Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

This is the remarkable journal of an Englishwoman in her early thirties abroad in Ireland, recently widowed and sole mistress of the vast neo-medieval Castle Freke overlooking a remote headland in west Cork, where she raised her young family in the company of servants, dependants and occasional visitors. Reflective and sensitive, Mary Carbery was deeply attuned to the spirit of place and to the people she lived amongst in Ross Carbery, studying Irish and taking note of local speech, folklife and customs. This journal of 1898 to 1901, previously unpublished, is an intimate record of one woman's growing attachment to an alien countryside and its inhabitants, bringing them vividly to life with the eye of a naturalist and the ear of a writer. The editor, Jeremy Sandford, describes his grandmother's life before and after the period of journal, and the fate of the Carbery family at a time of seismic political and social change. His commentary encompasses the terrible fire of 1910, and the rebuilding of the castle; the disaffection of her eldest son John, and 10th Lord Carbery – a daredevil aeronaut who sold Castle Freke in 1919 and joined the 'Happy Valley' set in Kenya; and Mary's own wanderings, writings and gentle decline at Eye Manor in the Welsh border country. A singular work, appearing in the centenary year of its inception, Mary Carbery's West Cork Journal will take its place among the minor classics of Ireland's Literary Revival.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 290

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1998

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MARY CARBERY’S WEST CORK JOURNAL

1898–1901

or

“From the Back of Beyond”

EDITED BY JEREMY SANDFORD

CONTENTS

Title Page

List of Illustrations

Introduction

The People of Castle Freke

Spring

Summer

Autumn

Winter

Epilogue: The Carbery Family after 1901

Appendix: Sale Particulars of Castle Freke, July 24th, 1919

Plates

Copyright

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

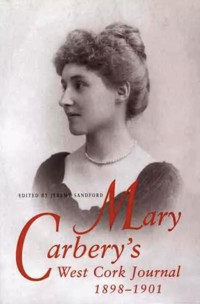

Mary Carbery

Exterior view of Castle Freke with staff (courtesy Fachtna O’Callaghan)

The dining-room, Castle Freke

Con Brien

Ned Good

Jerry Spillane, Leary and Paddy Regan

Shannon’s portrait of Mary, John and Ralfe

Dr Arthur (“Kit”) Sandford

John, 10th Lord Carbery

Christopher Sandford

INTRODUCTION

WHEN MY GRANDMOTHER, as a young woman over a hundred years ago, married Algernon, the 9th Lord Carbery, he took her to his neo-medieval castle on the south-west seaboard of County Cork.

His family claimed descent from Elystan Glodrydd, Prince of Fferlys, and the name of the castle was Castle Freke. Mary Carbery went out to West Cork from England unsuspecting that she would be so overwhelmed by its beauty. But at once she fell for it entirely.

Of her first days and her great happiness there she has left little record. But as a boy I used to sit with her at my parents’ home while she described the early days to me. She used to say that since she had left the castle she’d been a wanderer all her life. She consoled herself in her latter days by writing books. But her heart rested still in the past. Although it wasn’t until much later that I learnt the whole story, even then, in my mind, a fairytale quality attached itself to the castle.

Grandmother’s happiness was short-lived. A few years after their marriage Algernon began to sicken with consumption. Within a painfully short time he was dead. My grandmother, then in her early thirties, was left as sole mistress of this many-towered place on its hilly promontory above Ounahincha Bay, and of its many acres of woodland, moor and marsh, and of the “holy” lake of Kilkerran. Offshore the sea was studded with the islands, mostly desolate but some inhabited, still known as “Carbery’s Hundred Islands”.

A few years back I visited Castle Freke, and I found it every bit as marvellous as she’d described it. Here was the little market town of Ross Carbery, with its brightly painted houses, many of them pubs, and the grey streets that seemed too wide for them. Here was the sea tearing at the Long Strand, with the tall Atlantic waters breaking over it in foam, here the mantling woods, the sandhills and the bogs, the long drive skirting the grey marsh. And then, amidst deep woods, on a sudden eminence, with its Wagnerian terraces falling from it southward and westward towards the sea, and its many towers standing up against the sky, the castle, more beautiful than anything I could have dreamed.

As I drew nearer I saw that the face of the castle was blank, its towers shattered, and its windows empty. But this did not diminish its grandeur. Still it stood up, as romantic a sight as I had ever seen.

At the West Lodge I found someone waiting for me. It was a resident of the village, whose father had worked for my grandmother, and who himself later became steward of the ruined estate.

Knocked – knocked – ah sir, all knocked. I’ll tell YOU now, if ’twas up today, wouldn’t be allowed to do it. Ah sir, and now if you walk with me yonder, you can see it. There sir stood the castle. And there were the doors of cedar and pillars all of marble. I’ll tell you now. Yonder the bedroom of her Ladyship, and there the boudoir with the great view of the ocean. And from here you can see well nigh all the Carbery lands and demesne, the bog and the woodland, and pasture, all knocked now, all gone back.

She was far younger than you sir when she was mistress of it all. And here after her Lord had died she lived alone … I have heard that her family desired her to return to England. But she did not leave.

What were the feelings of this young woman in her castle amidst the bogs and woodland, with her husband’s ashes buried beneath the headland where she was to erect a huge cross by the sea? From other villagers I heard other stories; how she would ride endlessly the empty countryside. I thought I could fancy something of her strange solitude. Later, in the attic of Eye Manor in Herefordshire, Mary Carbery’s final home, I unexpectedly came upon her journal.

MARY CARBERY was not the first woman to write of the joys and tribulations of running that ill-fated estate. In the seventeenth century, then called Rathbarry, it had formed much of the backdrop for the diaries of Elizabeth Freke (1641–1714), sub-titled “Some Few Remembrances of my Misfortuns which have attended me in my unhappy life since I were marryed: whc was November the 14, 1671”; the diaries were edited by Mary and published in Cork in 1913. Freke, later Evans-Freke, was the family name of the Carberys. Elizabeth was another young Englishwoman, who came out as an Irishman’s bride in 1676, returning eventually in 1696; Rathbarry Castle had been bought by Captain Arthur Freke, her uncle, from Lord Barrymore, son-in-law of Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork, who had “founded” Clonakilty in 1605 and settled it with a hundred Protestant English families.

Other writers too have celebrated this beautiful area of West Cork and have acquainted us with that lost world in which, as Gifford Lewis writes in her introduction to TheSelectedLettersofSomervilleandRoss, “it is eventually borne in upon the reader that in the Anglo-Irish ‘ascendancy’ of the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth was an enormous confidence trick, shored up by faithful servants and good horsemanship”.

“Let us take Carbery and grind its bones to make our bread,” wrote Edith Somerville, Mary’s well-known literary neighbour, to Violet Martin, a.k.a. Martin Ross. The administrative district of Carbery formed the location for SomeExperiencesofanIrishR.M. and other works of Somerville and Ross. Drishane, Edith Somerville’s family home, was in Castletownshend, a few miles up the coast. She rode with the West Carbery Hunt. One letter tells how her sister, Hildegarde Somerville, went to a dance at Castle Freke in July 1905 and

arrived … this morning at 6.30. She then went to bed … She says it was an excellent dance. Crowds of surplus men, perfect floor, band, supper, champagne – Lady C. had ordered an army of assistant hireling waiters from Cork, & every man of them arrived blind drunk & had to be put to bed instantly! However all went well. H.’s young charges, from Edie Whitla to Loo Loo, got on first rate & had all the dancing they wanted, & H. herself said that it was very good fun. There were some very wild Easterns there – Nevill Penrose heard a man say to the girl of his heart “Blasht yer soul, where were ye hiding that I couldn’t find ye!” But all the decent people were there too; the incredibly kind Mrs Guinness had lent Bock a most lovely dress. Handpaintedchiffon and silver spangles, H. says it must have cost about 20 guineas.

Mary’s journal, hitherto unpublished, gives further glimpses into this world when most of these people had little inkling that, within very few years, much of Ireland would be independent of England; or that Castle Freke estate and the employment of the many people who worked there would so soon be a thing of the past.

“IF QUEEN VICTORIA can learn Hindustani then I can learn Irish,” Mary wrote. She became entranced by the customs and history of Ireland.

She had been born in England in 1867 into the Toulmin family who lived in Childwickbury, between St Albans and Harpenden, and later at The Pré, near St Albans. She describes life up to the age of seventeen in her book HappyWorld, started when she was twelve but not finished until she was living in a cottage at my father’s home in 1941. Her grandfather had made a small fortune with his fleet of merchant ships. Her father preferred a life of worthy leisure with his wife and many children in the country.

Mary’s childhood included visits to local poor or sick, and to prisoners in St Albans Gaol. At one point in she falls sick and apparently nearly dies. “‘You were unconscious, to the world,’ her mother says. ‘You seemed very happy. Now and then you tried to beat time with your hand. I thought you were dying. I thought you were listening to angelic music …’” This experience led Mary to wonder if she had a musical talent. Her sister Connie in her book HappyMemories, describes how she “attended the Royal Academy of Music in London, and later won the silver medal…. At St Albans she helped to found the School of Music, and took a great interest in the Abbey choir-boys, to one of whom she gave piano lessons in The Pré and he went on to become a great organist.”

At the end of HappyWorld Mary appears to be a little in love with her cousin, Hugh Beaufort. At a garden party he asks her, “‘I suppose you’re too old to come up a tree for a talk? You couldn’t in that frock? What a pity! I want to ask you something. Mary …’

‘You’re wanted, sir, to make up a set,’ said the butler, and off Hugh went, full tilt, with a cloud on his usually sunny face.”

Her sister Connie wrote, “I have heard it said she was ‘the most beautiful girl in Hertfordshire’.” In 1890, at a May Ball in Cambridge, Mary met the man who was to be her husband. In November of that year they were married.

Mary and Algy passed through Folkestone on their honeymoon and later lived for a period in a villa at El Bior, above Algiers, where the climate was thought to be better for Algy’s already failing health. At that time, so we learn from a reminiscence in Mary’s journal, she was expecting her first baby. This was John, born in 1892.

In 1897 her second son, Ralfe, was born. Algy was by now very ill. In the journal we encounter a memory of him at this time, lying in a tent, possibly a small open-sided marquee, on the lawn.

Algy died in the Imperial Hotel in the Malvern Hills in England in 1898, having travelled there in the belief that the climate there might secure him a few more weeks of life. The six-year-old John (“Jacky”) became the new Lord Carbery. Mary was to be mistress of the castle and estate until John came of age. This is the point at which her journal begins.

THE PEOPLE OF CASTLE FREKE

IntheHouse

Mary, Lady Carbery (aet. 30–33); John (“Jacky”), Lord Carbery (aet. 6–9); “Baby”, Ralfe Evans-Freke (aet. 1–3); Miss Singer, nanny; Miss D., governess; Mr H. Perry-Ayscough, tutor; Taylor, Scottish maid; Court, housekeeper; Ellen, Alice, Annie, Nancy, Julia, and other maids; Amy, nursery maid; Carmody, butler; Mrs Carmody and Alice in the West Lodge; Thomas Ward and Charles de Courcy, footmen; Ned Good, odd man.

IntheGarden

Jenkins, head gardener; Mrs Jenkins and Victor and Dennis, little boys; Hayes; Paddy Regan; Robert Brien, an old soldier known as “her ladyship’s own gardening man”; Jerry Spillane; Mr and Mrs Duggan.

IntheStables

Nobbs, a young English coachman; James McCarthy, groom; Jerome and Jack, his brothers, helpers; Con Brien, helper, later chauffeur.

Keeper

Hay, Mrs Hay, and children.

OntheFarm

Mr M. and Mr Duthie, successive stewards; Gaucher, cowman; Curly Collins, carter; Mike Madden, labourer; Mrs Leary, a lunatic; Leary; Hawkins and Mrs Hawkins, lodge-keepers (parents of Alice and Annie); Con Brien, watcher of the strand; three roadmen, including Paddy Spillane; old Mike; Mrs Leary, fisherwoman; Johnny Sweeney, fisherman; Costello, carpenter.

SPRING

Sinostrevieestmoinsqu’unejournée

Enl’éternel,sil’anquifaictletour

Chassenozjourssansespoirderetour,

Siperissableesttoutechosenée.

Quesonges-tu,monâmeemprisonée?

Pourquoyteplaistl’obscurdenostrejour,

Sipourvolerenunplusclersejour

Tuasaudosl’aelebienempanée?

Làestlebienquetoutespritdesire,

Là,lereposoutoutlemondeaspire,

Làestl’amour,là,leplaisirencore.

Là,omonâme,auplushaultcielguidée,

Tuypourrasrecongnoistrel’Idée

Delabeauté,qu’encemondej’adore.

Joachim du Bellay (1525–60), Sonnetsii

CASTLE FREKE is an earthly paradise. It stands at the top of a hill overlooking the Atlantic. Croachna, a green hill, separates south and west views, Galley Head is the boundary to the south. On the west, beyond a beautiful line of miles of coast, the pointed Stags (rocks) shut in the world. The next parish, the people say, is America. But in between the old world and the new lies the mystic island of Moy Mell, land of happy departed spirits, to be seen on clear days by the eye of faith. At night a moonlit path leads thither.

Our shore is partly sand hills, grey with marram grass, partly high cliffs, covered with heather and thrift and short grass where rabbits and puffins live amicably together. Seabirds add to the wild solitude, plover cry mournfully over Ounahincha Bog with its silver stream and its ancient cliffs, the coastline of a thousand years ago. Tiny farms and cabins lie between brakes of gorse and bracken; bo’reens (lanes) creep about the hills, their surface often raised and rocky. At the south end of the long strand is the Battery, a collection of fishermen’s cabins. Here, and all around us, live the dear people known as theneighbours, from whom I have received, with deep gratitude, unfailing affection, and who are a constant source of concern and delight.

My bedroom faces south. From my bed I see the Galley Head whose intermittent light flashes round the walls at night. I look over the sea and the Dulig Rock at whose deep foot lies a Spanish galleon, a ship laden with silver ducats, and who knows how many more hulks? I see the sandhills, and Croachna dotted with sheep and cattle.

I look down upon the tree-tops in the wood, which in Spring make a garden of bronze, pink, green and amber. Through the two wide-opened windows comes the South Wind with his freshness and scents, carrying the soft booming waves on the Long Strand.

At night the outlook is mysterious and beautiful; the shadowy woods, the moonlit sea, the Galley light and, rarely, small pricks of light from a passing ship.

These are my earliest and latest ejaculations:

“Praised be Thou, O my Lord, of Brother Wind and the air, and of the clouds and the clear, and of all the times of the sky whereby Thou dost make provision for Thy creatures.

“Praised be Thou, O my Lord, of Sister Moon and the stars that Thou hast shapen in the heavens, bright and precious and comely.”

TODAY I went to see Mrs Patrick Donovan. Her little girl Mary-Ellen has grown “distant in her mind”, which means hysterical. I am to take her to the “Children’s Hospitable” when next I go to Cork.

“’Tis fallin’ away the poor child is this last two months, and she once a fine lump of a girl.”

Mary-Ellen is only seven; a pretty little creature with blue eyes and shadows under them. She is terribly thin, arms like little sticks show through her ragged sleeves. She cries when she hears she is to go to Cork. “No then! No,” and clutches her mother’s hand.

“Och then, there’s worse happened us than that,” Mrs Donovan continues volubly, “since ye was last here the ould cow died on us, and the little boneens (pigs), they died on us for want of the milk … an’ the harse …”

“You’ve still got the horse, I hope!”

“Och then, we have a sart of a harse, but the doonkey …”

“Surely nothing has happened to the donkey?”

“Sure then ’twas ould and weak, an’ last Sunday we left it to go to Mass an’ when we got back it was lyin’ acrost the door …”

“It hadn’t, surely it hadn’t …”

“It had so. It had died on us, God help us!”

Poor creatures! Their farm is too small to keep them after they have paid their rent. The potatoes last year were diseased. The animals died of starvation. If they were to be given a cow today, they would have to sell it tomorrow to pay the rent. Their landlord is an English absentee and cares nothing for the people. “He have the hard heart,” they say, “or he’d come to see what way it is wid us all.”

The days are very full with many Poor Things coming to the house with their bundles of troubles. The little I can do to help them seems a drop in the ocean. They are desperately poor and feckless. Also they are wonderfully patient. When I am out they wait for hours to see me.

The threstill with her warblynge.

I heard it through a dream at dawn, and waking, went to a north window to hear the chorus rising from the trees on the edge of the wood. Throstle, mavis, ouzel-cock; or thrush, missel-thrush and blackbird – spraying the air with jewels of song …

Dear God, I thank Thee that I can hear them; that I am not too deaf to hear them.

FORTYCHIMNEYS have to be swept after winter’s fires, all of them are high and some are very twisty. The old Clonakilty sweep who contended with them for a lifetime has died and his son does not feel competent to carry on the work. So we have bought a set of sweep’s brooms, jointed like fishing rods. Duthie has chosen Mike Twomey to be the sweep. His workfellows jeer and wonder how he can so demean himself. When they hear that he will be paid sixpence a chimney over and above his wage, they all want to be sweeps.

TODAY I have been visiting Miss Regan, a dress-maker, strange though that seems in so small and poor a place. She is a delicate little creature, yet she plods along, living by herself in a two-roomed house.

Her father was a soldier. “This day”, she told me, “is the anniversary of the day when the Crimean War was over and peace declared, when every soldier became a hero.” Her father was a hero too, and “the night he came home to Ross he knew it”. I suppose she meant there was much “drink taken”.

The Crimean War is a reality to her, but to me Balaclava and Alma are as remote as Waterloo or Trafalgar. I remember hearing that my grandfather’sships – fine sailing ships they were – carried stores of all kinds for the troops. When I told Miss Regan this we seemed at once to become relations. How delightful that my grandfather’s ships carried food and boots and warm clothes for her father.

She was making a coat of thick frieze, woven by Hayes the weaver. “’Twill never wear out,” she said, stroking it with her thin fingers, “some person will be wearin’ it when we are all in our coffins, Godhelpus!”

WEARE HIDDEN in a sea fog as chickens under the hen’s feathers. Angel Gabriel himself could not find us. For all we know, the sea may be coming up and up on the land, filling its channels of a thousand years ago, so that when the fog has lifted we may see waves leaping on the ancient cliffs on the eastern side of Ounahincha, the tide racing between us and Croachna, sweeping up the glen, joining Rahavarrig to Kilkerran, making the hilly fields, still known by their ancient names of Great Island and Little Island, true islands once more.

What a delicious surprise! What April fools we! The sea throwing up his head and roaring with laughter and we with him!

Or supposing, under cover of the fog, this hill on which we live has come loose and is now floating into the west, so that tomorrow may see us sister island to Moy Mell!

ONEOF THE RARER joys – to look down on the tops of trees. The small leaves have broken from the purple and red buds of yesterday; all through the soft night they were pressing and straining against the sheath that held them. The garden of the tree-tops is today of amazing beauty. In a day or two the rose, primrose and bronze tenderness will be green, the incredible green of Spring, bright on the boughs of lichened and weather-beaten trees.

CASTLE FREKE is so beautiful that one grudges every moment spent away from it. One of its charms is its distance from other big houses, whose owners otherwise would constantly be descending on it with a gang of guests who would over-run the place and talk worldly talk, ask questions and go back and say things.

Isolation means a deeper love and sense – not of possession, but of being a part of something essential in the Great Scheme of Beauty and Life.

I can imagine, if I had to go to London in Spring, returning if it were possible by the next day’s mail.

THERAIN is coming down, not in drops, but in rods infinitely fine. Imagine if God sent a cold blast and froze the rods into millions of threadlike icicles reaching from Heaven to Earth, and then suppose a low sun shone out. That would be something wonderful and gorgeous in its radiance and colour; something “new under the sun” that would astonish and dumbfounder the vexed spirit of the Preacher. And then suppose that suddenly the wind set every ice-thread shaking and humming, making the strangest sound ever heard between earth and sky. What would the Preacher say then?

The primroses stand on their hairy pink legs, holding each its cup of rain. The bluebells are more easily daunted, dear feminine things; they droop their wet ringlets towards the earth, and look dilapidated.

Rain, rain! The bees are having a long Lent; there is no nectar in the sodden flowers. Jenkins feeds them with syrup. Doubtless the youngest bees, born under weeping skies, think this is the best that God can do! How little they know!

Today I met a bee whose basket was full of whitey-green pollen instead of the usual gold or brown. Jenkins, that great bee-man, believes the bee had been on the blackberry patch near the keeper’s house. He says a bee never mixes pollens. If she begins the day on blackberry she will stick to that until evening.

I like to linger beside the hives to watch the little harvesters coming in with their loads of gold from dandelion, of pale yellow from apple blossom, brown from gorse and clover, each kind in its season. I do not know if they garner the poppy’s black dust. Jenkins says the pollens are mixed in the cells, which makes one wonder why the harvesters have to keep them apart. I wonder what the proportions are? Our bees are blessed, for they live in a paradise of flowers. I wish we could isolate the hives so as to get pure magnolia honey, mignonette, violet, azalea.

Once, in the south of France, I met a small dray drawn by a donkey, on which hives of differing colours were built up. The old man who walked beside the donkey told me that he goes to the orange groves first, then changes the sections and moves cart and bees on to white clover, or heather, according to season. He travels by night, so that he does not lose any of his bees. In the daytime he and the donkey sleep while the bees work. A crop-eared chiendegarde keeps watch. One of his friends, he told me, has a hundred hives on a canal boat, but “for me the road”, he said, and I agreed with him.

Give me the wisdom of the bee,

And her unwearied industry,

That from the wild gourds of these days

I may extract health, and Thy praise,

Who can’st turn darkness into light,

And in my weakness show Thy might.

HenryVaughan,“TheBee”

ALGYWAS a good judge of character. When Arthur Sandford first came to stay with us at Castle Freke, he knew that we had found a friend.

“He is so strong”, Algy said, “that he makes me feel stronger directly he comes into the room. He doesn’t treat me as if I were a sick man.” Algy had a horror of being pitied. When we left Castle Freke on our last sad journey it was “Sandy” (as Algy called him) who took him to the boat in his brougham and carried him to the cabin. Algy, so tall but so thin, was like a child in those strong arms. The last time that he was out of doors – a week later, two days before he died, he lay through a long bright morning in his chair on the hillside – we were at West Malvern, looking at the blue distant hills of Wales.

“I wish Sandy was here,” he said after a long silence, “I wish he was here to look after you. He is such a Big Brother.”

That is what he has been to me, a big brother, an understanding friend, a tower of strength. Endless little things he has thought of to help me. Things for Jacky to do. “Isn’t he old enough to have a pony? …Wouldn’t you ride with him? Riding is so good for one … The hospitals are grateful for flowers … would you care to send some, or bring them? The sick children? … Do you ever come across patients for the Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital? Send them up or bring them. Wouldn’t it be rather fun to bring a detachment of them to Cork one day? Lunatics? No! Are there any? How mad are they? Would you like to talk to Dr Woods about them at the Asylum?” One little suggestion after another to fill my desolate days.

JOHN HENNESSY is very poor. He has no home and no one to take care of him. He has inflamed eyes, and thinks my “eye-water” beats Dr Sandford’s in Cork. Some say he is soft-like, which means a little less than daft.

He calls often for the price of a night’s lodging. I realize it would be cheaper to find him a home.

I have remembered that there is a tiny, two-roomed cabin in the glen, which stands empty. Trees shadow it, a stream runs between its door and the road. The sun touches it in the morning. No one has lived there since it was “the sprigging school” fifty years ago.

One day I ask him, “Would you like a home of your own, John?”

“I would so, me lady, if you plaze.”

“The cottage in the glen?”

“’Twould be grand, entoirely … but … ’tis a bit far.”

“Far! It isn’t two minutes from the village.”

“Could I have the impty house there? ’Tis all the pities t’have it goin’ to washte.”

“Do you mean the Parish Room? No, John.”

“That other one … how would I pay the rint?”

“The rent would be a shilling a year.”

“Glory to Goodness! A grand little house like that for a shillin’ a year.”

“Yes. A house and a bed, a table and a chair, a kettle …”

“Faix, ’tis too much! Will I get it soon?”

“In a week.”

Costello the carpenter has gone in to mend and glaze and whitewash. He is very silent and seems to know something that I don’t. Duthie the steward is also silent. Old Jerry Spillane takes his “tar’ble foine harse under the cart” to fetch furniture and some coal. Jacky and I go to see the result.

A pillow, mattress and two grey blankets are on the bed. “I should like to live here myself,” Jacky says, as we put the kettle on the hook and lay the table with a loaf and a pot of jam. John Hennessy is due to arrive at 4 o’clock.

Jacky: “He will walk in and look round and say, ‘So this is my home! Angels have made my bed and laid my tea!’ Will he say that, Mum?”

“Yes! He will have tears in his red eyes! He will say, ‘John Hennessy, you’re the lucky man to have such a grand little house.’”

It grows dark. At five we make up the fire and come away, leaving the door on the latch.

John Hennessy never took possession. His feelings were hurt! He never would have believed that the Ladyship would try to make him live in that whisht spot. What had she agin poor ould John that she should thry to force him to live where They come o’ nights to dance and do their mischiefs!

So that was the reason the house had been empty year after year. It stands on fairy ground.

Costello knew, Duthie knew, everyone knew but me. They “made a hare of me”.

A week later John Hennessy called for a bottle of “Lady Carberyship’s eye-water” – and the price of a night’s lodging.

“The hare” returned good for evil. But Carmody told the poor wretch what he thought of him.

OURWOODS are called woods by courtesy; they are not much more than belts of trees. Yet they have character and beauty and each one its own spirit. Spirit isn’t the right word … it is that which is diffused through it and which makes itself known … it is the wood but not the material wood. It is secret, shy and friendly to children and to sensitive spirits. Others it makes to be afraid.

There are places which people will not pass at night, where, they say, the wood holds and harbours ghosts. There is the White Lady who crosses the road to the garden and vanishes among the trees. She comes out of the ruined cottage which a century ago was the Priest’s house. It stood then on the road from Ross to Milltown which John Lord Car-bery, called Lard Jan by the neighbours, diverted fifty years ago, and which came out where the Rectory garden is now. There was a gate across the road to save people from going headlong into the bog.

Just there, also, Lord John and his brother the Ould Captain, dead many a year, are said to ride on the ghosts of their favourite horses. Old Duggan can remember how, when he was a boy, they waited for him to open the gate for them. There was a moon that night, shining on their faces, and they smiled at him as they rode through. “‘That’s little Duggan’, Lord John said to the Ould Captain, an’ the Ould Captain tuk a long look as he went by.”

And through the wood below Croachna, a horseman rides. He comes from the back of the old castle, crosses where the causeway ran across what was then Lough Rahavarrig and follows the old buried road through the trees and over the hill. At the closed-up gateway he stops, for it was there he was murdered. But strange to say, the day he was murdered he was coming the reverse way to that travelled by the ghost, from the West. The gate had been tied, and cursing, he got off his horse. While he was fumbling with the string, a servant who had a grievance against his master sprang up from the shelter of the wall and killed him. The man had lain there hidden while his sister, who lived on the rock now called America, kept a look-out. When the master neared the gate she gave the signal. “Hoorig, hoorig,” she cried, as tho’ she was calling the pigs to their food.

I AM MELANCHOLY because I have to go to Castle Bernard [home of Lord and Lady Bandon] for a Saturday to Monday visit. To go away from home is grief to my spirit. I don’t like going because I get so tired, and I dread practical jokes and what Beddoes rudely calls “idiot merriment”, and William Watson, more politely, “barren levity of mind”.

A party is happening. Tennis. Croquet. One hears fragments of talk. “Did you? Didn’t you? Would you? Wouldn’t you? Well, now! He said. She said.” … Doty Bandon is charming to her neighbours. The lawn is green and the trees splendid. Water-lilies shine on the pond, and gay ducks.

Mr Hurley is playing Liszt. No one listens, although he is making the piano talk. Lady M and Lady X, “bright and aged snakes”, are dissecting reputations. People talk loudly, or whisper, which is worse.

Someone shuts the windows. People are hemming me in … and stifling me …

Dear God! Why am I not listening to the lapping of the tide on Ounahincha?

Dinner. My frock is lovely. Taylor has done my hair creditably. I am wearing my pearls. I miss Algy’s approbation. I long to hear him sing as he used:

Of all the gals that are so smart

There’s none like pretty Sally,

She is the darlin’ of my heart …

The flowers are charming and the wonderful old Worcester plates a delight. Charles de Courcy, our footman, looks after me. I try hard to listen and to think of things to say. Nothing comes. I sit like a waxwork until my left-hand neighbour begins to talk. Then my brain thaws and my tongue uncurls. I can talk with the Canon [Besley] until tomorrow morning: books, poetry, folklore … His “partner” won’t have it! She seizes him. She is like a bat, dark and velvety, with sharp little white teeth. She is making the worst of him. Up in his room he has a notebook of amusing stories, which he scans when he is dressing for dinner. Lucas, a former butler of ours who also used to valet him, has seen it. No doubt Lucas drew on it for the edification of “the room” [term for upper servants’ hall]. B. [Lord Bandon] winds the Canon up and the stories begin. I forget to listen and grow absent-minded. Nothing is real. People, voices, laughter – a noisy dream. I pinch myself; my heart is beating fast; in another moment I shall faint. It is the effect of people on me; some emanation, perhaps, which is hypnotic – if not poisonous. B. looks at Doty and coughs loudly until she attends and makes a move. The cooler air in the hall brings me back to reality.

The Canon talks to Doty and me while the rest play games. She knits, with thick wooden needles, unhurriedly and after the English manner, halves of crossovers which will eventually be sewn together into Christmas presents for the poor.

I am so tired. I feel myself unravelling, strand by strand. The dogs sit round with goggling eyes, mutely imploring to be walked out and put to bed.

At last we trail upstairs, candlesticks in hand; the men stand at the foot of the stairs admiring each his fancy, while B. tries to hustle them into the smoking-room.

SUNDAY