Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

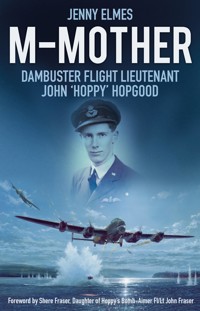

John 'Hoppy' Hopgood, pilot and 2nd in command in the May 1943 Dambusters raid, died a hero at just 21 years old. Wounded by flak and with his Lancaster M-Mother ablaze, Hoppy had no hope of escape yet managed to gain height for two of his crew to parachute to safety. The plane crashed moments later. Using Hoppy's school diary and letters to his mother and sister, this book tells the story of how a boy from a small Surrey village matured into a gutsy war hero. A veteran of forty-eight bombing sorties and an expert pilot in three Bomber Command Squadrons, this is the man who taught Guy Gibson how to fly a Lancaster.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 439

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Acknowledgements

There are many people who have helped me and encouraged me along the way in producing this book: one of my mainstays has been jumbo-jet pilot Andy Bailey, who has helped me unstintingly with technical aviation terms and RAF interpretations. Of course members of my extended family, in particular Annabel Young (Marna’s daughter), James Hopgood (Oliver’s son), and my dear mother Betty Bell (John’s sister) have all been open to my using the family documents and happy to add any memories of their own. Others I wish to acknowledge include: my husband Graham Elmes, Josh Thorpe, John Villers, Keith Fleming, John Newth, Charles Foster, James Holland, Shere Fraser, RAF Scampton, The National Archives at Kew, and RAF Hendon.

M-Mother

Jenny Elmes

The night was so bright that it was possible to see the boys flying on each side quite clearly. On the right was John Hopgood in M-Mother, that grand Englishman whom we called ‘Hoppy’. He was one of the greatest guys in the world. He was devoted to his mother, and devoted to flying; used to go out with us a lot, get drunk – used to go out a lot to Germany, do a wonderful job.

He had no nerves; he loved flying, which he looked upon rather as a highly skilful art, in which one can only become proficient after a lot of experience. He was one of the boys who completely refused to be given a rest, and had done about fifty raids with me in my last squadron.

Perfect at formation was Hoppy too. There he was, his great Lancaster only a few feet from mine, flying perfectly steady, never varying position.

Once when training for this raid we had gone down to Manston in Kent, and had shot up the field with wings inside tail planes, and even the fighter boys had to admit it was the best they had ever seen.

I should say Hoppy was probably the best pilot in the squadron.

Extracted from article in The Sunday Express on 3 December 1944, and reproduced in Enemy Coast Ahead by Wing Commander Guy Gibson, VC DSO DFC, who commanded 617 Squadron in the raid on the Ruhr Dams on the night of 16/17 May 1943.

Flt Lt John V. Hopgood DFC and Bar

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

1 Early Years: A Dambuster is Born

2 M – Marlborough College

3 Family Life Changes as War is Declared

4 The Sky’s the Limit

5 And so to Bomber Command

6 106 Squadron, Together with Wing Commander Guy Gibson

7 Bomber Harris and his Thousand Bomber Raids

8 Per Ardua Ad Astra (Through Adversity, to the Stars)

9 A Special Squadron is Formed

10 ‘Courage Beyond Fear’

11 Après Moi Le Déluge

Postscript

Bibliography

Copyright

Foreword

by Shere Fraser

It is a daunting task to name a child, and yet my parents did not have to toil over their decision and draw from a pool of a thousand names. In fact, it was quite the opposite, and neither my brothers, John Hopgood and Guy, nor I, Shere, could comprehend the significance of those names until much later in life. I remember in childhood hearing my parents say I was named after the beautiful village of Shere, which was a special place, especially for my father. He didn’t talk much about his heroic wartime service, and for us children, we came to know that Daddy was a hero and he helped to stop the war in Europe. For us, he busted dams in Germany, his plane crashed and he then became a prisoner of war for a very long time. Tragically, my father died in a plane crash in 1962 and those memories of his heroic service died with him.

Fast forward fifty years, after a series of life events and what some may call an epiphany, I began a healing journey of getting to know my father through the lens of his wartime letters and experiences. As I opened each new chapter in this journey, I became very grateful for each new revelation. One of the more rewarding experiences was learning about John Hopgood, the man who saved my father on the night of 16/17 May 1943. On that fateful night prior to their departure from Scampton, the crew sensed they might not return, so much so that the navigator, Earnshaw, told my father that they were not coming home. Hopgood’s M-Mother was hit by flak some twenty minutes before the dam was reached and yet he pressed on with a serious head wound and a fervent determination to get the job done. Much has been documented about the Dams Raid, but sadly not much has been written or said about the courage and gallantry of John Hopgood. He was made deputy leader of the attack on the Möhne Dam for a very good reason: Guy Gibson knew the character of this man and entrusted this responsibility fully upon him. Hopgood should have at least got a DSO for his courage and sacrifice, and I feel he should have got the Victoria Cross (VC) posthumously. I know that my father never forgot Hopgood’s act of heroism and demonstrated this by naming his first son after him. My research brought me full circle and I have come to understand now why I was named after the village of Shere. It was in remembrance of the place where ‘Hoppy’ grew up, but in my heart Shere is not just a village. It is a name of honour, where I will uphold John Vere Hopgood’s memory for the rest of my life.

NB The log books of Shere Fraser’s father, John Fraser, bombardier, and Ken Earnshaw, navigator, both crew members of AJ-M, were stolen in 2003. Any help from the public in tracing them would be very much appreciated.

Introduction

John Vere Hopgood died a hero on the night of 16/17 May 1943, a Dambuster, piloting a Lancaster Bomber (AVRO–M) over the Möhne Dam in one of the most iconic bombing missions of the Second World War. This book is drawn on previously unpublished family papers to show how a typical English public school boy and his family responded to the war, particularly through his letters to his mother, Grace, to whom, as Guy Gibson stated, John was devoted.

John’s mother, Grace, was Harold Hopgood’s second wife. Harold’s first wife, Beatrice Walker, had died leaving him with two children, Joan and Oliver Hopgood. Grace and Harold then went on to have three more children, Marna (born June 1920), John (born August 1921) and Elizabeth (Betty), my mother (born December 1923).

John’s mother, Grace, aged 45 years, plus a scrap of letter written by her in later life

Grace Fison’s father, Lewis, was connected to the Fison seed and fertiliser family of Cambridge, but her mother, Jane Bukely De Vere Hunt, was descended from an Earl of Oxford through the Irish De Vere Hunt lineage. This gave Grace a somewhat exaggerated opinion of her social status, and she passed this on to Marna and John along with the De Vere name. There are some examples of this ‘snobbery’ in John’s early letters, and it is a combination of all John’s traits, exemplary or otherwise, which made him the hero he became. It also made him the perfect material to be an officer and possibly Guy Gibson’s closest friend: they shared the same background and attitudes and were both a product of their time.

You will see how John fitted in well with squadron life, partly due to, and partly despite of, the prejudices of his upbringing. John was a team player, and he loved the competitive camaraderie of his crew and squadron. His crews were cosmopolitan and with mixed backgrounds but they instantly became a close-nit group, necessarily totally reliant and trusting of each other in the extreme circumstances they were placed. The loss of some of those who shared the training and execution of Operation Chastise (as the Dams Raid was originally termed) on that fateful night of 16/17 May 1943 was like losing family members.

Without understating John’s undoubted heroism, this book is a ‘warts and all’ account of how he metamorphosed from a young, somewhat over-sensitive boy, through his perfectionism and idealism as a teenager and his rebellious youth, to the selfless hero he became. In the twenty-one short years of his life, John was transformed from a gutless goodie to a daredevil Dambuster.

But M is not just for John’s mother and the AV-M Lancaster he flew on the Dams Raid; there were other significant Ms in his life, namely his sister Marna and Marlborough College. Marna was only fourteen months older than John and very close to him: ‘almost a twin’, as Grace wrote. They were both frightfully competitive; however, whereas John was dynamic and forthright, Marna was practical and domesticated. Their mother, Grace, carefully and proudly kept her letters from Marna (in the Auxiliary Territorial Service, or ATS) and John (in the RAF), and their two styles of writing give a balanced and interesting picture of events at home and in service.

My mother, Betty (their sister Elizabeth), who has contributed much to this book in hindsight of those years, was two and a quarter years younger than John and slightly removed from the real horrors of war; she is somewhat embarrassed by her lack of emotion at the time. She admits to living, for the most part, in a bubble of innocence, content with climbing trees and enjoying her little cat, Susan, and the countryside. Now in her nineties and looking back on that time, reliving it through John and Marna’s letters, she does feel emotional and adds extra insight and flavour to the accounts in this book. Betty muses that the war was a great leveller, seeing the destruction, to a great extent, of the class divisions under which she, John and Marna had grown up.

Attending Marlborough College, John was well educated, particularly in the arts, and he mixed with many of the sons of the British elite. He experienced a comradeship with his peers which would prepare him almost seamlessly for squadron life. At school, John was in the Officers Training Corps (OTC) and enjoyed team sports, where, despite being very rebellious in the sixth form, he learnt discipline and team responsibility. His regimented education, along with his family’s influence, led John to despise anybody with ‘no guts’, adult or young person alike. This was to be highly significant in the outcome of his all too short life. John volunteered for the RAF, wanting a sense of excitement and challenge, and the RAF automatically led him into Bomber Command. Here he would have wanted to complete the task his uncles had valiantly fought for in the trenches of the First World War, and John would have been full of the knowledge and idealism that it was a just war for Britain against the Nazis.

John fully expected that the targets would be, as Neville Chamberlain had promised, ‘purely military objectives’, reinforced by Air Commodore Sir John Slessor’s promise that ‘indiscriminate attack on civilian populations’ would ‘never form part of our policy’. Once on the treadmill of Bomber Command, there was no way out, except to desert and be classed as LMF (Lacking in Moral Fibre), a term widely used in the RAF to incur shame and deter desertion. This route would of course have been absolute anathema to John. It was probably a blessing that John never knew that the Dams Raid cost more than 1,300 lives, many of them civilian.

However, towards the middle of the war it became clear that precision bombing was not precise: only one in three bombs were landing within 5 miles of their target because of the primitive nature of the navigation aids. Chief of the Air Staff, Charles Portal, decided, in order ‘to hasten the end of the war’, to abandon previous principles and order more general bombing of German cities. Portal’s deputy, and soon-to-be chief of Bomber Command, Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, carried out orders enthusiastically and lobbied the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, to increase the size of his bomber force; the Lancaster Bomber was manufactured in large numbers and became ‘Harris’s Shining Sword’. So Bomber Command soon became responsible for the indiscriminate bombing of Cologne and Hamburg, something that after the war must have preyed on the consciences of many who had served in the RAF. John would have been no exception. (It is interesting to note, however, that despite the general change of tactics, John’s 617 Squadron was, even after the Dams Raid, still preserved as a specialist squadron for precision bombing, one of its next major targets being the Tirpitz.)

It seems that Portal made some quite radical decisions whilst in the position of Air Chief Marshal; it was, after all, he who approved Wallis’s bouncing bomb plan. Bomber Harris, along with Ralph Cochrane, Chief of No. 5 Group Bomber Command, despite thinking it a crackpot idea which would sap his Lancaster force, obeyed his superior’s orders and saw that Operation Chastise was carried through with the highest priority and with all the resources it needed. Operation Chastise, now known as the Dams Raid, became the icon of what was Best of British in the Second World War, and luckily for Portal, it justified the risk he had taken in backing it. The breaching of the dams served as a terrific morale boost to the British people: one and all could wholeheartedly celebrate the skill of invention, the cooperation of industry and the heroism of Bomber Command, for a feat untainted by controversy and executed in an extraordinarily short timescale. John just happened to be one of the cogs which enabled its success.

By then, living on borrowed time, John could have been forgotten, like many of the other unsung heroes of the war, but he lost his life in a raid which is now legendary, so his heroism is celebrated by all who have been inspired by ‘The Dambusters’. Through John’s letters and diary we can see how his tough upbringing both at home in Shere, Surrey, and through his schooling, especially his public school, had moulded him, along with his church attendance, sport and a strong independent and competitive nature, into the hero he became in his cruelly truncated yet, in the end, celebrated life. John’s strength of character and professionalism enabled him, when faced with extreme challenges as he was in Bomber Command, to glorify his country and to serve his fellow comrades with extreme courage (‘Courage Beyond Fear’) and selflessness.

The mementoes documented and illustrated in this compilation were saved and treasured by John’s mother, Grace, who was staunchly proud of her son. She must have been aware of all the pieces that would add to this glorious story, because I even found the following snippet written by Grace in her latter years. It was torn from a letter in her hand and stated:

It’s so sad having to throw away letters from long ago which bring back so many memories, & which I could have kept; they would make human interest for posterity (if any) & often throw quite interesting sidelights on manners, customs, financial expenses, etc, etc, of one’s forbears. Of such can good stories be made. It is difficult to find out about the intimate daily life of common folk.

Although Grace Hopgood would never have included herself in the term ‘common folk’, I know she would have been delighted that the letter writings of her beloved son, John Vere Hopgood, and others have been preserved in this book ‘for posterity’.

After Grace’s death in 1968, his sister Marna kept the letters and mementoes, just as proudly, in the original old leather case, which I rescued, with her daughter Annabel’s blessing, from under her bed at the nursing home in Marlborough. Here, sadly, in the last stages of dementia, Marna’s life ended in 2011.

Now, more than seventy years after Operation Chastise, its participants are heralded with more admiration than ever, and the question most frequently asked is ‘Why was John Hopgood never awarded the Victoria Cross?’ And the probable answer: John was killed in the raid considered to be, along with the coincidental North African success, probably the biggest morale boost of the Second World War and even the turning point of the war; Churchill would have felt that to give posthumous awards would be dwelling on the tragic losses and morbidity of the raid and so diminish its glorious effect. In modern times, as a hero deprived of his just deserts, this seems to have only enhanced the image of Flt Lt John V. ‘Hoppy’ Hopgood, DFC and Bar. His family can bask in this adulation, his mother Grace would have been justifiably proud, but John himself has missed it all!

Jenny Elmes, John’s niece, daughter of Elizabeth (Betty) Dorothea Hopgood

1

Early Years: A Dambuster is Born

John Vere Hopgood was born on 29 August 1921 at Dorndon, in the village of Hurst, Berkshire. A robin appeared on the windowsill as John Vere Hopgood emerged from his long struggle to be born, its fiery orange breast an unlucky omen, as the midwife remarked. Was this to be prophetic of his end in the flaming M-Mother?

John was second son to London solicitor Harold Burn Hopgood but first son to Harold’s second wife, Grace (née Fison). This notice appeared in The Times: ‘HOPGOOD, – On Monday, the 29th August 1921, at Dorndon, Hurst, Berks, to GRACE, wife of HAROLD BURN HOPGOOD, of Hurst, and 11, New Square, Lincoln’s Inn – a son.’

John’s youth was spent in the family home Hurstcote in Shere, near Guildford, Surrey. He attended the Lanesborough Prep School in Guildford, followed by Marlborough College, where he was a good all rounder. In March 1939 he qualified as a school member of the junior division of the OTC. He played football and cricket in school teams and also played a good deal of tennis; he enjoyed entering local tournaments during the holidays. Music was his chief hobby: he played the piano and the oboe quite proficiently and was a member of the school orchestra. Natural history and photography also interested him.

His older sister Marna recalled:

As a person, John was sensitive, kind, intelligent and thoughtful. He loved his home and family, but also his independence and was able to divide himself between the two without conflict. He was ambitious to do well in whatever he took up, working hard to get to the top. His sense of humour was such that he was involved in many youthful pranks, but he was sufficiently aware of the law to know when to stop! He would never do anything to hurt anything. I remember how distressed he was when he shot a green woodpecker in mistake for a pigeon, so much so that he had it stuffed and enshrined in a glass case in his room. He never went shooting after that day. One of the reasons that he went into Bomber Command was that he did not wish to see the immediate results of human suffering from the weapons of war. He felt that to be in the clouds would separate him from the awful act of killing. I know this worried him a great deal; he did not want to kill his fellow human beings. John was due to go to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge in 1939, but as war broke out in the autumn, he decided it was not worthwhile starting at university. Until he joined up he spent a few months articled as a Solicitor’s Clerk to a friend of his father’s in the City. He joined the RAF in 1940. John was 21 when he died; he had always given of his best to serve his country. He had known his chance of survival to the end of the war was remote.

His younger sister Betty says John was prone to tears and not a daredevil as a child; he was close and competitive with Marna, who was only fourteen months older. In contrast, Betty loved to climb trees, right to the very top, which she felt Marna and John were too scared to do, and she resented John for trying to shoot her beloved birds and squirrels. Betty enjoyed the company of her little cat, Susan, and felt she was just the silly younger sister. She remembers that, when young, John enjoyed drawing aeroplanes, and, as he matured, would often be found lying on the sitting room floor reading The Times newspaper. He was, however, always caring towards other people, sociable and sporty.

John aged 7 years at Lanesborough Prep School

John’s first school report, aged 5 years, from Lanesborough Preparatory School Kindergarten, near Surrey, said that his ‘diligence and application’ were ‘very good’ and he worked with ‘perseverance’; even at this young age he was good at handwork and writing, and showing aptitude for sport and music. This was to be John’s hallmark in the future when Guy Gibson recommended him for an award reporting that ‘he pressed home his attacks with great determination’.

At the age of 10 years, a weekly boarder, he was already fiercely competitive, and very much enjoyed a challenge, as shown in the extracts from next the letter:

Mother and John, November 1921

John, aged 2 years, with sister Marna

The five Hopgood children, 1926 (l-r Oliver, Joan, Marna, John, Betty)

John aged 6 years

Lanesborough School,

Cranley Rd.,

Guildford,

Surrey

May 1932

My darling Mummy,

I am sorry to disappoint you but I am not moved up but I may be moved up at half-term. If I am first and many marks above the rest I may be moved up at half-term, but do not worry I am moved up into a higher form in Maths and I shall be doing Algebra & Geometry in it and so far I am 2nd already and my same old rival is first who is Dean; he was first in Maths last term and I cannot beat him but I am going to try. I have played two games of cricket and on Saturday I made four runs.

… Last Thursday I went to the baths and I swam my length again, next time I went to swim 2 lengths. Last time I jumped off the side in the deep end, next time I am going to jump off the spring-board and off those steps, will you please tell Marna that and when I see her that I have done these things …

… I am very happy.

Love to everyone from John Hopgood.

John clearly wanted to impress not only his mother but his older sister Marna as well.

He had always been keen on sport; the picture shows him sitting second from left on the bench in the first XI football team in his final year at Lanesborough Preparatory School.

Betty remembers John, aged about 11 years, talking earnestly to their mother as to how he could possibly ever fight in a war and kill people; he would have to be a conscientious objector. Grace replied that, as he grew older, he was bound to change his ideas and perhaps be more able to cope with the things he feared now.

In 1935 John, aged 13 years old, reluctantly went on a French exchange to the Hoepffner family, who lived in the Vosges. His mother had insisted he go and it proved to be a great success. Grace wanted him to be fluent in French and felt it would be good for him. So probably in order to ensure that he went, she arranged for John’s father, Harold (born in 1865 and so too old to be conscripted in the First World War), to take him and show him the Menin Gate memorial and the First World War sites on the way. Grace’s two brothers, Elliot and Harold, had both been in the trenches in the First World War. This certainly had a big impact on John, as he built up his knowledge of, and attitudes towards, war – and how the other half live.

Lanesborough Prep football team (John second from left on bench)

Letter from Lanesborough Prep

John’s passport photo 1935

He wrote the following letter to his two sisters on Sunday, 28 July 1935:

Dear Marna and Elizabeth,

We arrived safely on Tuesday night at Ypres, Ieper or Yper (Flemish). On the Boat-train from Victoria to Dover we saw a lot of Hops and Kentish Orchards.

It was a smooth crossing yet a lady was sea sick just after we started. We had lunch on board. At Ostende we had tea and then caught a train to Ypres. We travelled 3rd class and when we got in a carriage there was an old Flemish peasant woman who, when we looked at her, took off her shoes, poof! Then she started to eat some bread, 1” thick, with some meat. When the train started she made a cross on her body and murmured a prayer. After a while she took off her stockings, pooh! Her feet were absolutely black; when she last washed I haven’t any idea. At last, to our relief, the ticket collector came round and he swore at her and she kindly obliged by putting on her shoes.

In the train we saw some oats, corn, wheat, flax, tobacco plants, potatoes and cabbages, the whole way, in large quantities. After supper in the Hotel Regina, we went along to the Menin Gate and saw the names of dead soldiers on large stones inside. We also heard the Last Post at 9 o’clock (21 o’clock in European time). They play it every night there and also in the morning. (N! I found out afterwards that they only play it at night).

On Wednesday morning we went in a car which took us round the battle fields and cemeteries of the Great War. We saw Hill 62 and Hill 60. And on both, more so on Hill 62, we saw the Trenches and Dug outs, also the Helmets, Guns, pistols, and various shells which were used in the Great War. I don’t know. In a book on Belgium it said that they (Trenches) were so full of water that the English and the Allies had to build parapets in water and also get under cover. Besides trenches we were able to see shell holes and broken trees and other G.W.R. (Great War Relics). I took some photos. Oh! I forgot on Hill 60 we went in an underground trench. It was wet on foot and very damp and it would have been very dark had it not been that there were electric lights there. It was made, or constructed, rather, of wood and occasionally steel girders to keep up the earth. Also when they first found it, they discovered a soldier’s body lying on a bed, which they think was the hospital ward.

Your brother John.

What an extreme impact the realities and sordidness of trench life must have had on the impressionable John; no wonder he would decide to opt for the RAF and the air.

At home in Shere, in the early days of Hurstcote before money became short, the Hopgoods were very sociable, attending and hosting dinners and dances with others of their social class. They had servants in these early days who would have referred to the children as ‘Miss Marna’, ‘Master John’ and ‘Miss Elizabeth’. However, the Hopgood family lost their wealth in the Great Depression of 1929 and soon only the gardener was left. Hurstcote was turned into flats, and a smaller house, Southridge, was built on the land. The children mucked in to cover the practical duties needed to keep the estate running. Their mother, Grace, started a poultry business and lodged in guest houses whilst building works were under way; their father, Harold, often stayed in London near his law firm.

John continued to practise the piano daily and often played Bridge with his mother. The family attended church regularly and were upright members of the community. John wrote in his diary, aged 16 years:

JAN 2 SUN 1938: As usual we went to church at Shere. … The address was outstandingly good. The theme was that the greatest gift of God to mankind was the inability to foresee the future, and that to face the future we need God and so we must push forth into the New Year with God.

JAN 9 SUN 1938: … In the evening we listened to the service from St Martins-in-the-Field. The theme was that we must not live in the past, but forgive and so build up love. If only the Nations could have forgiven each other at Versailles there would be unthreatened Peace now.

John’s diary pages

John seems to have taken the subjects of sermons very seriously, and this would have moulded his moral attitudes and given him a sense of duty to God and his country.

Enjoying a love of fresh air, wildlife and the countryside, John played golf and cycled miles. The Hopgoods took part in traditional country sports, including beagling and hare-coursing; the poor hare’s head was often saved, stuffed and preserved, and they had some mounted on their walls at Hurstcote.

A hare trophy mounted on the wall

Summer 1938 at Hurstcote (l-r cousin Laurence (later killed in a tank at just 18 years), Betty, John, Marna)

John, Betty and Marna making the most of the snow, Christmas 1938

2

M – Marlborough College

Despite money constraints, John spent his school life, from the age of 14 to 18, in Marlborough College, Wiltshire, following his mother’s family tradition. John’s name appears in the Book of Remembrance, along with his cousin Wilfred Fison’s, and on the Roll of Honour in the chapel at Marlborough College.

Marlborough College always had a rough and rustic character among public schools, and the accepted amount of institutionalised bullying, which fits in with his mother’s idea of bringing up her children to be tough. Marlborough College undertook to give bursaries to all sons of Old Marlburians who had been killed in the First World War, and so there would have been a strong ethos of respect for soldiers and officers.

Whilst John was at Marlborough he overlapped with David Maltby (Marlborough College from 1934–36) for a year. David Maltby was also to become a pilot and take part in Operation Chastise; in fact, it is the bomb from Maltby’s plane AJ-J that puts the finishing touches to breaching the Möhne Dam. Interestingly also, it is David Maltby who signs the last page in John’s Log Book (see end of chapter 9). David was to survive Operation Chastise only to be killed four months later piloting a Lancaster during an aborted operation to the Dortmund–Ems canal.

John started Marlborough College conscientious, competitive and desperate to make the most of his opportunities to please and impress his mother and family; he was also thoughtful and literate, coming top of the class in his first Michaelmas term. You will see in the summary below that John also came first and won the form prize in the summer term of 1938, when Jennings, whom he admired, was his tutor. However, by the time he left Marlborough College he had become a pretty rebellious pupil altogether, and he conspired to be bottom of the class when Wylie, whom he did not like, was his tutor (see John’s diary entry for Monday, 19 December 1938).

(Historically Marlborough College had had many rebels. In 1851 the pupils had caused a riot and the headmaster had fled.)

John at Marlborough College, 1936

Detail from Marlborough College Book of Remembrance

John Vere HOPGOOD’s record at Marlborough College:

Son of H.B. Hopgood Born: 20 August 1921

At Marlborough College from Sept 1935 until July 1939

Term

Form

Form Master

Position in Form

House

Housemaster

Mich. 1935

U.4c

A.R.Pepin*

1st/63 won Form Prize

A House

W.I.Cheeseman

Lent 1936

Shell d

E.C.Marchant

46/98

A House

W.I.Cheeseman

Summer ’36

Shell d

E.C.Marchant

6th/115

A House

W.I.Cheeseman

Mich. 1936

Hundred a

A.E. Spreckley

80/90

C1

L.F.R. Audemars

Lent 1937

Hundred a

A.E. Spreckley

46/98

C1

L.F.R. Audemars

Summer ’37

Hundred a

A.E. Spreckley

6th/115

C1

L.F.R. Audemars

Mich. 1937

Modern 5b

R.A.U. Jennings

13/27

C1

L.F.R. Audemars

Lent 1938

Modern 5b

R.A.U. Jennings

12/26

C1

L.F.R. Audemars

Summer ’38

Modern 5b

R.A.U. Jennings

1st/24 won Form Prize

C

L.F.R. Audemars

Mich. 1938

History U5a

H.Wylie

17/17

C1

L.F.R. Audemars

Lent 1939

History U5a

H.Wylie

14/15

C1

L.F.R. Audemars

Summer ’39

History U5a

H.Wylie

11/14

C1

L.F.R. Audemars

Joined the O.T.C. Sept 1936 Passed Cert A. Part II on 7th March 1939

* His first form master, A.R. Pepin, was a very enthusiastic member of the Signals Section of the College OTC, and it was his pioneering work on radio between the wars which resulted in the development of the basic army walkie-talkie radio set used in the Second World War.

C1 House, Marlborough College

There are few letters surviving from his first years at Marlborough, but they were always respectful to his parents and well written. Here John was just 15 years old and on the main campus in C1 House:

C.1 House

The College

Marlborough

Wilts

18.10.36

My darling Mummy & Daddy,

Thank you so much for the letter …

So glad to hear you can all come on the Sunday. Confirmaga is A.M. at 11 o’clock (BE V. PUNCTUAL), come at 10.45.1*

I played for house 3rd on Thursday but we lost; ahem! I’d rather not say thecrickettotal against us!! But as a result I was put on to top game yesterday, but it was too hard to play. House teams are:– Upper, Lower, 3rd, Remnants. I might play for Lower next time.

I did some more Vol. shooting and did a group of 4 in a halfpenny easily.2**

I am getting to know the Oboe better now and can play afewscales. I might be able to take my piano exam by about half term as I am practising very hard and know the stuff pretty well now.

… A boy has just returned with a rabbit which he saw being killed by a stoat. We don’t know what to do with it, whether to ‘paunch’ it and sell it ‘down’ town, or to see if the cook will prepare it for him to eat, or What?

On Wednesday we were allowed to try and command our section. I volunteered and was quite efficient, except that I let them get out of hearing once and they rather fell to pieces. On Friday we were allowed rifles and have begun to learn rifle drill.

On Tuesday there was a school match against Bath which we lost I think. And yesterday the school played ‘Harlequins A’ and won 16–0.

This morning the preacher was of Blundell’s School.

As an English book this term we are doing Hamlet. I think it’s quite one of Shakespeare’s best. We always have to do a ‘set’ book for the ‘cert’, and this is what the school has chosen.

I think that exhausts the news for the week.

Much love to all,

Your very loving Son.

Note in the next letter that John was beginning to take interest in the opposite sex.

C.1 HOUSE

THE COLLEGE

MARLBOROUGH

11.37

My dearest Mummy and Daddy,

You will doubtless be pleased to hear that I have passed my music exam with 120 out of 150. 120 is the prize mark, so I am lucky enough to get a prize! Lucky!

… Did you see that my friend Dart’s father has been having a row with the Duke of Windsor over the Armistice Celebrations in Paris. Dart’s father is the chief English Dean in Paris and he, as most clergy, is anti the Duke of Windsor.

Confirmation Sunday today. There was no-one whom you know being confirmed but I went to the service (and in order to get a decent pew in the balcony, sneaked in 35 minutes before the service was due to start and learnt my repetition prep! And also dodging the wary eye of the school porter who was attending to the benches; there were a few others also). I met Mrs Ramsden, & Mr & Jill, outside the Chapel, and she told me about the wives fellowship Dance or something next hols (meanwhile I was expecting to be asked out!), but I tactfully withdrew. I was later accosted by many boys to know who the pretty girl was, I was talking with!!! (and was it my sister!)

As we only read one chapter of Gibbon3* a week we have not got much further than halfway (Vol. 1). We had to write an essay on the Constitution of Upper School in the style of Gibbon, and unfortunately the master in charge read mine, and I had written the most licentious and treasonable things about him4** and how his inward fear and trepidation was severely veiled over by a mask of authority, etc etc!!! (My essay was appreciated by Mr Jennings).

Last Sunday we heard a most boring lecture on Alchemy and Alchemists. I learnt practically nix, and certainly could have spent my time more profitably.

I really must stop now and write to Marna.

With much love,

From your very loving Son.

Thus it seems that Marlborough boys were not protected from controversial writings, so not encouraged to conform. John must have taken this on board and, as shown in his diary entries, had his own opinions!

The letter above also illustrates the calibre of his peers and their parents’ attitudes to authority and those in high places. No wonder John came across as arrogant at times. Maybe it was this type of situation – along with his changing hormones – which began to mark a significant change in John’s hereto compliant nature.

John kept a detailed diary from January 1938, in which, as well as noting his school curriculum, officer training and friendships, he refers to war rumblings in the country’s politics and speakers who had impressed him, moulding many of his attitudes:

FEB 2 WED:

Long Parade – I changed quickly and obtained a shine to the brass of my belt. On Parade we did the usual boring arms drill, and a few field signals.

MAR 2 WED:

I am now determined to try and strengthen my personality and not always do what everybody else does – I want to be a captain one day. Chapel was at 11.15, and 3rd period was excused. As I really can’t see any reason to give up something in Lent, and as it would do me no good, for, at the moment, my Christian principles are not strong, I shall not give up anything for Lent. … After lunch we paraded in flannels. Knight is far too beyond himself and is far too bloody officious. We just did the ordinary arms drill, and section leading.

MAR 3 THURS:

In Jenning’s double period we had a long discussion on Socialism and the state, and the probabilities of another war. According to Jennings the state which had the most necessary food stuffs would win in the end, but he heartily advised us not to think of war, and not be too keen to sample it, as each generation always has done.

MAR 7 MONDAY:

In Mole’s period I drew faces, as it was so dull. Double Jennings was more interesting. He gave us back some papers and we discussed the History Chapter and the troubles in the Balkans, which led up to the Great War. … I had a long fight (friendly) with Hope, in which he was victorious.5*

MAR 9 WED:

In Economics, Jennings preached an interesting lecture on atrocity stories. We all recalled various Daily Mirror extracts, such as child slaughter in the ensuing Chino-Japanese War, and also Spanish Civil War. It seems extraordinary – all these wars and rumours of wars. Austria is to have a public vote for Pacifism or not, whilst we are arming to our teeth and Mr Eden has just resigned, with semi welcome and opposition. Who knows but there may be a World War soon and we shall be drawn into it on account of our trade and colonies, although we English people don’t really want to fight!! … After lunch we paraded as House Platoon and were completely lousy and inefficient, chiefly owing to the inefficiency of Phillbrick – Platoon Commander. After Parade until work I practised the Piano.

MAR 12 SAT:

O.M. Club Day – and what a lot of O.M.s! All chattering about ‘When I was here’, and ‘So you remember’, etc etc. I saw the Coxons and Hugh Pothecary, also Robert and Wilfred Fison.6* It was quite a nice sort of day. With Jennings we first of all discussed the History, then he told us and explained the present day situation in Austria (Hitler invaded Austria and is in Vienna), and then we read on in our History Books, and made notes. I greened my belt at night [for camouflage].

MAR 16 WED:

After lunch I stayed in Classroom and read the papers – it is interesting now that Hitler has invaded Austria and practically annexed it. Poor France hates it all, but I think it’s a damn good show; but of course, one never knows where Hitler may go next. I think it will be Romania, as she must have oil and petrol for her army. We had a long discussion in classroom about it.

MAR 17 THURS:

We read on in our History books, and finished it. It was rather interesting, as it dealt with the present day situations up to 1932. Of course it was not accurate – Austria is German now!

MAR 18 FRI:

After lunch I filled my pockets with chocolate, etc for theField Dayand then slowly donned my uniform. Of all the bloody Field Days this was about the bloodiest. Without any exaggeration, lies or misstatements, I did not even see the enemy until 3 mins before the bugle blew for time! We were reserves, and just followed on miles behind everybody. We went over the golf course and down into the Ogg Valley, and finished up about 250 yards from the enemy, behind a ridge on the other side of the valley. The march back was also rotten, as we were right at the very back, could not hear the band, and found it very hard to keep step! Tired and weary with doing nothing, I had a foul lot of Prometheus to do … write a précis as well.

The photograph below shows Marlborough College OTC marching back after a Field Day. Marlborough College continues to train pupils for the military, but it is now a Combined Cadet Force, and the updated sign adorns the building where they currently train.

MAR 23 WED:

Field Day: We advanced for 2½ miles over the Downs (with no shade) and then had lunch.

John described in his diary: ‘An aeroplane gave a demonstration, 150 yards in front of us, in picking up a message 9ft off the ground at high speed; each time it only just cleared the 35ft trees above us – a menace.’ But John explained this in different terms in a letter to his parents, written that very same day:

Marlborough College OTC marching back from Field Day

While we were having our lunch (bare-chested), one of the aeroplanes gave a demonstration in picking up a message off the ground at high speed, without landing. They put up two posts with a line, and message tied on across the middle. This was about 150 yds (no exaggeration) from where we were under some trees, about 20–30ft high. The aeroplane then swooped down, and by sticking out a short stick from its undercarriage managed to pick up the message, with its wheels about 9 ft off the ground! And in 150 yds it managed to just scrape the trees each time! It was really thrilling.

So, if John thought this was thrilling, it is poignant that his last mission in M-Mother should also have involved very low flying and coming back to Scampton with bits of tree caught under their Lancaster.

John had become a pretty normal teenager, with a typically teenage sense of humour:

MAY 2 MON:

God! How damnable – work. The only amusing incident this morning was when someone was asked the p.p. [past participle] of scrire – answer: ‘scru’. Ha, ha! After lunch I went down town and then had a music lesson; there is a new man taking Ferry’s place, who is ill with scarlet fever – he is no good and I hope Ferry comes back soon. I am going to learn Beethoven’s 1st Sonata.

A letter home, dated 12 June 1938, came when John, aged nearly 17, was at an academic peak, having won the form prize by coming top; it also showed a serious bent towards deep, logical and practical thinking:

My dearest Mummy and Daddy,

Thank you for your long letter. I hope you have good weather, and enjoy yourselves. About Prize Day: will you please tell me exactly how many you will be for Prize Day,as soon as possible(because of getting tickets). I hope Jane [Marna’s friend whom he likes] will be able to come; and she wants to know, sort of thing, because she is holding another invitation open. Is Joan [John’s half-sister] coming etc etc. We can squeeze 5 in for the concert (it’s easy to gate-crash, if I haven’t got enough tickets, and they can’t refuse to let you in, but I can get 4 tickets for certain, and probably 4 for Prize Giving).

I haven’t played any cricket this week, except one net. Otherwise I have watched cricket or bicycled.

On Thursday, Mr Dalton, the ex-under-secretary for Foreign Affairs (in the last Labour Government) spoke to us and said:– that to prevent London, or other such large towns, spreading, and spending millions on improving roads etc to accommodate for the great population, it would be better to make new towns! His idea was to take a factory from London with its dependent population (or workers), and plant it and them down in some village or town in the country, so that all the people who came into London to get work, would have to go into these new towns! (He seems to forget that this is free England, not communistic Russia!) I asked thousands of questions & really pestered him. I could not see why to make say 6 new towns, with new roads and better railways to them, should be less expensive than improving the roads round London. I also asked him if he realised what was going to become of the country, with all these new roads and increased traffic on them from new town to new town etc. I also suggested an agricultural slump 75 years ahead7* since farm labourers would desert the land, to work in the nearby factories where they would get a better wage, better securities for living, and an easier job. He said that mechanism would rectify that, to which I replied that since a mechanical machine quickened the process of harvest (for example) it was therefore able to farm greater extents of land, and to make this mechanism worthwhile, larger areas were required, but since his factories and new towns and roads could spread all over the country, it did not look as though mechanism would really be much help, since the farms would remain small, and become smaller and so many labourers would still be required for each farm. He was quite pleased with my questions, and said there was no satisfactory answer at present to the agricultural problems. He confessed ignorance of agriculture – I wish he would just consider the farmer’s point of view before he puts his artificial towns down! I enjoyed it very much and we kept him talking, getting keener and keener until we were stopped at nearly ½ past 10 …

Looking forward to seeing as many of you as possible on Prize Day (also hoping to hear soon how many).

Much love to all,

From your loving Son.

What an active mind and sensible ideas he had, and how he liked a good debate! John was certainly a strong and resolute character, and, although we do not know how fate would have served him if there had not been a Second World War, the RAF seemed to provide just the challenge he needed. Yet what a waste the war proved to be when young men such as John were killed in their thousands.

JUNE 18 SAT:

Marna’s birthday (18) send large present.

Note in the entry above just how John dotes on his closest sister.

John was still very much involved with the OTC and military training, and he wrote this letter from the school’s OTC military Camp on 31 July 1938:

My dearest Mummy and Daddy,

Here I am, sitting in glorious sunshine, with only shorts on. As far as I can gather we never do get bad weather at Camp! Thanks very much for all your letters. I can’t let you know exactly what time I can get home, for I have to go by train the army tells me and they won’t tell me yet! As I live near I shall have to help clear up so I probably shan’t get off until about 11, getting home in time for lunch. In which case you won’t be able to meet me, so I will get home independently.

I am enjoying Camp immensely. From 3.30 until 10.15 we can do anything we like – the gritty part of the day is in the morning. Up punctually at 6.30, clean uniform & equipment; make piles, clean out tent; breakfast and then parade. Army prayers are very funny, and most of Marlborough accompany the padre in a special military prayer, and also his speech on where the H.C. [Holy Communion] tent is. After prayers and a spot of drilling by a major Catt (‘pussy’) with lovely whiskers who talks too much; and then we go for a march to a place about 2–3 miles away, watch a demonstration by the Grenadier or Scots Guards, and do about an hour’s ‘field day’ and then go back for a 1.30 or 2 o’clock lunch. We get on our paillasses at about 10.15 pm.

Last night we went on night operations, which were awfully good fun. But it was a bit of a strive having to get up at 7 this morning, and getting everything done extra well and half an hour earlier for church parade, after being up until 2 last night.

By the way, Wilkie Rowe has invited me for a week on the Broads, Sept 7th – 12th or 13th, and I am wriring to accept. I hope that is OK I shall probably have to come back on the 12th as Lanesborough Old Boys match is then.

Please convey my heartiest congratulations to Marna on the Driving Test. Am also very sorry to hear about breaking up of Birtley House [Betty’s Private School that she loved so much]. Will tell you all about Camp when I see you,

With much love,

Your loving Son.

John certainly learnt to understand military discipline from these camps, which would serve him well in the future.

Although we have nothing in John’s diary for the rest of September and the whole of October, we do have some letters. One to his parents is dated 25 September 1938 and describes a glimpse of Queen Mary, but more importantly, it indicates that there are now even more serious concerns that war might be imminent; it is written from C1 Marlborough:

On Friday Queen Mary drove through Marlborough. Being a 6th form I lined the road. She came through ½ an hour late – so we missed the whole period. I had a good view from some railings.

… I should get as much holiday as you can!! No one here is very optimistic – I for one am not, and I think it will be a good thing if the English army hurries up and mobilises, and not be left in the lurch by other nations.

At this same time, his sister Betty was beginning to worry about war. She says, ‘The possibility of imminent war was played down by the authorities. Nevertheless we picked up frightening vibes and I had nightmares at night!’ Grace, her mother, must have been alerted to her worries by her letters and tried to reassure her in a reply:

Don’t be alarmed at all thisWarTalk – Thank Goodness the authoritiesarebustling about & taking all precautions – But jut keep calm & pray that the forces of Charity and reason will prevail – Hitler has invited Mussolini, Chamberlain, the French and Czech prime ministers – to have a talk with him – and it looks as if Hitlerdoesrealise that the whole world would be shocked unless hedoeshave the matter arranged bytalkinstead of byfighting. Unfortunately the Germanpeopleas a whole have not been allowed to hear what America, England etc are trying to do for Peace.8*

John’s letter of 2 October perhaps provided his parents with a brief respite from the worries of war:

My dear Mummy and Daddy,

Well, I think we may safely breathe again.

On Thursday, the College at last threw a panic and Pont9*