Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In late autumn 1968, Dorian Bond was tasked with travelling to Yugoslavia to deliver cigars and film stock to the legendary Hollywood director Orson Welles. The pair soon struck up an unlikely friendship, and Welles offered Bond the role of his personal assistant – as well as a part in his next movie. No formal education could prepare him for the journey that would ensue. This fascinating memoir follows Welles and Bond across Europe during the late 1960s as they visit beautiful cities, stay at luxury hotels, and reminisce about Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, among others. It is filled with Welles' characteristic acerbic wit – featuring tales about famous movie stars such as Laurence Olivier, Marlene Dietrich and Steve McQueen – and is a fresh insight into both the man and his film-making. Set against the backdrop of the student riots of '68, the Vietnam War, the Manson killings, the rise of Roman Polanski, the Iron Curtain, and Richard Nixon's presidency, Me and Mr Welles is a unique look at both a turbulent time and one of cinema's most charismatic characters.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 338

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my darling wife, with love and appreciation.

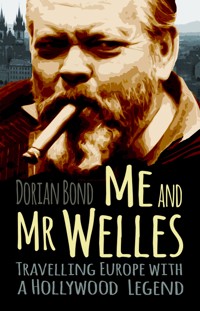

Front Cover: The habitual cigar. (Author’s Collection)

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Dorian Bond, 2018

The right of Dorian Bond to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8586 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 A Dalmatian Meeting

2 Balkan Discussions

3 Shades of 1968

4 Hair Dyeing in the Adriatic

5 Catch-22 – The Aftermath

6 The Trial

7 Across the Iron Curtain

8 The Eternal City

9 Vienna and Harry Lime

10 Ostia and Laurence Harvey

11 John Huston

12 The Tyrrhenian Coast

13 Risorgimento Discord

14 A History of Bullfighting

15 Don Quixote

16 A Voice on the Telephone

17 Breaking Bread

18 Piazza Navona and Steve McQueen

19 Bedroom Gymnastics

20 Thirteen is Not a Lucky Number

21 London

22 A New York Dandy

23 Falstaff

24 Lunar Landing

25 Black Magic and the Black Dahlia

26 Assisi

27 King Louis XVIII at the Palace of Caserta

28 A Secret Place

29 The Black Pearl

30 The Parting of Ways

31 Reflections on Cassius Marcellus Clay

32 A Close-Run Thing

33 African Perspective

34 The End Game

Epilogue

INTRODUCTION

This memoir has been written about events that happened fifty years ago, during the 1960s. The Six-Day War in the Middle East, had just been and gone as I took my final student exams and we were in the midst of what The New Yorker has called one of the most tumultuous decades of the twentieth century. So, the reader must forgive inaccuracies on exact dates, but the vast majority of it was taken from my increasingly accurate memory and the copious notes I took at the time in my little hotel room in Rome. It is all true. It is all history, although Orson Welles was dubious about written history, saying it was always written by the winners.

But I was not a winner, or a loser in these events. I was merely a participant – a witness. It was all a remarkable experience with a remarkable man, which I still cherish to this day. To paraphrase Hemingway, if you are lucky enough to have worked for Orson Welles as a young man, then the experience will go with you for the rest of your life, for Orson Welles is a moveable feast.

A feast he was, and I ate my fill.

There are few giants in this world of pygmies and he was one. To quote Shakespeare’s Cassius:

He doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonourable graves.

The boy who grew up in Kenosha, Wisconsin, attended the Todd School outside Chicago, turned down a scholarship to Harvard and instead headed out into the world to seek his fame and his fortune, was truly a renaissance man.

His ashes now lie in faraway Andalusia, free from the chaos of his life and the art which gave us all such a unique vision. I was lucky enough to have been up close and personal with him. I salute his memory. As he always said to me, ‘Nobody gets justice. People only get good luck or bad luck.’

I lived long enough in China to realise that he was dead right. The Chinese set great store on luck, but what supersedes success or failure is the importance of being true to yourself. Orson Welles never let us down in this respect, so I originally thought of calling this book, The Importance of Being Orson.

Whatever it’s called doesn’t really matter. It’s about him.

Dorian Bond

Winchester, England, 2018

‘The time has come,’ the Walrus said,

‘To talk of many things:

Of shoes – and ships – and sealing-wax –

Of cabbages – and kings –

And why the sea is boiling hot –

And whether pigs have wings.’

Lewis Carroll

1

A DALMATIAN MEETING

‘Dorian St George Bond! With a name like that, you’ve just gotta be a movie director!’ roared Orson Welles. When Orson Welles roared, it could be heard a mile away. Literally.

He was towering over me, which he obviously would do, given that he was a good 6ft something in his socks – I was a flattering 5ft 8in, and anyway, he was standing on the side of a luxury sailing yacht already a couple of feet above the level of the jetty I was standing, or cowering, on.

He was wearing the famous black fedora hat, a black shirt buttoned to the collar, a black suit and black shoes. He was not to wear anything else during the time I was with him. It was a kind of style or uniform that he was comfortable with. It looked good. A Montecristo was sticking out of his mouth, half smoked and half chewed.

All in all, he was a magnificent figure, the image very much reflecting the legend. He might as well have been Charles Foster Kane.

*

‘Can you go to Yugoslavia tomorrow for Orson Welles?’

‘Yes,’ I answered, without missing a beat. They say to be impulsive is a bad thing. This time it was definitely a good thing.

The telephone had just rung and an old lady’s voice, very Miss Marple, had asked, ‘Is that Dorian Bond?’ I had said yes and she had continued, ‘My name is Ann Rogers, I’m Orson Welles’s private secretary. Can you go to Yugoslavia tomorrow for Mr Welles?’

I confirmed my original reply.

It was the late autumn of 1968: the Battle of Khe Sanh had been fought and lost, and the Tet Offensive had finally been suppressed after savage combat in Huế, immortalised by those dramatic Don McCullin photographs of US Marines fighting and dying in the ruins of the ancient city. In March, I had taken part in the protest against the war in Vietnam which ended with violence in Grosvenor Square. In April, Martin Luther King had been assassinated in Memphis, while in May, Danny Cohn-Bendit had manned the barricades in Paris, and in June, Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated in Los Angeles.

The Prague Spring, which had brought us the sympathetically sad face of Alexander Dubček, had blossomed on his accession to power in January and died with the Eastern Bloc armed forces brutally suppressing the Czechoslovak people at the end of August as the West looked on. Yale had decided to accept women undergraduates, and Richard Nixon had been elected president, completing his comeback from his close-run defeat to Kennedy in 1960 and the humiliation of his failure to win the governorship of California in 1964. Finally, the Troubles in Northern Ireland were just about to begin.

I had sat next to Paul McCartney and Jane Asher and been introduced to Eric Burden, he of ‘Rising Sun’ fame, at the legendary Scotch in Masons Yard in St James’s, that cooler than cool place where Jimi Hendrix had played his first time in London, where the Rolling Stones hung out and where McCartney met Stevie Wonder. I really thought I had my finger on the pulse of contemporary London.

It was a long time ago. Or so it seems to me now.

One evening, I had supper with two friends of mine from university. He had started in the considered world of publishing while she was drifting from job to job. Fiona told me that she had just run an errand for Orson Welles.

‘Orson Welles?’ I nearly choked on my mouthful of goulash. ‘You ran an errand for Orson Welles? Amazing! Did you actually meet him?’

‘Yes,’ she said airily as if it was the most normal thing in the world to do, run an errand for Orson Welles.

I have to point out to you here that I was at film school, where Orson Welles was not merely a mortal man – he was worshipped as a god by teachers and students alike. There were posters of him in his fedora all around; in fact, those black and white images of him in a number of his films fitted seamlessly on the dank, blackened brick walls of the film school which had once been a fruit and vegetable warehouse. You almost expected him to appear out of the shadows, like Harry Lime, as you mounted the dark stone stairs or turned any corner.

And now, out of the blue sea of the Mediterranean, unbeknownst to him and unbeknownst to me, we seemed to be within touching distance.

And delicious chance had been the instigator, as it is of most things in our lives. Predestination, the Calvinists of Geneva called it. Fate, fado, fatalite, sino, Schicksal, or whatever word you want to use.

Human beings, for some reason, are always surprised by change, hostile to change, uncomfortable with change. It’s as if we think the rhythm of life will never change. It gives us that feeling of security. When that rhythm does change, we feel insecure, vulnerable, exposed.

But one thing in life is certain: change is inevitable, whether it be a change of pace, a change of location, or a change of personnel. And nobody wants it, expects it, or welcomes it. Most people are afraid of it. But artists create it. By showing us lesser mortals a different way to look at the world, they expose us to this insecurity. It can turn us on, when we hear a particular passage of Shakespeare or a combination of notes by Mozart, or when we look at a juxtaposition of colours by Vincent van Gogh. Or it can disturb us, like a passage from Samuel Beckett or a swathe of orchestral passages from Sibelius or a portrait by Francis Bacon.

Anyway, Fiona had been visiting her tax-exiled parents in Majorca, wondering what to do next with her life. On the beach she had talked to some little children and paddled with them in the clear, azure waters of the Mediterranean. By chance, it transpired they were the grandchildren of an infamous woman. They were the children of the son of none other than the disreputable Lady Docker.

In the dreary 1950s, with England still recovering from post-war rationing and huge swathes of London and many major cities across the land still proudly displaying the burnt-out carcasses of warehouses and industrial buildings bombed by the Luftwaffe, Lady Docker was a byword for poor taste, extravagance and vulgarity all rolled into one. She had illuminated puritanical Britain with enough scandal and ill-chosen remarks to shock every class of person. The upper classes despised her for her vulgar behaviour, while the working classes hated her for her outrageous expenditure in times of such hardship.

Starting out from a modest background in Derbyshire, she moved to London to become a dance hostess, and had married successively three millionaires, rode around in a gold-handled Daimler, spent money like water, and was even banned personally from Monaco by Prince Rainier for tearing up the Monegasque flag on hearing that she could not bring her son Lance to the christening of Prince Albert, to which she and her husband had been invited.

Such is fate. In 1968 she was in Majorca, not the South of France, from which she had also been banned by virtue of an agreement between Monaco and the French Government.

Anyway, her daughter-in-law was sitting on the beach talking to Fiona and was the mother of these children. She lived in sedate Maida Vale, and was a neighbour of a certain Ann Rogers. Maybe she could do something for the floundering Fiona.

On her return to England, Fiona made contact with Mrs Rogers. It transpired that she was the personal secretary of the legendary Orson Welles. So, she was sent on a mission for Orson Welles. She ended up on the Yugoslav coast bearing gifts to Mr Welles of Kodak 35mm raw stock. She stayed a few days and then departed. Unlike me she was not obsessed with movies.

I sat dumbfounded for a few moments, then asked the classic question, ‘If Mrs Rogers asks you to do the trip again, can you please give her my name?’

Grant grinned elegantly at me, thinking me mad. He had always reminded me of a Chinese mandarin after a good dinner, or a large Persian cat after it had eaten a mouse. He lived in the urbane world of publishing, where little was done in a hurry and movies were at the bottom of the food chain.

‘Of course,’ said Fiona.

I thought she was lying – of course she was lying. Who on earth in their right mind would pass up the invitation to go down to the Dalmatian coast and hang out with Orson Welles?

Fortunately, the world is not full of grotty film students.

As I walked home, I put the whole thing out of my mind. Nothing would come of it.

*

‘In France all the cineastes became obsessed with my work. I could never understand why! You know, Truffaut and the boring Jean-Luc Godard. He was a Swiss, you know, very rich and always trying to intellectualise film-making. What the hell has existentialism and Marxism got to do with movies? It’s a European sickness!’

So true, I thought, as he chuckled to himself and chewed on his unlit cigar. I had fallen asleep in both À Bout de Souffle and Pierrot le Fou.

‘One good thing you could say about him, he’s worked with some beautiful women! He’s made more films than I have and he started twenty years later.’

He relit his cigar.

‘That’s one thing people get right in Europe. They make films for reasonable budgets, unlike Hollywood where money is the only object. Those Hollywood guys have got themselves a good racket and they’ll milk it for all it's worth. Who wouldn’t? It’s foolish men like me who can’t see where art ends and business begins.’

*

Ann Rogers was a tweedy lady, like a large flightless bird, the then extinct Great Bustard, perhaps 60 years of age which, to my 22 years, seemed elderly. She was one of those people who had probably always been that age.

*

‘People have ideal ages, don’t they? Young men who will be more comfortable in their fifties and pretty middle-aged women who clearly peaked when they were sixteen. You, Dorian, I suspect will be in your forties.’

I asked him what about himself and he laughed, ‘Now. Now is always my ideal age though everyone tells me it was when I was in my twenties.’

‘He’s always gonna be young,’ interjected Oja, ‘young in mind.’

‘And in heart,’ he added, reaching over to take her hand.

*

Ann Rogers explained that she ran Mr Welles’s business affairs in London. She lived in a large and comfortable apartment in Maida Vale, that discreet corner of London named after an even more discreet military victory won by the British over the French in Calabria in 1806. She was married to an Australian who hardly knew who the hell Orson Welles was and was more interested in beating the English at cricket or reminding us of their efforts at Gallipoli. When I pointed out to him that far more British were killed on that godforsaken Turkish peninsula than antipodeans, he was affronted.

Mrs Rogers told me that ‘Mr Welles’ was filming in Yugoslavia and needed some essential supplies. With no more ado, she handed me a large bundle of £50 notes, probably more cash than I had ever seen in my life before, and instructed me to go to two places in central London: the headquarters of Kodak in Covent Garden to buy ten 400ft rolls of 35mm film and Alfred Dunhill in Jermyn Street to buy 100 No. 1 Montecristo Havana cigars. These were the ‘essential supplies’ for ‘Mr Welles,’ as she called him.

Nothing else, just film and cigars! Something from Cuba, something from the USA – very Orson Welles, I thought. I liked it.

She also gave me enough cash to buy two top-of-the-range suitcases to house the film stock and the cigars. Her instructions were crisp and matter of fact and suited her tweed suit. I imagined her working for the Special Operations Executive in the war, efficiently sending agents off on deadly missions, many of them never to return. Or at Bletchley Park, valiantly typing up incomprehensible documents for shabby-suited academics with minds filled with numbers, codes and mathematical formulae. England seems to breed ladies like Mrs Rogers in abundance, whose driving force is duty, duty and then duty.

The next day, it was November I remember, I flew out of a grey, overcast and rainy London on a Jugoslav Aero Transport Caravelle to the Adriatic port of Split, the Roman and Venetian Spalato, where the Emperor Diocletian had built his great palace, grew cabbages, and gently debauched himself far away from prying Roman eyes.

As time passed in mid-air, I remember thinking Dr Johnson was quite wrong. I was bored with London. Well, at least with the verbosely named London School of Film Technique, a disused Victorian warehouse in Covent Garden, a far cry from the elegant quadrangles and colonnades of Oxford, where the fruit and vegetable market still ruled the roost.

The school was run by the pretentious, cheap-cigar-smoking Robert Dunbar who, having failed to achieve anything of worth in the movie industry, was making a living by overcharging naïve young would-be film-makers with disorganised lectures, random courses and out-of-date equipment. He was the epitome of the Oscar Wilde aphorism about teachers.

Unbeknownst to me, he was also a keen advocate of the dreaded ACTT, the Association of Cinematograph, Television and Allied Technicians, the trade union which was the Stasi of the British film industry. To work you had to have an ACTT card, but you couldn’t get a card without a job and you couldn’t get a job without a card. This resulted in a huge amount of nepotism in the business, where families tended to follow each other into particular professions. I had no family connections, but through one contact managed to get an interview with the head of production at Shepperton Studios.

I told some pathetic story of how I had run my school film society with screenings of Citizen Kane and other classic films. On one occasion, I had even organised a trip to Shepperton during the filming of Becket and had watched Richard Burton and Peter O’Toole on the set. Thinking back, my approach was pretty lame. This man was a technician and operative disinterested in the idea that film was art. For him, as with most technicians in the industry, it was a business, a technical business, like working in a factory. I subscribed more to the Mr Welles school of film-making: he told me he’d learnt all he needed to learn about the workings of a film camera in two days with Greg Toland.

Anyway, the Shepperton man told me that if I could get an ACTT card on the recommendation of Robert Dunbar, he would give me a job in production. It was a chicken and egg situation. Suffice it to say that my request to the seedy Dunbar was turned down on the grounds that, if he gave me a card, then he would have to give one to every other student. Since most of them were foreign nationals, I didn’t see this as a problem and went away disappointed.

The ACTT was one of those ineffective trade unions where most of its members were permanently unemployed so the notion that it protected them was a nonsense. It fought back against movie producers by insisting on the most ridiculous crewing requirements. For example, four men were stipulated on a camera crew: the lighting cameraman or director of photography, the first assistant cameraman or camera operator, the second assistant cameraman or focus puller, and finally the third assistant cameraman or clapper boy, who loaded the 35mm magazines and operated the clapper board. This was fine on a major film, but on low-budget productions it was simply not necessary. Overtime was strictly adhered to, so the rules of the factory floor were implemented in film-making, which never made a lot of sense to me. The cars of film crews, when they turned up for work in film studios, were very top of the range – no struggling artists here, just hardnosed technicians like expensive electricians or plumbers.

The film school was a massive disappointment, a far cry from the wit and repartee of university, full of American Vietnam draft-dodgers, melodramatic Italians with no talent, boring Swiss, pretentious Iranian wannabes with nothing better to do with their lives, numerous left-orientated students and a myriad of other deadbeats. After the effete delights of Oxford, it was a huge comedown.

The one highlight for us men was a magnificent Israeli by the name of Osnat Krasnansky. She had served with the Israeli Army during the 1967 war and a bunch of unhealthy-looking film students were no worthy opponents for her when she had personally captured a whole unit of Egyptian infantry in the Sinai single-handed. With her tanned skin, her shining white teeth, her black tresses, black eyes and the body of an Olympic athlete, she was a girl apart.

Another singular person I met there was a tall, lugubrious young man named Robert Mrazek, a Cornell-educated American who had volunteered for service in Vietnam and had become an officer in the US Navy. Unfortunately, he had been partially blinded in a gunnery accident and sported a black patch over his injured eye like Nelson. We would compare notes most evenings in his dimly lit and dank flat overlooking the Thames in Pimlico, normally beginning with an earnest discussion on the early works of Lubitsch and Bergman, followed by enthusiastic slagging off of our fellow students, then further earnest discussions about our mutual heroes, President Kennedy, Horatio Nelson and, of course, the unattainable Osnat Krasnansky.

The few memorable moments at the school were lectures with Charles Frend, the director of Scott of the Antarctic and The Cruel Sea, talks by Roger Manvell, the first director of the British Film Academy, on the Nazi film propaganda machine, and an illuminating appearance from two young Czech directors, Ivan Passer and Milos Forman, recently escaped from Russian-occupied Prague. I had seen Forman’s first film, Loves of a Blonde, a charming and funny black and white movie. He and Passer told harrowing stories about their difficulties under the Russian occupation. A few weeks later, Forman went to Hollywood and went on to direct a number of films, including One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Amadeus.

*

‘I turned up at the Gate Theatre in Dublin and told them I was a Broadway star. I was sixteen, I think. They gave me a star part in their next production. So, I started as a star and I’ve been working my way down ever since!’

2

BALKAN DISCUSSIONS

I was met at Split airport by a Yugoslav youth, Mirko, who chain-smoked the strong local Sava cigarettes, drove me to a small fishing village a little way up the coast called Primošten and installed me in the completely deserted hotel, the only one in town. It wasn’t quite the Bates Motel, but not far off, a sort of Mediterranean version of the hotel in The Shining with a hint of the Iron Curtain about it. Commissars from Hungary and middle-ranking Stasi agents from East Germany doubtless summered there with their fat, ill-dressed wives.

‘Do you want to rest, or what?’ Mirko asked me abruptly.

Holding up the enormously heavy suitcase, I suggested we go and tell Mr Welles that his goods had arrived. We proceeded down to the little port with its leisure boats wrapped up in canvas covers for the winter and drove along the deserted jetty towards what was evidently a small film crew, who were working on the deck of a large yacht.

I got out of the car in the fading Mediterranean light and approached. There was a cold breeze blowing, making the halyards rattle against the unused masts. Orson Welles stood on the yacht holding onto the mast for stability.

There was no doubt it was Orson Welles. He was enormous, tall, broad, all in black with a black cloak and a black hat, very much the magician, which, of course, he was.

*

‘Cinematography is a form of conjuring. Interiors may be in a studio while the exteriors may be an amalgam of completely different locations. A doorway out of one room leads you to a location 1,000 miles away but it looks real. The audience have been tricked. Nothing is what it seems.’

*

I had seen hundreds of black and white photographs of him, and there he was, the man himself standing alone on a borrowed yacht in a deserted harbour on a little-visited coastline.

His film crew were huddled below decks when I arrived, presumably attempting to stay out of the biting wind. People think it never gets cold in the Mediterranean. Believe me, it does. I have to repeat here I was not a very tall young man and Orson Welles was a very big man in every sense of the word, a big presence with a big black cloak and a big black hat and a big deep voice. You get the picture?

‘Mr Welles?’ I asked, knowing perfectly well to whom I spoke, ‘I’ve brought your cigars and film stock.’

That was the first time I ever addressed him. I called him ‘Mr Welles,’ as Mrs Rogers did. For me it was a sign of respect from a young man to an older man. But it was not just that. It was more. I did respect him, genuinely. And I wanted to reinforce it to him, so he understood where I stood with him. Not subservient, but junior to him. It always bugged me when people of all ages who’d known him for five minutes called him ‘Orson.’ I suppose it’s a little old-fashioned, but there it is and he accepted it. Although we were in a theatrical world, we had both been brought up old-style and that was the way.

I stood still, waiting for the real-life Orson Welles to speak his unforgettable first words to me. I have to repeat them, I enjoy them so much.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘you must be Dorian St George Bond. With a name like that you’ve just gotta be a movie director!’ With that, he roared with laughter and the crew chuckled in unison. He then told me to go back to the hotel and wait for him.

As historic meetings go, this one obviously doesn’t rank very highly in the scheme of things. I never met Dr Livingstone in Africa or the Duke of Wellington after the Battle of Waterloo. I was certainly no Henry Morton Stanley or Marshal Blücher. But it was historic for me, and it had the format of importance in that we both instantly knew who the other man was. I cherish it to this day.

So, I sat in the deserted, white summer lobby of the Dalmatian hotel and waited nervously for the great man. Maybe he would just take the cigars and Kodak and say, ‘thank you and goodbye.’ At least I would get a night on the Dalmatian coast, albeit in winter when all the bars and restaurants were closed, before returning to London.

After about an hour, Welles and his mini-entourage swept in. He immediately began talking to me in the most charming manner: How was my flight? Had I been to Yugoslavia before?

This was my moment. I considered myself an expert on Yugoslavia. I told Mr Welles that, yes, I had been to Yugoslavia on a number of occasions before, and in fact my stepmother was a Serbian émigrée whose father had been court jeweller in Belgrade to the charismatic King Peter I of Serbia before the First World War. The king had regaled him with stories of his military exploits. He had fought with the French Foreign Legion during the Franco-Prussian War, been wounded at Orléans, and only managed to escape the Prussians by swimming across the Loire.

Milan Stojesiljevic and his young wife, parents to my beloved stepmother and her brother, had succumbed to influenza in the great outbreak of 1919, leaving their two infant children as orphans. I rattled on with the tale of how the two children survived their privileged but lonely childhoods, with Katerina being brought up by maiden aunts and Nikola attending boarding school followed by military academy, how she married, very young, an equally young heir to a mercantile fortune who died shortly thereafter of tuberculosis. By this time, I was getting quite carried away, telling Mr Welles that I loved the Serbs who had been our Allies in both the Great War and the Second World War and that I hated the Croats, many of whom had served in the SS and had killed more than a million Serbs in concentration camps.

He seemed amused by my outburst, and smiled mischievously. When I finally drew breath, he coolly introduced me to a tall, striking-looking young woman in her mid- to late twenties who was watching me stonily. She had a strong Slavonic face with a hint of Mongolian origins from centuries ago. ‘This is Olga Palinkaš and she is a Croat.’

‘Call me Oja,’ she smiled menacingly at me through her perfect white teeth. ‘We’re all Croats here.’

I mumbled a pathetic apology, while Mr Welles enjoyed the moment and roared with laughter. ‘You’re in the Balkans here, boy, so beware!’

I later discovered Oja’s father was Hungarian, so I felt a little better. Over tea, they told me how they had first met in Zagreb in 1962 when Welles was shooting Kafka’s The Trial. Oja told me that she was studying at the School of Fine Arts and had been out with a friend of her parents at the legendary Esplanade Hotel. In the bar, her friend had suddenly said to her, ‘Orson Welles, the famous film director, is sitting right behind you. Don’t look.’ Of course, she looked, only to be confronted by a lot of indoor palms, behind which was the instantly recognisable Mr Welles.

‘She was so beautiful that I came right across to talk to her. And that was it.’

‘Well, not quite!’ said Oja, ‘A few things happened in between.’

‘You tell him the story, I enjoy hearing it.’

‘So we talked for ages and ages at the bar. Mainly about art. Then you invited me to watch the filming and told me you would send a car for me in the morning.’

‘Always, a gentleman,’ breathed Mr Welles.

‘And, sure enough, the car duly arrived. A big car, and there were hardly any cars in that area outside Zagreb at that time! So, all my neighbours were looking. And at the location I was very embarrassed because when I walked in everybody stopped and looked at me.’

‘You were so beautiful.’

‘I met Tony Perkins, Orson’s big friend, and all the others.’

‘It was grand.’ Mr Welles was getting a little bored with the story now and was looking about the room.

‘And that was how it all started?’ I asked.

‘Yup,’ grunted Mr Welles.

‘Not exactly, my love,’ Oja laughed, ‘You never called me. You just left Zagreb and never called. I didn’t know what to do. I was very upset by you.’

‘I’m sorry,’ he exhaled. ‘We had to leave. The local production company were overcharging grotesquely and there was no way we could pay. The Salkinds had run out of money. The Zagreb people thought they had us over a barrel, so we just left town.’

‘It was two years later. I was in Paris studying fine arts. I lived in a little garret on the Faubourg St Antoine. Right at the top.’

‘And I found you. And I walked right up and broke down your door when you refused to open it to me!’

‘And that was it. We fell in love.’

‘Wow,’ I said.

With that, Welles bade me good evening and told me to meet him for breakfast at 5.30 the following morning.

It occurred to me that this was a case of the comfort of strangers. I was a stranger, or at least a new kid on the block, and they could tell me this pretty intimate story with impunity. I would be gone in a few days and who could I tell?

Weeks later, when Oja could see me thinking about their age difference, she quickly dispelled my image of the old fading film director with the young budding actress. ‘He’s the youngest-spirited guy I’ve ever met, fun, loving, imaginative, mischievous, everything. The idea he’s old is ridiculous. Very often he’s younger than me.’

The Yugoslav youth, Mirko, also a Croat (after all, we were in Croatia), asked if I’d like to eat with his family. I was thankful for the invitation, since the hotel restaurant had the look of a communist canteen, and went with him to a fisherman’s house where we were cooked fresh sardines and drank Dalmatian wine. I wondered whether Raymond of Toulouse and his fellow Crusaders had eaten half this well as they trudged down this desolately beautiful coastline a thousand years before me. After all, Diocletian had lived happily here for a number of years in his retirement.

I slept nervously, wondering whether I would be sent back to the shoddy realities of film school, with its smell of rotting cabbages, the following day. Diocletian again.

*

‘Did you know that one of the best places to buy Cuban cigars in the world is Communist China? The two Communist brother countries find their trade a little imbalanced and the only thing the Cubans can offer to them is their cigars, that ultimate symbol of the capitalist world.’

‘They should name a cigar after you,’ I ventured. ‘After all, there’s a Churchill.’

‘Churchill was Churchill,’ Mr Welles growled, before taking another puff. ‘He came round to my dressing room once in London when I was playing Macbeth. He quoted one of my speeches, then continued on into the rest of the speech which I had cut out to make the play less tediously long! He didn’t miss a trick!

‘I’ll tell you a funny story. He was out of power then. Having presided over one of the most important events in world history alongside dear old FDR, he lost the election. I suppose rightly. He was a little out of date by then, a man who had charged at Omdurman against the Fuzzy Wuzzies. Anyway, I was in Venice on the Lido trying to persuade an expatriate Russian Armenian to put up some money for me for a movie I’d written. As we walked through the hotel lobby to lunch, Churchill was standing there with Clemmie and we nodded to each other. At lunch the Russian was suitably impressed. Actually, he wasn’t just impressed, he was bowled over! How on earth did I know one of the architects of the Allied victory in 1945?

‘The next day I was swimming opposite the hotel and suddenly found myself near Churchill.

‘“Mr Churchill,” I said, “I have to thank you for acknowledging me yesterday. The man I was with is being pursued by me to invest in a film I plan to make. He thinks I am very well connected.”

‘“Little does he know that I am no longer Prime Minister. Russians are not familiar with our democratic systems!”

‘With that, he swam away and joined Clemmie on the beach.

‘That evening, as I walked into dinner with my Russian friend, we passed Mr Churchill’s table. Without hesitation, Churchill stood up and bowed deeply as I passed.’

Mr Welles enacted the bow and we roared with laughter. Here was one of the most famous actors in the world charmingly re-enacting a scene from his past when probably the most famous man in the world had bowed to him in jest. A wonderful moment for me.

I told Mr Welles some days later that I had attended Churchill’s lying-in-state in Westminster Hall in January 1965, and with all the other people of England had shuffled past his coffin illuminated by four great candles and bowed my head. The next day I had stood in the grey January day and watched his coffin go by on a gun carriage and felt this was truly a marker of the end of empire, the end of Britain as a world power.

‘Did you know Churchill ran most of the war drunk on cognac? That’s why he got along so well with that old rogue Stalin! Poor FDR was most disapproving.’

I then told him the Churchill Yalta story. At the conference, the three world leaders would sit around the table with their aides. Notes were passed between them constantly as the talks progressed. One day, Churchill passed a note to Anthony Eden, his foreign secretary, which the Russians managed to retrieve from a wastepaper basket.

It read, ‘Dead birds don’t fall out of nests.’

Stalin was intrigued. Surely this was a code about some diabolical act the Allies were planning. For days the NKVD, the predecessors of the KGB, attempted to break the code. They failed. Stalin was at his wits’ end. That evening after dinner, when he and Churchill were having a drink together, he asked the question.

‘Mr Churchill, I have to ask you something. It’s about a note you wrote to your aides some days ago. It said, ‘Dead birds don’t fall out of nests.’

‘Oh, that,’ smiled Churchill wryly.

‘We are Allies, Mr Churchill, please enlighten me.’

Churchill took another mouthful of Cognac. ‘It isn’t a code, Secretary Stalin. It was a reply to a note from Mr Eden telling me my fly buttons were undone!’

3

SHADES OF 1968

‘We skipped the light fandango, turned cartwheels across the floor, I was feeling kind of seasick …’ The BBC’s Radio 1 was blasting out ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ by Procol Harum which, a year before, had been the soundtrack to my final exams at Oxford. It made me feel a little bittersweet aware that those days had now gone and I was wondering where my life would take me. I sat in my car listening to the music playing for a long moment before getting out, filling up with petrol and going in to pay and buy a sandwich.

As I climbed back into my car, the track changed to the sophisticated sound of Dionne Warwick’s ‘Do you know the way to San Jose.’ As she reached the line, ‘LA is a great big freeway,’ the programme was interrupted: ‘We are getting news that Senator Robert Kennedy has been shot in Los Angeles.’

I froze in my seat and didn’t move. The track continued, the DJ made some lame remark, and I flicked through the channels to find out more. The BBC News gave me the answer:

Bobby Kennedy, Senator Robert Kennedy, the front-runner for the Democratic nomination for president in the forthcoming US presidential election, has been shot and severely wounded. He was just leaving a Democratic victory celebration when he was shot. We will bring you more news as we receive it.

Five years before, as a schoolboy, I had heard about the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and watched dumbfounded as the events unfolded, from the sight of the bloodied Jacky Kennedy on the steps of Air Force One, to the chaotic swearing-in of Lyndon Johnson inside the aircraft, to the sombre funeral on the streets of Washington a few days later. It seemed the deaths of the two Kennedy brothers had bookended my time at university, along with the death of Winston Churchill – 1963, 1965 and now 1968.