [Robert] Lovett and [John] Snyder and Harriman and had them all brief him. He just sat there, his face cold and hard.” I asked whether he thought Eisenhower had gotten the point. HST shook his head and said, “No, I don’t think he got it.” What had happened to Eisenhower? did we all in the past just miscalculate the kind of man he was? HST said, “Yes, I guess that’s what we did.”

He spoke affably of Stevenson except to say that he was oversuspicious of the professional politicians.

I noticed that he still speaks of FDR as “the President.” He made several references to “the coalition of reactionary Republicans and anti–civil rights Democrats.”

September 12–14Democratic Party conference

I arrived in Chicago Saturday evening, September 12. After registering at the Congress, I went over to the Conrad Hilton and located some newspapermen. One of them gave me the number of AES’s suite. I phoned up, got Bill Blair and then went up. Adlai was there, having just returned from dinner with HST. He said that they had had a long talk together, and that HST had kept urging him to take over the active leadership of the party. AES evidently kept protesting his lack of qualifications; HST finally said, “Well, if a knucklehead like me can be a successful President, I guess you can do it all right.” HST made it clear that he was altogether in Adlai’s corner.

March 8[Boston]

President Truman came to town today to address a fund-raising lunch for the Truman Library. I had fifteen minutes to talk with him in the morning in his suite at the Sheraton-Plaza.

We talked considerably about McCarthy. He then began to muse about the incidence of periods of hysteria in American history. He told me (as he has before) that he had completed a “monograph” on this subject. As he figures it, the periodicity is about 8–10 years: thus, from the Alien and Sedition Acts to the trial of Aaron Burr; the Know-Nothing and anti-abolitionist sentiment of the fifties; Reconstruction through the election of 1876; from A. Mitchell Palmer to the campaign of 1928. So he guesses that it will take McCarthyism 8–10 years to burn itself out—which means anywhere from 1956 to 1960 before it is over. But he affirmed, both touchingly and impressively, his faith in the decency of the American people and their capacity to recover from these binges of fear and panic.

HST looked very well—trim, natty and cheerful as usual.

September 10 Libertyville, Illinois

Adlai met me at the station. He looked fine, and was as warm and easy as ever. He was delighted at Averell’s fortune in New York, while at the same time somewhat baffled over the political calculations involved, and quite respectful and even admiring about Franklin [Roosevelt Jr.]. He is optimistic about Humphrey and [Guy] Gillette.

He outlined his position in the following terms. He will not seek the nomination in ’56. He definitely will not enter primaries. If he is drafted, he will accept; but realistically he concedes that he will not be drafted twice. What he would really like to do in 1956 is to run for Governor of Illinois, or be Secretary of State. In the meantime, he does not want to be constrained by the Democratic party line; he would like to feel free to speak out his conscience as he sees it; and he thinks that this role would not only suit him better but would, in the long run, be smarter politics. “My present position,” he said, “is morally repugnant, emotionally unbearable and intellectually inconsistent.”

October 16[Cambridge]

Cold, rainy afternoon. AES [Adlai E. Stevenson] arrived about 2:30; around 4:15 went to the MacLeishes’; left about 5:30.

1. AES seemed philosophical about HST [Harry S. Truman]. Could not understand why HST should consider him superior to politicians, in view of the fact that he was the third generation of a family of fairly successful politicians; but presumes that HST does not consider him sufficiently an orthodox Fair Dealer and does not like his campaigning style.

His last face-to-face talk with HST was in Chicago in July. At that point HST reiterated his support and strongly advised AES to announce on Labor Day. AES then told him that he could not do that, that he felt he had no claim on the nomination, that he could only announce after there was some display of sentiment for him in the party.

Just before HST came East, AES called him to ask whether he was going through Chicago. HST replied that he was going through St. Louis this time. AES commented that he was worried about the Harriman problem; hoped that nothing would happen which might divide the party and weaken its chances in the election. HST: “Don’t worry about that. That’s why I’m going to Albany. I want to fix things up.” AES’s comment: “He fixed things up all right.”

Since Albany HST has told both Acheson and [Tom] Finletter that AES remains his number one choice. AES seems to doubt this, though I commented that I now believed that HST was just giving WAH [W. Averell Harriman] a run for his money and perhaps hoping to stimulate AES into a more militant stance.

2. On WAH: AES says that he is not much worried about the political effect of Averell’s candidacy, but is troubled and a bit hurt by the manner of it. He now thinks that WAH planned this from the start and deliberately deceived him about it. He is uncertain what he should do about it; is disinclined to make an open fight at this point. Obviously the Harriman problem concerns him more than anything else at this moment.

3. On [Estes] Kefauver: he spoke with admiration of EK’s well-organized campaign—the postcards; telegrams; the letter of congratulations from Moscow received by a Wisconsin Democrat on the birth of a child; etc. But he also rather fears that EK will try to strike a bargain for the vice presidency. While AES admires his legislative record, he feels that EK would be hopeless as Vice President; that he could not effectively serve as a liaison between the White House and the Hill, because he is so hated on the Hill. Apparently Johnson and Rayburn emphasized this to AES, saying that EK was the most-hated man to serve in Congress for many years.