6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

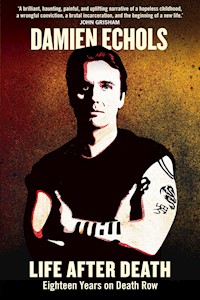

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2014 CWA NON-FICTION DAGGER An instant New York Times bestseller, Life After Death is an agonizing first-hand account of an innocent man living on Death Row. It is destined to be an explosive classic of memoir. In 1993, teenagers Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley, Jr. - who have come to be known as the West Memphis Three - were arrested for the murders of three eight-year-old boys in Arkansas. The ensuing trial was marked by tampered evidence, false testimony, and public hysteria. Baldwin and Misskelley were sentenced to life in prison, while eighteen-year-old Echols, deemed the 'ringleader,' was sentenced to death. Over the next two decades, the three men became known worldwide as a symbol of wrongful conviction and imprisonment, with thousands of supporters and many notable celebrities calling for a new trial. In a shocking turn of events, all three men were released in August 2011. Now Echols shares his story in full - from abuse by prison guards and wardens, to portraits of fellow inmates and deplorable living conditions, to the incredible reserves of patience and perseverance that kept him alive and sane while incarcerated for nearly two decades.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

First published in the United States of America in 2012 by Blue Rider Press, an imprint of the Penguin Group Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Damien Echols Publishing, 2012

The moral right of Damien Echols to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 122 7

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 123 4

Atlantic Books An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

for Lorri

Silently I sit by

Watching men pace their cells

Like leopards

Biting their nails

With furrowed brows

The scene speaks for itself

— DAMIEN ECHOLS,

VARNER SUPER MAXIMUM

SECURITY UNIT,

GRADY, ARKANSAS

AUTHOR’S NOTE

What you’re about to read is the result of many things I’ve written in the past twenty years, including parts of a short memoir self-published in 2005. I was sent to Death Row in 1994, and almost immediately I began keeping a journal. I didn’t date most of my writings, it was simply too painful to look at days, months, years slipping past, the reality outside just beyond my reach. Many of the journals I kept are gone, stolen or destroyed when guards raided the barracks—anything personal or creative is a prime target in a shakedown. I’ve included as much as I could of what remained, and I hope the subject or context of these entries is helpful in placing some of them. Others don’t need a time stamp. The conditions I have described in the prison system—the sadness, horror, and sheer absurdity that I’ve seen many human beings subjected to—will not have changed by the time you hold this book in your hands.

PREFACE

Saint Raymond Nonnatus, never was it known that anyone who implored your help or sought your intercession was left unaided. To you I come, before you I stand. Despise not my petitions, but in your mercy hear and answer me.”

Saint Raymond Nonnatus is one of my patron saints. I would be willing to bet that most people have no idea that he is the patron saint of those who have been falsely accused. I like to think that means I have a special place in his heart, because you can’t get much more falsely accused than I have been. So me and old Raymond have struck a bargain. If he helps me out of this situation, then I will travel to all the world’s biggest cathedrals and leave roses and chocolate at the feet of every one of his statues that I can find. You didn’t know saints liked chocolate? Well then, that’s one thing you’ve already learned, and we’re just getting started!

I have three patron saints in all. You may be wondering who the other two are, and how a foul-mouthed sinner such as myself was blessed with not one but three saints to watch over him. My second patron saint is Saint Dismas. He’s the patron saint of prisoners. So far he’s done his job and watched over me. I’ve got no complaints there. So, what deal do Saint Dismas and I have? Just that I do my part by going to Mass every week in the prison chapel, unless I have a damn good reason not to.

My third patron saint is one I’ve had reason to talk with many times in my life. Saint Jude, patron saint of desperate situations. I’d say being on Death Row for something I didn’t do is pretty desperate. And what does Saint Jude get? He just likes to watch and see what ridiculous predicament I find myself in next.

If I start to believe that the things I write cannot stand on their own merit, then I will lay down my pen. I’m often plagued by thoughts that people will think of me only as either someone on Death Row or someone who used to be on Death Row. I grow dissatisfied when I think of people reading my words out of a morbid sense of curiosity. I want people to read what I write because it means something to them—either it makes them laugh, or it makes them remember things they’ve forgotten and that once meant something to them, or it simply touches them in some way. I don’t want to be an oddity, a freak, or a curiosity. I don’t want to be the car wreck that people slow down to gawk at.

If someone begins reading because they want to see life from a perspective different from their own, then I would be content. If someone reads because they want to know what life looks like from where I stand, then I will be happy. It’s the ghouls that make me feel ill and uneasy—the ones who care nothing for me, but interest themselves only in things like people who are on Death Row. Those people give off the air of circling vultures, and there’s something unhealthy about them. They wallow in depression and their lives tend to follow a downward trend. Their spirits seem mostly dead, like larvae festering on summer-day roadkill. I want nothing to do with that energy. I want to create something of lasting beauty, not a grotesque freak show exhibit.

Writing these stories is also a catharsis for me. It’s a purge. How could a man be subjected to the things I have been and not be haunted? You can’t send a man to Vietnam and not expect him to have flashbacks, can you? This is the only means I have of clearing the trauma out of my psyche. There are no hundred-dollar-an-hour therapy sessions available for me. I have no need of Freud and his Oedipal theories; just give me a pen and paper.

I’ve witnessed things in this place that have made me laugh and things that have made me cry. The environment I live in is so warped that incidents that would become legends in the outside world are forgotten the next day. Things that would show up in newspaper headlines in the outside world are given no more than a passing glance behind these filthy walls. When I first arrived at the Tucker Maximum Security Unit located in Tucker, Arkansas, in 1994, it blew my mind. After being locked down for more than ten years, I’ve become “penitentiary old,” and the sights no longer impress me as much. To add the preface of “penitentiary” to another word redefines it. “Penitentiary old” can mean anyone thirty or older. “Penitentiary rich” means a man who has a hundred dollars or more. In the outside world a thirty-year-old man with a hundred dollars would be considered neither old nor rich—but in here it’s a whole ’nother story.

The night I arrived on Death Row I was placed in a cell between the two most hateful old bastards on the face of the earth. One was named Jonas, the other was Albert. Both were in their late fifties and had seen better days physically. Jonas had one leg, Albert had one eye. Both were morbidly obese and had voices that sounded like they had been eating out of an ashtray. These two men hated each other beyond words, each wishing death upon the other.

I hadn’t been here very long when the guy who sweeps the floor stopped to hand me a note. He was looking at me in a very odd way, as if he were going to say something but then changed his mind. I understood his behavior once I opened the note and began reading. It was signed “Lisa,” and it detailed all the ways in which “she” would make me a wonderful girlfriend, including “her” sexual repertoire. This puzzled me, as I was incarcerated in an all-male facility and had seen no one who looked like they would answer to the name of Lisa. There was a small line at the bottom of the page that read, “P.S. Please send me a cigarette.” I tossed the note in front of Albert’s cell and said, “Read this and tell me if you know who it is.” After less than a minute I heard a vicious explosion of cursing and swearing before Albert announced, “This is from that old whore, Jonas. That punk will do anything for a cigarette.” Thus Lisa turned out to be an obese fifty-six-year-old man with one leg. I shuddered with revulsion.

It proved true that Jonas would indeed do anything for cigarettes. He was absolutely broke, with no family or friends to send him money, so he had no choice but to perform tricks in order to feed his habits. He was severely deranged, and I believe he also liked the masochism it involved. For example, he once drank a sixteen-ounce bottle of urine for a single, hand-rolled cigarette. I’d be hard-pressed to say who suffered more—Jonas, or the people who had to listen to him gagging and retching as it went down. Another time he stood in the shower and inserted a chair leg into his anus as the entire barracks looked on. His reward was one cigarette. These weren’t even name-brand cigarettes, but generic, hand-rolled tobacco that cost about a penny each.

As I’ve hinted, Jonas was none too stable in the psychological department. This is a man whose false teeth were painted fluorescent shades of pink and purple, and who crushed up the lead in colored pencils in order to make eye shadow. The one foot he had left was ragged and disgusting, with nails that looked like corn chips. One of his favorite activities was to simulate oral sex with a hot sauce bottle. He once sold his leg (the prosthetic one) to another inmate, then told the guards that the inmate had taken it from him by force. The inmate got revenge by putting rat poison in Jonas’s coffee. The guards figured out something was wrong when Jonas was found vomiting blood. He was the single most reviled man on Death Row, hated and shunned by every other inmate. A veritable prince of the correctional system. You don’t encounter many gentlemen in here, but Jonas stood out even in this environment.

I do not wish to leave you with the impression that Albert was a gem, either. He was constantly scheming and scamming. He once wrote a letter to a talk show host, claiming that he would reveal where he had hidden other bodies if the host would pay him a thousand dollars. Being that he had already been sentenced to death in both Arkansas and Mississippi, he had nothing to lose. When he was finally executed, he left me his false teeth as a memento. He left someone else his glass eye.

For all the insanity that takes place inside the prison, it’s still nothing compared with the things you see and hear in the yard. In 2003, all Arkansas Death Row inmates were moved to a new “Super Maximum Security” prison in Grady, Arkansas. There really is no yard here. You’re taken, shackled of course, from your cell and walked through a narrow corridor. It leads to the “outside,” where without once actually setting foot outside the prison walls, you’re locked inside a tiny, filthy concrete stall, much like a miniature grain silo. There is one panel of mesh wire about two feet from the top of one wall that lets in the daylight, and you can tell the outdoors is beyond, but you can’t actually see any of it. There’s no interaction with other prisoners, and you’re afraid to breathe too deeply for fear of catching a disease of some sort. I went out there one morning, and in my stall alone there were three dead and decaying pigeons, and more feces than you can shake a stick at. The smell reminds me of the lion house at the Memphis Zoo, which I would visit as a child. When you first enter you have to fight against your gag reflex. It’s a filthy business, trying to get some exercise.

Before we moved here we had a real yard. You were actually outside, in the sun and air. You could walk around and talk to other people, and there were a couple of basketball hoops. Men sat around playing checkers, chess, dominoes, or doing push-ups. A few would huddle in corners smoking joints they bought from the guards.

I’d been there less than two weeks when one day on the yard my attention was drawn to another prisoner who had been dubbed “Cathead.” This unsavory character had gained the name because that’s exactly what he looked like. If you were to catch an old, stray tomcat and shave all the fur off its head you would be looking at the spitting image of this fellow. Cathead was sitting on the ground, soaking up the sun and chewing a blade of grass that dangled from the corner of his mouth. He was staring off into space as if absorbed in profound thought. I had been walking laps around the yard and taking in the scenery. As I passed Cathead for the millionth time he looked up at me (actually it was more like he was seeing some other place, but his head turned in my direction) and he asked, “You know how you keep five people from raping you?” I was caught off guard, as this was not a question I had ever much considered, or thought I’d ever be called upon to answer. I looked at this odd creature, waiting for the punch line to what I was hoping was a joke. He soon answered his own question: “Just tighten your ass cheeks and start biting.” I was horrified. He was dead serious, and seemed to think he was passing on a bit of incredibly well-thought-out wisdom. The only things going through my mind were What kind of hell have Ibeen sent to? Is this what passes for conversation here? I quickly went back to walking laps and left Cathead to his ponderings.

Prison is a freak show. Barnum and Bailey have no idea what they’re missing out on. I will be your master of ceremonies on a guided tour of this small corner of hell. Prepare to be dazzled and baffled. If the hand is truly quicker than the eye, you’ll never know what hit you. I know I didn’t.

CONTENTS

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

EPILOGUE

One

My name is Damien Echols, although it wasn’t always. At birth I was different in both name and essence. On December 11, 1974, when I came into the world, I was named Michael Hutchison at the insistence of my father, Joe Hutchison. My mother, Pam, had a different name in mind, but my father would hear none of it. They argued about it for years afterward.

The hospital where I was born still stands in the small run-down town of West Memphis, Arkansas. It’s the same hospital where my maternal grandmother, Francis Gosa, died twenty years later. As a child I was jealous of my sister, Michelle, who was lucky enough to be born, two years after me, across the bridge in Memphis, Tennessee. In my youth Memphis always felt like home to me. When we crossed the bridge into Tennessee I had the sensation of being where I belonged and thought it only right that I should have been the one born there. After all, my sister didn’t even care where she was born.

My mother and grandmother were both fascinated by the fact that after I had been delivered and the doctor had discharged my mother from the hospital, I was placed in a Christmas stocking for the short journey home. They kept the stocking for years, and I had to hear the story often. I found out later that hospitals all over the country do the same thing for every baby born in the month of December, but this fact seemed to be lost on my mother, and it marked the beginning of a lifetime of denial. After saving the stocking as if it were a valuable family heirloom for seventeen years, it was unceremoniously left behind in a move that was less than well planned.

Other than the stocking I had only one memento saved from childhood—a pillow. My grandmother gave it to me the day I left the hospital, and I slept on it until I was seventeen years old, when it was left behind in the same ill-fated move. I could never sleep without that pillow as a child, as it was my security blanket. By the end it was nothing more than a ball of stuffing housed in a pillowcase that was rapidly disintegrating.

Being born in the winter made me a child of the winter. I was truly happy only when the days were short, the nights were long, and my teeth were chattering. I love the winter. Every year I long for it, look forward to it, even though I always feel as if it’s turning me inside out. The beauty and loneliness of it hurts my heart and carries with it all the memories of every winter before. Even now, after having been locked in a cell for years, at the coming of winter I can still close my eyes and feel myself walking the streets as everyone else lies in bed asleep. I remember how the ice sounded as it cracked in the trees every time the wind blew. The air could be so cold that it scoured my throat with each breath, but I would not want to go indoors and miss the magick of it. I have two definitions for the word “magick.” The first is knowing that I can effect change through my own will, even behind these bars; and the other meaning is more experiential—seeing beauty for a moment in the midst of the mundane. For a split second, I realize completely and absolutely that the season of winter is sentient, that there is an intelligence behind it. There’s a tremendous amount of emotional pain that comes with the magick of winter, but I still mourn when the season ends, like I’m losing my best friend.

The first true memories I have of my life are of being with my grandmother Francis, whom I called Nanny. Her husband, Slim Gosa, had died about a year before. I recall him vaguely: he drove a Jeep, and I remember him being very nice to me. He died the day after my birthday. Nanny wasn’t my biological grandmother; Slim had had an affair with a Native American woman, who gave birth to my mother. My grandmother, unable to have her own children, raised my mother as her own. My parents, sister, and I had been living in different places in the Delta region—the corner where Arkansas, Tennessee, and Mississippi meet. After my sister was born, my mother felt she couldn’t take care of two children. So Nanny and I lived in a small mobile home trailer in Senatobia, Mississippi. I remember the purple and white trailer sitting on top of a hill covered with pine trees. We had two large black dogs named Smokey and Bear, which we had raised from puppies. One of my earliest memories was of hearing the dogs barking and lunging against their chains like madmen as Nanny stood in the backyard with a pistol, shooting at a poisonous snake. She didn’t stop shooting, even as the snake slithered its way under the huge propane tank in the backyard. Only in hindsight, years later, did I realize she would have blown us all straight to hell if she had hit the tank. At the time I was so young that I viewed the entire scene with nothing but extreme curiosity. It was the first time I had ever seen a snake, and it was combined with the additional spectacle of my grandmother charging out the back door, blazing away like a gunslinger.

My grandmother worked as a cashier at a truck stop, so during the day she left me at a day care center. I can remember it only because it was horrific. I remember being dropped off so early in the morning that it was still dark, and being led to a room in which other children were sleeping on cots. I was given a cot and told that I should take a nap until Captain Kangaroo (my favorite television show) came on. The problem was that I could not, under any circumstances, go to sleep without my pillow and security blanket. I began to scream and cry at the top of my lungs, tears running down my face. It awakened and frightened every other child in the dark room, so that within a few seconds everyone was crying and screaming while frantic day care workers ran from cot to cot in an attempt to find out what was wrong. By the time they got everyone quiet and dried all the tears it was time for Captain Kangaroo and I was quickly absorbed into the epic saga of Mr. Green Jeans and a puppet moose that lived life in perpetual fear of being pelted with a storm of Ping-Pong balls. After that day, my grandmother never forgot to send my pillow with me.

She would recite the same rhyme every night as she tucked me into bed. She’d say, “Good night, sleep tight, don’t let the bedbugs bite.” I had no idea what a bedbug was, but it seemed pretty obvious from the rhyme that they were capable of inflicting pain. As she closed the door and left me in total darkness, all I could think about were those nocturnal monster insects. I never formed a definite mental image of what they looked like, and somehow that vagueness only made the fear worse. The closest I could come to picturing them was something like stinkbugs with shifty eyes and an evil grin. No matter how tired I was when she tucked me in, the mention of those bugs would wake me up like a dose of smelling salts.

There was something else Nanny used to say that made my hair stand on end. Late at night we would be watching television with all of the lights in the house turned off. The only illumination was the flickering blue glow of the TV screen. She would turn to me and say, “What sound does a scarecrow make?” My eyes would bulge like Halloween caricatures as she looked at me grimly and said, “Hoo! Hoo!” I had no idea what it meant, or why a scarecrow would make the sound of an owl, but for the rest of my life I would never think of one without the other. Later in life those images began to feel like home to me and they brought me comfort. They became symbols of the purest kind of magick, and reminded me of a time when I was safe and loved. There’s something about it that can never be put into words, but the sight of a scarecrow now makes my heart swell. It makes me want to cry. The memory of those jovial October scarecrows on southerners’ front porches takes me to some other place. Now the scarecrow symbolizes a kind of purity.

Every so often, sitting here in solitary confinement, I need to become something else. I need to transform myself and gain a new perspective on reality. When I do, everything must change—emotions, reactions, body, consciousness, and energy patterns. I turned to Zen out of desperation. I had been through hell, traumatized, and sent to Death Row for a crime I did not commit. My anger and outrage were eating me alive. Hatred was growing in my heart because of the way I was being treated on a daily basis. The cleaner you are, the more light that can shine through you. Clear out all the bad, and the current will float through like light through a windowpane. It’s a process I have pushed myself through many times. Each day that I wake up means that I’m one day closer to new life. I can feel the years of accumulated programming and trauma melting away from my body, leaving behind a long-remembered cleanness. I usually have at least a vague idea of what I hope to accomplish or experience—create an art project, explore other realms of consciousness—but this time I’m blindly flowing to wherever the current carries me. I feel younger than I have in the past decade, and memories I had long forgotten are now once again within touching distance.

In the movies it’s always the other prisoners you have to watch out for. In real life, it’s the guards and the administration. They go out of their way to make your life harder and more stressful than it already is, as if being on Death Row were not enough. They can send a man to prison for writing bad checks and then torment him there until he becomes a violent offender. I didn’t want these people to be able to change me, to touch me inside and turn me as rotten and stagnant as they were. I tried out just about every spiritual practice and meditative exercise that might help me to stay sane over the years.

I’ve lost count of how many executions have taken place during my time served. It’s somewhere between twenty-five and thirty, I believe. Some of those men I knew well and was close to. Others, I couldn’t stand the sight of. Still, I wasn’t happy to see any of them go the way they did.

Many people rallied to Ju San’s cause, begging the state to spare his life, but in the end it did no good. He had committed such a heinous crime. Frankie Parker had been a brutal heroin addict who killed his former in-laws and held his ex-wife hostage in an Arkansas police station. Over the years he had become Ju San, an ordained Rinzai Zen Buddhist priest with many friends and supporters. On the night of his execution in 1996, shortly after he was pronounced dead, his teacher and spiritual adviser was allowed to walk down Death Row and greet the convicts. It was the first time that a spiritual adviser had been permitted to speak to inmates after an execution. He told us what Frankie’s last word was, what he ate for a last meal, and he described his execution to us.

I had been watching the news coverage of Ju San’s death when someone stepped in front of my door. I turned to see a little old bald man in a black robe and sandals, clutching a strand of prayer beads. He had these wild white eyebrows that were so out of control they looked like small horns. He practically had handlebar mustaches above his eyes. He seemed intense and concentrated as he introduced himself. A lot of Protestant preachers come through Death Row, but they all seem to think themselves better than us. You could tell it by the way most of them didn’t even bother to shake hands. Kobutsu wasn’t like that at all. He made direct, unwavering eye contact and seemed to be genuinely pleased to meet me. It had been his personal mission to do everything he could to help Ju San, and he was pretty torn up over the execution. Before he left, he said I should feel free to write to him at any time. I took him up on that offer.

He and I began corresponding, and I eventually asked him to become my teacher. He accepted. Kobutsu is a paradox: a Zen monk who chain-smokes, tells near-pornographic jokes, and always has an appreciative leer for the female anatomy. He’s a holy man, carnival barker, anarchist, artist, friend, and asshole all rolled up in one robe. I immediately took a shine to him.

Kobutsu would send me books about the old Zen masters, different Buddhist practices, and small cards to make shrines out of. He returned not long after Ju San’s execution to perform a refuge ceremony for another Death Row inmate, and I was allowed to participate in the ceremony. Refuge is the Buddhist equivalent of baptism. It’s like declaring your intention to follow this path, so that the world witnesses it. It was a beautiful ceremony that stirred something in my heart.

Under Kobutsu’s tutelage, I began sitting zazen meditation on a daily basis. Zazen meditation entails sitting quietly, focusing on nothing but your breath, moving in and out. At first it was agony to have to sit still and stare at the floor for fifteen minutes. Over time I became more accustomed to it, and managed to increase my sitting time to twenty minutes a day. I put away all reading material except for Zen texts and meditation manuals. I’d read nothing else for the next three years.

About six months after the other prisoner’s refuge ceremony, Kobutsu returned to perform it for me. The magick this ritual held within it increased my determination to practice tenfold. I started every day with a smile on my face, and not even the guards got to me. I think it was a little unsettling to them to strip-search a man who smiled at you through the whole ordeal.

Kobutsu and I continued to correspond through letters and also talked on the phone. His conversations were a mixture of encouragement, instruction, nasty jokes, and bizarre tales of his latest adventures. Through constant daily practice, my life was definitely improving. I even constructed a small shrine of paper Buddhas in my cell to give me inspiration. I was now sitting zazen meditation for two hours a day and still pushing myself. I’d not yet had that elusive enlightenment experience that I’d heard so much about, and I desperately wanted it.

One year after my refuge ceremony, Kobutsu decided it was time for my Jukai ceremony. Jukai is lay ordination, where one begins to take vows. It’s also where you are renamed, to symbolize taking on a new life and shedding the old one. Only the teacher decides when you are ready to receive Jukai.

My ceremony would be performed by Shodo Harada Roshi, one of the greatest living Zen masters on earth. He was the abbot of a beautiful temple in Japan, and would fly to Arkansas for this occasion. I anticipated the event for weeks beforehand, so much that I had trouble sleeping at night. The morning of the big event I was up before dawn, shaving my head and preparing to meet the master.

Kobutsu was first in line through the door. I could see the light reflecting off his freshly shaved pink head. I also noticed he had abandoned his usual Japanese sandals in favor of a pair of high-top Converse tennis shoes. It was odd to see a pair of sneakers protruding from under the hem of a monk’s robe. Behind him walked Harada Roshi. He wore the same style robe as Kobutsu, only it was in pristine condition. Kobutsu tended to have the occasional mustard stain on his, and didn’t seem to mind one bit.

Harada Roshi was small and thin, but had a very commanding presence. Despite his warm smile, there was something about him that was very formal in an almost military sort of way. I believe the first word that came to mind when I saw him was “discipline.” He seemed disciplined beyond anything a human could achieve, and it greatly inspired me. To this day I still strive to have as much discipline about myself as Harada Roshi. Beneath his warmth and friendliness was a will of solid steel.

We were all led into a tiny room that served as Death Row’s chap el. Harada Roshi talked about the difference between Japan and America, about his temple back home, and about how few Asians came to learn at the old temple now; it was mostly Americans who wanted to learn. His voice was low, raspy, and rapid-fire. Japanese isn’t usually described as a beautiful language, but I was entranced by it. I dearly wished I could make such poetic, elegant-sounding words come from my own mouth.

Harada Roshi set up a small altar to perform the ceremony. The altar cloth was white silk, and on it was a small Buddha statue, a canvas covered with calligraphy, and an incense burner. We all dropped a pinch of the exotic-smelling incense into the burner as an offering, and then opened our sutra books to begin the proper chants. Kobutsu had to help me turn the pages of my book because the guards made me wear chains on my hands and feet. During the course of the ceremony I was given the name Koson. I loved that name and all it symbolized, and scribbled it everywhere. I was also presented with my rakusu.

A rakusu is made of black cloth, and is suspended from your neck. It covers your hara, which is the energy center about two finger-widths below your belly button. It has two black cloth straps and a wooden ring/buckle. It’s sewn in a pattern that looks like a rice paddy would if viewed from the air. It represents the Buddha’s robe. This is the only part of my robe the administration would allow me to keep inside the prison. On the inside, Harada Roshi had painted beautiful calligraphy characters that said, “Great effort, without fail, brings great light.” It was my most prized possession until the day years later when the prison guards took it from me.

The canvas on the altar was also given to me. Its calligraphy translates to “Moonbeams pierce to the bottom of the pools, yet in the water not a trace remains.” I proudly put it on display in my cell.

I ventured into the realm of Zen to gain a handle on my negative emotional states, which I had learned to control to a great extent, but I now approached my practice in a much more aggressive manner. Much like a weight lifter, I continued to pile it on. On weekends I was now sitting zazen meditation for five hours a day. My prayer beads were always in my hand as I constantly chanted mantras. I practiced hatha yoga for at least an hour a day. I became a vegetarian. Still, I did not have a breakthrough Kensho experience. Kensho is a moment in which you see reality with crystal-clear vision, what a lot of people refer to as “enlightenment.” I didn’t voice my thoughts out loud, but I was beginning to harbor strong suspicions that Kensho was nothing more than a myth.

A teacher of Tibetan Buddhism started coming to the prison once a week to instruct anyone interested. I attended these sessions, which were specifically tailored to be of use to those on Death Row. One practice I and another inmate were taught is called Phowa. It consists of pushing your energy out through the top of your head at the moment of death. It still did not bring about that life-changing moment I was in search of.

Two

My memory really starts to come together and form a narrative once I started school. I can still remember every teacher I ever had, from kindergarten through high school.

My parents, sister, and I moved into an apartment complex called Mayfair in 1979, as far as I recall. We had an upstairs apartment in a long line of identical doors. When I went out to play, I could find my way back home only by peeking in every window until I saw familiar furnishings. My grandmother also moved into an apartment in the complex, one row behind us. This was the year I started kindergarten, and I remember it well.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!