Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

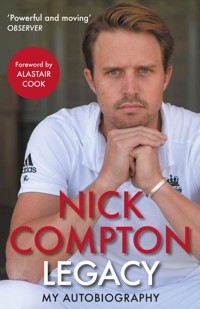

*SHORTLISTED for Cricket Book of the Year at The British Sports Book Awards 2024* FOREWORD BY ALASTAIR COOK Who ever hoped like a cricketer? Nick Compton has an incredible sporting ancestry. A literal golden boy, his grandfather Denis Compton played cricket for England and football for Arsenal. Honed at an elite English boarding school, with a telegenic profile perfectly suited to the modern media environment, Nick appeared to be blessed with that rare ability to be able to stride out and face down the world's quickest bowlers, to survive and thrive in the danger zone of the hurtling new ball. However, greatness in any field comes at a price and this gripping memoir explores the almost 'Faustian pact' he made in order to secure that time in the sun as a key member of an England team alongside such greats as Alastair Cook, Kevin Pietersen and Ben Stokes. It will show what 'Mistress Cricket' demanded from Nick as his side of that bargain. The family he left behind, the failed relationships both personal and professional and the utter physical and mental exhaustion which resulted from his drive to stay at the top.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Legacy

Nick Compton is a South African-born English former Test and first-class cricketer who most recently played for Middlesex County Cricket Club. The grandson of Denis Compton, he represented England in 16 Test matches, scoring two centuries. A right-handed top order batsman and occasional right-arm off spin bowler, Compton established himself as a consistent scorer in county cricket for Middlesex and Somerset, and following a prolific domestic season he made his England Test debut against India in November 2012.

In April 2013, the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack named Compton as one of their five Wisden Cricketers of the Year.

Compton retired in 2018 and is now a professional photographer and broadcaster.

Legacy

Nick Compton

with Robert Wainwright

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2024 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Nick Compton, 2023

The moral right of Nick Compton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Plate section photography credits: Page 2 – top photograph by Clive Rose/Getty Images, middle photograph by Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, bottom photograph by Philip Brown; Page 3 – top photograph by Jan Kruger/Getty Images, middle photograph by Harry Engels/Getty Images, bottom photograph by Philip Brown; Page 6 – top photograph by Mitchell Gunn/Getty Images, middle photograph by Sarah Ansell, Getty Images; Page 7 – bottom right photograph by Philip Brown; all other featured images courtesy of the author

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 827 5

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 826 8

Printed in Great Britain

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my parents, Richard and Glynis.

Contents

Foreword

Prologue

1: Old and new

2: Grandad

3: The obsession

4: To Harrow and beyond

5: The impatience of youth

6: ‘You’ve done nothing, mate’

7: A breakthrough

8: A new beginning

9: ‘Just don’t ever get out’

10: The Compton Cricket Club

11: A dream realised

12: This isn’t going to be easy

13: A series win and niggling doubts

14: Proving my worth

15: A sense of injustice

16: ‘They simply don’t like Nick Compton’

17: A Middlesex recall

18: A clean slate

19: So near and yet so far

20: Walking the Lord’s plank

21: An inevitable conclusion

22: A lens on life

23: The graft behind the craft

24: A sum of its parts

25: A legacy of my own

Acknowledgements

Foreword

by Alastair Cook

There is much to admire about a player like Nick Compton and much to learn from his story about the challenges to reach the top in elite sport.

When he and I walked out to open the batting for England it was comforting to know that the man beside me had left no stone unturned in his quest to do the best for himself and the team, and that this guy was going to sweat blood for the team whether he scored 0 or 100. To be part of a history-making team in India in 2012 is very special and he should be very proud of his achievements in the England shirt.

In the book Nick writes so honestly and openly about the challenges he faced. In professional sport, fans and supporters only ever see the external result and the public image. The internal turmoil that no one sees is often the challenge that is hardest to overcome. Nick speaks about his personal struggles throughout the book and if this helps up and coming sportsmen and women, his legacy off the field will be as important as his career on the field.

My favourite times as England captain was always selecting and telling people they are going to make their debut. Making people’s dreams a reality was a very special moment and an honour that I found a massive privilege. Then watching those players perform and make a difference for the team was equally special. I was watching from the stands when Nick made his first hundred at Dunedin and I’ll never forget his release of pure emotion as he ran down the pitch for the single that took him to his hundred. It was spine-tingling to watch because you knew how much he had gone through to be the best batting version of himself.

In elite sport you tend to concentrate on your own challenges and sometimes forget the struggles of those around you. Perhaps as captain I didn’t appreciate enough the battles other players around me had had to overcome to get to the same place. It’s a great lesson and a reason why a book like this is important. It is very brave for Nick to be able to talk publicly about issues such as mental health.

The other reason I admire Compo is that he had the fortitude to accept his disappointment at missing out on the 2013 Ashes series and the resilience and strength to bounce back and regain his place in the team. It is one of the truly great challenges of sport for a player to overcome rejection, and he should be proud of what he achieved. I wish him well in the second half of his life.

Prologue

Who ever hoped like a cricketer?

It was one of those days. The sun was shining down on Lord’s on the first morning of the third Test against Sri Lanka in June 2016, the packed house lathered in sunscreen under cloudless, bright blue skies. Commentators shared buttered crumpets as they watched the teams warm up on the cross-hatched emerald green outfield while Alastair Cook was presented with a commemorative silver bat for passing 10,000 Test runs.

It was, as the Scottish cricketer and writer R. C. Robertson-Glasgow observed above, a day full of promise and hope.

The match itself was a dead rubber. England had already bullied a 2-0 lead and the home crowd wanted more of the same. The other interest was in me – ‘Nick Compton, a man with plenty on his shoulders’, as one media story observed because this was my last chance to remain an English Test cricketer, and everybody around the ground knew it.

It should have been perfect. This was the ground where my grandfather, Denis, had become a legend of the game and who once wrote about Lord’s: ‘When you are there you feel yourself at the very heart and centre of cricket and immersed in its essential moods.’

But it wasn’t.

Alastair won the toss and batted. I was due in at number three, but instead of itching to get out there and into battle, I sat watching with increasing dread as he and Alex Hales put on a half-century stand until Alex tried to knock left-arm spinner Rangana Herath out of the park and was caught behind.

This was it then. I tried to gee myself up. I had faced moments like this before and triumphed, like against New Zealand in 2013 when I scored my maiden century to silence those who believed I was not up to the task. But the sense of dread remained as I walked past the line of assembled MCC members, through the famous Long Room and descended the steps from the pavilion and into the sunshine.

I walked through the picket gate and looked up and out, trying to drink in the wonderful atmosphere to settle my nerves. Should I look at the Denis Compton grandstand? I wondered. No, I decided. Grandad’s feats suddenly hung like a shadow rather than a source of inspiration, the hammer in my chest the expectation of failure rather than Robertson-Glasgow’s hope of a big score. At that moment, on a stage built for the name Compton to shine, something had changed inside me.

I blocked the last two deliveries of Herath’s over and then watched Alastair play out a maiden over from Suranga Lakmal. As I waited for Herath again, a thought flashed through my mind:

I can’t do this any more.

Patience and resilience, the ingredients of my success, were suddenly monotonous. I didn’t want to go through the routine of an hour of pain to reap the rewards of later, patient runs. The thought shocked me. My brain had gone and I wanted to walk off the ground. I was shot. Useless. My body was screaming at my brain, ‘What’s going on? I felt like a marathon runner exhausted at the start line thinking about the 26 miles ahead of him. But my brain wouldn’t listen. It was heartbreaking, battling with myself in the middle of Lord’s, in front of thousands of people including my father, Richard. It was as if the 25,000 spectators could all see what had just gone on inside my head.

I had never felt this way before. Normally when I was at the crease I was steely and resolved, but the fight had gone. Somehow I pulled myself together and managed to get off the mark with a single to mid-off, but the dismay had set in as I defended without conviction, almost hoping that a delivery would get past me and end the misery.

I got my wish two overs later when Lakmal pitched one up and the ball moved ever so slightly away down the Lord’s slope. I wasn’t far enough forward and reached away from my body, getting a faint edge and was caught behind. I felt the sorry silence as I walked off the ground.

The runaway train had finally come off the tracks.

Chapter 1

Old and new

I am an unfinished person.

When I first thought about writing a book, the term autobiography didn’t sound quite right. I had retired as a professional athlete but it seemed far too early in my life to review its ups and downs. More to the point, I questioned whether I had achieved enough to warrant a book. Sure, I played Test cricket for England – only 653 people had achieved that honour when I was capped in 2012 – but I had fallen short of my potential and expectations, so I had to ask if my story would make a meaningful contribution to the game I love.

But on reflection I believe that these flaws are actually the strengths of my story; a life in motion, both successful and imperfect, conflicted by battles with mental illness and now in the midst of change, not just in circumstances but in a sense of the person I am, and whom I want to become, all against the backdrop of my family’s cricketing legacy as the grandson of English cricket icon, Denis Compton CBE.

At the time of writing, I have just turned thirty-nine years old. I played sixteen Test matches for England between 2012 and 2016, during which time I was part of teams that won a Test series in India for the first time in almost thirty years and also defeated South Africa on their home turf. I hit more than 12,000 runs in first-class cricket for Middlesex and Somerset, including twenty-seven centuries, and finished with a decent average of 40.42.

But that career is over, and my challenge now is to find the new Nick for my new life. After all, given reasonable health I am not even halfway through my existence. But to do that I have to re-examine and learn from the old Nick, and that is what this book is all about; reliving what has happened to this point in my life and reflecting on my decisions, good and bad, so I might learn about myself and can get on with the next stage of life and, in doing so, hopefully help others who are struggling with similar problems. Being grateful and giving back.

The old Nick. It seems a strange description, given that it is about my younger self. Perhaps former is more accurate, although that implies a desire to shed a skin and rid myself of that character, and that would be just as bad as not changing. I want to evolve; to keep the best bits of young Nick and add life skills and technique to get better, just as the thousands of hours of practice I sweated in the nets over the years made me a better batsman.

The old Nick had the focus and desire to get to the top of his chosen profession; to become an elite cricketer who played for England, scored two Test centuries and helped his team win four of the five series in which he played.

And yet I continue to live with regret – some of my own making and some the creation of others – and struggle to regard what I achieved as success. To me, it reeked of failure because of what I didn’t do. Some would agree with that sentiment but there are others around me – people I trust – who tell me that my greatest personal challenge is to accept what I achieved and move on. That I need to be comfortable with myself. Sure, I should continue to strive to be the best I can at what I do, but not to place success, as I see it, at the centre of my world.

This is not easy. Not with my complex personality. I am, I admit, a flawed man who has had to contend with mental illness throughout my life. I know this and I rail against it every single day. I have always struggled against insecurities, real and imagined, and to feel as if I belong. I’ve batted away suicidal thoughts on occasions, and even wondered about how to end my life. I’ve drawn the curtains and hidden, distraught in my hotel room away from my teammates during a Test match tour and cried uncontrollably driving home from a county match, simply because I’d got out due to a stupid loss of concentration.

These feelings are raw; they hurt although the anxieties and crippling vacillation remain mostly hidden. Most people only see a six-foot-two, blond and blue-eyed athlete who seems slightly arrogant and speaks his mind, at times with little or no filter. I have been misunderstood and, at times, dealt with unfairly as an outsider; somebody with talent – natural and practised – but frequently too difficult to deal with, too opinionated and emotional.

Rather than acknowledge and reassure me about my best attributes and help me cope with my worst frailties, it was easier to set me aside and try someone more stable. With better management, I could have been a longer-term part of English cricket that for eight years after my last Test for England could not find a successful opening partnership.

This failure was, of course, partly due to me, my performances and my personality, but it was also partly to do with a creaky, old boys system that still struggles to recognise outsiders or those who don’t quite fit the English mould. Someone like me.

This book, then, is a story rather than a record of triumph. It is a memoir but it is also a book from which I can create a new, more resilient and more resourceful me, and give some guidance to future players about what it takes, not only to get to the top in terms of work ethic and determination, but also the importance of taking the rough with the smooth; to back yourself but be comfortable with your mistakes as much as the successes.

Elite sport is not only about physical skill and dedication but also about being a complete person. Those who succeed at the highest level for the longest time generally manage to balance those aspects of their character.

I am not alone with many of these challenges, but my story is unique because I made a pact with a legacy that with hindsight I had almost no chance of satisfying. Now it’s my turn. But what legacy can I leave?

Chapter 2

Grandad

My grandfather was not only regarded as one of the best batsmen of his generation, but among the greatest cricketers ever to play the game. Denis Charles Scott Compton, youngest son of a painter and decorator from North London, was an entertainer, wielding a rapier made of willow who made England cheer again in the dark post-war days of austerity. He brought instinct, flair and vibrancy to the game, standing up to the ‘Invincibles’ Australian side led by Don Bradman in 1948 and hitting the winning runs when England finally reclaimed the Ashes in 1953 in front of a baying crowd at The Oval.

His iconic stature was probably best captured by the great writer Neville Cardus who wrote of his phenomenal performances in the summer of 1947 when he scored 3,816 runs at an average of 90, including 18 centuries:

‘Never have I been so deeply touched on a cricket ground as in this heavenly summer, when I went to Lord’s to see a pale-faced crowd, existing on rations, the rocket-bomb still in the ears of most, and see the strain of anxiety and affliction passed from all hearts and shoulders at the sight of Compton in full sail, sending the ball here, there and everywhere, each stroke a flick of delight, a propulsion of happy, sane, healthy life. There were no rations in an innings by Compton.’

But to a young boy growing up five decades later in faraway South Africa, he was just Grandad who once played Test cricket for England and football for England and Arsenal (with whom he won the League Cup and the FA Cup) and advertised a mysterious hair gel called Brylcreem. I was proud, obviously, and had posters and photographs of him on my bedroom walls, caressing the cricket ball through square leg or dressed like James Bond in black tie while signing autographs for wide-eyed girls.

But I was too young at that stage to really understand what he had achieved. On the few occasions that I was in his company it would not have occurred to me to ask him what it was like facing Ray Lindwall or Keith Miller, the Australian quick bowlers of his day. I was more interested in my own, present-day heroes; I wanted to be one of the South African stars, Jacques Kallis or Jonty Rhodes or Andrew Hudson.

I didn’t see much of Grandad when I was a kid, other than a handful of trips he made to South Africa or the few occasions that we came to London. He was an unseen presence in our lives, the reason that people in the street and the sporting clubs of Durban knew our names, although not one to mention in front of his ex-wife, my late, rather regal grandmother, Valerie.

The first visit I recall was when I was about eight years old and a tearaway striker for the local football club. It was the first sport in which I had showed real promise, selected in underage Natal teams. I was quick and incredibly competitive, even at that age, and out to impress my famous relative. If I close my eyes and concentrate, I can still smell the orange wedges the coach was handing out at half-time that day in a small suburban park while Grandad sat watching from a rickety grandstand by the side of the pitch.

I scored a hat-trick and one goal, in particular, was spectacular. I was playing on the left-hand side of the pitch where I got the ball and dribbled down the touchline before switching inside, around an opponent to the edge of the box and hitting it into the top right-hand corner of the net, just like he used to do when he played for Arsenal. My father remembers Grandad leaping in the air despite his gammy knees and yelling ‘That’s my boy’ as I scored.

Grandad came back to Durban a couple of years later and visited my prep school. It was at this moment that I had an inkling of just how famous he was when the headmaster and teachers rolled out the red carpet for him. Everyone was in awe of Denis Compton, and I could now picture what it was like to be a champion.

I was twelve years old when he first saw me play cricket, not in Durban but in England. I had come on a school tour, accompanied by Dad, and stayed with him at his home in Burnham Beeches, in Buckinghamshire. He came to watch me in a match played at the nearby Caldicott School where I think I got 45 out of the team’s total of 120.

Dad told me that Grandad had turned to him and said something like: ‘You know, he’s got some fight in him, this kid.’ Those sorts of comments really meant something to an impressionable child, not just in the moment but as my career went through its ups and downs. Whatever anyone else observed of me out there in the middle, fight was the word that came to define my own view of myself.

Dad and I stayed on with Grandad for a week after that tour, during which time there was another significant moment for me. I was in his back garden one day, practising diligently as Dad patiently threw balls. Grandad was watching, sitting at a table on the veranda sipping brandy, as was his wont. I was trying to show him how straight my bat was, blocking the ball carefully back to Dad, but after watching for a while, Grandad blurted out: ‘Oh, for heaven’s sake, just hit the bloody thing.’

I never forgot that, not just because of the way he shouted it in frustration but because, like the word ‘fight’, it became very pertinent to my career. In my worst times, when my confidence was low, I had a tendency to overthink things and become too technical. There were times when I got stuck like that out in the middle and I’d just remember his words and think, Oh for fuck’s sake, stand still and just hit the damn thing. It made the game simple.

As much as we were compared during my playing career, the truth was that Grandad and I were cut from very different cricketing cloth. I mean, I was into fitness and health drinks and he had the fortitude of an ox, getting to the ground after a night partying and then going out with a bat borrowed from a tail-ender and scoring a century. That was the mythology at least.

He had real charisma on and off the field, a man of the people long after he finished playing who, when not at Lord’s, could usually be found at a private members’ club, The Cricketers, off Baker Street where he was president and used to go for long lunches most afternoons, holding court with his lunch companions and other admirers in the restaurant who would gather to hear him tell stories. He had this manner where he would lower his voice, almost to a whisper, to ensure that people would crowd forward to hear what he had to say before launching into a rakish story about his friendship and adventures with his great mate, the Australian all-rounder Keith Miller with whom he had battled for the treasured Ashes.

The Brylcreem (an emulsion of water and mineral oil stabilised with beeswax) that defined his image as a player was long gone and his jet-black hair was now a lush silver, but he cut a broadening but well-dressed figure who could speak with a clipped accent despite his working-class background.

He was also Middlesex president at the time and took me around Lord’s one day, past the stand that bears his name. Here I was, a twelve-year-old with eyes as big as dinner plates, walking around the palace of cricketing dreams. It cemented my desire to play there, particularly when he arranged for me to pad up and face Mark Ramprakash and Gus Fraser in the nets. I couldn’t have guessed then that Gus would be my captain five years later when I made my debut for Middlesex. It’s unfortunate that Grandad wasn’t around to see it. He died the year after that memorable underage tour, aged seventy-eight.

Was Grandad an influence on my life as a cricketer? Of course he was. Was he the reason that I wanted to play cricket? No, I had a bat in my hand from the age of three, although his achievements were certainly a driving force for me to succeed at the highest level. His legacy did not ensure my selection to play Test cricket but it cleared away some of the branches hanging across the pathway towards the top, especially in the early days when the name Compton meant something in a place like Natal.

But there was a flip side to this legacy. The shadow of expectation and comparison was constantly on my shoulder. I did not feel it so much as a youngster, but the higher I climbed in the game the more it bore down on me. For the most part I didn’t feel the pressure, especially when I was playing well, but I could sense in others the rush to compare, particularly in the media which either delighted in slicking back my hair with Brylcreem for photo shoots or, when I was down and struggling, drawing unflattering comparisons between my slow, methodical batting and his cavalier scoring. But I don’t remember ever thinking I’m not as good as Grandad. I just wanted to be the best player that Nick Compton could be.

Some of this analysis was, of course, valid. After all, cricket is a game of statistics, and I am the first to acknowledge that performance is everything in terms of team selection. But statistics can also be misleading – between matches and seasons, let alone generations – so they should always be made carefully with context.

Our challenges were different. It was much less about brawn and power back when he played. The bats were thinner and lighter and the pitches weren’t as good, so the sweep and the late cut were examples of the touch and the ability to manoeuvre the ball rather than just hit through the line. Batting techniques were more individual.

I was brought up on coaching manuals and bowling machines, heavier bats, true pitches and raw, fast bowlers. My visual cues came through hours of television and video analysis, watching the best players and copying techniques. It was one of the many differences that makes a direct comparison between Denis Compton and his grandson Nick across sixty years neither flattering nor fair.

*

Grandad had another significant influence on my life which had nothing to do with cricket.

As much as I don’t like to say it, I don’t believe he was a terrific father. He was a man of the people but that devotion came at a cost to his own family. My grandmother Valerie Platt was his second wife, an heiress to a sugar plantation whom he married in 1951. There is a short video of the wedding on YouTube which showed the media excitement of the event and the vast seafront plantation her family, the Platts, owned at Isipingo on the outskirts of Durban.

Grandad was filmed lighting his fiancée’s cigarette, arm in arm as they walked down the path to the Old Fort Chapel in the centre of the capital, surrounded by cameramen, although she seems to be leading him. In contrast to his easy smile, hers is tight although it was probably nerves. He was forty-three years old, his cricket career coming to an end, and she was just twenty-four. The marriage ended, effectively at least, nine years later when she took the youngest of their two sons – my father Richard who was aged five – and returned from London to Durban to raise him on her own.

It was said later that Valerie was homesick, hated the dank English weather and wanted her sons to grow up with sunshine on their backs, but it only partly rings true. It wasn’t that easy to get divorced in those days so a deal was reached in which Patrick would stay with Denis and Dad would go to South Africa with his mum who then packed him off to boarding school at the age of seven. Patrick was also dispatched to boarding school and hardly ever saw his father, instead fostered out to a family named Wallace during most holidays. Separating the brothers had an effect on both of them.

My uncle eventually returned to South Africa to attend university. He became a leading sports journalist and once considered writing a book about Denis but didn’t go ahead: ‘Who am I to dismantle a legend?’ was his explanation, which gives a hint of the darkness that lay in our family.

I loved Grandad, but it is true that he preferred the company of his mates at the pub and the cricket club rather than the domestic environment of the family home. Amazingly, he married for a third time in his sixties and had two daughters who I hope had better childhood memories than their half-brothers.

The decisions that Grandad made and the life he led had an impact, not just on his children but, I believe, also on the next generation. One incident in particular embodies the attitude Grandad had to being a parent. He had made a rare visit to South Africa one year, long before I was born, and was going to see Dad who was a young boy playing cricket for his school, Michaelhouse. The famous cricketer arrived at the school to much fanfare but was promptly whisked away by a few of his friends who hauled him off to the local pub, missing the game and leaving Dad embarrassed and deflated.

I have fond memories of being around Grandad – as few as those were – and, on reflection, I think his presence also brought my dad alive a bit as well, perhaps filling the deep need that he must still have felt growing up without a father figure. We’ve never spoken about it. Maybe we should.

Most memorable was the night we all attended the filming of the TV programme This is Your Life. I was almost four years old and Alex was just six weeks old. We had flown over from South Africa to stand behind the curtain in the television studio with other members of his family and friends from around the world, while Grandad was led on to the stage on the pretence that he was being interviewed. That’s when the curtain opened and Mum remembers his honest response – ‘You’re joking!!’ It was all very exciting, especially when I was allowed to attend the post-event party. I ended up guiding my rather merry father back to the Tube station afterwards.

Chapter 3

The obsession

I have never considered myself to be normal; in fact, I have always railed against the description. What is normal anyway? The more we learn about the human brain, the more we realise that there is no such thing as normal. We are all different. We are all individuals.

The dictionary defines being normal as ‘conforming to expectations’ and there are seventy-odd synonyms in the Thesaurus – words such as ordinary, regular, typical, run-ofthe-mill, habitual etc. – so you see where I’m going with this.

To me, being normal meant failure. Even as a kid I wanted to be the best at everything I tried, and growing up in the sunshine of South Africa, that meant sport. Not just cricket but athletics and rugby, hockey, tennis, soccer, swimming. I was good at them all, fortunate to be born with elite sporting genes that were supercharged by my own insane desire to win.

Richard Compton met Glynis Duckering in the newsroom of the Durban paper the Daily News in the early 1980s. He was a sports reporter and she was a general reporter and later a senior layout and design editor, daughter of an artistic family of teachers. They were married in 1983 and I came along later the same year, followed by my sister, Alex, three years later. A boy and a girl – nice and neat – although we were chalk and cheese. While I banged and crashed around the house in my sports gear, demanding attention, she was quiet and loved art, dance and animals.

Dad left the paper around that time and started his own communications company, including creating and presenting nature documentaries which went to air every Sunday night in a programme called 50/50 on the main television channel, TV1. I often turned up to school on a Monday to a chorus of calls that ‘I saw your dad on TV last night’, whether that was stalking a white rhinoceros in South Africa, swimming with whale sharks off Mozambique or tangling with orangutans in Borneo.

His work had a huge influence on me and my love of nature, ultimately leading to a passion for photography, but the visual arts was also embedded in my family genes, particularly on my mother’s side. My mum and her three sisters all paint – one professionally – as does my sister. Their father, my maternal grandfather, also painted although his greatest passion was wildlife photography, and he won a number of awards while the family lived in Zimbabwe.

But first and foremost came cricket. My mother has a grainy, slightly blurred photograph of me aged three, leaping and grinning with a plastic cricket bat in my hand. From the age of nine I knew exactly who I was and what I wanted to be: I was Nick, the cricketer who would one day play for England – a single, emphatic ambition. The reason was simple; yes, I was South African, barracked for South Africa, doted on their stars and would have been proud to play for the national team, but as a family we were completely aligned with England because of Grandad’s legacy.

The light-bulb moment about being a cricketer came when I played in a schools match. Until then I had been a medium pacer who batted in the middle order, but on this day I was asked to open the batting. I scored 64 not out and hit something like five sixes. I rushed off the ground to my father who was watching: ‘Dad, Dad, did you see what I just did?’ The expression on his face confirmed to me that he knew I had talent.

It made me feel special to tell people of my plans. I didn’t stop to think how it would sound to them. I wasn’t self-aggrandising after all, suggesting that I could be something unreachable, like an astrophysicist. No, I wanted to be a superhero cricketer, just like my grandfather had been. Why was that surprising?

The problem wasn’t that I had ambition – after all, many of us have such childhood fantasies – but that it became an obsession, an all-consuming desire to succeed, measured in black and white by runs made at the crease. It was as if my happiness was dependent on the numbers scrawled in a scorebook, and if I didn’t score well then I felt empty and useless. Anxious. Instead of a positive direction and goal in life, my ambition became a twisted yardstick of safety and security.

I can’t pinpoint exactly when I began to feel this, but Mum tells the story of when I was aged ten and we went on holiday with family friends into a game reserve in the heart of the northern bushland. I was excited at the prospect of seeing animals in their natural habitat. We arrived and the tents were set up in a circle which I apparently immediately recognised as a natural cricket amphitheatre. Gone was my interest in the wildlife; instead, I organised cricket matches and roped in not only the family but also the rangers. My godfather Tony Bradshaw, an English journalist who had met Mum and Dad when he came to South Africa to work, bore the brunt of my enthusiasm on that trip, and it would not be the last time he stepped in at critical moments in my life.

Dad remembers visits to the beach where, instead of being satisfied with a swim, I wanted to play beach cricket. It was never-ending.

Mine was an obsession that quickly became a lonely place where nothing else could satisfy me. Instead of making neighbourhood and schoolyard friends, I withdrew into a fantasy world where I was that superhero. I found myself daydreaming about Test match heroics at school where I could see the nets from the classroom window. It seemed a much easier place to exist, dependent on no one else and without the commitments of the real world. Of course, I was a child and couldn’t see that my fantasy was actually a torture.

A first I had school friends with whom I played cricket in the street or I would invent games to make the challenge harder, but as my obsession grew, the friends disappeared, frustrated by my intensity and dominance, and I was left with Dad or our gardener (it was normal for middle-class families to have paid domestic help in those days) who would throw balls for me in the backyard; so many that he complained that he couldn’t clean his teeth because his shoulder was so sore.

I remember one night at the age of twelve sitting on the edge of my bed, tearful and worried about the selection of a district cricket side. Mum sat next to me, her arm around my shoulders protectively, as attentive and loving as any mother could be. She was sure that I would be selected but if I wasn’t then there would be other opportunities. It wasn’t the end of the world, she said reassuringly. But I wasn’t convinced. I wanted this more than anything; it seemed life and death to me and yet, of course, it wasn’t. At one point I turned to her and declared tearfully that if I didn’t succeed then I wanted to be put down like a horse.

Did I mean it? Sadly, the answer is yes. Even now I can feel the anxiety of that moment. That desperation. In many respects it set up my life and everything that came afterwards – my successes and my failings. It’s one thing to be driven to succeed and another to be fixated to the point of psychological self-harm.

For many of those around me it was difficult to see the inner turmoil. Outwardly, I appeared confident if not precocious; so opinionated that I was once replaced as captain of my primary school team because I questioned the way we were being coached and insisted on being allowed, as captain, to do things ‘my way’. And yet inside I was often in knots. It’s not something I chose to be and often wished I could simply cut off all emotion. It remains a daily struggle.

*

I have been medicated for depression in one form or another since I was thirteen, diagnosed after collapsing one day at high school, but I have now weaned myself off them because I’d had enough of the way they made me feel. I wanted to know the real Nick Compton.

I have always been difficult. ‘Damn difficult,’ corrects my mother, ‘and obstinate,’ she adds. Mum has borne the brunt of my problems over the years, calming me in my worst moments and being the oil on troubled waters inside the family.

My dad and I have had our ups and downs, like many other father-son relationships no doubt. We are similar in many ways, certainly physically. He’s a big man with a big presence. People notice him when he walks into a room. He’s also a contrarian, so if he sees people walking left then he will deliberately walk to the right. Just like me.

He loves to travel and has a way with people, particularly in the tribal villages of the Zulu where he has always been welcomed. I feel the same connection, particularly since retiring from cricket and travelling with my camera. The image files from places I have visited like India, Nepal and Sri Lanka are full of village people and their daily lives. Despite my personal social difficulties, I feel as if I have evolved as an adult and have the ability to connect with different people from around the world. I find it easy to talk to strangers sitting on a bus or in a restaurant. I like being able to converse with someone who could just as easily have been ignored. It’s these conversations and friendships, some of them out of nowhere, that give me a reason to live and to be proud. I have met some amazing, quirky and unique people, nevermind their status or colour. Africa and my father have given me that sense of touch and compassion.

But yes Dad and I are also very different. Sporting ambition is a glaring example. It must have been much more difficult for him than me, growing up under the shadow of expectation of his father. Dad was a handy cricketer, a fast-medium bowler and middle-order batsman who played first-class for Natal, but he never pursued his sporting career further. Instead, he loved the game, playing for South African Council on Sport teams, the non-racial sports organisation of the 1970s and 1980s that resisted apartheid.

His political stand should be a point of pride for me but it has, in the past, been a point of conflict between us, particularly in my youth. I didn’t understand that desire had different levels, and that not everyone wants to be an elite player. The fact that he didn’t have international aspirations, and was content playing club cricket, upset me, but I realise now that being satisfied rather than ambitious is not necessarily a bad thing.

My Uncle Patrick, who also enjoyed first-class success but didn’t pursue a career in cricket, once summed it up this way: ‘Desire, hunger, focus, call it what you will, is the key to success, at least as much as talent. I had a bit of the latter and bugger all of the former.’

Dad had a different mantra which he drummed into me every day before school: ‘Whatever you do, do it well’. It seemed such a simple statement and yet it can be interpreted in so many different ways. To me, doing your best meant perfectionism, and that would bring with it a form of paralysis.

I was driven to succeed like a maniac. I wanted to be worked harder and harder in training and dreamed of having a fitness trainer, full-time coach and a nutritionist when every other teenager was shoving junk food down their gullet. I created my own expectation and pressures – a Tiger Woods, at least in my dedication and thirst for improvement.

Dad was always my greatest supporter, throwing balls for me for hours and teaching me the basics of the game; encouraging but never over the top as some parents of promising youngsters can become. But in my extreme world, his level of support wasn’t enough. Why couldn’t he be the same as Tiger Woods’ father, Earl? Why wouldn’t he wake me up at 5 a.m. and make me train and practise?

The reason was simple. What I wanted wasn’t normal, and in hindsight it wasn’t healthy.

There was one other person who bore the brunt of my obsessive childhood practice. Dad was trying to run a business from home and couldn’t respond to all my demands for attention. That task fell to our gardener, Mboneni Ngcobo, and I thank him from the bottom of my heart for his patience and perseverance.

The family home in the suburb of Berea had a huge garden built over three levels, and Dad had given over the second tier to cricket; a flat strip where someone could bowl to me, sometimes for hours. Mboneni had never played cricket so he couldn’t bowl, as such, but knew how to throw the assegai, the Zulu spear, so he adapted the technique to throw the cricket ball – a human bowling machine if you will.

There were days that he pleaded with me to give him a break; either his arm was sore or he had work to do around the garden. Dad would insist that I leave him alone and concentrate on homework, but I’d last a few minutes before I was back pestering Mboneni, who usually obliged.

Dad eventually erected nets to try and stop the increasing number of broken windows around the house and even bought a bowling machine and taught Mboneni how to use it. That only encouraged me of course, and the garden got even less attention.

*

The first outward signs of my battle with anxiety were simple things endured by many kids, like being wary of staying overnight at a friend’s house and phoning my mother in the middle of the night to come and get me. But by the age of ten I wasn’t being invited at all. There was too much drama when I was around and I wasn’t much fun for the others. It cut me deeply because, despite my insistence that I didn’t care, the truth was I was desperate to be liked and couldn’t understand why I was actively disliked.

My mother despaired at my struggles which, ironically, were compounded by the success I was having on the sporting field. You would think that I might have been popular but, instead, I was ostracised and bullied. I was an outsider because I was different – highly sensitive with emotions that I found difficult to manage.

Mum’s worst moment came one year at the school athletics carnivals. She was in the stands with the other parents and recalls me bouncing up to her with yet another trophy to keep while I ran off to compete in the next event – running, jumping or throwing – which I invariably won to deliver yet another trophy or ribbon. Mum wanted to be proud but there were no kind words from those around her, just barbed stares of resentment that my success had somehow come at the cost of their own sons. Finally, embarrassed, she slunk away with the trophies which she put in the boot of the car.

Things would get worse towards the end of my primary school days at Clifton Preparatory School which has an annual cricket tour to England, where I would play in front of Grandad.

In the weeks leading up to our departure I broke down, shaking in fear and sleeping in Mum’s bed. The idea of going to England on my own played to my fragility about separation. Of course I wanted to go, but rather than being just nervous, as my teammates might have been, I was paralysed with fear of being away from my parents and home. It was only solved when Dad agreed to come along.

I clearly had serious problems but despite my pleading with them to enrol me at the local high school, Mum and Dad insisted on sending me to a prestigious boarding school. I managed to convince them to delay the move by repeating my final year at Clifton because my birthday was late in the school year, but the problem was simply delayed and re-emerged a year later. This time I relented.

The school was Hilton College at Pietermaritzburg, barely an hour from Durban and yet it felt to me as if I was on the other side of the world – and alone. I remember my first day as one of nausea and being paralysed with fear; curled up on the floor in a foetal position. It felt in a way like vertigo; the sense that you were falling and had to drop to your knees and find something to grip tightly. The logic part of my brain knew that I was safe but my emotions convinced me that I was in danger. It didn’t improve and I lasted just seven months before the principal phoned my parents who agreed to take me out and enrol me at Durban High School, a ten-minute walk from home.

It seems strange that in the midst of my anguish I was chosen as captain of Hilton’s cricket side. As incongruous as it seems, the boy who cried himself to sleep every night and even talked about suicide was the same boy who captained the cricket team with confidence, winning every match that summer, not just as its star player but as the on-field leader. I felt I had so much to offer and it forced me to be a bigger person and to think of others rather than worry about myself. It is a theme that would repeat itself many times over the years and one of my biggest regrets.

*

If you scan the honour roll at Durban High School then you understand the depth of its cricketing roots. There have been thirty-six students over the years who have gone on to play for South Africa, including the great Barry Richards who, as it happens, once had a coaching session with my grandad, an experience he said had had ‘a stupendous effect on me’.

DHS was my dream cricket school, where I could watch batting practice from the classroom window and where my dreams of excellence were not dismissed but encouraged. But there was a catch. I had been top dog at Clifton and Hilton, clearly the best player who held the team together, but that would not be the case when I arrived at DHS. In this breeding ground of excellence there would be others. Rivals to my plans.

Two of them were classmates. Hashim Amla and Imraan Khan would also go on to play international cricket. Imraan and I had met a few years earlier when we played together for various Natal underage teams. He and I were the best players at that age, but by the time we reached high school, Hashim, who had grown up in the sugar cane town of Tongaat just north of Durban, had surpassed us both. Hashim’s immense talents were spotted by the KwaZulu-Natal Cricket Union when it began expanding its catchment areas for youngsters into rural towns.

I was standing with Dad one day, watching Hashim bat in the nets. He struck the ball with such ease and with the power of an adult. I was torn, jealous that someone was better than me but in awe of his abilities. The latter feeling won out: ‘Put some money on Hashim,’ I told Dad. ‘He will captain South Africa one day.’ It was only a week or so later that I was batting with Hashim in a school match and stupidly ran him out. I remember the anguished look on his face as he walked past me back towards the pavilion. I felt terrible, as if I had let down a legend of the game rather than a fellow junior. It didn’t help that I made 80 or so that day.

Hashim has gone on to a stellar career, not just as a great player but as an ambassador to the game. A man with strong religious convictions, he is softly spoken and has a great sense of humour. We weren’t close as kids, partly because I wanted to be as good as him. I had a habit of keeping to myself, but we always had a lot of respect for one another. We have reminisced a few times over the years, usually over a curry at my place when I was playing at Somerset, and I realise how important it was to have someone like him as a contemporary and someone I had to match or better.