15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

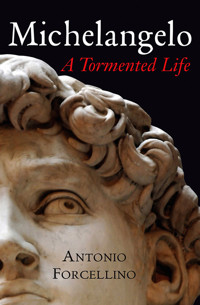

This major new biography recounts the extraordinary life of one of the most creative figures in Western culture, weaving together the multiple threads of Michelangelo's life and times with a brilliant analysis of his greatest works. The author retraces Michelangelo's journey from Rome to Florence, explores his changing religious views and examines the complicated politics of patronage in Renaissance Italy. The psychological portrait of Michelangelo is constantly foregrounded, depicting with great conviction a tormented man, solitary and avaricious, burdened with repressed homosexuality and a surplus of creative enthusiasm. Michelangelo's acts of self-representation and his pivotal role in constructing his own myth are compellingly unveiled. Antonio Forcellino is one of the world's leading authorities on Michelangelo and an expert art historian and restorer. He has been involved in the restoration of numerous masterpieces, including Michelangelo's Moses. He combines his firsthand knowledge of Michelangelo's work with a lively literary style to draw the reader into the very heart of Michelangelo's genius.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 709

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Front Matter

Introduction

Notes

Chapter 1 Childhood

1 The Back of Beyond

2 Magnificent and Heartless Florence

3 A Restive Apprentice

4 The Garden of Wonders

5 The Final Salute to Donatello

Notes

Chapter 2 Youthful genius

1 Panic Attacks

2 The Story of a Counterfeit that Ends Well

3 The Artistic Treadmill

4 A David Worthy of the Republic

5 Michelangelo’s Workshop

6 The Struggle for Artistic Pre - Eminence

Notes

Chapter 3 At the court of Julius II

1 A Warrior Pope

2 A Commissioner with Endless Patience

3 The Adventure of the Ceiling

4 The Crisis

5 Paintbrushes

6 The Triumph and the Legend

Notes

Chapter 4 Back and forth between Rome and Florence

1 In The Name of the Father

2 The Peaceful Years

3 Dangerous Ambitions

4 The Reconciliation

5 Failure

6 A Prisoner of Destiny

Notes

Chapter 5 At the beck and call of the Medici

1 A Disputed Artist

2 A Disastrous Policy

3 In Defence of the Republic

4 The Glory of the Medici

Notes

Chapter 6 Michelangelo’s glasses

1 Still Young at Heart

2 Heaven and Earth

3 Vittoria’s Gift

4 A Fervid Heresy

5 The New Style

6 The Two Moses

Notes

Chapter 7 The Pauline Chapel

1 Problems with the Domestic Accounts

2 The Emotive Power of Light

3 The Conversion of Saint Paul

4 Dangerous Images

5 Saint Peter’s Expression

6 Censorship Casts its Shadow

Notes

Chapter 8 No more illusions

1 Devotional Subjects

2 The Roman Family

3 Marriage Proposals

4 Building Saint Peter’s

5 Outliving his Friends

6 Paul IV, The Enemy

7 The Destruction of the Pietà

Notes

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Figure 1.1

Francesco Rosselli, Veduta della catena [View of the Mountain Chain]. Detail of …

Figure 1.2

The Medici family, from Cosimo the Elder to Cosimo I

List of Plates

Chapter 4

Plate 1

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Battle of the Centaurs, Casa Buonarroti, Florence

Plate 2

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Madonna della Scala. Casa Buonarroti, Florence

Plate 3

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Angel Holding a Candelabrum. San Domenico, Bologna

Plate 4

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Bacchus, Bargello National Museum, Florence

Plate 5

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Saint Matthew, The Academy, Florence

Plate 6

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Pietà, Saint Peter’s, Rome

Plate 7

Michelangelo Buonarroti, David, The Academy, Florence

Plate 8

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Madonna of Bruges, Nôtre-Dame, Bruges

Plate 9

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Pitti Tondo, Bargello National Museum, Florence

Plate 10

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Taddei Tondo, Royal Academy, London

Plate 11

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Dying Slave, Louvre, Paris

Plate 12

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rebel Slave, Louvre, Paris

Plate 13

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Christ Carrying the Cross, Santa Maria sopra Minerva, R…

Plate 14

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Genius of Victory, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

Plate 15

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Prisoner known as Atlas, The Academy, Florence

Plate 16

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Prisoner known as Youth, The Academy, Florence

Plate 17

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Prisoner Who Reawakens, The Academy, Florence

Plate 18

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Prisoner known as The Bearded Slave, The Academy, Flore…

Plate 19

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici, Sagrestia Nuova, San Loren…

Plate 20

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Allegories of Night and Day. Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medic…

Plate 21

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Allegories of Dusk and Dawn. Tomb of Lorenzo de’ Medici…

Plate 22

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Medici Madonna, Tomb of Lorenzo de’ Medici, Sagrestia N…

Plate 23

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Fall of Phaeton. Academy, Venice

Plate 24

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Rape of Ganymede. Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, MA

Plate 25

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Tomb of Julius II, Church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rom…

Plate 26

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Contemplative Life, Tomb of Julius II, Church of San Pi…

Plate 27

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Active Life, Tomb of Julius II, Church of San Pietro in…

Plate 28

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Moses, Tomb of Julius II, Church of San Pietro in Vinco…

Plate 29

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Crucifixion for Vittoria Colonna

Plate 30

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Pietà for Vittoria Colonna

Plate 31

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Pietà Bandini

Chapter 6

Plate 1

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Doni Tondo, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Plate 2

Sistine Chapel interior, Vatican Palaces, Rome

Plate 3

Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Vatican Palaces, Rome

Plate 4

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Universal Flood, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Palaces, R…

Plate 5

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Fall of Man, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Palaces, Rome

Plate 6

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Last Judgement, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Palaces, Ro…

Plate 7

Michelangelo Buonarroti, detail of Christ in judgement surrounded by saints, The…

Plate 8

Michelangelo Buonarroti, detail of the devils, The Last Judgement, Sistine Chape…

Plate 9

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Conversion of Saint Paul (detail), Pauline Chapel, …

Plate 10

Michelangelo Buonarroti, The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, Pauline Chapel, Vatica…

Plate 11

Filippino Lippi, The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, Brancacci Chapel, Florence

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

MICHELANGELO

A TORMENTED LIFE

ANTONIO FORCELLINO

TRANSLATED BY ALLAN CAMERON

polity

First published in Italian as Michelangelo: Una vita inquieta © Gius. Laterza & Figli, 2005

This English edition © Polity Press, 2009

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK.

Polity Press350 Main StreetMalden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-4005-1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

With the support of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The translation of this work has been funded by SEPS SEGRETARIATO EUROPEO PER LA PUBBLICAZIONI SCIENTIFICHE

Via Val d’Aposa 7 – 40123 Bologna – Italy

[email protected] – www.seps.it

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

INTRODUCTION

On Friday 18 February 1564, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine patrician and ‘divine’ sculptor, painter and architect, lay dying in Rome in a part of the city called Macello dei Corvi. It was a small house with a few of the ground-floor rooms converted into workshops, a forge for making tools and a kitchen. The bedrooms were on the first floor.

Five days earlier on Carnival Monday, someone had seen the little old man, hatless and dressed in black, walking in the rain that chilled the city. They had recognized him, but did not have the courage to approach him. They notified Tiberio Calcagni, a pupil who looked after him like a son, but he too did not find it easy to persuade the famous artist to return home. He would not hear of taking a rest: his aches and pains, he said, gave him no respite. He attempted to ride his black pony, as he always did when the weather permitted, and he started to panic when he realized that he couldn’t manage it and would never be able to ride again. Although he had been expecting death for decades, now that it had arrived with that cold rain, he was frightened just as we all are – even those of us who, like him, have lived far into old age. He slowly yielded to death in the care of another pupil, Daniele da Volterra. For two days he waited in an armchair by the fire, and then in his bed for three more. As the angelus rang out on Friday morning, a still alert Michelangelo died in the care of Tommaso de’Cavalieri, Diomede Leoni and Daniele da Volterra.

Macello dei Corvi was a part of Rome close to the Foro Romano, the Foro Imperiale and the slopes of the Quirinale. Drawings of antiquities by travellers and scholars provide us with a very clear idea of the area the artist’s house overlooked at the time: it was an uncultivated countryside from which the skeletons of antiquity’s greatest monuments emerged. The greatest of all these was the Coliseum, that mountain made of travertine stone and riddled with holes, whose base was still buried and whose arches and vaults had turned into caves that were home to a great variety of precarious lives. Then there were the great triumphal arches, which were also half submerged in the ground, and on cold days like the ones that brought Michelangelo’s life to an end, the sheep and cows huddled around them to shelter from the rain, and pressed against the marble reliefs sculpted to commemorate the eternal glory of the emperors. The huge columns of the Temple of Saturn rose above the ruins and the ancient trees that grew there, and were crowned by the white marble of the entablatures miraculously suspended in the sky.

The neighbourhood in which Michelangelo lived bordered the level area of the Fori to the north and marked the beginning of the medieval and Renaissance city. It was hardly one of the elegant sites of the new Rome. It was almost countryside, with vegetable gardens and vineyards that found their way in amongst the ruins of the ancient city – the same ruins that Michelangelo had studied and drawn on his arrival from Florence sixty years earlier, under the careful tutelage of the venerable Sangallo. For at least a century, the papal strategy had been to concentrate the ‘rebirth’ of the city of Rome on its other side, where the Tiber forms a tight bend between Castel Sant’Angelo and Tiberine Island. Since the final years of the fifteenth century, Italy’s best architects had been attempting to revive ancient architecture. Of course, they had to make do with resources that were infinitely more restricted than those of the ancient Romans, but their ingenuity had overcome this obstacle, which in many ways had encouraged creativity. Raphael, Bramante, Peruzzi and the Sangallo family were all excellent artists whom Michelangelo had known and who had since died, and they had built palazzi in that area which looked as if they had been there since antiquity. These white buildings decorated with columns and rustication were impressive additions to the wide and straight avenues that open a breach in the maze of insalubrious alleys which Romans crowded into throughout the Middle Ages, like a shipwrecked people who had adapted themselves to life in the wreckage of a vast ship.

None of these new buildings could be found on the streets around Michelangelo’s house. The only town-planning measures that had been taken were those of Paul III, who demolished the shacks that clustered around Trajan’s Column, the giant trunk of marble on which bas-reliefs depicted the deeds of the Roman emperor. He did this to impress another emperor, Charles V, who came in 1536 to stage a triumphal ride into Rome following a victory over the Turkish admiral at Tunis. With a very modern sense of theatricality, Paul III decided to free the city’s ancient monuments of the clutter that surrounded them, in the certain knowledge that this would have made a strong impression on the visitor who was susceptible to the power of ceremony.

Otherwise Macello dei Corvi was an unassuming part of Rome, to say the least. The houses were mainly on two floors, and pressed together so that there was no room for courtyards. They were built from the debris lying in the corpse of the ancient city: badly cut tufa rock from the Viterbo area was mounted on lines of Roman bricks taken from the old walls, and sculpted blocks of peperino or travertine were cemented and used as cornerstones, thresholds and lintels for doors and windows, without a care for the sophisticated bas-reliefs on their surfaces. Occasionally this dubious hotchpotch of building materials had the protection of a plaster made from volcanic ash, which was livid red or purple depending on the quarry it came from – almost always a vineyard just inside the Aurelian Walls.

Michelangelo came to live in this poor area of Rome around 1510, when Julius II or his heirs had provided him with that house and workshop so that he could work on the sculptures for the planned tomb of the great Della Rovere pope. He left Rome in 1517, only to return there in 1533 as a now world-famous artist. During the years that followed, his financial and social advancement never ceased, and yet he never left that squalid house so distant from the centre of the papal court. His continued presence in that district on the then outskirts of Rome demonstrates how he never wanted to integrate into a city where, for thirty years, he essentially felt himself to be a Florentine exile.

Even the circumstances of his death were typical of an exile, in spite of his undoubted fame. The short illness that broke him came without warning. One morning at the beginning of the previous October, he turned up at the church square of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in excellent health and in the company of his faithful servants, Antonio del Francese and Pier Luigi da Gaeta. He may have gone to attend mass, but was certainly interested in taking another look at his beloved Pantheon, the best preserved building from antiquity, which alone, in his opinion, demonstrated the unattainable beauty of which Roman builders had been capable. In the square in front of the church he was recognized and greeted reverentially by another Florentine, Miniato Pitti, who later described the old artist as a man who ‘goes around with a stoop and can hardly lift his head, and yet he stays at home and continuously works away on his sculpting’.1 Almost ninety years old, Michelangelo was still working. And he was not working with his pencil, but with his chisel.

The vigorous old man who came to that meeting in the church square of Santa Maria sopra Minerva on horseback would die four months later in his miserable home in Macello dei Corvi. He died alone, without the presence of a single one of his relations for whom he had worked and saved all his life – not his nephew Leonardo, whom he had loved but kept at a distance, in Florence, because he hated the idea of his nephew awaiting his death to take possession of his wealth. And yet Leonardo could count upon that wealth, as one of the principal aims of Michelangelo’s had been to make the Buonarroti line rich and respected.

Although historians would attempt to transform Michelangelo Buonarroti into a mythical figure much accustomed to the luxury of the princes he served, the circumstances of his death, so carefully chronicled by the witnesses to it, tell of a fierce and irredeemable conflict between the artist and the rest of the world. The only exceptions were a few simple people who he allowed to look after him and Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, a Roman nobleman that Michelangelo had loved too much to refuse his presence during the last days of his life. The account provided by these people detailed his agony hour by hour, and this made it difficult to create romantic interpretations that could shroud him in the mystery and greatness of which legends are made.

For Michelangelo, as is often the case, the circumstances of his death were extremely revealing. Like everyone facing death, he was not prepared for it and begged like a child never to be left on his own, even for a second. But as soon as it arrived in his extremely modest home, death discovered another weakness in this man: the avarice that afflicted him all his life. A chest full of gold, sufficient to buy the whole of Palazzo Pitti, was hidden under his bed. He trusted no one, not even the banks. He always feared deceit, persecution and fraud. He lived like a wretch, while accumulating money in a wooden chest under his bed. The man who was the object of veneration during his life should have provided his public with another death – one that did not involve a frightened and suffering old man slowly fading while he desperately struggled to cling onto life right up to the last second.

That death was soon to be remodelled by the commemorative works of two of the most brilliant Florentine intellectuals and members of the Academy, Giorgio Vasari and Vincenzio Borghini, who were committed to enhancing the public image of Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici of Florence. As soon as they heard of the great artist’s death, they immediately set about transforming and cleansing it of every defect and affliction to use the old master as an initial step in the creation of a new narrative for Florence – all part of a far-reaching and wide-ranging political project. The weakness of the state Cosimo I inherited after the assassination of his savage cousin Alessandro convinced him that one of the ways to make the duchy more secure and, above all, to reach a peace agreement with the republican exiles whose wealth and intelligence he badly needed, was to exalt the social and cultural identity of the Florentine nation. Michelangelo was destined to play a key role within this strategy, because he was the very symbol of Florence’s talent and its most loved and famous son, in spite of attempts by bankers and aspiring princes to link their names to the city.

During his life Michelangelo, always a resolute republican, would never have wanted to support such a project. He never wanted to return to Florence, in spite of the duke’s requests, nor was he generous to Florence with his works. Until the death of the French king, Francis I, in 1547, he harboured vain hopes of seeing the city freed of Medici rule. After that he resigned himself to a more respectful attitude as befitted his own dignity, and which was just sufficient to avoid problems for his heirs and for the wealth he had accumulated in the city and its surrounding countryside. Vasari expended a great deal of energy on this project, possibly because he felt sincere admiration for the quintessentially Tuscan artist, but undoubtedly to please his duke. He had constantly enticed Michelangelo with all kinds of proposals, always pointing out the advantages for his descendants, as he knew the ageing artist was sensitive to this argument. But it had all been in vain. Michelangelo’s excuse was always the need to finish the work on St Peter’s, an undertaking that genuinely was for him a votive offering made directly to God. He didn’t want to move from Rome even when the election of Pope Paul IV (Gian Pietro Carafa) meant that his life was no longer safe. His unswerving hatred of the duke and the pope was demonstrated by the destruction of his own drawings and cartoons, which he ordered as death approached. He had them burnt, even though Cosimo I would have paid him any price for them. Indeed, the duke put aside his usual princely reticence and expressed his exasperation with the stubborn artist: ‘We regret this vexation of his not having left any of his drawings: it was not an act worthy of him to have thrown them on the fire.’2

But now that the stubborn old artist was dead, no one could hold back the demands and plans of the powerful to whom he had not submitted throughout his life. Power now had a free hand to manipulate his mortal remains and his myth. It was the moment everyone had been waiting for. On hearing that he was dying, cynical Don Vincenzio Borghini immediately understood that Michelangelo’s death would provide an excellent opportunity to improve what we now call the ‘image’ of the Florentine Academy and its patron, Cosimo I. ‘Consider what I have to tell you; on occasions the malevolence of those envious of other people’s virtues provides the opportunity to do things that enhance the reputation of the person who does them rather than that of the person for whom they are done. Now, as I have said, you will think about this; all I have to do is to get things moving, and you will bring them to completion.’3 Borghini was all too aware of the advantages of a state funeral: Cosimo, the enlightened monarch, would reward virtue, make it more fruitful with his generosity and acknowledge the great worth of one of his sons. How could anyone accuse such a man of tyranny? How could you challenge the virtuous foundation of the Tuscan state that was now identified with the Medici? The exiles were completely outflanked by a propaganda campaign that used one of the most revered symbols of the entire century. To make this operation even more effective, the funeral oration was entrusted to Benedetto Varchi, a highly respected republican exile who had returned to Florence twenty years earlier at Cosimo’s insistence – the initial stage of the prince’s policy of winning over and seeking reconciliation with his republican opponents (at least those he did not have murdered by his hired assassins).

However, they had to move quickly and adeptly. Other powers were claiming the right to bury the famous corpse so as to bathe in the artist’s reflected glory. The strongest of these contenders was the papacy, which had incessantly provided Michelangelo with work for the previous thirty years. A commission set up by the governor of Rome rushed to the house in Macello dei Corvi as soon as they heard of the artist’s death on Saturday, and Alessandro Pallantieri, the governor himself, followed shortly afterwards. As in the case of a pope or a king, they had to draw up an inventory of all the assets contained within the house. But their real intentions soon became very clear, when the artist’s nephew and legitimate heir arrived in Rome. Leonardo, whom Michelangelo had so dearly loved, was threatened and they told him sharply that he was lucky to have the money they were leaving behind or, in other words, the chest with the ten thousand ducats the old man foolishly kept in his home. There was no trace of the works, some drawings and three unfinished statues. That was the real treasure – one of inestimable worth – but the guards had been ordered to take everything away.

Leonardo understood that the best service he could do for his prince, Cosimo I, was to bring back his uncle’s dead body to Florence. Fortunately it was a very cold winter, and the corpse was well preserved. The body was stolen at dawn from the Church of the Santi Apostoli, where it had been temporarily placed, and loaded on a cart for transporting goods. When it arrived in Florence three days later, Cosimo, Vasari and Borghini sought to keep this a secret in order to stage-manage the event better. Besides, Michelangelo was still the most important symbol of republican beliefs, and in Florence you could never be absolutely sure that the republican opposition had been entirely defeated. Yet rumours of what had actually occurred were soon circulating the city. First the artists and then the people, or certainly the republicans amongst them, held a procession through the night to revere the artist’s remains like those of a saint. Thousands of men in tears marched in silence, and they were dressed in the same worn black smocks and ‘shabby’ jackets that the meticulous author of the inventory had discovered in Michelangelo’s wardrobe. By embracing him in this spontaneous manner – an honour no one else had ever been accorded – the Florentines repaid the artist’s immense love for his native city that had never dimmed, and which he had paid for with his exile.

Then it was time for the state funeral in San Lorenzo, the family church of the Medici, on which they could finally bestow the glory of Michelangelo, just as they had taken possession of the statues he had never wanted to give them while he was alive: his unfinished Prisoners and Victory for the tomb of Julius II had been left in his house in Florence. The most obvious thing would have been to put those sculptures on the artist’s tomb, but Vasari immediately found a way to replace them with the Pietà which Michelangelo had defaced and given to Francesco Bandini. In this way, the sculptures could become Duke Cosimo’s personal possessions. The plan was suggested to the compliant nephew Leonardo a few days after the artist’s death, and not even the refusal by Bandini’s son to hand over the Pietà was enough to deter the single-minded Vasari from his plan. It was easier to betray Michelangelo than to disappoint Cosimo I. It was decided that the tomb should go without, and the young sculptors of the Academy were given the task of making alternative statues, which to this day offend the artist’s memory with their ugliness. In the end, the Duchy of Florence had its champion of virtue, and the duke had his sculptures.

In Rome they also breathed a sigh of relief. Carlo Borromeo immediately gave orders to cover the nudes of The Last Judgement with those ghastly underpants and the work was completed by 1565. Michelangelo’s death meant the loss of one of the last remaining exponents of the Spirituali, a group that had engaged in the risky business of promoting reconciliation with the Protestant Reformation over the previous thirty years. At the heart of the Catholic world, Michelangelo had ‘illustrated’ this shared and effusive heretical faith using marble and paint, but now he was dead, the official Church could cleverly reintegrate him and his works. Daniele da Volterra was given the task of covering up the more ‘obscene’ nudes of The Last Judgement. Other works, such as the frescoes in the Pauline Chapel, could be assimilated with more sophisticated methods: they placed alongside his paintings, which were pervaded by a faith entirely different to the now dominant one that had triumphed at the Council of Trent, other didactic paintings that directed the onlooker towards more orthodox interpretations.

The myth of Michelangelo was destined to grow and to be manipulated in the years and centuries to come. His nephew Leonardo’s son, Michelangelo the younger (1568–1647), took the trouble to change the relevant endings from masculine to feminine when he came to publishing his great-uncle’s sonnets, in order to remove the unsettling shadow of their author’s homosexual passion. Nor could Hollywood, that great, modern factory of myths, refrain from exploiting Charlton Heston’s irresistible attraction to provide the mass market with a Michelangelo in love with a woman he actually never met.

The historical figure that has come down to us is difficult to make out precisely because of the excessive light that has been shone on him. That light has obscured the man and even his work. It was felt that his Moses, which is his most viewed statue, needed to be analysed and restored in order to discover what should have been obvious to an eye less blinded by prejudice and indeed what an important document also made clear: namely that Michelangelo had changed it completely when the work was already at an advanced stage and late in the artist’s life. However, the opening of the Vatican archives and the historical research of Adriano Prosperi and Massimo Firpo have finally clarified the ambiguous circumstances in which Michelangelo worked towards the end of his life. Restorations, particularly the masterly ones carried out under the direction of Gianluigi Colalucci in the Sistine Chapel, have made it possible to rediscover a craftsman who mixed plaster and colour, sculpted marble and scribbled ceaselessly on sheets of paper, and thus in part to separate him from the myth in which he has become entangled. The enormous quantity of documents that have been amassed since the mid-nineteenth century have been ordered philologically by Giovanni Poggi and subsequently by Paola Barocchi. This has recently been enlarged upon by Rab Hatfield’s indispensable work on the artist’s current accounts, which produced an often extremely harsh assessment of Michelangelo’s many vicissitudes, which he made every effort to varnish over in the versions he dictated to his biographers. Just as Charles de Tolnay edited a catalogue of Michelangelo’s works in the mid-twentieth century, Michael Hirst has more recently edited one of his drawings, and every year a myriad of specialist studies produce new and adventurous dissections of single works and single moments in the artist’s life.

The unequalled scale of this intense study of documentary sources is proof in itself of the fascination with Michelangelo and of the enormous volume of contemporary accounts about him. The most recent works produced in the last century are essential to any study of the artist, as they provide new interpretations founded on the endless quantity of documents, but they also make it increasingly difficult and daunting for the non-specialist to approach his works. By combining this careful academic study of the written sources with that of the material sources and his methods of painting and sculpting, this book attempts to relate the two different spheres to each other, and to interpret the artwork not simply as images but also as specific financial and technological undertakings in which the artist used up all his physical resources and to which he contributed all his human passion.

Following the important restorations of the Sistine Chapel and Julius II’s tomb, we now have new information that can be used for the first time in understanding Michelangelo in his totality: this knowledge can help us to neutralize the myth and get closer to the divine artist and the suffering man Michelangelo comprised. The results are stunning. On the one hand, the artist himself belies the myth, and on the other, his art becomes even more sublime, because it proves to be rooted in the miseries, conflicts and sufferings of a life that was ordinary in its grimness. Past centuries could not accept this apparent paradox, but modernity knows it only too well. This is undoubtedly the reason why Michelangelo continues to fascinate us as the most modern of all the artists who have ever lived.

Notes

1.

Letter from Don Miniato Pitti in Rome to Giorgio Vasari in Florence, 10 October 1563, in G. Vasari,

Der literarische Nachlaß Giorgio Vasaris

, ed. by K. Frey, 2 vols. (Munich: Georg Müller Verlag, 1923–1930), vol. II (1930), p. 9. Michelangelo’s last hours are recorded in great detail in the chronicle which Daniele da Volterra sends to Vasari a few days after Michelangelo’s death: ‘When he got ill, which was on Carnival Monday, he sent for me, as he always did when he felt unwell, and I sent word to Master Federigo de Carpi, who immediately came, but pretended that it was by chance [so as not to frighten him,

author’s note

], and then I did the same. As soon as he saw me, he said, “Oh Daniele, I am finished, I commend myself to you, and do not leave me”; and he made me write a letter to Master Leonardo, his nephew, that he should come, and he told me that I should await them in the house and should not leave for any reason. This is what I did, even though I was not feeling so well. His sickness lasted five days: two when he was up at the fireplace, and three when he was in bed. Thus he expired on Friday evening, may he rest in peace, as I believe we can be certain. On Saturday morning, while the house and the other things were being tidied up, the judge came with the governor’s notary on behalf of the pope, who wanted an inventory of what was there. We could not prevent this, and so everything that was there was written down: four cartoons. One was that one … another was the one that Ascanio was painting, if you recall; and one apostle, which he was drawing so that he could sculpt it in marble in Saint Peter’s; and one

Pietà

, which he had started on, and of which you can only make out the pose of the figures, as there is little finish. That’s it, the one of Christ is the best, but all have been taken away, so it will be difficult to see them, let alone have them back. Nevertheless I have reminded Cardinal Morone that it was an undertaking for him, and offered to make him a copy, if I can ever get it back. Some small drawings – those Annunciations and the Christ in the garden – which he gave to his Jacopo [Jacopo del Duca,

author’s note

], friend of Michele [Michele degli Alberti,

author’s note

], if you remember. But the nephew will take them away in order to give something to the duke. No other drawings were found. Three unfinished marble statues were found: a Saint Peter dressed as a pope, … a

Pietà

in the arms of Our Lady and a Christ holding a cross in his arms, like the statue of Minerva, but smaller and different. No other drawings were found. The nephew arrived three days after his death and he immediately order that his corpse be taken to Florence, just as he had ordered many times when he was well and even two days before he died. Then he went to the governor to have the return of the said cartoons and a chest in which there were ten thousand in ducats of the Chamber and in the old ones of the sun and about one hundred in coin, which equalled the count made on a Saturday for the inventory, before the body was taken to the Church of the Holy Saints. The said chest was immediately handed over with the money inside, which was sealed. But the cartoons have still not been returned, and when he asks for them, they tell him that he should be happy with having had the money. So I don’t know what will come of it’ (Daniele da Volterra to Giorgio Vasari on 17 March 1564, p. 53).

2.

Cosimo I de’ Medici in Florence to Averardo Serristori in Rome, 5 March 1564, in F. Tuena,

La passione dell’error mio

(Rome: Fazi, 2002), p. 205.

3.

Vincenzio Borghini to Giorgio Vasari, 21 February 1564, in Vasari,

Der literarische Nachlaß

, ed. by K. Frey, ibid., vol. II, p. 23.

1CHILDHOOD

1 THE BACK OF BEYOND

Four long hours remained until daybreak. The small house was at the top of a cliff overlooking a forest in the grip of a winter freeze. On the northern side, where the walls followed the edge of the cliff, the windows did not open because the wind from that direction was unremitting. However, the side that looked onto the village’s little square, had three windows on the first floor, which corresponded to three minuscule rooms where the maids bustled around and where the householder Ludovico was trying to find escape from his increasing anxiety.

The thick walls of the house, made of grey, clayey rock quarried from the mountainside, were not thick enough to muffle the screams of the woman about to give birth to her second child. It was not only the isolation of their home that worried Ludovico, who had already been through this torment, nor was it the fear that assistance would never reach a mountain top in Casentino. At that particular moment he could only think of his wife’s fall from a horse six months earlier, while they were moving to this godforsaken spot. Even though she was three months pregnant, the journey was hard and giving birth promised to be risky in a place perhaps never before visited by a doctor, he had had to accept the post of the governor [podestà] of Florence’s most insignificant possession to save himself from financial ruin. The salary was derisory, a mere 500 liras for six months, out of which he had to pay for two notaries, three servants and a stable boy. But he had no choice; they were certainly not going to offer him the governorship [podesteria] of one of the wealthier Florentine possessions, which came with salaries of 2,600 or 3,000 liras. He had now slipped far down the social scale, to the point of compromising the financial security and dignity of his own family. He was even close to losing his privileges as a citizen, and such a loss would have made him indistinguishable from the socially insignificant mass of craftsmen, salaried workers and artists.

Gone were the days when the family could boast a leading position amongst Florentine patricians. Two centuries earlier, Ludovico’s ancestor Simone di Buonarrota had been in the Council of the Hundred Wise Men. His grandfather, Buonarrota di Simone, wool merchant and moneychanger, had lent a large sum of money to the Florentine government [Comune] and had been elected to the most prominent public offices. Unfortunately he died too young, at just fifty, in 1405, and when he went to his grave, he also took the family’s rising star. The decline started with Ludovico’s father, Leonardo, and resulted from expensive dowries for his daughters, unpaid taxes and increasingly miserable postings. He too accepted that insignificant governorship twenty years earlier, and took his children with him. Perhaps this explains why Ludovico accepted. That dismal village must have appeared familiar and preferable to an equally desolate castle in a place he did not know. Nonetheless his wife was pregnant, the journey had been long, and she had fallen from her horse with unknown consequences for the unborn baby. And now there were still four hours to go before daybreak.

The screams suddenly became more desperate and equally suddenly they ceased, to give way to the triumphant crying of a baby who had made it into the world. He had managed to be born above that inhospitable ravine and seemed to be a healthy baby. The village in which he had chosen to make his appearance in the world was called Caprese, and from that morning it would start to occupy an increasingly respectable place in the world’s historical memory. The child would be called Michelangelo, and would become a painter, sculptor, architect and eventually the most famous artist of his time. Of the places that would form the backdrop to his long life – the greatest and most magnificent of these being Florence and Rome – that desolate land overhanging a deep Apennine valley and only fit for goats has the most to say about his savage and unsociable character, even though he left only a few months after his birth.

The day that finally put an end to Ludovico’s anxieties was 6 March 1475, but for the Florentines who followed a calendar in which the year began with the Incarnation, which according to tradition was 25 March, that date corresponded to 6 March 1474. Ludovico diligently recorded the difference between these dates in his memoirs:

Today I put on record that on this date of 6 March 1474, a male child was born to me. I gave him the name Michelagnolo, and he was born on Monday, four or five hours before morning… . Note that the date 6 March 1474 is from the Incarnation in the Florentine mode, and from Christmas in the Roman mode, it is 1475.1

The night that greeted Michelangelo into the world had stars that fortunately were unconcerned about the different dating system which, like so many other things, divided the statelets of Italy. In Rome it was 6 March 1475, in Florence it was 6 March 1474, but in the heavens Mercury and Venus were entering the second house of Jupiter and determining a destiny strongly influenced by sensuality, albeit a sensuality depicted in every way and hardly ever experienced.

Two days later on 8 March, Michelangelo was baptized in the small church of San Giovanni, a saint who was dear to the Florentines, in the presence of the church’s rector, a notary and a few of the townspeople from Caprese. Ludovico’s term of office ended on the 29th of that month and, as soon as they were ready to travel, the family left for Florence. Michelangelo, however, did not, as he was handed over to a wet-nurse in the small town of Settignano, some three miles from the city, where the Buonarroti owned a small property: ‘A farm … with a house for a gentleman and a labourer, and cultivated fields and vines and olive trees,’2 which produced an income of only 32 florins, but later Michelangelo would transform it through subsequent purchases into a substantial estate.

The use of a wet-nurse was customary in Florence, where scholars unsuccessfully attempted to argue the importance of the bond created between mother and son during breastfeeding. Anyone who wished to demonstrate their affluence was required to hand over their children to wet-nurses, leaving the natural mother with the only task of any importance to the husband, that of fertile producer of an unending succession of children. In Florence, the family was essentially a male preserve, just like business and the affairs of state. The custody of new-born babies was personally arranged by the father, who signed a contract with the wetnurse’s husband or father. Women were simply chattels, and never took part in this trade between families. The mother was very quickly excluded from the education of her children, who almost immediately after their return home were subjected to a family ethos that was exclusively male. Women were held to have such an inessential role in this transmission of the family’s ethos and bloodline that, in the event of widowhood, they were compelled to abandon their children and their dead husband’s home, taking their dowry in the hope of finding a new home in which to use their reproductive apparatus in the service of another man.

Children were entrusted to a wet-nurse for a period of about two years, until they were weaned. Generally the original family supervised the child’s development from a distance. Only a few families could afford to keep a wet-nurse under their own roof or even in Florence. More usually, they entrusted the babies to young women in the Florentine countryside, as these were less expensive than wet-nurses in the city.

Settignano looked over Florence and the Arno Valley. Then, as now, olive groves and vineyards flourished there. It was the area in which they quarried the pietra serena, a grey clayey rock that was easy to work and had been used for centuries for the most important buildings in the city. Brunelleschi had used it to make perfectly geometrical columns and arches. The quarries of pietra serena had developed into a highly profitable industry, and everyone in Settignano worked the stone in some way: they quarried it, they cut it and they shaped it. When they became particularly skilled, they moved down to Florence and opened a sculptor’s workshop. Occasionally they specialized, as did Desiderio with his melancholic madonnas. In other words, it was a town of stonemasons, and the wet-nurse who took in the little Buonarroti was a stonemason’s daughter and a stonemason’s wife. Michelangelo would later say that the decision to hand him over to that home determined his fate to be a sculptor, given that the first sounds he heard were undoubtedly those of the chisel on stone and the milk he drank was mixed with marble dust. But the coldness of the marble in whose company the baby grew could be seen as a symbol of another dramatic feature of his destiny: the coldness of family emotions that would cause him much suffering throughout his life.

2 MAGNIFICENT AND HEARTLESS FLORENCE

The Florence that greeted little Michelangelo is much easier to visualize than to understand. Its image is preserved with the clarity of a spring day in Francesco Rosselli’s Veduta della catena, which he drew in 1472 with the analytical technique that suddenly brought Florentine artists to the cutting edge of figurative representation. It is much more diffi cult to penetrate the complex mechanisms of government of a city-state which formally had all the appearance of a republic, but in reality was using highly sophisticated and modern methods of control to become a secular principality under the dominion of a family of bankers. Even in the twenty-first century, historians are excited by and divided over the forms of powers developed at that time.

The population of Florence, which had reached 80,000 in the period immediately preceding the Black Death in 1348, was struggling to get back to 40,000 at the end of the fifteenth century, and the city was fighting with all its prodigious energies to maintain a leading role amongst the Italian states, whose balance of power was always precarious: the Church, the Kingdom of Naples, Venice and the Duchy of Milan were being fought over by foreign powers. Florence’s particular strengths were the wealth of its trade and the rationalism of its political organization, which explained the intelligence of its alliances with other states, which in turn were essential to its domestic autonomy.

Francesco Rosselli’s view of the city shows how this organization was translated into town-planning (Fig. 1.1). The city was a discrete and fully formed entity. The districts, which brought together and organized the population, acted as intermediaries between the family clan – the true political unit of the city – and the municipal authority. Each one was gathered around one of the churches built in the previous century, Florence’s golden age: Santa Croce, Santa Maria Novella, Santa Trinità and Badia, which all still had gothic forms, and San Lorenzo and Santo Spirito, which had an apparently very new design but actually one that went many centuries back in Italian history. Only a class fixated on the singularity of its own destiny could have accepted such a stunning and creative rigour.

Figure 1.1Francesco Rosselli, Veduta della catena [View of the Mountain Chain]. Detail of Francesco Rosselli’s view of Florence. Vatican Apostolic Library,Vatican CitybpK/Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Photo: Jörg P. Anders

Clear straight roads linked the strategic points of the city, and passed the seats of the many powers that challenged each other. Above all, there was the cathedral, around which the entire view and the city itself appear to have been built. The Florentines had wanted it to be vast and covered by Brunelleschi’s miraculous dome to celebrate the faith of their citizens, which was quite distinct from the authority of Rome – something they had never held in awe. During that very period, they had hanged a bishop from a window of the palazzo comunale for having meddled a little too much in local politics. In order to make absolutely clear the extent to which Florentines were attached to their independence, the bishop was hanged in the company of other condemned men and left there for a few days. Even the children could understand the lesson.

Just as imposing as the cathedral and piercing the skyline with the most famous crenellated tower in Italy, Palazzo della Signoria was the government’s military garrison and located close to the Arno. It was supported by Palazzo del Bargello (then Palazzo del Podestà). In Rosselli’s drawing, it is possible to make out other places, no less representative of the city’s life, around these strongholds of power. These are the palazzi of the aristocracy, not knights or feudal nobles but patricians of wealth, mainly merchants and bankers, who had acquired the right to govern one of Europe’s richest cities by themselves. Because of its elevated position, Palazzo Pitti stands out and dominates the district of San Felice along Via Romana on the other side of the Arno. Others, however, can be confused with the surrounding buildings: so the Palazzo dei Rucellai, the Palazzo Spini Ferroni at the entrance to Holy Trinity Bridge, and the Palazzo dei Medici, which was built by Michelozzo in the north of Florence in a district which, even by the time of Rosselli’s drawing, had become a little family enclave, a city within the city with its own church (San Lorenzo), its own monastery (San Marco) and numerous other annexes, gardens and houses to suit the social and military needs of the rich family that held Florence’s destiny in its hands.

Rosselli’s drawing also shows extensive empty areas, and these were used for vegetable gardens on the precious land within the city walls. It had been the hope of the Florentine government that these areas would be filled with the houses of new citizens, but the demographic growth was not keeping up with that of the previous century. Another significant reality that is clearly shown in the drawing is the huddle of several buildings, connected in various ways to create a kind of insula within the district. Each of these groups of houses belong to a family clan, the nuclei that reflected the basic form of the city’s social structure. Governed by one or more men, the clan found that this spatial aggregate could interact with the city as a political unit with a strength that could not have been attained by any individual or householder. It was the simplest and crudest form of the Florentine consorteria, an association that bound together its members and would mark all the subsequent history of the city. Above the family consorteria there was the district consorteria and then the city consorteria: the three most significant administrative layers in republican Florence.

Finally, in the bottom-right corner of the drawing, in the vicinity of Porta Romana, we can see some condemned men who have been hanged from delicate little trees and left to rot in the air for all to see.

It was a clear warning that the city, whose order and prosperity was reflected in its many palazzi, could display in a manner that no other city could. Not even Rome, for all its princes and cardinals, was founded on such severe and brutal social relations and laws. Florence was not a merciful city, but rather a practical city – practical to the point of cynicism. While Rosselli was carefully capturing this architectural marvel in a drawing to be left to posterity, another Florentine, who was no less intelligent and no less passionate about his native city, started writing a simple but unfaltering diary, which guilelessly tells of the everyday life within those elegant walls and on those proud streets. This memoir helps us to imagine what little Michelangelo felt and saw on return from exile in Settignano:

And around 8 o’clock in the evening of 17 May 1478, young lads disinterred him again, and with a piece of noose that was still around his neck they dragged him around the whole of Florence. And when they were outside the door of his house, they put the noose through the ring-shaped knocker and pulled him up, saying ‘knock at the door’, and then around the city they did many other acts of derision. And when they were tired and didn’t know what to do with him, they went to the Rubaconte Bridge and threw him in the Arno. And they made up a song that contained worthless little ditties, one of which went as follows: Messer Jacopo went on his way down the Arno … And seeing him floating down under Florence and seeing him always on the surface of the water, were the banks and the bridges watching him go by.3

This is Luca Landucci’s description of how they tormented the corpse of Jacopo de’ Pazzi, one of the authors of the plot against the Medici family on 26 April 1478. Lorenzo de’ Medici had more than seventy men slaughtered in a few days, in part to punish the conspirators but principally to free himself once and for all of his political opposition in the city. He had them hanged at the windows of the palazzo comunale, and every now and then one of them was dropped to the ground so that the poor could steal their stockings and clothes. One of the plotters, a priest, met with an even more horrific fate: he was quartered in the square, and then his head was removed, placed on a pike and carried around for a whole day. Little Michelangelo had just arrived in Florence, and they were still carrying him on their shoulders. These scenes made such an impression on him that he retained a vivid memory of them until the day he died.

3 A RESTIVE APPRENTICE

In Francesco Rosselli’s drawing, you can see the great bare facade of the church of Santa Croce just behind the palazzo comunale. The church is wedged between houses of the district which bears the same name. The houses of the Buonarroti are amongst them. On several occasions during the fifteenth century, before the family went into decline, some of its leading members were put forward to represent the district in the election of the Dodici Buonomini, one of the most important bodies in the city’s government.

As a small child, Michelangelo would certainly have found his family’s city home unfamiliar. He must have had similar feelings about Francesca, his mother, who by 1477 had already given birth to another of Michelangelo’s brothers, Buonarroto, and then gave birth to Giovan Simone in 1479. She still had enough time in this world to bring Sigismondo into it in 1481, before dying that same year, probably from childbirth. During the six years in which Michelangelo had a mother, everything conspired to prevent her from looking after him: the lack of maternal warmth left the child with the emptiness that was responsible for all the pain of his future life. Typically for a Florentine of the period, Ludovico lost no time in finding another wife and in 1485 he married Lucrezia degli Ubaldini. But he was no more fortunate on this occasion, because he was a widower once more in 1497 and had five children to look after. Before getting a position of some importance within the administrative system, he would have to wait until 1510, when he obtained the governorship of San Casciano.

In accordance with the family tradition, Michelangelo should have received a classical education, a respectable beginning for a career as a merchant, banker or money-changer. Unfortunately financial difficulties drove Ludovico to put the young Michelangelo into an artisans’ workshop. According to Vasari, this occurred in 1488, but documents show that it must have been much earlier, given that the child was already collecting a payment from the Ghirlandaio brothers on 28 June 1487, when he was twelve years old. The trust the employers were putting in the small boy suggests that he had been working for them for some time: ‘Domenico di Tomaso del Ghirlandaio must pay on 28 June 1487, three florins [fiorini larghi], which Michelagnolo di Lodovico changed to 17 liras [pounds], 8 soldi [shillings] …’.4 Whilst still a child, Michelangelo started off on a life of hard work, as was the custom for those who were to take up the trade of artist in Florence at the time. This was perhaps the only moment when his life was similar to that of other artists about whom we have information.