Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Umbria Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

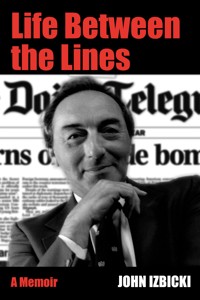

John Izbicki has an exciting story to tell. Berlin-born, he lived through the horrors of Nazi persecution and, on the day after his eighth birthday, he witnessed the Kristallnacht, and the smashing of his parents' shop windows. On the day Germany invaded Poland and Berlin experienced its first wartime blackout, the Izbickis escaped to Holland and from there on to England. The author describes what it feels like to have been a refugee, unable to speak or understand a single word of English, and how he was persuaded by a kind policeman to change his name from Horst to John. He also leads the reader along the remarkable journey he travelled from school to university, the first of his family to enter higher education, and through his adventurous time as a commissioned army officer during two years of national service spent in Egypt and Libya. But the best part of his life was yet to come when this young refugee decided to make journalism his profession. The boy who, not that many years earlier, could speak not a word of English, became the distinguished education correspondent of the country's leading quality newspaper, the Daily Telegraph. After eighteen years in that responsible position, he was sent to Paris to head the Telegraph's office there. When he left the newspaper to join the Committee of Directors of Polytechnics, he played a leading part in transforming the country's polytechnics into its 'new universities'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 794

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Copyright © John Izbicki 2012

John Izbicki has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover image by Paul Izbicki

Umbria Press, 2 Umbria Street, London SW15 5DPwww.umbriapress.co.uk

Printed and bound by Ashford Colour Press Ltd, Gosport

Paperback ISBN 978-0-9541275-7-2

I dedicate this book to my son, Paul, my stepson and stepdaughter Patrick and Anna, my grandchildren, Tyler and Chloe and my step-granddaughter, Robyn

And I should also like to dedicate it to the memory of the many who perished in the holocaust.

CONTENTS

PREFACE BY CHARLES MOORE

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1 KRISTALLNACHT

CHAPTER 2 ESCAPE

CHAPTER 3 A NEW LIFE

CHAPTER 4 MOVE TO MANCHESTER

CHAPTER 5 PEACE

CHAPTER 6 ON CAMPUS

CHAPTER 7 RETURN TO GERMANY

CHAPTER 8 NATIONAL SERVICE

CHAPTER 9 REAL WORK BEGINS

CHAPTER 10 PARIS LOVES

CHAPTER 11 MY NAKED HEROINE

CHAPTER 12 TAKEOVER

CHAPTER 13 THE TORYGRAPH

CHAPTER 14 THE TORYGRAPH (2)

CHAPTER 15 ON TO EDUCATION

CHAPTER 16 THE THATCHER YEARS

CHAPTER 17 SADNESS AND LIGHT

CHAPTER 18 BACK TO PARIS

CHAPTER 19 FAREWELL SQUABBLES

CHAPTER 20 FROM POLY TO UNI

CHAPTER 21 HEADHUNTED AT 62

CHAPTER 22 EPILOGUE

INDEX

PREFACE

When I joined the Daily Telegraph as a young reporter in 1979, the paper had a reputation for being stuffy and staid. The odd thing was that no words could have been less appropriate for the journalists who worked there. The place was a charming madhouse of genius, drunkenness, wit and eccentricity.

Even in this gallery, though, no figure was more exotic than that of John Izbicki (though he was, I hasten to add, sober). Snappily dressed, with attractive dark looks and a sort of mock courtliness in his manner, he looked like the compere of a variety show. It was typical of the unexpectedness of the paper that John was, in real life, its education correspondent. It surprised me that this was his job. It did not surprise me to hear that his legendary charm had persuaded Margaret Thatcher, then Education Secretary, to join him after a dance to admire Scarborough beach in the moonlight.

John was one of those clever men who, while always busy, always have time to talk, so I learnt a good deal of the lore and language of Fleet Street from him. But when one works with people, one tends not to ask them their life history; and so I never knew John’s – until now. It is a tragic, touching, comic and inspiring tale.

From the horrible moment on the Kristallnacht in 1938 when the Nazis smashed his father’s Berlin haberdashery shop while young Horst (John) hid, through his life as refugee, as a foreign correspondent, as a saviour of the Open University and as a specialist reporter, to his retirement in rural Kent, John Izbicki vividly takes us through the extraordinary changes and chances of the 20th century.

For me, two things stand out. One is the unique contribution made to the life of this country by the generation of Jews of whom John is a leading example. The other is that this book explains to the reader why newspapers are – or should I say were? – fun. His has been a life well lived, and here it is, well told.

Charles Moore

INTRODUCTION

For many years, I have been asked and encouraged to pen my memoirs. People, whether they were my readers, my professional contacts or simply my friends, told me that I had a story to tell – the story of a little Jewish refugee boy who came to England on the day the Second World War was declared, unable to speak a single word of English, and who became the education correspondent (editor) of the Daily Telegraph and the head of its Paris office, and later helped the country’s polytechnics become universities. I hope you will find the book filled with enjoyable anecdotes, humour and pathos and, yes, sadness.

My thanks go out to June, my wife, who not only showed great patience during the many months I sat closeted in my study to write these pages, but who also helped by checking for literals and the odd (I hope very odd) grammatical error.

My thanks are also extended to Demitri Coryton, editor and proprietor of Education Journal, the informative monthly magazine, for which I have been contributing regular columns, and who urged me to write these memoirs.

Now turn the page – and enjoy!

John Izbicki

Horsmonden, 2012

CHAPTER ONE:

KRISTALLNACHT

“Ich bin ein Jude!” “I am a Jew!” I shouted the words to the sky and they ricocheted from the tall houses and the trams that stood abandoned and silent in the middle of Invalidenstrasse, the street where I lived and which was now totally deserted. Nothing seemed to stir – except for me, a small five-year-old, who had woken from his afternoon nap and was making his way along the silent street. I had no idea why I was so completely alone or why the trams that usually clanked their way up and down the middle of this, one of Berlin’s busiest streets, were now motionless.

I did not see that there were men and women staring out from the shops that lined both sides of the road. All I knew was that, for the first time in my life, I was alone in this long and empty street and that I was free to shout words I would normally not even dare to whisper. To admit aloud and in public to being Jewish was just asking for trouble. I danced along the pavement and repeated with increasing glee: “I am a Jew....I am a Jew...I am...”

My happiness was cut short as a firm hand clasped my shoulder and dragged me away. “Be quiet! Be quiet at once!” my father blurted out as he pulled me the last few metres into the shop. “What the hell d’you think you’re doing, yelling like that. You’ll have us all arrested. Is that what you want? Well?”

But by now I was crying. The hot tears flowed freely. How could I tell him that I had only dared to confess my faith aloud because I was so alone and no one was listening? No one. By now my mother was already clasping me to her warm bosom. “Hush, hush, Horstchen. Don’t cry. Everything will be all right. Hush now.”

Only then did my father explain that there had been an air raid alarm. It was just a test but the whole of Berlin had to come to a standstill. Passengers were ordered off trams and took shelter in the nearest houses or shops until the all clear sounded. “You were not alone, Horst. Everyone could hear you from one end of the street to the other. They were all watching from their windows. You were very lucky that there wasn’t a police or Gestapo patrol. Otherwise...well, I don’t know what would have happened. But, believe me, it would not have done us any good.”

My father was a good, hardworking man, quick of temper but also quick to replace it with gentleness. He was born Luzer Ber Izbicki, the son of a baker, in Lenczyca, a small town in the Russian part of Poland in 1898. He was called up to fight with the Russian army during the Great War but, shortly after Armistice was declared, made his way out of the country on foot, tunnelling his way beneath the thick snow that enveloped the border and entering East Prussia. He earned his daily bread by doing odd jobs. His bronzed, handsome face and easygoing manner appealed to the German Hausfrau and work was readily offered. By the time he reached Kolberg, a popular north German seaside resort, he had managed to learn enough of the language to seek more permanent employment. A small shoe manufacturer was looking for designers. Luzer Ber knew nothing of shoes or art, but applied for the job and was promised a trial period. The job would start at the beginning of the month – two weeks away.

He spent every spare moment examining shoes in every Kolberg shop that sold them and studied books about them in the local reference library. By the time he started his job, he was able to draw the designs he had invented. They appealed to his new employer – and so did he. He managed to save enough to move out of the garret that had become his home and rent a small flat but lived mostly on bread, cheese and fruit, spending whatever was left on German books. These would go with him, tightly packed in a shoulder bag, wherever he went, accompanied by the hope that, somehow, the language would be transferred to him through some form of osmosis.

My father neither drank alcohol nor smoked. “A Russian officer once gave me three green cigars and I smoked them one after the other,” he would tell anyone who offered him a cigarette. “I was violently ill and haven’t touched tobacco since.” Only many years later would he sip at a glass of lager – to mark the first day of a family holiday. It became a tradition.

One Saturday, while drinking a coffee at a beach bar, he got talking to a pretty young woman at the next table. He and Hedwig Alexander went dancing or to a cinema or restaurant for more than a month and the relationship was on the point of becoming serious. Then Hedwig, Heti to her friends, took him home to meet Mum. Berta Alexander was a war widow. Hermann, her husband, had fought for the Fatherland and met his death by a bullet from a Russian rifle. Berta sold the small but lucrative cigar and cigarette factory he had started in the East Prussian town of Czersk and moved to Kolberg with her family of two daughters, Hedwig and Selma, and three sons, Isidor, Karl and Georg.

Heti’s introduction of Luzer to the Alexander family was a mistake on her part. But not as far as my future was concerned. It was in Berta’s comfortable home that he met Heti’s sister, Selma, and did not hesitate to ask her out. It took a while for Heti to forgive her younger sister, but forgive her she did. The Alexander family did not bear grudges. Selma had already had plenty of young admirers pestering her for a date, but this one, she felt, was different. For one thing, he had not tried to kiss her for weeks. And when they danced, he held her correctly, not too close. He brought flowers whenever he came to the house but presented them not to her but to her mother. He had learned German etiquette well and knew that patience was a virtue that would one day be rewarded.

They had met in the early part of 1921 and “courted” for nearly two years before Luzer popped the question. Selma accepted and her fiancé was welcomed into the Alexander family. It was not until 1925 that they were married at the local Kolberg synagogue, where Isidor, “Isi”, the eldest brother, replaced their war hero father in giving her away.

The honeymoon was brief and deliriously happy. Luzer had saved as much as he could from the wages he earned but there was not really enough to splash out. So they decided to spend a few days in Germany’s capital. It was on their second day in the cheap but clean Pension they had found close to the Stettiner Bahnhof, where they had arrived from Kolberg that Luzer produced a bombshell suggestion.

“Listen, Selma Liebling, I’ve been thinking. Kolberg is all very well but I’ll never get much further in the shoe business. It’s not what I want to do all my life. Why don’t we move here to Berlin?”

Selma was disturbed by the announcement. “But what on earth will we do here. It’s a big city. We don’t know a soul. Anyway, I can’t just up and leave my mother and family back there in Kolberg. What can you be thinking of?”

“Of course you can’t my darling. Of course you can’t. I don’t expect you to. First I shall take a closer look at what openings there are for me to start a small business here. It doesn’t have to be anything spectacular. I couldn’t afford anything too risky...Why don’t we at least try?”

And try he did. With the help of mother-in-law Berta, he rented a small ground floor apartment in the Invalidenstrasse, a busy street off the Friedrichstrasse in North Berlin, bought himself a long trestle table and filled it with small articles of haberdashery, zips, buttons, multi-coloured ribbons, handkerchiefs, as well as ladies’ underwear, men’s socks and ties. He insisted on stocking that table only with the best quality goods and selling them at low prices. The year was 1926.

Every morning he would get up at six and by seven o’clock had his table of wares open just inside the big double doors that led to the courtyard of No. 33 Invalidenstrasse. The crowds hurrying along the street to their places of work or to the nearby Stettiner Station would first glance at the available wares as they passed by, then stop and look more closely. By the end of the first month, the “stall” was a going concern and starting to make a profit.

In the winter of 1930 Selma became pregnant and on November 8 that year I came into the world, opening my eyes in the labour ward of the Berlin Jewish Hospital. Looking back at those early photographs, I can only describe myself as thoroughly ugly. How could such an abominable baby have been born to such an attractive couple? I looked Japanese, with little slit eyes, and my complexion was more brown than pink. I was, my parents later told me, jaundiced. But I was loved. And thoroughly spoiled.

Among the earliest memories I treasure, is waking up in the half light and watching my father tugging big boxes as quietly as possible towards the front door of our apartment, then still on the central courtyard of the house, and from there dragging them to the big double doors that opened to the busy street with its noisy trams, cars and horse-drawn carts.

My mother would also be up, busy brewing the coffee and cutting slices from a big brown loaf. For me there was milk and more milk as well as some porridge oats. When I was big enough to walk, I would skip around the courtyard and watch as my parents sold the wares from their stall.

At weekends, Grandma Berta and my uncles and aunt would come to visit. By now they had all moved to Berlin and some of them had married. Isi, the eldest, had created a veritable stir by bringing Mary to the house and introducing her as his fiancée. Mary was not only ravishingly beautiful but she was also a Roman Catholic. To marry “out” was regarded with distaste bordering on repulsion and fear. But Isi was adamant and Mary was reluctantly accepted into the family. Their daughter, Liane, was born on December 18, 1930. She was just one month younger than me and was to become a close and lifelong friend.

My parents (pictured) could not enter theatres or cinemas unless they were Jewish theatres or cinemas. They joined the one remaining Berlin Jewish Cultural Association, of which this is their membership card.

Heti, too, found the love of her life and married a young electrician called Benno Itzig. Their son, Heini, who was a year older than me and Liane, also became a close friend to both of us. But, alas, I am unable to add “lifelong”. Heini, along with his mother and father, as well as my darling Oma (grandma) and all her children, except my mother, met their deaths in the Nazi extermination camps of Theresienstadt, Bergen Belsen and Auschwitz.

But I go too fast. My childhood – at least, the first five years of it – was a happy one. My father’s haberdashery stall became so successful that he rented a small shop just along the road at No. 31. It stood opposite the Nordland Hotel, which was always packed with tourists from Scandinavia, and next to the area’s busy main post office. My mother was put in charge of the shop and was even given an assistant, while Dad continued to work the stall. But by 1933, both businesses had grown so much that the stall was abandoned and my father joined my mother, whom he would always address as “Fräulein” in front of customers. “It makes a good impression and shows that the business has several assistants,” he would explain.

That same year, Germany’s unemployment had reached critical proportions. A man named Adolf Hitler was making trouble. People took little notice. He had, after all, been trying to muscle in on politics for some years and had never been successful. Only a year after Germany’s defeat in the Great War he had joined a small, inconsequential party which he renamed the National Socialist German Workers’ Party and in 1923 he tried, again unsuccessfully, to overthrow the Bavarian government and ended up in prison.

There, this young and ambitious man, who was born Schicklgrüber in Upper Austria and could not rise beyond the rank of corporal in a Bavarian regiment, wrote a book called Mein Kampf (My Struggle). He didn’t actually write it as he was not a very talented writer, but dictated it to one of his closest friends, Rudolf Hess.

The book became his political will and testament and, after his release from jail, he continued to tour the country, speaking on street corners and promising those who would care to listen, full employment, food in their bellies and a world without Jews.

He failed to beat Germany’s President, General Paul von Hindenburg, in the 1932 elections, but to everyone’s surprise and to the shock of the country’s Jewish population, he was elected Chancellor shortly after Hindenburg’s death in August, 1934. It was a cue for total mayhem. He ordered a suspension of the German constitution, made capital from the burning down of the Reichstag building and brought the NSDAP (the Nazi party) to power. Any opponents he might still have had within the party were murdered on his orders by his personal bodyguards – the SS – in what became widely known as the Night of the Long Knives.

For Jews it was the beginning of the end. My father decided to change his name – but only unofficially. To family and friends he became known, not as Luzer, but as Hans. It was “more German”, less foreign. My own name, Horst, was of course as German as Leberwurst. I later came to hate it as I always associated it with the Horst Wessel Lied – the Nazi marching chorus that was sung with gusto at every rally and was always accompanied with arms outstretched in the Heil Hitler salute. It had become even more popular than Germany’s own jingoistic national anthem: Deutschland, Deutschland Über Alles.

By the time I was four, we had moved out of our ground floor flat at the other end of the courtyard to a larger, more comfortable one on the first floor, with a balcony that overlooked the Invalidenstrasse. From there, I recall seeing uniformed guards in front of my parents’ shop. A placard was pasted on their window: Deutsche Wehrt Euch: Kauft nicht bei Juden!, it commanded (Germans Defend Yourselves: Don’t buy from Jews). Danish and Swedish tourists from the Nordland Hotel took no notice and continued to enter the shop to buy things they didn’t even need. “I cannot understand what or why this is happening, Herr Izbicki,” one Swede told my father. “All I know is that it’s wrong and cannot continue like this for long.”

But continue it did. As early as 1934, Jews were forbidden to possess health insurance. They were also barred from qualifying for legal professions. A little later, they were unable to serve in Germany’s armed services and, if they were artists, actors or comedians, they could not join any “Aryan” association but were confined to a “Jews only” cultural union.

A few years later, on August 17, 1938, we were presented with yet another name. An order went out: all Jewish men had to add “Israel” and all women “Sarah” to their names on legal documents, including passports. My mother’s name on her identity card became Selma Sarah Izbicki, while my father’s was Luzer Israel Izbicki and mine, the card of a little child, stated: Horst Israel Izbicki.

Shortly after Hitler’s election as “Führer” a special brigade of Hitler Youths was founded. Schoolchildren were given well pressed khaki uniforms with swastika armbands and made to join these regiments. They were proud to serve the Führer, and march round the streets of Berlin carrying pots of white paint and brushes. On my parents’ shop window and on the windows of hundreds of other Jewish shops and department stores throughout Germany, a huge letter “J” was painted. It stood for Jude and acted as a “stop” sign to any would-be customer.

My parents were aghast. They would sit for hours in the evenings speaking in whispers, wondering what the future held for them. All their hard work was being drained away by the actions of the new Nazi government. Like so many Jews in Nazi Germany, my father felt that it could not go on much longer. Reason would prevail. But the years passed and the persecution continued. By 1935, Jews started to disappear. News got round that they had been arrested in the middle of the night and dragged away to prison. Why?

“There must be some mistake,” my father said one evening as he heard of yet another friend’s arrest. “Perhaps they didn’t pay their tax properly. Or maybe they were caught listening to a foreign radio station” (listening to anything other than the German radio had been strictly forbidden).

People started talking of hearing loud banging on the doors of apartments occupied by Jewish neighbours and seeing men being dragged down the stairs and packed into Gestapo vans. The Gestapo – short for Geheime Staatspolizei(secret police) – in their black uniforms, highly polished leather boots and caps whose leather bands were surmounted by a silver skull and crossbones, became the most feared of all Nazi officials.

No one knew for certain the destination of those who disappeared in the middle of the night. Prison was all one heard to begin with. Then there were rumours that those arrested had ended up in a camp. I think I was five when I first heard the word Konzentratsionslager (concentration camp), later abbreviated to the more simple yet ominous KZ. One uncle had been taken to a place called Dachau He was never seen again.

As a child, I can recall my parents speaking in low voices after the evening meal. But I did not share their fear. Far from it. Like most children, I found the smart uniforms of the Nazis, whether it was the brown of the Hitler Youths or the black of the Gestapo, exciting and when I saw them marching down the street, I would stand and wave and even give the Heil Hitler salute. When it was returned, I felt proud.

“Why can’t I join the Hitler Youths?” I asked my mother when I was about seven. “You’re too young, Horstchen,” she would reply. “So when will I be old enough to join them, Mutti?” I insisted. “I don’t know my Liebling, we’ll have to see...later...later maybe.”

But later never came and I grew up in a Berlin full of bunting and music. Swastika flags flew from thousands of windows and I could not understand why our windows stayed flagless. Martial music blared from loudspeakers attached to lamp posts lining the streets along which people strode giving each other the Nazi salute with a barked accompaniment of Heil Hitler!

There was a cinema in our street and I would stand outside its doors admiring the still photographs of scenes from the film being shown. But I could not enter the cinema to see the film. Jews were not allowed to enter any place of entertainment other than a Jewish theatre. I simply failed to understand why – not even after I had learned to read and could see for myself. The notices outside the cinemas were very clear: Juden Verboten (Jews Forbidden).

I learned to read and write at a Jewish school which I attended from the age of six. Our teachers were, of course, all Jewish. From January 1937, they were no longer allowed to teach non-Jewish, German children, but were confined to Jewish educational establishments. That same month, Jews could no longer practise accountancy or dentistry (“A Jew’s hand inside an Aryan mouth is unthinkable!” the Nazi “house journal” Der Stürmer declared).

I enjoyed school and loved my teachers. They coached me with affection and patience and made sure that I could do joined-up writing almost from the very beginning. German teaching was by rote but it was drummed in not by threat of punishment or, worse, the cane, as in so many English schools, but by gentle persuasion. By the time I was seven, I could read and write reasonably well.

In the summer of 1937 the school took the children on a week’s holiday to the seaside. My father gave me five marks to spend during the week and on the train, children lined up to hand their pocket money to a teacher who noted down the amounts against the children’s names in the register. When it came to my turn, I searched through all my pockets but the five mark coin had gone. I was distraught The teacher was sympathetic but could do nothing other than to note a “Nil” against my name.

At the seaside, whenever the children were asked: “Who wants an ice cream?” I shot up my hand amongst the others. But I couldn’t have an ice cream as there was no money to pay for it. For days I was miserable. But it was no use crying about it. Class friends let me have a lick of their cornets and wafers and others handed me the odd sweet. Then, on the Saturday, there was a surprise. My father came to visit. He had bought a large bag of peaches and we went for a walk along the promenade and sat down on a bench to eat them. The juice dribbled down our chins and we both dissolved into spasms of laughter. It was a glorious afternoon and, to this day, remains among my happiest childhood memories. The fact that he also gave the teacher some pocket money for me was an added bonus.

The author as a young man of two years in Berlin.

Hold the Front Page: The author in Berlin in 1932 – before the troubles started.

I treasure one other happy memory – also from that same holiday. We had spent part of the afternoon splashing about in the sea and were then called back to the beach and told to lie down on our towels and rest. I found myself lying close to a little girl about the same age as myself but from another class. She had long black hair that flowed across her shoulders and down to her waist. I found myself wanting to touch it. I reached out my hand and gently stroked her hair. It was, oh so silky. There was no reaction, either positive or negative, from her. My eyes closed and I fell fast asleep. When I awoke, I was alone on the beach. The children were all up – and queuing for their ices. I have had a thing about long hair ever since.

Back in Berlin, such happy memories are replaced by those of a more gloomy nature. The post office adjoining my parents’ shop had a long hall leading to the entrance. Showcases containing a large variety of goods, including sparkling jewellery, leather goods and toys, lined each side. There was also one large window in which stills for films showing at the cinema across the road flicked on a rotary arm, so that a picture would hold the onlooker’s attention for several seconds before being replaced by the next one. This and the toys could sometimes occupy me for many minutes on end.

One day as I was watching the picture show for the third or fourth time round, I felt a man’s face close to mine. With a start, I turned and saw this gnarled, ugly, pock-marked, hairy face with piercing eyes. I could smell the man’s stale breath and felt his hand clasp my wrist in a grip of steel. I could not move and was terrified. “Listen little boy,” the man rasped, spittle spraying my face. “I am going to go into that post office and I want you to wait for me here. You understand? You’re not to move from this spot. And when I get back,” he looked round furtively to make sure no one else was listening, “and when I get back I shall cut your throat from here (the thumb of his free hand touched my ear) to here (and it crossed along the throat to the other ear). Understand?”

The tears of fear welled up and I nodded my head. He let go of my wrist and produced a knife from the pocket of his long, smelly greatcoat. He waved the knife in front of my face and turned to stride to the post office. I was rooted to the spot. What was I to do? He had ordered me to stay there. But to have my throat cut on his return? I looked to the post office doors. There was no sign of him. I turned and looked towards the end of the hall and the exit. If I made a run for it, would he catch me? I had to take a chance and ran as fast as my legs would carry me, into the street, turned right and sprinted, panting and screaming into my parents’ shop.

Customers were shocked to see this little boy in such genuine anguish. My mother rushed to me and escorted me to the store room at the back of the shop. “There’s...there’s a man,” I blurted out between sobs, “who’s going to cut my throat!” “What man? Where? Horstchen, there’s no one and no one is going to cut even a single hair from your head,” my mother said, hugging me and trying to calm me down. But she was perturbed. There were madmen lurking in Berlin who might well murder children. And it wasn’t even anything to do with being Jewish or non-Jewish.

My father telephoned the police and then left the shop to make a search for the man with the long overcoat and pock-marked face. But he had clearly got away. The police said they had made a search. Maybe they had, but even the police, who should not be confused with the Gestapo, did not burn any midnight oil to assist Jews.

On another occasion, I had taken myself off to a pretty little park a few hundred metres south of the house in the Invalidenstrasse. It was a crisp autumn afternoon and the gold-red leaves had created a colourful carpet across the paths that criss-crossed the park from one end to the other. There was a sandpit for children and I loved to build my castles and bake sand pies. Somehow, although I was often alone there, I was never lonely.

On this occasion, I had hardly been there for more than ten minutes when I was joined by a group of eight boys and two girls One of the boys, a lad of about my age, seven or possibly eight, addressed me: “We’re playing cowboys and Indians. D’you want to join us?” I was thrilled and readily accepted the offer. We split into two teams, but I seemed to be the only one chosen to be an Indian.

“Tell you what,” the leader said, “you’ll be the Red Indian we’ve just captured. So we’re going to tie you to a tree. Later, we’ll all be Red Indians and we’ll come and rescue you.”

It sounded all right to me. I didn’t mind a bit when they produced a roll of strong string and bound me, hands, feet and neck to one of the slimmer trees within the thicker undergrowth of the park. “We’ll be back soon,” they cried as they rode away on their imaginary horses, leaving me to await my rescue. Minutes slipped away and turned into what seemed like hours. I became worried – and started to shiver from the cold. What little light there had been was now rapidly fading. I could hear a handbell being rung – the signal for the park’s closure – and I started to call for help. “Help! Help me! Oh, help me, please...pleeeease!” But no one heard. No one came. I was now completely alone and very, very scared. Darkness enveloped the wood and I could hear the scrabble of animals as they came to explore their territory. I had visions of wild beasts, tigers, lions and bears coming to tear me to pieces. I could feel huge imaginary rats gnawing away at my legs. I screamed and screamed.

I was not heard and was left untouched and alone. I was unable to move. The knots the boys had tied were extremely tight and seemed to get even tighter the more I wriggled. At last, cold and weary from crying, I fell fast asleep, only to be further tortured by nightmares in which I was running away from a cluster of devils, whose cloven hooves were rapidly advancing on me, their fangs ever-closer to my face. I awoke several times, each time in an ice-cold sweat.

Meanwhile, my parents, frantic with worry, had contacted the police and a search party was organised. But where could they look? My friends had all been contacted, all safe and sound having their supper at home with their mothers and fathers. My favourite haunts, such as the rear of the post office, where I used to go and “direct traffic”, beckoning the postal delivery vans as they rushed from their parking lots, and the station which, though out of bounds as a prospective place of danger to little children, still managed to lure me to its platforms to watch the steam trains coming and going. The park was totally ignored. Its gates were firmly shut and its fence too high for a little boy to climb.

It was about eight o’clock in the morning, shortly after the park had reopened, that one of the two girls arrived at my side. She produced a pair of scissors and proceeded to cut away the string that had kept me so firmly bound. “There. Now run home. You must not tell anyone that I came to free you. D’you understand? No one must know. You’ve got to promise,” she said over and over. I was so relieved, so very happy to be alive and at liberty that I would have promised her anything. As it was, all I could do, my teeth chattering from the bitter cold, was to blurt out: “Thank you...oh, thank you so very, very much!” I ran all the way home and into the arms of my parents. Neither of them had slept that night and they were as weary and haggard as I – and, for the first time since the launch of the shop, it opened late.

Bad memories always last longer than the good ones but my childhood was by no means an unhappy one. Far from it. Oma, my lovely grandmother, came to live with us at No.33 Invalidenstrasse in 1936, and looked after me as only a Jewish grandmother can. While my own Mutti and Papa were busy working in the shop, she would sit me on her lap and tell me the most beautiful stories. She and my mother were gifted story tellers, weaving wonderful yarns about little boys and their adventures on mountains and the high seas. Their love of language must have rubbed off on me and might even have sparked off my own attraction to spoken and written words.

Oma also owned a pretty little yellow canary to whom she would speak for long periods of the day. “He understands every single word, you know Horstchen,” she would say earnestly. And I believed her, for the bird would hop from rod to rod inside his cage and look Oma in the eye and chirp as he passed. “You see, Horstchen. He’s answering me.” “What did he say, Oma?” “He said that he is very happy to be chatting with me but please could I give him some more of those lovely seeds to eat.” And she would go and fetch his seeds and pour some into his feeding bowl.

During the day, we would put the cage out on the balcony that looked down on the Invalidenstrasse “Let him see all the people and the trams. He’ll enjoy that,” Oma used to say. That summer was exceedingly hot. Oma had taken a trip to see friends in the country outside Berlin; my parents were in the shop; I was at school; and the canary was on the balcony. He had tried desperately to keep cool and had gone into his birdbath. But the water was practically boiling and, when I came back home from school, the poor little thing lay dead, its feet pointing up to heaven. I dissolved in tears and ran to the shop with the news.

What would Oma say? Her best friend, dead? And through our negligence! My father immediately took charge. He ran back to the apartment, took the cage into the room and the bird out and sprinted to the nearest pet shop. He put the canary on the counter. “Please have you got a canary exactly like this one? We must have it immediately.” The pet shop owner understood the problem at once and produced two or three canaries. One of them was an almost perfect match. He was transported back to the house and into the cage to await Oma’s return.

She strode to the cage and started her conversation. “There now, there, did you miss me?” she said soothingly. “I’ve brought you some nice little seeds. Here...” and she poured a few into the pot. The canary stared but did not chirp and did not fly from perch to perch. Oma could not understand it. “What is the matter with you today? Not speaking to me? If I didn’t know any better, I’d think you were a stranger.” Papa chipped in: “It was rather hot today, Berta, and the poor thing was outside too long and has probably caught a bit of sunstroke.” This was accepted but Oma and the canary never seemed to renew their old close relationship.

My cousins Liane and Heinz often came to visit and stay over weekends and we would play for hours with my toys and board games. I did not get many toys, but once a year on my birthday, I would always be given one “super present” and lots of smaller ones from friends and family. So one year, I awoke on the 8th November, to be called into the dining room where the table was laden with my favourite foods for breakfast and a big birthday cake (to be eaten later when my friends would come for the party) and at one end of the room stood a beautiful Punch and Judy theatre. I stood and stared in wonder when two puppets would poke their wooden heads over the edge of the stage and wish me a happy birthday. It was my father who stood behind the theatre and manipulated the glove puppets. A great present that provided me with hour upon hour of make-believe and provided a foretaste of my lasting love for the theatre.

On another birthday, there was a pedal car which I would ride around the courtyard and in the park (under Oma’s supervision!); and on another, there was an indoor swing with all the trimmings – rings, bars, ropes. It was fixed to the opening between the dining room and the lounge for me to perform my acrobatics.

My eighth birthday on the 8th November 1938 was comparatively disappointing. I was presented with a watch. I had always wanted a watch but, when it was given to me, I felt that it was somehow too utilitarian. I couldn’t play with it. On this occasion the table was not laden with goodies, but just a few little cakes. It was all a bit down-key, almost solemn. My parents were apologetic. “This year, Horstchen, we cannot give you as good a present as we should have liked. Things are not looking very good. But we will make it up to you. Believe me,” Papa said and gave me a hug. Mutti kissed me and I noticed that there were tears in her eyes. “Na, mein braver Junge, mein Liebling” (My brave boy, my darling) she whispered.

The next day would make me understand what they had meant.

They had kept one or two things from me. They had not told me, for instance, that in April of that year, they, along with all other Jews in Germany, had to register what wealth and property they owned. This did not just mean money and bank balances, but any valuable paintings or books or heirlooms. My father was an ardent coin collector and possessed coins from the ancient Roman era as well as from Victorian England; he had also bought some exquisite paintings, not by the Masters but by reputable painters whose names would one day become famous. These items had all to be registered. The Nazis needed to know what loot they could expect. The following month, Jews had to register their businesses. On July 15, Jewish doctors were barred from practising medicine and on August 11, the big synagogue at Nüremberg was destroyed by fire.

For Germany’s Jews, life was becoming decidedly sickening.

November 9th started with a persistent ring of the doorbell. It was just after seven o’clock in the morning. Mutti went to open the door and let one of our neighbours in. Herr Schultz was a neat little man with a thick moustache and was a known member of the Nazi party, wearing the little swastika insignia in his lapel. But, for all his political gesturings, he had remained decent and friendly towards my parents and would often run his hand through my hair affectionately when we met in the street and say: “Na, how’s Horst? Be good. You’ve got good parents.”

This time, I could hear him tell my parents in almost a whisper: “I’ve just heard. Your shop will be done tonight, around seven. I’m so very sorry. You’ve not heard it from me. You’ve not even seen me.” “Please wouldn’t you like a coffee, Herr Schultz?” my mother asked. “No. No thank you, Frau Izbicki. I must go. I really am sorry.” And with that he slipped out of the door and away.

My parents sat at the table with Oma, discussing their next move. “We must open the shop as usual,” my father decided. “Otherwise it would look suspicious. We must act as though nothing is going to happen. But then, this afternoon, we shall start taking all stock to the back room (the store room) and finally, we shall take every article out of the window and the showcase and bring everything to the back. That way, there’ll be no damage to the stock.”

I had no idea what was going to happen. I could not even have imagined it. But a few minutes later, I was to realise what horror awaited us. I ran to the window when I heard a kind of choral sloganising: Juden Raus! Juden Raus! Juden Raus! (“Jews Out”) was chanted over and over by a group of about thirty Hitler Youths armed with batons and bricks. Immediately across the road from our house was a leatherware shop called Stiller.

Their shopwindow was painted with a big white “J”, because the owner was a Jew. The gang stopped in front of the shop and started to smash the window. Glass sprayed into the road. They then ransacked the leather goods still on show in the window and continued on their way, still chanting their dreadful slogan. Policemen stood a few yards away at the corner of Invalidenstrasse and Chausseestrasse. They were watching but did nothing. One of them smiled.

I looked at the broken window and trembled. Is that what was going to happen at seven tonight? Just then, an old woman, almost doubled with arthritis, hobbled along the pavement outside Stiller’s shop. She went close to the window and started screaming: “Serves you right, you Jewish swine. You should all be dead. All be dead, d’you hear? Heil Hitler!” Her scream had reached a crescendo. Its pitch made one big jagged sliver of glass quiver in its putty casing. And, as she threw in an additional “Heil Hit!” and began to move on, the glass dropped, cutting through her skull. Her salutation to the Führer stuck in her throat as she collapsed in a rapidly growing pool of blood.

I vomited. And when I had finished vomiting, I believed in God.

I did not go to school that day. Or the next. Indeed, I have no recall of having gone back to school ever again in Germany.

My parents did as they had planned. The shop was opened and some customers even came to buy. Then, in the afternoon, they started moving goods from the many shelves, cabinets and glass show counter to the store room at the back of the shop. The clock was moving fast towards the appointed hour. At about 6.30 p.m. they began to clear the window. This is a slow process, as many articles were decoratively arranged and pinned down. I had put on a pullover and a coat, for it was cold and I wanted to see what was happening from the balcony. I was scared for my parents who were alone in the shop.

Somehow, word must have got round, for the street – a busy, bustling main road – was rapidly filling with people. A large crowd had gathered. The traffic had been brought to a standstill and there was an eerie silence. People stood and stared. And waited. My parents were popular, as was the shop. They had always been friendly and helpful to their customers and their neighbouring shopkeepers. The people were making their sympathy felt – but could do nothing to prevent what was about to happen.

At 6.55p.m. a large group of Hitler Youths, accompanied by squads of SA troops, marched their way from the Stettiner Station, past the post office, to the shop and started chanting their mantra: Juden Raus! Juden Raus! At the same time, they flung their bricks at the shop’s window. The bricks bounced back. There was laughter from the crowd and some people applauded. The Nazi hooligans grew angry and attacked the glass with their thick batons. Nothing even cracked. More applause and laughter. They had not reckoned on the thickness of the curved glass of that window.

Three of the leaders broke away and marched into the butcher’s shop two doors away. “Give us your heavy weights,” they demanded of the butcher, a burly bearded man of 45 with heavily tattooed arms. “What the hell for?” he wanted to know. “What d’you think? We want to smash that Yid’s windows next door!” “Then you can fuck off. You’re not getting my weights. Leave the poor bugger alone!” For his pains, the butcher had his head bashed by one of the batons and his glass counter smashed. And as he lay cut on his sawdust floor, the Hitler Youths dragged away his 10 kilo weights and returned to the task in hand.

This time the window gave way with a roar of splintering glass. There was a loud groan from the crowd and several whistles (German equivalent of booing). I saw some women openly weeping in that otherwise silent street and I wept with them. But my tears turned to screams when I saw the Nazi thugs picking up large splinters of glass and hurling them into the shop. I knew my parents were inside and that these deadly missiles were meant for them. They could be killed. I screamed and screamed. Oma rushed me inside and hugged me to her. “Horstchen, Horstchen, it will be all right. You’ll see. Hush, hush, now” and she cradled me in her arms and rocked me like a baby. But I could feel that she, too, was frightened.

When I awoke, Mutti and Papa were standing, stroking my hot brow and rubbing my arms. They were alive and unharmed. Unharmed, that is, physically. Mentally, however, the damage would last them a lifetime.

That same day, some 7,500 Jewish businesses throughout Germany had their windows smashed and their stocks looted. The SA murdered around 100 Jews who had tried to defend themselves against the onslaught. Another 30,000 Jewish males were arrested and transported to the concentration camps of Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen. And, as if all this was not enough, hundreds of synagogues were set on fire, their holy scrolls burned or torn into shreds, their Torahs vandalised and cemeteries desecrated.

Among the synagogues to be attacked was the one my parents and I used to attend in the nearby Oranienburgerstrasse. It was a beautiful building topped by a large golden dome. Inside, I would join Mutti and Oma upstairs where all the women had to sit, but would also slip downstairs to join Papa among the men. Although one mad Nazi arsonist set fire to the Oranienburger Tempel as it was called, a courageous policeman recognised this mindless vandalism and rushed to put out the flames. He called the fire brigade and ordered the rest of the fire to be extinguished. His bravery has never been properly recognised.

Many years later, when the synagogue was rebuilt and reopened as a museum, I attended its launch. In the entrance hall stood a large glass-covered photograph of men at prayer in the old Tempel. I produced my camera to photograph the picture when to my amazement I saw a ghost. There in the third row of the worshipers stood my father. It was, to say the least, an emotional moment.

But back to November 1938. The Nazis, not satisfied with their vandalism, plunder and murder, blamed the entire episode on the Jews themselves and demanded payment for the damage caused. They cashed in one billion Reichsmarks (about £200 million in 1938 money) from Jewish pockets. To this day I still possess the receipt my father was given for paying 2,000 Reichsmarks Judenbusse (literally, a fine for being a Jew).

My screaming had damaged my vocal chords and I was unable to speak for many days. My father took me to the Jewish hospital, where they looked into my throat and found the chords covered in papiloma, knots formed from overstraining the voice. They decided to operate. But most of the experienced doctors had already left the country. They had been barred from practising medicine anywhere other than at the few Jewish clinics and hospitals that were dotted about the country. The ones that were left were not exactly quality surgeons. Instead of curing my condition, they made it worse.

My father was advised to take me to Professor Dr Carl von Eicken, Berlin’s eminent ear, nose and throat specialist. It was a risk. But the professor saw us and even called in a number of his students to see my throat. He carefully picked out several of the papilomae. “This is most interesting. Most interesting. How long will you be here, Herr Izbicki?” My father replied that we were shortly going to emigrate to Palestine. “Good. Good. I’ll give you the name of a colleague over there, in Tel Aviv. He’s the man for this. He’ll be able to help your boy.” And he wrote down the Jewish doctor’s name and address. “You realise that the only other person who has suffered from this vocal chord condition was Adolf Hitler. He got it from over-shouting his speeches. And I, so help me, operated on him in 1935 and gave him back his voice.”

My father thanked him and took out his wallet. But the professor pushed it away. “No, my dear Sir. Please don’t pay me. You people have paid quite enough already.”

Thank God there were still many people like him in Germany. But there weren’t enough and it was time to be rational. Oma, for her own safety, was moved to a Jewish old age home where we visited her every weekend. Meanwhile, my father had already applied for visas from the United States and the United Kingdom as well as for an entry permit to Palestine. Although many German Jews still believed that “there must be some mistake, which will surely be put right soon...” many others decided to call it a day and get out while it was still possible to do so. One needed a great deal of patience.

Meanwhile, however, Papa went into hiding, spending days and nights in the ruins of burned out synagogues and returning home only to have a shower and change his clothes.

The reason? Almost every day the Gestapo would come to our apartment and ask to see him. And every time Mutti told them that they were unlucky, that he wasn’t in. “You’ve just missed him. He was here until a few minutes ago but has had to go out on business. I’m not sure what time he’ll be back.” That would normally be that.

There was a day when a neighbour, Dr Löwenstein, paid us a visit. Like Papa, he was also in hiding and had come home for a change of shirt. He joined Mutti for a cup of ersatz coffee and an exchange of news. He was a widower and no longer saw many people. He wasn’t allowed to treat patients any more, so felt lonely and depressed. While he was in the apartment, the doorbell rang followed by insistent knocking. It meant only one thing – the Gestapo. Mutti took immediate control. She ordered Dr Löwenstein to get under a small coffee table and threw a large cloth over it, hiding the man below. “Horst, sit on the table, hurry,” she commanded and cleared the coffee cups, taking them rapidly to the kitchen on the way to opening the front door.

“Frau Izbicki, Heil Hitler,” the officer said. “Good morning, Herr Officer,” responded my mother calmly. “Herr Izbicki? Is he in this time?” “I’m so sorry, you’re out of luck again. He has just left.” “Well,” said the Gestapo officer with a slight smile, “you won’t mind if I come and take a quick look?” And he stepped past her and marched into the lounge where I was sitting, legs crossed, on the coffee table. As he approached, I got up. It was, after all, the proper thing to do. “So, my boy,” the officer said, taking my chin in his hand and squeezing it. “Is your Papi in?” “No, Sir, he’s not here. He has left on business,” I replied, feeling myself blush with embarrassment and pain for his fingers were hurting me. Beneath the table, a fully grown man in his fifties, was cowering like a dog, not even daring to breathe or scratch the itch that was troubling his nose.

The Gestapo seemed satisfied and, after a glance into the dining room and kitchen, he turned to the door and, with another “Heil Hitler”, marched out.

Dr Löwenstein crawled out from under the table, the sweat pouring from his face and tears from his eyes. “Thank you, Horst. You’re a good boy.” And he slipped me five marks. I shrank away. “No, no, really Herr Doctor, that is not necessary,” I exclaimed with all the authority of an eight-year-old. My mother backed me. “No, Dr Löwenstein. Horstchen is right. There cannot be any payment for an act of humanity. Wait a few more minutes, then go in peace. May the good Lord preserve us all.”

Two days after that incident, there was another that I shall never forget. Whenever Papa came home, I would have to stand on the balcony and keep a watch for the arrival of the Gestapo. This had actually happened a couple of times and Papa would then leave the apartment and climb the stairs to an upper floor and wait until the coast was clear. On this occasion, I had fallen down on my duty. I had watched from the balcony but then, as my father was ready to leave, I ran in to kiss him goodbye and be hugged by him.

This little ritual had obviously taken longer than usual for when Papa left and was proceeding down the stairs, he came face to face with the Gestapo officer. Both stopped and stared at each other. “Heil Hitler, Herr Izbicki,” the officer mouthed, then added: “What the hell are you doing here?” My father stammered his reply: “I – I was just leaving. I – I must make a number of – of visits...business visits, Herr Officer.” The Gestapo officer looked at Papa, then looked up and down the stairs to see whether anyone else might be within hearing. “I’ve not seen you. Now fuck off. And for God’s sake, get out of the country while you still can!”

My father stuttered his thanks and ran the rest of the way down the stairs and out of the house, while the Gestapo officer continued up to our apartment, rang the bell and knocked his threatening knock, to be told by Mutti: “You’ve just missed him...”

Even the Gestapo possessed the odd human being.

While my father continued the cat-and-mouse game, hiding himself under the ruins of synagogues, my mother was left to take care of me and look after what little remained of the business. The Chamber of Commerce was now sending “interested parties” to look at the shop and make “offers”. Several such offers were received and these would be discussed by my parents, when Papa was home for those short periods. There were also times when he would go to the old age home to see Oma and Mutti and I would meet him there.

The so-called offers were, of course ludicrously low, but one of them, the best of a bad lot, had to be accepted before December 3. From that day, all Jewish businesses became “Aryanised”, taken over by full-blooded Germans, many of them Nazi party members. What little we received for the shop and all its stock was further taxed. The result was not even worth banking, but at least we were all alive and still at liberty. Hermann Göring was put in charge of “The Jewish Question” and made sure that his own pockets would be lined with Jewish savings and treasures.

Around February, 1939, all items made of silver or gold had to be surrendered to Göring’s Ministry. Anyone who was caught hiding some treasured piece of jewellery was immediately arrested and sent to a camp. Wedding and signet rings were allowed to be kept. My father, even at that highly critical and dangerous time, decided to take a risk. His coin collection contained a number of English gold sovereigns and half sovereigns. These he took to a friendly jeweller who melted them all down and turned the resulting lump of gold into a large signet ring. It was heavy and the only article of value that came out of Germany with us. It was to be kept for “a rainy day”.

Even in England, where it rained a great deal, the ring was never sold. It is with me to this day and will be passed on to my son and, I hope, by him to his son in memory of a period that showed man’s inhumanity to man. A memorial to a period that should never be repeated.