Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

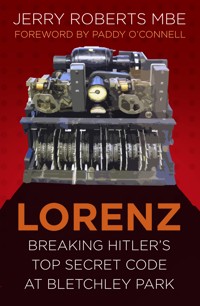

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The breaking of the Enigma machine is one of the most heroic stories of the Second World War and highlights the crucial work of the codebreakers of Bletchley Park, which prevented Britain's certain defeat in 1941. But there was another German cipher machine, used by Hitler himself to convey messages to his top generals in the field. A machine more complex and secure than Enigma. A machine that could never be broken. For sixty years, no one knew about Lorenz or 'Tunny', or the determined group of men who finally broke the code and thus changed the course of the war. Many of them went to their deaths without anyone knowing of their achievements. Here, for the first time, senior codebreaker Captain Jerry Roberts tells the complete story of this extraordinary feat of intellect and of his struggle to get his wartime colleagues the recognition they deserve. The work carried out at Bletchley Park during the war to partially automate the process of breaking Lorenz, which had previously been done entirely by hand, was groundbreaking and is recognised as having kick-started the modern computer age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 369

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LORENZ

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Jerry Roberts, 2017

The right of Jerry Roberts to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB 978 0 7509 8204 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

A SELECTION OF TRIBUTES TO CAPTAIN JERRY ROBERTS

Captain Jerry Roberts MBE was a true gentleman and – to the last days of his long life – an outstanding ambassador for Bletchley Park. In World War Two he was a key member of the team who deciphered the most secret communications that changed the outcome of the war. Unfailingly modest about his own achievements, he was committed to the end to achieving recognition for the work of his colleagues and the contribution of all those who worked at Bletchley Park. He will be greatly missed. Our thoughts are with his devoted wife Mei.

Sir John Scarlett KCMG OBE, chairman of the Bletchley Park Trust, responding to the news of Jerry’s death.

Jerry remained, into his high 80s and early 90s, a terrific speaker who could hold large audiences spellbound. His intelligence, humour and generosity endeared him instantly to all who knew him, whether slightly or well. He leaves his family, many friends and countless admirers worldwide.

Professor Susanne Kord, University College London (UCL).

Today Bletchley’s fortunes have dramatically improved thanks, in no small measure, to Jerry’s work on so many fronts. And so it was hardly surprising that Jerry, at the end of his life, was honoured several times for his historic achievements. Almost at the end, he wryly remarked to me; ‘Funny thing Charles … sixty years later I still find myself trying to “break” car number plates!’

Jerry, we all owe you a great debt, and we miss your smile and your hat!

Lord Charles Brocket, a friend of Jerry and Bletchley Park, TV presenter and journalist, talking at Jerry’s memorial service at St Martin-in-the-Fields in London.

Jerry was an extraordinary man and he made a real impression upon me – I felt his presence and spirit every day that I worked on the ‘Codebreakers’ film. In fact, his honesty, attitude and belief in Bletchley – and his need to tell those stories – all combined to give that programme a moral core and sense of purpose and decency which made for something very special. As such it couldn’t have existed without him and I hope it serves as one of many tributes to him.

Julian Carey, BBC film director and producer of the 2011 BBC Timewatch programme on the Lorenz story, ‘Codebreakers: Bletchley Park’s Lost Heroes’.

We all owe an immense debt of gratitude to you and your colleagues who worked tirelessly throughout the war to decode information vital to the Allied efforts. Your work helped not just to save lives, but to bring this dark period in our history to a swifter conclusion than could have been achieved without your efforts.

David Cameron (British prime minister, 2010–16), in a letter to Jerry Roberts on 21 November 2012.

DEDICATION

To my fellow codebreakers and colleagues in the Testery team at Bletchley Park, who broke every Lorenz code by hand until the end of the Second World War.

To Bill Tutte, in particular, who broke Hitler’s Lorenz cipher system in 1942 without ever having seen this complex machine, which was vastly more secret and significant than Enigma.

To Tommy Flowers, who designed and built a machine called Colossus for speeding up the Lorenz codebreaking – this was the world’s first ever electronic computer in 1944. We all owe a huge debt to his work for inventing the modern computer.

To all those men and women who worked at Bletchley Park where ciphers and codes were decrypted. Sadly, most of them are no longer with us and they have never received the recognition they deserved for their extraordinary achievements.

Finally, to my dear wife Mei, for her dedicated support of twenty-five years, without whom this book would not have been written.

CONTENTS

Foreword by Paddy O’Connell

Foreword by Mei Roberts

Preface

A Brief Legacy of Bletchley Park

Introduction

Part One: The Making of a Codebreaker

1 Life in North London

2 Latymer Upper School

3 University College London

Part Two: Doing My Bit for the War: 1941–45

4 Recruited to Bletchley Park as a Cryptographer

5 Establishing the Testery in 1941

6 Hitler’s Top-Secret Code: Lorenz (Tunny)

7 How Lorenz was Different from Enigma

8 Bill Tutte Breaks the Lorenz System

9 The Testery Breaks the Lorenz Code by Hand

10 How Hand Breaking Worked

11 How the Testery was Assisted by Machines

12 From Lorenz Decrypts to the World’s First Computer

13 Key Decrypts from the Testery and their Impact on the Second World War

14 Why is so Little Known About the Testery?

15 Three Heroes of Bletchley Park: Turing, Tutte and Flowers

Part Three: After the War

16 The War Crimes Investigations Unit: 1945–47

17 Translating a Book from French

18 Fifty Years of Market Research: 1948–98

Part Four: Seeking Recognition for Tutte and the Testery

19 My Six-Year Campaign

20 A Selection of My Talks

21 Meeting Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

22 BBC Timewatch

23 The Turing Centenary Lecture

24 Meeting the Queen Again

25 Interviewed by Katherine Lynch

Part Five: My Personal Life and Interests

26 Knowing Mei

27 My Family and Previous Marriages

28 Hobbies and Interests

Afterword

List of Testery Personnel

Useful Websites

FOREWORD BY PADDY O’CONNELL

They were often signed with the two initials A.H. – Adolf Hitler – and we received them for much of the war.

Jerry Roberts deciphered Hitler’s most secret messages – and there were many others, too, between his top generals, all encrypted on the specially designed Lorenz machine. The information ended up not just in the German High Command where it was intended but on the desk of Winston Churchill too. Jerry yearned to reveal how, but as a codebreaker and a German linguist at Bletchley Park, he was sworn to secrecy for years. Then, as the story of the Enigma machine became much better known, this separate tale of the cipher nicknamed Tunny by the British often became confused in the public mind and merged into one.

It was a staggering achievement, as statistically impossible as it was unimaginable. Whilst this brainpower was later boosted by machines (specifically Colossus), much of it still was done by hand. Jerry wanted future generations to understand how key linguists, codebeakers, engineers, mathematicians and more worked together in a feat of reverse-engineering. The team at Bletchley cracked Lorenz without ever seeing the twelve-wheeled device.

Jerry worried that this risked being forgotten or misunderstood. He wanted to name the names of the key people involved, and to describe in detail how the information they mined was passed not just to Churchill but to the Allied commanders planning for D-Day and to the Russians too.

I met him many times with my mum, who was a Wren working at Bletchley Park. This is the account of one of those few men in life who wants all the others to get the credit. We promised him to help get this story told, and it’s as humbling as it is an honour to write these few lines of introduction.

Paddy O’Connell, presenter BBC Radio 4 and BBC Radio 2, 2017

FOREWORD BY MEI ROBERTS

My husband Jerry Roberts died on 25 March 2014, aged 93, shortly after completing this memoir. BBC News and almost every major newspaper from The Times to The New York Times, national and international, featured a formal obituary.

During the final six years of his life, Jerry dedicated an enormous amount of time and effort to raising public awareness of Bletchley Park’s major achievements on the Lorenz cipher, and the extraordinarily important work carried out by his team at Bletchley Park, much of which is still largely unknown to the public. He travelled extensively, giving public talks and working tirelessly for better recognition of his colleagues. Jerry was awarded an MBE in 2013, but he hoped that one day his whole team would be recognised for their contribution.

He was calm, humorous and a great character, with generosity and determination – an outstanding Englishman. I sorely miss his amazing and unique stories. I have such a vivid memory of Jerry talking with Her Majesty the Queen in July 2011 at Bletchley Park, recounting his experiences of breaking the Lorenz code. I heard him tell the Queen what it was like to read messages signed, ‘Adolf Hitler, Führer’, before they were even received by the German High Command in the field. Who else has stories like that?

Jerry was an amazing man and played a significant role in the war for his country and for Europe. He remained modest, despite his phenomenal achievements. His star will shine in the sky forever.

Sadness is never overcome, but the outpouring of recognition and admiration for him and his work have helped me through each day and made the sadness somehow easier to bear. On behalf of our family, I thank you all sincerely from the bottom of my heart.

Goodbye, my dear Jerry, may you rest in peace.

My heartfelt thanks to Margaret and Paddy O’Connell for introducing me to Heather Holden-Brown (HHB Agency Ltd) and for Heather’s help in publishing Jerry’s book.

Mei Roberts, 2017

In loving memory. A portrait of Jerry sketched by Mei

INTRODUCTION

Captain Jerry Roberts entered the ranks of the army as an officer in the early stages of the Second World War. Fluent in several foreign languages, he was a founding member and senior cryptographer in the Testery, the special unit at Bletchley Park tasked with the daily breaking of Lorenz (called Tunny by the British), the Nazis’ highest-level communications cipher system, which was used between Adolf Hitler and his top generals in the High Command. Decrypts from Lorenz enabled British commanders to know what the Germans planned, and the decisions they made helped Allied forces to hasten the end of the Second World War by at least two years, saving tens of millions of lives. The work on breaking the Lorenz cipher also led directly to the development of the world’s first electronic, programmable computer.

Following this remarkable start to his career, after Bletchley Park Jerry Roberts was a member of the War Crimes Investigation Unit in Europe (WCIU), where he helped to track down Nazi criminals and bring them to trial. When Jerry left the army, the Official Secrets Act prevented any discussion of his contribution to the war effort with both Bletchley Park and the WCIU. His career was slightly in the doldrums, until a chance encounter with an ex-colleague from Bletchley Park sparked a new and unexpected career in international market research. Roberts established the first market research company in Venezuela, and later set up his own companies in the UK and Europe.

In the final six years of his life, Roberts campaigned tirelessly to raise public awareness of the importance of the Lorenz story, which was declassified only at the beginning of this century. In contrast, Enigma became public in the 1970s. Lorenz had wrongly been overshadowed by the fervour surrounding Enigma, due to the highest levels of security imposed by the Official Secrets Act.

Jerry felt it was his duty to ensure his colleagues in the Testery received their rightful recognition, in particular Bill Tutte, who broke the extremely complex Lorenz cipher system without ever having seen the cipher machine. Tutte died in 2002, without receiving public recognition nor any award for his achievements. Tommy Flowers, who designed and built the Colossus, the world’s first programmable electronic computer, died in 1998 – also without gaining any recognition.

At age 93, Roberts was the last surviving Lorenz cryptographer. He was honoured several times for his historic achievements in his final two years. This autobiography charts Roberts’ long and varied life, simultaneously personal and historical. It is a first-hand account of virtually unknown twentieth-century history – a history that, without Roberts and his colleagues at Bletchley Park, might well have turned out very differently.

A BRIEF LEGACY OF BLETCHLEY PARK

Bletchley Park, once Britain’s best-kept secret and home of the codebreakers, is today a heritage site and museum, with exhibitions, activities, events and attractions for visitors from all over the world. The Park’s breathtaking Second World War codebreaking successes helped shorten the war and saved tens of millions of lives. After the war, General Eisenhower (later US president) said that Bletchley decrypts shortened the war by at least two years. Sir Harry Hinsley, one of the top codebreakers at Bletchley Park, also said the war had been shortened ‘by not less than two years and probably by four years’.

Much of this was down to the work of Bill Tutte, who broke into the Nazis’ highest-level cipher system, Lorenz SZ40/42 (codebreakers called it Fish or Tunny) and allowed codebreakers in the Testery to break those top-secret Lorenz codes – amounting to around 64,000 intelligence messages during the course of the war. Lorenz was only declassified at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Bletchley Park was also the birthplace of Tommy Flowers’ invention, the Colossus – the world’s first programmable electronic computer – in 1944. Its only purpose at that time was to speed up one stage of the Lorenz codebreaking process and to try to win the war. Bill Tutte and Tommy Flowers changed the world, but then they disappeared from history because of the highest level of secrecy demanded by the government. There is an amazing replica of the wartime Colossus by Tony Sale and his team which can be seen today at the National Museum of Computing (TNMOC), housed in Block H at Bletchley Park.

During the Second World War, there were two major cipher systems worked on at Bletchley Park: Enigma and Lorenz. Most people have heard of Enigma and Alan Turing, but many have not heard of Lorenz or Bill Tutte. Lorenz was a vastly complex and much more significant cipher system in comparison to the well-known Enigma. Lorenz was kept under wraps by the Official Secrets Act for nearly sixty years after the war – whereas Enigma was kept secret for only thirty years. Bill Tutte and Tommy Flowers are the forgotten heroes of Bletchley Park.

Unlike Enigma, Lorenz carried only the highest grade of intelligence. Tens of thousands of Lorenz messages were intercepted by the British and broken by the codebreakers and linguists in the Testery at Bletchley Park. Messages were signed by only a handful of the German Army High Command, including Adolf Hitler himself.

Breaking into Lorenz gave the Allied High Command significant intelligence that changed the course of the war in Europe and saved tens of millions of lives at critical junctures, such as the Battle of Kursk in Russia and before and after D-Day. If the D-Day landings had failed, it would likely have taken at least two years to prepare for another major assault. Lorenz decrypts made a major contribution to winning the war.

There were three heroes at Bletchley Park: Alan Turing, who broke the naval Enigma that helped Britain not to lose the war in 1941; Bill Tutte, who broke the Lorenz system, which helped shorten the war; and Tommy Flowers, the father of the computer. Britain was extraordinarily lucky to have these three great men in one place during the darkest times of the Second World War.

Bletchley Park’s success brought so many benefits to the British nation, and indeed to Europe as a whole. It also kick-started the modern computer industry, introducing us to the whole digital world of today. For years the wartime contribution of Bletchley Park has been totally undervalued. Only now is it beginning to be properly appreciated, but the story of what went on in the Testery is still largely unknown to many people.

Jerry Roberts, January 2014

PREFACE

This book is about my varied life, including my wartime experiences working at Bletchley Park as a cryptographer and linguist. It came about when my friend Professor Jack Copeland (the leading authority on Alan Turing) encouraged me to write a book about Lorenz and my involvement in it.

I’m very lucky to be alive today. I feel a great responsibility to help in spreading the word about Lorenz, especially for my fellow codebreakers and the support staff who worked with me in ‘the Testery’, the area of Bletchley Park where the codebreaking was done, named after its founder, Ralph Tester. As a team, we broke approximately 90 per cent of Hitler’s top-level coded messages, around 64,000 in total – intelligence gold-dust! I recall their efforts and the contribution that they made, virtually unsung, unknown and unrecognised during their lifetime. Since 2007, I have been seeking better recognition for them, in particular for Bill Tutte.

I am now 93. As you can imagine, it is not easy to write a book at my age; my health and energy have slowed me down and I also have difficulty in writing clearly. I wish I could have started this book earlier. Luckily, with the great help of my wife, I have been able to record my text, and our daughter Chao typed it. It took some time to pull it all together, but it worked.

I would like to thank a number of people warmly for their help and kind contributions:

First, Philip Le Grand, the editor of Bletchley Park Times magazine (2006–13), who has done so much good work for Bletchley Park as a volunteer, always welcomed my articles about Lorenz and helped to revise the text.

Beatrice Phillpotts, a local journalist and editor who works for the Haslemere Herald, provided tremendous support and kept reporting on the Lorenz story to keep the campaign going.

Katherine Lynch, the media manager at Bletchley Park, a journalist and reporter of fine quality from the BBC, helped greatly to spread the word about the Lorenz story in various ways.

Rory Cellan-Jones, the BBC senior correspondent on technology in London, first recognised that Lorenz was an enormously significant piece of history.

Julian Carey, the producer from BBC Wales, made a BBC Timewatch programme in 2011, entitled ‘Codebreakers: Bletchley Park’s Lost Heroes’, which told the full Lorenz story. The documentary received wide acclaim, in the UK and abroad.

Professor Susanne Kord, the head of the German department at UCL, set the ball rolling from the beginning, giving me a platform to speak publicly for the first time about the Lorenz story.

Lord Geoffrey Dear raised my subject to the House of Lords for Justice, but was rejected because it was felt that it should have been dealt with straight after the war.

I give my grateful thanks to all. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank many of those who supported me during my campaign for the last six years. This book is a personal record of my life. Any views expressed in it, of course, are my own. My aim is to keep the record as accurate as I can.

Jerry Roberts, January 2014

1

LIFE IN NORTH LONDON

I was born in November 1920, in a house called ‘Morfa’ in Wembley Park Drive, which is now opposite the main entrance to Wembley Stadium in north London. My parents had arrived in London in 1915 from Rhyl, North Wales. My elder brother Arnold had been born in Wales and was already 7 years old, and my younger brother Frank came along three and a half years after me; we were both born in London.

My father (Herbert Clarke Roberts) was a bank clerk, working in the Lloyds Bank head office in the City. He originally came from Liverpool and had trained as a pharmacist, but had to change his profession as the constant standing aggravated the varicose veins in his legs. He spent the rest of his working life travelling up to the City every day, until he retired at 65.

My mother, Leticia Frances Roberts (née Hughes), was a talented pianist. She played the piano in the chapel at Warren Road, Rhyl, and also sometimes the organ at St Asaph Cathedral nearby. In 1915, when the family moved to London, she left Rhyl with the thanks of the congregation and a handsome clock inscribed to her, ‘Mrs H.C. Roberts, organist of Warren Road Chapel by friends and well-wishers on her leaving Rhyl, January 1915’. The clock still remains with me as a cherished possession. I also still have her beautiful mahogany piano stool with its engraved surround. It is the piece of furniture I am most attached to; within it are some of the sheets of music she used to play to us as children and to herself – she played the piano well.

Rhyl was where my mother was born and the family were originally located. Almost all of my mother’s friends and relatives were from North Wales and we had uncles and aunts (some of whom we never saw) in Lancashire, Chester and Manchester, as well as Liverpool, where my father’s side came from. We were one of the many families who gravitated towards London in search of better opportunities.

There was wholesale movement away from North Wales in the early years of the last century. One uncle went to Chester, where he worked for Crawford’s, the biscuit company. Another uncle, Lou, went to work in the textile industry in Manchester. A third, John, came down to London, to Finchley, where he practised as a doctor. My Auntie Minnie, whose husband was killed in the Great War leaving her with two growing children Gwylmor and Nerys, took over a grocery store with a post office in Greenford, North Ealing. Auntie Minnie’s husband was richer, and Gwylmor was able to buy a car, a relatively rare thing to own at that time, which gave him extra mobility and standing when he went into business and prospered. He also visited the US in the early 1930s when very few people made the trip.

There was yet one more refugee from Wales, our Uncle Edward. He was my mother’s youngest brother. He had a speech defect but it did not prevent him from successfully running a tobacconist shop at Sudbury Hill in north-west London. He lived over the shop and added a second store a few years later. Eventually my mother’s parents came down from Wales to live with him.

We always called them Taid (Welsh for grandpa) and Nain (grandma). Uncle Edward lived close to the tube station at Sudbury Hill, one stop from ours. We used to see them from time to time, as they lived nearby, about fifteen minutes’ walk away. Taid was always impeccably dressed in a full suit, complete with buttoned-up waistcoat, and a silvery beard always carefully trimmed. Nain was rather heavily built; she invariably wore longish skirts of heavy and dark materials. The chapel was taken very seriously in those days; our family had closer ties to the chapel than most because my mother played the organ on Sundays for some years.

On my father’s side, there was my grandfather Robert William Roberts and grandmother Maria Roberts (née Clarke). I never met Granny Clarke, but I heard a lot about her. I have a portrait of her (c. 1850) left to me by my parents. She looked a really formidable character – a true Victorian matriarch. She must have had quite a lot of authority and respect in the family. All of her sons and her grandsons (and us) carry her name – Clarke.

I also have an original newspaper cutting of one of her sons, Frank Roberts, from the front page of the Daily Sketch (the Daily Sketch merged with the Daily Mail in 1971), which is dated Friday, 9 January 1914 and entitled ‘England may well be proud of these gallant officers’, with an article by an American writer. Uncle Frank was a third officer of the Booth liner Gregory in the Royal Navy, based in Liverpool. The newspaper wrote that he was a hero. Apparently he dived into icy water and saved five Americans from the wrecked oil ship Oklahoma. He later transferred to the army and was killed in action in France in 1916. He was buried at the Woburn Abbey Cemetery at Cuinchy, between Béthune and La-Bassée in the Pas-de-Calais. He is a family member of whom we can truly be proud.

Recently, I came to know another relative from my father’s side, my nephew John French and his wife Pam. I only came to meet them after they had seen me on TV. John’s grandmother Madge was my auntie. I saw her a number of times, and I knew her daughter Peggy (my cousin) well when we were both teenagers. John is Peggy’s son and as an engineer worked with a German firm based in Hampshire and has just retired aged 62. He has done a lot of work putting together the family tree and can trace the family back by five generations. It is quite fascinating to see how widespread a quite ordinary family can become.

In the old days, we hardly ever saw each other; you could hardly call our family close-knit. This was before the age of the family car and people simply did not move around as readily as they do today. You would have to go by bus or train (or both) and this could be very tiring and time consuming. Today we think nothing of driving hither and thither. This is one of the major differences in lifestyle from then to now, and it has had a huge effect.

The old Wembley Stadium in north London was built in 1923, three years after I was born in 1920. My elder brother Arnold recalled the open fields and woods which lay between our house and the River Brent before the stadium was built. The area must have become much noisier during the construction of the stadium. We had a small garden behind our house, but it stood immediately onto the street and this would no doubt have become much busier and noisier. As a result, my parents decided to move further out to Sudbury, a suburb of Wembley, 2 or 3 miles further away from central London.

The Wembley area had been largely developed already and Sudbury was the next open area in the north-west. The Piccadilly Underground line had pushed 10 miles or so further out to the west and railway stations were set at key points along the route. Around these, estates were soon built on green fields outside of Sudbury town and Sudbury Hill. New housing was put up and there was steady growth of the metropolis in this direction right up to the start of the Second World War, fifteen years later. The sheer area covered by new housing in this period was phenomenal. This was a familiar pattern as London expanded and people moved further out. The development of the Tube lines encouraged this and fostered the great outward growth of London.

Our father bought a new house at 18 Station Crescent in 1924 and we were to live there for the next twenty years or so. It was close to the Sudbury Town Underground station, three minutes’ walk away, so he was able to easily commute up to the City. Later, I was to use the railway on a daily basis to get to Latymer in Hammersmith for my schooling.

The house itself was of semi-detached design, which was quite the fashion in housing development at that time. Many streets had been built on this pattern: two houses built as one unit with a space between that and the next double unit. I used to wonder why it was developed in this way, but I suppose the design allowed the family to go in through the back door, as well as through the front door. Later, it proved even more useful because in the 1950s and 1960s many people put in a garage to house the family cars which had become so popular after the war.

We had a back garden, but it was always in the shade, cold and unfriendly. The front of the house and garden got all the sun. Our real back garden was Horsenden Hill, an open space six or seven minutes’ walk away from our house. The top of the hill itself was fifteen minutes or so away. This was the only space that remained green in our area. The Grand Junction Canal flowed a further ten minutes away. My younger brother Frank and I used to play in the woods and fields on the lower slopes round Horsenden Hill, with endless games of football and cricket using two trees as goal posts and one tree as the stumps. The hill was very pleasant territory, and if you went over the top and far enough down the other side you would come to the Grand Junction Canal and see horses on the towpath pulling barges behind them. The bargemen on board would give us a wave. At another point, near the top of the hill, the grass had been worn away. There were two or three tea trays that kids like us used to slide down the hill on. Nobody ever walked off with those tea trays – they were part of our heavenly playground on the hill.

Another reminder of the nineteenth-century mode of life was provided by an establishment 50 yards away from our house at that time. This was a smithy run by a full-time blacksmith. There was still a substantial need to shoe horses and to carry out other kinds of metalwork.

It is strange to realise the scope and pace of the changes in London over the last century. In the lifetime of one man, who still remembers the situation, the area we lived in just after the First World War changed enormously.

HOLIDAYS

Every summer our parents would take us children to the seaside for two or three weeks. At first, this meant Bournemouth. In later years, we went to Minehead and Sandown on the Isle of Wight; always where there were sandy beaches. These were greatly enjoyable. We built sandcastles, played ball games on the sand and splashed about in the sea. My father, usually wearing a summer suit in light grey, would smoke either a pipe or cigarettes. However, he never paddled; he was probably worried about showing his legs with the varicose veins. My mother always wore a summer dress or skirt with stockings, which she would never take off in public, so she never paddled either. In those days, people were much more conservative about what they wore on the beach; even men’s swimming costumes usually went up to the chest. Everybody, including children were much more covered up.

We used to go on the kind of excursions common to such places. At Sandown, for instance, we went to Osborne House, and it was there that I started to take an interest in our country houses. My love of these often fine historic houses which survive to this day is now shared by my wife Mei, who has a great interest in the historical side of our country. Indeed, we have both taken great enjoyment when we make trips or even just see them on the television. We both enjoy the countryside and country towns.

LIFE AT HOME

Monday was wash day every week and it was physically an extremely taxing job. My mother had a peaceful, equable nature, but it was as well not to cross her on Mondays! The process began by setting up a copper in the kitchen. This was a large, round tub, about 3ft high and 2½ft across. The clothes were put in and water poured in from kettles – a small amount of cold, but mostly hot. They then had to be stirred around with a ‘dolly stick’ and, of course, they became very heavy as the water soaked into them. When this process had been thoroughly completed, any remaining dirty bits on the clothes were rubbed over with soap (no soap flakes at that time) and thoroughly rinsed. The clothes were then lifted out one by one and rinsed out with fresh cold water from the tap in the sink, then rung out and hung up in the garden. This had to be done for all the clothes that needed washing: shirts, underpants, even bed sheets, tablecloths and so on. Nowadays, wash days are made lighter by throwing everything into the washing machine. This is just one example of how daily labour has been made easier in the home during the last seventy years or so.

After my homework, I used to help my mother from time to time with her work in the kitchen. I also used to help with the shopping sometimes. On Saturdays we liked to have Sainsbury’s sausages for lunch, so I had to walk all the way to the supermarket and buy a pound of sausages for the family. I loved to buy the butter. The counter assistant had a huge slab of butter in front of him and two wooden paddles. With these, he would carve off just the right amount and pat it into shape before wrapping it up. It was fun to watch his wonderful dexterity and speed.

I was usually very happy to make a contribution to help my mother because she had so much to do with the family and three boys. My elder brother Arnold did not pitch in on this; he was usually out and about with his mates. They formed a group which nowadays would probably be called a gang, but they never got involved in vandalising cars or property or any other mischief. I used to see very little of Arnold as he was always off and away.

I saw a lot more of my younger brother Frank. I was very close to him because I looked after him and played with him as he was three and a half years younger than me. We used to sleep in the same bed. I took the initiative in the games that we played before we went to bed. We were supposed to go to sleep at once, but most nights I would make up stories with him and he would play his part in whatever went on, but he had few initiatives – they all came from me! I loved acting things out to make him laugh. It was a good exercise of the imagination. However, sometimes my parents did not agree – they wanted us to go to sleep! When our voices went on too long there would be menacing shouts up the stairs. If we still continued then, instead of my mother, it would be my father shouting up the stairs. That always produced peace and quiet. My parents did not punish us, although they exercised their authority nonetheless and had little trouble with any of us.

On Sunday mornings in the winter, while my parents enjoyed a lie-in, I used to light the sitting room fire using balls of newspaper and sticks bought from the grocer. The other rooms remained unheated. I must have been 8 or 9 years old and Frank 5 or 6. Nowadays we just flick a switch on the central heating, gas fire or electric fire – it’s much easier!

SCHOOLING

My schooling started at age 6. First, it was at Eton College (not quite the public school, but a tiny private school in Eton Avenue, Sudbury, in north-west London). I used to go to and from the school each day by myself, ten minutes each way. I still remember the roads I went through – quite simple and straight – past the Grand Central railway station, where the trains were still pulled along by steam engines; it was fascinating to see.

The school was run by Ms Dutton and I still remember she suffered from mild rhinitis and was always delicately dabbing her nose with a handkerchief. There were roughly thirty girls there and six boys, of which I was one. Amazingly, I was to meet up with one of them, Arthur Hall, when I went to live in a boarding house in Aberystwyth thirteen years later at UCL.

After this short spell at Eton College, when I was 7 my parents moved me to Wembley College, another private school run by headmaster, Mr Topliss. He taught us geography, but nothing else. Most of the rest of our education was down to Mr Fairbairn, the first of a series of really good teachers I was fortunate enough to have. He took most of the other subjects and did a very good job of interesting us in whatever we were learning. Mr Topliss, who normally sported a ginger-coloured suit with plus fours, ran the school but made little contribution to the teaching.

We normally had a fifteen-minute walk to school and then back at the end of the school day. Occasionally, our milkman would kindly give me a lift to the school in his Trojan milk float. This had solid rubber wheels and, as a result, the 400 bottles would make a terrible din, so that when I got off I was quite stupefied. The noise was made worse by the fact that the road had tramlines set in stone bricks.

Wembley College was a modest-looking establishment: a mid-sized suburban house, adapted to make two or three classrooms and educating between sixty and seventy students. Next door was the headmaster’s house, so he could keep regular control of what was happening in the school. I did well at the college and was given substantial encouragement: I won prizes each year. I still have one of these, a book with the arms of the school handsomely embossed on the front in gold. The book itself – Silas Marner by George Eliot – was just about the least appropriate book to give an 11-year-old boy. I haven’t actually managed to read it all, even now, but I am still proud of it.

This kind of encouragement must have helped me realise that it was worthwhile working hard for the future. At any rate, my parents must have been convinced that I was worth backing because they put me up for a scholarship at Latymer Upper School in Hammersmith, west London. If I could win that, it would be a very useful support financially, because I would have a grant to pay the fees which amounted to the princely sum of £6 each term. Fortunately, I did win the scholarship and started at Latymer in 1933.

2

LATYMER UPPER SCHOOL

I gained the scholarship and spent the next six years at Latymer, from 1933 until 1939. I made substantial progress on all subjects. Latymer was a first-class private boys’ school and I had excellent teachers. I still remember with gratitude Mr Gregory, who taught me German and French. I made huge progress in both languages, and this prepared me to take a course in German and French at University College London (UCL) later on.

In comparison to Wembley College, at Latymer classes were a very much more serious affair and there was a relatively strict discipline imposed. In spite of that, the teaching was excellent and enjoyable. We wore a uniform with the school badge on the breast pocket, similar to today. I always enjoyed my studies and I have never been able to understand why so many boys did not react well to teaching and mucked about – it is a mystery to me. We had more subjects to deal with at Latymer School – art, scripture, history and German were added to our curriculum.

There was also a lot more scope on the sport side. I have many memories of the sports ground at Shepherd’s Bush, where Latymer had its own playing fields, and I joined in on the cricket team. It was difficult for me to take part in football because, like my brother Frank, I had a poor chest and would be wheezing heavily after a few minutes. There were no ‘puffers’ (inhalers) in those days to bring relief. Nonetheless, I went on to become the school captain in cricket and did well both as a batsman and a bowler. I remember, in particular, there was an annual match of the first XI boys against a team made up of the teachers, and the boys won! I took part in the match against the teachers, which was always the most interesting event, although if you were bowling you had to be careful not to send down fast snorters to teachers who might then take it out on you when you got back to the classroom!

I continued to do well in my classwork, and when it came to the end of my schooldays I qualified for a place at University College London. UCL is one of the top three universities in the UK and probably the best for modern languages. Before I went to UCL, my mother had a brilliant idea. She arranged for me to spend six weeks in Germany to practise my German. She booked me into a German boarding house in Bad Godesberg, near Cologne. This was a quiet spa town on the River Rhine. There were no English-speakers, which was immensely valuable because I was obliged to speak German all the time with the other people in the house. My ability in the language improved in leaps and bounds.

After two weeks, my mother left me in the safe hands of Frau Becker, a lady of approximately 50 years of age who ran the guest house. There were five or six other guests, including Herr Kaufmann, a retired banking executive of 70 years. I was then 18 and we did not have much common ground. Nonetheless, it was helpful to speak with him. I used to go for walks with him along the Rhine and in the pleasant town. Another guest was a very different cup of tea: a young man of about 25 and one of the typical Nazis who supported Hitler fanatically. He seemed to make the others very uncomfortable with his views, though none of them dared to raise any objections as he would have reported them to the Gestapo and they would have suffered the consequences.

At that time, however, Hitler was doing seemingly extraordinary and praiseworthy things, raising the country by its bootstraps. This was the best period of his rule, in 1938. I was greatly saddened when war was actually declared in 1939, because it seemed such a pointless exercise. In the end, the war finished in 1945 and cost roughly 10 million lives every year – a total of 55 million people died in Europe. That was the price we paid for Hitler’s rule.

However, there was little or no sign of that in 1938 while I was in Germany. Relations were friendly between the English and German people, and I was treated very well by the members of the household and Frau Becker.

When I got back home, I was in good shape to start my degree course at UCL. Thanks to my mother’s initiative and her far sight, after six weeks of German practice I had gained a great deal of confidence. I left London a schoolboy and when I came back I would be a university graduate.