Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jonathan Ball

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

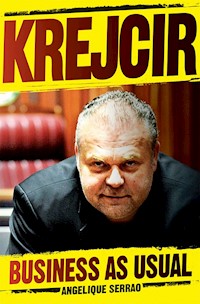

A powerful Czech multimillionaire, Radovan Krejcir fled his home country shortly after his arrest in 2005 on charges of fraud. He arrived on South Africa's shores in 2007, travelling under a fake name with a false passport, and avoiding extradition through pay offs. Krejcir fast began to make a name for himself within South Africa's underworld, but it was the murder of Teazer's boss Lolly Jackson in 2010 that brought his name to public attention. After three years and ten more deaths, Krejcir was finally arrested on charges of kidnapping and attempted murder. Yet it seems that even a jail cell is not enough to subdue the criminal kingpin: it is just business as usual. In KREJCIR, Angelique Serrao reveals why we have not yet heard the last of the worst crime boss South Africa has ever seen.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 479

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

KREJCIR

KREJCIR

Business as Usual

Angelique Serrao

Jonathan Ball Publishers

Johannesburg & Cape Town

Contents

Radovan Krejcir: Timeline of key events

‘With the right connections, money can buy you anything’Billionaire on the runFugitive at the doorAssassinations planned, assassinations thwartedThe death of Lolly JacksonGerman car specialist Uwe Gemballa lured to his deathBecoming a crime boss: Cyril Beeka gunned downThe chameleon witness: Marian TupyThe gruesome death of an innocent manGeorge Louca: Deathbed confessionKrejcir the target: An automatic weapon takes aimA close associate spills the beansThe cripple, the loose-mouthed Serb and the drug deal gone wrongThe bombThe arrestKrejcir is Al Caponed: When all else fails, call the taxmanKidnapping and torture of Bheki Lukhele: Krejcir’s Achilles heelConspiracy to murderA witness dropped from state protectionThe final takedown: Krejcir charged with Sam Issa’s murderKrejcir tries to escapeKrejcir’s luck runs outAnnexure - George Louca’s affidavit

Notes

Further References

Acknowledgements

Photo section

For my sunshine boys –

Even on days when the darkness in the world intrudes,you show me that there is light.

Angelique Serrao

Radovan Krejcir: Timeline of key events

June 2005: Krejcir escapes from the Czech police and flees the country.

July–September 2005: Krejcir makes allegations against the Czech Government from his hideout in the Seychelles.

21 April 2007: Krejcir arrives in South Africa and is arrested.

4 June 2007: Krejcir is released on bail from the Kempton Park Magistrate’s Court.

13 June 2007: Krejcir hands himself back to the police after his arrest warrant is reissued.

6 July 2007: Krejcir is released on bail after his second arrest one month earlier.

October 2008: Krejcir’s application for asylum in South Africa is refused; he appeals to the Refugee Appeal Board.

1 December 2009: Banker Alekos Panayi makes a statement implicating Krejcir in a money-laundering scheme.

5 December 2009: Private investigator Kevin Trytsman is shot at his lawyer’s offices.

8 February 2010: German national Uwe Gemballa arrives in South Africa and is reported as missing the next day.

3 May 2010: Strip-club owner Lolly Jackson is murdered.

September 2010: Krejcir’s extradition case is reopened after a ruling that the magistrate in the previous proceedings was not impartial.

27 September 2010: Uwe Gemballa’s body is found.

29 October 2010: First arrest takes place in Gemballa’s murder.

21 March 2011: Gangland boss Cyril Beeka is murdered in Cape Town.

22 March 2011: The Hawks raid Krejcir’s house.

25 March 2011: Krejcir hands himself over to the police.

28 March 2011: Krejcir appears in court over a case involving medical fraud.

17 April 2011: Lolly Jackson murder accused, George Louca, tells the media he did not kill Jackson.

20 September 2011: Ian Jordaan, Jackson’s former lawyer, is murdered.

28 September 2011: Jackson’s former business partner Mark Andrews is murdered.

10 October 2011: Drug dealer Chris Couremetis is gunned down by hit men.

12 February 2012: Krejcir is arrested for robbery.

26 March 2012: Louca is arrested in Cyprus.

16 April 2012: Fraud charges are dropped against Krejcir.

October 2012: Robbery charges against Krejcir are withdrawn.

24 July 2013: Automatic weapon attached to a car shoots at Krejcir; he escapes uninjured.

12 October 2013: Drug dealer Sam Issa is gunned down.

2 November 2013: Krejcir’s accomplice Veselin Laganin is shot dead.

12 November 2013: A bomb explodes inside Moneypoint, Krejcir’s front business.

22 November 2013: Krejcir is arrested for kidnapping, drug dealing and attempted murder.

25 November 2013: Krejcir appears in court.

February 2014: George Louca is extradited to South Africa from Cyprus.

May 2014: SARS seizes all of Krejcir’s assets with a preservation order.

5 November 2014: George Louca signs five key affidavits.

6 February 2015: Krejcir is charged with Issa’s murder.

21 April 2015: Louca reveals in court that Krejcir allegedly killed Jackson.

11 May 2015: Louca dies in prison.

26 September 2015: Krejcir tries to escape from jail.

12 November 2015: Three men found guilty of Uwe Gemballa’s murder.

27 November 2015: Krejcir’s Bedfordview and Bloemfontein houses are auctioned off by SARS.

December 2015: Krejcir is transferred to C-Max Prison, Kokstad.

23 February 2016: Krejcir is sentenced to 35 years in prison.

8 March 2016: Gemballa’s convicted murderer, Kagiso Ledwaba, escapes from Palm Ridge Magistrate’s Court.

20 April 2016: Krejcir loses appeal against his conviction and sentence.

chapter 1

‘WITH THE RIGHT CONNECTIONS, MONEY CAN BUY YOU ANYTHING’

These are the words of a dead man.

He was a petty criminal. A thug. A hit man. Someone you shouldn’t trust. Even his identity wasn’t something you could be sure of. He had multiple names: George Smith, George Louca, George Louka.

Take your pick. They are all right, and all wrong, depending on whom you speak to.

His words can never be proven – he is dead, after all, and he was not someone to trust. But, there his words are, in black and white, signed and stamped by a commissioner of oaths.

They were uttered in his dying days, in a jail cell, witnessed by his lawyer, who swore the man had transformed. Because Louca had nothing left to lose – the cancer that had started in his lungs had spread. It was now in his throat and he could barely talk. He was a shadow of the big brute of a man who had been terrorising Bedfordview before he fled the country in 2010. There was no hope for him. He would die, alone, in a jail cell, far from his family in Cyprus.

And, with death so close, he was no longer scared. He would write down a little of what he knew about the man whose very name instilled fear in those who heard it: Radovan Krejcir.

If you believed Louca, Krejcir was the man who had led him to this point of no return. Krejcir was a man so dangerous, it was only Louca’s inevitable death that would make him spill the beans.

Most of Louca’s words would never be heard in court, though. There would be no prosecutions. No one would pay for what had happened, for the blood that had been spilt. But Louca’s words were there, written down, so that, one day, everyone would hear what he had said in his dying days.

That day has come …

George Louca met Krejcir in April 2007. They shared a cell at the Kempton Park Magistrate’s Court. Louca had been arrested on charges of theft. Krejcir was a fugitive from the Czech Republic. He was red-flagged and arrested as soon as he set foot in South Africa.

According to Louca,1 ‘Krejcir introduced himself as a businessman of considerable wealth and influence in Europe who had extensive international business experience. He advised that upon his release from custody he intended to establish businesses in South Africa.

‘Over a period of several days Krejcir and I engaged in discussion. It became apparent that Krejcir was concerned by the fact that he knew almost no-one in this country; that his command of the English language was limited; that he had no prior experience of the South African business environment and there were issues around his immigration status. For these reasons he expressed interest in the possibility of using my services. I offered to assist him in exchange for the promise of financial reward.

‘Krejcir and I were locked up in our cell at night but for most of the day we were free to walk about as we pleased. We had access to the fenced yard at the Kempton Park Magistrate’s Court.

‘One day a young girl, approximately 15 or 16 years of age, appeared at the gate of the yard and signalled for my attention.

‘When I approached her she addressed me in English, asking whether I knew “Mr Radovan”. Once it was confirmed that I knew Krejcir, the girl passed me a letter through the gate and instructed me to deliver it to Krejcir.

‘Upon receipt of the letter, Krejcir commented that it was written in Czech but appeared, in his opinion, to have been written by someone using one of the free language translation software applications available on the internet.

‘Krejcir said that he had been offered an opportunity to guarantee his release on bail in consideration for payment of a bribe.

‘He was interested in exploring this opportunity and if possible to come to an arrangement which would ensure his release, but at the same time he was cautious and concerned as to whether the person (or people) making the approach could be trusted.

‘As he explained it, Krejcir was expected to make telephone contact with a person whose number was supplied in the letter.

‘For this reason, Krejcir asked me whether I could source a mobile phone which could be used for this purpose. I obtained a cell phone.

‘He asked me to make the telephone call, on his behalf, to the person whose number appeared in the letter. He seemed concerned that with his limited English he might be at a disadvantage in communicating clearly and also be unable to assess whether the person or people he was dealing with could be trusted.

‘I called the number provided in the letter and spoke to a woman.’

They came up with an arrangement that an upfront payment of R1 million would be made by Krejcir and, following his release, a further R3 million, which Krejcir allegedly later renegotiated to R500 000.

Louca was in charge of handing over the bag with the money.It was about 10 pm and dark outside. He was travelling with a woman called Ronell, who had helped source the cash through a loan.

They were in her Mercedes, just as they had planned, awaiting further instructions. The bag of money was in the car. Louca had opened it briefly and noted that it contained a substantial amount of cash.

The phone rang. It was the woman. She told them to drive onto the R21 highway towards Pretoria and stop at an Engen petrol station on the way. They stopped at the garage and waited. Another call came. They were told to get back onto the R21. They drove for a bit and were then instructed to pull over by the side of the road.

Louca was told to get out with the bag and walk a short distance away from the car. ‘I did as I was instructed and though it was quite dark … I could see the lights of a vehicle which had stopped at a distance behind the Mercedes.

‘I walked about 10 or 12 metres from the rear of the Mercedes carrying the bag, before placing it on the side of the road. Then I returned to the Mercedes.

‘Ronell and I waited briefly in order to ensure that the bag was collected. Looking behind us … I could see someone picking up the bag.

‘… We drove off.’

Radovan Krejcir had just secured his freedom. South Africa, it seemed, was a country that spoke to his values, where he could, and would, do anything. This was the place for him – a place he could call home.

chapter 2

BILLIONAIRE ON THE RUN

Radovan Krejcir was young, and he was rich – a Czech billionaire still in his thirties. The world was at his feet and he knew how to live large. He had a gorgeous bombshell of a wife, drove around in red Ferraris and could be spotted in the most fashionable districts of Prague. Over six feet tall and with a witty sense of humour, he was the kind of man who turned heads.

Back in the 1990s Krejcir wasn’t yet known as an underworld kingpin. In the Eastern Bloc country, a part of the world that has gained a reputation for creating sinister mafia Dons, he was small fry, an unknown.

But that would change – and embarrassingly so for the police – in the European summer of 2005, when, overnight he became a household name.

Radovan Krejcir was born in DolníŽukov, a village in the Czech Republic, on 4 November 1968. His mother, Nadezda Krejcirova, was a successful businesswoman and one of the wealthiest women in the country. His father, Lambert, was a member of the Communist Party during the socialist era.

Krejcir graduated from the University of Ostrava as an engineer. He married Katerina Krejcirova, a beauty with black hair and green eyes, who was eight years his junior. They had two children, Denis, who was born in 1992, and Damian, born in 2009.

By the time he was 21, Krejcir had a business selling food, drinks and cigarettes, and, allegedly, Smarties. Like his mother, he had entrepreneurial flair and his business flourished, developing into a network of companies trading in all sorts of goods, particularly fuel.

Krejcir had amassed a fortune by the time he was 30, most of it made during the wave of state-industry privatisation that followed the 1989 Velvet Revolution, which saw the overthrow of the communist government in the former Czechoslovakia.

He flashed his wealth around, acquiring numerous properties and luxury cars. His home was a villa near Prague, a luxury 2 000-square-metre estate partially carved into a hillside, estimated to have cost $15 million. There were squash and basketball courts, indoor and outdoor swimming pools, and an enclosure for a pet tiger. A giant aquarium sported reef sharks and a large moray eel.

It didn’t take long before Krejcir was in trouble with the law. Slowly, the image of a successful young businessman became tarnished as it emerged that he had been infiltrating the Czech criminal underworld. Police investigations were opened against him for fraud, tax evasion and counterfeiting.

His company, which imported oil, mainly from Germany and Russia, was accused of not paying taxes and owed the state millions of Czech crowns. Krejcir was also accused of various financial crimes, such as transferring huge sums of money to the Virgin Islands to avoid paying tax.

He was first arrested in 2002 and spent seven months in jail before being released on a technicality. He was arrested again in September 2003 and spent a year in custody for loan fraud. He and his accomplices were suspected of stripping a company known as Technology Leasing of its assets.

In January 2011 the Municipal Court in Prague convicted Krejcir of breach of trust and sentenced him to eight years in jail. This was one of many crimes of which he was found guilty in his home country. He never served the sentences.

In 1996 Krejcir acquired possession and control of shares that he was contractually obliged to return to a company called Frymis. He failed to return the shares, causing damage of approximately 75 million Czech crowns (approximately R30 million). Much later he was eventually convicted on a charge of fraud relating to these shares, and sentenced to six and a half years in prison, which was later reduced on appeal to six years.

He was also alleged to have been one of the organisers of customs-duty evasion by a fuel importer registered in the Czech Republic. According to SARS investigators, on 3 December 2012 he was convicted for his involvement, in absentia, and sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment and a fine of 3 million Czech crowns.

Krejcir was also charged with having ordered and organised the abduction of a businessman, Jakub Konecny, who was allegedly forced to sign blank promissory notes, and other documents in Krejcir’s presence. He was convicted and sentenced to six and a half years’ imprisonment for blackmail.

The fraudulent activities were one thing, but the pile of dead bodies that started to accumulate around him was more concerning. A key witness in a tax-evasion case against Krejcir, Petr Sebesta, was found murdered with a cartridge in his hand, a typical warning from the Czech mafia.

Krecjir was arrested in 2002, when he spent a few months in jail before being released. He was found guilty of crimes in his home country years later, after he had fled the Czech Republic. During his first stint behind bars in 2002, his father, who owned a printing business, mysteriously disappeared. A well-known and influential football-club owner, Jaroslav Starka, was arrested in 2006 for the murder. Police believed Lambert had been kidnapped to force his son to pay up his business debts. Some believe Lambert had a heart attack when he was bundled into the trunk of the kidnapper’s vehicle. His body was never found and Krejcir said he believed Czech state agents dissolved him in a vat of acid.

The football-club owner denied any involvement in the abduction, saying he and Krejcir were on good terms.

The so-called godfather of organised crime in the country, Frantisek Mrazek, was murdered in a professional hit in January 2006 when a sniper shot him outside his office building. Czech media pointed fingers at Krejcir, saying he blamed Mrazek for his father’s death. South African writer and researcher Julian Rademeyer in 2010 said Krejcir laughed when asked if he had anything to do with the killing.1 Krejcir pointed out he had been in the Seychelles at the time of the murder: ‘Yes, I shot one bullet from the Seychelles and the bullet travelled all the way direct to his heart. I’m very good … I saw this guy twice in my life. We never had a fight. It is the same situation as my father. They killed him and afterwards said it was my criminals. All the time it was the top government and secret service guys.’

Krejcir claimed that he was the victim of a political vendetta, spurred on by a prime minister whose ascent to power he had, ironically, helped fund. He admitted having funded the election campaign of the Czech Social Democratic Party candidate, Stanislav Gross, in a deal whereby Gross would hand Krejcir control of the state petroleum company, CEPRO, in the event that he was elected prime minister.

Krejcir claimed Gross had refused to honour the agreement and asked Krejcir to hand over the promissory note. Incensed, Krejcir refused and threatened to go to the media.

‘During July 2002, I was arrested on trumped-up charges of fraud and detained for a period of seven months during which I was physically and psychologically tortured so as to reveal the whereabouts of the promissory note,’ Krejcir is quoted as saying in Lolly Jackson: When Fantasy Becomes Reality.2 ‘During the period of my incarceration, my father was questioned as to the whereabouts of the promissory note. He was unable to supply any information … and was abducted and eliminated as a result.’

Some years later, just before midnight on 18 June 2005, 20 balaclava-clad security police and state prosecutors entered Krejcir’s villa. They were investigating a tip-off that there were plans to kill a customs official who was a witness in one of the fraud cases they were investigating against Krejcir.

The media reported that Krejcir watched them as they conducted the search operation, following the police as they searched his mansion. A few hours later, the police realised he was gone. It was widely reported that he had asked to go to the bathroom and escaped through a window. However, Krejcir later said that corrupt police officers had allowed him to leave. He told Rademeyer that there was no window in his bathroom.

‘I don’t know how you could escape from 20 guys with machine guns and masks on their faces.’ He told Czech journalist Jiri Hynek3 that the reason the police wanted to arrest him was that the Social Democrats did not want to repay him the money he had lent them.

He said the police asked him for money, telling him they would let him go. He then pretended to look for the cash, walked out the back door and didn’t return.

According to Czech press reports, the morning of his escape he ate breakfast at a friend’s house nearby and was spotted filling up a Lamborghini at a petrol station in Slovakia three days later.

A few weeks later, Krejcir emerged in Istanbul. He said later that he had stayed in the Czech Republic for a week. From Prague he went to South Bohemia and Moravia. From a mountainside cottage in Beskydy friends helped him flee the country by falsifying a passport, under the name of Tomiga. He entered Poland by bicycle, took a train to the Ukraine then flew to Istanbul.

By then, everyone in the Czech Republic knew who he was. His escape was a national embarrassment, and it cost police chief Jiri Kolar his job.

Searching his villa, the police had got a picture of everything Krejcir had allegedly been up to. The house contained a secret strongroom packed with weapons, jewellery, share certificates and classified police documents. A police officer later testified in court that they had also found a parliamentary ID card and DNA was found on skiing goggles that matched that of the entrepreneur who had vanished, Konecny. According to TV Nova,4 Konecny had disappeared in March 2005.

The policeman also said they found a briefcase containing notes, diagrams and plans of criminal activities, and forged passports.

In a factory Krejcir owned they found billions of crowns in counterfeit currency. Mixed into the boxes of cash was 8 million crowns (about R3 million) in genuine currency. Krejcir told Rademeyer the boxes of cash were an elaborate birthday gift for a close friend.

From Istanbul, Krejcir flew to Dubai where he met up with his wife, who was facing complicity charges, and son. They flew to the Seychelles.

Ensconced in a five-star hotel overlooking the turquoise seas of the archipelago, Krejcir had escaped the clutches of the law. He was secure in the knowledge he could not be touched because the Czech Republic had no extradition agreement with the small island state, whose citizenship he purchased in 2006. He even felt bold enough to thumb his nose at the Czech authorities by giving regular interviews in the Czech media from his island retreat.

He was set to live out his days in tropical luxury. But, for the man who had become so used to wheeling and dealing, the slow pace of island life was not quite the paradise he had thought it would be.

Hynek, the Czech journalist, visited him and remarked that he did not think that Krejcir was satisfied in the Seychelles: ‘It’s a type of prison for him because he can’t go anywhere.’

‘It was so boring there, like being a prisoner in paradise,’ Krejcir later told Rademeyer.5

Perhaps it was out of boredom, or an act of revenge after Czech police arrested five people believed to be his closest accomplices and declared that he was the ringleader of a dangerous gang, but, either way, Krejcir wrote a book, Radovan Krejcir – Revealed, in which he describes the Social Democrats’ actions6 as the country’s equivalent of the Watergate scandal. Czech Finance Minister Bohuslav Sobotka said Krejcir had lied to get back at the party for breaking up his crime ring.

In the book he disclosed that he had lent money to the Social Democrats in return for special favours. ‘I am certain that the present political leadership and the police knew I was beyond their reach the minute they heard I was in the Seychelles. All their media statements about trying to get me extradited were just a smoke screen for the public. I consider myself innocent.’7

People in the Seychelles didn’t know who he was, until the Czech journalists started arriving. He wrote in his book how, after the journalists came, he would go to the pub and people were silent and looked at him with fear in their eyes.

Soon there was trouble in paradise. In February 2007, Czech authorities signed an extradition treaty with the Seychelles, which would come into effect six months later. It was time for Krejcir to move.

He applied for passports under the name Egbert Jules Savy for himself, Sandra Savy for his wife and Greg Savy for his son, which he received without difficulty.

Just as his departure from the Czech Republic had caused enormous embarrassment for the state, it was the same story when he left the Seychelles. Le Nouveau Seychelles Weekly8 emanded that President James Michel explain how it was possible that Krejcir had been issued legitimate passports under a false name: ‘The public is clamouring for an explanation as to how a legal passport could contain a false name.’9

A senior official from the Department of Immigration was allegedly behind the issuing of the passport. Krejcir regularly frequented the private offices of the civil servant at Independence House, the government offices, and he was a guest at the man’s home. The passports were issued when a certain Michel Elizabeth, described in the local press as a ‘diligent incorruptible civil servant’ was on holiday. He was apparently asked to take annual leave during that time.

Passports in hand, Krejcir left the island of Mahé aboard his yacht, officially heading for the Amirante archipelago, where he boarded another vessel bound for Madagascar.

Seychelles media learnt that as soon as Krejcir had left Mahé, a letter was sent to the non-existent Egbert Jules Savy demanding that the passport be returned to the immigration authorities for cancellation.

Police in the Seychelles were informed and they issued a red alert to Interpol identifying Krejcir as the holder of an illegally obtained passport.

‘Krejcir, it seems, had not endeared himself well with some senior members of the local police, even though Krejcir had provided foreign currencies to import new police vehicles,’ wrote Le Nouveau SeychellesWeekly.10

There was speculation that the Seychelles authorities had allowed him to leave the country, and then alerted Interpol to get rid of him and make him someone else’s problem.

In Madagascar Krejcir boarded a flight and on 27 April 2007 at 5.15 pm, he arrived in South Africa.

chapter 3

FUGITIVE AT THE DOOR

The police were waiting. They knew who he was. His passport with a fake name, his beard and his glasses fooled no one. The Czech Republic’s most wanted fugitive was at our door. He was arrested as soon as he set foot in Johannesburg.

The Czech authorities were ecstatic. Czech intelligence officers said they had been monitoring him for a long time and had been waiting to pounce. They said police from five countries cooperated on the case. Interior Minister Ivan Langer called a press conference and handed out photos of a detained Radovan Krejcir.

‘He did not put up any resistance and was very surprised,’ Langer said.1

The Czech Republic now had 40 days to lodge an extradition request with South Africa to bring Krejcir home.

‘I anticipate that an extradition request will be processed in the coming days. We are waiting for word from our colleagues in South Africa as to whether they want any additional information. If they don’t need any further data, then we will file our request and issue an arrest warrant,’ said Justice Minister Jiri Pospisil.2

It looked like Krejcir’s time on the run was up.

He appeared in the Kempton Park Magistrate’s Court two days later and his case was immediately postponed. A special delegation from the Czech Republic arrived in South Africa in a bid to stop Krejcir from being released on bail. Johannesburg High Court Senior State Advocate Beverley Edwards was tasked with handling the case against the fugitive in the lower court.3

Krejcir’s legal team, headed by Advocate Mannie Witz, argued that he was no longer a citizen of the Czech Republic, as he had given up his nationality when he became a citizen of the Seychelles. Witz argued that Krejcir was now protected by South Africa’s Constitution.

Krejcir sat in the dock and smiled at foreign reporters who had travelled to South Africa to witness the case. He was 38 years old; he looked young and was smartly dressed despite having spent a month in jail awaiting trial.

The Czech Government told the court that Krejcir allegedly defrauded the country of about 9.5 billion crowns. The Czech authorities had four warrants of arrest for him.

Krejcir’s lawyers claimed, however, that he was trying to enter South Africa to receive medical attention. He needed an MRI brain scan. One of his attorneys, Hugo van der Westhuizen, said Krejcir was experiencing stroke-like symptoms that involved intense headaches and memory loss. The symptoms were at their worst when he was under extreme stress, the attorney said.

At one of his court appearances, a special delegation of state and defence witnesses from the Czech Republic were ready to testify. Government ministers, diplomats, senior police officers, and Krejcir’s mother and his son Denis, were in court to hear his fate. Then, in what was described as a shock twist, South Africa’s most wanted international fugitive was released on a legal technicality. It was June 2007 – his lawyers argued that the 40 days the state had had to receive extradition papers from the Czech Republic had elapsed. The magistrate ordered Krejcir to be released from prison.

A shocked South African Police Service (SAPS) spokesperson for Interpol, Senior Superintendent Tummi Golding, said they planned to rearrest him. For days, the state had no idea where he was. All airports were alerted and the police began to search.

It turned out he was not plotting his escape, however. He was buying blankets to donate to old-age homes, and soccer balls for underprivileged children. His next charity crusade was to start soup kitchens. His lawyers made sure the media and courts knew every detail of his charity work during his stint of freedom. It had probably been a clever marketing ploy to show the authorities he cared about the country, and would be a citizen worth having on our shores. But, after eight days, he handed himself over to the police.

A Czech delegation comprising state attorneys Petra Pavlanova and Vladimir Tryzna, two Justice Ministry clerks and two policemen argued persuasively in the Kempton Park Magistrate’s Court that Krejcir was wanted in his home country for fraud, tax evasion, counterfeiting, kidnapping and conspiracy to murder – all to no avail. Magistrate Stephen Holzen granted him R1 million bail on 6 July on condition that he report to the Lyttelton Police Station twice a week.

Holzen believed Krejcir’s version of events and said it was clear he was running away from persecution rather than prosecution and he banned Interpol from arresting him. Considering it could take up to three years to finalise the extradition, it would not serve the interests of justice to keep Krejcir in detention, he said.

The state argued that Krejcir was a flight risk, that he had entered South Africa illegally, with a forged document under a false name, and that he had no emotional attachment or financial assets to keep him in South Africa.

Holzen said he found it strange that the charges against Krejcir were very old, some going back to 1994, while he was still living in the Czech Republic, and yet he had never been arrested there for the charges the Czech Government were now placing before his court. He said Krejcir had been legitimately issued a Seychellois passport, even if it were under a different name. Krejcir, he argued, had in the meantime bought properties and a business in South Africa. And he had told the court of his desire to bring his son and wife to the country permanently.

When he heard he was allowed to go free, Krejcir was all smiles. He told journalists he was impressed with the South African justice system: ‘This is a country under constitutional law … and I am convinced that I have done the right thing. It’s nice, very nice. Next step? Now I will pay bail and I have to take some rest,’ Krejcir said.4

He said he was convinced more than ever that he would never go to a Czech prison.

As soon as he was out of custody, Krejcir applied for asylum in South Africa, claiming he would be persecuted in his homeland and that the former government had ordered his father’s murder.

The following year, Holzen would pass a judgment refusing to extradite Krejcir.

For two years, Krejcir appeared to lie low. There was not a peep from him in the press. He bought a magnificent home in Kloof Road, Bedfordview, commanding 180-degree views of Johannesburg. He bought up businesses, one being Moneypoint, a gold and jewellery exchange opposite the busy Eastgate Shopping Centre. Katerina joined him from the Seychelles and soon they would have their second son, Damian.

However, according to the testimony of many who became involved with him around this time, Krejcir was busy setting himself up in the South African underworld. He made friends with characters who knew how to make fast money, by every means possible, and he got cosy with members of the Crime Intelligence Division of the SAPS.

He befriended spies and, in doing so, infiltrated the hidden depths of South Africa’s criminal world. His charming personality, wit and the lure of millions in his pocket drew people whom he needed to him. Krejcir never had a problem making new friends.

But the friend who was the key to opening all the doors for him was the man he met in the jail cells at the Kempton Park Magistrate’s Court: George Louca (or Louka or Smith, depending on which ID book he decided to use at any given time).

Louca was a well-connected low-life who wheeled and dealed his way through the Bedfordview mafia. Louca’s ID, under the surname Smith, was issued in January 2006 and it gave his place of birth as South Africa. But those who knew him said there was no doubt he was an immigrant from Cyprus. It emerged he had been a special-forces operative in the Cypriot military and had been identified as a professional hit man in the Gauteng underworld. Louca had also allegedly served seven years in a Swiss prison for drug trafficking. Staff at a Bedfordview cafe told The Star5 that Louca was aggressive, but they put up with him because he was strip-club king Lolly Jackson’s friend. ‘He was like an animal. He was a drug addict,’ said the manager.

Their meeting in jail was one of the most fortuitous encounters of Krejcir’s life and they developed a strong bond.

According to statements Louca later made to his attorney, Krejcir had just been arrested and brought to the cells of the Kempton Park Police Station (which shares the building with the magistrate’s court) when they met. Louca had meanwhile been arrested on charges of theft. The two were both foreign born and this drew them to each other, along with the fact that Krejcir boasted about how rich he was. Louca had experience helping well-pocketed men – for a fee.6

It was Louca who introduced Krejcir to Bedfordview. He found him the R13 million mansion that Krejcir would call home for the next six years and he introduced him to the key players in Johannesburg’s then fragmented underworld.

Krejcir soon identified a restaurant in Bedford Centre, the area’s most upmarket shopping mall, where he could spend his days eating good Mediterranean food and meeting the suburb’s cosmopolitan residents. It was the kind of place where wealthy immigrants from all over the world gathered and talked business. The Harbour restaurant was perfect. Situated five minutes from his newly acquired mansion, it had the type of food he enjoyed and a clientele that fitted in with his plans for expansion.

According to his own statements, it was also Louca who helped ensure that Krejcir would not be deported to the Czech Republic.

Louca saw a man he could make money from, and Krejcir saw someone who could help set him up in this strange new country he was determined to make his home. And, within a month of landing in South Africa, Krejcir’s tentacles, with the help of Louca, had already infiltrated the criminal-justice system.7

The alleged bribery to secure bail sealed the deal. Louca carried out the payment and proved he could be trusted by Krejcir.

Louca said in his statement that in August 2007 he was waiting outside the courtroom for his case to be called when he was approached by a person involved in the bribery. Louca was told: ‘Your friend has let me down; he hasn’t made the other payment.’

A few days later, Krejcir asked Louca to go with him to meet the person in Pretoria to ‘sort out the problem’. In his affidavit, Louca said:

I accompanied him to a restaurant. I do not recall the name of the restaurant … Krejcir asked me to remain at the front section of the restaurant and to keep an eye on him while he approached and spoke with the person, who I noted, was already present and seated at a table. I could see both clearly. They spoke together for some time, after which Krejcir rose from the table and left the restaurant accompanied by me.8

Louca said that Krejcir had told him, while driving from the restaurant, that they had agreed on a reduced payment of R500 000 from the original R3 million he had asked for.

Confident that he was now in South Africa to stay, Krejcir began to climb the social ladder. His first move: to make friends with the powerful and eliminate any enemies from his past who still posed a threat to his new life.

chapter 4

ASSASSINATIONS PLANNED, ASSASSINATIONS THWARTED

They were heavies, two men who helped out in tense situations. And the foreign man in the company of George Louca looked like someone they could do work for, make some easy money from.

Louca explained to the two security guards that the man he was with, Radovan Krejcir, was a billionaire and that he was the ex-president of the Czech Republic.

This was great stuff, they thought, and they made sure they swopped telephone numbers before the evening was done.1

It was 4 November 2007 and it was Krejcir’s birthday, the first birthday he was spending in his newly adopted country, and he was celebrating at The Grand, an upmarket strip club in Sandton. The two men were security guards at the club and they knew Louca well. That night Louca was causing trouble as usual. He had got into a fight with Mike Arsiotis, an employee of Krejcir, and they had to kick him out of the club. Later Louca apologised and the bouncers let him back in.

The next day, Krejcir invited the security guards to his house. He was looking for men like them who could help him out in difficult situations.

And it soon turned out he would need them. A few months later, in March or April 2008, the two men got a call from Louca asking them to meet him at Bedford Centre. He explained that Krejcir was having some trouble with a Russian man, Lazarov, and needed backup. They met at the Harbour, where Krejcir was known to spend most of his days.

Krejcir informed the two men that Lazarov had told him that he had been sent to South Africa under instructions to kill him. But the Russian man didn’t want to kill Krejcir. Instead, he wanted his money. If Krejcir paid over hundreds of thousands of euros to him, then he wouldn’t carry out the hit, Lazarov had told him.

Lazarov had asked to meet him, but Krejcir was worried that the meeting was a set-up, that Lazarov might come with someone else and carry out the hit while Krejcir was off guard.

The security guards and Louca were sitting at a nearby table, ready, in case there was any trouble. Then Lazarov arrived, alone. He was a short man, in his 30s with fair hair. He sat down next to Krejcir and they spoke for half an hour. Lazarov then got up and left.

Krejcir told the men afterwards that the Russian had repeated to him how he had been sent by someone in the Czech Republic to kill him and that he wanted money from him.2 Krejcir asked them to follow Lazarov and find out where he was staying. The three men got into a white bakkie that was fitted with blue lights.

‘George also had a police card as well, so everyone would think we were cops,’ the guards later said in an affidavit.3

They drove to a hotel in Katherine Street in Sandton and spotted Lazarov outside.

‘George then stopped the bakkie and jumped out and grabbed this guy and before the guy could do anything, George brought him to the bakkie and opened the back door and I helped to pull him in,’ one of the guards said.4 They then drove, with the blue lights flashing, to a house in Boksburg. Krejcir arrived shortly afterwards.

There are different versions of what happened next. The guards and Louca gave different accounts years after the kidnapping had happened. They all wrote sworn statements, which were signed by a commissioner of oaths. One thing they did all agree on, though, was that Lazarov was tortured.

According to Louca, the man who carried out the torture was Krejcir; according to the two guards, it was Louca, while Krejcir sat and watched. According to the guards’ version of events, Louca started asking the Russian man questions. He was hit after each question.

‘The guy fainted and when he opened his eyes I took water and woke him up. He said he wanted vodka and George was laughing. George took a beer from the fridge and gave it to him,’ one guard said.5

Louca repeatedly asked Lazarov who had sent him. The guard held him down while George hit him.

‘I may also have hit him, but I don’t remember,’ the man said. ‘George wanted to stab Lazarov in the hand with a screwdriver and I stopped this from happening.’6

Krejcir also asked questions and every time the man answered, Krejcir accused him of lying, the men said.

‘I was making some hot water and sugar to drink and the kettle was boiling. George then took the kettle of boiling water and poured it on him [Lazarov] … He poured it into his ears first and when the guy started crying, he poured it into his mouth. Krejcir was watching all of this.’7

The guard said he grabbed the kettle away, scalding himself in the process.

‘George wanted to stab this guy with a screwdriver,’ he said, but the other guard screamed at him to stop, because George now wanted to stab him in the eyes.8

Lazarov eventually started to talk. ‘Lazarov told Krejcir that he had followed Krejcir to the Seychelles to kill him and that he brought a gun into the Seychelles hidden in a generator,’ the guard said.9 He said he had been paid about €500 000 by someone in the Czech Republic to kill Krejcir.

Louca said Lazarov had admitted to being a hit man and that they should ‘take him to the bush and kill him and make his body vanish’.10 But the two guards say they protested – they had been to his hotel and there were security cameras, so they would be the first suspects.

Instead they decided to take the Russian man to Bedfordview Police Station, where Krejcir would lay a complaint that he had come to try and kill him. Glad to be alive, Lazarov cooperated. He didn’t breathe a word of what had been done to him.

The guards were paid R20 000 each for the part they played in the kidnapping.

That is the guards’ account. Louca remembered things slightly differently, however. He said that, after the meeting at the Harbour, Krejcir had told him he did not feel safe with Lazarov, that he knew too much about his activities and he believed Lazarov posed a threat to his life.

He said that the Russian answered some of Krejcir’s questions when he had been kidnapped, but refused or could not answer others.

‘Krejcir began to torture him with a screwdriver which he pushed into Lazarov’s neck below his ear,’ Louca said.11 He said that it was Krejcir who beat Lazarov up and tortured him with boiling water:

He poured boiling water over Lazarov’s ear and the side of his face, all the time asking Lazarov to tell him who had sent him here to kill him. This went on for approximately an hour, during which he continued to torture him alternatively beating him and pouring boiling water on the side of his face until the man told Krejcir that he had been hired by Pivoda.

I should mention that Krejcir knew Pivoda. They had at one time been friends in the Czech Republic and shared a keen interest in riding and racing fast motorbikes, but had later fallen out with one another.

Krejcir told me that he believed that Pivoda had learned of a planned attempt on his life, in Prague, which had been arranged by Krejcir earlier in the year and that it was for this reason that Pivoda had, in turn, hired an assassin to kill Krejcir.

He said Krejcir gave orders to the security guards to kill Lazarov and throw his body into the Loskop Dam.

Louca claimed that it was he who had said that Lazarov should not be killed, as he had been abducted outside of a hotel where they may have been captured on security cameras kidnapping him.

They called the police and Lazarov was arrested. After a few months in jail he was deported to Russia when Krejcir withdrew the charges against him.

It was not the first time Louca had been called to help Krejcir out in sticky situations. Except, according to Louca, it was Krejcir ordering the hits.

Going by the sworn statement of a Bedfordview resident who let his flat to a man called Tony, who was born in the Czech Republic and an employee of Krejcir, Louca was believed to be Krejcir’s hit man. Krejcir was paying the rent for the flat that Tony lived in.

The owner of the property said that in 2009 he got a call from Tony asking to meet him at a restaurant called Medium Rare, in Van Buuren Road. Louca, who was someone he recognised from living in the area but did not know personally, was also there.12

‘I noticed that there was some sort of atmosphere between Tony and George, as if they were challenging the pecking order below Radovan Krejcir,’ the man said.13

In his sworn statement, the man said: ‘George Smith came right out and said, “Radovan wants to employ you to do a job for him. He wants to send you overseas to do a hit on a guy and wants to know how much of a fee you will charge for doing this.” I was completely taken aback by this, but did not want to immediately shut off the conversation, as I was curious as to what they were talking about.’

It was not made clear why Louca would approach this man to do a hit, and the landlord indicated in his statement that he, too, did not understand why he had been asked to do this. Louca’s strange behaviour was remarked upon by many who had dealings with him. Perhaps it was his alleged drug use that led to this odd behaviour, or perhaps the nature of the criminal world he was surrounded by meant that talking about murdering someone didn’t seem out of place to him.

Louca then told him they would send him to Germany to do a hit and a weapon would be provided there.

‘The way he said this, it was clear he was bragging about their abilities to set up hits and arrange weapons and so on. He said they had been doing this for a while.’14

Tony told him Louca was Krejcir’s hit man. But Louca claimed he was rather ‘an agent, a fall guy’ for Krejcir and he would arrange payment, trips, weapons and so forth.

The man said he later made it clear to Tony he would not help them and that he thought he was crazy getting mixed up with this kind of thing.

After he turned down the job, he said that Krejcir stopped paying the rent for his flat. The landlord said he decided to tell someone what had happened. He knew a man called Kevin Trytsman who he thought was an employee of the National Intelligence Agency, but who later turned out to be another employee of Krejcir. The landlord met with Trytsman and told him about the planned hit.

He said that because the rent wasn’t paid things became tense between him and Krejcir. He was owed R15 000 and argued with Krejcir about the money over the phone.

‘Krejcir said … something like, “Listen, everything will be taken care of, we will arrange the flights, the weapon will be handed to you and we will give you addresses, photographs, everything.”’15

The man said he was not in that line of business and that he just wanted his rent paid. They swore at each other.

He said he later got a call from a powerful man, a security expert with political connections, a man called Cyril Beeka. Beeka told him he would sort the situation out and the man’s rent money was paid into his account the next month.

Tony fell out with Krejcir too and left the country at some point.

Louca said that he visited the Czech Republic on two occasions for Krejcir.16 The first time was to resolve some concerns over payment for a garage owned by Krejcir and he stayed with Krejcir’s mother. That trip was uneventful, Louca said.

The second time, he flew to Prague with Tony. They were told they were going to make payments for Krejcir. They met up with a third man, called Tasso. Louca said that they arrived at a hotel and that night Krejcir called him and told him to go to their hired car in the hotel parking area and unlock the boot, then to leave the car for a while. He had to return later and remove a package, which he was told to give to Tasso.17

Louca did as he was told. He looked inside and said he found cash – €55 000 – and two pistols. He called Krejcir to ask about the weapons. Krejcir refused to tell him anything and told him to give the package to Tasso.

‘It was obvious that Krejcir had a different agenda from that which he had disclosed to me in South Africa, prior to our departure. It appeared to me that an assassination had been planned,’ Louca wrote.18

Tasso, he said, told him that he had orders from Krejcir to secure the services of an assassin who was to kill three men in the Czech Republic.

‘I told Tasso that I was not prepared to place my hands in anyone’s blood; nor would I take part in any plan to murder; and further that I did not care whether Krejcir became upset or ugly as a result of my refusal to cooperate.’19

He said he told Tasso there had been only €5 000 in the boot. The men packed up and left. When Louca arrived back in South Africa, he said he gave Krejcir the remaining €50 000 back.

The event was the start of a souring in their relationship, Louca said: ‘I complained that he had not been open with me and should not expect me to participate in or be involved with murder. My position on this matter resulted in a falling out with Krejcir. He was angry with me and frustrated by my conduct.’20

chapter 5

THE DEATH OF LOLLY JACKSON

Lolly Jackson, the ‘king of teaze’, looked down into his own grave.

He was in a tuxedo, a white rose in the lapel, and his head, cast downward, was set at the perfect angle to allow him a long look into the six-foot chasm that held his mahogany casket.

It was just a black-and-white portrait, The Don, as his family called it, but the knowing smile on his face and the angle of his tilted head gave the odd impression that Jackson knew what he was looking at.

His wife, Demi, dressed all in black and wearing stilettos, walked up to the image of her late husband, kissed it, stroked the surface with her bright-pink nails and whispered ‘my big boy’ before breaking down in tears.1

The sound of her distress was the only emotion on show at the strangely low-key event at South Park Cemetery on the outskirts of Boksburg on 10 May 2010. Jackson’s grave was a few metres away from apartheid struggle hero Chris Hani.

Then a gust of wind blew The Don down. Shards of shattered glass went skidding across the dry brown grass and into the grave. Jackson’s brother Costa chuckled, ‘At least he went out with a bang.’2

It was a strange event. The family arrived in a Hummer limousine and, if you looked closely, the black suits of the businessmen were Gucci and other expensive labels.

Hanging at the back were women with pale skins, puffing on cigarettes – the Teazers girls, one had to assume. They said not a word, some were clutching supermarket flowers. They left on a bus that had been laid on for them.

Jackson’s family threw dirt and yellow rose petals onto the casket. Following Greek Orthodox tradition, bottles of olive oil and red wine were poured into the open grave, followed by a Teazers shirt. The four corners of a Greek flag were held by Demi, Jackson’s two sons, Manoli and Julian, and his daughter, Samantha, who placed the flag on the red mahogany coffin.

Vincent Marino, a friend of Jackson for 35 years, gave the eulogy. ‘We all know that Lolly was a rough diamond. Rough on the edges in his mannerism, speech and action. But those who had the privilege of knowing him could see beyond the brash exterior, for within he was a man of true quality, committed to what he was responsible for’.3

He said Jackson was ‘a renegade, the anti-hero who lived by his own rules’.4 But, despite Marino’s attempt to bring some humouristic reminiscences of Jackson’s life to the event, the 200-plus crowd wasn’t biting. They just stood and stared, waiting for the whole thing to end.

Perhaps it was the horror of what had happened to the man in the casket that made them shudder. The image of how he had been killed in a spray of bullets was too graphic to shake from their thoughts.

The funeral felt as far removed from the life of this man, who had always lived large, as it could be.

Lolly Jackson started out life on the rough streets of Germiston. He saw the business opportunity of strip clubs catering for men’s fantasies, of classy girls dancing naked in front of them.

He opened his first Teazers club in Primrose, his childhood suburb, in the early 1990s. The franchise grew until there were six branches around the country. ‘The teaze without the sleaze’ was the company slogan.5

The stripping business made Jackson obscenely wealthy. He owned four properties in Bedfordview, including a huge mansion that eventually sold at auction for R9 million. Regarded as South Africa’s own playboy villa, this five-storey, seven-bedroom, five-lounge house had been the scene of many parties featuring a jacuzzi filled with plenty of flesh.

Jackson was one of only three super-rich South Africans who could afford a R14 million Swedish-built Koenigsegg CCX, the world’s fastest supercar at the time. His garage contained a fleet of the fastest, most colourful, most luxurious sports cars the world had to offer.

But his early years growing up on the mine-dumped East Rand suburbs never left him. Swinging between typical Mediterranean charm and a foul temper, he was constantly in trouble with the law. His most famous faux pas was in 2005 when he was caught travelling at 249 kilometres per hour in his Lamborghini, but claimed he was en route to church.

Jackson was not afraid of making enemies, from conservatives who balked at his risqué strip-club billboards, to competitors who accused him of sending death threats, and Ukrainian strippers arguing their contract terms with him.

Jackson once said of his competitor Andrew Phillips of The Grand: ‘That man has been sleeping on his back for ten years now because he has such a hard-on for me. I know that with fame comes pain. I’m in a business where when I do something right, it is always wrong.’6