6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

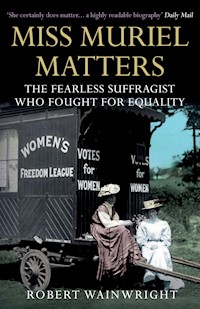

In 1908 Muriel Matters, known as 'that daring Australian girl', chained herself to an iron grille in the House of Commons to demand votes for women, thus becoming the first woman to make a speech in the House. The following year she made headlines around the world when she took to the sky over the Houses of Parliament in an airship emblazoned with 'Votes for Women'. A trailblazer in the suffrage movement, Muriel toured England in a horse-drawn caravan to promote the cause. But feminism was just one of her passions: Muriel's zeal for social change also saw her run for Parliament, campaign for prison reform, promote Maria Montessori's teaching methods and defend the poor. In this inspiring and long-overdue biography, bestselling author Robert Wainwright introduces us to an intelligent, spirited and brave woman who fought tirelessly for others in a world far from equal.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

To my daughters Rosie and Allegra,their generation and those to come

Contents

Prologue

1. The Cow Lady of Bowden

2. Role Models and Inspirations

3. ‘The Woman Question’

4. The Stage Beckons

5. First Love, First Vote

6. London Bound

7. Art and Life

8. The Pankhurst Factor

9. A Wonderful, Magical Voice

10. An Agitator is Born

11. Miss Matters Goes Vanning

12. Tillie

13. A Poetic Licence

14. Chain Gang

15. Heroine of the Grille

16. Holloway

17. A Pair of Divas

18. Muriel Takes Flight

19. Acclaim Across the Atlantic

20. Rice, Potatoes and Sods

21. A Voyage Home

22. Flesh and Blood, Bricks and Mortar

23. The Fiance

24. Pilgrims and Guerrillists

25. A Husband

26. War and Peace

27. Mother’s Arms

28. A Measure of Justice

29. A Final Journey Home

30. An Unconventional Candidate

31. Oliver

32. A Window by the Sea

Notes on Sources and Acknowledgments

Endnotes

Picture Section

Index

List of Illustrations

Muriel Matters’ growing fame as an elocutionist and a society beauty in the late 1890s made her the ideal candidate for newspaper columns sponsored by beauty products.Muriel Matters Society

The village of Bowden (looking north-west) shortly before Muriel’s birth in 1877. The bushland, so dominant when her grandparents arrived 25 years before, had given way to cottages and workshops, as the population of Adelaide expanded.State Library of South Australia

Muriel’s onstage costumes in London were as extravagant as her dramatic renditions. This photo was taken in 1908 at one of her last performances before she joined the women’s suffrage movement.Muriel Matters Society

Leonard Matters, Muriel’s younger brother, served during the Boer War before becoming a journalist, world traveller and author. He supported his sister in her 1924 bid to become one of the first women elected to the British Parliament before becoming an MP himself in 1929.Muriel Matters Society

This 1906 postcard was typical of the mindset against woman in the early years of the twentieth century - the notion that they were incapable of mixing domestic life with politics.Alamy

This poster was produced by the National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage around 1910. A number of anti-suffrage organisations arose in response to the growing suffragist support base spurred by membership drives such as the caravan tour led by Muriel.Muriel Matters Society

The Women’s Freedom League badge in its colours of green, white and gold.Wikimedia Commons/LSE Library

Muriel Matters, with her trained voice and engaging presence, quickly became one of the best-known faces of the suffrage movement. She appears here in a promotional postcard produced by the WFL.Muriel Matters Society

The WFL caravan arrives in Tunbridge Wells in Kent. It was here that Muriel met her closest friend, Violet Tillard.Getty Images

The House of Commons chamber with the Ladies’ Gallery visible above the Speaker’s chair. Muriel launched her protest from one of the central Grille panels, which had to be removed. Ironically, the panels were the only part of the chamber to survive a German bombing raid during World War II.Public domain

A belt of the type used by Muriel to chain herself to the Grille. Such belts were adapted from leather restraints that were widely used in psychiatric institutions.Museum of London

British media responded mostly positively to Muriel’s Grille protest, painting her as a heroine of the women’s movement. This dramatic full-page illustration of the protest appeared in The London Illustrated News a few days later.Alamy

Muriel – prisoner No.36 in Second Division – in her prison garb.Muriel Matters Society

The commemorative badge presented to Muriel upon her release from Holloway Prison. Her initials and dates of her incarceration are on the reverse.Muriel Matters Society

Muriel was known to draw crowds in their thousands – supporters and foes alike – when she spoke outside at public meetings, dodging missiles and insults. This photo shows her addressing a crowd in the Welsh town of Caernarfon in late 1909.Muriel Matters Society

Muriel’s return to Australia in 1910 was greeted with great fanfare and packed theatres, including the Royal in Adelaide, as ‘that daring Australian girl’ told her stories of derring-do.Muriel Matters Society

Trail-blazing female photographer Lena Connell captured Muriel’s serene composure and presence in this 1910 portrait.Mary Evans Picture Library

Plays by groups such as the WFL and the Actresses Franchise League became important fundraising and propaganda tools during the suffrage battles. In November 1909, Muriel acted in and helped produce one of the more famous,How the Vote was Won, in Cardiff. The play tells of the day women across England, from workers to housewives, go on strike, highlighting their importance to the nation.Mary Evans Picture Library

Muriel, her scarf wrapped around her head to hold her hat in place, puts on a brave face as she waits for the airship pilot to start the faulty engine.Getty Images

A newspaper photograph of Muriel’s airship as it set sail from Hendon towards Westminster. Unfavourable winds would blow the airship off course but the protest would make headlines around the world.Muriel Matters Society

Muriel discusses tactics with fellow WFL member Edith Craig as they walk down Whitehall toward Downing Street, probably in 1909, to make yet another attempt to be seen by the Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.Muriel Matters Society

The children at the Mother’s Arms school in East London, probably the first attempt to bring Montessori teaching principles to Britain.Muriel Matters Society

Muriel’s pragmatic teaching methods engaged children not only in the classroom but also their everyday life, from helping in the kitchen to table manners.Muriel Matters Society

Muriel, with her wide blue eyes, golden hair and engaging presence, was the antithesis of the mainstream media’s caricature of suffrage protesters as ugly spinsters with no hope of finding a husband.Muriel Matters Society

Muriel pets a family dog, most likely during her 1922 visit to Australia.Muriel Matters Society

A reunion in 1928 of prominent suffragists and suffragettes on the tenth anniversary of the passing of the Representation of the People Act, which enfranchised women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications. Muriel is at the centre of the back row, with Teresa Billington-Greig to her right. Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence is second from left in the front row, next to Sylvia Pankhurst.Muriel Matters Society

Although she faded from view during her later years, Muriel’s deeds in the suffrage movement were never forgotten and on occasions like this in the 1950s, journalists would visit her in Hastings to hear her recount her adventures.Muriel Matters Society

Muriel’s house (right) overlooking the seafront at Hastings where she lived for the last two decades of her life.Alamy

PROLOGUE

The woman in the thick green coat and jaunty driving cap stamped her feet and danced in circles. To the huddle of reporters and photographers watching nearby, it looked like some sort of crude flamenco, but Muriel Matters was simply cold, and probably a little nervous, and a little jig might just keep her warm.

It was just after 1.00 pm on February 16, 1909 and the temperature hovered around freezing by the banks of the Welsh Harp Reservoir near Hendon in north London. Despite the cold, the journalists and a clutch of onlookers had gathered to watch an historic moment in political campaigning and the fledgling world of aviation.

Although the area had been used on and off for fifty years by aeronautical companies for experimental flights, scientific journeys and even tethered balloon rides for picnickers, this would be the first time that a powered aircraft had taken off from the green expanse that would become integral to the city’s wartime defences.

And a young woman whose feet had never left the ground was preparing to take to the skies. The plan to drop hundreds of ‘Votes for Women’ leaflets on the head of King Edward VII as he sat in his golden carriage trotting down The Mall to open the new session of parliament seemed crazy. But what a story!

Like many historic moments, opinion would be divided about its sanity. Was this lady naive, reckless and foolhardy or a brave crusader? In truth, Muriel Matters fell somewhere in between; the thrill of the ride and the sense that what she was doing was necessary and would make a difference to others was more powerful than the fear of physical harm.

It would be 5 degrees cooler once they were aloft, hence the layers of heavy clothes beneath Muriel’s coat. Other than the cold, though, the weather was favourable: bright, clear skies with a forecast of light to moderate winds out of the north – hence the need to take off from this side of the Thames. It would have been impossible to take off south of the river and try to fly into the prevailing wind toward the city. Even Hendon wasn’t perfect, lying slightly north-west of the city centre, but there were few possible launch sites, highlighting the nascent and precarious nature of aviation.

Muriel looked over toward the airship, stretched out like a cigar with what appeared to be the foresail of a yacht at the rear to act as a rudder. The balloon was adorned with the slogan Votes for Women in huge lettering, so it could be seen from the ground, and streamers in the Women’s Freedom League colours of white, gold and green would trail behind.

The framework beneath the balloon was a different matter, a skeletal scaffold of wires, ashwood and bamboo with a wicker gondola slung in the middle barely big enough for two people to squeeze into. Comfort was not an option in a design for as little weight as possible.

She focused on the man scurrying around the airship. Henry Spencer, the pilot, looked a bundle of nerves checking the struts and ties and engine, which seemed tiny for its job of driving the airship in a series of yacht-like manoeuvres across the prevailing winds to position it over the Houses of Parliament as the King’s procession made its approach.

As she watched and waited, Muriel might have reflected on her incredible life transformation. It seemed only yesterday that she was in the city of Adelaide on the other side of the world, enjoying the plaudits of critics as an aspiring actress, an elocutionist who could hold the attention of audiences for hours as she recited great dramatic verses. She had travelled across the world in pursuit of those dreams, had been welcomed in some of London’s great entertainment venues but then decided she had a greater calling than footlight fame, a calling for which she was prepared to risk her life.

It was almost 1.30 pm, lift-off time if they were going to get south to Westminster and greet the King’s carriage. Several men moved forward, loaded the bundle of pamphlets and then lifted Muriel into the basket while a dozen more clung onto ropes attached to the framework to steady the ship.

But there was a problem. The motor wouldn’t start. All Muriel could do was busy herself, stacking the pile of pamphlets neatly and fastening her hat to her head with a scarf tied beneath her chin. She smiled and posed for the cameras, a megaphone clasped casually in gloved hands. In the background Henry Spencer looked on anxiously.

Finally, after furious minutes of tinkering, the engine spluttered into life and the giant ship lifted slowly into the air. Muriel Matters had taken flight.

1.

THE COW LADY OF BOWDEN

Mary Matters, a widow with four children and an ageing mother, wrote asking permission to depasture her cow on the parklands free of charge. Communications favourable to the request were received from Mrs Gawler and Dr Whittell. Referred to finance committee.

– South Australian Register, August 10, 1862

The request made of the Adelaide Municipal Council seemed reasonable enough. Even a neighbour, a Mrs Gawler, and a respected GP, Horatio Whittell, a man of ‘high character, integrity and ability’, according to the same newspaper, felt compelled to support Mrs Matters’ case for recognition of hardship, but the men of the council took a different view.

As trifling a matter as it appeared to be for a council in charge of a growing city, the widow’s request was shunted off to a committee where it would be denied out of hand, the august body of gentlemen deaf to the plea of an enterprising woman with no husband that she be allowed to feed her only asset – a cow – on public land, even though it would help keep the grass down.

It was a mean-spirited decision by the male political elders of a colonial city supposedly rooted in a spirit of entrepreneurial endeavour and equity. The travails and challenges of a widow seemed to have no bearing on their considerations. If anything, it annoyed them that a woman would seek to challenge laws enacted by men.

Adelaide, capital of the freely settled colony of South Australia, had been founded less than three decades before, designed by the Surveyor-General Colonel William Light in a grid pattern on either side of the Torrens River: broad avenues, narrower streets and public squares surrounded by great parklands filled with trees that would help keep the air clean, in contrast to the poor light and dank, polluted air that permeated most overcrowded European cities.

The genius of Light’s design was matched by the utopian impulses fuelling both his garden city’s construction and the settlement of the colony. Adelaide was not to be built on the back of convict labour, like the east coast capitals of Sydney and Melbourne, but as a free settlement, financed by selling investment parcels of land to the wealthy in faraway Britain. The proceeds from the sales (to largely absentee landlords) would fund the cost of shipping a ready-made working-class population from the United Kingdom to build the new city.

‘The great experiment in the art of colonisation’ was considered an immediate success. The initial land release sold quickly and a campaign was launched in London to lure settlers across the seas with promises of a paradise: a new society that championed civil liberties, tolerance and religious freedom, far from the human crush and crime-filled streets of the Mother Country. So bright was this beacon that no jail had been planned, let alone built, for the city named by William IV after his German wife.

Free passage was offered to men aged under forty-five, single or married, who were skilled farm labourers, shepherds or copper miners, interested in living and working in the rich agricultural regions opening up outside the city. There was also room for men good with their hands who could help build the city that was fast rising from the riverbanks – bricklayers, stonemasons, farriers, gardeners, sawyers, carpenters, mechanics, wheelwrights and the like, provided they were ‘sober, industrious, of general good moral character … free of all bodily and mental defects’.1

Women were welcome too, single or married, particularly those with experience as domestic servants, farm girls, plain cooks or nurses. A letter from the Bishop of Adelaide offering advice to emigrants to the colony painted a rosy picture: ‘Wages are high and there is no fear of starvation,’ he wrote. ‘Respectable servant girls are sure to find employment.’ There was even the enticement of land ownership, via a scheme under which a man could buy his own plot of land and put aside wages to pay it off.

In 1852, Mary Matters and her husband, Thomas, heeded the call, leaving a settled if crowded life in the port city of Plymouth to start afresh. Thomas was a 32-year-old stonemason with the ideal combination of youth and trade experience required in the fledgling community.

His wife, although six years older, fitted the criteria for ‘acceptable’ women. Mary was the eldest of twelve children of a struggling Devon farm worker. With little chance of an education, she had followed her mother into domestic service and helped raise her siblings, and was thirty-three before she found a husband.

The marriage certificate sheds no light on how Mary Adams met Thomas Matters. They lived in towns fifty kilometres apart and their families had no obvious connection. The only link appears to be religion, both families being devout followers of the Methodist philosophy of John Wesley. It would be a driving moral force for several future generations.

Mary had only stopped working after the birth of her third child, a daughter to follow two sons, which meant financial pressure was growing as much as the family’s need for space, crammed as they were into three rooms of a five-room house near the city docks. A fresh start seemed a godsend and too good to refuse, even if it was on the other side of the world.

Mary wasn’t the only member of her family to emigrate. A younger brother, John, had already left for South Australia, and three unwed sisters and her widowed mother would follow a few months later. Another brother would settle in New Zealand and a third in Victoria.

On August 24 Thomas and Mary packed their children – Charles, Thomas and baby Mary – along with a small bundle of clothing and personal effects and joined 339 other souls aboard the three-masted barque Sea Park to set sail for the unknown.2 It was the seventy-ninth such government-funded ship to make the trip carrying the future citizens of Adelaide, whose population now stood at about 50,000. Most of the family’s belongings had to be left behind, traded for a new beginning. They would never return.

* * *

Mary had turned forty by the time the family stepped ashore in Adelaide almost four months later. Port Adelaide, where the Sea Park lay at anchor, must have appeared a little like Plymouth, with its bustle and grime, but nothing else gave the family any sense of being in the soft environs and gentle light of England.

They had arrived in the early heat of an Australian summer, into a landscape they could not have imagined with its open spaces, wild glaring skies and remorseless sunshine. Here the roads were dry and dusty, the fine, pale sand blown by hot, swirling winds. Men working outside hid beneath large straw hats to keep the baking sun from their faces and spoke with a strange ‘independence of manners’, a frankness that jarred British sensibilities.3

Yet it was clearly a place of prospect and plenty, the storehouses in the centre of the now bustling city stocked with an abundance of fruit and vegetables – grapes, tomatoes, plums, peaches, apples and more. The talk in the streets was of opportunity rather than hardship, and of mineral and grazing riches beyond the blue-grey hills that ringed the mangroves and the coastal plain on which the city had been so carefully placed.

It was also a blessed relief to be free of the squalid living conditions and putrid food aboard ship, for there was great sadness amid the excitement and anticipation of their arrival, a few weeks before Christmas. Mary’s infant namesake daughter was among the fourteen babies and young children who had died from infection and illness at sea. By contrast there had been nine births.

And Mary was pregnant again, the conception almost certainly occurring on August 23, the night before the family sailed from Plymouth – a celebration of a new life ahead in so many ways.

The welcome was promising. In the first days after arrival, families like the Matters were housed in cottages along the harbour foreshore and the ‘Stranger Friend Society’ was on hand to relieve distress among the newly arrived. It all seemed too good to be true. Thomas secured work within days, and the family leased a house constructed of pisé, a form of rammed earth, with a dirt floor and tin roof, in the village of Bowden on the northern fringe of the city. The small outpost had been roughly cleared and chopped up into irregular lots set along nameless streets.

The lease came with the inducement of the prospect of securing a mortgage to buy the modest, four-room house, squeezed onto its tiny allotment, perhaps as small as one-sixteenth of an acre and sized to maximise profit for its developer rather than create amenity for the lessee. The Matters’ neighbours were labourers and tradespeople: tanners, millers, lime-burners and bricklayers with skills but little money, grateful for the work and security that sprang from a city still largely under construction.

Few would make the change from lessee to landowner. A developer named Eckley owned 117 properties in Bowden and the rest were held by half a dozen individuals. Families made the homes their own by planting fruit trees and vines and digging tiny vegetable plots into the bushland, creating a little Europe amid the native wattles and gums, mallees, myrtles and quandongs. Pigs and goats wandered freely in the village that soon had five hotels, a dozen stores, a collection of brickworks and tanneries and even a modest schoolhouse.4

In May 1853 Mary gave birth to a third son, John Leonard, a renewal of sorts and an event that went some way to ease the pain of her baby daughter’s death. But life was fragile and the fates cruel. In February 1857, barely four years after arriving in the colony, Thomas Matters was dead from gastric fever. He was just thirty-seven. The funeral notice would say it had been sudden, the stonemason passing away at home after a ‘short illness’. A fortnight later his grieving widow gave birth to their fourth child – another son. The promise of a new, wondrous life had now turned to despair.

Although Mary had familial support, resources would not stretch to financial help because her sisters and mother were living hand to mouth. Nor could her brother John, who had his own family to feed, spare any money. At the age of forty-five, with four young children and no likely marriage prospects, Mary Matters was on her own in a city that wanted contributors, not passengers.

The cow therefore took on an extra significance, bought from the little money Mary could scrape together and symbolic of her resourcefulness and determination amid the setbacks of colonial life.

* * *

On a clear, bright summer morning in late 1865, a man climbed the rickety scaffolding around the almost completed Adelaide Town Hall. He carried a heavy bag and tripod, and on reaching the top braced himself, faced north and began to take photographs. For the next hour or so, Townsend Duryea, an American mining engineer turned photographer, carefully made his way around the tower in an anti-clockwise fashion to avoid the sun’s sharp rays shining into his lens while he took fourteen photographs, creating the world’s first photographic panorama.5

The result showed the precision and success of the Adelaide experiment. Each point of the compass was dominated by a wide avenue, splitting rows of modest housing and timber-framed shopfronts, grand sandstone public buildings and neat parks of carefully planted trees that would one day spread to cover the flat landscape to help the city ‘breathe’.

But behind the innovative photography lay another, more complex story. The system of land title, so carefully plotted, had been rorted and botched in the early years of the colony and had stunted its development until the Real Property Act, which would revolutionise land ownership not only in Adelaide but around the world, was passed in the South Australian parliament.

In the distance, just beyond the range of Duryea’s camera, lay the ring of villages that would one day merge to become suburbs all the way to the sea. Among them was Bowden, where the Matters family lived, and the village of Croydon where ‘Mary Matters of Bowden’ had recently applied to have four housing allotments registered in her name under the new Torrens title system.

Croydon had been carved out of the bush by two investors who named it, as so many did, after their home town in England, but the land remained largely unsold because of the confusion about land ownership. Mary had seen her chance to acquire land cheaply and build a future for her family. Significantly, hers was the only female name on the registry.

Aged fifty, she had also established a small business run from her home, hand sewing hessian sacks that she sold to farmers to hold their produce. The business prospered, if slowly. There was more than a single cow too, the profits from sack-making poured into increasing the herd. By the mid 1860s she was described as a ‘cow-keeper’ in official documents when her animals occasionally strayed onto public verges and caught the attention of the ranger and she was dragged before the courts to face a fine of a few shillings and a lecture from a pious magistrate.

The land purchase would be a turning point in her life, and turn adversity into triumph. Through the next three decades she would buy and sell land and cottages, mainly in and around Bowden, using some to house family members and others to provide an income – ‘a good stone house of four rooms let at 10s per week’, as one newspaper advertisement would note.6

Mary would only move from Bowden in the later years of her life, buying a large house at Semaphore, within sight of the beach where the Sea Park had arrived with her young family, full of hope, more than three decades before. She had survived and thrived in spite of circumstances and social attitudes and raised four sons.

* * *

The true legacy of Mary Matters did not lie in a bank balance or a row of houses, a cow or a pile of hessian sacks, but in her determination for self-improvement, a desire apparently embedded in the religious ethos of her upbringing and carried not only into her own life but into those of her children and grandchildren.

Her father, Leonard Adams, may have been a struggling farm worker, but he was also a man of God, a follower of the founder of the Methodist Church, John Wesley, who preached personal accountability, championed social issues such as prison reform, railed against slavery in the United States and believed in a greater role for women in the Church. Mary held the same philosophies, and despite having no formal schooling herself, decided that it was important for her own children to benefit from a good education, even though, economically, sending her boys out to work would have made more sense in the early years of her widowhood.

She chose Whinham College, a school that had sprung from modest beginnings. John Whinham was a self-taught ‘educationist’ who had fallen on hard times and emigrated from England with his family in 1852. His school had begun simply enough, with a single student in a room, and would grow to be one of the most respected in Australia. At the time the Matters boys attended, it was still a relatively modest school in Ward Street, North Adelaide.

Whinham had a broad notion of the benefits of education. On his retirement, he would say: ‘In education I have two main objects in view: the first is to try to enlist the sympathies of my pupils on the side of everything that is good and noble, and the other being to enlarge and cultivate their minds in everything appertaining to political and every-day life, so that they might be enabled to discharge the duties of social and civil life faithfully and well.’7

The Matters boys would take their opportunity with both hands. The eldest, Charles, would find his way into a banking career before opening an auction house as the possibilities for land development grew. His brothers Thomas, John and Richard would join him as the business expanded.

Charles would also rise in Adelaide’s social and political circles, and would later move to Melbourne where he also made a name for himself. He stood for parliament and travelled widely in Europe, America and Japan, where he helped form the Welcome Society of Japan (Kihin-Kai) to promote international tourism with the west. Like his maternal grandfather, he took religion seriously and chaired an association of Methodist preachers. He wrote expansive articles for newspapers about his experiences and his diverse interests, which included being a devotee of the famed American horticulturalist Luther Burbank.8

Charles and, to a lesser extent, Thomas would not only have influence in an economic sense but in the social development of the city and the rights of its citizens. He and his wife, Hester Ann Jessop, would become heavily involved in the temperance movement, a favoured cause of Wesleyan Methodists.

In 1891 the couple would travel to England via America to undertake a study of social problems, particularly those caused by liquor laws. British newspapers noted the visit of the Australian contingent, mentioning their attendance at the annual conference of the Rechabite movement, which believed in total abstinence. Mrs Matters was said to have made ‘a very neat little speech’ in which she noted that a number of South Australian clubs and organisations now accepted female members, describing it as ‘another great step in the process of giving the woman equality with the man’.

During the trip, the Matters would also meet with Millicent Fawcett, a leading light of the British women’s suffrage movement, who later noted of the discussion: ‘It would almost seem that Australia will lead the way in this reform. Be that as it may, the progress on your side of the world is most gratifying and encouraging to us over here in the old world.’9

There was another who would be greatly influenced by the social reforms of the far-flung colonial outpost the Matters clan had made their home – Muriel, the teenage niece of Charles and Hester and granddaughter to Mary, the stubborn cow lady of Bowden.

2.

ROLE MODELS AND INSPIRATIONS

Illiteracy gave Muriel Lilah Matters the memorable name that would accompany her deeds in life. She would have been born with the surname Metters but for a spelling error by the priest who baptised her paternal grandfather, Thomas, the stonemason who would emigrate to Australia with his bride, Mary.

The mistake had been long forgotten by the time Muriel was born on November 12, 1877, delivered in the family cottage at Bowden. Outside, the city of Adelaide was finally beginning to fulfil its utopian promise. The Overland Telegraph had linked communications from Australia to London and the telephone was on its way; the city’s engineers had forded the Torrens River with a decent traffic bridge and horse-drawn tramways would soon dominate the city centre.

Public health was improving with the completion of new facilities, including a children’s hospital and the nation’s first sewerage system. The arts were flourishing and becoming a feature of the city’s life, as was education, with two tertiary institutions, both of which accepted enrolments from women.

John Matters was working as a cabinetmaker when his daughter was born, yet to join the family firm that would establish his two older brothers as leading citizens. His apprenticeship had been marred by a court appearance in 1872 in which he admitted using insulting language to his master, a Mr James Gibbs. It was clearly considered a serious offence in a society that demanded civility and the magistrate not only fined him £1 but warned that if it was repeated then he would be jailed. ‘Oh, all right,’ was the reported response of the young man, aged nineteen and described as ‘son of Mary Matters, widow’ as if he were still a juvenile.1

It was not his first brush with the law. At the age of ten, John had been caught hurling stones and shattering windows at an empty building near the city centre. He was fined and warned, the incident brushed off as typical of ‘lads in the habit of amusing themselves’,2 but it would be an indication of John Matters’ attitude to life; he was a gambler who struggled to settle and tended to ride on the coat-tails of his older brothers, Charles and Thomas.

On another occasion he became embroiled in a rape case as a witness and companion of the alleged perpetrator, the newspaper coverage of the case revealing the young man’s somewhat nomadic existence in which he frequently travelled to small towns outside Adelaide seeking work. Even after he married and had a family, John was known to leave home for months at a time chasing mining riches, including investing in a silver mine that, like all of his early ventures, came to little or nothing.

It was in stark contrast to the steady rise of his older brothers, not only Charles but also Thomas, who had gone into business after leaving Whinham College, forming a partnership with a friend and building and operating a chaff mill near Port Adelaide, a half day’s ride north-west of the city centre, where they produced horse feed. He later moved into civic affairs, employed as a district clerk until 1878 when he was recruited by Charles to help expand his real estate business, opening a branch in the port area of the city. Thomas would marry twice and have eight children, each announced triumphantly in the newspapers.

In 1874 John Matters had married Emma Warburton, daughter of a Welsh immigrant family. If his young bride ever had ambitions beyond motherhood they were drowned in a sea of children – five in as many years, including one death, before her husband ceased his meanderings, at least for a time, and settled down to take a job with C.H. Matters and Co. They would eventually have ten children – five girls and five boys – over twenty years,3 Emma, as resourceful as her mother-in-law, would be the stoic rock of the family, covering for her frequently absent husband whom she stood by despite his errant ways.

Although they lived barely a mile from the bustling centre of the growing city, the family’s modest cottage might as well have been in the middle of the bush. Muriel’s brother Leonard would give a sense of their childhood in the introduction to a book he would write about his own adventures as a traveller and journalist. He wrote of learning to tell the time by the passage of the sun across the sky, of wandering through ‘trackless scrub’ and climbing into the lower reaches of the Adelaide Hills, exploring ravines and caves and getting caught in landslides. His wanderings were not appreciated at home, his muddied, ragged appearance after a day of exploring alarming his ‘fond but overly anxious’ mother and enraging a father who was wont to wander himself.4

Muriel, four years older, would also have a fraught relationship with her father, an authoritarian man whose word was law, a man not to be crossed who enforced rigid rules such as excluding younger children from eating at the table until they learned Victorian manners. Unlike most of her brothers and sisters, Muriel was prepared to stand up to his anger more often than not. He would mellow with age.

In 1884 the family moved to Port Augusta, a town built on mangrove swamps and the flat, sandy plains at the top of the Spencer Gulf, three-hundred kilometres north of Adelaide. Its streets were filled with teams of camels, donkeys, bullocks and mules hauling anything from food and wool bales to rolls of wire that would be used to mark the boundaries of the great pastoral leases. Progress had been stunted by drought, but the town’s natural harbour and the fervour created by the discovery of mineral riches had ensured its survival. The Overland Telegraph had been connected in 1872 and in 1882 the railway to Adelaide was completed.

Despite its progress, Port Augusta was still something of an overgrown village when John Matters and his family arrived, and he quickly found himself elected to the local council. He established a chaff mill and attempted to promote the Matters family business, but became embroiled in several court cases, one involving alleged larceny by an employee and another claiming that a friend had borrowed and then lost one of his horses. He was unsuccessful in both matters.

But for all his shortcomings, John Matters would follow his mother’s example and ensure that his children went to school. Records show that the older children – Elsie, Muriel (then aged seven) and Harold – were enrolled at the local school in 1885 and 1886.

The school had small, stuffy rooms, poor lighting and featured a teaching style that was more about berating than instruction. Fragile funding and a rollercoaster economy meant there were frequent teacher shortages and senior students were often called upon to fill in. But it was a start, not only for Muriel and her siblings, but perhaps of her attempts many years later to ameliorate the hardships of early childhood for families with little or no money.

The family’s stay in Port Augusta would last just three years, cut short, it would seem, because of controversy over John’s questionable sale of land ‘at low tide’, the details of which were never fully explained. In 1887 they scurried back to Adelaide and the bosom of the Matters family.

* * *

In years to come Muriel would nominate a play written by the Norwegian Henrik Ibsen as a defining influence in her life. She was given a copy of A Doll’s House to read at the tender age of fourteen, when most young ladies were probably more familiar with more dutiful literary heroines, like Charles Dickens’ Amy Dorrit and Jane Austen’s Anne Elliot.

Ibsen’s play had a different message – one of independence and achievement outside marriage – and one that Muriel’s literary sponsor considered her intelligent and curious enough to appreciate, even though she was too young to attend performances of the controversial work when its production divided Australian audiences (and audiences around the world) because of its apparent nod to the women’s suffrage movement.

The three-act play tells the story of Nora, who leaves her husband and three children to discover her own identity: ‘A woman cannot be herself in modern society,’ Ibsen would explain in notes to the play, going on to say that it was ‘an exclusively male society, with laws made by men and with prosecutors and judges who assess feminine conduct from a masculine standpoint’.

Ibsen would later insist that his play was a depiction of humanity and the right to be an individual rather than any specific endorsement of the women’s suffrage campaign, which had begun to find voice in Australia. Regardless of the author’s opinions, the play would be grabbed by the suffrage movement and placed at the heart of the social phenomenon involving the ‘New Woman’ – the growing discussion about the nature and role of women in society that would spawn dozens of books and plays over the next thirty years.

The arrival in Australia of A Doll’s House in September 1889 had caused a storm of protest. Nora’s character, interpreted as noble by supporters, was seen as villainous by opponents who viewed her search for self-worth as an abandonment of her family and, therefore, her responsibilities as a woman. ‘Ibsenism is not likely to become the rage in Australia,’ one predicted. How wrong he would prove to be.

The seeds had been sown, including in the mind of a teenage girl in Adelaide. Most likely, a copy of the play was given to her by her Uncle Charles and Aunt Hester, both stalwarts of the theatre, who would have been among the audience in August 1891 when it was staged at the Albert Hall, later the rallying point for women’s suffrage meetings.

Muriel and her sisters were enrolled at the Parkside High School, which advertised, without further detail, ‘particular attention is given to a sound English education, together with all modern accomplishments’. Parkside, one of a number of small private schools that had sprung up around the city, was run by sisters Olive and Maude Newman and had clearly been noticed by authorities. Senior government ministers often attended its annual prize-giving ceremonies – where Muriel won the occasional prize but more often was the star performer of the night’s entertainment, singing, playing the piano and performing elocution: ‘Several young ladies acquitted themselves with marked success, especially Miss Matters,’ press coverage noted in 1891.5 At the same presentation, the Minister for Education, while presenting prizes, pointedly referred to changing social attitudes to women: ‘Ladies in the future, I am glad to say, will take a more prominent part in public affairs and I would encourage you to fit yourselves for the positions women are to occupy.’

Exposure to such messages, ideas and powerful rhetoric would leave a lasting impression on Muriel who, as the second eldest, would have been forced to be resourceful, helping her mother run a big household from an early age. Not only did it run counter to her mother’s lot in life, which she could not fail to notice, but it also came during a significant moment in history when the women’s movement was beginning to gain traction in her home city: ‘I will never forget my joy in finding that the sentiments I had always vaguely but keenly felt had been put into words, forcible, majestic, dignified,’ she would reflect in an interview.6

In fact, South Australian women who owned property had been given the right to vote three decades earlier, although only at local government level and without the right to stand for election.

There had been howls of dismay around the colony at the time, with some newspaper editors in Queensland and New South Wales at first refusing to believe that ‘women have voted’ in an election for the Port Adelaide mayoralty in 1863. ‘It is difficult to us in the nineteenth century to believe in the truth of such a statement as that telegraphed,’ wrote one Brisbane editor who, fearing that a woman had actually been elected to lead the council, conjured images of female riots and ‘Adelaide insurrectionists electing one of their number by force of arms’.7

The following year, women in the neighbouring state of Victoria were inadvertently given the right to vote at a state election when electoral laws granted the vote to ‘all persons’ on municipal rolls. A number of women took the opportunity, as numerous papers reported: ‘At one of the polling booths … a novel sight was witnessed. A coach filled with ladies drove up, and the fair occupants alighted and recorded their votes to a man, for a bachelor candidate.’8

But it only served to highlight the challenge that lay ahead. Rather than enshrine the ‘mistake’ in law post-election, the Victorian parliament quickly closed the loophole. It would be another two decades before women began to organise themselves politically and form the first suffrage societies, initially in Melbourne and then South Australia, just as John Matters and his family were returning to Adelaide from Port Augusta.

It was a time of significant social reform. The Women’s Suffrage League of South Australia had emerged from the Social Purity Society, a movement aimed at righting the ‘social evil’ of prostitution and the mistreatment of women. The Society’s campaign was successful in part, raising the age of consent for girls to sixteen to assist authorities in keeping girls from prostitution. The members then pledged ‘to advance and support the cause of women suffrage in this colony’.

Likewise, the temperance movement in South Australia emerged from the Christian desire to address social ills. Charles Matters was among the most vocal members of the Independent Order of Rechabites and relished taking to the stage at meetings where, as chairman, he had a reputation as a ‘forcible’ speaker. He made his views known loudly and often, as he did at church meetings where his niece was often in the audience.

Muriel’s aunt Hester was a member of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union which had been formed in Adelaide in 1886 with 57 members. At first, the group, made up largely of members of the Wesleyan, Baptist and Congregationalist Churches, targeted alcohol use and domestic violence, but its causes grew quickly as membership swelled to include the poor treatment of Aborigines, factory workers and prisoners and the promotion of women’s rights.

In 1891, just as Muriel was being entranced by Henrik Ibsen, the WCTU joined forces with the Suffrage League, headed by the anthropologist Edward Stirling, a university professor and former member of parliament who in 1885 had introduced a bill in which he proposed voting rights for women, including widows and single women, even quoting the philosopher Plato. The plea had fallen on deaf ears as would the next seven attempts.

The women’s suffrage cause would not only be opposed by indignant men, who cruelly cast the female proponents as the ‘shrieking sisterhood and gimlet-eyed’, but also by equally indignant women who argued that women’s duties in the home had been divinely ordered and could not be relieved by men, and that political equality would deprive women of unspecified ‘special privilege’.

There were also powerful opposing voices from Britain, most notably that of Eliza Lynn Linton, ironically the first female salaried journalist in Britain, a vehement anti-feminist who in the same year as the women of Adelaide began their push for suffrage would publish an essay titled ‘Wild Women as Politicians’, parts of which found their way into Adelaide newspapers:

This question of woman’s political power is from beginning to end a question of sex, and all that depends on sex – its moral and intellectual limitations; its emotional excesses, its personal disabilities, its social conditions. It is a question of science, as purely as the best hygienic conditions or the accurate understanding of physiology. And science is dead against it. Science knows that to admit women – that is, mothers – into the heated arena of political life would be as destructive to the physical well-being of the future generation as it would be disastrous to the good conduct of affairs in the present.

But the most prominent critic of all was the woman the suffragists needed most – Queen Victoria – who wrote:

I am most anxious to enlist everyone who can speak or write to join in checking this mad, wicked folly of ‘Women’s Rights’, with all its attendant horrors, on which her poor feeble sex is bent, forgetting every sense of womanly feelings and propriety. Feminists ought to get a good whipping. Were women to ‘unsex’ themselves by claiming equality with men, they would become the most hateful, heathen and disgusting of beings and would surely perish without male protection.9

If female suffrage were ever to be made law, the monarch would have to sign her name to it.

3.

‘THE WOMAN QUESTION’

Ladies poured into the cushioned benches to the left of the Speaker and relentlessly usurped the seats of gentlemen who had been seated there before. They filled the aisles and overflowed into the gallery on the right, while some of the bolder spirits climbed the stairs and invaded the rougher forms behind the clock. So there was a wall of beauty at the southern end of the building.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!