7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

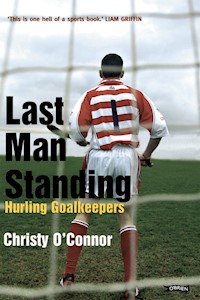

'Goalkeepers walk a tightrope between triumph and disaster...' The hurling goalkeeper must surely occupy the most precarious position on the pitch -- glorified as a saviour if their team succeeds and damned if they fail. For this book Christy O'Connor has had unique and continuous access to twelve goalkeepers over one season and tracked their experiences through the highs and lows, the celebrations and rejections, the saves and the misses, resulting in an inside story never told before. The players talk frankly about the pressures, the passion, the trauma, the disappointments and glories, the utter despair at being dropped from the team and the long road back to re-selection. The brotherhood of goalies forms a kind of inner club within the hurling community -- here we are taken into its heart and spirit as never before. Includes: Donal Óg Cusack (Cork); James McGarry (Kilkenny); Liam O'Donoghue (Galway); Brendan Cummins (Tipperary); Stevie Brenner (Waterford); Brian Mullins (Offaly); Timmy Houlihan (Limerick); Brendan McLoughlin (Dublin); Davy Fitzgerald (Clare); Graham Clarke (Down); DD Quinn (Antrim); Damien Fitzhenry (Wexford), as well as a wealth of stories and anecdotes about famous past teams and players.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Reviews

LAST MAN STANDING

‘Pick up Christy O’Connor’s book Last Man Standing. You won’t regret it.’ Irish Examiner

‘Features a series of brutally honest interviews with several of the best hurling goal keepers in the game, and should be made mandatory reading for every GAA fan in the country. Not just because of its style and content, both of which are top class, but because of what it reveals.’ Irish Examiner

‘One of the best GAA publications ever released. A perfect book for GAA fans.’ Irish Daily Star

‘As good as it gets in the GAA genre.’ Munster Express

‘O’Connor offers the reader unrivalled insight into the lives of people such as Fitzgerald, Donal Óg Cusack, Damien Fitzhenry and James McGarry. Carries some fascinating accounts about what it takes to become the best in your field and what it’s like to win and lose in the Championship.’ Irish News

‘It doesn’t come as a huge surprise to learn that [Seán Óg Ó hAilpín] is close to Donal Óg Cusack, a highly-motivated figure like himself. Insights into Cusack’s obsessive nature are contained in Christy O’Connor’s excellent book, Last Man Standing, revealing long and lonely hours spent preparing for the hurling season.’ Sunday Independent

Last Man Standing

CHRISTY O’CONNOR

DEDICATED TO MY PARENTS

TOM AND JOAN

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It would not have been possible to write this book without the assistance and access granted to me by the twelve hurling championship goalkeepers. Every single one of them could not have been more helpful and giving of their time and their loyalty and honesty is more appreciated than they will ever know. Some of them are friends who I have known for a long time, while others are people who I have got to know really well, but all of them are players I have always admired and respected.

I also owe a huge debt of gratitude to all the other people who agreed to be interviewed for this book. Due to restrictions, some people who were very generous with their time have not appeared in this book, but I would like to thank everyone who spoke to me.

This book was definitely the most rewarding and enjoyable project of my career but it was made even more enjoyable by the fact that my fiancée, Olivia, was there to accompany me during most of the matches and to share the experiences. She was the one constant for me and it is great to be able to look back and remember the special times we had on the terraces all summer.

Kieran Shannon has been a great friend to me, both as a journalist and as a person. He is someone I have learned a lot from as a journalist and he has always been very helpful during my career. Damian Lawlor, Aoife de Paor and Michael Foley are three other journalists who have always been very supportive to me as well and I would like to take this opportunity to thank them too.

I would also like to extend my gratitude to Sportsfile, and especially to Damien Eagers, to Gearóid in The O’Brien Press and to Liam Griffin. I would also like to thank Seán, Donal, Joe, Lorcan, Patsy and Claire for their friendship and to extend my thanks in particular to Eoin and Fran for all their support during the writing of this book. I would also like to say a big thanks to Derek, for helping me to come up with the title.

The final word goes to my family. My brother James has brought great pride and honour to our family: he and my younger brother John and my two sisters, Sheila and Claire, have always been very special people in my life. Finally, this book is dedicated to my parents, Tom and Joan, the two people in this world who have had the greatest influence on me as a person.

Christy O’Connor, Ennis, July 2005

CONTENTS

Reviews

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgement

Foreword

1. JUST DO IT

2. HOLE IN MY SOUL

3. RUSSIAN ROULETTE

4. COMMANDO REGIME

5. WHAT DRIVES YOU ON CAN DRIVE YOU MAD

6. ON THE EDGE

7. THE CAROUSEL

8. TOO HIGH A PRICE

9. WHAT COULD BE BETTER THAN THIS?

10. LIKE FATHER, LIKE SONS

11. MUNSTER MADNESS

12. FORGOTTEN WARRIORS

13. DAVID AND GOLIATH

14. BLACK AND AMBER AMBUSH

15. BLUE SUNDAY

16. ULTIMATE PAIN AND ULTIMATE GLORY

17. THREE GOALS, ONE TARGET

18. WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE

19. DARK FORCES

20. NO QUARTER GIVEN

21. HARD LESSONS

22. THE GREATEST CRAIC OF ALL TIME

23. THE SILENT WARRIOR

24. REBEL YELL

25. TRY WALKING IN MY SHOES

26. ALL OR NOTHING

27. EPILOGUE

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

Other Books

FOREWORD

When Christy O’Connor first asked me to read this book, I didn’t really know what to expect from it. I knew it would be a good read but I didn’t expect to be blown away like I was. This is one hell of a sports book.

I think anyone who reads this book will have their views on goalkeeping and goalkeepers altered forever. Only a goalkeeper could have written this book but he had to be a particular kind of keeper. He had to have lived, not at the very top, but within touching distance of it. He had to have lived there to really understand.

Christy O’Connor lived for many years in the shadow of Clare’s Davy Fitzgerald, one of the greatest and most driven goalkeepers the game of hurling has ever known.

Christy has a broad, deep and genuine passion for the game of hurling that very few people possess. The trust, understanding and respect he has earned from his fellow goalkeepers has enabled him to breach the inner sanctum of the GAA world for the first time ever. It offers a fascinating insight into that world.

It is a fantastic read because Christy also has the combined gift that the goalkeepers, whose stories he tells, do not have: the gift of the writer and the storyteller.

This book is of great value and it will help rid some men of their demons. It should also teach us to stop demonising these exceptional, courageous and often lonely souls, who have the guts to be the ‘Last Man Standing’.

Liam Griffin, Wexford, June 2005

JUST DO IT

Monday morning 5 January 2004, it’s cold and dank and you can almost feel the gloom of depression hanging in the air as people head back to work after the Christmas break. At 6.01am, Donal Óg Cusack’s alarm goes off in his house in Cloyne. He knows what’s ahead of him so he has already prepared the night before. His gear is laid out across a chair in the corner of the room and his work clothes are already packed away in his bag. At 6.15am, he’s out the door. Time to purge the guilt.

He heads off for work in De Puy Johnson and Johnson in Ringaskiddy. It takes him forty minutes to get there and when he arrives, he heads straight to the gym, already suited up and ready for action. He works in the facilities department of the plant and looks after the company gym, so he lets himself in. There’s rarely anyone ever there at that hour of the morning and there certainly isn’t anybody present this morning. He likes the silence of working alone and he goes about his business for an hour before he starts work.

Cusack begins with a run, then some stretching before concentrating on core exercises. It’s not easy this morning but he banishes any thoughts of neglect and punishes his muscles until they threaten to desert him. He completed this routine every day for six weeks before Christmas before he took a break. It’s time to deposit more fuel in the tank now before the Cork panel heads off to Vietnam for their team holiday on Thursday. After that, this is a ritual he’s determined not to break.

Even now, with over six weeks of hard work behind him, which was only briefly punctuated by some mild Christmas excess, Cusack doesn’t feel that fit. The rest of the Cork panel, especially Timmy McCarthy, are always taking the piss out of him about his bowlegs that are always hopping off one another. The only response he has for them is that if he had Seán Óg Ó hAilpín’s gazelle-type limbs, or if he didn’t have that dragging, consistent pain inside his right knee all the way up through his groin, he’d leave them all for dust in his vapour trail.

Cusack probably does that bit extra, not because he has to, but because of who he is. He is a goalkeeper. A hurling goalkeeper. Although nearly all players train on their own at one stage or another, goalkeepers do it more often than most others because they have to get accustomed to being alone when it matters. Of course they train with the team but they do more training, specific to their needs, alone. They can work and work on the technicalities they need to master, and they do, but no amount of training can prepare you to be alone at the death. Or to learn how to take the blame. Goalkeepers learn to be lone-minded and are familiar with such a frame of mind. They have to be because of the position they play in. Disappointment is one of the most fundamental emotions in sport and goalkeepers are the natural focus for it because they walk a tightrope between triumph and disaster. In Cusack’s position, calmness is the only means of survival and he has depended on it plenty of times in the past. Especially in the last year and a half.

On the night after Cork beat Wexford in the previous year’s All-Ireland semi-final replay, Cusack got a taxi home to Cloyne after a night’s drinking with the squad in Cork city.

Before long, the talk drifted to hurling and that day’s other All-Ireland semi-final between Kilkenny and Tipperary. The taxi-driver honed in on Brendan Cummins’ outstanding display, and without knowing who his passenger was, used it as a stick to beat Cusack with. He told him that if Cork had a keeper half as good as Cummins, they wouldn’t have needed a replay to beat Wexford. Cusack agreed with him, and let him continue with his stream of invective.

The vitriol rolled off his tongue for nearly twenty minutes. Cusack urged him on, agreeing with everything he said about how poor the Cork keeper was in an attempt to see how much poison he could extract. By the time they got to Cloyne, the air was septic with it. Cusack paid him, got out and then spotted a friend across the road who was locking his car. ‘What’s my name, Jamesie?’ he asked his friend. ‘Donal Óg,’ his friend replied with a bemused look. ‘Donal Óg who?’ ‘Donal Óg Cusack.’ The Cork hurling goalkeeper just turned to the taxi-driver and introduced himself. He left it at that and walked in home.

He knows the knives are out for him. A lot of people in the county blame him for losing the 2003 All-Ireland final against Kilkenny. Martin Comerford’s goal with five minutes to go plunged a dagger into Cork’s hearts and most of the public felt it was a ball that should have been stopped. Even though Comerford was inside the 14-metre line, Cusack was still beaten at his near post.

Comerford didn’t strike it well, but there was plenty of deception concealed in the shot. It hopped off the ground and spun past Cusack. It was one of those balls that a keeper almost watches going past him in slow motion. Every keeper feels a shot like that should be saved, but it’s extremely difficult to judge the flight of the ball when it kicks off the turf. Especially with the new sliotar on that Croke Park sod that’s like concrete. Everyone might blame him, but he doesn’t blame himself. He firmly believes that but he’s standing up for himself because nobody else will.

He has to be big now because there is a chasing pack on his tail. Paul Morrissey has been playing well with Newtownshandrum while Martin Coleman was solid last season with the Under-21s. All summer the public had been building a case against Cusack, but after the All-Ireland they didn’t have to look too far for hard evidence to corroborate their view that he wasn’t good enough to play for Cork anymore.

He was captain of Cloyne last year and they reached the semi-final of the Cork championship for the first time in their history. Even though they were facing the champions, Blackrock, they felt their time had come. They trained like US Navy Seals and Cusack became the focal point for that fanatical ambition. Before the quarter-final, seven of the panel announced their plans to take a sun holiday. They would be home in time for the match but Cusack told them he didn’t want them to go. A few home truths were spelled out. In the end, six cancelled the holiday and the guy who did go came home on the Thursday before the game.

On the night before the semi-final, Cusack got nailed with a job at work. It had been scheduled for three months in advance, he had committed himself to it and he wasn’t going to break his word. He would still be in bed early and focussed for the game the following day.

On the night, the job consisted of closing 2.500 amp circuit breakers that feed the power into the Johnson and Johnson plant. It involved more hand movement than he anticipated but he still thought nothing of it. He went home, got a good night’s sleep and got up ready the next morning to lead his team into history.

Out on the pitch beforehand, he did a full half an hour warm-up with the rest of the squad. He had worn a tracksuit in the warm-up but he took it off just before the game began. He was wearing a short-sleeved jersey and his hands began getting cold and stiff as the sweat was cooling off his body. Ten minutes into the game, he called Seán Motherway, the Cloyne subkeeper, and instructed him to go to the corner-flag and drop a few balls into him. He wanted to check if it was just the cold or whether it was the effects from the previous evening’s toil. Cloyne were facing into a stiff breeze and he wanted his handling to be spot-on.

A couple of minutes later, a ball was launched from the Blackrock half-back line and it carried in the breeze. In an instant, it was dropping down on top of Cusack.

Bodies were gathering around him, he should have batted it away, but instinct took over. He tried to grab it, the ball broke off his hand and sneaked inside the far post. Cloyne lost by two points.

If they’d won, they felt they would have rattled Newtownshandrum in the final. A Munster club title could possibly have been bagged and Cusack would have been nominated Cork captain this season. If you thought his head was wrecked before, it felt ten times worse after that incident.

‘There still isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about those two games,’ said Cusack. ‘When I think of those two goals, it’s like pure torture for me. Even now, it just rips me apart thinking about it. That Kilkenny goal still constantly flashes into my mind but it’s not as bad now as what it was. It only comes into my mind now about once a day. It just breaks my heart and you’d wonder about packing it all in. But I’m after deciding now to go hell for leather and do my best again this year. And after that, I’ll think about it again.’

On Thursday 8 January, the Cork squad flew to Vietnam for their holiday. When they arrived in Ho Chi Minh City, Donal O’Grady left Cusack, Seán Óg Ó hAilpín and Joe Deane in charge of organising collective training. On their first day out there, Cusack and Ó hAilpín went off looking for a field for thirty guys to train in. Tom Kenny, Paul Tierney and Adrian Coughlan joined them.

Just one hundred metres down the road from their own hotel in the centre of Saigon, they spotted a field adjacent to another hotel that looked perfect for their requirements. They asked security in the hotel about the possibility of using the field, but the request wasn’t even entertained. So they set off in search of another training facility. The heat was savage and the humidity was a killer but the five of them walked roughly ten miles in their pursuit of a piece of green grass. It was torture but they never relented.

They checked out every backwater and hick piece of territory around the town but nothing materialised. At one stage they ran into a group of English guys who wondered were they looking for some crowd to take them on in a five-a-side soccer match. In the end, they failed to find something suitable and decided to take their chances with the first field. They weighed up their options and reckoned that they’d only need it for forty minutes before anyone would cop it. After half an hour of shuttle runs the following evening, the security personnel from the hotel arrived out and cleared them. The field had served its purpose.

After the training session thirty white bodies crawled up the street suffering from near exhaustion. Some venerable old locals that were sitting out in the street looked on in amazement. Some of them had that stare, that perplexed look on their faces that suggested that perhaps time had just played a trick on their minds and a batch of US marines were returning from a training camp without their armoury!

When the squad flew east to China Beach a week later, it was like landing in paradise for Cusack and the commando wing of the panel. Their hotel backed right onto the beach so their training ground was in their back yard. On the first day there they decided to go for a three-mile run in the sand. They mapped it out but they didn’t know what they were letting themselves in for. The heat was ridiculous and the sand was sticky but the competition was even worse. They all dogged it out.

After that, if they didn’t train they played soccer amongst themselves almost every day, picking the teams on the basis of the country lads versus the city boys. The games were never less than ultra-competitive. At one stage, Sean Óg Ó hAilpín called the city fellas into a huddle after getting a hiding. The country lads were sewing it into them, telling them they couldn’t win a game unless it was down in Páirc Uí Chaoímh. It was like a red rag to a bull with Ó hAilpín. ‘Have ye any pride in Cork city?’ he asked them. Thousands of miles from home and O hAilpin couldn’t let it go.

When they drank, they drank, but Cusack never wanted the holiday to be an alcoholic haze. One morning, Ó hAilpín called for him at 6.55am. They went down to the gym and did an hour and a half session, before heading to the beach for an hour’s hurling. When Cusack went on his first holiday with the Cork seniors after they won the 1998 National League title, Brian Corcoran told him that the fellas who didn’t bring their hurleys would spend the week asking the fellas that did for a loan of them. Cusack has often quoted him since and most fellas brought their sticks.

After the hurling session, Cusack and Ó hAilpín went to the pool for a dip, had their breakfast and then went for a lie-down. By 11am they were back on the beach again for another soccer game. On the beach that day, Cusack really felt that the bond between the players had cemented even more since the holiday began. Their bond has been made tighter from the hurt of last year. They’re all still hurting. Badly.

They had Kilkenny on the ropes during the second half of the 2003 All-Ireland final but they just couldn’t land the punch to knock them on the canvas. Comerford’s goal was the sucker punch that flattened them instead and they couldn’t recover. Thousands of miles from home, the memory of that loss and the mental inquisitions over the goal are still eating Cusack up. Eating him.

‘Every day of the holidays, I thought about the last two games I played last year,’ said Cusack. ‘I just didn’t feel right. Personally I didn’t know whether to go drinking or training and I got caught between the two of them. Between training with Seán Óg in the morning and then going drinking with some of the other lads, I nearly fucking killed myself.’

The rest of them are still trying to rid themselves of the bad memories, the missed chances, and the lost opportunity. They’re being positive about it all though. A couple of nights after the final, the squad was drinking in a lock-in at a city bar when a card game started up. John Gardiner was at the bar and one of the card players asked him if he wanted to join the game. Gardiner inquired what they were playing when someone said it was a game of 45. Gardiner told him that he didn’t play 45, and he hardly had the words out of his mouth when some wisecrack told him that he couldn’t hit 45s either. The painful memories of Gardiner’s missed frees in the final were washed away momentarily by the laughter.

‘Even though we’re still fairly young, we’re after seeing a lot of shit,’ said Cusack. ‘I don’t think any other group gets on as well as we do, there’s no fighting or anything and we all stick up for one another.’

Even though he’s still only twenty six, this year is Cusack’s eighth year on the panel, and he hopes it will be his sixth season as first choice keeper. He isn’t the oldest member on the panel, or the team captain, or the best player, but in the Cork squad there is no influence greater than his. Brian Corcoran, Mark Landers, Fergal Ryan and Kevin Murray have all drifted away in the last couple of years and Cusack’s presence has filled the vacuum.

He is one of their chief leaders now. Even though he had just lost an All-Ireland final and had conceded a goal as a result of which most people blamed him for losing the match the previous September, when the Cork players gathered in a huddle after the presentation, one voice dominated the discussion. Cusack could be spotted in the middle of the huddle, waving his finger and still laying down the law.

‘I just remember the stadium being practically empty. Even though the presentation was just over, the place was deserted. I remember Mickey (O’Connell) with his nose bust and it was all just pure misery. I remember being so sad for the boys and saying that whatever we have to do over the winter, we have to get back here. Whatever had to be done, whatever cost it would be to ourselves.’

Everyone within the squad knows this guy has serious balls anyway. When the Cork hurlers went on strike two years before, Cusack was their leader and their median point. He was the player who went on Cork’s 96FM and claimed that the County Board was being run by a crowd of yes men who were totally oblivious to the needs of the players. The players put their necks on the line with their subsequent strike but the guillotine was always perilously dangling over his head.

He knew he had set himself up but he did it for the good of the Cork players, with no thought of the potential damage it could do to himself. He didn’t get that fanaticism from just anywhere. Eighty-three years ago, Christy Ring was born in a house which used to be two doors up from where Cusack grew up in the middle of Cloyne village. That house is levelled now, its site occupied by a statue of the greatest hurler that ever lived.

When Cusack was buying a house last year, there was only one place he had in mind. Ring’s father and Cusack’s great grandfather were brothers and the gable end of Cusack’s new house is just ten yards from the Ring statue created by the Breton sculptor Yann Goulet. Just behind that is the Cloyne field where Ring’s genius was forged and where the young goalkeeper went about perfecting his game as a child in the crucible of practice.

Home.

The holiday party flew back into Cork on 24 January and four days later they realized the holiday was really over. When they gathered in Carrigtwohill for training, it was minus 2 degrees. They knew it was freezing because they could see the frost settling on top of the training cones. Cusack normally spends part of every training session with the other keepers but Morrissey and Coleman weren’t there tonight so he ground his teeth and dogged it out. He has to dig in because he knows the knives are being sharpened for him around the county.

Over Christmas, he was in town with Diarmuid O’Sullivan and O’Sullivan’s girlfriend Gráinne. They were in Reardons’ and Cusack was afraid of losing his jacket so he got the keys of Gráinne’s car and went out to deposit the jacket. Just a few yards outside the pub, he met a gang of seven fellas coming against him. They recognised him straightaway and, with force of numbers, rounded on him.

‘You’re fucking useless Cusack!’ they roared at him. ‘You bollocks, you cost us the All-Ireland!’

It saddened him that people he didn’t know could be so callous but he’ll always be ready for that type of abuse. He’s had plenty of time to condition himself for it. Just as long as he is ready for the fight to hold onto his place.

‘It’s a big year for Donal Óg and he knows himself now that he’s going to come under pressure,’ said Ger Cunningham, who Cusack took over from in 1999 after eighteen years as Cork’s first-choice keeper. ‘I know that the selectors are going to give people chances this year and maybe the test will really come if they give Martin Coleman, Paul Morrissey or Anthony Nash a chance. If that happens, how will he react in that situation? These things kind of go in cycles and if he gets over this period and gets established again, he’ll be fine.

‘For now he knows the pressure is there and sometimes that can be a good thing or a bad thing. People buckle under pressure or they react to it. But he certainly won’t be doing any less training than what he was doing because he’s such a driven goalkeeper. He’s so focussed and is so attentive to detail. That won’t change but I’d maybe look at some of his training methods. That’s just a personal opinion but Ogie will know how he’s going. He’s very independent. He’s his own man.’

In January 2003, Cusack wrote down his three goals for the year ahead on a piece of paper. When he looked at them again a couple of weeks ago, he didn’t change any of them because he hadn’t met his targets or achieved those goals. He wanted to be as fit as he possibly could and he doesn’t think he reached that standard. He had hoped to become the best goalkeeper in the country and he knows he fell a long way short of that target. And he wanted to do everything possible to help Cork win an All-Ireland. That is what’s driving him on now.

At 9.30pm after training, Cusack sat into his car and drove home to Cloyne. The pain has returned in his leg, as it does after every hard training session. That dragging pain that crucifies him when he gets into the car. When he arrived in Cloyne, he hauled himself out of the vehicle and went in home. He laid out his gear again across the chair and packed his work clothes into his gearbag. The morning will soon be here and the gym will be calling him. This is it now. This is what lies ahead of him.

‘I don’t know if you get immune to this thing at all. I don’t even know how to describe my motivation for playing or going back training. I was asking myself going down in the car “why am I doing this now and why am I going to go through all this again?” There’s no description for it. It’s like as if I have to do it. It’s like as if it’s something that I just have to do.’

He’s just going to do it.

HOLE IN MY SOUL

Donal Óg Cusack may have his worries in the first week in February but at least he’s still raging against the machine. Over in Limerick, Timmy Houlihan is gone. Mowed down, like roadkill, more like. At present, he’s so far out in the wilderness that he can see the tumbleweed sweeping by him. And it hurts like nothing else.

In any other county with three All-Ireland Under-21 titles in four years, there would be no need to forensically trawl for two hundred players and herd them into practice games for six weeks before Christmas. It was a statement more than anything else from the new management that any amount of Under-21 medals didn’t give you any special rank. Houlihan appreciated that the status of being one of only six players in the county to have played in all three wins wouldn’t cut too much ice with the new management. But he didn’t expect to get axed.

He lives just seven doors down from Ollie Moran in Castletroy and they were chatting one evening in December and they both decided if they couldn’t make the first fifty, they’d pack it in. The word on the street around that time was that the management wasn’t happy with Houlihan. About a week later the axe fell on his head

The new management came up with fifty names and four goalkeepers and Houlihan’s name wasn’t amongst them. What’s more, Joe Quaid was also asked back but declined the offer. Houlihan doesn’t know that and at this stage, he’s better off. He doesn’t need any more salt rubbed into the wound.

He was heading down to Waterford to see his girlfriend Tina the Saturday before Christmas when he found out. The rest of the drive was a bit of a haze and when he arrived at Tina’s house in Lismore, he went straight upstairs. He couldn’t face her family.

‘I was speaking to Tina one day in January and she was fairly upset with Timmy because she couldn’t get through to him,’ said Ollie Moran. ‘She didn’t know what to say to him. It’s Timmy’s whole life. His life revolved around hurling and playing for Limerick. When something like that is taken from you, you don’t know what to do.’

Christmas was a bit of blur for Houlihan. The week afterwards, there was an intensive weekend of training for the fifty players in the University of Limerick. Houlihan lives just down the road from the college and every night he was tearing himself up inside, wondering what the players were doing and what was being said. He felt embarrassed that he wasn’t there but he didn’t take the easy option and sink into a morass of self-pity.

‘By all accounts he’s training like mad and some people were saying that he went down to Ger Cunningham in Cork for training,’ said Joe Quaid, the keeper Houlihan took over from in 2001. ‘I’d say he’s fair pissed off but he definitely deserves to be on the panel.’

Houlihan rang Cunningham in Cork just after Christmas for a chat because he knew him from his days with the Under-21s. He tried to arrange a coaching session with him in January but Cunningham couldn’t fit him in. He’s coming to Limerick on 26 February though, and a session is planned for that afternoon.

It’s going to be tough on Houlihan to make up some of the ground that he’s lost. Especially after last summer. In the drawn Munster semi-final, Houlihan’s mistake for Paul Flynn’s third goal nearly buried Limerick. Dave Bennett drove a ball in from about forty yards, Houlihan tried to control it on his hurley but it spun off his stick and Flynn pounced on it. His mistake for Flynn’s goal in the replay was worse. Flynn angled away from three Limerick defenders and when a point seemed to be the limit of the opportunity, he drove the ball across Houlihan. It wasn’t a hard shot but Houlihan went to ground and it squirmed in under his body. Waterford won by two points.

Although a lot of people have lost faith in him, Houlihan is a far better keeper than he’s been given credit for. Although there is a kind of freemasonry of goalkeeping, where it is taken for granted that non-goalkeepers will not understand, Houlihan is regarded and rated within the inner sanctum of hurling goalkeepers.

‘If you were to go through all the goalkeepers now, I’d say Timmy Houlihan from Limerick is the most natural of them all,’ said Seamus Durack, the former Clare goalkeeper who won three All-Stars. ‘I like his style but I don’t know what’s gone wrong with him. Providing he hasn’t a major attitude problem, I think if he’s worked on he has an awful lot to offer.’

Ger Cunningham isn’t in total agreement with Durack just yet. ‘I think he’s got a lot of work ahead of him. Timmy is very strong on one side and if he’s honest, he’d tell you his weakness is on his left side. He may not say that to me but I’d expect him to. Still, it’s a brave call to drop him. You’d wonder why they’re doing it but they obviously must have doubts about Timmy.’

Donal Óg Cusack reckons he has an idea where the real problem lies. ‘Timmy has something, he has it as a keeper but his nerve could be gone. That’s what it looks like to me anyway. And the poor old devil, I know what it’s like, it’s a terrible situation to be in.’

Houlihan admits his confidence is on the floor but he doesn’t think he’s lost that edge, that concrete belief that he needs as a base to survive as a goalkeeper.

‘I wouldn’t say my nerve is gone. After the Wexford game (All-Ireland quarter-final 2001), my confidence was totally gone. That was the nail in my coffin and that affected me for ages. Ages. My confidence in general was gone. I suppose my confidence was low after last year as well and it affected me. But I wouldn’t say my nerve is gone. It’s probably not what it should be but it’s not gone.’

He has no option now but to go back to basics and re-evaluate where he stands as a goalkeeper. The hard questions have to be asked. Did he work hard enough? Did it go to his head? Has he been coached properly and if he hasn’t, what’s he going to do about it?

‘To be totally honest about it, I definitely didn’t work on my game over the last few years as much as I should have. I know I can’t be making excuses but maybe a bit more guidance wouldn’t have gone astray either. I never did any specialist training and maybe that affected my attitude, in that I got a bit casual by not concentrating more on what I should have been doing. It’s a specialist position and you have to be coached. I haven’t been coached since I started hurling at eight years of age but it’s something I aim to rectify this year.’

When he first emerged on the scene as a minor on the senior team for the 2000 League campaign, Houlihan looked like the complete keeper. Solid, good shot-stopper, cocky and a diamond puckout to boot. When the Clare hurler David Forde played with him in UL, he used to say that Houlihan was so accurate with his puckout that ‘he’d put it into your eye’.

He had everything and when Joe Quaid packed up after the 2000 campaign, it seemed that Houlihan would be Limerick keeper for as long as he wanted.

When Joe Quaid was the same age as Timmy Houlihan is in February 2004, he had yet to make his championship debut or even get a decent run in the League. He did his time but that time has passed now. Although he was asked back at Christmas, Quaid had made his mind up to quit inter-county hurling after damaging his shoulder last February.

‘I’m a great keeper since I gave it up,’ he said. ‘All it takes is your man in goals to play a few bad games and you become a hero again.’

Although Quaid returned to play championship in 2002, his edge was gone two years earlier. By that stage, shots were passing him that he would have stopped between his teeth years earlier. When he was in his prime between 1994 and 1997, Quaid was one of the greatest shot-stopping goalkeepers in the history of hurling. He fell down in other departments of his game that meant he didn’t deserve to be rated amongst the Greats. Nor did he have the longevity associated with his career that grants that status. But in terms of classic shot-stopping, Quaid was that good.

He always had trouble with his flexibility and as his career progressed, that slowed his reactions down. He always had dodgy groins and he ended up having two knee operations. A few extra pounds began to cling to his hips with every passing year too and that did for him as well. His body fat ratio in 1994 was 9.6%. In 2003 it was 20.4%.

In the latter years of his career, he was only a shell of the goalkeeper he once was. He’d still pull off the odd outstanding save but his reactions were slower, his clearances terrible and his puckout was gone to the dogs.

It is easy though, to pinpoint the exact moment when his career hit the downward curve. When Limerick played Laois in a League game in Kilmallock in 1997, Quaid hit a wall that buried him. Physically he knew it but he never realised that he was also deeply affected psychologically by the events of that day.

It all began when David Cuddy struck a rocket of a penalty that bounced off the ground and Quaid got his body behind it. He knew it had hit him but he didn’t know where. The ball spilled loose and as he was trying to scramble it away, the pain kicked in and he collapsed in a heap. He knew then that the ball had struck him in the testicles. He played on but when the pain got worse fifteen minutes into the second half, he signalled to the management to take him off. They refused to do so.

He was almost afraid to look inside his togs after the game because the swelling had expanded his underpants. The minute the team-doctor saw his testicles, he was ordered to go straight to Limerick Regional Hospital. The swelling had become so enlarged at that stage that Quaid couldn’t close up his jeans. His girlfriend Majella drove him to hospital but on the way back into the city, hunger got the better of him and he stopped off at Supermacs. The minute he was attended to by a doctor they wanted to operate straightaway. But Quaid had scuppered that plan with a Big Mac, fries and a milkshake.

Quaid had no option but to sit it out and wait for the operation. When he got to the theatre late that night, a nurse recognised him and just as he was about to get knocked out with an anaesthetic, he signed an autograph for her son.

‘After it happened, I said to someone that I looked out over the back wall in Kilmallock to see if the two of them were gone, but I was hoping it wasn’t that bad. Just before I was put out for the operation, I asked the nurse what the story was. She said “I don’t know.” But I knew well from her reaction and I said to myself “there’s one of them gone anyway.”’

His right testicle had exploded on impact from the force of the ball and the surgeon had to remove half of Quaid’s testicle. When the doctor arrived down to talk to him the following morning, Quaid was stuck into a newspaper reading the match report from the previous day. The doctor asked him if he wanted counselling but all Quaid was worried about was getting his head and his body right for the Waterford game in six weeks time.

He wasn’t able to return to training for four weeks and then on his first night back, it appeared that someone had put a contract out on his crotch. During a training game, TJ Ryan came through and unleashed a rocket of a shot which hit Quaid straight between the legs. Everyone threw their eyes up to heaven but Quaid was wearing a jockstrap with a guard and the ball flew thirty yards back out the field.

‘I just got up and said to Ryan “Jaysus, that implant is some yoke.”’

He wasn’t fit enough to line out against Waterford in the Munster quarter-final in May but he was back for the semi-final against Tipp in mid-June. The match weighed heavily on his mind for a few days beforehand but it wasn’t the only thing that occupied his thoughts. ‘At that stage I had the most famous testicle in the country.’ He knew what was coming.

As he made his way down to the Killinan end goal in Thurles for the second half, he could sense the storm brewing on the terrace. Ten minutes into the half, a cluster of Tipp fans started into a chorus of a song they had made up that went to the tune of the Go West number from Village People. ‘JOE QUAID, ONLY HAS ONE BALL, JOE QUAID, ONLY HAS ONE BALL!’ Ten minutes later when another break came in play, the songwriters had managed to teach the rest of the terrace their new song and the whole crowd were belting it out at the top of their voices.

The umpires looked at Quaid sympathetically, but all he could do was laugh. The game was gone from Limerick and there was no point throwing more petrol on the flames behind him. Quaid decided to play his party piece. He turned around to the terrace, jumped up like Batman and grabbed his crotch on the way down. Immediately the singing stopped, the crowd universally clapped him and that was the end of it. Respect.

‘While the match was going on I was actually whistling the tune of it to myself but I knew if I turned around and gave them the finger, they’d have been enough songs made up about me to enter the Eurovision. I could hear the bastards up the back trying to start it up again a few minutes later but I could hear guys down the front roaring back telling them to leave me alone.’

Although Limerick went on to win the League in October, that was effectively the end of the road for that Limerick team that had been to two All-Ireland finals in the previous three years. Cork blew them away in the following year’s championship and then Eamonn Cregan took a wrecking ball to the side that Tom Ryan built. The reconstruction was slow and painful but Quaid’s form had already begun to fall in tandem with the team’s fortunes.

‘I never played a good game for Limerick after that incident. To be honest about it, I probably never had the same confidence again afterwards. When I was at the top of my game, I used to have lumps taken out of me and some of my best saves were made with my body from throwing myself at the ball. When we played Waterford in 1999, Paul Flynn came in with a ball and I turned my arse to it. The ball ended up in the net. Before I’d have thrown myself at it and probably kept it out.’

Even though he played senior hurling for Limerick for eight years, he only had four years at the top of his game. He has two Munster SHC medals and two All-Stars to show for that timespan but no All-Ireland medal. And what’s worse, he knows he is still seen by the a great deal of the hurling public as the fall-guy for costing Limerick one All-Ireland and playing a big part in wrecking the second attempt as well.

‘A lot of people around Limerick still blame me for losing the two All-Irelands and fellas have said that to me. Sure I’ve heard all the jokes that were out about me, especially after ’94. “What’s the difference between Cinderella and Joe Quaid? Cinderella got to the ball.” “What’s the difference between Joe Quaid and a turnstile? A turnstile only lets in one at a time.” You just have to laugh at some of that stuff.’

In the 1994 All-Ireland final, Limerick were five points up with five minutes to play when Johnny Dooley stood over a 20-metre free. There were six players on the Limerick goal-line, Dooley didn’t strike it as well as he’d hoped to but it still went in. That was the score that started an avalanche but many people believe that it was Quaid who rolled the snowball off the top of the hill.

He picked the ball out of the back of the net, walked behind the goals and spotted Ger Hegarty on his own near the sideline halfway out the field. He landed the ball into Hegarty’s hand, but he turned into a shoulder charge and the ball slipped from his grasp. Johnny Pilkington drove it in behind the Limerick full-back line and Pat O’Connor stole in and let fly. Bang! Game effectively over.

‘The one thing I took responsibility for that day was the lining of the goals for Johnny Dooley’s free,’ said Quaid. ‘There were six inside instead of five and I had my angles wrong. The puckout theory for the next goal is complete rubbish. I’ve looked at it again and I’ve timed it and that puckout was hit out the same amount of time I took to take every other puckout. You had apes saying that I should have pucked it out over the Hogan Stand but these were obviously guys who were playing in the 1930s when there was only one sliotar in Croke Park.

‘They were looking for someone to hang and I was the one who was hung for it.’

Two years later, in 1996, the rope was still dangling. Even though Quaid made two of the best saves ever seen in an All-Ireland final, Ger Loughnane opened the debate on the merits of his performance a week later in a newspaper interview. He said that after Wexford were reduced to fourteen men, Quaid was the one player who had time on the ball to find the loose man. But by going for length instead of accuracy, Quaid handed Wexford a 50/50 chance of winning possession.

‘That’s easy to say but you don’t realise what was going on inside my head,’ said Quaid. ‘After all the shit that had gone on in 1994 with the puckout, no way was I going to risk it again. When I saw Mark Foley calling for a ball in the second half, I thought about it for a split second and I just said to myself: “No way, it’s a hurley I have, not a scud missile launcher.”’

Quaid had to wrongly live with the blame again for losing another All-Ireland final and he knew that no matter what he did for the rest of his career, there would be no redemption from the past. No matter the hundreds of goals he had prevented, he would be cruelly remembered for two matches.

The blame was just deposited with him, without his sanction or control. He knew it would always affect his reputation and it did, but he still did his best to project the image that he was indestructible. He tried to always look in control and his demeanour gave off an aura of someone with ice in his veins. But it was really only blood.

‘People often said to me that I was one of the cockiest keepers they ever saw but if they only knew what was going on inside my head,’ said Quaid. ‘I used to be planking it. My routine in the morning before any big match was a newspaper, twenty Carrolls, into the jacks, sit down, smoke and get sick. Every morning, I’d get sick with nerves. On the Saturday before the ’94 All-Ireland, I got as sick as a dog. My routine then before the match was to get a cigarette and a lighter and go to the jacks for a crap and a smoke.

‘You ask me what made me tick, well I was thick enough for it. I remember marching behind the band on my debut against Cork in Limerick in 1994 and saying to myself “what am I doing here?” I was just absolutely shitting it and after fifteen minutes when two goals had gone past me I was saying to myself “Ah, I’m not able for this craic”. I remember leaning up against the post and looking out and it was misting and miserable and saying to myself “Ah, I want to go home”.

‘It was a complete nightmare at times. I loved the impossible situation because that was a no loss situation but I used to hate high balls dropping in. I was never standing under them thinking I was going to catch this and drive it down the field. I was thinking to myself “Holy Shit, don’t drop it.” I often wondered what went through other keepers’ heads when balls were dropping in because I know what was going through my head. (Brendan) Cummins is the best I’ve seen under a dropping ball but I was never like that. If I saw a ball going over the crossbar, I’d be saying to myself “thanks be to God that’s not dropping in here.”

‘It was tough going. It takes a certain type of individual to play in goals and you’d always wonder why you put yourself through some of the hardship. It is hard to look back and think that I should have an All-Ireland medal, but what can you do now? Maybe if we’d won the All-Ireland in ’94, I’d have gone stone mad, turned into an alcoholic and I’d have no wife and family now.’

Inter-county hurlers often get labelled, even though nobody outside their family and friends knows anything about them. Everyone thinks they know them and what their problem is. Now that Timmy Houlihan has been mowed down, most of the opinion feels that he walked right out in front of the oncoming traffic. That he became full of shit and that it all went to his head.

‘He’s a good keeper but I heard that he doesn’t give a shite about hurling,’ said Kilkenny goalkeeper James McGarry. ‘I don’t know if it’s true but that’s what I heard.’

It’s easy to hear and make assertions in a small hurling community. When he was in UL, Houlihan’s status was legendary. Every so often his new nickname would be posted up on the college’s hurling website and another bushfire of gossip on Houlihan would rage. Some of the players reckoned that he was bringing women along to watch him training. It was complete trash but it all added to his cult status within the hurling club.

The UL players reckoned he was so image-conscious that he was going to sign a contract with the Barbie Doll brand-name and begin bringing out his own range of ‘Timmy’ dolls. The nickname ‘Timmy Hilfiger’ did the rounds for a while after he wouldn’t wear anything only ‘Tommy Hilfiger’ clothing. Then it was ‘Timmy Text-message’ because he was always on the phone. The one that stuck though, was ‘Timmy Toiletries’, because of his post-match grooming routine.

‘He’s a perfectionist by nature and that’s where all of that came from,’ said Ollie Moran, who coached the UL Fitzgibbon Cup winning team that Houlihan was part of in 2002. ‘He’d have his boots waxed and cleaned, his gear all laid out and after the match he’d step into the Calvin Klein boxers. He had every kind of deodorant, after-shave and face cream under the sun, but that wasn’t him trying to make an impression. That was just Timmy by nature and he was the same in the way he used to prepare for matches. He was just methodical.

‘When I hear people say that he deserved to be dropped because he’s arrogant, I see red. If every guy had the attitude and approach to preparation that Timmy had, Limerick would be doing a lot better than they are. Timmy must be the most misperceived and misunderstood guy you ever saw in your life. He took a fair hammering when he was dropped two years ago and he battled back. To pick four goalkeepers ahead of him now, you’d wonder was there something else to it.

‘He’s never the fifth best goalie in Limerick. All Timmy needs is reassurance. Tell him he’s a fine keeper that just needed to clean up a few things. No one could tell him that, so rather than do that they just dropped him. I was angry in a way and I think someone could have been big enough to tell him where he stood. He’s a very hard guy to get into and to get seriously talking to. I’d know him well but I’d say I’ve only hit that level with him three or four times ever, where he’s really opened up to me. He must be going through torture inside his head.’

Cusack looks at Houlihan now and tries to imagine himself in his position. The thought is unbearable but Cusack knows that he wouldn’t be put through it in Cork.

‘You’d just wonder if a fella that good has been managed properly, but the GAA falls down desperately in the department anyway. There’s no structure in a lot of places. In fairness Cork have that at the moment. Donal O’Grady has that idea of developing guys, training them and educating them. It doesn’t sound right that such a talented guy has been let go like that and just left there.’

When Moran was training UL two years ago, he knew what Houlihan needed more than anything else. Someone to put a hand around his shoulder and tell him how good he was. Reassure him, relax him and calm his nerves. Moran brought in Eamonn Meskell from his own club in Ahane and he was brilliant for Houlihan. He kept telling him he was the best keeper in Limerick and he responded to it. He was excellent in UL’s run to the title.

‘If Timmy was to ever relax, he’d be a much better keeper,’ said Moran. ‘I always felt he was playing within himself. It was almost like a burden on him sometimes and it definitely affects his performance. When you’re nervous you start going through all the negative permutations in your head and he’s so conscious of all of that.

‘His biggest fault as a goalkeeper is when he loses concentration, that manifests itself in a match when he tends to go to ground too early. (Paul) Flynn’s goal last year highlighted that, but that’s something that can be corrected very easily. It’s a small kink in his game but it’s manifesting itself in a very big way. Timmy needs very little to correct his game because he has all the natural ability in the world. Image, my arse, it’s nothing to do with that. Some people just love to slate and cut other people.

‘You see (Brendan) Cummins, Davy Fitz, (Damien) Fitzhenry, they’re all nice guys who aren’t arrogant but who are really confident fellas. They’re not obnoxious but they all know that they have it. You see Timmy then who’s equally as good as them and he’s nearly made feel ashamed that he’s talented.

‘It’s his mental game that he just has to work on. There would be nothing wrong with bringing a sports psychologist in to see him to address the problems he has. If he had a fella to do that and it worked on him, he’d be doing cartwheels inside in goals. That’s something that just has to be developed. He’s too good not to be helped out because the big danger is that he could end up on the scrapheap.’

Within the squad, the experienced players feel that they need him. ‘I think he just has to be brought back,’ said Steve McDonagh. ‘Timmy’s biggest attribute is his puckout. Hurling isn’t as much about stopping shots anymore, it’s about being able to place your puckouts. I feel we’re really missing that at the moment and he would be a big addition to our system.’

All Houlihan can do for the moment is keep on keeping on. No matter what he does anyway, he can’t change opinions and what people really think of him. And if he’s to be really honest about it, he may have given some critics a rod a few years ago that they are leathering off his back now.

‘I won’t say that it totally went to my head, but definitely the second year I was on the panel, it affected me. I remember talking to my brother Tony one night and he said that he even found it hard to talk to me. I was living in Limerick and wasn’t going home that often and I suppose I didn’t even notice it myself. That statement really opened my eyes.

‘People were saying that I was arrogant. I was always confident but you have to be when you’re playing in goals. I find it hard to put a finger on it now but it affected me and definitely affected my approach to the game. When that happens with your family, you have to take a step back and say to yourself that there’s something seriously wrong here. I had to take myself down a peg or two and realise that when things do go wrong, your family are always there for you. But that was the big turning point for me and definitely, I’m after changing in the last two years.’

It’s not as if he hasn’t been down this road before. Houlihan was dropped off the squad altogether in 2002 after Quaid returned from a year in the wilderness. It sobered him up and forced him into deep introspection.

‘I felt my attitude had changed last year. I never put in so much effort into training in the last year and a half. I was never the fittest player but maybe I’d taken the easy option at times in the past. I thought I’d turned a corner when I came back last year, but this is definitely a bigger kick in the teeth. I knew I had to improve and play better and I was going back this year to try and prove a point to everyone else. And to myself, that I was better than I had been showing. I still think I can compete with the best of them. I’m not going to say that I’m as good as Brendan Cummins because he’s just outstanding, but I definitely think I could hold my own with a lot of keepers.

‘People can think what they want of me now but I’m not going to throw in the towel and if anything this has made me stronger and more determined. I made some big mistakes in the last couple of years, but I can correct them. Without a shadow of a doubt I know I can. I just have to prove myself again, but it probably won’t happen this year. I just haven’t got that chance now.’