7,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 4,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WriteLife Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

This is the real stuff.

It's about the people who make the decisions on how cases are handled, the different units and bureaus in the prosecutor's office, and takes the reader into "the room where it happens," the place where decisions are made at the highest level and where policy is set.

Written from a prosecutor's standpoint, this book touches on the relevant and timely issues facing the country and law enforcement today. It deals with police and prosecutor relationships, drug legalization, the opioid crisis, and dealing with violent juvenile crime.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

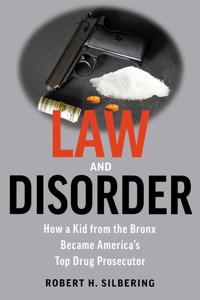

Law and Disorder: How a Kid from the Bronx Became America’s Top Drug Prosecutor

© 2024 Robert H. Silbering. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This story is told from the author’s experience and perspective.

Published in the United States by WriteLife Publishing

(An imprint of Boutique of Quality Books Publishing Company)

www.writelife.com

978-1-60808-296-4 (p)

978-1-60808-295-7 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2023951224

Book design by Robin Krauss, www.bookformatters.com

Cover design by Rebecca Lown, www.rebeccalowndesign.com

First Editor: Caleb Guard

Second Editor: Allison Itterly

PRAISE FOR LAW AND DISORDER AND ROBERT H. SILBERING

“I knew, respected and worked with Bob Silbering in the family court in the 70s. We were both prosecutors. The justice system was trying to find its legs. A mix of good judges and bad. Good lawyers and bad. Some dedicated. Some not. Bob was one of the dedicated ones. He chronicles the justice system with impeccable recall in this book. Sadly, the more things change, the more they stay the same. The system has not learned from history. Read this book and you’ll understand.”

— Judge Judy Sheindlin

“Law and Disorder chronicles Bob Silbering’s extraordinary and unparalleled career as a prosecutor for many decades successfully battling the dual plagues of rising crime and drug fueled violence and disorder that threatened to overwhelm New York City. Silbering takes you on a high-speed roller coaster ride through those turbulent and exciting times, recounting his experiences working for the legendary Manhattan DA Bob Morgenthau and then as the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for New York City as they confronted many of the crime stories that dominated the front pages of NYC’s famous tabloids. It’s a must read. You won’t be disappointed.”

— Bill Bratton, Former New York City Police Commissioner (1994-1996, 2014-2016)

“Bob Silbering had a front row seat directing the prosecution of major international drug dealers who were destroying the quality of life in New York City. His ‘low key’ style and ‘easy going’ personality allowed him to move seamlessly and effectively among the many levels of law enforcement: federal, state, and local.

Bob’s story is a New York City story where hard work, a sense of humor and determination will position you to succeed. This is a must read for everybody interested in drug enforcement and the criminal justice system in New York City.”

— Lew Rice, Former DEA Special Agent in Charge, New York Division (1997-2001)

“Law and Disorder is a must read for prosecutors and law enforcement leaders alike charged with tackling today’s most pressing and complex issues. Pursuing justice is a team sport and Bob was the quintessential coach who brought the best players together to work collaboratively and effectively to bring criminals to justice. As a former Assistant District Attorney and FBI special agent, I am forever indebted to Bob for his leadership and wisdom.”

— Michael C. McGarrity, Assistant Director Counterterrorism, FBI (Retired); Director of Counterterrorism, White House National Security Council (Retired)

To my family for all your love and support.

You’re the best!

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost I would like to thank my chief editor, advisor, and wife Shelley for all her help, patience, and support in getting this book written. She was always there when I needed her guidance and wisdom in completing the project. I also want to thank my daughter Jill and son David and their spouses Scott and Jackie for all their support and encouragement. A special thanks to Gil Reavill for helping me write and structure the book and bring all my memories and stories that went into this book to life. Without his encouragement and experience this book would never have been written.

Accuracy was very important to me in writing this book. I would like to thank the following wonderful people who helped to refresh my recollection and add details to events that occurred many years ago:

Edward Beach

Bridget Brennan

Patrick Conlon

Steven Fishner

Steven Gutstein

Judge Sterling Johnson

Gary Katz

Jose Maldonado

Mari Maloney

Chris Marzuk

Matthew Menchel

Eric Pomerantz

Jeffrey Schlanger

Judge Robert Seewald

Judge Leslie Crocker Snyder

Jerry Speziale

Ida Van Lindt

I would also like to thank Barry Marin for his technological assistance in helping me get the photo section together.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1 A Killing in Queens

Chapter 2 My Humble Beginnings

Chapter 3 My Life in Crime

Chapter 4 Cops and Robbers

Chapter 5 Criminal Court

Chapter 6 The Boss

Chapter 7 Family Court

Chapter 8 Knee-to-Knee with Evil

Chapter 9 Judges and Juries

Chapter 10 A Murder in Chelsea

Chapter 11 Bureau Chief

Chapter 12 Special Narcotics

Chapter 13 The Crack Epidemic

Chapter 14 Crisis in Washington Heights

Chapter 15 Mr. Special Prosecutor

Chapter 16 Task Force

Chapter 17 Undercover

Chapter 18 Special Investigations

Chapter 19 End of an Era

Chapter 20 Life After SNP

Chapter 21 A Look Back at My Life

A Final Word

About the Author

Bibliography

“The prosecutor has more control over life, liberty, and reputation than any other person in America.”

– Robert H. Jackson, U.S. Supreme Court Justice

CHAPTER 1

A KILLING IN QUEENS

On the early morning of February 26, 1988, a rookie NYPD officer named Edward Byrne was parked in his radio patrol car. The block of Inwood Street in South Jamaica, Queens, had become infested with drug crews selling crack, a form of purified cocaine that had the entire city in its deadly grip.

A Guyanese immigrant, who went by the single name of Arjune, lived in a gray clapboard house at Inwood Street and 107th Avenue. An upstanding citizen, he had resisted the plague of narcotics trafficking in the neighborhood. But he’d paid for his bravery, as his home had been firebombed twice. One time, he picked up a flaming Molotov cocktail and tossed it back at his attackers, severely burning his hands in the process.

Still, Arjune didn’t back down. He was set to testify against the drug lords who were threatening his life and disrupting the peace on his block.

To protect the witness, the command at the 103rd Precinct in Queens assigned round-the-clock surveillance on Arjune’s home, which was why the rookie cop was stationed on the corner of Inwood and 107th that night.

Byrne, the son of a cop, had celebrated his twenty-second birthday only four days before. Relieving Officer Nancy Stefan a little after midnight, he climbed into the driver’s seat of the marked Ford Impala squad car and battled boredom during the early morning hours of that cold, cloudy night.

Two gunmen crept up on Byrne’s radio car, acting on the orders of their boss, a drug kingpin named Howard “Pappy” Mason, who was intent on intimidating not only Arjune but also the entire NYPD.

One of the gunmen, Todd Scott, tapped on Byrne’s passenger side window. Startled, the rookie cop turned his head, instinctively placing his right hand on the duty gun in his belt.

“I’ll come around,” Todd Scott mumbled, attempting to distract Bryne.

Atthesameinstant,theothergunman,DavidMcClary,sneaked up on the driver’s side, leveled a chrome-plated .38 revolver eight inches from Byrne’s head, and fired.

The window glass shattered, sending splinters into the rookie’s face. The copper-jacketed bullet ripped into Byrne’s jaw. McClary kept shooting. Four more bullets effectively destroyed the skull of Officer Edward Byrne, tragically ending his young life.

The duo boasted about the murder as they fled from the scene.

“That shit was swift,” crowed Todd Scott.

“I seen his blue eyes,” said McClary.

I wasn’t there.

The words spoken by the murderers of Officer Edward Byrne were documented from a trial transcript. The facts of the crime were established only in its aftermath in a court of law. This is my world—the justice system—where we seek to determine what actually happened in all criminal matters, large and small. Officer Byrne was one of the many people whose victimhood cried out for vindication. As a prosecutor in New York City, I came to know this story and thousands of others throughout my career.

My professional life was devoted to establishing truth in this admittedly flawed and imperfect system of justice. To paraphrase Winston Churchill’s famous line about democracy, the system of judge and jury is the worst form of justice there is, except for all the others that have been tried.

Why am I bringing up a murder that took place decades ago? What possible relevance could such a crime hold in the present day? Who now recalls the name Edward Byrne?

I remember. A lot of other people remember too. When Edward Byrne was assassinated in cold blood, I was serving in the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor in New York City. The city was in a terrible state back then, plagued by chaos on the streets, and ordinary citizens lived in fear.

I spent almost twenty-five years as a prosecutor in New York City, and I learned all about crime, violence, drug abuse, the criminal justice system, and the people who break the law. I faced off with some of the worst examples of humankind. At the same time, I was working with the best and most dedicated prosecutors and law enforcement officers in the country, tasked with the job of ensuring public safety.

For seven years, I held the position of the New York City Special Narcotics Prosecutor, heading up the only office in the nation solely dedicated to investigating and prosecuting felony drug cases. Prior to that role, I had worked for seven years as the Chief Assistant in Special Narcotics, and before that, I spent a decade as an Assistant District Attorney with the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, the country’s premier prosecutor’s office.

But before all that, I came from rather humble beginnings.

CHAPTER 2

MY HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Both sets of my grandparents came to the United States with the hope of escaping poverty and the pogroms they faced as Jews in Russia. My paternal grandparents and their three-month-old son, Morris, my father, left Russia in 1907 and somehow got to Southampton, England, where they boarded the HMS Saxonia and headed to Boston. Eventually, they made their way to the Lower East Side of Manhattan before finally settling in Brooklyn. My mother’s family came from a town in Russia known as Kalmica, or Kalmykia. It was a small town straight out of Fiddler on the Roof. Most of my mother’s family left for the United States around 1912 when she was an infant. My grandmother was one of eight siblings who had made it to America. According to my relatives, four of my grandmother’s siblings died in early childhood due to the poor medical care in Russia. My mother’s family and some of her aunts and uncles settled in the Bronx. The rest of her family settled in Brooklyn. All my great-uncles worked hard while the mothers took care of the children.

My father was a classic underachiever. Although very bright, he was not very ambitious. He never learned to drive and never made much money in his work as a supervisor for the Miller-Wohl company, which sold women’s dresses. After they married, my parents moved in with my grandparents in the Bronx in a three-bedroom apartment on Rochambeau Avenue. My older brother Steven and I shared a bedroom. It was not a good situation because my father never got along with my mother’s parents. They resented the fact that my father never tried to move up but settled for a fairly low-paying job.

Aside from my grandparents, everyone liked my dad. He had a good sense of humor, was always polite, and he rarely cursed. He read the newspapers every day and was well versed in politics and current events. He was also a very honest man and would get upset when he read about politicians being convicted of taking bribes or committing other dishonest acts. He always said that most politicians were “crooks.” I think it was his dislike of dishonest politicians and other lawbreakers that got me interested in criminal law and prosecuting the bad guys.

My father was the oldest of his four siblings. After finishing high school, he went to work to help support the family and allow his younger siblings to continue their education. One of his brothers, Sam, died in an accident as a teenager when he was riding his bicycle in the street and got hit by a truck. Another brother, Irving, worked for U.S. Customs. My father’s sister, Ray, the youngest of the siblings, went to college and got a degree from Brooklyn College. It was unusual for a woman in the 1940s to attend college. She lived a long and happy life and passed away in March 2023, a few weeks shy of her 104th birthday.

My mother, Tessie, was a housewife. She always had a lot of energy, and she needed it to deal with my grandmother, who had no education, spoke barely any English, and loved to get into arguments with people. Tessie was very creative. When she was in her seventies, she started writing poetry about people and places. She composed witty poems about me, my brother, and my kids. She actually submitted a poem to Reader’s Digest and won a prize for it. She loved being around people and family.

My mother had a sister, Ann, who lived in our apartment house, and a brother, Daniel, who lived in Manhattan. Daniel was a doctor, and was regarded as the prince of the family, mainly because he treated all my relatives for free.

I was born Robert Howard Silbering in the Bronx on June 6, 1947. I have only one sibling, my brother Steven, who is seven years older than me. Steven and I are quite different. My brother was a brilliant student. He graduated from City College and went on to achieve a master’s and PhD degree in organic chemistry from Rensselaer Polytech University in upstate New York. He furthered his education at the University of Minnesota with a post-doctoral degree in pharmacology, then went on to a successful career working for a number of pharmaceutical companies. Unlike me, he did not have an outgoing personality or a big interest in sports. We were members of the same family, but we had very little in common. My mother always raved about how smart my brother was and that he was an excellent student. She continually asked me why I couldn’t be more like him and study and get good grades. She was thrilled when he got his PhD and proudly referred to him as “ My son, the doctor.”

We never did very much as a family. We never went out to eat, and we didn’t own a car. The only vacations we ever took were to the Catskill Mountains for a week where we stayed at a small hotel called the Youngsville Inn. I was the poorest kid of all my friends. While they went to summer camp, I had to make do with hanging around the schoolyard. Their parents all had cars, and they took trips and ate out. I had to work for everything I had. I worked to pay for college and law school, as well as my first new car, a 1970 Plymouth Barracuda. I was never afraid of hard work.

I never felt disadvantaged. I was a happy kid with lots of friends. I felt lucky to be surrounded by loving parents, lots of friends and relatives, and a neighborhood where I felt like I knew everyone who lived in the apartments and worked in the stores that lined the streets. It was a very comforting feeling.

I was blessed to have a reasonable amount of smarts, a good sense of humor, an excellent memory, and the two most important traits to succeed in life and work: good judgment and common sense. I also had an approachable, down-to-earth personality and got along with everyone. I couldn’t afford to be arrogant, and in truth, I had no reason to be arrogant about anything. I had a self-deprecating sense of humor and made people laugh when I made jokes about myself. I never had a big ego and didn’t get embarrassed easily. I was not sensitive to criticism and could handle the unkind remarks of others.

School became a home away from home for me, not because of anything that happened in the classroom, but due to the goings-on in the schoolyard. I attended Public School 80 for both elementary and junior high, with a student body that was over fifty percent Jewish. A Public Works Administration building created in the 1930s, the school remains a touchstone of my youth, but not for the classes I took there.

I was attracted to the sports fields in the schoolyard like a magnet. I would hurry out the door of our apartment building, turn right, and after a short walk along Rochambeau Avenue, I was there. Pick-up softball, basketball, and touch football games were always being played. At home, I would watch a lot of sports on TV, and because I lived in the Bronx, the kids I knew were all big Yankee fans.

That was the golden era for the Yankees, with Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, Whitey Ford, and Yogi Berra, so it was a great time to be a fan of the Bronx Bombers. I had pictures of the players up on the wall in my bedroom. When I went to Yankee Stadium with friends, we usually sat on the top deck behind home plate, paying $1.30 for a grandstand ticket. I spent a lot of time in the House that Ruth Built.

I took the subway everywhere, including Yankee Stadium and Madison Square Garden. When I was a teenager, my friends and I rode the subway all over the place and never really thought about crime or danger.

In my early days, I wasn’t much interested in school. I never had an interest in reading books. Academics didn’t mean anything to me. Even when I graduated junior high and went on to nearby DeWitt Clinton High School, I was only excited because Clinton had a history of excellent athletic teams.

DeWitt Clinton was an all-boys high school that was located a short distance from Mosholu Parkway and P.S. 80. Burt Lancaster had gone there, as well as the Get Smart actor Don Adams. A guy named Ralph Lifshitz attended Clinton a few years before me, who later changed his name to Ralph Lauren. Many other actors and politicians have gone to Clinton as well.

P.S. 80 might have been majority Jewish, but Clinton in my day was pretty diverse, with many Puerto Rican and African American students making up the seven-thousand student body. I might be looking at the past through rose-colored glasses, but I remember us all getting along pretty well.

Whatever subjects I didn’t like, I avoided. I cut geometry all the time because there was nothing I hated more in life than geometry. My truancy got my mother summoned to Clinton to meet with the dean.

“Your son is cutting classes,” he informed her. “He’s a smart kid, but he’s not applying himself.”

She was called to these kinds of meetings so often that she became disgusted. “I think I’m in school more than you are!” she shouted at me one day. Back then, I had a baseball card collection that probably would have been worth real money today. She took all my cards and threw them out.

When I graduated from Clinton in 1965, I did not know what career I wanted to pursue. Well, actually I didknow what I wanted to be in junior high: I wanted to play second base for the Yankees. I gradually came to realize I wasn’t in the same league as Mantle, Maris, and the others. It was a hard day when I faced the sobering reality that I just wasn’t going to be good enough.

My next passion was to be a sportscaster. From watching Yankee games, I knew the language of sports, the play-calling, the patter, and the routines. I knew how the game was supposed to be played and who all the characters were. Mel Allen, the great Yankees announcer, was who I aspired to be, and I could imitate his style with uncanny accuracy.

But a career in sports broadcasting wasn’t in the cards either. My grades were not stellar; they were okay, but not great. I went to the required senior-class interview with the school guidance counselor.

“I can suggest the colleges you should apply to,” he said. “Since you don’t have the best grades, you’re not going to get into City College, and you’re probably not going to get into Lehman or Baruch. What about a solid SUNY school like New Paltz? Or maybe you should consider private schools.”

In the end, I chose Fairleigh Dickinson University, across the Hudson River from the Bronx in Teaneck, New Jersey. It seemed to me I was simply settling for the best school that would have me, but the school turned out to be a lot more than that.

I came to the realization that I had to take school seriously and not goof off anymore. Fairleigh Dickinson University—affectionately referred to as “Harvard on the Hackensack”—lit a fire under me. I had more or less wandered through high school, but as I started college in 1965, I felt myself emerge from intellectual limbo. I began to get interested in the material I was learning. I managed to finish my freshman year as an A student, a status that I had never achieved in my life. My curiosity about the world woke up. Maybe I had just matured a bit. Everything about studying and learning just seemed to click. It was during my freshman year, after taking a Constitutional Law class, that I started to think about a career in law.

While I was in college, I had virtually no spending money, and my parents certainly had none to give me. A boy with empty pockets needs to work. Thankfully, my uncle Daniel, the doctor, helped me out in that respect. He had a second home in Bridgeville, a small town in the Catskill Mountains near Monticello, New York. During his time in the area, my uncle had met the owner of the Salhara Hotel in nearby Woodbourne. He was able to land me a summer job.

This was the mid-1960s, marking the tail end of the golden age of the Catskill resort culture. The entire region was already dwindling from its peak in the 1950s, when over five hundred hotels, bungalow colonies, and summer camps dotted the landscape of upstate New York. “The Jewish Alps,” we called it, and the clientele was, in fact, overwhelmingly made up of Jews from New York City and the larger metropolitan area. Businessmen sent their families to the Catskills to beat the summer heat and would join them for the weekends.

If you’ve ever seen Dirty Dancing, read the Herman Wouk novel Marjorie Morningstar, or watched the TV series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, you might have a good sense of what the scene was like. But the real phenomena was ten times as intense as any writer could portray. It was a different era, the heyday of the Borscht Belt, with nightly entertainment from comics, singers, and dance bands.

In the summer of 1966, at the age of eighteen, I started out as a bellhop, schlepping luggage and on occasion helping out as a busboy in the dining room. The next two years I moved up to be a busboy and a waiter. It was a long workday. I got up at seven in the morning, had a quick breakfast, then helped prepare breakfast for the guests. By the time breakfast finished, it was ten-thirty and time to clean up and set the tables for lunch, which started at one. After a short break in the afternoon, the dinner rush was on at seven o’clock.

I loved the job. I had a great time schmoozing with guests and making good tips. Almost every night after work, the waiters, bellhops, and other staffers went out together. I was in college boy heaven.

After that first summer, the Salhara went out of business—a harbinger of the decline of the Catskill scene. But I was hired at a place called Green Acres the next summer. A year later, in 1968, I was hired as a waiter at Esther Manor hotel.

In 1968 it was the Summer of Love, when the flower child craze was in full bloom, but I was pretty much oblivious. The revolution would have to happen without me. The owner’s daughter at Esther Manor was married to the singer Neil Sedaka. That’s about as close as I ever got to rock and roll.

That year I was a waiter, and because I had such a good memory, I didn’t have to write anything down. I did well in that role. I was able to remember all twenty-four separate orders for three tables of eight. That meant I could be the first waiter in the kitchen and was able to get everything taken care of early on.

The mountain air of the Catskills encouraged relaxed attitudes, the loosening of belts, and the corny comic routines of kosher comedians (“My doctor said I was in terrible shape. I told him, ‘I want a second opinion.’ He said, ‘All right, you’re ugly too!’”). Everyone, staffers and guests alike, seemed to be some sort of character.

I had a customer who I always addressed formally as “Mr. Fox.” Every day after dinner, he would take me aside.

“Bobby,” he said, “firstly, if I can put my finger in this coffee, it’s not hot enough. And secondly, do you have an extra steak or lamb chop you can give me to take back to the room for my dog, Tiny?”

He was at the resort for a week, and every evening it was the same routine: hotter coffee and a chop for his pet. When the weekend rolled around, I ran into Mr. Fox for the last time while he was packing up his car and leaving with his wife.

“Hi, Mr. Fox,” I said. “Wait. Where’s your little dog?”

He grabbed his bulging belly with his hands. “You wanna see Tiny? I’ll show you Tiny!” His wife cackled like a banshee and they drove away.

I worked in the Catskills for three years, during summer breaks. I consider it a great, entertaining time of my life, a period that also taught me to be independent. Those summers represented the first time I was really ever away from my family. I also made a few bucks, which helped pay for my education.

In my senior year at Fairleigh Dickinson, I was doing so well that the school granted me a partial scholarship. Majoring in American history and government, I took my degree and graduated with honors.

After I graduated from Fairleigh Dickinson, my first thought was to continue my education and go to law school. But the Vietnam War was raging, and law school offered no protection from being drafted into the military. I was no peacenik, but I didn’t want to be used as cannon fodder either.

Luckily, Jeff Cohen, a college classmate I am still close with today, pointed me in the right direction. He told me that educators who taught in underserved neighborhoods could get an exemption from the Selective Service. Following Jeff’s lead, I landed a job teaching sixth graders in Paterson, New Jersey, even though I had never taken a single education course in college.

While teaching in Paterson, I got my first taste of violent, impulsive tendencies in juveniles. This would become all too familiar to me later when I was working in Family Court. Paterson was a decaying mill town, rough around the edges and rough in the middle too. The students were a mix of white, Hispanic, and Black. The one thing they had in common was that they all came from poverty-stricken backgrounds.

Most of the teachers in Paterson Public School 8 had basically resigned themselves to the idea that this was just a job and these kids were not going to be educated. The administration occasionally brought in substitute teachers who wouldn’t last a day in the tumultuous school environment. One time, I left my classroom for all of two minutes and returned to find one of the students had been knocked out cold.

I have to say I surprised myself. I enjoyed the experience. I met a lot of memorable characters. The principal was definitely not the right guy for a place with an atmosphere like P.S. 8. One day, I heard a squawk from the intercom in my classroom, and it was the principal.

“I have just apprehended one of your students,” his disembodied voice informed me. “I found him tap dancing and doing other un-American activities on the stage in the auditorium. I’m giving him twenty lashes with a wet noodle and sending him back to your classroom.”

Discipline was hit and miss. In a nod to their deprived home environments, the students all received a daily ration of milk. A kid named Fernando used to come to class with snacks his first-generation immigrant mother baked. Fernando called one snack “squirrel nut cookies,” while another was a smelly kind of onion cookie. He’d eat the onion-flavored one and then run around the classroom breathing into the faces of his classmates, grossing them out.

“Fernando, you can’t do that,” I told him.

“You’re not my mother,” he sassed back. “You don’t get to tell me what to do.”

He wouldn’t quit. Day after day at milk time, it was the same routine. Finally one day, as he dashed around breathing onion fire, I had had enough.

“That’s it, my friend,” I announced. “You’re going to the principal’s office.”

I opened the door to usher him out of class. He leaped up from his seat, ran to the back of the room, opened the window, and jumped out. It was a ten-foot drop to the ground. The whole class, me included, rushed to the window and watched the little kid scurrying away into the distance.

That was it for Fernando. P.S. 8 never saw him again.

Around that time, and without really realizing it, I began another phase of my education, just as vital as anything I ever learned in class. I met my future wife, Shelley, on August 15, 1970.