9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

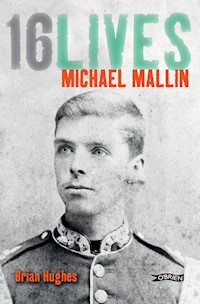

Executed in Kilmainham Gaol on 8 May 1916, Michael Mallin had commanded a garrison of rebels in St Stephen's Green and the College of Surgeons during Easter Week. He was Chief-of-Staff and second-in-command to James Connolly in the Irish Citizen Army. Born in a tenement in Dublin in 1874, he joined the British army aged fourteen as a drummer. He then worked as a silk weaver and became an active trade unionist and secretary of the Silk Weavers' Union. A devout Catholic, a temperance advocate, father of four young children and husband of a pregnant wife when executed – what brought such a man, with so much to lose, to wage war against the British in 1916?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

The16LIVESseries

JAMES CONNOLLY Lorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLIN Brian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETT Honor O Brolchain

ROGER CASEMENT Angus Mitchell

THOMAS CLARKE Laura Walsh

EDWARD DALY Helen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTON John Gibney

SEÁN MACDIARMADA Brian Feeney

ÉAMONN CEANNT Mary Gallagher

JOHN MACBRIDE William Henry

WILLIE PEARSE Roisín Ní Ghairbhí

THOMAS MACDONAGH T Ryle Dwyer

THOMAS KENT Meda Ryan

CON COLBERT John O’Callaghan

MICHAEL O’HANRAHAN Conor Kostick

PATRICK PEARSE Ruán O’Donnell

BRIAN HUGHES

Brian Hughes was born in Dublin and studied in NUI Maynooth where he graduated with a BA in History and English. He received an M.Phil in Modern Irish History from Trinity College, Dublin, where he wrote a dissertation on Michael Mallin. He is currently working on a PhD thesis on the Irish revolution.

LORCAN COLLINS - SERIES EDITOR

Lorcan Collins was born and raised in Dublin. A lifelong interest in Irish history led to the foundation of his hugely popular 1916 Walking Tour in 1996. He co-authored The Easter Rising (O’Brien Press, 2000) with Conor Kostick. Lorcan regularly lectures on Easter 1916 in the United States. He is also a regular contributor to radio, television and historical journals. 16 Lives is Lorcan’s concept and he is co-editor of the series.

DR RUÁN O’DONNELL - SERIES EDITOR

Dr Ruán O’Donnell is a Senior Lecturer at the History Department, University of Limerick. A graduate of University College Dublin and the Australian National University, O’Donnell has published extensively on Irish republicanism. Titles include Robert Emmet and the Rising of 1803, The Impact of 1916 (editor) and Special Category, The IRA in English Prisons 1968-1978. He is a Director of the Irish Manuscript Commission and a frequent contributor to the national and international media on the subject of Irish revolutionary history.

DEDICATION

To my parents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project started life in 2007 as a dissertation for an M.Phil in Modern Irish History in Trinity College, Dublin. That dissertation was completed in 2008 under the supervision of Dr Anne Dolan. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Dr Dolan who was, and continues to be, a source of advice, encouragement and inspiration to my research.

My name would not be on this book were it not for Lorcan Collins, creator and co-editor of the Sixteen Lives series. Lorcan has shown a great amount of faith in me and for that I am eternally grateful. As well as shepherding me along on this project, Lorcan also sourced many of the brilliant photographs that are reproduced in this book.

At the O’Brien Press I am indebted to Michael O’Brien for the opportunity. I am grateful to my editor Ide Ní Laoghaire and designer Emma Byrne whose expertise and professionalism is evident throughout the book.

A number of friends read extracts and chapters at various stages of the book’s life and I am most grateful to them all: Conor Mackey, Fergal O’Leary, Ian Priestley, Rita Murray, Jürgen Karwig and Amy Branagan. James Buckley has proofread, provided feedback and a keen and interested ear since I began writing about Michael Mallin and deserves special thanks. Fr Joseph Mallin, Michael Mallin’s son, has been an inspiration and provided invaluable information in his many wonderful letters. Other relatives of Mallin – Niall O Callanain, Una Ui Cheallanain and Sean Tapley – have also been very kind in dealing with my questions. I thank Francis Devine for information and membership numbers for the Silk Weavers’ Union, and Denis Condon on Dublin cinema.

I would like to thank the archivists and staff at the National Library of Ireland, National Archives, Dublin, the Allen Library and Trinity College Library for their help during my research. I wish to pay particular thanks to those who helped source and provided permission for reproduction of photographs, in particular Niall Bergin and Anne-Marie Ryan of the Kilmainham Gaol museum and June Shannon and Mary O’Doherty of the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland.

Finally, I wish to place on record my deep gratitude to my parents, Seamus and Jacinta, who have been fully supportive of everything I have done or tried to do. This book is for them.

16LIVES Timeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867,February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870,May. Home Rule movement, founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners.

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September. Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07. Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Prime minister Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU), calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eoin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joins the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm. The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm. The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork harbour.

22 April, 9.30am. The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eoin MacNeill as Chief-of-Staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVESMAP

16LIVES - Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 Lives conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire to set Ireland on the road to national freedom united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

The 16 Lives biographies are meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion. Each book can be read as an individual volume but together they make a highly collectable series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell, 16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Chapter One

• • • • • •

1874 – 1889

Family and Early Life

In the months after the execution of the leaders of the 1916 Rising the Catholic Bulletin wrote a series of articles entitled ‘Events of Easter Week’, describing Michael Mallin as ‘Commandant Stephen’s Green Command … a silk weaver and musician, a splendid type of the Dublin tradesman, a credit to the city which cradled him close on forty years ago.’1 This was very much the conception of Mallin in the years following his execution. A contemporary pamphlet on the leaders of the Rising wrote of Mallin: ‘Nor must we forget Michael Mallin … a silk weaver by profession, a musician and an active temperance advocate, he was one of the most sanguine of all the Company Commanders.’2

Of the sixteen men executed for their role in the planning and execution of the rebellion, Michael Mallin is among the lesser known. Virtually nothing has been written about his life before October 1914; he appears in literature about the Rising only after he becomes James Connolly’s Chief-of-Staff. Perhaps Michael Mallin has been overshadowed in history by two figures: James Connolly, the only man higher in rank than Mallin in the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), and Countess Constance Markievicz, second-in-command to Mallin during Easter Week 1916. Mallin has almost become ‘sandwiched’ between these two iconic figures and his own significance neglected as a result.

Michael Thomas Mallin was born into a working-class Dublin family on 1 December 1874 in Ward’s Hill in the oldest part of the city, the Liberties. Mallin’s eldest son has recorded that he often signed his name as ‘M.C. Mallin’, the ‘C’ standing for Christopher and probably a Confirmation name.3 He was baptised on 6 December in the church of St Nicholas of Myra on Francis Street.

Mallin’s father, John, had grown up in the home of his grandfather, also named Michael, at City Quay; his grandfather made parts for sailing ships. John was the son of another John Mallin and Mary Mangan (said to be a daughter or cousin of the poet James Clarence Mangan), and he had a brother, Michael, who died as a young child. John’s mother, Mary, disappeared in strange circumstances – she went missing one stormy night and it was thought that a strong wind had swept her into the river Liffey; her body was never found. Soon afterwards, John’s father emigrated to Australia, leaving his son with his own father. He was not heard from again and it was rumoured that he was murdered in Australia.

John Mallin had married Sarah Dowling around 1874 and Michael Mallin was born that year. Mallin’s mother, who, unlike the rest of the family, was unable to read and write, had worked in a silk factory in Macclesfield, England, but had lost her job when she expressed sympathy for the ‘Manchester Martyrs’ – in November 1867 William Allen, Michael Larkin and William O’Brien were hanged for their role in an attack on a police van in Manchester in September of that year, an attempt to free two prisoners, during which an unarmed policeman was killed. Sarah Mallin had apparently witnessed the attack on the police van. The execution of the ‘Manchester Martyrs’ provoked a swell of sympathy for the movement for independence in Ireland. It is not clear if Mallin’s mother was sympathetic to the cause prior to events in Manchester (she had family in the British army) or if she was moved by what she had seen, but she does seem to have shown support for the independence movement in later life. Returning to Ireland, she worked in Dublin as a silk winder.

Mallin’s mother came from a family steeped in the traditions and culture of the British army, even if she did not share this tendency. Two of her brothers were in the British army, both serving with the Royal Scots Fusiliers. A third, Bartholomew Dowling, had decided to join the priesthood, but instead he met a girl from Connemara on a trip to England and chose to leave his training and get married. At that time it was seen as a source of great shame not to finish one’s training as a priest, and that he left to get married only added to the disgrace. To escape this, he decided to sever relations with friends and family and move to America. Having not heard from her brother for a period, Sarah Mallin decided to go to America to find him; she took her young son, Michael, with her. They seem to have stayed in a house in New Bedford, Massachusetts, for a short period until the missing brother was located.4 Little else is known of this trip.

At the time of Michael’s birth in 1874 the family was living in a tenement building at 1 Ward’s Hill, the Liberties having the highest concentration of low-value housing in the city. In the 1870s Ward’s Hill was characterised by decayed eighteenth-century buildings; fine Georgian houses that had once housed the most affluent members of Dublin’s population had been taken over by unscrupulous landlords whose aim was to squeeze every penny of rent possible from these buildings. Whole families occupied single rooms, heating and sanitation was severely lacking and privacy was almost non-existent. At their worst, Dublin’s slums were among the most appalling in Europe. Infant mortality was high: of eleven children born to John and Sarah Mallin, six survived to adulthood. Of the surviving children, Michael was the eldest of four brothers, Thomas (Tom), John and Bartholomew (Bart) and two sisters, Mary (May) and Catherine (Kate or Katie).

Not all who occupied tenement buildings were completely impoverished: in fact, Mallin’s father, John Mallin, was a skilled boatwright and carpenter and his father, Michael’s grandfather, had a boat-building yard in Dublin, which had been in the family for five generations. The Mallins would have enjoyed a more substantial income than many of those around them, but the poor living conditions made raising a large family difficult.

Mallin’s eldest brother, Tom, worked as a carpenter, while brothers John and Bart worked as silk weavers, sisters Mary and Catherine as a biscuit packer and vest maker respectively.5 According to Tom, Mallin’s father was a ‘strong nationalist and he and Michael had many a political argument’.6 Mallin’s youngest son, Joseph, has described his own recollections of his father’s family:

Uncle Tom was more outgoing than John or Bart. John’s family and his wife were extremely pleasant – no histrionics. … [aunt] Kate, always seemingly gently amused when talking about the family & others. She was amusing about my grandfather [John Mallin]. He disliked any coarse language and if it started would remark he did not like such talk and would leave the company. [William] Partridge noticed that trait in my father.7

The family lived in a number of locations around the Liberties over the years. It was not uncommon for Dublin families at this time to move around the city, often within relatively close proximity, as their financial conditions improved or worsened. In 1889 Mallin’s family was living in Marlborough Street and by 1901 they had moved to a residence in Cuffe Street where they would remain for at least the next decade. Little is known about Michael’s education but he probably attended the national school in Denmark Street, near the family’s home. Like most from his social background, Michael’s formal education was brief and basic and he left school in his early teens.

In 1889, shy of his fifteenth birthday, he was persuaded to join the British army by an aunt during a visit to the Curragh in County Kildare. Michael’s uncle, James Dowling, had served with the Royal Scots Fusiliers for a number of years in India and was then employed as a Pay Sergeant in the Curragh. Michael seems to have been close to his uncle, often spending summer holidays with him. It was during one of these holidays that Michael first became aware of the Royal Scots Fusiliers. The regiment’s band had made a great impression on the young Michael and this is what prompted him to enlist. On hearing that her son had joined the army, Sarah Mallin was worried and angry with him for doing so; he reassured her that it was the musical band that he had joined.8 Michael Mallin joined the 21st Royal Scots Fusiliers in Birr on 21 October 1889 as a drummer boy, signing up for twelve years’ service. Surviving records from his enlistment give a physical description of him as a boy approaching fifteen: he was 4 feet 5 inches in height (he was never to be a tall man), 64lbs with a ‘fresh’ complexion, grey eyes and brown hair. His regimental number was S.F. 2723.9

Notes

1 ‘Events of Easter Week’, Catholic Bulletin, Vol. VI, No. VII (July 1916), p398.

2Sinn Féin Leaders of 1916, Dublin, 1917.

3Inniu, 30 Oct. 1966.

4 Mallin family 1901 and 1911 census returns (National Archives of Ireland); Bureau of Military History Witness Statement (BMH WS) 382 (Thomas Mallin).

5 Ibid.

6 Fr Joseph Mallin, S.J., to the author, 13 Nov. 2009.

7Inniu, 30 Oct. 1966.

8Inniu, 30 Oct. 1966.

9 BMH WS 382 (Thomas Mallin); Account book of Michael Mallin, Royal Scots Fusiliers (Kilmainham Gaol Archive); Michael Mallin’s British army record (National Archives, Kew: WO/97).

Chapter Two

• • • • • •

1889 – 1902

British Army Career

When Michael Mallin joined the Royal Scots Fusiliers the regiment was on an extended period of home service. Beginning in 1881, fifteen years were spent stationed in Portland (England), Fermoy (County Cork), Birr (County Offaly), Dublin, Glasgow (Scotland) and Aldershot (England). There is little of note for this period in the regimental diary beyond ‘annual inspections, and the invariably flattering reports’, the Duke of Cambridge apparently declaring that ‘such manoeuvring was seldom seen nowadays’.1 The first battalion, of which Mallin was part, formed a guard for Queen Victoria at Balmoral in 1891.2

Following just over eighteen months of ‘boy’ service, Mallin was given the rank of ‘drummer’ on 1 June 1891.3 Traditionally, the role of a drummer in war was to provide a steady beat for the soldiers to march to and to raise troop morale in battle. The rhythm of the drums could also be used by soldiers to keep time when firing or reloading rifles. Though referred to as ‘drummers’, their duties would often be performed with flutes or bugles. During peacetime the role of the drummer was usually ceremonial: playing at parades, reviews and other events. As part of his training, Mallin learned the flute, violin, studied music theory and obtained a 3rd class certification on 13 March 1893.4 Aside from their musical requirements, band members also received much of the same basic training as regular members of the infantry. In 1894 Mallin earned the grade of ‘marksman’ for the first time and was to obtain this grade – first class or second class marksman – each year until his discharge.5

Mallin seems to have been a disciplined soldier. Although he was never promoted beyond the grade of drummer, he earned increases through ‘Good Conduct Pay’ on three occasions throughout his service: 1d (one penny) following two years’ service in 1891; 2d following six years’ service in 1895; 3d following twelve in 1901.6 He was also, apparently, a useful lightweight boxer and won a couple of medals for sport.7

In 1896 the Royal Scots Fusiliers were sent to India, then part of the British empire, and Mallin began what amounted to a stay of over six years there on 24 September. For the first eight months the regiment occupied various stations in the Punjab, north India. As noted by John Buchan, who published a history of the regiment in 1925, at this point the Scots Fusiliers were ‘very near to active service, for the mutterings of trouble were beginning in the frontier hills.’ Mallin’s first, and only, period of active service followed: the ‘Tirah campaign’, often referred to in contemporary accounts as the ‘Tirah expedition’. This campaign lasted about two years and consisted of a series of encounters with various native tribes.

The Tirah region is in modern-day Pakistan, but in the nineteenth century was part of British India. Trouble first erupted in the Khyber Pass, a mountain pass leading to Afghanistan, which formed a significant part of the lucrative ‘Silk Road’ trade route. From the early 1880s the Afridi (a collection of Indian tribes) had guarded the Khyber Pass in return for a subsidy from the British India Government. The government had formed a number of defensive posts in the area manned by units of Afridi. In July and August 1897 there was a general uprising of these tribes. In his work on the regiment, John Buchan linked this uprising to the ‘wide resurgence of Moslem pride which followed Turkey’s easy victory over Greece.’ The Afridi destroyed the posts guarded by their own countrymen along the Khyber Pass. Meanwhile, in the Swat and Tochi valleys to the north-east of the pass, the Mohmand tribe had risen against the British. By October, the Mohmands had been suppressed by two British divisions moving from Makaland and Pashawur respectively, with the loss of nearly a quarter of the force. Then the Afridi tribes attacked the British forts at Samana Range, further south. Sir William Lockhart was tasked with assembling the Tirah Expeditionary Force to deal with this more troubling outbreak. The native tribes used their knowledge of the landscape to inflict an often devastating guerrilla campaign on the regular troops. John Buchan has described some of the difficulties facing the army in quelling the local tribes:

Between them the Afridis and the Orakzais could bring more than 40,000 men into the field – men armed not with jezails and old muzzle-loaders, but with [more modern and efficient] Martini-Henrys or stolen Lee-Metfords. The terrain, too, was most intricate and difficult – one of which Wellington’s words in the Pensinsula were true: ‘If you make war in that country with a large army, you starve; and if you go into it with a small one, you get beaten.8

By December 1899, however, the local tribes had been sufficiently suppressed to end ‘this sharp little campaign’.9 Mallin was awarded with the India medal (1895), with the ‘Punjab frontier’ clasp (1897-98) and the ‘Tirah’ clasp (1897-98).10 Following the end of the Tirah campaign, the Royal Scots Fusiliers remained in India, stationed in various towns and cities in the north of the country (including Landi Khotal, Peshawur, Cherat, Chakrata, Allahabad, Bareilly, Amritsar and Jubbulpore) with no ‘break in the monotony of its life.’11Although the British Army was still active in India the Scots Fusiliers were not called into action.

While on leave in Ireland, some time before leaving for India, Mallin joined a friend of the Hickey family in visiting their home, between Lucan and Chapelizod in Dublin. There he met Patrick Hickey’s young daughter, Agnes. Mr Hickey was originally far from happy to have a British soldier visiting his house. He was an old Fenian and had been exiled for his role in the 1867 uprising. Soon, however, they became close friends. From the end of 1894 until his return from India in 1902, Mallin kept up a regular correspondence with Agnes, and they became engaged to be married. Letters that Mallin wrote have survived and offer a rare and tantalising glimpse of Mallin’s time in India, his attitudes to the war he was asked to fight and the flag under which he fought.12 He writes in an unpunctuated, continuous-flow style, with regular misspellings.

For most of the ‘Tirah campaign’ (1897-98) Mallin was stationed in Sialkot. He seems to have made little reference to his orders or the fighting itself in his correspondence with Agnes, except in one early letter, sent from Sialkot in November 1897, in which he gave a detailed description of a battle at the Ublan Pass, just outside Kohat in modern-day Pakistan. Mallin was part of a force that was given orders to ‘clear the enemy off the hills about six miles away’. He mentions that he was with ‘H’ company as they were short of buglers, suggesting that he fulfilled the traditional role of a drummer or bugler during the fighting. This is the only mention of his own duties in the field in the letters. He had some infantry training, including in musketry, but it is not clear if he ever fired a rifle in battle. For this engagement the men set off at three thirty in the morning with only ‘a pint of tea one gill of rum in it and one biscute [sic] we had to march six miles and fight on that.’ They spent much of the time walking in ‘the bed of a river … the water was past [sic] our knees very near the whole time.’ Mallin described the scene when they reached the enemy:

the Artillery set the ball rolling you should have heard the shouting of the enemy as soon as the shells burst amongst them as soon as the Artillery had done with them we moved to the attack the enemy rolling big stones on top of us one of them struck two native soldiers killed one and broke the other poor fellows [sic] legs.

Three of the native soldiers were killed and five wounded. They reached the top of the hill, but the enemy had moved to another hill and showered them with bullets, forcing a retreat. However, when they retired from the hill, the enemy ‘swarmed up it again’ and they had to fight again. This time the artillery could not be used as the soldiers were too near the target. Mallin related how: