Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The people who talk about their lives in this book represent a creative, dissident Ireland. They are artists, writers, map-makers, weavers, water-diviners, teachers, environmentalists, farmers, wood-cutters, gardeners, travellers and monks. Some continue ways of life that have existed for generations; others have chosen to live and work in ways that are experimental, exploratory, and always singular. The choices they have made prompt us to reflect on our own choices. These thirty-two portraits in word and image provide an alternative view of the possibilities of life in Ireland, and a bracing antidote to the banalities of the consumer society.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 258

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1999

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

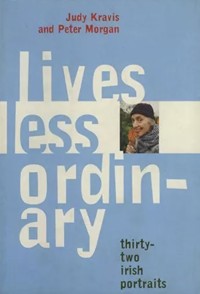

Lives Less Ordinary

Thirty-two Irish portraits

JUDY KRAVIS & PETER MORGAN

The Lilliput Press, Dublin

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

THE PROBLEM IS THE SOLUTIONMarcus McCaberuns The Whole Ark permaculture centre

HERE’S JOEY BLOCKJoe O’Mahonyis a woodcutter and maker of hurley sticks

YOU KNOW THE WAYAlice Maheris a painter

THAT’S MY MAGICPat Liddy,water-diviner, has always lived in the same house in County Clare

HOME LIFECarmel and Pete Duffyeducate their children at home

BEYONDTim Robinsonis a writer, map-maker and visual artist

ALL OF CREATIONWillie Kingstonhas created a sanctuary on his dairy farm

WE’RE REGANSThe Regans,two sisters and a brother, are traditional farmers

A CONVERT FROM NOTHINGMlives as a solitary

A LIFE IN COMMONSéamas de Barra and Patrick Zuk,composers, live without phone, TV or radio

ON THE WESTERN EDGE OF NOWHEREJimmy Dowds,ex-fisherman, works with the Beara LETS scheme

RUSH AND BUSINESSCormac Boydellis a ceramicist living at the end of a peninsula

ANYTHING STRANGE OR COMICAL?The Gogginsare an extended family of travellers

WILL THE PARACHUTE OPEN?Conal Creedonis trying to stop running a laundrette in order to write full-time

DING DING, WE’RE OFF AGAINJudith Evans and Arthur Watsonhelped start the East Clare Community Co-op

GOING BACKWARDSJohn O’Neillruns courses in traditional building methods

WELCOME TO THE BUCKET ECONOMYJudith Hoadand her husband Jeremiah live without plumbing or electricity

REAL REALITYTom O’Byrneis an environmentalist and consultant

VOICES FROM COOLMOUNTAINKatrin and Moiralive in a community in West Cork

THE MADONNA MANJimmy Neffpaints and repairs plaster statuettes

THE BEST OF THE ENDIan and Lyn Wrightlook after the bugs and critters of twenty acres

BLACK AND WHITELily van Oost,artist, sculptor, weaver in the Black Valley

SILENCEFather Kevin and Father Denisare Cistercian monks

ONE BLACK BEETLE KNOWS ANOTHERPatrick Lydonis a houseparent at a Camphill community in County Kilkenny

LUXURY VIEWING THEATRENoel Spencegave up teaching and built a cinema in his garden in County Down

A THOUSAND-YEAR HORIZONMary and Richard Douthwaitebuilt their own house; he writes on economics

DANGEROUS ASPIRATIONSJoe Comerfordis a film-maker

SIMPLIFY, SIMPLIFY, SIMPLIFYChuck Krugeris living out his dream on Cape Clear

THE NAME OF THE WEEDFreda Rountreeruns a tree nursery in County Offaly

A BROAD, GENEROUS AND TRUSTING WISHBernard Loughlinis director of the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig

COMMON SENSEJohanhas been building a windmill for ten years

WHAT HAVE THOSE MOUNTAINS WORTH REVEALING?John Moriartyis a writer and philosopher living in Kerry

Copyright

Introduction

The people we talked to for this book have all made unusual choices. They’ve done different, as Carmel Duffy says. They’re content not to feel part of the mainstream. For many the choices were dramatic – or so their friends told them! They have given up jobs, careers, and sometimes the habits of generations. In our conversations they reflected on the lives they lead, the work they do and how well they like it.

The process of finding them was serendipitous and organic: chance encounters, suggestions from friends, hearsay. One black beetle knows another, as Patrick Lydon says. These are not people who seek to proselytize – they don’t necessarily want more people like themselves in the world. Andy Warhol’s prediction that soon everyone would be famous for fifteen minutes is far from their thinking. Their lives are outwardly quiet; their houses do not shout at the passer-by, and they do not seek to make headlines.

Although their lives may be lived at a tangent to the mainstream of our society, they are not cut off from it. They all buy and sell to some degree. They produce. But they don’t worship money. By the way they live and work they show a scepticism about those social structures that attempt to control them. Frequently they set up their own structures, like community co-ops and home schools. Most of them create their own employment and work at home, or close by. Most produce things with their hands. What they produce is integral to their lives, as well as a source of freedom and pleasure.

Many of these people make us think of a past we know or wish we knew. A past is what you can mentally encompass, it has a wholeness the present seems to lack. It’s hard to interfere with the past. A family of travelling people, a Camphill community, a hermit, present a simplicity that looks utopian – a memorial to the past or a blueprint for the future – unless you’re living in it, in which case it’s simply life.

Many of them live on the land. Some are willing solitaries, who like their own company; for them solitude is not a black hole, it’s a daily pleasure. Some want to change society, actively, as well as by the example of the way they live. Some live a simple life because they always have and it suits them. Joey Block, woodcutter on his own patch, knows where to put such of the modern world as does not meet his case – out the door.

Our conversations with the people in this book often stretched over several days. The portraits are edited transcripts of their words – with the exception of two or three cases where a tape recorder would have been intrusive. As each portrait records a particular moment in a person’s life, we have chosen not to indicate the changes that have taken place since we met them.

This book is a tribute as well as an exploration. In the late twentieth century it is a great achievement to walk to a different drummer. There’s so much din from society’s big drum. Fifty years ago in Ireland there were hedge teachers who went from place to place teaching, playing music, telling stories. The people in this book are the hedge teachers of our day; they pop up out of the blue, they represent no one except themselves, and then there they are, gone.

Judy Kravis

Inniscarra, Co. Cork

Marcus and Kate McCabe, with their two childrenTyrone (Toto) and Róisín, are creating a permaculture centre, The Whole Ark, on eight acres of formerbog land on the Monaghan–Fermanagh border. Wetalked to Marcus.

The problem is the solution

I grew up around here, right on the border. County Fermanagh is across the other side of the pond – and it’s directly south! And over there to the east is the South, if you see what I mean. We’re here about three or four years now. We were two years up in my father’s old home, up the mountain, near Lacky Bridge – the one that was always blocked, that got all the publicity. It took us an hour to travel three miles to visit the parents. The military presence, the whole atmosphere of the North, of the border, you become aware of it from when you’re a small child. Toto used to be terrified of the helicopters.

If you go half a mile from here there are three guards standing waiting for mad cows to come in from the North. And that’s another story: the beginning and the end of agriculture, and it’s probably been coming for an awful long time. The land is almost derelict. Policy is incoherent, when you look at headage payments, and soil erosion from overpopulation of sheep. There’s a war on the resources of the planet. I was in a place in Sligo yesterday, and a hedge had been taken out and burned. There was enough timber in it to keep a masonry stove burning for about three years. No value is placed on things. It’s easier to go down and buy a bag of coal than to go to the trouble of cutting up the wood.

The land lacks people. The kids go away to the city, because the parents are struggling to make a living; those same children are still supported by land; the food is there for them in supermarkets, but the connection is completely obscured. So we’re looking at ways in which people can either move onto the land and make a living, or stay on the land, which means looking at the way land is owned.

The international permaculture convergence four years ago was in Scandinavia. We were on a farm in Norway where the line of father and son went back to the year 800 in an unbroken line – father to eldest son. Primogeniture is the basis of our legal system. There’s a real hatred of farms being split up in Ireland, it goes back to the Famine, and the penal laws; you had to divide land equally among your children. Before that, land was owned collectively, by clans, and people had a licence to use land, or to move animals through land, like pigs or geese. I think we can set up systems like that now. People can collectively buy land, own their house, their garden, and then have access to commonage, which is managed collectively. Talking about land reform is crazy. People fight wars over that sort of thing.

If you have two hundred acres of land owned by forty or fifty families, then all the milk that’s produced supplies everybody within that community. And the shit from those cows can go on to someone else’s business, like energy production. Start making connections between the people and the livestock and the plants within a system. Two hundred acres is a huge area and can produce a lot of food. I would create land trusts, so that the land is owned by a trust in perpetuity, and is governed by elders who are elected to be responsible towards that land, whether it’s eight acres or a thousand acres. The trust can lease out homes long-term, so you’re not going to be evicted. You have your garden, but you have access to other land as well, so that you can fly bees through it, or run geese through it, or sheep. An awful lot of resources can be produced: food, timber, roofing, the bulk materials for building. Monasteries have always done that, and they’ve always been prosperous; because there are more people, they can make much better use of the land resources.

I run courses here on how to do all that. Different sorts of people come on the courses: people who are stuck in the cities, people who are living in the country and don’t really know what to do, people who have come across the idea of permaculture and think it’s generally brilliant anyway. And then there’s teaching by example.

There’s a farmer up the road who comes down to look at what we’re doing. He’ll probably look for another two or three years before he makes a decision. He’s got cows, and he’s realizing that’s coming to an end. He keeps bees, he generates his own electricity, he’s got good respect for his land. He’s told that alfalfa doesn’t grow in Ireland, but he’s got some from us and it’s growing fantastically; so he’s wondering why they’re saying it doesn’t grow here. He’s very interested in trees. He’s considering getting rid of his cows and getting goats, and he’s looking into how to set up a forage system for goats, so they’re not just getting grass, but also tree boughs, and everything that’s coming down from the trees.

He’s willing to experiment, and I think he’s not so rare. There are quite a few like him, dotted about the landscape. You come across them when you start a place like this. They notice you and they come in. My own father was inclined to experiment on the farm in the early years, but the environment was very unfavourable to organics in the fifties and sixties. While I was studying horticulture at UCD, I grew three acres of raspberries and half an acre of strawberries up at my parents’ place. I hate to admit it, but I was using sprays and fertilizers; that was what was done then. As time went on I could see what was happening: the structure of the soil deteriorated rapidly, there was a lack of life. But they taught you in college that everything was going to die and rot if you didn’t use sprays.

In the library at UCD I discovered all this information about what fertilizers were doing to the soil, and the damage pesticides were doing on a global scale. We weren’t taught any of that at college, no, no, no, no, not at all. Then in my final year I organized a debate on organics. It was packed, mostly with academics, even old retired ones had been wheeled out, it was very very heated and lively. That was a landmark for me. I started thinking about fertility and what that actually is. Why do we have to pour so much into a farm in order to get anything out at all? How is it that a forest can just grow and grow and grow, just create more and more of itself?

After I left college I got a job in third-level education, which I could have stayed in till I was sixty-five and had a very easy life. But my conscience wouldn’t let me teach these lads how to spray and how to fertilize their monocultures, and my bosses wouldn’t let me teach anything else. I remember sitting in my office surrounded by all these books about fertilizers and pesticides, and thinking, I can’t do this, I can’t do this – I almost get indigestion thinking about it. My parents were absolutely horrified: I was giving up a good job, and signing on, and what was I thinking about?

I became a campaigner for Earthwatch, and did a lot of trying to get media attention: dumping manure outside the Department of Agriculture, and bringing coffins to the Dáil. I did that for about three years and got very burnt out. You might get a couple of column inches in the Irish Times, but nobody really seemed to care, and nobody seemed to be offering alternatives. At that stage I came across permaculture. I found two books sitting on the shelves at the Centre for Alternative Technology, and I remember flipping through the books and being completely amazed. How to set up Eden in your own place. I couldn’t understand why it wasn’t being shouted from the rooftops. Permaculture is a natural system, it’s like the human garden extended. You’re building up the relationships between plants, animals, and all the other living things in the biosphere are working together to create something we can use – or not use.

Permaculture is about how things are placed. The fact that our vegetable garden is immediately outside our kitchen is not an accident: you go out, pick your meal, bring it in and make it. We made that lake out there. This was a bog, an unusable field. So we dug out a lake, we made dry land on which to build a house, and we’ve raised the water table – I’m very proud of that. You’ve got all these wetlands being drained all over Ireland. The problem is the solution. You’ve got wet land, well, that’s the solution, keep it wet, make it wetter. We’ve loads of rain, so dig out ponds, get rid of the mad cows and eat a bit more fish. The lake reflects light onto that back wall in the wintertime; you’re getting 80 per cent reflected light, and on a frosty, clear day, it’s warm in the middle of the day in the house. The geese range through and keep all the mulch plants down among the fruit trees. They mix in very well. The pig is a rotavator. All these things come together as a system.

Our plan is that this building we’re in now will be the teaching building, it won’t be our house. We’re going to build a straw-bale house next year, so we can do more courses here. We want to move in the direction of an eco-village, so that more people can live here, owning their own houses. I was in a rural college in Draperstown recently, which has about two or three million in funding. I was really interested; it sounded as if they were doing what needed to be done: setting up a model. It was a hundred and fifty acres of forest, and well-architected buildings with courtyards and restaurants, but not so much as a chive, not a lettuce, not an animal. If you come to our place to do a course, you’re going to be fed from the garden. It’s important for people to see that we’re living from what we grow, that we have a good life, we’re warm, the water’s hot, and the work is very diverse. You don’t have to work hard, but you’re very busy.

We’re taught from an early age to tolerate drudgery, sitting still for six hours and learning things by heart, when actually playing is learning. Children instinctively play and learn what adults do. When we’re playing we’re learning. Adults too. Play and learn what children do! Play at what you like doing. People need to know what they want to do, what they like doing, what they enjoy doing, what they would pooter and footer at if they had lots of time to themselves. I love pottering around in the polytunnel. I love digging, sawing, building, planting, contact with animals – I love talking!

So many people find it hard to know what they like doing. The media create such a clutter you can’t hear yourself. And we can distract ourselves so easily If there’s a television in the room, it deadens everything. We’ve a neighbour who calls in here to get away from the television in his own house. He sits here and smokes his pipe, and if there’s nothing to be said he doesn’t say anything. That’s a real country thing. It’s like the giant in Oscar Wilde. The selfish giant went to meet another giant down in Cornwall, and he left after seven years because they ran out of conversation. It was a long conversation but it came to an end. So he left.

Joe O’Mahony (a.k.a. Joey Block) fells trees, cutsplanks, sells firewood and makes children’s hurleysticks. He’s always on the lookout for a good ash tree.

Here’s Joey Block

The way I look at it is this: the world’s a jigsaw and people are all comical items in it. Here’s Joey Block down at Ardrum with his wife Bernadette and four children – three boys at home and the girl, she’s married in Cork – as well as, at the last count, eleven cats, four dogs, Minnie the goat and Alfie the sheep. Here’s small Joey on his patch where he’s reared his family these thirty-two years – how I got here, that’s a fairy tale – third-generation woodcutter, Joey works on his patch of ground, keeping away quiet and original, when the big guys attack!

He lets the word rest, he lets it travel around his land, his trees, his sheds, hismachines, down the lane he picked and shovelled himself in 1958.

And listen to me here, d’you know what I said to the big guys? I said, you come in here with your machines and you’ll have to mow through the six of us. And I went to the priest and I said: You’ve got room for six coffins in here, haven’t you? The family’s reared and Joey’s going nowhere. I said to the big guys, you’re not just taking on Joe Block, you’re taking on a wife and family.

The big guys were trying to knock his trees, widen his stream; he was part oftheir scheme and they were not part of his. He took them to court; he calledtwenty-seven witnesses and would have brought in Minnie the goat; he spokehis own defence, and won – and he’s proud.

If you had a man with the book-learning standing right here now and he saw the family that’s grown now and the hill behind with that sun on it, would he say that Joe and his family should be moved on up the Tower road so the big guys can complete their scheme? He would not. And neither would the man up there. If there was a man up there. D’you believe in the man up there?

I’ll tell you now how I came here. I came out with the wife and the wife’s mother, just out in the car for a drive one Sunday in 1958. We stopped at the post office to buy – I can remember exactly what we bought – one of those chocolate things, and I asked was there any handy cottage about that was empty? The old fella in there said to go out the door and turn left then left again and up the lane – I told you it was a fairy tale – and in the end we were given the cottage with the bit of land – no paper, no signatures, no agreements. And we came in and reared the family. Thirty-two years. I fall the trees and I make the hurleys, and I don’t want anything only to keep things going as they are.

Alfie! he calls to the sheep who’s tied to a tree down the lane. Alfie! He usually answers. On the third call, Alfie does.

Alice Maher is a painter. She grew up on a farm inCounty Tipperary, and currently lives in an ovalroom in a Dublin square.

You know the way

You know the way in school you always get left in charge because you’re the biggest girl in the class – people believe you when you’re big. I had independence foisted upon me. I went to Spain when I was sixteen to be an aupair, and I went on my own, changing planes and so on; this didn’t seem to be a problem for me, yet my sister Christine, who was small and had been sickly as a child, had to be driven everywhere. So I think it began when I took on the mantle of responsibility. I didn’t like it – I don’t like it now – but every family needs a safety-valve and in our family that was me, someone in whom the others can invest their wishes for freedom, a boiling pot.

I was never ever afraid of anything in my whole life. I don’t think about putting down roots or being older and sicker. I prefer the insecurity, if that’s what it is; that’s the way I live best. When I made the decision to go to art college, I trusted that the money would come. And it usually has. I didn’t really choose to be not married, not in a house, not having a job. It wasn’t out of defiance. I’ve just been really busy! It’s as if I arrived here at this age very quickly. I don’t remember what happened in my twenties. You know how it is, you wander round the world, money-making, dope-smoking, hitchhiking, living in tents. I’m thirty-eight now, going on thirty-nine, and I’ve never owned anything – except a car, for a while. I’d like to own a car again, I like mobility. The minute I buy a house the trouble will start! That must be the way it was meant to be for me.

I never made the decision to be an artist; there’s nothing as bad as deciding ‘I want to be an artist.’ I’d never met an artist when I was growing up, but I was convinced I could do anything. My mother was very creative too; she had a beautiful garden. And my parents never put up any serious objections, like, How are you going to live? They thought, she can look after herself, she’s invincible. It was probably luck, too. And I could draw, I could always draw. Just copying things.

I’m very driven. Not that I’m driving towards point A, I’m just driving. Getting known isn’t the driving force – but I wouldn’t want to be not known either. I like people writing about my work. Critics set you in context and it gives you back a sense of yourself, situates you. I’ve no interest in working blind, like a mole, just spitting out work. I think it’s important to be known. Though being known can be hard because you’re up for hatred as well as love!

I don’t like being solitary, I always have loads of company, and I’m more likely to be in a relationship than not. I like having fun, partying, you know. Of course I’m on my own when I work. For some years now I’ve lived and worked in the same place. I do some teaching – which isn’t really related to making art. I like a little bit of teaching – you’re talking, it’s company. Work is a strange state: it’s not that I feel happy when I work, more like, time doesn’t exist. That’s happy. Because you’re unconscious. Not like sleep. You can see and feel in lots of dimensions. Things I make are either really small or really big, there’s no medium.

This picture here is about growing bigger and smaller. People think my pictures are conceptual but actually they’re almost experiential. I didn’t decide a mountain for this picture, I had no idea what I was going to do. I just put on a ground, and then I did the mountain. From a distance you see a mountain, and then maybe you spot the puff of smoke at the top, then you come closer and you see the little girl with a fire next to her. When I put the little figure on the top I got a fright because I thought she looked so lonely, so I put the fire on to keep her company – it’s a nice puff of smoke, like she’s sending up signals or something. She’s very happy up there, the way she’s lying, she’s very relaxed. I’ve been painting little girls for a long time, but these are positively miniature! It’s not like I’m trying to disappear, though. These creatures are absolutely huge to me, if you can imagine that. Would I like to be on the mountain like that? I think I am there.

Pat Liddy is a water-diviner, beekeeper and retiredfarmer. One trouser leg is clipped back ready for thebike. He lives in County Clare, in the house wherehe was born. His mother was there too till she wentto live with his sister in Whitegate. There are aboutfifteen clocks in the room, cuckoo, rollerball andwall-wagger. An old valve radio is plastered into onewall.

That’s my magic

Most of the clocks came from Germany. There was one fella came here looking for a spring. He fell in love with a sheepdog pup I had in the yard. So I gave it to him and then he came back and gave me a clock. After that people kept bringing clocks when I found them springs. Finding springs. That’s my magic. You’re not supposed to charge for finding a spring for people because it’s a natural gift.

I don’t think my father had the gift, but he died before I knew I had it. It’s not something you can learn at school. When I left school I hardly knew how to read the paper. There was a teacher by the name of Miss Hawkins, but she was wicked. She gave me such a beating down the head that when I got home and opened my mouth it hurt my ears.

I’ve good hands. Anything I see done I could nearly do it after that. Most things about the place I’ve done myself. Or haven’t done because I didn’t have the price of it. I worked the farm all the time, doing everything that was ever to be done, train horses, plough, cut hay, cut turf. I could make any sort of cock of hay. When I was young I done everything. I ferreted rabbits. A shilling apiece. Did you ever see a ferret? You got into the pictures for a shilling. And maybe have a smoke as well. That time people would live only for the local shop being so obliging and giving them credit for a month or two. I don’t think people are happier now they’ve got more money.

I did work hard. And my parents worked harder. If you had the weather you had to avail of it. Your biggest delight was after a day’s work if you had a field of hay all stacked and it rained that night. You slept very happy.

I rent the farm out now. But I stay here, I live away, keeping going nice and gentle. I cook on the fireplace. I boil the kettle over the fire. Cook my eggs in a pea tin. I have an old gas cooker but I never use it. I haven’t got a car. I never liked driving. I have a tractor but I don’t like driving on the road. In a tractor you hear nothing. In a bicycle you hear everything. The furthest I ever went was Dublin. I went to an all-Ireland football final in 1963. I didn’t like Dublin at all. I couldn’t sleep at all with the traffic, the noise. Killarney was the furthest south I ever went. My sister and her husband are trying to bring me to England for the last twenty years. I’d go the odd time to Limerick, for a hurling match, or something I couldn’t get in Tulla. I’m not a big shopper. If something’s a bit worn I’d rather leave it as it is. Young people today are born with money. They know nothing else. They wouldn’t know how to hang a kettle.

I’ve got the TV though. Since they came out. I like Coronation Street. ’Tis very funny. I like a good yarn, an insulting answer. Coronation Street is like Tulla. I go into Tulla three or four times a week. I go to a ballad session maybe Wednesday night. And I like a good conversation. There are some characters there. You wouldn’t need to write a script. Their answers are fantastic. I used to go to films, then I saw a film being made when I was in Dublin that time, and I never went to a film after that. All the crews, all the cameras and the equipment out on the street. You saw what you’d see on the screen but you saw the back of it, behind the scene. It’s a bluff job, sure.

I heard an old guy say one time you should always walk agin’ the people. If a hundred people are walking that way and you didn’t like it, you walk the other way.

Would you mind if I watch Coronation Street now?

The Duffys, Carmel, Pete and their nine children,