Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

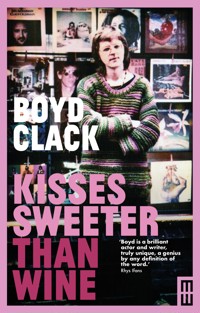

Kisses Sweeter Than Wine is a brutally honest and completely absorbing literary memoir from a man who has emerged as one of Wales's major cultural figures. Boyd Clack is a man of many talents: a writer, actor, singer, musician, enthusiast and with this first book picks apart a challenging upbringing in Tonyrefail, his wanderings to Australia, Amsterdam and London, his experimentation as a young man with drink and drugs and love. This is Boyd's story, told with an honesty and perception and skill that will absorb anyone interested in what it was to be young and Welsh – and are now older and maybe a little wiser.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 582

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Boyd Clack is an actor, writer, and singer/songwriter from Tonyrefail in the south Wales Valleys. He is perhaps best known as the creator, writer and leading actor of the many series of classic BBC sitcom’s Bafta winning Satellite City and High Hopes. He has also had an extensive career on stage, film, and TV including National Theatres (Canada, England, Wales); Twin Town, Under Milk Wood (film) and recently Keeping Faith (TV). Boyd is Patron of the New Horizons – Mental Health charity and, together with his partner, actress and scriptwriter Kirsten Jones, joint Patron of the Royal Commonwealth Society of Wales, Cardiff Mini Film Festival and Greyhound Rescue Wales.

Parthian, Cardigan SA43 1ED

www.parthianbooks.com

First published in 2010

This edition published in 2020

© Boyd Clack 2010

ISBN: 978-1-913640-09-5 print

ISBN: 978-1-913640-12-5 ebook

Cover design: www.theundercard.com

Edited by Penny Thomas

Typeset by Elaine Sharples

Printed and bound by 4edge

Published with the financial support of the Books Council of Wales

The Modern Wales series receives support from the Rhys Davies Trust

cataloguing record for this book is available from the British Library.

For my darling Kirsten

THE CLACKS

My father, George Windsor Clack, was born in Barry in south Wales on 31 October 1909. He died of leukaemia in Vancouver, Canada in 1954 when I was three years old. I’ve met very few relatives from his side of the family. There was Auntie Muriel, who lived in a prefab on the prefab site opposite the grammar school in Tonyrefail in the Valleys where I grew up. I don’t remember her well; in fact I can’t remember what she looked like at all. I have no physical image of her whatsoever but I do remember an aura of warmth and generosity. Her husband, Uncle... I can’t even remember his name (sounds like I’m making it up doesn’t it?)... was one of those people you never see. He was always in bed or out walking or in the shed. Sometimes you’d go into a room and there would be traces of his pipe smoke still hanging in the air or a half-eaten meal on the table. He was ill. It was probably silicosis or cancer or maybe the result of some war injury. He was very ill for a long time then he died. I’ve no doubt he was a nice bloke. I used to visit them quite often at one time but it stopped for some reason. They didn’t take me any more. My mother probably fell out with them. My mother fell out with everyone eventually. The prefab was like a toy house. It was an exciting place to visit. They had a dog I think.

I have a cousin Barry Lewis from the same side of the family. He was a policeman in the Tonyrefail area when I was a teenager in the late sixties. I was a Bohemian dreamer and he was a copper. I saw him at my mother’s funeral service. I have never communicated with him beyond idle chat but he has always seemed a decent enough fellow to me. There was another cousin called Royston James and his family. Royston was known as Squack. We worked together in the Treffano shoe factory in 1971, the year I emigrated to Australia. Squack was a trendy young man. He dressed fashionably and had an eye for the ladies. I remember he combed his hair a lot. ‘Ride a White Swan’ was high in the charts. He was a young guy bopping about seeking happiness. I liked him. Haven’t seen him in years but I liked him.

I was driving through Trebanog with my brother Blaine and we turned off the main road and stopped outside a terraced house. The people there were Clacks. They had a gorgeous, sexy daughter about my age, a bit younger maybe. I’d’ve been eighteen. We had a cup of tea then left and I never saw or heard from any of them ever again. I only remember the incident because of the daughter. She was a Doll. There was another Royston too. I think he was from Auntie Mu’s husband’s side of the family. The family name Lewis must be from them. There was Barry whom I’ve already mentioned and there was a teacher when I was in the grammar school named Miss Lewis, who was related in some way. She taught economics. She was posh by my standards and dressed very smartly. It was rumoured amongst us students that she was having a secret love affair with the physics teacher Ambrose Hunt, a handsome man with a strong, sad aquiline face and short lank grey hair. He looked like an SS officer. He looked like Reinhardt Heydrich, the deputy head of the SS, in fact. Anyway, however he looked it did the trick with Miss Lewis. It was said that she and Ambrose used to drive up to a well-known lovers’ meeting point in a forest on a nearby mountainside to be alone and on one such outing they were involved in a serious accident. Ambrose got out of it unscathed but Miss Lewis suffered some scarring, but it didn’t stop her being beautiful. I liked her a lot but I don’t think she ever thought about me.

There was someone else, another Clack. He lived in a strange old battered house just off the Tonyrefail to Talbot Green road. He was a rag-and-bone man, virtually a gypsy if my memory serves me right. The front yard of his house was piled with rubbish, metal objects, old vehicles and so forth. I think he actually lived in an old caravan outside the house. I was taken to see him two or three times. He seemed eccentric to me to say the least. I think he had a daughter living there too but I don’t remember her at all. There are other people who I think are related to me in some way but I’m not sure how. Maybe they were from my father’s side of the family. I don’t know. The name Uncle Eddie rings a bell. Maybe he was Auntie Mu’s husband. The fact is that I have had next to nothing to do with the Clack side of my family. This was not by choice, but my father’s early death resulted in an unintentional alienation. I’m sorry about this. I would like us to have been closer.

The Clacks had come to Wales from Crewe in the nineteenth century. They’d been railway workers. My grandfather’s name was David and my grandmother’s was Mabel. I met neither of them. My father emigrated to Canada through a Salvation Army scheme in 1928. He sailed from Southampton on the Empress of Australia. He worked in an apple orchard for the first few years and was thought well of by his employers. I have a photograph from this time and I am pleased to say I see something of myself in him. I believe he went on to work as both a gold miner and a lumberjack. I don’t really know anything else about his life in Canada until he joined the Canadian Army at the outbreak of the Second World War and after initial training in Iceland ended up on leave in Tonyrefail sometime in 1942. My Auntie Mary, Naine as she was known, my mother’s sister who brought me up, spoke of him with fondness. He was a lovely man, very good looking, quiet but humorous. This was high praise from Naine who, like my mother, never had a good word to say about anyone. Uncle Will, Ool as I called him, Naine’s husband and my surrogate father, talked to me about him once or twice, not often, but when he did he spoke in an affectionate way too. He really liked him. My father smoked a pipe and was a very good darts player. From the few photographs I’ve seen he looks a nice chap. He had sad, weary-looking eyes. I’ve always had the idea that my father just bummed around Canada doing an assortment of romantic jobs like a prototype beat poet. I have an image of him being a quiet, intense man, a sort of Shane figure. I think he may have been religious. I seem to remember hearing that he’d become a lay preacher towards the end of his life. This suggests that he may never have been the romantic adventurer I imagined him to be. Maybe he was a philosophical man. Maybe, just as fathers are said to want their sons to be like they wish they had been when they grow up, I have imposed my romanticised image of myself onto him, my dead father whom I never knew. The thing I can say for definite is that it’s possible to love someone you never really knew and I loved my father.

THE GRIFFITHS

My mother, Ellen Elizabeth Griffiths, was born in Tonyrefail sometime towards the end of the First World War. The Griffiths family lived in 64 Pretoria Road, a terraced street that was back to back with The Avenue where I was brought up. The house was on the far side of Pretoria Road, the ‘Red Cow’ side, the Glyn Mountain side. The Griffithses were a rum bunch indeed. I believe they were quite well off at one time, owning a large amount of land around Gwaun Cae Gurwen in west Wales. The men in the family were a bunch of no-good, drunken, gambling wasters and lost all the family’s fortune playing cards. There was an alleged curse laid on the family at that time over some civil dispute. It said that from that moment on the male offspring were damned to ill health, madness and misfortune. It seems to have worked because, with few exceptions, all the Griffiths men that I met seemed to be broken, clownish losers. Anyway, in those days the family was called the Caemelyns. How it changed from that to Griffiths I don’t know, but the curse was not ‘The Curse of the Griffiths’ but ‘The Curse of the Caemelyns’, which sounds much more mysterious and satisfying to me.

The patriarch of the family at the time my tale begins was my grandfather, Daniel Griffiths, or Dan the Yank, as he was universally known. I’ve seen an old black and white sepia-tinted photograph of him. He was a thin-faced man with a well-developed moustache. There was no trace of a smile on his lips. His wife, whose name I do not know, stands behind him rigidly in the photograph. They were first cousins. She died of cancer after a long illness. My mother once told me that she had worked herself to death looking after their fourteen children. Either way she died young. Cancer has played a big part in the Griffiths’ family history. Indeed, cancer had an almost religious role in Welsh Valleys life in those days. It was the Angel of Death itself, judgmental and merciless. Naine was obsessed with it. She’d tell me about a relative she’d nursed with cancer of the throat. She said he’d push his hand into his mouth and try to tear the growths out with his fingernails. Her face would light up when she talked about it.

Dan was called the Yank because on several occasions he’d gone to live in America. He’d just leave his wife and children to fend for themselves and go. He’d desert them.

It is said that he lived with the Shawnee Indians for a while on their reservation. He toured with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. I believe he even toured the UK with them at one time. My stepbrother Brian (actually my cousin) remembers him well from when he was a boy and liked him very much. He told Brian that when on the road with the Show he would often share a room and a bed with Buffalo Bill himself. He said that Bill would take a six gun from its holster on the bed post and threaten to shoot Dan’s big toe off. Dan, I forgot to mention, was a drunk, and I’ve no doubt Bill was too. After finishing with the Wild West Show, Dan moved to New York, where he opened a restaurant in partnership with Jack Sharkey, the ex-world heavyweight boxing champion. I am unaware of how this venture turned out. There are quite a few Griffiths still about over the pond. Indeed, Uncle Jake became Mayor of Chicago on more than one occasion. At some time it appears that Dan was the owner of The Globe Cinema in Gilfach Goch, a mile or so from Tonyrefail. He also owned a pony and trap, which was the very one used in the sixties BBC serialisation of How Green Was my Valley, which was filmed in the area.

As far as I can tell Dan the Yank was a right bastard. Naine told me that he used to beat her and the other children on the back with a pickaxe handle, which he kept specifically for the purpose. The other Griffithses I knew were Naine, my mother, Uncle Ike, Uncle John, Uncle Danny and Uncle Glyn. That’s six. There were twins too, I think. In fact I seem to remember hearing that my mother was a twin and that the sister died in childhood. I believe her name was Maude. Maybe I’ve got this wrong. Maybe there were no twins. Uncle Ike was a chronic alcoholic. It is said he was dishonourably discharged from the army after less than a day, when conscripted in the Second World War. He arrived at the training camp drunk and they couldn’t wake him up so they threw him back. I have even heard it said that he was the first man to be dishonourably discharged from the British Army during the entire conflict. I knew Uncle Ike as I was growing up and the story rings true.

Ike lived in digs at 77 Meyler Street in Tonyrefail for years. He was the only lodger and the owner, a kind woman, took care of him. This was no easy task as he was a genuine staggering, trouser-soiling, vomiting type alcoholic; not a romantic literate drunk. She had to wash him and put him to bed on numerous occasions. She was a Christian. Ike was a good gardener. He used to make a few extra bob at it. He did the doctor’s garden for years, Doctor Monroe.

Ike dressed quite well. He was given second-hand clothes, good clothes, by the middle-class people he gardened for, and his landlady made sure he wore them clean and laundered. He had some lovely overcoats and ties and scarves and cravats. At first he could control his drinking to the degree that he could attend some social functions relatively sober, and this was admired in him, it being no easy thing for an alcoholic to do. His life fell apart when his landlady died and he started sleeping in the public toilets and gutters. He shared a battered old caravan parked on a patch of waste ground near the Non Pol club with another notorious alcoholic named Tommy Bright for a year or so. Tommy was barely alive. He couldn’t even stand up straight. He had the alkie’s nose too, broken repeatedly in fights with drunken, violent youths. Tommy couldn’t fight but he could be hit and there was little mercy about in those days where I come from.

Some twenty-odd years ago Uncle Ike was put in an old folks’ home in the Tonypandy area. I visited him there once or twice. He got old there and he got stone deaf there too. He was still an alcoholic but he managed not to be thrown out of the home somehow and became a fixture. When I was a boy he used to come to the house quite regularly. He behaved in front of Naine, his big sister, and would often pass for virtually normal on these visits... at first. He was no intellectual. I don’t think I ever heard him say a lucid word. Indeed, much of what he said was virtually unintelligible. This was because, despite never having been further than Oswestry in his life, he had somehow developed a flamboyant American accent. My brother Brian claims that Ike was once saved from a severe beating at the hands of some English Red Caps by the intervention of a couple of American soldiers, and that was enough for him. He took to screaming out insults about Wales and the Welsh people in the streets at the top of his voice when drunk and this led to regular visits to the casualty department of Porth Hospital. A bus driver beat him almost to death with his ticket machine once when he refused to get off a late-night bus after soiling it. He was a no-hoper.

One of Uncle Ike’s regular appointments was Christmas dinner at our house. We’d be at the table-laying stage and he’d arrive, passing the window looking immaculate in a suit, normally double breasted, an overcoat and a hat. We’d dine together at the table and Ike would limit himself to a single glass of beer with the meal. This would be his first drink of the day and he’d sit by the fire for an hour or so afterwards before going off to do his round of the pubs. He’d get plastered. No, the pubs wouldn’t have been open, not on Christmas day in the 1950s. Where did he go then? Yes, he had his rounds to make! Other people he visited. I wonder who the hell they were.

Anyway, as the years passed his control disintegrated and he began turning up plastered on Christmas day. His arrival became predictable and we would fear it. He’d stand outside the window shadow boxing and pulling grotesque faces like Popeye the Sailor Man. He had an entire repertoire of them, the old alcoholic shuffle. He’d normally wait for Naine to be looking the other way and when she’d finally turn and catch him she’d look really disappointed and say ‘My God. Look at the clown!’ then rush out and drag him indoors. Once inside he’d sit on the armchair by the fire when Naine was in the kitchen cooking and he’d sing unintelligible songs in an American accent and pull faces and make signs at me as if we were in secret cahoots about something. He was as crazy as a coot, it has to be said. When I was old enough to get pocket money he used to take it off me while making signals not to tell anyone. What did I get out of this secret alliance? Sweet FA...!

When the Griffiths boys were young men in the thirties, they, like Dan the Yank himself, used to fight other blokes for money up on the Glyn Mountain. Crowds would gather and bets would be laid. My Uncle John was a particularly hard man even into old age. He was crackers too but that’s another story. I’ll tell you about him later.

Anyway, drunk from a morning on the beer one Sunday afternoon Dan and Ike, father and son, were stripped to the waist sparring in the back garden of Pretoria Road. They were screaming and shouting, swearing no doubt, and finally the woman who lived next door stuck her head out of an upstairs window and asked them if they wouldn’t mind keeping the noise down because her husband was on night shift and couldn’t get to sleep. Apparently Dan the Yank shouted back ‘Send him down here. Ike will put him to sleep!’ Then there was an Alsatian dog in a house a few doors down the street, which used to bark at Dan as he passed by. Dan told the owners to sort the dog out or he’d do it for them. They didn’t, so he went into their garden with a shotgun one afternoon and blew the unfortunate creature’s head off.

Ike would be taken over by a nightmarish mutated version of his father when drunk. He’d jump up from where he’d be sitting, strike up a fighting pose and then say something ridiculous in his American accent. Something like ‘Whooah there Buddy. I’m from New York. I’m the Yank. The Yankee boy. Whooah!’ Then he’d tip his hat over one eye and shadow box till he fell over. Like I say, he was crazy, but my mother and Naine loved him. I got the impression that he had been a man of integrity at one time and that some people still held him in regard. They still saw the ghost of that integrity within him, they saw a good soul buried there and maybe they were right. I never saw it myself. I was afraid of him when I was small. Then when I got older he was too far gone for me to relate to him. Indeed he was too far gone for anyone to relate to him by then except for Tommy Bright. Their caravan was burned out by some local thugs. It was torched for a laugh. Maybe Tommy was still in there at the time. If he was then he escaped. I don’t know what became of him. Uncle Ike died in the old folks’ home when I was living away.

When I was a child our dog Mickey was kicked almost to death by a passing motorcyclist and Uncle Ike took him to the vet in Porth to be put down. I remember watching the bus going up the hill with Ike holding Mickey, waving goodbye from a window. I asked Naine where they were going and she told me that Uncle Ike was taking Mickey to Heaven. I still relate that image to going to Heaven; that you go there with Uncle Ike on a bus up Collenna hill. I can’t think too clearly about Uncle Ike now, to be honest. I never heard of a woman in his life ever. There was no history of love. No broken heart to cling to, not that I knew of anyway.

Uncle John looked mixed-race. It was unmissable but I never heard anything, no hint of scandal that might explain it. He was hyperactive. He spent his entire adult life working in a watch factory in London. He lived in Kilburn with his wife Edna, a lovely, kind woman. I stayed with them once. I must’ve been five or six years old. I remember lying in a cot in their room, at the foot of their bed, late one night trying to sleep but too frightened to do so. As I lay there in the darkness I heard the sound of a single drum being beaten slowly and rhythmically somewhere outside, somewhere in the hollow, deserted streets of Kilburn. I remember thinking that this lone drummer was at the head of a silent mob marching towards the house I was staying in. I imagined them assembling outside in the darkness, gathered in the street outside the curtained bedroom window. I was paralysed with fear. It was the beating of my heart. Auntie Edna died not long after. She’d been ill for a long time. They came to stay with us in Tonyrefail a few months before. Auntie Edna had to stop off at the ladies’ toilet on their way to catch the bus back to Cardiff to go back home because she was feeling unwell. We waited outside for a quarter of an hour. I don’t know what was wrong with her but I was told that her insides had filled up with pearls and that is what killed her.

They had a daughter, Janet, who was a few years older than me. She used to come to stay with us sometimes during the school holidays. She’d stay for weeks, months even. Janet was a tall, gangly, severe-looking girl with short black hair and horn-rimmed glasses. She was as mad as her father. We used to play pretending to kiss in my bedroom. She attacked me with a carving knife, chased me from room to room. She ended up driving the knife into the kitchen door trying to get at me. Uncle John came into my room one night hysterical and stinking of booze, and gave me a good whacking across the arse with his leather belt. Apparently Janet had told him I’d done something or other. It hurt like Jesus. Uncle John was genuinely nuts. He was a grade-A banana. He could barely get words out such was his constant level of hysteria. He’d dribble and gasp till he’d have to sit down exhausted and mop his brow with a handkerchief. I don’t know whether I liked him or not because I never really had any idea what he was like. He was, if you recall, a very hard man. He’d been the outstanding hill fighter amongst the Griffiths boys and his reputation lived on. I was in Hayward’s fish and chip shop with him one evening and a group of local thugs entered, drunk and looking for trouble. The ringleader, a huge violent creature devoid of all human feeling or intellect, began pushing people around and Uncle John went for him. It ended up with the bully legging it like a man possessed, with a screaming, dribbling Uncle John hot on his heels. He chased the lad for over a mile.

My brother Brian’s then wife, Frances, used to take Janet and me to her place of work as a treat sometimes. She was the secretary to the manager at the Royal Sovereign Porcelain factory. We’d sit typing on machines or playing word games. Janet was very competitive. I never figured out why she hated me so much. She once gave me a coded message, ‘LILY’ it said. I had no idea what it meant so she told me to drop the first letter and that the other three were the initials of her message. ‘I L Y’ – I Love You! Well she had a funny bloody way of showing it. I last saw Janet when I was about ten years old. When she got married some ten years later she refused to have me at the wedding. Uncle John died soon after and I never heard from Janet again.

Uncle Danny went to Germany with the Civil Service after the war in some minor clerical capacity to help reestablish a civilian government, and when there became chummy with the upper-class types who were in charge of the operation. It seemed to have given him a home-counties accent and an air of superiority. He reinvented himself as posh in fact. When he returned to England he got work as some sort of apparatchik in Whitehall and became a personal friend of Jim Callaghan’s. He was white haired at a young age and had the most peculiar sneeze you ever heard. When you first heard him sneezing you thought he was kidding. It sounded like an expensive firework taking off. Anyway, along the way he’d married Auntie Rene. She was a goodlooking woman with pronounced lips. I liked her.

The last time I saw her and Uncle Danny was at Naine’s funeral. Uncle Danny seemed a silly man to me, a pathetic figure. Auntie Rene wasn’t silly though. She had an air about her. They had two children, my cousins: a daughter named Eurwen and a son, Tony. I never actually met Eurwen but she was always spoken of with affection by everyone I met who knew her and I have a soft spot for her on the basis of that and her lovely name, Eurwen Griffiths. The son Tony was a globetrotter. He was an adventurer. He was a high-ranking police officer in Kenya at the time of the Mau Mau uprisings: a brutally suppressed rebellion against colonial rule. At another time he was the editor of Kenya’s national daily newspaper and a topclass cricketer to boot. He was in fact the scorer of the quickest double century ever scored in Kenyan first class cricket. I remember seeing a newspaper article about it with a photograph of him executing a classic off-drive on his way to the record. He lived on a huge farm in Kenya with herds of wild animals and tribes of black servants. He, along with my cousin Trevor and my schoolmate Geoffrey Holtham, was the shining example that I was constantly urged to emulate when growing up. They’d say ‘Your cousin Tony wouldn’t be covered in shit’ or some such thing at every opportunity in order to belittle me.

I met him once. He came to Tonyrefail, to 10 The Avenue. He arrived in a huge Jeep, which he parked out the front of the house. This would’ve been about 1960. His wife was with him. I don’t remember her at all but he was an impressive figure, tall and athletic, very handsome in a rugged, English-officer way. He wore shorts, the first time I’d ever seen an adult in shorts, and talked to me, albeit briefly, in an adult fashion. He was what everyone had always said he was – a real gentleman. I was very taken with him. I recall him saying ‘I have never thought myself better than any man, Uncle Will... but I have never thought any man better than me.’ Where he, his family and Eurwen are now I have no idea. Eaten by lions maybe.

Uncle Glyn lived in Mountain Ash and we visited him occasionally when I was a child. He died after a long illness. He wasn’t like the others as far as I could tell. He was a quiet man; I think there was a bit of angel in him. Then there is Naine, my mother’s sister Mary, who brought me up, and Ellen Griffiths, my mother herself. I know little of their upbringing other than that it took place in an atmosphere of lovelessness and drunken brutality. Naine was the eldest sister and became like a mother to the others when their real mother was bedridden prior to her death. Naine would’ve been about twelve at the time. She worked like a slave for years to bring the others up, while my mother, according to contemporary reports, was a self-centred, lazy little bitch. Both grew up with disfigured characters. Neither could express affection. They hated everyone and everything. They hated each other. I don’t blame either of them now but I was a very unhappy child.

When Naine got old she lost most of her bitterness in a sort of second childhood. It was as if the flame had died. I loved her lots then. She’d tell me stories from when she was growing up. She’d act them out. Many was the time we’d end up waltzing around the living room imagining an orchestra playing ‘The Blue Danube’ behind us. We’d be back in the 1930s. We’d be in the Muni dancehall in Pontypridd. Naine used to go there once a week with her boyfriend Gethin, Friday nights. Gethin was a great dancer. His arms and legs were like dandelion stalks blowing in the wind. He was good looking too, well not ‘good’ looking, ‘nice’ looking, and he was always the perfect gentleman. One particular Friday night Dan the Yank forced Naine to take my mother to the dance with her and Gethin so that he and his friends could use the house to get drunk in. Naine had no choice. While waiting at the Ponty bus stop Gethin popped into a nearby shop and bought, amongst other things, a great big half-pound bar of Cadbury’s chocolate. It could have been a onepound bar, a huge bar of chocolate either way. It was a present for Naine. When they got to the Muni and found a table to sit at Naine took the bar of chocolate out of her handbag and broke all three of them off two squares each. They wolfed them down with relish. This wasn’t long after the great depression and people were poor. Chocolate was a treat. Gethin whisked Naine away to the dance floor moments later, where they danced wildly until exhausted. When they arrived back at the table the chocolate had gone, the empty wrapper was all that remained. When challenged my mother’s mouth was so full of chocolate that she could hardly be heard denying it was she who’d eaten it. She said it was someone else, a stranger. Lumps of chocolate dribbled from her mouth as she spoke. Caught red handed she still lied. It was a pattern she repeated for the rest of her life. Anyway, sometime in 1942 my mother, who was in the WRAF, found herself somewhere in Tonyrefail at the very same time and on the very same spot where my father George Wyndsor Clack, on leave from the Canadian Army and wearing a greatcoat with little polar bears sewn onto the sleeves to show he’d trained in Iceland, found himself. And they met.

THE HAPPY COUPLE

I don’t know anything about the circumstances of my mother and father’s meeting or from that point to the wedding. They got married in St David’s Church in Tonyrefail. There is a photograph. My father is in his uniform and my mother is in white. They are cutting the cake. This was at the reception back at the house, Dan the Yank’s house, I presume. My father and mother are holding the knife between them. They are smiling, the knife is held delicately, lovingly. The moment is captured perfectly. I haven’t seen the photograph in years. I believe my mother was with child, my sister Audrey. When I was young I was aware of the circumstances of my father’s death and I always assumed that my parents’ marriage was a love match, another romantic drama thrown up out of the turmoil of war. I imagined the ‘loving wife staying at home to care for her beloved husband as he slowly died’ scenario. I don’t know if this is true. My brother Blaine, who is older than me and remembers some of it first hand, has told me different, but I don’t know.

My father was in The Royal Regiment of Canada. He was one of those blokes you see running out of landing craft on foreign beaches being mown down by machine gun fire. Shortly after he got married his regiment was sent on what has now become known as The Dieppe Raid. I’ve read about it in military history books. The raid was a deliberate sacrifice of men for the purpose of assessing the German coastal defence capabilities in the area with an eye to the eventual D-Day invasion. German intelligence was aware that the raid was going to take place and British intelligence was aware that the Germans were expecting them. The landing beaches were heavily guarded. It was a slaughter, of course, but contrary to what one might expect it was not the ruthless British High Command who insisted on Canadian troops being in the vanguard of this suicidal attack but the Canadian military themselves who wanted to ‘blood’ their inexperienced forces in the realities of the European theatre of war. There were incredibly heavy casualties. My father survived the initial landing but was captured by German soldiers a mile or so inland after being given away by a French farmer. There was little sympathy for those captured and my father and a few thousand other prisoners were marched in chains right across France and Germany. There was a German directive to treat allied prisoners badly at the time in retaliation for the bad treatment of some German prisoners. My father was interned in one of the Stalag prison camps, Stalag Three I believe it was, and spent the remainder of the war there, about three years. These camps were not like the camps you see in war films. This was not the sanitised world of The Great Escape. Starvation and brutality were the order of the day. My father was in a hell of a mess when he was released, when he came home. I’ve got no idea how he dealt with it. Maybe his religious beliefs gave him strength. I saw a piece of newsreel film from that time on a television documentary once, Canadian soldiers undergoing a medical, and I was sure that one of them was my father.

As far as I am aware my mother gave birth to my sister Audrey in 1943 and then just hung about in Tonyrefail waiting for my father to return. Naine looked after Audrey no doubt, while my mother continued to gallivant. Naine never missed out on an opportunity to disparage my mother and vice versa. The truth is hard to gauge in such circumstances. My father was repatriated in 1945 and returned to Pretoria Road in Tonyrefail, where my mother should have been waiting for him. There was a mix up, however. She went to Cardiff on the bus to meet him off the train as a surprise, but my father, not knowing this, had arrived in Cardiff early and caught the bus to Ton by himself, so they unwittingly passed each other halfway. Naine was in the living room in Pretoria Road on her own. She was poking the fire when the front door creaked open slowly; this was when you could leave your doors unlocked. At first it seemed there was nobody there but then after a few moments a soldier’s cap was thrown in onto the carpet, a Canadian soldier’s cap. Then my father came in. Naine said she nearly fainted when she saw him. His face was like a bare skull with a thin layer of skin stretched over it. All his teeth had fallen out due to malnutrition. He weighed less than seven stone. He’d thrown his hat into the room before entering so as not to frighten anyone by his sudden appearance, to warn them. Naine kissed him and sat him down, she really liked him you must remember, and as they talked she boiled him two eggs in a saucepan on the open fire. Eggs were rare then due to rationing and they’d been kept specially. She told me that she was crying her eyes out but she was facing away and kept the tears out of her voice so as not to upset him, that it was heartbreaking to see such a fine man reduced to this. She said that her tears poured down her face and fell into the water with the boiling eggs. I feel really sorry for my father. He had a rough deal. My mother arrived back home eventually and they were reunited.

The next thing I am aware of is that my father, my mother and Audrey went back to Canada to live. Why or how I don’t know, though Canada must’ve seemed an attractive option in the post-war period when Britain was and would remain in a prolonged state of austerity. I imagine that the Canadian Veterans’ Association would have seen to many of the practicalities. So in 1946 the Clack family went to live in Vancouver, British Columbia. My knowledge of what happened after that is very sketchy. What I know is that my father was in and out of hospitals regularly from then till his death from leukaemia in 1954. My father’s death was long and drawn out. It was caused by the privations and ill treatment he suffered at the hands of his German captors. A close friend of mine died of leukaemia and there was a spiritual tranquillity to him. Maybe it was the same for my father. I like to think so. In 1947 they had another child, my brother Blaine. He was named after the geographical boundary between Canada and America, the Blaine Line. I don’t know anything about his early life in Canada except that on the seventh of March 1951 he got a baby brother, me!

THE LAND OF MY FATHER

I was an easy birth. I arrived in the middle of the night. Blaine and Audrey had been difficult births. My mother was worried about me but luckily I was a piece of cake. This is hearsay you understand. I don’t remember a thing about it. I was christened Boyd Daniel Clack, Boyd after a local doctor, and Daniel after the Yank of that name. There is a story that my father called into a local bar on his way to register my name and got plastered on whisky and this resulted in him getting my first two names mixed up. Apparently I was meant to be named Daniel Boyd Clack. Someone once commented that I am fortunate my name isn’t Johnnie Walker Clack.

We lived in a town called Courtenay on Vancouver Island. Our house was made of wood and painted white. I really don’t remember anything specific about my early days in Canada. I used to think I remembered sitting on a wooden chair outside a garden shed and my father being inside. There is a photograph somewhere of me sitting there and I think I made the bit about my father up. There are some isolated images, an unsteady footbridge high above a river, a party outside near some sort of barn-like building, a commotion in the back garden late at night. I think there was a cougar in a tree and people threw buckets of water up at it to make it go away. I remember banging my face and crying, I fell out of my high chair, I’ve still got scars on my chin as a result. They tell me I climbed into the back seat of a visiting doctor’s car and fell asleep and he drove hundreds of miles before I was discovered. The predominant feeling I have from this time was being aware that my father was dying. He spent long periods in hospital. My brother Blaine tells me that my mother used to doll herself up and go out a lot. I really don’t know what happened in those years before my father’s death. I have no positive memories of them. He died in 1954 and, feeling isolated and lost no doubt, my mother decided to return us all to Wales.

We travelled across the Rocky Mountains by train. I had a bunk bed. I couldn’t sleep one night so I got out of bed and went for a walk along the rattling corridors in my pyjamas. It was dark and I got frightened. A guard found me and gave me a glass of warm milk and a sandwich in his little office before taking me back to the sleeping car. There was a wonderful taste to the sandwich, a taste that lingered in my mind for years, invoking intense memories of the time, like Proust’s Madeleine. I didn’t discover what it was until a long time later. The sea journey across the Atlantic was a blur. I remember being bought a little sailor rag doll in the shop and throwing it over the side of the ship into the sea. We arrived in Liverpool and I had a ride on a red rocket ship. It was lit with multicoloured fairy lights. We travelled down from Liverpool to Cardiff by train. Naine was with us. She must’ve met us in Liverpool. We got to Cardiff in wintry blackness. Ool, my Uncle Will, was there to meet us. I remember him walking around a corner by a sweet stall, wearing a thick overcoat. It was very cold. We were taken back to Ool and Naine’s house, 10 The Avenue, Tonyrefail, which backed on to Pretoria Road, and we all fell asleep.

I have already told you about Naine, how she and my mother, though sisters, hated one another. I learned later that there had been some incident in which my mother had tried to sow disharmony in Naine and Ool’s marriage years before. Naine was eaten up with bitterness. Why the hell my mother chose to run to Naine in her hour of need I’ll never know. Neither did my mother apparently, since she spent the rest of her entire life cursing her decision to leave Canada, though since she cursed everything else it may have been just habit. I suppose it’s a case of blood being thicker than water. There was an initial period when things were all right between them when we first returned. My father’s recent death must’ve kept the lid on the box of fireworks for a time, but it didn’t last long.

Another important player in my tale is Ool, William John Ball. I called him Ool because that’s how Will came out in my little-boy Canadian accent, same with Naine. The names stuck. Ool was one of thirteen children. He’d been born in Ynysybwl in about 1910. His family was desperately poor and when he was a little boy he went to live with another family nearby, the Shepherds. He had little education and went to work with the horses on nearby Mynachdy farm when he was ten. He had a younger brother who drowned swimming in a local pond at about the same time. He went on from there to work in the pits when he was fourteen. I don’t know anything that happened after that until, one day years later, he was cycling along Pretoria Road and a maiden scrubbing her front doorstep caught his eye. The story goes that he began passing that way regularly after that until one day, suffering a convenient puncture, he stopped and asked her for a bowl of water so he could fix it. They got married some time later. When they got home after the wedding ceremony they had fish and chips from the fish shop as a wedding dinner and were left with six shillings. That was their total wealth. I found out years later that Ool had been married before; he’d had a childhood sweetheart who’d died of cancer and he’d married her on her deathbed.

It seems that from the beginning there was a perceived mismatch here. The Griffithses for some inconceivable reason considered themselves to be a cut above other working-class families. Why this should be is anyone’s guess. It may be because of the land they had owned and lost in west Wales years before or because they had relatives in America, who knows? Ool’s family on the other hand had no such pretensions. A relative told me that they were of gypsy stock and it makes sense. Ool was a short, dark man with a distinct Romany nose and his brothers were similar. Whatever the reason, Naine always treated him as an inferior.

I have met quite a few of the Ball family because they lived near us. There was Uncle Rhys, a morose man who was very close to Ool. He lived in The Avenue too with his wife Auntie Rene, a big smiling woman worn down by hard work as most housewives were in those days. They had a son, Elvert, who also lived in The Avenue. He had his toes removed after getting gangrene from a minor operation. I don’t remember much about him. There was Uncle Arthur, who had a nasty scar on his lower lip; he died of cancer. I liked him a lot. Then there was Auntie Cassie who lived in Llanharry. We visited her there a couple of times. Going that far was quite an adventure.

Uncle Les was a nice bloke. He lived on the housing estate behind the primary school. He had two sons, Trevor and David, and a daughter, Peggy. We didn’t hang about together much but they were good lads both of them and Peggy was, and is, simply an angel. All of Ool’s brothers and sisters are gone now, as indeed is he, except for Uncle Rhys, who still ambles up and down to the Red Cow most afternoons. Last time I saw him he was still sad. I believe he was on medication for depression and anxiety.

When I was a boy Uncle Ivor was my favourite uncle. He lived in the prefabs near to my Auntie Mu. He had a wife, Mavis, and a daughter, Barbara. Barbara was five years older than me and used to take me to the pictures on Monday evenings. She’d wait for me after school and we’d go back to the prefab and have tea and talk and play before hitting the Savoy on Ton Square. In later life, after Uncle Ivor died, Barbara and her mother both developed schizophrenia and spent long periods in mental hospitals. I never saw Barbara again but Auntie Mavis would turn up at the house once in a while. She’d ring the front door bell, and come in for a cup of tea and a cigarette. She was a short, plump woman and wore a mask of badly applied, cheap, gaudily coloured make-up. Her lips were as red as an electric fire. She dressed in the clumsy, unattractive way that mentally ill people often do. She drenched herself in cheap-smelling perfume and wore a profusion of childishly cheap costume jewelry, the kind you get in lucky bags. Nothing seemed quite right. She was a dear soul. Both she and Barbara are dead now.

Ool’s mother, Granny Ball, also lived in The Avenue. She was an old woman even then and in retrospect distinctly Romany in appearance. Her husband, Ool’s father, was dead. He was a dapper man by all accounts and used to go for regular long walks every Sunday. He’d take a cloth with bread and cheese wrapped in it, tied in a bundle on the end of a stick, which he rested over his shoulder in the traditional image of a tramp. My brother Brian told me once that when he was a teenager in grammar school he used to sit with the by-then-aged and bedridden Dan the Yank in his bedroom doing his homework and chatting. On one such evening the doctor arrived and told Brian to go downstairs, which he did. Ten minutes later the doctor came down to the living room and announced to the family that everything was all right and that Dan would be dead by morning, which he was. The family thanked the doctor profusely and they shared a cup of tea before he left. The very same thing occurred less than a year later in the case of Granddad Ball. I contemplated this on-the-face-of-it shocking revelation but came to realise that this made sense at that time. Families were desperately poor, there were no social services as there are now, and an inactive, non-productive mouth to feed was a great burden. Seventy was a very advanced age then and palliative medicine wasn’t so readily available. Indeed the National Health Service had only recently come into being and people’s memories of the hardship of nursing a person through long-term fatal illness were raw. It struck me that this mutually agreeable euthanasia was obviously common practice. In this post-Harold Shipman age such thoughts are a little frightening but I’ve no doubt that doctors in working-class communities in those days put an end to probably thousands of such lives in their careers. I’m not equating these doctors with Shipman here, I must point out. These doctors were acting in a vastly different context; Shipman was simply a murderer, these doctors acted with at least the tacit approval of the families involved and, I wouldn’t be surprised, with the approval of the invalids themselves in many if not most cases. It is nonetheless fascinating. Anyway, Granny Ball lived on in the marital home on her own for many years after her husband’s death. The house smelled of old age, a musty smell that was so strong it left a taste in your mouth, old food and unflushed toilets. The curtains were never opened. Granny Ball was totally blind. I don’t know how she became blind or how long she’d been blind but blind she was. She wore long black dresses and shawls. Her face was covered in a network of fine lines. She rarely spoke, not to me anyway, but one of my regular duties when I was a little boy was to go to her house at a certain time every day and lead her by the arm up to the Red Cow, the pub at the end of the street. It would take a quarter of an hour or so because she didn’t walk too well either. She’d dig her fingernails into my arm until it bled. I’d leave her there where she’d have five or six bottles of stout every evening and then someone else, one of her sons usually, would lead her home. Her small group of fellow drinkers was an interesting bunch. The woman who ran the pub was named Effie, I can’t remember what she looked like, and among the others there were two men who lived together in an old abandoned hut at the entrance to a long-abandoned mine shaft in a copse of trees on the hillside nearby. One had one leg and was known as Ianto Clown, the other was Billy Oof, pronounced like the reaction to a punch in the stomach. I know nothing of their circumstances but I quite like the idea of them living together. Apparently in the winter when it got dark early Billy would lead Ianto down the hillside along the path to the Red Cow by the light of a storm lantern and the people in the bar would chart their progress through the window by the moving light. What a strange clientele they must’ve been. I wonder what they talked about.

There was a man who lived in the billiard hall in Mill Street who was known to give local children, young boys, packets of crisps and bars of chocolate in exchange for looking at their penises. It was a well-known thing and parents would often warn their children not to partake of this arrangement. He was known to all as Dai the Bummer. There was a young woman named Dolly who lived with her mother opposite the Cow. Dolly was no looker and a little bit twp, as were all the family. Anyway, it came about somehow that she and Dai the Bummer met and struck up a relationship. Marriage ensued and Dolly went back to the billiard hall with Dai after the ceremony to live as man and wife. She turned up back home the following morning however, with her suitcase still packed, sobbing that Dai had forced her to indulge in ‘unnatural practices’ and that she would never go back to him. What amuses me about this story is that a woman, any woman, no matter how thick or unsophisticated, could marry a man universally known as Dai the Bummer and then react with total surprise and disbelief when he lives up to his epithet. What did she expect – Ronald Colman? It is of course also very interesting in retrospect that Dai the Bummer could have remained at large to carry out his paedophile activities unhampered as he did. In those days it was regarded by many as just another crime. People would talk about someone who’d been put away for ‘interfering with children’, as they called it then, with no more condemnation in their voice than if he’d been caught stealing lead off roofs. It was a different world then, in some ways better but in many ways much, much worse.

Granny Ball died when I was about eight. I remember Naine standing at the front gate waiting for Ool to come home from work so she could tell him the news. He was about fifty yards away waving to me when Naine shouted out ‘Your mother’s dead!’ I could see his face collapse in horror clearly even at that distance. Naine was not one to stand on ceremony.

After they were married Ool and Naine went to live in London. It was the 1930s and times were hard. They needed to work and some of Naine’s brothers were already there, working on building sites in the East End. Ool got a job with them and Naine went into domestic service, as many young Welsh girls did at that time. Her employer was a wealthy doctor. I don’t know much about it but Naine said that the work was backbreaking. They returned to Wales sometime before the outbreak of war in 1939. Ool told me that he was picking blackberries on Capel Hill with one of his brothers when someone brought him the telegram telling him he’d been called up. He and Naine must’ve been back in Pretoria Road, my mother living with them. There used to be a photograph of her in her WRAF uniform. She and a few others girls in uniform were horsing around in the country somewhere, my mother was straddling a kissing gate. She was a large, ungainly woman even then and though people say she was a looker I’m damned if I can see it.

Ool was sent to Africa. He spent the last three years of the war in Kenya and Madagascar teaching black soldiers to crew anti-aircraft guns. He’d been a gunner himself on the south coast in the earlier years of the war when invasion was threatened. He told me that they’d just bang shot after shot away in the general direction of the sky. In the entire war his crew only ever had one suspected hit. He found it difficult in the army at first. In training it became apparent that the Welsh weren’t particularly popular and Ool had to use his fists on more than one occasion to illustrate particular points. He was a tough bloke. He’d been brought up hard. After he’d settled in he found army life a dawdle. A lot of men, particularly those from more refined backgrounds, found the practical conditions intolerable but to Ool it was The Ritz. The food was regular and, by Ool’s standards, good. He had a comfortable bed and he didn’t have to spend ten hours a day carrying bricks up and down ladders. He was fine. He told me that at breakfast in the army the cook would just slam all the food onto one tin plate, porridge with milk and sugar with two sausages sticking out of it and a fried egg on top. Some men found this revolting and couldn’t eat it so Ool used to go around their discarded plates getting seconds. He was put on a charge for dragging some joker over the table in the NAAFI and blacking his eye after he’d made an ill-judged comment about Ool’s race and eating habits.

Ool always said that the years he spent in Africa were the best in his life. Being white immediately gave him status. Kenya was a colony at the time, of course, ruled by a wealthy white elite, and British soldiers were made very welcome. Imagine it, a rough, uneducated man like Ool, who had never known any luxury in his life, being invited to tea by delicate, well-spoken ladies on the verandas of their colonial farmhouses, served by black servants. No wonder Ool loved it. There was one family called the Roberts whom Ool had very fond memories of. He had a photograph of Mrs Roberts sitting on her lawn with two beautiful tame cheetahs. The Roberts’ farm was just outside Nairobi and Ool often had a tear in his eye recalling it. He actually lived among the Kikuyu, one of the two dominant tribes of Kenya at the time, the other being the Masai. He’d lay awake in his tent at night listening to the shuffling dancing and the singing, seeing the flickering of the fire through the open flap. Ool used to call his group of trainees his ‘Boys’. One was called Nicodema; I forget the others’ names. Nicodema would approach Ool’s tent in the early hours and hail him softly from the darkness: ‘Gunner Ball. Gunner Ball. Tombacco Gunner Ball!’ Ool would give him cigarettes and he’d disappear back off into the night. Ool told me that most of the white soldiers treated the blacks like dirt, punching them, beating the hell out of them for no reason. Ool was no bully and in fact felt a lot more kinship with the blacks than with most of his fellow whites. He liked and respected them and they reciprocated. He shared their food and drink. His affection for the black Kenyans stayed with him all his life and I am grateful for it. It meant that the insidious racism that I was brought up with, ubiquitous in the Valleys, didn’t work on me. Well, it didn’t engulf me anyway.

Ool found a lifelong friend in Africa too. It was one of those army friendships, a deep trust built up through the experience of common adversity. Ool’s mate was an Englishman named Bill Moody or just ‘Moody’ as Ool always referred to him. Moody was a great bloke according to Ool, and they kept in touch for the rest of their lives, if only by a Christmas card each year. We went to visit him once when I was a little boy. He lived in West Drayton outside Reading. I don’t remember him but I do remember that he took me for a ride in the sidecar of his motorbike. He and Ool met in training in England and spent all of the Africa years together. They got into many a scrape. The soldiers drank in a gin house called The Dew Drop Inn, which was well off the beaten track on the edge of a jungle. Ool told me that there was an ongoing feud between the British Tommies and their Canadian counterparts. It was quite a violent situation and a few serious beatings had taken place. One night while walking back from The Dew Drop in their cups, he and Moody came across half-a-dozen Canadians in a similar condition at the far end of a clearing. They’d already spotted Ool and Moody, so legging it was not an option. Ool took off his belt and wrapped it around his fist ‘buckle facing out’, expecting the worst, but as they approached each other Ool had a brainwave. He walked up to them sharply and said ‘What the hell are you doing here? We’re on night exercises. There’s live ammo being used. You’d better bugger off!’ It worked!