Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

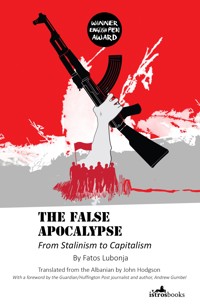

- Herausgeber: Istros Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The book contains eleven dramatic and often horrifying stories, each describing the life of a different prisoner in the camps and prisons of communist Albania. The prisoners adapt, endure, and generally survive, all in different ways. They may conform, rebel, construct alternative realities of the imagination, cultivate hope, cling to memories of lost love, or devisenincreasingly strange and surreal strategies of resistance. The characters inndifferent stories are linked to one another, and in their human relationships create a total picture of a secret and terrifying world. In the prisoners' back stories, the anecdotes they tell, and their political discussions, the book also reaches out beyond the walls and barbed wire to give the reader a panoramic picture of life in totalitarian Albania.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 319

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Fatos Lubonja

Like a Prisoner

Translated from the Albanian byJohn Hodgson

Prologue

The Caged Wolf

The sight of that repellent human whirlpool has remained my only clear memory of that first day. I’ve forgotten most of the prisoners with whom I travelled in the dark metal box of the prison van from Tirana. I’ve forgotten the name of the man whose wrist was locked to mine in a single pair of handcuffs for the journey. I’ve forgotten almost all our conversation along the way. I remember nothing of the search we were subjected to when we climbed out of the van and stepped on the inch-thick frozen snow. But the sight before me on that chill, frosty day in February 1975, when I looked down at the prisoners’ zone from the top of a flight of steps, has remained vivid in my mind as one of the most important encounters in life.

What I saw was the area I later learned that prisoners called the ‘field’, where I found myself staring at a strange mass of human creatures, of a kind that I had never seen in my life. I had seen larger crowds in queues, or at the gates of stadiums, but it was the way these people moved that made this swarm of humanity so unusual.

I gradually realised that what made this scene so outlandish was the way the prisoners anxiously paced to and fro, back and forth within that confined space. Whether they walked alone or in twos and threes, they all displayed the same nervous agitation, as if trying not to be sucked into a whirlpool, but unable to break free of its centripetal force. Alone in my cell, I had felt the neurotic frustration of a wolf in a cage. This was the same thing, at a collective level.

Only a few days before my arrest, I had seen on television a documentary film about the mental stress suffered by wild animals in European zoos. The most sensitive survived the journey from Africa only with great difficulty. Some like the giraffes died on the way, and others showed symptoms of different illnesses caused by their severe problems of adaptation.

I remembered the wolves best. The film showed a wolf in a cage at the zoo, endlessly pacing around in a narrow circle behind the bars, never looking outside. This animal, whose extraordinary energy enabled it to cover up to two hundred kilometres a day in the wild, was now reduced to blind, directionless circling. This endless round was a sign of neurosis. Then there were scenes of wolves in modern zoos, which had attempted to create conditions as close to nature as possible. Here the wolves felt they were merely in a larger cage, and still wandered round and round, but in a larger circle.

I would have forgotten this film, except that a few days later I was the caged wolf myself. When the guards threw me into the twilit cell for the first time and closed the door, I fell flat on my face. I lay on the floor for a few moments, or maybe hours, I have no way of telling. These were the most terrible moments of my life. Then I instinctively rose to my feet and started to pace my cell. The next morning, I started the same endless pacing once more, and again the day after. All day I crossed back and forth between the door and the opposite wall, just like the wolf in its cage.

Now, having been moved to the labour camp of Spaç, I was faced with a ‘modern zoo’ with more space, but still surrounded by barbed wire. That dreadful eddying crowd on the field was driven by the same neurosis as the wolves, and there was an entire pack of them. This seething humanity was given an even more remarkable appearance by the colour of the prisoners’ clothes. The prevailing hue was the grey of the outworn military greatcoats that were sent to the prison storehouses and dyed with varying drab shades. But beyond those different shades of grey, these disarmed soldiers without belts or weapons were rendered even more grotesque by their hats and caps. These caps were not part of the prison uniform, but made by the prisoners themselves. They came in assorted shapes, and even a single cap would have several colours. Most were knitted from multicoloured wool or sewn from all sorts of scraps. Some could scarcely be called caps, but were mere rags pieced together to shield the head from the cold, and barely covering one ear, creating an even more repulsive appearance.

This human swarm became even uglier when it suddenly stopped its movement the moment we appeared at the top of the steps. The prisoners paused in their pacing and stared up in wide-eyed excitement at the arrival of something to brighten their lives – I later learned that in prison slang the arrival of the prison van meant a delivery of ‘meat’, because some of the prisoners saw in the newly-arrived young men a chance to satisfy their sexual appetites.

I felt I was entering a madhouse.

The guard who was our escort ordered us to follow him straight to the showers. The camp storekeeper, an elderly prisoner, tall and wizened, gave us the prison uniform to replace our own clothes worn in our free life. This uniform consisted of two pairs of long underwear and a shirt of tough prickly cotton that tore the skin at first, a brown duck suit, padded trousers and jacket of a colourless brown to protect us from the cold winter of Spaç, moccasins made of car tyres, and an old military greatcoat, dyed grey.

Mirrors were not allowed in the camp, so when I was taken to a room and shown where I was to sleep, I satisfied my need to see how I looked in these clothes by going to the window. I saw myself in prison uniform for the first time with mixed feelings. On one hand, here was a figure so hideously dressed that I couldn’t believe it was myself, and at the same time, with freezing hands, I tried to adjust these new clothes so they would fit me as well as possible.

With this contradictory desire to adapt, and yet never to adapt, I descended the steps from the dormitory to launch myself at last into the swirling currents of my fellow-prisoners. As they welcomed me, their handshakes, the look in their eyes, their conversation, and their smiles made me realise that these creatures in their ugly caps, greatcoats and moccasins were human beings, very similar to myself and the people I had known outside. Yet I could never shake off that feeling prompted by my first sight of them, when the place had looked like a madhouse, and the sense that I had plunged into a whirlpool of people, united by the neurosis of the caged wolf, and into an existence that was a negation of everything I had lived for.

Eqerem

I

The rooftop was the largest open space in the camp. The prisoners assembled there twice a day for roll-calls and three times, at the start of each shift, to wait for the squad of duty guards that escorted us to the mine. Its surface, the size of two or three volleyball courts, was spread with concrete and enclosed by iron railings. The roof covered the baths, latrines, the store for our work-clothes, and the private kitchen. Below it stretched the perimeter fence, with its watchtowers, and then a slope that fell ever more steeply down to the stream. Opposite, above the stream, rose a range of high hills covered with scrub, climbing ever higher towards the towering peak of Munelle. This range of hills was the only landscape visible from the camp that was not ringed with wire and watchtowers. It was a tall, natural wall that blocked the horizon from the north-west to the northeast, and the prisoners gazed every day at its grim sameness and ponderous bulk. Only three isolated houses were visible on this hillside, very far apart, from which several shepherds’ tracks descended, appearing and disappearing through the scrub and bracken. These paths met below at the bridge over the stream, which lay as far as our eyes could see from the rooftop.

It was only during the morning wait on the rooftop that the monotony of the landscape was broken for a few moments, when a young girl who lived in one of the three houses would climb down the slope. Her descent, from the moment she appeared until she reached the bridge over the stream and vanished from sight, took some time.

People said she worked in the mine administration. Someone had given her the nickname ‘the Doe’, and that is what everybody called her. Occasionally, some women of Mirdita in their local costume would appear on the hillside opposite, but not even the prisoners’ ravenous sexual stare could penetrate their trousers, wrapped around with skirts. The Doe was the only woman ever to appear on that hillside dressed simply in trousers that emphasised her fine, round thighs, with muscles that swelled as she leaned her weight on the stony steps of the path.

The prisoners on the rooftop could see her as soon as she emerged from her house, which was a long way off. At first, she was a barely distinguishable smudge among the rocks and undergrowth. Her admirers knew precisely at what point she first appeared, and would follow her from there, while the less devoted watched her only after she came close, when nobody could resist her appeal. The boldest shouted after her, and others exchanged remarks or followed her with their eyes, lost for words. In the imagination of those shorn heads watching from behind the barbed wire, it was as if a vast nude figure of the Doe had spread over the entire hillside, flying rather than walking.

* * *

I noticed Eqerem a few days after I arrived at the camp, just after I had watched the Doe’s descent for the first time. She had crossed the bridge and disappeared from view, when a tall, slender prisoner whom some called Pandi and some ‘Pignose’ joined his two thumbs above and his two index fingers below to form the symbol of a vagina, and shouted, ‘Suzi, come on Suzi!’ The prisoners who were familiar with this game made a space, and a strange creature, different from the other prisoners, came out from the crowd. As soon as he saw this vagina in the air, he removed his cap and charged towards it with head forward, as if he were going to butt his way inside. Pandi backed off a little, not allowing him to touch it, and so began Eqerem’s dance. His feet and hands moved in a regular rhythm, but the main movement was of his extraordinary head, and became more aggressive and more ecstatic as it approached the ‘vagina’. Pandi fell back and twirled round. Eqerem followed him with a leap, and the circle of prisoners grew wider and wider, all laughing and enjoying themselves. This scene seemed to release the tension caused by the alluring appearance of the Doe.

Eqerem’s extraordinary head made his dance all the more grotesque. It led me to a discovery of a kind you can only make in prison, where heads were shorn to the scalp once a month. There are some scalps that wrap round the skull, covering it in irregular folds with deep wrinkles and furrows that a barber’s razor cannot penetrate. This means that the scalp, when shorn to zero, appears mottled with pale and black patches. Spaç had about five hundred prisoners at this time, and Eqerem’s was the only head of this kind. These furrows crossed the whole of his shaved head. They were shallower on his pate, and deeper at the back. Eqerem was short, with a crooked body. His face was pale and bloodless – only this kind of face, you could imagine, would fit that skull.

The prisoners said that those wrinkles were also connected to some inner disturbance, because Eqerem occasionally suffered from epileptic fits, even sometimes in the middle of his dance on the rooftop. At these times, he would start delivering a wild speech with a jumble of words that sounded like German, though only the word ‘Scheisse, Scheisse’ could be distinguished. This would last about ten minutes. He would shake and snort, his eyes bulging alarmingly, and then he would suddenly collapse on the ground, trembling, shuddering, and drooling at the mouth. He would faint, and the prisoners would carry him indoors, still unconscious.

The amateur quacks in the camp claimed that this was not epilepsy, but hysteria, and happened because Eqerem had never in his life had sex. He had been sentenced to fifteen years, having attempted to flee the country by swimming out to a foreign ship that lay at the harbour entrance. He was then about twenty-five. They said he had tried to escape because his obsession was to visit a brothel in the West.

* * *

In the daily life of the camp, Eqerem was very reserved by nature, and apart from his epileptic fits and his rooftop dance, his presence disturbed nobody. None of his family came to see him, and he was therefore ‘without support’. He kept a large bowl that he filled with a mush of bread and soup from the cauldron. He ate everything and never scrounged off anybody. He never argued with the guards, and they generally left him in peace.

Pandi was the only person to call to him in the name of Suzi. Everyone was astonished how he had managed to induce Eqerem to take part in such a game. If anybody else tried to call ‘Suzi’ to him or make the vagina sign, he would give them a furious look and make threatening gestures.

Eqerem had worked with Pandi for a long time in the same work gang, as a mallet-man. Tall ‘Pignose’ and another waggoner had the task of cleaning the mine-face from the debris thrown up by a blast, while Eqerem fixed the props and drilled holes in the rock. The work of the mallet-man was the hardest of all. The prisoners were scared of it, as if of a punishment, and many had refused it and even gone to the punishment cells instead. This was not because the mallet and auger together were very heavy, but because there was no wet-drilling in the mine of Spaç, and the making of the hole raised a terrible fog of dust, in which the mallet-man had to breathe for more than one hour, sometimes two, depending on the hardness of the rock. So it was usually tall and strong men who were chosen for the job of mallet-man. Eqerem was the only one, who, although short and feeble, took pleasure in this work. He insisted that if they did not give him a hammer, he would refuse even to lift a spade. When he set the mallet against his shoulder, he looked different. His entire body filled out and swelled with pride. He would turn his head to left and right so that people would see him. His white face shone and became flushed, and he was nicer to everybody. The prisoners immediately responded to this preening by teasing him, egging him on. They knew his secret pleasure. Pandi had discovered it, when one night he forgot to bring the clay which the dynamite-men used to stop the holes before the blasting, and had to take it to the face where Eqerem had begun his drilling. Usually, the waggoners kept their distance from the mallet-men as they made the holes, to avoid eating the dust: they cleared the rubble away from the face, prepared the clay, and waited below. When Pandi arrived, he noticed a curious thing amid the fog of dust raised by the mallet blows. As Eqerem drove the auger into the rock, he moved in a peculiar way. Pandi drew closer, and saw how he was swept away by the pleasure of this driving motion, almost in a state of ecstasy. Despite the dust in his mouth and the deafening noise of the mallet, Pandi waited to witness the scene until the end. As he hammered with his mallet, Eqerem shook, laughed, and exulted. When the auger was driven home, and had penetrated about ninety centimetres into the rock, which was the normal depth of the holes, Eqerem thrust the mallet into his crotch and, shuddering, achieved an orgasm accompanied by howls louder even than the deafening sound of the mallet blows.

People said that Pandi’s discovery of this secret turned him into Eqerem’s closest and most trusted friend.

* * *

When I arrived in Spaç in 1975, Eqerem had less than one year to go. As the day of his release approached, he began to brighten and open up. Pandi teased him more and more about the happy day that was approaching, goading him on to say what he would do once he was free. Eqerem would laugh and then take him to one side to tell him what he had in mind. His most ardent wish was to bury his head in Suzi’s vagina. According to Pandi, Suzi must have been a woman from Eqerem’s childhood, whom he had recalled only after finding himself in prison.

Prisoners’ hair was not cropped during the month before their release, so when Eqerem’s day of freedom arrived, his hair had grown almost to cover the furrows in his scalp, leaving a uniform surface. Strangely this made him no less ugly, but only different.

On the morning of his release, even Eqerem performed the usual ritual of handing round cigarettes. A wide circle of prisoners would gather round to say goodbye to the departing one. A close friend distributed cigarettes to these well-wishers, and it was Pandi who handed round the cigarettes for Eqerem who, for all his ugliness, looked positively handsome that day. His face glowed. Even the patches on his head had disappeared under the brim of the new cap he had put on.

Pandi teased him a little, advising him on the sort of behaviour to win Suzi’s heart. ‘And don’t tell her you were in prison!’ he repeated. He quickly made the vagina sign and Eqerem responded with a laugh, but a gentle one, without removing his cap or starting the dance. He seemed fully aware that after that day he would have to behave in a different way, and games of that sort would not be allowed.

Before morning roll-call, they called for him to be escorted through the gate, and he left, waving farewell to everyone.

II

Three or four years had passed after Eqerem’s release when news reached the camp that he’d been arrested for the second time. They said he had swum out to sea again, trying to reach a ship lying just out of the harbour. But he’d been caught halfway by the motorboats on patrol. Reportedly, he had been sentenced to another twenty years. Finally, the prison van brought him back to Spaç. On the day when we had seen him off, not many people imagined that he would find a woman and build a normal life, but nobody thought he would try to escape again.

His face was even paler. The wrinkles in his scalp were wizened, and his head was smaller, because he was thinner. He gave no explanation of his arrest. He was now even more taciturn. In the meantime, Pandi had been released, and the Doe must have married, because we hadn’t seen her for about two years.

Eqerem didn’t ask to go to work, and they left him ‘with 600 grams’, the bread ration of the brigade without employment. He filled his big bowl less often, and his appetite wasn’t what it had been. To buy odds and ends, he started sewing caps, a skill he had practised occasionally during his first sentence. He generally made white caps out of the linen footcloths that the camp issued to working prisoners. For these, he would ask for two or three packets of Partizan cigarettes. He began changing his own caps frequently, much more often than before, and he made them in a shape that hid as far as possible the back of his head where the furrows ran deepest. Some said that this frequent change of caps showed that Eqerem must have fallen in love with some young boy in the camp, but nobody could discover who it was.

Nor did he seem to suffer any longer from epileptic seizures. About a year passed, while he sewed caps and went unnoticed. But when spring came, his epileptic fits returned, reminding us of the old days. He would jump onto the third storey of bunks in the hut, and begin to rave, his eyes bulging. He would start his famous rant in German. Nobody knew why he used German for these speeches. Clearly, he wanted to assume a savage appearance, and perhaps it had something to do with the war films of his childhood, with their menacing SS men. There was always something tragic about these outbursts, and this stopped the prisoners from laughing at his meaningless jumble of German words. His fits always ended with the terrifying wail, ‘Scheisse, Scheisse, Scheisse.’ Then he would fall unconscious and foam at the mouth. Now that he had come to serve his second sentence, he shrieked his gibberish in an even more tragic tone. Prisoners who had recently arrived now heard the story about the Doe and the mallet and the fact that Eqerem had never slept with a woman.

* * *

In the year when Eqerem arrived, tension was building up in the camp, as happened when times got bad. People said that this was because the dictator was very ill, and close to death. Some of the guards enforced the regulations more strictly and seemed thrilled at this opportunity to show their sadism. These were guards who provoked and tormented prisoners most. They had all worked out ways of satisfying and entertaining themselves. The officers were more subtle. Two of them in particular, the timekeeper and the pay officer, liked to ‘have fun’ with roll-calls.

The first would leave the prisoners standing in lines for an hour on the rooftop in the sun or rain. It was the pointlessness of this that was intolerable. The second took pleasure in issuing orders for us to parade in front of him ‘at the double!’ making us perform about-turns at his whim, especially when he thought we were not quick enough. But tall Nue, a sergeant who accompanied the duty officers, had a different habit. As soon as he entered with the duty officer, before the counting started, he would give the order, ‘Caps off!’ These continual humiliations had to be endured, because any resistance would only become cause for regret.

But this bottled-up hatred ate into the soul. One day, Fetah did not remove his cap, and after roll-call was over, they slammed him into a punishment cell for a month and gave him a thorough beating.

At no time during the whole of his first sentence had Eqerem shown any spirit of rebellion towards the guards. But then one day the unit commander, as officer on duty, came to take the roll-call. He was a serious-minded officer, who never played sadistic tricks, but also never ordered them to be stopped. Alongside him there also came tall Nue, who at once gave the order, ‘Caps off!’

We could not tell how Eqerem detached himself at that moment from the assembled crowd of prisoners on the rooftop and stepped out in front of the commander. We supposed he was going to ask for something, when he began to wail in that terrifying voice we had only heard when he spoke German during his fits:

‘I am a ma-a-a-a-n! I am a ma-a-a-a-n! I am a ma-a-a-a-n!’

His piercing voice, his bulging eyes, and his appeal to the commander astounded us all. The commander paled a little and took a step backwards, but stood his ground. Two guards came forward, and shoved Eqerem back in line. We imagined that he would collapse and start foaming, but he did not. The roll-call began and was completed in due order. The commander hurried to leave. The squad accompanying him, led by Nue, did not forget to take Eqerem with them, and he followed them without a word.

Clearly, he would get a month in the punishment cell, but what sort of bashing he would get, nobody knew.

* * *

They brought Eqerem out of the cell before the month was up. He came out without a cap, but with several blue stripes running across the folds on his scalp, the marks of truncheons. He didn’t speak to anybody or complain. He stared without giving any reply to those who came up to him with questions. He didn’t line up even for bread, and, as soon as roll-call was over, would sit in a corner of the hut, totally withdrawn into himself. He even gave up wearing a cap.

This did not last more than a few days. One morning, as we assembled on the rooftop for roll-call, we learned that Eqerem had died during the night and they had taken him away for burial early in the morning.

Tall Nue did not come out to escort the duty officer that day, and nobody gave the order to remove caps.

Ferit the Cow, Our Partner

Not many in the camp knew Ferit’s real surname. We called him ‘the Cow’. To hear his real name used by one of the guards was always a surprise, as this Ferit Avdullai seemed a different person from Ferit the Cow.

* * *

Ferit was big-boned and fat, with a strange long-headed skull, protruding eyes and a broad jawbone. He even ate like a cow. At first sight, you would think this was the reason for his nickname, but in fact he was called ‘the Cow’ because of one of the stories, half-dream and half-reality, that Ferit kept inventing, and which passed through the camp by word of mouth.

Ferit was from the picturesque village of Lin near Pogradec on Lake Ohrid. In this sort of place, you might imagine people fishing, tending vineyards, or rowing boats, but not thieving. However, there was an agricultural cooperative, so there were cooperative thieves, and Ferit’s choice in life was to be one of them. His nickname dated back to the theft of a cow from the cooperative.

Ferit told how the stolen cow had to walk through some mud, and they stuffed its hooves in two pairs of boots pointing backwards, to make false tracks. The next day, the whole village was disgusted to find the cow gone. That was Ferit’s story. Later, he added a detail: the cow had refused to move, and they had put green spectacles on her nose to make the mud in front of her look like grass. That’s why we called him ‘the Cow’, but this nickname would never have stuck, were it not for the shape of his head, his appetite, and the great pendant paunch that gave his belly such a bovine appearance.

The expression ‘our partner’, in the sense of belonging to the same gang, had its origin among the gypsies who used it to identify each other. It became associated with Ferit because, as the years passed, he used it to speak to almost every other prisoner. They too used it to start conversations with Ferit. ‘How are you getting on, partner?’ ‘Fine, partner.’

Nobody had ever heard Ferit talk about a wife or children, his mother or father, or brothers and sisters. This made him the kind of prisoner whom you could not imagine with any kind of life outside prison.

Yet there were also two women whom he regularly mentioned as the loves of his life, Sanije and Xhevrije. ‘Our partner Sanije’ and ‘Our partner Xhevrije’ were phrases that Ferit used to start his stories of them. He never went into feelings of love or descriptions of sex, and seemed never to have experienced such emotions. He would instead boast of how Sanije and Xhevrije were so shrewd and canny in everyday life.

In fact, they were two well-known whores among the camps for ordinary criminals where Ferit had begun his prison life, at a very young age. He’d probably merely heard the ordinary criminals talking about them, and they had become part of his life and his fantasies.

Ferit had come to Spaç after serving several sentences for theft. Then he had been charged with agitation and propaganda against the regime. He was now over fifty, and still had about twenty years left to serve. This was because, after he came to Spaç, he was sentenced to a second term for taking part in the revolt of 1973.

Witnesses to the rebellion said that Ferit’s only part in it was to attempt to loot the food store after the occupation of the camp. He didn’t abandon his old trade even as a political prisoner.

The expression ‘our partner’ which the political prisoners used ironically, implying membership together with Ferit of the same pack of whores or thieves, seemed to aid communication on both sides. But there was in fact a great gulf between Ferit and his fellow-prisoners. ‘Our partner’ was a rare beast, who lived in the camp entirely according to his own laws; he used this expression more as a mask for his activities, because he knew that nobody considered him their friend. Nobody was ever seen to share a bit of bread at the same table with him. Most prisoners spoke to him only either to prompt a joke, or out of fear that he would steal from them. But nobody was safe from his pilfering; Ferit was totally unable to resist the temptation to pinch anything that caught his eye.

* * *

Ferit most often plied his trade in the washroom. It had three sections: dishes and clothes were washed in the middle, and the lavatory cubicles and showers were on either side. The washroom was one of the busiest places in the camp, because all three shifts came here at different times to wash their dishes. There was an incessant coming and going to the latrine or to wash clothes, with people also waiting in line for showers. The water fell in trickles through holes drilled in pipes, which were positioned above a sort of broad gutter raised on bricks and cement.

Above the pipes was a set of metal shelves, on which the prisoners placed their dishes or clothes while waiting their turn to wash them in the wooden tubs. It was the shelves that attracted Ferit to this place. He looked out for the flasks or plastic mugs the prisoners left there. These flasks and mugs were very valuable camp items because they were not provided by the authorities, who issued only one aluminium bowl and a spoon. Families had to bring them. They were extremely handy: the flask held drinking water or oil, and all sorts of things went into the plastic mugs. Ferit would hover about the washroom for hours on the lookout for somebody who might forget his things while absorbed in conversation, or in the lavatory. Then he would snatch his loot, stuff it in his bag, and vanish. The prisoner might notice immediately, or only the next day when he needed his flask or mug again. Then he would remember leaving it on the iron shelf. If he didn’t find it there, his first thought would be to ask Ferit.

‘Ever seen a flask round here, our partner?’

‘No, partner.’

‘There’s a mugful of sugar for you if you find it, partner.’

‘Let’s have a look, partner. I saw a flask, but I don’t know if it’s yours.’

Of course, you had to hand over a portion of sugar or oil for Ferit to produce the utensil.

The washroom was also the place where Ferit was caught and ended up in solitary. This was mostly on account of Pjetër Koka, the most cunning of all the guards in tracking down prisoners’ breaches of the regulations. Ferit was one of his favourite quarries. Pjetër would play cat and mouse with him, stopping him regularly and taking him to one side for a close body search. Ferit wore a camp-issue jacket with layers of patches stitched one over another. These patches also served as pockets, so he had two or three times as many pockets as on the usual camp jacket. He would hide stolen oddments in these patched pockets, which were always filthy, and secrete larger items in a bag made from the same duck cloth, also dirty and patched. In spite of the disgusting grime, Pjetër Koka thought nothing of stopping Ferit and searching him. First, he would thrust his hands into the countless pockets, and then order him to open his bag.

It was unusual for Ferit to get away without some contraband being found on him. What didn’t he hide in his patches and pockets! Besides cigarette papers, which he traded freely, you might find razor blades, little pieces of mirror, nails, and stones. A sliver of razor blade or a fragment of mirror was enough to send you to a punishment cell for a month.

Pjetër Koka might let him off for a nail in his bag or pocket, but whenever he found him with a tiny mirror, he sent him straight to solitary.

Ferit’s trade in mirrors was one of his most successful enterprises. Nobody knew where he found them, but he always had a few in his bag. The ban on mirrors in the camp was inexplicable, because there was no shortage of ordinary window glass that could be used to cut things. Some said it was to prevent signals being flashed outside the camp, and others that they could be used to blind the soldier in the watchtower in the course of an escape attempt, but the most likely reason was that it was one of the authorities’ attempts to reduce all forms of pleasure to a minimum, like the ban on wearing civilian clothes.

The prisoners could not resist the desire to see themselves, even in a tiny fragment of glass that showed only a part of your face. This made the trade in mirrors one of Ferit’s most lucrative enterprises. Nobody knew where he found them, but if you asked him Ferit would certainly bring you one. Some prisoners said he stole them from the guards’ pockets, broke them, and sold each fragment for several packets of tobacco. Ferit had his own mirror too, a little larger than the ones he sold, and you could often find him studying the deep furrows in his brow and the fatty bags under his eyes.

Ferit always submitted abjectly to Pjetër’s hunting zeal. It was perhaps this very subservience that excited Pjetër’s sadism as he searched him with a sour smile, certain of finding some illegal trophy. Pjetër never imagined that Ferit might resist him, and still less that this ragged figure might take his revenge one day through a fantastical story, which would turn his sadistic gratification to fury.

* * *

The camp of Spaç had four punishment cells, each about two metres long and one and a half metres wide. The inmate had to sit there the whole day, without any respite apart from the three meals, each followed by a trip to the lavatory and the issue of a cigarette. He was deprived of newspapers, books, the radio, electric light, and all food that came from his family. He was given only one ladle of broth in the morning and at midday, and one ladle of sugarless tea in the evening, with a chunk of bread. The only light in that concrete box came from the small spyhole in the door, and after dusk this was not enough to distinguish the face of a person opposite you.

Pjetër Koka called the cells ‘nests’. He would threaten prisoners by saying, ‘Do you miss the nest?’ In summer, he would shove four or five men into each of these nests, where they sweltered in the stifling heat. In winter, he would put in one or at the most two, to prevent them warming each other with their breath and body heat. Many prisoners preferred a humiliating beating, or several hours in handcuffs screwed tight to the bone, to time in the cells. After one month in the cell, you needed two months to recover your strength.

These nests probably encouraged Ferit’s rampant imagination, not only because of the extreme privations of the tiny cell, but because he had so much less chance to steal or eat. Once he came out of the cell with a dream that prisoners told to each other for a long time afterward. In his dream, Ferit had seen the craggy hills of the mine turned into mountains of pilaff. In the middle, there was a lake of yoghurt, and Ferit had eaten and drunk from these hills with a spoon made of a mine wagon. It was not clear whether this was a dream, or something that Ferit had made up, but for a long time it transformed the landscape of Spaç in the prisoners’ eyes.

Ferit devised a lot of these fantasies, but didn’t circulate them himself. He merely announced them when they came to him, and then somebody would pick them up and spread them round the camp. He would never retell them unless asked, and then only after persistent encouragement. However, just like his expression ‘our partner’, these dreams too were a mask. Nobody could discover what really went on in this man’s mind. Most of Ferit’s fellow-prisoners found entertainment in his stories, but our partner remained an outsider, entirely isolated. He never talked to anybody for more than a few moments at a time, and then mostly to prisoners wanting to hear his fantasies yet again, or to trade a mirror, cigarette papers, or a stolen plastic mug.