14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: Edition Noema

- Sprache: Englisch

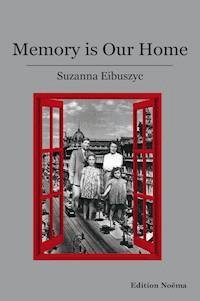

"Memory is Our Home" is a powerful biographical memoir based on the diaries of Roma Talasiewicz-Eibuszyc, who grew up in Warsaw before and during World War I and who, after escaping the atrocities of World War II, was able to survive in the vast territories of Soviet Russia and Uzbekistan. Translated by her own daughter, interweaving her own recollections as her family made a new life in the shadows of the Holocaust in Communist Poland after the war and into the late 1960s, this book is a rich, living document, a riveting account of a vibrant young woman's courage and endurance. A forty-year recollection of love and loss, of hopes and dreams for a better world, it provides richly-textured accounts of the physical and emotional lives of Jews in Warsaw and of survival during World War II throughout Russia. This book, narrated in a compelling, unique voice through two generations, is the proverbial candle needed to keep memory alive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 512

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

The past is never dead. It's not even past.

William Faulkner

This book is based on my mother Roma Talasiewicz-Eibuszyc'sdiary, her writings about Warsaw,Poland during theyears following World WarIandthe sixlongyearsofWorld War II,and how shewas able tosurvivein SovietRussiaand Uzbekistan. Interwoven with herjournalsare stories shetoldto me throughout my life, as well as my own recollections as my family made a new life in the shadows of the Holocaust in Communist Poland after the war and into the late 1960s.By retelling thisstory Itry to shed light on how the Holocaust trauma is transmitted to the next generation, the price my family paidwhen we saidgood-bye tothe old world,and the challenges wefaced in America.

For my daughters:

You possess the voice that Roma's generation was forced to silence.

S.E.

In loving memory:

Bina Symengauz and Pinkus Talasowicz,

Adek, Pola, Sala, Anja,and Sevek

Their five young children

Icek Dawid Ejbuszyc and Ita Mariem Grinszpanholc,

Sura-Blima and Dwojra andJakub-Szaya

Dedicated to:

Mother and Father and the memory of

their generation that perished in the

Holocaust

"Seen and Unseen"A foreword toMemory Is Our Home

There are many reasons why survivors decide to record their memoirs. In cases recounting the pre-Holocaust and Holocaust periods, memoirists are often explicit: to bear witness to human cruelty; to speak on behalf of those who were killed; to help successive generations understand what happened to families and a people; to describe how they survived; or to warn about the possibilities of injustice and therefore to seek justice. All these reasons are represented in this memoir, but I am particularly interested in one apparent reason that memoirists, as a rule, don’t mention: memoirs give victims a "voice." Memoirs are expressive as well as instrumental. They play a key role in memoirists’ transition from victims to survivors. They achieve standing by reconstituting their self-respect after periods of profound humiliation, helplessness, and traumatic fear. As such, survivors’ memoirs are important for deliberating on life after ambient death. No other genre is dedicated to exploring this surprising reversal of the natural order.

This memoir, however, is unusual. It is not only the result of a conversation between mother and daughter; it is also constructed in two voices. We learn about the past and the present, or more technically, about intergenerational transmission. I am drawn to the mother’s direct account of her experience in Poland between the two world wars, the new realities she encountered, and her life-changing disillusionment that resulted from an exposure to aggressive behavior that came as a complete shock to her and her generation of Jews who were looking forward to an affirmative life. "Home," as in the title of this memoir, would have to materialize where it could: in survivors’ memories.

This story takes place after Poland gained its independence in 1918. Roma was born the year before. We overhear Roma telling Suzanna about her family and its Jewish traditions, her romances, and her Jewish and Catholic neighbors. We learn about the family’s economic hardships and struggles for its livelihood. These stories matter to Roma, but she concerns herself with the deterioration of life for Jews in the 1930s as a result of popular and organized anti-Jewish hostilities. She reflects on the destruction of Polish Jewry during her and her sister’s relocation to Russia during World War II. As acute as her observations are, they are deeply emotional. Suzanna tells us that her mother suffered irreparably: "She was forever haunted by horrific memories….She never stopped mourning." Roma, herself, recalled the "unrest" she felt each day. Virulent anti-Semitism would surely explain that, but it didn’t help that she played an active part in the political opposition to the ascendant fascist National Democratic Party: "The mailman looked at me suspiciously. I was sure that police inspection would follow. Being guilty by association was one of the biggest fears in those days."

Suzanna writes about inheriting the emotional burden. One of the significant narratives in this double memoir is the urge for both mother and daughter to remain invisible, to live in psychological hiding, or, as Suzanna commented about her own life, "to be unseen and to be afraid, lest be subject to some kind of harassment." Being invisible was, indeed, the price Roma paid for self-protection from political reprisal and anti-Semitic attack. The fatal paradox of Roma’s predicament – indeed, for all members of a vulnerable minority, whether by political choice or by dint of pedigree – was the exigent condition of secrecy, for a furtive existence fuels a vicious cycle of suspicion and further self-concealment.

Roma’s story provides testimonial confirmation of a landmark scholarly argument for local culpability in the destruction process during the Nazi era. Launched in 2000 by the Polish-Jewish émigré intellectual Jan Gross, the case for villagers turning against their Jewish neighbors has revised the standard view, which is still salient among students of the subject, that the central Nazi state was exclusively responsible. As she reminds us, Jews felt vulnerable before the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939. She tells us about her neighbors' dedicated hostility. Indeed, Roma observed that Poles did not see Jews as true Poles, a reality reflected in the distinction she made – significantly, in passing – between a Pole and a Jew. She referred to her childhood's building's courtyard as a self-imposed "prison" where she felt safe. It's surely not by chance that she devoted considerable space to actual prisons where local officials detained her political comrades. Life before the Holocaust became progressively restricted for Polish Jews. Suzanna ratified the account: "Poland, as a nation, has to face its demons."

Importantly, Roma also recalled feeling hopeful. We often read survivors' memoirs as testaments to human degradation, and, indeed, Roma felt "an obligation to bear witness." As Suzanna rightly states, her mother's memoir is a story of tragedy and triumph. But for Roma triumph was not something to declare. Her decisive inclination to look forward, even as anguish darkened her daily existence, was evidently important enough for her to recall that she did so in great detail. Congruent with her time, Roma was a true believer. Her cause was the achievement of human and common national fellowship. We get hints of this early on in these pages: her youthful zeal for learning the Polish language, or her love for the movies and Polish (not Polish-Jewish) literature that opened her eyes "to [the] world outside my immediate surroundings." Her description of Warsaw's streets was particularly evocative – the magic of its beautiful boulevards and elegant store windows. After returning from Russia, she reminisced about "my once beloved city" and her "beloved Poland," a disposition that Suzanna confirmed, for herself as much as for her mother.

Roma joined organizations before World War II that promised a future when Jews and Poles could "coexist." The Socialist Bund movement represented her commitment to making Poland a great country "for all workers." She also joined a workers Esperanto movement to help promote communication across social factions. She participated in the currents of the Jewish Haskalah, or Jewish enlightenment, that, from the 18thcentury on, redefined Jewish tradition in terms that could ease modern Jewry's integration into secular society. For Roma, this meant affirming her Polish patrimony, but also following a Jewish way of life that, for example, permitted her to venture out to the movies on a Friday night, the Jewish Sabbath that traditionally proscribed such activities, or to regard romance and marriage as a matter of love and not as a means of preserving religious or ethnic boundaries (though she respected those boundaries for herself). A member of her family elected to live in a Polish (Christian) neighborhood. As Suzanna remarked, "My mother's homeland never stopped being part of her very essence."

The real story we can glean from Roma and Suzanna's tandem memoir is what Holocaust survivor Primo Levi called inner "unseen realities." From the outside, the historical narrative about modern Jewry is a delineated story of Jewish attempts at social integration and anti-Jewish persecution. But from the inside, as Roma made amply clear, life for Jews was a "riddle." On the one hand, Jews, like Roma, understood that they did not belong in Polish society. They could see, and feel, that they were disfranchised. On the other hand, many, including Roma, were committed to the prospect of their social acceptance. Did they delude themselves, preferring an illusion to reality and believing, contrary to evidence, that, as critic JanBłoński noted"the future [for Polish Jews] would gradually become brighter, [when] what actually happened was exactly the opposite"? Perhaps. But I would rather address the riddle from the perspective of those who lived out history from within rather than from hindsight. Roma's recollections help us.

Roma's attachment to Poland and Polish culture; her preference for secular values and a humanitarian ethos was, above all, emotional and beyond anything that she could or, just as important, wanted to calculate. Notwithstanding the evidence, her love for her homeland was paramount. This surely led to some confusion: at one point she refers to the police as a symbol of protection; elsewhere, she describes its wanton brutality. What actually helps us to achieve some clarity is Roma's expression of "rage and sadness": She expected more from her beloved homeland. She commented on the complexity of romance after having previously been betrayed, but I feel that betrayal is the conceit of her story overall. Her commitment to the future was not a matter of self-delusion, something pathological. Even, if not especially, against the background of deterioration, it is the human condition, often with unexpected and sometimes with tragic consequences.

Roma survived. Her life after death granted life to Suzanna and her second generation. Suzanna talks about the third generation. We know that Roma, by writing this memoir, was thinking about posterity. We cannot know for sure, however, what the future looked like for her. Suzanna tells us that her mother died of a "broken heart." This memoir looks forward but is simultaneously burdened with heightened caution. For her, exceptional cruelty was the rule, not an exception. Aggressiveness, she believed, was endemic. She remembered when one of her boyfriends carried a gun "just in case he needed it." Incarceration by the authorities had nothing to do with the law or any other rational standard. It was plainly and crudely an instrument of power. The new order exalted might, not right. Suzanna, like the rest of us, inhabit this new order, knowing "what people are still capable of doing."

The future for Roma and other survivors of extreme violations was surely not as hopeful as she believed it was before the Holocaust. After the catastrophe, fellowship among former enemies, or what we sometimes refer to as meaningful reconciliation, would be an idle dream for her, if not impossible to imagine. Our world is post-rational. We need to understand Roma's unseen realities. After reading her memoir, we can now see that coexistence is a matter of power relations, not comity. Conflict is a normative state of human existence. We should enter unstable circumstances with this significant awareness so that, in defeating impracticable expectations, we are not surprised by and helpless before the relentless evidence. We should recognize human fellowship as a protean negotiation among insiders and outsiders. In light of this memoir, how can we regard human rights without acknowledging the reality of tribal intransigence? Yes, we now should know that, at heart, Jews are Jews and Poles are Poles. Common ground, as crucial as it is for civilization, is brittle. I believe we would be in a stronger position to achieve a more stable world once we fight for it with our eyes open.

Dennis B. Klein

Professor of HistoryDirector of Jewish Studies Program

Kean University,NJ, USA.

Introduction: Suzanna's Story

When the train started to pull away from the platformfromZiebice, my mother became hysterical. I heard a cry that was not human. To this day I have not heard a sound like it, but I understand now. My mother saw herself a deserter,leavingfrom her country for good;she knew she would never be returning to Poland.

After having lost so much, she was once again going to lose everything—including her identity. Inher years inAmerica,my mother'shomeland never stopped being part ofher veryessence. Herupbringingand heritage, her husband's grave, and the ghosts of her murdered family—thesethingswere always at the forefront of her mind,a piece of her forever left to linger in Poland.

Technically, our familyleft Poland by choice. In1968-1969,two yearsafter our departure,most of the remainingJews were forced out of Poland during an anti-Zionist campaign sponsored by the government and its Communist leader WladyslawGomulka. Witha political crisis and a bad economy threatening theCommunistsystem, history once again repeated itself and minorities became the scapegoats.The Jews before the war wereviewed asleft-wingSocialistsandCommunists; they were seen as responsible for bringing Communism to Poland and therefore blamed for its failure.

When Israel won thesix-day war in 1967 and the young JewsofPoland openly celebrated for the first time, theCommunistPartywas infuriated. Poland was ruled by Russia and Soviet tanks were found in the desert. Israel defeated not only Egypt but also Russia. The Polish party took'this Jewish pride'and made up a theory that in Poland, a'Zionist conspiracy'was growing against the government. Mass media and the secret police went on the offensive. Civil rights demonstrations held by students and'intellectuals'the government, turned into propaganda.Anunmistakableanti-Semitic undertone followed,and'intellectual'and'Jew'were words used interchangeably to degrade those who criticized the government. Thus began the targeting ofJewishstudents, professors, and professionals. The result was that most Polish Jews lost their jobs andabout 30,000 were forced out of Poland.Of the over3million Jewswho livedin Poland before the war,about100,000 Jews remainedat the end ofWorldWarII.By 1958,50,000 emigrated to Israeland other parts of the world, the restchose tostay,andtenyears later they were being forced to leave once again.By the timecommunism fell in Poland in 1989, only 5,000–10,000 Jews remained in the country, most chose to conceal their Jewish identity.

While traveling through Europe and Israel,I met so many Jewish Polish friends who never intended to leave Poland. They all told me the same story: They had no choice but to flee. They now were living abroad without theirelderlyparents, whochose tostay behind. Some were in mixed marriages, manyhad been able tohidetheirJewishidentity,or were hard-coreCommunists.

Communism, in theory, was incompatible with religion. The government in postwar Polandsaw the church as a counter-revolutionary organization, using its religious influence over the masses, against the dictatorship of the Communists. The Communist government's strategy of condemning the church,however,backfired and instead it drove the Polish people into the church.In 1978,Karol Wojtyla, the elected Polish Pope John Paul II,became an important supporter of Solidarnosc—the union that broughtdown Communism in Polandinthe late 1980s.Lech Walesa, the founder of Solidarnosc, creditsJohn PaulIIwithgivingPoles the courage to demand change.The pontiff told his countrymen:"Do not be afraid,let yourspirit descend and change the image of the land,this land."

The climate of anti-Semitismin Poland, of course,was present long before the spring of 1968. My mother lived through the Great Depression of the early 1930s; she witnessed the tension between the working class and the capitalists,as well as the deterioration between Polish nationals and Jews. The state of affairs between Jews and Polesbegan its sharpdecline after the death of GeneralJozef Piłsudskiin 1935 and it continued until the German invasion on September 1, 1939.

My parents, and many other Jewish survivors who had remained inRussian territoriesthrough the war,chose toreturn toPoland and raise families. But life in Poland for Jewish families proved to be challenging.Inthe summer of 1946,after living with Russia's communism during the six years of war, my parents refused to join theCommunist Party. Our family was Jewish in an overwhelmingly Christian country andbyrefusingto join theCommunistParty, we paid a heavy price.We were excluded from the social structure reserved for party members.My mother could not find a job.My father,afterbattlingfrequent bouts ofpneumoniain Russia during the war,without any medicaltreatment,wasdeclaredterminally illwith tuberculosisin1951.He wasgivenasmall disability pension. In order to sustain us,my parentswere forced to operate a smallprivatebusinessthatwasstrictly regulated by the Communists.This small business,however,couldnot support a family offour; they had to find other creative ways totradeandbreaktherestrictiverules.My parents andthe surviving Jewish communitynot onlywere persecuted by the governmentthatcontrolled the freedom to speak, to think,andto express ones ideas,butthey werealsoencircledbythePolish CatholicChurchwiththeirunchanged-for-centuriesattitudestowardJudaism. Anti-Semitismin Poland, sanctioned by theChurch,never went away.After the war the Church continueditsharmful and hostilepositiontoward Judaism and Jews that it had for centuries.The position of the Polish Church was not atypical;it was the same as the viewpoint held by the Vatican and other national churches.Starting in 1978, Pope John Paul II went on a missionto significantlyimprovethe Catholic Church's relations with Judaism. He was the first pope to visit the Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland, wherePolish Jews had perished during the Nazi occupation in World War II.He issued"We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah,"his thoughts on the Holocaust. He became the first pope known to visit the Great Synagogue of Rome and he established formal diplomatic relations with the State of Israel. He hosted a Concert to Commemorate the Holocaust, first-ever Vatican event dedicated to the memory of the6million Jews murdered in World War II. John PaulII visited Yad Vashem, the national Holocaust memorial in Israel, and he made history by touching the holiest of sites in Judaism, the Western Wall in Jerusalem where he placed a letterwith a prayer askingfor forgiveness for the actions against Jews.

***

Myfather died fifteen years after returning home fromtheRussian territories.Whenhedied,my mother went into despair. Theyhad been togetherfor twenty years. My mothersuffered a severe attack of eczema that covered her face with sores.Even in those days it was known that her ailment was stressrelated.My mother, my sister,and Ihad no other family in Poland;my mother had one sister who survived the war, who ended up in America by a lucky chain of events. Together they survivedsix arduous years inRussia only to be separated on their trip back to Poland after the war. Twenty years would go by before they would see each other again.

When my father died, mymother chose to be reunited with her sister Pola. Witha strictquota system in place, itwouldtake anotherfour years before mymother,myseventeen-year-oldsisterBluma,and I would leave Poland. I was thirteen years old. Till the last day my mother was uncertain about emigrating. She knew she was going an ocean away, never to return. Educated in the Polish public school shelearned at an early age to bea patriot.She would be abandoning Bund's ideology, the duty of keeping watch over Jewish heritage on Polish soil.Bund's ideology taught her that Jews could coexist with other nationals anywhere in Europe while preserving their Jewish identity and heritage. Poland was her homeland and that of her ancestors. Poland was where she felt at home, and where she felt she belonged; she survived Russia with only one hope, to return to Warsaw.In leaving,she would be forsaking the ghosts of her murdered familyand abandoning the promise she made to her husbandthat she wouldfight for his dreamofreclaiminghisancestors'property.

After the war, too,my motherforever lived with the hope that a member of her extended family would be found and walk through the door of our home.

When my sister and I tried to console her on that train leaving Poland, she did not hear us, and it was only later in my life that I understood how my mother felt back then.

***

When I first read Elie Wiesel's writings,I realizedthat the psychological impact of the Holocaust on survivors wasreal and it was enormous.Forthe first time,I understood the importance of my mother's stories that she passed on to me when I was a child, and I persuaded her to write about her tragic and triumphant life. My mother hesitated at first, but as I persevered, she agreed. I understand now thatformy mother toreenter the world she suppressed for so longwas agreat risk to her safety and sanity.But for the sake of truth,she relived terror, hunger,and pain. She bravelyrememberedthe family she abandoned in Warsaw and brought them back to life. She confronted the memory ofimpossible hardship,surviving in Russia,andadded hervoice toageneration that was silenced by Hitler.

In writing down herstory,my mother restored herself and left me with a better understanding of the second generation.With her heartbreaking childhood, her will to survive in Russia, a resolve to pick up the pieces after the war,and the courage to start a new life in America,she leaves behinda legacy of extraordinary spirit, perseverance,and hope for future generations—for my daughters andforme.Until theveryend of her life, she tried to make sense of the horrific time she endured. All she could do was to write down her personal account of what happened. It was howmy motherwasfinallyable to emerge from her exile and give herself permission to heal.

My motherunderstood the importance of history and of remembering, not justinregard to the Holocaust, butalsocommemorating the vibrant Jewish culture in Poland shehad beenpart of, and the legacy they leftbehind inEastern Europe. She wrote her story in Polish. My huge regretisthat I did not get to work on her memoir while she was still alive. As adults, we never had thechancetotake thisjourneytogetherand emerge from her trauma.

* * *

In the early hours of myfifty-fifthbirthday,I received a call that my eighty-nine-year-old mother had died. She was not well for the last months of her life. For the past couple of years my mother lived at the Jewish Home for the Aging,fifteen minutes away from me, and I had gone to see her almost every day.We had made plans to spend that morning together.

In the Jewish tradition,it is customary to mourn the loss of a parent by staying home for a period of a week.I satShiva [1]forafullmonth,flooded with memories of my childhood in Poland, a time when I lived in constant fear of losing my mother.Survivors of the Holocaust,my parentshad transmitted this fear of abandonment tomy sister and meat birth. Now, my childhood fear had been realized. In losing my mother, I lost my only link to myrootsand to the family I never knew.In Poland our tinyfamily of fourwasalone,but with my mother's death, in an instant,allconnectionstoourancestorsweresevered forever;my sister andIhad become orphans.

Six years before she died,my mother made herverylast trip to be close to me,movingfromNew Yorkto LosAngeleswhere I lived at the time. In 2006, the last year of her life, I had a daughter away in college and anotherstillin high school; Ifelt fortunate that I wasable to see my motherevery day. Wewouldpass the time talking about her life. Her memory was sound and her blue eyes camealwaysalive with the recollections. Going back in time broughtmy mother bothcomfort and torment.

It was obviousto me thatthere had never been any closure for my mother. She seemed forever bewildered by the events she was forced to live through. Robbed of a life and a family, her anguish increased as she aged. She died of a broken heart, of never knowing what happened to the family she loved. The suffering she endured during the six years she was in Russia became meaningless once she discovered what had happened to the Jewish community of Warsaw.

She was forever haunted by horrific memories.At night, in her dreams,shewas alwaysrunningaway from theGermans andfromthebombs falling over Warsaw.Herreoccurring nightmares and screaming left me feeling helpless and frightened.During the waking hours shetormentedherselfwithrecollections of the family she left behind in Warsaw. And of the horrible fate that awaited them.She sawher brother Adek, sisters Sala and Anja,theirwife,husbands,and theirfiveyoung childrenstarved and frozento deathin the streets of the WarsawGhetto.She recalledher large extendedfamily on her mother's side, heruncle Motel and auntHadassa with all their children, her cousins.She saw them in the cattle cars that took them to the Treblinka death camp. She saw her brotherSevek,sent to the front lines, a soldierwithout a gun,toserve asa human shield,cold and barefoot,to bekilledbyeitherRussianor Germanbulletsin the city of Astrakhan.

My mother never forgave herself for leavingPolandto save her own life and abandoning her loved ones to the horrible deaths that followed.She never stopped mourning.Fixed in my memory are thewords she repeated:"Mylife was sparedinRussiabutmyfamily diedin PolandbecauseofHitler."

My mother sufferedunfathomable losses.My fathersufferedtoo. Overtime,I came to realizethat it isimpossible to recover from such a tragedy. After the war,my parentsdid their best tocarryon with their lives and raise their family, but the Holocaust'sinevitableaftermath played out on daily basis.

My mother was never able to understand or accept how the Holocaust was allowed to happen. Howcouldthe civilized world stand by and watch6million of her brothers and sisters being murdered? The years of war changed her; she emerged as ahardenedwoman no longerable to believein God.But surviving the poverty of her childhood and teenage yearsalsomade her strong, and with this strength shesomehowmanaged to survive the war. Shemade it throughthe Holocaust scarred and shattered, refusing to permit herself to experience happiness or joy. I believe this is howmy motherpaid respect and honoredthedeadin herfamily. She trusted no one, never let her guard down, and chose seclusion in place of connecting to others.Consciously and unconsciously, her trauma was transmitted to the next generation, her daughters.The trauma of loss, the disconnection from family and community has influenced howwe thechildren of survivors live our lives.We, too, havebuilt a wall to protect us from the traumatic home lives we grew up in.Even as a small child I found a way to protect myself when Iimaginedmy life wasin dangerby withdrawing and retreating into my world. I would exile myself and build wallsof protectionaround me. I found this protection under ourlargekitchen table, covered by a crisp,white tablecloth that reachedtothe floor. I rememberhavingan abnormal fear of peoplewhocame to our homeoften.I hid in my sanctuaryandwould not come out untilthey departedandthe worldwassafe again. Under the table I feltsafe andprotected;no harmcouldcome tome there.As a child in postwar Poland, countless times Ihad to watchour friends and neighbors pack their belongingsand leave. From those early experiences, I learned that friendships were short-lived and that nothing around us was permanent.In that respect our life after the war wasoddlysimilar tomy mother's description oflifeduring the war.

As an adultI was forever torn between letting go and staying connected.Oftenmy mother's gloom was too intense for me, but I continually found myself being pulled back into her worlddespite myself. My conscience would not allow anything else. And with my mother's death, memories became sacred.

* * *

On the day my mother died, I opened the small white box containing aged pages torn from various notebooksshe had kept over the years.Tears stained some of the pages.This was amemoir she hadfirstbrought to me six years earlier. In thin, shaky handwriting she recalledheart-searing memories that began with being born Jewish in Warsaw in 1917.

Her rushed handwriting looked as if she was afraid she might forget something or run out of time. Reading my mother's pages took me back to theoften-toldstories I heard as a child.These storieshadhaunted my childhood, givingme nightmares of my own,butnow I understood their purpose;it was her way to insure that her doomed generation be remembered for generations to come. She guarded this box as if it wasa prizedpossession. She handed it to me right after wegothome from the airport,the dayshe arrived in Los Angeles.On two separate occasions my mother and I sat down to work on the pages together, but other things got in the way.Webecame fluent in English but never abandoned our native tongue. Now,asIsatalone,looking downatmy mother'shandwriting,so familiar to me,absorbingher hauntingwords, Ifound myself beingtransportedback to my childhood in Poland. I was inundated with flashbacksof the timesshe and Isat together, my motherdescribingthe life sheoncehadthat was forever destroyed.

* * *

My daughterhas convinced me to write about my life.Painful though it will be, I have decided to do this; not so much to preserve my story, but so that my brothers and sisters—and myentire lostgeneration—will not have perished with their stories untold.

I risk feeling again my stomach gnawed by constant hunger, the clutch of terror in my chest at seeing German planes over Warsaw,and hearing the explosions of bombs, the tormented sleep on an open field with one thin blanket between me and the sky. How can I describe the despair and loss of an entire family, the nonstop guilt, the haunting nightmares, and the chill that seeped into my bones and never quite left?

Still, I know that I have an obligation to bear witness. It was beshert—meant to be—that I survived to write what I remember.

Roma

* * *

My mother's handwriting, her wordsmade me feel close toher. As I started to read her story she came to life on the pages—I knew instantly that I had a responsibility to translate and retell her story.

I thought of the Campo dei FioriIn Warsaw by the sky-carouselOne clear spring eveningTo the strains of a carnival tune.The bright melody drownedThe salvos from the ghetto wall,And couples were flyingHigh in the cloudless sky.

―Czesław Miłosz

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!