17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

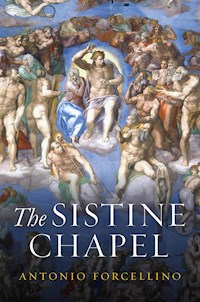

The Sistine Chapel is one of the world's most magnificent buildings, and the frescos that decorate its ceiling and walls are a testimony to the creative genius of the Renaissance. Two generations of artists worked at the heart of Christianity, over the course of several decades in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, to produce this extraordinary achievement of Western civilization. In this book, the art historian and restorer Antonio Forcellino tells the remarkable story of the Sistine Chapel, bringing his unique combination of knowledge and skills to bear on the conditions that led to its creation. Forcellino shows that Pope Sixtus IV embarked on the project as an attempt to assert papal legitimacy in response to Mehmed II's challenge to the Pope's spiritual leadership. The lower part of the chapel was decorated by a consortium of master painters whose frescoes, so coherent that they seem almost to have been painted by a single hand, represent the highest expression of the Quattrocento Tuscan workshops. Then, in 1505, Sixtus IV's nephew, Julius II, imposed a change in direction. Having been captivated by the prodigious talent of a young Florentine sculptor, Julius II summoned Michelangelo Buonarroti to Rome and commissioned him to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Two decades later, Michelangelo returned to paint The Last Judgement, which covers the wall behind the alter. Michelangelo's revolutionary work departed radically from tradition and marked a turning point in the history of Western art. Antonio Forcellino brings to life the wonders of the Sistine Chapel by describing the aims and everyday practices of the protagonists who envisioned it and the artists who created it, reconstructing the material history that underlies this masterpiece.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 408

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue: Turks in the Port

A War by Other Means

The War of the Painters

Note

Part I Affirming Papal Primacy

1. Rebuilding the Sistine Chapel

Notes

2. A Consortium

Note

3. The Starry Ceiling

Note

4. Evaluating the Four Panels

5. The Florentine Workshop in the Mid-Quattrocento and the Fresco Technique

Note

6. A Single Vision

Note

7. The Differences

8. The Apostles’ Wardrobe

Notes

9. The Ideal City

10. The Dance

11. The Iconography of the Cycle

Notes

12. Propaganda

13. No Rules at All

Notes

Intermezzo: Leonardo’s Impossible Project

Notes

Part II The Giant Climbs Skywards

14. Adieu to the Starry Ceiling

Note

15. Art Celebrates the Triumph

16. The Crack

17. An Enterprise without a Plan

Note

18. The Choice

19. Benvenuto Cellini and Optical Projections

20. A Platform Suspended in Mid-Air

Notes

21. The Fight for the Job

Notes

22. The Power of Obstinacy

Notes

23. The Crisis

Notes

24. ‘I Am Still Alive’

Note

25. The New World

Note

26. From Story to Spiritual Ritual

27. The Break of 1510

Notes

28. A New Battle

29. Revolution in Paradise

30. The Miracle of Creation

Notes

31. The Triumph

Note

Intermezzo: The Crucifix of Santo Spirito

Notes

Part III The Golden Age

32. Raphael’s Hour

Note

33. Another Genius in the Chapel

34. Raphael’s Tapestries

Notes

35. The Image Reversed

36. The Monumental Style

Notes

37. The Acts of the Apostles: The End of a Long Story

38. Production Methods in the Workshop: A New

Notes

Relationship between Artist and Collaborators Intermezzo: Two Marriages

Note

Part IV The Last Judgement

39. Commissioning The Last Judgement

Notes

40. A New Pope for an Old Project

Notes

41. The Iconographical Tradition of The Last Judgement

Notes

42. The Worksite

Notes

43. An Unprecedented Fee

Notes

44. The Whirlwind of History

Notes

45. The Drawings for Tommaso: A Model for The Last Judgement

Notes

46. The Power of Colour

Notes

Epilogue: A New World

Note

Index

Ebook plates

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue: Turks in the Port

Begin Reading

Epilogue: A New World

Index

Ebook plates

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

67

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

177

178

179

180

181

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

THE SISTINE CHAPEL

HISTORY OF A MASTERPIECE

ANTONIO FORCELLINO

TRANSLATED BY LUCINDA BYATT

polity

Originally published in Italian as La capella Sistina. Storia di un capolavoro.Copyright © 2020, Gius. Laterza & Figli, All rights reserved.

This English edition © Polity Press, 2022.

The right of Lucinda Byatt to be identified as translator of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book has been translated thanks to a translation grant awarded by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation / Questo libro è stato tradotto grazie a un contributo alla traduzione assegnato dal Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale italiano.

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press111 River StreetHoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4924-5

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022930583

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

PROLOGUETURKS IN THE PORT

A WAR BY OTHER MEANS

On 28 July 1480, some fishermen from Otranto who were preparing to go to sea at dawn spotted a shimmer of sails outlined on the horizon and heading towards the city. Anyone still lingering in bed was woken by the cries of people hurrying back from the port to bring news of the catastrophe many had been expecting for months.

The Ottoman galleys had left Valona, a city on the other side of the Adriatic that had been under Turkish control for decades. The Ottoman governor Gedik Pasha was in command of the fleet, which carried some fifteen thousand men, ready to land in Otranto and from there to invade Ferrante of Aragon’s kingdom before moving north, to the Papal States and to the heart of Christendom.

As the Ottoman horses and cannons were disembarked at Alimini, a nearby beach, a pitifully small number of troops rallied under the command of captain Francesco Zurlo, in a desperate and impossible defence of the city. The residents of the outermost neighbourhoods clustered around the city walls hastily carried what they could inside the fortified enclosure, and soon enough some five thousand people had gathered there. Others, with more foresight, escaped to the countryside, putting as great a distance as possible between themselves and the doomed city.

In the early afternoon, a small gig with Gedik Pasha himself standing at the bow slipped quietly over the flat, green water that lapped the city walls. Pasha was renowned for his intelligence and determination, although to many this looked more like cruelty. He was also one of the most trusted commanders of Mehmed II, the great conqueror of Constantinople, now confined to the capital as a result of an attack of gout that had left him with a swollen and misshapen leg. Gedik was coming to offer the residents of Otranto a chance to surrender to the sultan of the Sublime Porte and become his subjects, as the Christian citizens of Valona had done years earlier. Not only would their lives be spared but they would also be able to keep their religious freedom, providing that they paid the gizya, a tax levied from both Jews and Christians in lieu of the charitable tithe paid by Muslims, as their religion required. It was an entirely reasonable offer, which might even have improved the lives of many, since the king of Naples was neither magnanimous nor efficient.

But captain Zurlo had been deeply affected by the propaganda circulated by the popes and other Christian leaders, who saw the expansion of the Ottoman Empire as a threat to their own territorial power even more than to their religion. Although he had no chance of staving off such an attack, relying on promises of help from Christian princes that were never to materialize, Zurlo gave orders for a bombard to be loaded and fired at the approaching gig. It was an instantaneous declaration of war and violated the Ottoman diplomatic code, which regarded such negotiations as sacrosanct.

Gedik Pasha’s anger was made clear a few hours later, when the city walls came under heavy bombardment that continued for many days, alternating with the activities of the Ottoman sappers. Nonetheless, the first skirmishes gave Zurlo the false impression that he could win the battle, and this prompted him to order the violent deaths of the first Turkish prisoners. Appalling atrocities such as impalement and quartering would later be paid back to the population of Otranto with a vengeance.

The siege of Otranto lasted two weeks, enough time for any Christian army to be able to come to the city’s aid. But these commanders and their troops, including those of the heir of Saint Peter himself, Pope Sixtus IV Della Rovere, were too busy fighting each other, notwithstanding thatsome were not far from Puglia. Lorenzo the Magnificent, the ruler of Florence, had abandoned his allegiance to the pope, whom he had never forgiven for backing an attempt to overthrow the Medici in the Pazzi conspiracy two years earlier. Having escaped assassination and resumed control of the city, Lorenzo had then formed an alliance with the king of Naples and, together, they were now warring against the pope’s nephew, Girolamo Riario, lord of Imola. This had forced the pope to ally himself with Venice in order to face the combined attack of Florence and Naples. As a result, Venice was engaged in complex military campaigns not only throughout Italy but also across the Mediterranean, where its maritime trade was increasingly hampered by the Turkish expansion. With the political pragmatism that had allowed the Most Serene Republic to survive for five centuries, unlike many other states and republics, the Great Council had signed a general truce with the Sublime Porte in 1479, and in the days before the attack on Otranto it had ordered its ships out of this stretch of the Adriatic so as not to hinder Turkish naval manoeuvres. Having to choose between the friendship of Turks or Christians, Venice had prudently opted for the former. Nor was its pragmatism a secret. Friendship with the Christian rulers came at the price of rapidly changing alliances, and it was this that made the political geography of the Italian peninsula so unstable.

The Ottoman advance on the West had been underway for some thirty years or more, ever since Constantinople, the city known as ‘the second Rome’, had fallen to Mehmed II, who then proclaimed himself emperor and heir to the Romans. For thirty years, Christian rulers had put their own trifling dynastic affairs before the defence of Christendom and of the integrity of what, for a thousand years, had been the Holy Roman Empire. Crusades were announced and then immediately aborted through the conflicting interests of the various princes, who in the end had attempted to reach peace with the sultan in other ways. Venice itself, which was the Ottoman Empire’s main rival in the Mediterranean, had entered what seemed to be an alliance with Mehmed II. Now Mehmed had sent his highest vassal, Gedik Pasha, to present the bill.

The residents of Otranto, taken in by the religious propaganda of the Christian rulers and then effectively left to themselves, were almost all slaughtered after the final assault on 11 August, which marked a point of no return for the people of southern Italy. The Christians made their last stand in the sacristy, and then inside the cathedral itself. The bishop continued to recite the mass until his head was severed from the neck in one strike, with a sword, then displayed on a pike by the triumphant soldiers. The horrors that followed, once the inhabitants had refused conversion, were typical of any military defeat and any surrender, except that on this occasion it was the Turks who carried them out, in the very heart of Italy.

Understandably, when news arrived in Rome on 3 August, just five days after the siege had started, there was deep concern. Masses were celebrated, promises were made, and lastly a truce was announced between the Italian states, and especially between Sixtus IV and Lorenzo de’ Medici, who had been at each other’s throats. An alliance was needed to defend Italy’s borders from the Turks, but above all the pope needed to claim his spiritual legacy from Mehmed II, because the sultan, a great lover of ancient history and driven by a desire for conquest that made him identify with Caesar and Alexander the Great, claimed not only the temporal but also the spiritual rule of the universal empire whose leadership he had taken when he conquered Constantinople – the second Rome, which over the centuries had been much more powerful and influential than that hamlet of monks and sheep that the ancient city lying between the Tiber and the hills had become.

In the meantime, while waiting to conquer the first Rome, too, and to ride on horseback into Saint Peter’s, as his grandfather had dreamt of doing, Mehmed II made much of his claim to Rome’s spiritual and cultural legacy, which had to legitimate his dream of a universal empire. To many European intellectuals, his claims seemed well founded, because they were underpinned by facts that were hard to dispute. The legitimate base of his claim had already been acknowledged twenty years earlier, when Pius II wrote a letter to Mehmed in which he declared his readiness to recognize the latter’s imperial investiture, on condition that Mehmed converted to Christianity. Mehmed naturally refused. Albeit a tolerant sultan who guaranteed freedom of worship in his empire, he was convinced that his was the true religion and that it should become the leading religion in all the lands and nations that were steadily being added to his empire.

As if this were not enough, many in Italy regarded and continued to regard Mehmed II’s claims as being rightful. An authoritative cultural tradition championed his requests, on the grounds that anyone who conquered the second Rome was entitled to call himself Caesar’s heir. The pope of Rome, Sixtus IV himself, acknowledged that tradition and took the matter very seriously. If all European princes faced the problem of territorial threats, since they were required to defend their borders with armies, then he, the pope, was called to react to a much more insidious threat: one that threatened to render his spiritual leadership illegitimate.

Sixtus IV decided to respond to this threat with an artistic endeavour that became a sort of universal manifesto of Christian theology and papal legitimacy: the decoration of the Sistine Chapel, the most important chapel in Christendom, which he had just rebuilt and which, from 1481, he would entrust Italy’s best artists to embellish.1

THE WAR OF THE PAINTERS

While the defence of Italy’s and Europe’s territorial integrity relied on the armies and finances of the five main states on the Italian peninsula – Rome, Venice, Florence, Milan, and Naples – which had battled one another for almost a century but now, after the siege of Otranto, undertook to react to the Ottoman expansion, only Rome and the vicar of Christ could defend the legitimacy of Christendom as heir to the civilization and therefore legality of Rome. The reigning pope, Sixtus IV, was the right man for the job.

Born to a family of very modest standing, the pope had an exceptionally lively mind and was regarded as a distinguished theologian. His ascent through the curial ranks owed much to the brilliant solution of several doctrinal matters, which in previous decades had led to heated disputes between the leading religious orders of Dominicans and Franciscans. Sixtus also had a political energy that had already attracted much criticism during his papacy. He had launched a major rebuilding programme and significant works aimed at restoring Rome’s status and prestige after the years of neglect that followed the transfer of the papal seat to Avignon. A factor in the transfer to the French city had been the need to protect the papal court from the acts of arrogance of local baronial families, the Colonna, the Orsini, and the Savelli, whose armies were running riot in the city, endangering even the pontifical palaces.

One of the main projects launched by this energetic pope from 1477 on was the restructuring of the Cappella Magna (the Great Chapel) in the Vatican Palace. The masonry structure had now been completed, but the wall decorations were still lacking. Only, for this next phase, the pope needed the services of superb painters; and at the time almost all of them were in Florence. It was only after the truce with the Tuscan city that Lorenzo de’ Medici agreed to allow his best painters to leave for Rome. Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Cosimo Rosselli were joined by Pietro Perugino, who was Umbrian by birth and training but had a workshop in Florence, too, and had already been appreciated by the pope (he had painted the pope’s funerary chapel in 1479).

These painters would contribute with their art to the crusade that the pope intended to organize against the Turks, although another century would pass before that took place. A fresco cycle would be created inside the chapel of the Vatican Palace, the holiest place in Christendom, to prove to the world that the pope was the one and only heir of the Roman Empire. Mehmed and his universalist claims had to be refuted and rebuked with every possible weapon, both those in molten bronze that were cast by ballistic experts and those of propaganda that were laid out in gold and lapis lazuli on the walls of the world’s holiest chapel.

A visible affirmation of papal legitimacy was much needed, especially in Rome, where a current of thought sympathetic to Mehmed II’s claims had made headway in the most refined and academic circles. It was known, moreover, that in the conquered Christian territories beyond the Adriatic Mehmed’s government had shown itself to be more liberal and generous with the small people [il popolo minuto] than the Christian rulers had been. These intellectuals were deeply undermining the papacy’s cultural and moral legitimacy; hence they, too, needed an answer that could not be military but had to be cultural.

On the back of such ambitious aims, the Sistine Chapel became the centre not only of Christian spirituality and papal legitimacy but also of modern art. Yet the succession of artists who made the chapel memorable also tells another story, apart from that of the papacy’s legitimate descent from the Roman Empire. It tells the story of how art broke away from fifteenth-century rules and entered its modern dimension as a product of genius. Art began to be recognized as a product of pure talent and freed itself from the medieval heritage, which was still founded on the precious nature of the materials and the repetition of formal codes. The infinite horizon of the creative genius would be first glimpsed right here, in this chapel, where it would affirm its greatness through the work of Michelangelo Buonarroti and Raffaello Sanzio.

To follow the development of the chapel’s decoration over the course of two generations of artists is to follow a transition from the rules that governed the Renaissance workshop to the expression of a modern creative genius, which asserts its universality and greatness precisely in the breaking of that rule.

Note

The English translations of Italian primary sources not cited from published English editions are by Lucinda Byatt.

1.

On the siege of Otranto, see V. Bianchi,

Otranto 1480: Il sultano, la strage, la conquista

, Bari: Laterza, 2016. The book offers a balanced and unbiased retelling of the events of those years. On the universal claims of Mehmed II advanced after the conquest of Constantinople, see G. Ricci,

Appello al Turco: I confini infranti del Rinascimento

, Rome: Viella, 2011.

PART IAFFIRMING PAPAL PRIMACY

1REBUILDING THE SISTINE CHAPEL

A great chapel, cappella magna, had been built beside the Vatican Basilica when the first large palace was erected at the instigation of Pope Leo III (795–816). The site of this chapel, if not identical, must have been very close to the present-day one. The chapel was probably enlarged, and perhaps rebuilt under Innocent III (1198–1216).1

Under Nicholas III (1277–80), the Vatican Palaces were expanded and the Cappella Magna was also rebuilt or enlarged, as reported in a Latin inscription that is still visible in the Palazzo dei Conservatori: ‘Pope Nicholas III ordered that the palace, the great hall and the chapel be built, and he enlarged the other old buildings in the first year of his pontificate.’2 These buildings fell into decay during the Avignon papacy and were in part restored by Martin V (1417–31), but according to fifteenth-century sources and Vasari, it was Sixtus IV who rebuilt ex novo, from scratch, the chapel that we now see. Recent studies on the building show that, contrary to what Vasari wrote in his Lives of the Artists, the chapel was rebuilt on the foundations and in the area previously occupied by the Great Chapel. Therefore it was not so much a rebuilding as a renovation, which broadly speaking preserved the plan and the dimensions of the previous chapel.

Thanks to a curious event narrated by a chronicler of the time, Andrea of Trebizond, we know how ruinous this chapel had become. During the 1378 conclave, the people of Rome laid siege to the assembly of cardinals, shouting that the new pope had to be a Roman no matter what. ‘We want a Roman’,3 they cried, banging on the beams with sticks and brooms as a warning that they would not tolerate a foreign pope who might move the Holy See away from the Eternal City again. The episode speaks not only of the precarious situation in which the Church of Rome found itself and the urgent reasons that had prompted its transfer to Avignon, but also of the degradation of the old Vatican buildings, which were barely fit to house such ritual events. So the architect, Giovannino de’ Dolci, designed the new chapel in the guise of a fortified building, because its first function was to safeguard the Vatican’s governing body from the overbearing behaviour of the Romans – barons and populace alike. Its walls were massive and impenetrable, with high windows that barred entry and made it safe for cardinals to hold meetings, protecting them from the threatening incursions of the Roman barons, who would not have hesitated to use force in order to sway the pope’s election.

The measurements of the new chapel – 40.93 metres long, 13.41 metres wide, and 20.70 metres high (plate 1) – echoed those of the medieval building, which in turn reflected the dimensions and simple proportions of Solomon’s temple: the length was three times the width, and the height half the length. What Pope Sixtus IV had done was to change the height of the chapel, but not its floor plan. It was a decision based on the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, a building that the pope had perhaps visited as a young man.

The building work started in 1477 and was supervised by Giovannino de’ Dolci, and the architectural structure was largely dictated by the fashion of the time. The side walls were divided into three horizontal bands by large cornices. The upper one was wide enough, like a gallery, for someone to walk along it and secure the maintenance of the windows, while the vertical divisions were created by Corinthian pilasters, which formed six bays and supported the corbels of the barrel-vaulted ceiling. But it was in the roof that the building presented a highly original solution. The wide chapel was spanned by a barrel vault supported by pendentives and spandrels that, by linking to the vertical pilasters, formed blind lunettes above the large windows in the north and south walls of the building. Pier Matteo d’Amelia, a painter from the Umbrian hinterlands north of Rome, had painted the vault as a starry sky, which provided a strikingly practical solution to the difficult undertaking of decorating such a complex and intricate structure.

There remained the problem of decorating immense wall spaces, on which it was important to display the political and religious manifesto of the combative Sixtus IV and his nephew, Giuliano della Rovere, the future Pope Julius II. The latter had been prominently depicted in one of the most powerfully symbolic paintings of the Della Rovere papacy: Sixtus IV Appoints Bartolomeo Platina Prefect of the Vatican Library, painted by Melozzo da Forlì in 1477 for the new Vatican Library.4 Such a dignified presence was intended to highlight Giuliano della Rovere’s central role in the cultural policy of the papacy of his uncle, who did not seem that interested in art.

The structure of the chapel lends itself particularly well to a pictorial cycle, so much so that many scholars have dwelt on the question of its conception and have wondered whether a painter (perhaps Melozzo da Forlì) could have worked with Giovannino de’ Dolci from the outset, to ensure that the architecture was suited to a clear pictorial narrative. But the division of the walls into three horizontal bands was a well-established custom in many large churches, both in Rome and across Italy; a similar decorative scheme had been used, for example, in the old basilica of Saint Peter’s and in the basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls. Even the vertical sequence of painted hangings on the lowest level, narrative scenes in the second order, and gallery of popes’ portraits in the top order was not new. Painted drapes below a narrative sequence could be found in Santa Maria Antiqua in the Roman forum, a model that had inspired the whole classicist revival in Rome, while slightly further away, in Sant’Urbano alla Caffarella, projecting vertical pilasters were used to divide the walls into bays. Modern, on the other hand, was the lexicon of decorative architectural features – the graceful Corinthian pilasters, ornamented with grotesque motifs and echoing those that Melozzo had used a few years earlier to frame his extraordinary fresco of Platina’s appointment as librarian, which had instantly become a statement of the classicizing taste of the Della Rovere popes.

Once the ceiling decoration had been completed at the tail end of 1480, it was necessary to move on to the walls, and very quickly. The urgency of the situation dictated a rapid execution, but it was not easy to find a painter capable of completing such a task in a short a time.

Notes

1.

On the history of rebuilding the Sistine Chapel, see F. Buranelli and A. Duston, eds,

The Fifteenth Century Frescoes in the Sistine Chapel

, Vatican City: Edizioni Musei Vaticani, 2003, with two chapters: P. N. Pagliara, ‘The Sistine Chapel: Its Medieval Precedents and Reconstruction’, pp. 77–86, and A. Nesselrath, ‘The Painters of Lorenzo the Magnificent in the Chapel of Pope Sixtus IV in Rome’, pp. 39–75. For the complex ceremonial function of the chapel, see the fundamental study by E. Steinmann,

Die Sixtinische Kapelle

, vol. 1, Munich: Bruckmann, 1901 and that by J. Shearman, ‘La storia della Cappella Sistina’, in

Michelangelo e la Sistina: La tecnica, il restauro e il mito

, ed. by G. Morello and F. Mancinelli, Rome: Palombi, 1990, pp. 19–28.

2.

Nicolaus P. III fieri fecit palatia et aulam maiorem et cappellam et alias domus antiquas amplificavit pontificates sui anno primo

; Steinmann,

Die Sixtinische Kapelle

, vol. 1, p. 13.

3.

Pagliara, ‘The Sistine Chapel’, p. 77.

4.

On the fresco, see the essential documentary study by J. Ruysschaert, ‘Sixte IV fondateur de la Bibliothèque Vaticane et la fresque restaurée de Melozzo da Forlì (1471–1481)’, in

Sisto IV e Giulio II mecenati e promotori di cultura: Atti del convegno internazionale di studi. Savona 1985

, ed. by S. Bottaro, A. Dagnino, and G. Rotondi Terminiello, Savona: Soprintendenza per i beni artistici e storici della Liguria, 1989, pp. 27–44.

2A CONSORTIUM

The pope was in a hurry to finish the whole lower area of the new chapel as an affirmation of his political programme. Indeed, his haste was such that he decided to commission not one artist, or even two, but a consortium. Everything had to be ready within just one year. No proper contract was drawn up, but a very unusual series of conditions were applied. Four leading artists from central Italy were summoned, namely three from Florence and one from Umbria, and in any case the latter was familiar with Tuscan practices, having spent several years in the area during his training. The artists were Cosimo Rosselli (1439–1507), Domenico di Tommaso Curradi, known as Il Ghirlandaio (1449–94), Alessandro di Mariano, known as Botticelli (1445–1510), and Pietro di Cristoforo della Pieve, known as Perugino (1448–1523). They were commissioned to paint four large frescoes on the chapel walls, as well as the portraits of the popes above and the fictive drapes below. The four quadroni or large pictures were then assessed by a papal commission, whose report is dated 17 January 1482. The commission declared that the four paintings had been executed to a professional standard, but also that they could be valued at the relatively modest price of 250 ducats each, and this included not only the narrative scenes but also the papal portraits and the drapes of mock fabric:

The said masters are to receive from Our Holy Lord the Pope, for the said four stories together with the said drapes, the cornices, and pontifical portraits, for each and every story, two hundred and fifty cameral ducats at a rate of ten carlini for each ducat and for each story, as above.1

For almost two hundred years, scholars have debated the sequence of the two surviving documents relating to this undertaking. The first, dated 27 October 1481, records the commission received by the four painters to produce ten figurative scenes whose cost would be evaluated at a later stage:

namely, work has started on ten stories from the Old and New Testaments, with drapes in the lower part [inferius], to be painted as faithfully and diligently as they can, by each of them and their workshops.

The second document, cited earlier, values the cost of the four paintings, which had been finished by January 1482, or were at least at a sufficiently advanced stage for an evaluation to be made. On the one hand, it seems unlikely that between October 1481 and the following January the artists could have completed such a large area of fresco. On the other, the mention of just ten paintings commissioned in October suggests the likelihood that the four paintings valued in January were commissioned earlier, given that fourteen were painted in all. These ambiguities have given rise to a wide range of hypotheses, all linked to the fundamental question of who acted as the leader of the group and who decided the sequencing of the scenes. Only by retracing the practical organization of the work and of the worksite – aspects that, oddly, have been completely overlooked until now – can we attempt to answer these questions.

By reconstructing the events related to the organization of the work, and especially the problems linked to the scaffolding (a pivotal aspect), we find good grounds for asserting that a first commission was given to the four painters already in the summer of 1481 and that in October of that year, according to the surviving document, they were asked to fresco a further ten quadroni. The value of the latter was established in January, but is unlikely to have come as a surprise. Indeed, there was a well-established market for paintings and the prices moved within a very narrow range, being affected not by the quality of the painting but more by the quantities of precious materials used in the frescoes, as well as by the costs of labour and scaffolding. This sequencing corresponds to a description that indicates the operating procedure and a technological world determined by the historical context. The four painters were responsible for the finest execution of a work that was, for the most part, conceived by others.

In short, the two documents should be read as follows: the initial commission to the four painters was given in the summer of 1481 and referred to four large fresco paintings. The second commission, for a further ten quadroni, was then awarded in October that year; and in January, when the first four were finished, the actual price was confirmed.

The main value of the commissioning document dated October 1481 – which is signed by both Giovannino de’ Dolci, ‘building supervisor’, and the painters – lies in its description of the decorative theme of the chapel (ten stories from the Old and the New Testament) and in the commitment to finish the stories by 15 March the following year. This was an extraordinarily short time, considering that each painter would have had under four months to complete a painted area of one hundred square metres containing dozens of figures, each of which, even with a good dose of optimism, would have required at least four days.

This tight schedule reflects the exceptional haste, nothing short of a fury, that consumed Sixtus IV, pressing him to finish a work that was evidently at the forefront of his mind and of his nephew Giuliano’s, who was already an active patron of the arts. The pope wanted to decorate the most important chapel in Christendom within the shortest possible time. He clearly felt the need to offer a visible testimony of the power of his theological arguments in this symbolic setting. Mehmed II’s death in May 1481 had freed the church and Italy from the ever present threat of an invasion, but it also urged closing the ranks against any renewed advance of the Ottoman Empire.

The sequence of the documents also reveals another important detail, which is usually overlooked in the interpretation of the Sistine Chapel, namely that the haste was also linked to the presence of a huge scaffolding, which had been used to build and decorate the ceiling and now needed to be put to use as rapidly as possible to paint the walls. The height of the building, some twenty metres from floor to ceiling, presented a series of problems that were not easy to solve when it came to the scaffolding, which had to allow a team of painters to work comfortably. Erecting such an imposing structure was more than a matter of days and, above all, would have required planks, beams, and good-quality ropes. All these materials were already present in the chapel but would have had to be reassembled, since the scaffolding used for the ceiling was different from that required for the walls. The scaffolding for the vault needed only a flat surface at the top, at a height of around eighteen metres. Instead, to paint the figurative scenes on the walls, flat working surfaces were required at a height of around 1.8 metres. The availability of such extensive scaffolding already on site must have prompted the pope to use not just one but four teams of painters, given that the scaffolding costs had already been amortised for the ceiling. If such a large-scale structure had not already been available, perhaps the history of the Sistine decoration would have been different. A structure might have been built that sufficed for one workshop, and the execution itself would also have been slower, offering a greater guarantee for the stylistic unity of the decoration.

Note

1.

The contracts are in Nesselrath, ‘The Painters of Lorenzo the Magnificent’, pp. 69–70.

3THE STARRY CEILING

The presence of the scaffolding should also close another matter that is still debated in the literature, namely whether or not Pier Matteo d’Amelia had, in those final months, painted the vault with golden stars against a blue background. A drawing of this decoration survives in the Uffizi, and it is attributed to Giuliano da Sangallo; but a comment in the margin reads: ‘The vault for Sixtus by Pier Matteo d’Amelia. This was no longer done.’1 Although this comment has led many scholars to regard the drawing simply as a project, it is worth noting that it certainly does not give that impression but looks like the record of the outcome. In my opinion, it would have been inconceivable to start painting the walls if the ceiling had been unplastered and undecorated. Not only would the grey, unfinished state of the vault have detracted from and impoverished the decorations below it (which the pope wanted to be full of gold leaf and ultramarine blue), but painting the ceiling afterwards would have risked damaging the wall frescoes. We know of no examples where walls were painted before the ceiling: the fresco technique calls for coarse materials such as pozzolana, water, and pigments that would have risked smattering the paintings beneath.

All in all, given the immense scale of the undertaking, the practical steps and methods used in the construction and decoration of the Sistine Chapel must be kept in mind, because artistic production is a complex process and cannot be reduced to a series of abstract problems exclusively confined to style, iconography, and iconology. It is important to try to imagine how the work was carried out also in terms of an economic logic, which is always pivotal to artistic projects. To take down the scaffolding without decorating the ceiling and to leave that for later would have entailed an enormous increase in costs. It would have been equally inconceivable to spend large sums of money to reinstall the scaffolding just for the sake of painting the walls, and they would have looked insignificant against a coarsely plastered ceiling. Therefore, when interpreting the style of the paintings by the four artists, too, it is important to remember that these narratives were intended to be seen under a star-spangled blue sky. The fact that the scaffolding structure was already in place would also have brought down the costs of manufacturing the paintings, and this explains the modest price calculated for the frescoes. If the painters had had to supply and install the scaffolding themselves, the cost would have been at least 30 per cent higher.

So the timing of the decoration was closely related to the progress of the building work. Moreover, the choice to award the commission to four painters was unusual, but not unprecedented in fifteenth-century Italy, and reflects a world, that of painting, which was still intimately linked to craftmanship. Above all, the work could rely on close supervision from someone who had an overview of the narratives, and this could be only the pope himself, helped by his nephew Giuliano, who was already renowned for his appreciation of art.

The painters were asked to complete in a very short time span a product whose material difficulties were regarded as much more challenging than its creative complexity. As was usual in those days, the calculation of expenses included the lime, the cost of scaffolding, and the pigments, especially the most expensive ones, such as lapis lazuli and gold leaf, which together might amount to 30–40 per cent of the work’s value, unless the patron himself undertook to supply them – as was certainly the case here. Once the programme had been decided and the preparatory drawings accepted, the actual execution was not that different from that of a work in wood or a relatively complex building project. The painters were required to decorate the walls almost as if an upholsterer had covered them in the finest fabrics, and only the wish to convey a theological and political programme urged the pope to choose one rather than the other. The value of these decorations by comparison to other kinds of decorations, purely material (fabric, leather, inlaid wood), was only just becoming evident, and this offered a notable propaganda advantage in the political battles of the day.

The four painters were invited to work melius quo poterunt [‘better than they will be able to’], a contractual clause equivalent to the formula ‘to the best of their ability’, which still appears in craftmanship contracts. Furthermore, they had to do their best in a very short space of time. The aim was to decorate the Sistine Chapel using an overall design, and in a form that had to look as homogeneous as possible, as if it had been done by one man. The painters also had to use their skill to solve the breakdown of the narrative created by the bays along the walls. Vertically, the walls were divided into three levels and, starting from the lowest, these were filled with painted drapes of fictive fabric, then with the stories themselves, and, at the top, with the portraits of the popes. Horizontally, the walls were divided by pilasters, which were painted in the first two levels, and then projected at the third level: both the real and the fictive pilasters, with their colours, had to be absorbed into the narrative.

The names of the four painters and an analysis of their works certainly help us to understand why these particular ones were chosen, considering that they had to execute decorative work melius quo poterunt within a short time span. What did Rosselli, Ghirlandaio, Botticelli, and Perugino have in common to make them the right choice for such an important task?

First and foremost, they were all middle-aged. Almost all of them had been born before the mid-century, so they were around forty; they were in their prime, in that they had acquired extensive professional experience, yet were of an age at which they could still work directly with their own assistants and cope with the strain of working on the scaffolding, which was certainly not an easy place to be. This group of masters in their forties were ready to spend six months on the precarious wooden structure with their best pupils, and they could draw on a wealth of experience, both technically and creatively, to ensure that the results would be entirely predictable – as indeed they were.

The four painters had received a similar training in both technique and style. They had learned or perfected their art in the workshops of Florence. In the mid-fifteenth century, these were certainly the most technically advanced in the art of fresco, which was the type of painting best suited for monumental decorations, but also the one most difficult to execute, particularly in circumstances where the natural unevenness of the materials used could easily be aggravated, as in the Sistine Chapel, by each workshop’s particular usage and by the methods of application. And yet even today, when we enter the Sistine Chapel, we have the impression of seeing the work of a single team, so uniform was the result.

The distribution of the work was not even, also because the fourteen stories could not be divided by four, and there are still doubts regarding the authorship of individual scenes whose attribution is not unanimous. Two more factors complicate the attribution. Two of the scenes, those behind the altar – the Birth of Christ and Moses in the Bulrushes – were destroyed in 1534, to make way for Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, and it has proved impossible to identify the painters solely on the basis of surviving documentation. The second factor that makes the attribution of individual panels difficult is the presence of other famous artists apart from those named in the contract. According to Vasari, Luca Signorelli, Biagio d’Antonio, Pinturicchio, and others worked in the Sistine Chapel, too. Perhaps they were assistants to the other masters, or perhaps they were employed in a form of ‘subcontracting’ arrangement that gave them some autonomy. Whatever the case, we do not know exactly how the work was distributed. Yet by cross-referencing stylistic details (still a significant line of study for the analysis of paintings) with hypotheses regarding the methods of execution (an equally important point of reference), we can make educated guesses regarding the chronology and authorship of the works.

Note

1.

The drawing is in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi in Florence. Many scholars have questioned Pier Matteo d’Amelia’s part in the decoration of the ceiling but, as Shearman, ‘La storia della Cappella Sistina’ (p. 26) has stressed, there can be no doubt about his role because documents exist to prove it. Moreover, it is frankly hard to see how anyone could claim that a vault in such an important chapel was left for thirty years, simply covered in coarse plaster, while the walls below were covered with the richest decorations and filled with gold leaf and lapis lazuli.

4EVALUATING THE FOUR PANELS

Various hypotheses have been put forward regarding the progress of the work. Some are highly authoritative, yet this does not make them plausible. Ernst Steinmann, the greatest scholar of the Sistine Chapel, suggested that some panels were assigned to painters after the conclusion of certain important events for the papacy, so that they could be alluded to in a triumphalist key. Although not surprising in a late nineteenth-century scholar, such an interpretation, skewed as it is towards an idealistic reading of the work, takes no account of the practicalities that would instead become all-important to later scholars. For example, Steinmann deemed that the drowning of the pharaoh’s armies in the Red Sea was painted only after the pope’s victory against the duke of Calabria. But this suggestion does not seem viable, because the iconographical programme must have been established before the work started.

If we go back to the document of January 1482, we know with certainty that an evaluation was made of four paintings executed by individual masters. Common sense tells us that, on the basis of the economic criterion that underpins the analysis of works of art, these four paintings must have been close to one another and in sequence. We can hardly imagine that the pope would have installed four separate scaffoldings in four different areas of the chapel. All four panels must have been executed with the help of a single scaffolding structure