9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fernhurst Books Limited

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Looking back at the lives and sailing careers of some of our lifetime's finest yachtsmen, this collection of eleven original, moving accounts is just as much a celebration of the good – tales of hope, achievement and courageous spirit – as it is an account of their tragic final voyages. Included are world-renowned racers, like Eric Tabarly and Rob James, highly experienced cruisers and adventurers, like Peter Tangvald and Bill Tilman, and the notoriously ill-prepared Donald Crowhurst, as well as other famous and some less well-known sailors. Starting with the sad loss of Frank Davison and Reliance in 1949, the book concludes with the amazing last voyage of Philip Walwyn in 2015 – crossing the Atlantic single-handed in his 12 Metre yacht Kate. All of the men and women described were friends with or known to the author, Nicholas Gray, who himself competed in several short-handed long distance races, where he met and raced against many of these fascinating characters. Peppered with photographs showcasing the sailors and their yachts, this is a refreshing look at those who have helped to shape this sport's history, honouring their lives and accomplishments before detailing their tragic last voyages.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

.

.

First published in 2017 by Fernhurst Books Limited

62 Brandon Parade, Holly Walk, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, CV32 4JE, UK

Tel: +44 (0) 1926 337488 | www.fernhurstbooks.com

Copyright © 2017 Nicholas Gray

Nicholas Gray has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act,

1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a license issued by The Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The Publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-909911-55-0 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-909911-93-2 (eBook), ISBN 978-1-909911-94-9 (eBook)

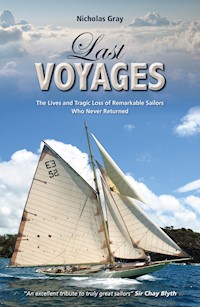

Front cover photograph: Philip Walwyn’sKatebetween the English Harbour Heads:

From the Walwyn family archive. By kind permission of Kate Walwyn, Susie Walwyn and John Halsey.

Back cover photograph: Nicholas Gray: By kind permission of Lester Barnes.

Designed by Rachel Atkins

To Josephine

“Qui vit sans follie

n’est pas aussi sage

qu’il croit”

(author unknown)

Inscription seen by Peter Tangvald

on an ashtray in his parent’s house

“Whoever lives without folly

is not as wise as he thinks”

.

Contents

Foreword

by Sir Chay Blyth

Introduction

Chapter 1

The last voyage of Ann and Frank Davison and the loss of the

Reliance

(1949)

Chapter 2

The strange last voyage of Donald Crowhurst and the trimaran

Teignmouth Electron

(1969)

Chapter 3

The life and last voyage of Mike McMullen and the loss of the trimaran

Three Cheers

(1976)

Chapter 4

The last voyage of Simon Richardson and Bill Tilman and the loss of

En Avant

in the South Atlantic (1977)

Chapter 5

The life and loss of Alain Colas and his trimaran

Manureva

(1978)

Chapter 6

The last voyage and loss of the trimaran

Bucks Fizz

and her entire crew in the Fastnet Race of 1979

Chapter 7

The life, last voyage and loss of Angus Primrose and

Demon of Hamble

(1980)

Chapter 8

The life and last voyage of Rob James on board his trimaran

Colt Cars GB

(1983)

Chapter 9

The life, loves and last voyages of Peter Tangvald on board

L’Artemis

and his son Thomas on board

Oasis

(1991 and 2014)

Chapter 10

The life and last voyage of Eric Tabarly on board his yacht

Pen Duick

(1998)

Chapter 11

The extraordinary life and last voyage of Philip Walwyn on board his 12 Metre yacht

Kate

(2015)

Afterword

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

.

Foreword

by Sir Chay Blyth

No sailor ever embarks on a last voyage. They set out with hopes and aspirations; excitement and perhaps a little apprehension; the horizon offering many possibilities. None of the voyages described in this book were undertaken with the intention of it being the last. But these remarkable sailors all lost their lives at sea, many alone, and many of whose bodies were never returned to land.

In few cases does tragedy occur right away. Often it is significantly into the voyage, in many cases near its completion, when something goes wrong and disaster strikes. Whether through a medical emergency… bad weather… a fault with the vessel… or merely slipping overboard… all of these voyages were their last; although we cannot always be certain exactly what happened.

Nicholas Gray describes, with an elegance and sympathy rightfully deserved by such characters, the lives, sailing careers and final voyages of a number of well-known yachtsmen, all friends of or known to him. He gives a wonderful insight into the people behind the headlines and their lives before the tragedies. This is an excellent tribute to truly great sailors.

Many of those described in this book I have had the pleasure to sail with or compete against. Reading their stories brings them to life again, allowing one to look back and remember their achievements, and enabling their legacy to live on beyond their momentous final voyage.

Last Voyagesis a superb read. I thoroughly recommend it for anyone, like me, with a love of the sea or an admiration of those who have the courage to contend with this mighty force of nature.

.

Introduction

Some years ago whilst on a climbing trip in North Wales, one member of our party said that he was giving up climbing as he knew too many people who had died on the mountains.

I mulled this over during the rest of that weekend. Whilst I had never climbed outside the United Kingdom, I had met or come across several famous climbers in the hills of Scotland and North Wales and I knew that some of them were no longer with us. This was perhaps inevitable as, with every passing year, climbers were taking more and more risks on more and more extreme climbs in more and more severe weather.

Later, lying comfortably in my sleeping bag with rain hammering on the tent and a cold wind swirling around outside, my thoughts turned to those friends and acquaintances I knew in the sailing world who had been lost at sea and who had never returned from their last voyage. Some had been lost whilst alone, some had left a shocked crew behind to endeavour to continue the voyage and bring their vessel home and some had gone down with the loss of the boat and all its crew. Many of these people were household names who had achieved great success on the oceans of the world, others were merely doing what they liked best – sailing a small boat without fuss across the world’s oceans.

Soon after that trip to North Wales I decided to write about some of the sailors who I had known and who had been lost at sea. Some had been good friends. Others I had met in passing or whilst taking part in races or regattas.

I have been sailing all my life and in 1977 I first got involvedin the world of fast racing multihulls. I took part in the 1978 TwoHanded Round Britain and Ireland Race on a 35-foot trimaran,where I first met several of the people who feature in this book.Rob James was sailing with Chay Blyth in the monstrous trimaranGreat Britain IV(which I later campaigned for a season) and Irenewed a childhood friendship with Philip Walwyn who racedin his trimaranWhisky Jack, which he sold to me after the race.

Two years before that another friend, Mike McMullen, hadbeen lost in his trimaranThree Cheerswhilst taking part in the1976 Observer Single-Handed Transatlantic Race, the OSTAR.The next year, 1977, the famous mountaineer / explorer / sailorBill Tilman, with whom I had nearly sailed to Greenland in myuniversity ‘gap’ year, was lost in the South Atlantic. He was onboard the converted tugEn Avantwhich disappeared, along withits entire crew, on passage to the Falkland Islands. Tilman wascelebrating his 80th birthday by sailing to the South Atlantic onan expedition aiming to climb a mountain on Smith Island.

In 1979 I was the last person to see off the trimaranBucks Fizzas it set sail to take part in that year’s ill-fated Fastnet Race.BucksFizz, a near sister ship to the famousThree Cheers, was owned andsailed by another friend, Richard Pendred, and he and his crewwere amongst the many fatalities of that race.

The next year, 1980, the British yacht designer Angus Primroseand his boatDemon of Hamblewere lost off the South Eastcoast of the USA. A year before, I had had discussions with himabout the possibility of my building a yacht to one of his designs.

Over the years I have sailed to France to take part in severalof their multihull races and regattas, most noticeably the ‘Tropheedes Multicoques’ held annually at La Trinité-sur-Mer inBrittany. There I met many of the illustrious Frenchmen whohad developed this sport and who had achieved near ‘rock star’status in their own country. Amongst these were Alain Colas,who was lost at sea on board his world girdling trimaranManurevawhilst taking part in one of the Route de Rhum single handedraces and Eric Tabarly, the most famous of them all, who felloverboard from his beloved yachtPen Duickin 1998 and was lostwhilst sailing up the Irish Sea on passage to Scotland.

I also write about the double tragedy of Peter Tangvald, aNorwegian yachtsman whom I first met in 1959, and his sonThomas. Peter spent his whole life wandering the world’s oceansand was lost when his yacht hit a reef in the Caribbean in 1991.In 2014 his son, Thomas, was also lost at sea whilst alone onpassage from French Guiana to Brazil.

I start the book with a description of the tragic first andlast voyage, in 1949, of Frank and Ann Davison in their yachtReliance, during which Frank was lost and the boat wrecked. Annwas a friend of an old aunt of mine who, many years ago now,told me about these events.

I also recount the strange last voyage of Donald Crowhurstin his trimaranTeignmouth Electron. He wandered the waters ofthe South Atlantic whilst pretending he was hurtling around theworld via Cape Horn in pursuit of the Golden Globe Trophy forthe first person to sail alone around the world non-stop. A filmof this story,The Mercy, staring Colin Firth was released the daythis book was published.

I end the book by describing the extraordinary life of an old childhood friend, Philip Walwyn, who tragically lost his life in 2015 only 10 miles from his destination at the end of a solo transatlantic voyage on his 12 Metre yachtKate.

For obvious reasons there are few accounts of such last voyages. Often there have been no survivors to tell the story and such accounts as do exist are often mere conjecture. Whilst nowadays few sea passages end in disaster there is a poignancy about those that do, especially when a sailor is alone on the high seas and is overwhelmed by accident or stress of bad weather. The wide ocean can be a very lonely place, as can the narrow sea when tragedy strikes close to land at the end of a long voyage.

.

Chapter 1

The Last Voyage of Ann and Frank Davison and the Loss of theReliance(1949)

An ageing aunt of mine first told me about her friend Ann Davison and the tragic voyage of theReliance, which led to the loss of Ann’s husband Frank. When I was young this aunt was an exotic figure who lived alone in a mews house in South Kensington and worked at the Foreign Office. At the age of twenty, at the start of the Second World War, she had married an RAF bomber pilot. He was killed six weeks later. For the rest of the war she did something secret at Bletchley Park and later worked for, and became the lover of, Frank Birch, the head of Bletchley’s Naval Section. He was one of the people who helped crack the Enigma code. After the war she helped Frank Birch write the official history of British Signals Intelligence during the war.

My aunt Monica was one of the first women in England to own her own sailing boat. Soon after the end of World War II, she bought a series of old gaff cutters which she kept on the Helford River in Cornwall, looked after by a local boatman. One of these yachts was an old Falmouth Quay Punt calledCurlew, which later achieved fame in the hands of Tim and Pauline Carr. They spent many years on her cruising the world to far flung places including time spent on South Georgia in Antarctica.Curlewhas now ended her sailing days and is exhibited at the National Maritime Museum in Falmouth.

Monica escaped to Cornwall whenever she could get away from London. It was during one of these visits that she met Ann Davison who was preparing her boat to become the first woman to sail across the Atlantic alone in her small yachtFelicity Ann. When I was a schoolboy, Monica gave me a copy of the book Ann had written about her life with, and the death of, her husband Frank – a story which fascinated me ever after. The book, first published in 1950, was calledLast Voyageand was subtitled ‘An autobiographical account of all that led up to an illicit voyage and the outcome thereof ’. Some years later Monica gave me a copy of Ann’s next book, calledMy Ship Is So Small, describing her Atlantic trip.

Cover of Ann Davison’s book Last Voyage

Frank and Ann Davison were free spirits who first met in the years leading up to the Second World War. When he was young, Frank left England for Canada, worked as a lumberjack, panned for gold, gambled successfully on the grain market and then lost all his profits in a failing oil company. He raced motor cars and drove huskies across the Canadian snows. He sailed a small yacht single-handed back to England, where he taught himself to fly. In 1934, having got married, he took over a near derelict aerodrome on the Cheshire side of the River Mersey. There he built up a business offering charter flights, aerial photography and any thing else that came along.

Ann had been born into a family of artists in England. She went to Veterinary College determined to ‘do something with horses’, became engaged to, and then ditched, a fellow. She became obsessed with aviation. In the 1930s she was one of the very first women in England to have qualified as a commercial pilot. She eked out a living working freelance doing charter flights, mail delivery by air around the UK and whatever else she could pick up.

In 1937 Frank advertised for a pilot to fly out of Blackpool, offering joy rides to holiday makers. Ann, who was seeking a change in her life, answered the advertisement and was taken on.

Ann shared Frank’s love of variety, excitement and adventure. They had much in common and, after a while, fell in love. Frank divorced his first wife, Joy, in 1939 and that same year he and Ann were married. Sadly, Joy was killed in a flying accident the next year.

Their business prospered and Frank was full of ideas to expand further. He planned to build a make of Dutch aeroplane in the United Kingdom and hatched plans for an aerial bus route linking towns in the north west of England when the Second World War broke out.

Three days before the declaration of war the Air Ministry grounded all civilian aircraft. Then they requisitioned the aerodrome and the house in which Frank and Ann lived. The aircraft and everything else were bundled out of the hangers and stored in a nearby grandstand where the entire lot was destroyed by a fire, started by an intruder. No one in authority wanted anything to do with the situation and no proper compensation was ever agreed or paid. The RAF was not interested in Frank, he was considered too old, and nobody at that stage of the war wanted a female pilot.

So they moved on. Frank’s family had an interest in some gravel quarries in Flintshire and Frank decided to develop one of these. A contract with the Air Ministry to supply gravel for a large project in Birkenhead was signed. A large mortgage was taken out to pay for it all.

Then, as so often in Frank’s life, things began to fall apart. An exceptionally severe winter, with heavy frosts and snowfall, brought production to a halt. With no revenue coming in, mortgage payments were missed. When production started again Frank offered to pay off the arrears but the mortgage company refused these and promptly foreclosed on him.

This hit the two badly and Frank began to doubt his abilities, became bitter and withdrawn. Left with nothing but a small income from a smallholding run by Ann, they came across R M Lockley’s booksDream IslandandIsland Days, telling of his life on the island of Skokholm off the Pembrokeshire coast.

Frank thought that Lockley had hit on something and said to Ann: “That’s what I should like to do. Get to hell and gone from all this bloody turmoil and farm one of those little islands.... No bureaucratic busybodies, no ruddy argument. Not a goddam’ soul. Bliss.” So they started to look for an island.

This was not something easy to come by in the middle of a war but eventually they did find one, Inchmurrin, on Loch Lomond. They took on a tenancy, moved in, chartered a 4 ½ ton sloop in which Ann learned to sail and started a new life. They spent ten months on the island and it nearly broke their hearts. Everything which could go wrong went wrong. The goats died from eating grass infected by parasites, the geese eggs did not hatch and Frank’s bank foreclosed on a small mortgage left over from the quarry and grabbed everything in his account.

They surrendered their tenancy and moved to another island on the loch called Inchfad. This was a better proposition, despite having no electricity or plumbing. Water was drawn from the loch by bucket. They continued to raise goats and geese, which prospered, and Ann started writing and selling magazine articles. They bought an old lifeboat and an engine from the Ministry of Transport which they converted into a barge.

But, despite this relative success and being the types of people they were, they soon became restless again. Ann told Frank that she could do with some ‘real gut-stirring’ as she put it and Frank agreed. They talked of emigrating and travelling around the world but doing it slowly. One day in 1945, just after the war ended, Frank returned to the island from a business trip with a sheaf of papers – a list of yachts for sale.

By now they had developed their idea into a simple plan – get hold of a boat and take it on a slow trip around the world, stopping at the first place they came to which they liked enough in which to settle. They reckoned they needed £2,000 for a boat and £1,000 in cash. If they could sell the island they would go, if they couldn’t they would stay.

In 1946 they did find a buyer and sold the island and their livestock for a good price. They kept only their Alsatian dog and two goats, which they proposed to take with them on their boat (if it was large enough). Ann had persuaded Frank that this was not a crazy idea and reminded him that sailors used to take goats on sailing ships for a milk supply.

Ann and Frank left the island, boarded their animals with friends and started a search for a ship: a hard thing to do at that time. Most private yachts had been laid up during the war or had been requisitioned by the Navy. Others had had their lead or iron keels and other metal work removed to help the war effort. The search took them from Fort William in Scotland to the South Coast of England, to Bristol, Swansea and Ireland. They looked at a 50-foot MFV offered at £400, a Bristol Channel pilot cutter, a rusting steel schooner, a Brixham trawler, a pretty Swedish-built yawl and a Baltic trading schooner. Finally, they found a heavily-built fishing boat berthed in Fleetwood in Lancashire, namedReliance. She had been built in Fleetwood in 1903 on the lines of a yacht and named after the winner of that year’s America’s Cup.

Frank appointed Humphrey Barton, a yacht surveyor working in Jack Laurent Giles’ office in Lymington, to surveyReliance. After giving her a good going over, Barton said he thought she was sound and that Frank might make something of her. They bought her for £1,450. What they got was just a hull, a rusty engine, some bits of equipment and some old sails, but little more.

By today’s standards theReliancewas huge, 70 feet long with a beam of 18 feet and a draught of 9 feet 6 inches. She was massively built of pitch pine on oak and had once been rigged as a gaff ketch. On deck she was a grim mess with old worn out gear everywhere. Below decks she was even worse and in the engine room there was an old rusting Gardner 26VT two-cylinder diesel with compressed air starting which had been installed in 1925.

Frank and Ann moved to Fleetwood to start fitting out the old boat. At first they lived ashore then moved on board to save money. The original plan was simple: re-step and re-rig the masts, have new sails made, renew some decking and strengthen the wheelhouse. But, as anyone who has taken on the renovation of an old yacht knows only too well, things seldom work out like that.

Not only was Frank a perfectionist but, as so often happens, he became too enamoured with the boat: the amount of work expanded and everything had to be carried out to the highest quality. They started on a complete renovation of the interior. Later it was found that the engine had to be virtually rebuilt and the massive wooden bearers supporting the engine renewed. Shipwrights and engineers were engaged, sails and materials ordered. The vessel, moored alongside the town quay in full public view, became the talk of the town with much muttering from the local fishing community that maybe the new owners had taken on too much. Against this, her quality of build and her sailing abilities were well known and approved of.

Soon problems began to pile up one on top of another. Materials were hard, and sometimes impossible, to come by, costs escalated and the engine, once rebuilt, was almost impossible to start. (It took at least two people and some two hours to achieve this. First a compressor on a generator had to be run to pressurise a large air bottle. Then a blow lamp had to be aimed at the two cylinder heads to heat them until virtually red hot. When all was ready, the fly wheel had to be levered by hand with a crow bar until correctly aligned. Then a valve was opened and the engine might start. If not, the whole process had to be gone through again.)

Much of the work turned out to have been poorly done but full payment was still demanded. Debts began to mount and money began to run out. Their best shipwright deserted them and the Davison’s were forced to consider taking paying crew with them for their voyage. They tried to arrange a charter and Frank nearly pulled off a job to act as base ship for a diving film to be shot in the Pacific. Soon invoices went unpaid and writs began to fly. Ann raised some money from writing articles and from the sales of a book she wrote about their island life but this was not enough.

Then a man from the Ministry of Shipping visited them and asked searching questions of their plans. After this Frank became convinced they were being watched by local Customs officers and he was sure he saw strange men hanging around the quay from time to time. They hatched plans as to how they were to get their money out of the country. At that time the amount allowed was limited to £50 per person.

In the summer of 1948, suddenly and out of the blue, their bank demanded full repayment of its loan. They knew this could end everything but they managed to persuade the bank to give them six months to sellReliance. No buyer came forward and on Christmas Eve Frank and Ann received formal Notice of Foreclosure from the bank.

Matters dragged on over the next few months and in April they learnt thatReliancehad been placed in the hands of a shipbroker for auction. Then some people from whom Frank had borrowed £250 bought a summons against him. They had no money with which to pay and Frank and Ann knew that this was the end. They would lose a court case which would mean a writ nailed to the mast and ruination.

They played for time and got an adjournment of the summons until 17 May. Then one morning with only two weeks to go, Frank stopped what he was doing and said to Ann: “I can’t stand any more of this. Let’s clear out.... From now on the game is going to be played my way. To my rules. We will sailRelianceacross to the States, or Cuba and we will have a chance to sell her for something like her value. It’s our only chance of meeting these liabilities. And I’m damned if I am going to wait like a chicken for the axe.”

“And we shall have had a sail,” Ann said, in full agreement with Frank.

They knew they were leaving debts behind and that, once they set sail, it would be impossible to enter another port in the United Kingdom. But they were not prepared to give up their dream.

They made a plan to leave on Sunday 15 May, two days before the Court hearing and they started their preparations. To depart secretly was difficult as they still had to fuel and provision the ship. This they achieved with a great deal of subterfuge and with many silent night trips ashore. They managed to fob off officials from the Customs and the Ministry of Transport, the latter tipped off by the fuel company who provided the diesel Frank ordered. All the locals knew something was afoot.

On their chosen day they waited on board for the tide to rise sufficiently to floatReliance. They had put it about that they were only going out for engine trials. After one false start, when a vital piece of the engine broke and had to be replaced, delaying them some 48 hours, they slipped their mooring lines at high tide in the late afternoon of 17 May and motored out of the harbour.

As they motored down the channel past the fishing quays everyone stopped what they were doing and watched, in silence. No-one waved them off. The weather was dreadful and a lowering grey sky foretold strong winds to come.Reliancenegotiated a dog leg in the harbour mouth and was soon out into the estuary heading for the Lune lightship. There they met a freshening south westerly wind. Unbeknownst to them, southerly gales were forecast.