11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

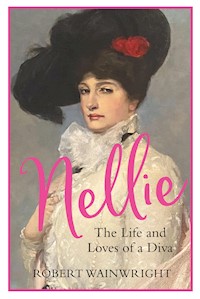

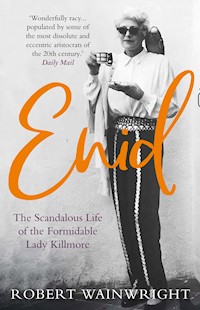

Enid Lindeman stood almost six feet tall, with silver hair and flashing turquoise eyes. She stopped traffic in Manhattan, silenced gamblers in Monte Carlo and walked her pet cheetah through Hyde Park on a diamond collar. In early twentieth century society, where women were expected to be demure and obedient, Enid Lindeman gallivanted through life accumulating four husbands and numerous lovers, her high-jinks dominating British gossip columns during the inter-war years. She drove an ambulance in World War I and hid escaped Allied airmen behind enemy lines in World War II, played bridge with Somerset Maugham and entertained Hollywood royalty in the world's most expensive private home on the Riviera, allegedly won in a game of cards. Enid bedazzled men with her beauty, outlived four husbands-two shipping magnates, a war hero and a larger-than-life Irish Earl-spent two great fortunes and earned the nickname 'Lady Killmore'. From Sydney to New York, London to Paris and Cairo to Kenya, Robert Wainwright's biography restores the remarkable Enid to thrilling, vivid life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

First published in Australia in 2020 by Allen & Unwin

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Allen & Unwin

Copyright © Robert Wainwright, 2020

The moral right of Robert Wainwright to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 91163 084 5

E-book ISBN: 978 1 76087 430 8

Printed in Great Britain

Allen & Unwin

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.allenandunwin.com/uk

For Paola. Always.

Our adventure continues.

CONTENTS

Prologue

1 Cawarra

2 An independent spirit

3 Letter from America

4 A birth and a death

5 Europe bound

6 The transformation

7 Caviar Cavendish

8 The company of men

9 A father and a secret

10 Marmaduke

11 ‘He laid the world at my feet’

12 Champagny lordy

13 A jungle romance

14 Crashing the gilded halls

15 The sting

16 An ultimatum

17 La Fiorentina

18 Looking-glass world

19 Riviera refugees

20 Resistance

21 Where there’s a will . . .

22 The fairy queen of Lees Place

23 The storekeeper’s daughter

24 The excessively large gentleman

25 The touch of death

26 The newsprint knight

27 The waiting game

28 A lie laid bare

29 From the rubble

30 Australia

31 ‘Did I really kill them all?’

32 The unflappable hostess

33 Baron of Waterpark

34 A new adventure beckons

35 The racing game

36 Home

Epilogue

Afterword and acknowledgements

Selected bibliography

PROLOGUE

August 1948

She stepped onto the main floor of the Casino de Monte-Carlo, a silver-haired seductress with turquoise eyes.

The action on the tables paused as she glided by, as if carried on a hidden conveyor belt. In a room full of the moneyed, famous and powerful, men and women alike watched in lust or envy as she made her way across the room.

It was not as if she was unknown. The lady had been here many times before and always drew attention, often for her fearless style of play as much as her looks, mature as they were. Legend had it that she had won enough playing chemin de fer, a French baccarat-style card game, one night to buy the most spectacular home on the Côte d’Azur. No one would ever confirm such a story, of course, but neither would anyone deny it in a place that thrived on mystery, splendour and excess.

On this night she was a vision to behold, almost 6 feet tall and dressed in a Molyneux gown of white lace over a pale violet underskirt that clung to her graceful curves like a second skin. Delicate appliquéd flowers adorned the dress, each holding in its centre a diamond that flashed and dazzled, catching the light from the chandeliers that hung in the centre of the room. The effect gave her an ethereal, shining beauty.

At her throat sat a three-tiered diamond necklace while her hair, cut in short, tight waves that accentuated high cheekbones, was crowned with a silver tiara dressed in pink diamonds—a gift from her third husband, Marmaduke the 1st Viscount Furness, to wear at the coronation of an English king.

The usual sounds—gamblers’ shrieks of triumph and cries of anguish—dulled for a moment, replaced by whispers of admiration or scorn. The lady divided opinion; a woman whose wealth and prominence was viewed either as well deserved or created by calculated greed. Not that she ever really cared what others thought.

The men at the main table stood as she approached. A chair was fetched and placed next to a portly man in tails. Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah, the third Aga Khan and spiritual leader of 15 million Ismaili Muslims, and one of the richest men in the world, smiled at her arrival.

‘My dear Enid, could you not be more discreet with your entrance? Next time please come in black so I might be allowed to get on with the game without the undoubted distraction that your presence at my table is going to create. Allah should have made you a good Muslim and then you would have arrived smothered in veils.’

Lady Kenmare, the former Miss Enid Lindeman of Strathfield in Sydney, smiled quietly and sat down. She was ready to play.

1

CAWARRA

The village of East Gresford, tucked away in the fertile lower Hunter Valley of New South Wales, seems a strange place to begin a story about fame and wealth.

Today its main street, framed by ghost gums and lined with neat lawns and timber-framed houses, wanders up and over a crest, past a small supermarket at the top of the hill, then a cafe, pub and butcher’s shop as the road bends left and down into the valley beyond. A church and cemetery with a few dozen worn headstones of long-dead pioneers marks the southern border.

That’s it. Don’t blink. Population, a few hundred.

Its beauty lies in its tranquillity: nestled into, or perched on the side of, an escarpment, depending on your perspective. Pollution-free skies grant clear views across soft yellow plains to purple hillsides in the distance, disturbed only by the chorus of warbling magpies and the haunting cooee of the common koel.

The pub, Beatty’s, and the church, St Anne’s, are the only buildings still standing from the nineteenth century when East Gresford and its nearby twin, Gresford, were thriving hamlets built by Europeans who came and transformed the traditional lands of the Worimi, Gringai and Biripi people.

The three clans had each occupied their own sections of the then heavily wooded valleys and hills around a surging river they knew as Kummi Kummi. The Gringai roamed the southern valleys, the plains to the west were regarded as Worimi country and the Biripi held the country to the north.

Their peaceful existence had been shattered in the 1820s when men came bearing land grants written and stamped by European bureaucrats who had unilaterally claimed ownership of the land. All because James Cook had planted a British flag in the sands of Botany Bay.

It had taken the best part of four decades for the white men to make their way inland from Sydney Cove, but once they arrived the impact was unyielding and permanent. The settlers cut and cleared, then fenced and planted, carved their roads and built their timber and stone homes with iron roofs.

The crops grew quickly and were bountiful in the silty loam soil; a strange mix of tobacco, citrus fruit, turnips, wheat and corn was trundled by wagon down to the town of Paterson, where it was loaded onto river steamboats bound for Newcastle and beyond to Sydney.

Settlements turned into villages and then towns, mostly with names from the old country chosen by the first to arrive. Gresford and East Gresford, linked by a one-kilometre track, were among them, named after the Welsh town where the area’s first landowners had lived. First there were rough homes, then shops and churches, schools, hotels, town halls and court houses to hold the community to account. It was, according to a letter to the editor in the Sydney Morning Herald, ‘an orderly, sober, well-conducted community’.

In 1841, a young man named Henry John Lindeman came to town to open a medical practice. East Gresford was beginning to flourish, with a new Catholic church being built and consecrated by the then Bishop of Australia, John Bede Polding—‘a measure of importance to the populous neighbourhood’, the local Maitland newspaper noted.

Henry was a doctor, as was his father before him. He had graduated from St Bartholomew’s Hospital and the Royal College of Surgeons in London and set up a practice in Southampton but, despite its prestige and security, the profession appeared to be a means to an end—a way to please his father perhaps—rather than his desired path in life.

Henry was a man with a wanderlust, having already travelled through France, Germany, India and China before deciding that England offered few prospects compared to the excitement of beginning a new life on the other side of the world. In February 1840 he married Eliza Bramhall, the eighteen-year-old ward of a local businessman, and a month later he and his new wife boarded the barque Theresa, where he had signed on as ship’s surgeon to pay for their passage as they sailed for Australia.

Either Sydney was a disappointment or, more likely, Henry was looking for something more than simply transplanting his medical practice from one side of the world to the other, because the couple did not stay long in the main colony, then a bustling town of 35,000 people. Opportunities lay inland.

Within a year of arriving in East Gresford, Henry’s purpose had become clear. Not only had he established his surgery but he had also bought six parcels of land outside the town, on the banks of the Paterson River. He called his 800-acre property ‘Cawarra’, an Anglicised version of the Aboriginal word describing running water.

He and Eliza also now had a daughter, Harriet, who would be the first of ten children. Henry built a slab cottage on the land and set about experimenting with crops, including tobacco and sugar, and running cattle. Then, inspired by his travels through Europe and a belief that the soil and climate here could produce table wine of quality, he decided to create a vineyard.

Wine had been produced in the colonies since vine cuttings were brought out by Governor Arthur Phillip on the First Fleet in 1788, but with mixed success. John Macarthur, the pioneer of the wool industry, was the first to establish a commercial winery and Gregory Blaxland, known mostly for being a member of the expedition, with William Wentworth and William Lawson, who crossed the Blue Mountains, was the first to export wine. Although arriving two decades later, Henry Lindeman would help bring a new, quality phase to the industry; he intended to allow his wine to mature and improve before sale.

His initial efforts were dismissed as vinegary but by 1850 Lindeman was able to present two samples—a red hermitage, ‘sound, of good flavour’, and a white hermitage, ‘delicate of pleasant flavour’—to the local vineyard association. As the Sydney Morning Herald reported: ‘In answer to inquiries, Dr Lindeman said the vines were young, the present samples being made from the first year’s produce.’

In another report he talked of growing vines in a mixture of river soil and vegetable mould, and fermenting the wine in open vats before it was casked. The results were promising but Henry wanted to let it mature, so he imported oak barrels from France in which to let it rest. In September 1851, as he prepared to bottle 4000 gallons, an arsonist burned down his winemaking building and destroyed the cellar he’d built beneath and its contents. Despite a reward, the identity of the ‘ruffian’ was never discovered. Just as he was about to produce his first full vintage, Henry Lindeman had been all but wiped out.

When his fifth child, Sidney Alfred, was born two weeks after the arsonist’s torch, Henry had little choice than to return to his medical practice and begin rebuilding his fortune, although there was another, more tantalising lure. Gold had just been discovered near the New South Wales town of Orange, followed soon after at Ballarat, Bendigo and Castlemaine in Victoria. The Australian goldrush had begun and the madness would spread like fire.

According to family lore, Henry packed his bags and headed to Victoria, hoping to cash in on the hysteria and population explosion, both as a medic but also try to strike it rich. Two years later, so the story goes, he headed home with his pockets full of gold, ready to restore and rebuild the vineyard.

Among the family tales is the story of the night Henry became lost in the bush on the way home, only to find wandering cattle bearing the Lindeman brand that led him back to Cawarra.

More often than not, family dynasties are created by forebears with vision and determination, whose struggles and passions, combined with a measure of luck, are instrumental in the family’s success. But in the retelling, sometimes fact and fiction become merged, and details are mangled or innocently embellished in the enthusiasm of the tale.

Such was the case with Henry Lindeman. Delightful as the family story is, these events have been romanticised. Author Dr Philip Norrie, in his 1993 book on the Lindeman family history, found no evidence of Henry holding a miner’s licence or being at any of the Victorian diggings. It is also unlikely, Dr Norrie concluded, that he spent so long away from home, given his wife fell pregnant again in 1853. Instead, Henry sold two hundred cattle—‘first-rate cows, bullocks, heifers and steers’, according to newspaper advertisements, to raise the funds he needed to rebuild the cellar.

There is, however, evidence that he did do some prospecting, and was successful—not in Victoria but around the town of Mudgee, about 250 kilometres to the west of East Gresford. In its issue of 10 November 1852, the Maitland Mercury and Hunter Valley General Advertiser published a report of activity in what it called the western goldfields, including activity around Louisa Creek, a tributary of the Meroo River near Mudgee where thousands of hopeful prospectors had flocked after the discovery of two large nuggets.

Among them was Henry Lindeman, who bought two claims around a nearby waterhole. In October, he struck it lucky, according to a report in the Empire newspaper on 6 November:

A waterhole was drained here by Dr Lindeman with some success. In three weeks, he took eighty ounces of gold, among which there were two nuggets weighing twenty and fifteen ounces respectively. The other day he sold one part of the claim for £15 and the other for one fourth of the proceeds. There will be very few persons at this creek in a short time, unless the weather becomes settled, so as to allow the bed being thoroughly worked. The country in the immediate vicinity is, however, almost untouched, and so far from there being any reason to think that it is not rich in deposits of the precious metal, there is every reason to believe the contrary.

The price for gold at the time was £3 per ounce, which meant that Henry had made around £240 and then sold his claim, presumably to head back to East Gresford. In relative income terms, it meant he was taking home around $300,000.

Lillian, the youngest of the Lindeman children, recalled her mother saying that they had been ruined financially by the fire and her father had agreed to go into a gold mine near Mudgee to work as a doctor because there had been so many accidents. ‘After he had made a good deal of money he started the wine, fixed up the cellars and began all over again.’

So, the story, in essence at least, was true. Perhaps even the wandering cattle.

Whatever his means, Henry Lindeman was determined to succeed. The vines were still intact and, after rebuilding his cellar, this time in stone, he started the maturing process again. By 1854 the business was back on track and his first vintages were receiving widespread praise around the colony. He had also built a new two-storey home and welcomed his sixth child, Charles Frederick, into the world.

In 1858, Lindeman’s exported its first wine and by the 1860s the company was winning medals in London and Paris. Henry bought smaller vineyards near the town of Corowa on the Murray River and at Rutherglen, across the border in Victoria, where he diversified into heavy sweet wines such as port, muscat and sherry, and also distilled brandy.

His main interest, however, was in producing light wines suitable for drinking with a meal. In 1860, one journalist wrote of a ‘pale, clear and light wine possessing bouquet and a very delicate flavour’, concluding: ‘It must be Dr Lindeman’s wine.’

By 1870 Henry had moved his winemaking operation to Sydney, establishing new headquarters there, including a winery, cellars and a bottling complex at a building in Pitt Street. He became a loud voice in the political battle between winemakers and the more powerful lobby of rum producers. When the NSW Parliament passed laws unfavourable to wine, he thundered: ‘It clearly shows that the rum bottle interest is all-paramount, and the majority of the House are its abject slaves.’

By the time he died in 1881, Henry Lindeman had helped put Australia on the world stage in terms of wine and was regarded as one of the industry’s pioneers. He was a wealthy man, yet had always remained living in the house he built at Cawarra. His grave is among those in the cemetery at St Anne’s, the tiny church at the southern border of East Gresford, where his headstone notes only that he had lived for sixty-nine years and eight months.

2

AN INDEPENDENT SPIRIT

Henry Lindeman introduced his sons to the business several years before his death, although only three would remain involved with its operations. Arthur, the eldest son, would be the winemaker and Herbert, the youngest boy, was trained as the taster, his father insisting that the human palate was the only true test of a wine. Overall management for the business would fall to Charles, the middle son born in 1854 as his father rebuilt the winery business after the cellar fire.

The brothers traded under the name H.J. Lindeman and Company after their father’s death and continued the company’s success internationally with medals at Paris and Bordeaux, among other exhibitions. They also became a dominant force in domestic competitions as their father’s dreams of a flourishing wine industry came to pass and the state’s infatuation with rum faded.

If Henry had been the visionary, then Charles—tall and square-jawed, with piercing eyes and a mop of rust-coloured hair—was the champion of Lindeman’s quality, as the company became the country’s biggest producer and its most successful exporter. Faced with accusations by jealous competitors that they used additives to produce extra flavour, Charles lobbied the NSW Premier Sir Henry Parkes, offering to donate £1000 to charity if government inspectors could find ‘any colouring matter, added spirit or flavouring, in fact anything that is not absolutely grape juice’. None was found.

What had begun as an experiment by their father had become an empire as the operation was moved from Pitt Street to the Queen Victoria Building, in George Street, where the company transformed the basement into a giant cellar. The plaudits flowed, such as from the Sydney Mail in August 1893: ‘Science and skill have been brought to bear on the vineyard’s yield . . . and the business grew and prospered and is now in full bloom, promising to go on like some of the old wine houses of France, the reputation of which is ever before the world. Since 1881 Mr Charles F. Lindeman has taken charge of the business which, under his care, has increased to very large proportions. Prizes innumerable have been won in France and Australia and, as stated in one of the papers, Mr Burgoyne, the British wine merchant, before leaving Australia recently, spoke of Lindeman wines as the best in Australia.’

While the vineyard at East Gresford continued to expand and others were acquired, the heart of the operation was now Sydney, where Charles would set up a home with his wife, Florence. Following the trend of large families, they would have seven children.

First would come four sons, neatly spaced two years apart—Frederick the eldest in 1884, followed by Grant (1886), Rupert (1888) and Roy in 1890. At this time Charles was busily expanding his business empire by buying into hotels which, of course, would carry Lindeman wines in their cellars.

On 8 January 1892, as the new house was being completed, Florence gave birth to their fifth child—a daughter they named Enid Maud.

Literature would in time play a frequent and significant role in the life of Enid Lindeman. This was often because of the people with whom she surrounded herself, those she admired and whose advice she sought.

As a child she had two favourite books, both written by Australian women. The children’s classic Dot and the Kangaroo, the story of a young girl who becomes lost in the bush and is befriended by a kangaroo that gives her magic berries and guides her home to safety, was published in 1899 when Enid was aged seven, sparking the imagination of a child who already adored her own pet kangaroo, which followed her around like a dog.

Drawing on the lost child trope and fantasy of works like Alice in Wonderland and Hansel and Gretel, Dot and the Kangaroo was an early story of conservation; its author, Ethel Pedley, entreated her young readers to appreciate and respect the fragile beauty of the Australian bush and its animals.

It was a lesson that would stay with Enid. Her love of animals would continue through her life as would her fascination with the natural landscape of her homeland, and she spent as much time exploring the wilds of northern and central Australia as the ballrooms and racetracks of Sydney and Melbourne.

Her teenage years were influenced by another novel, Seven Little Australians, which seemed to mirror so many aspects of her own life, from the matching number of children in the fictional Woolcot family to their home, Misrule, in Parramatta not far from the Lindeman home, Bramhall, in Strathfield, and even a country property where they spent holidays, as the Lindemans did at Cawarra.

Enid could identify with the adventures of the mischiefmaking Judy and her older brother, Pip. The author, Ethel Turner, lauded the ‘lurking sparkle of joyousness and rebellion’ that set Australian children apart from their English and American counterparts who were, in Turner’s mind, boring paragons of virtue.

This conclusion matched many of Enid’s own experiences of a childhood in which she was closer in age to her four older brothers than to the two sisters who would come after her—Nita, five years younger, and Marjorie, a full decade behind. Circumstances forced her to compete against the boys and hold her own by learning to ride, hunt, shoot and fish as adeptly as they did—skills that helped create an independent spirit that drove much of her adult decision-making in a man’s world.

The seven Lindeman children grew up in the southwest suburb of Strathfield, an area initially created as a series of agricultural holdings, roughly at the halfway point between the main colony and Parramatta, but eventually subdivided to provide housing as Sydney’s population continued to grow and push outwards.

It seems a strange area for a wealthy man like Charles Lindeman to build a home, which he named Bramhall after his mother’s family, 15 kilometres outside the city centre where he travelled almost every day to oversee the cellar at the Queen Victoria Building, when he could easily have bought in one of the inner suburbs that stretched along the southern shore of Sydney Harbour.

Perhaps that was his chief reason. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Sydney’s population had reached almost 500,000, crowding its inner suburbs, whereas Strathfield had space—freedom as Enid would describe it to her own children, reflecting on a childhood of open spaces, picnics on secluded beaches to the booming sound of crashing surf and the camaraderie of harvest time among the vineyards of Cawarra.

These were powerful influences, as her eldest son, Rory, would later reflect about his mother in his 1950 book My Travel’s History: ‘A beautiful woman, and much spoiled by those who loved her, she would sometimes come to my nursery in a shimmer of beads, her hair closely cropped to her head. If she had time before going down to dinner, she would sit on the end of my bed and tell me stories, or read me snatches out of the books she had enjoyed as a child. I retain vivid memories of stories she told me of her tomboy youth spent with her brothers and the fun they had while the grapes were being gathered.’

At almost 6 feet tall, with the jawline of her father and the bluegreen eyes of her mother, Enid always attracted attention, even as a teenager attending Ascham School, then in Darling Point, Sydney, for girls of well-to-do families, where she won prizes for music, painting and elocution and appeared in school plays, as noted by the school magazine Charivari, which detailed the school’s day-to-day affairs.

Enid was best known for her sporting prowess. Rangy and athletic, she quickly won the nickname Diana when she arrived at the school aged fifteen, a reference to the Roman goddess of the hunt and indicative of her influence on the sporting field. The students were encouraged by Principal Herbert J. Carter, who believed in the benefits of sports for young ladies, and was supported by his wife, Antoinette, whose photographic albums make up a large proportion of the school’s extensive archives.

One photo of the school’s Basket-Ball side (an early field version of netball) shows Enid towering, giraffe-like, over classmates. She also played tennis for the school as well as the ball game rounders, helping to coach other students.

But it was the introduction to games such as croquet and golf and learning to ride a horse that would become the more important social skills in her adult life, as would a talent for art, sewing fine tapestries, watercolour painting and even creating murals that would adorn walls of her homes.

Enid was a weekday boarder, living from Monday to Friday in a grand colonial house, ‘Mount Adelaide’, that stood on Darling Point Road with views across the deep waters of Sydney Harbour to the distant shoreline of Mosman, long before the Opera House and Harbour Bridge were conceived. It was a vista she would remember decades later when she bought a home on the other side of the world that commanded an equally imposing vista.

Enid attended the Ascham School for only two years, in 1907 and 1908, and left just before her seventeenth birthday with no plans to attend university—a seemingly aimless education that, according to the school’s archivist Marguerite Gillezeau, was all too common for young women of well-to-do families: ‘I would say Enid came to Ascham specifically to complete her last two years of school. She was in sixth form, the top class, although I doubt she matriculated. It was very rare in that era for girls to matriculate from Ascham, not because it wasn’t a good school academically, but because the majority of the parents weren’t on board with the idea of their daughters going to university. The staff were constantly trying to promote the idea of tertiary education, but it wasn’t until after World War I that it was taken more seriously by the parents when the social reality of the post-war era became apparent.’

Instead, Enid Lindeman left school with one goal in life—to marry well. It was not necessarily a shortcoming on her part, a lack of imagination or laziness, but merely the expectation for women in the first years of the twentieth century. Tradition stated that brothers divided the spoils of family assets—the eldest usually taking the lion’s share—while their sisters cleared the path and avoided becoming financial burdens by finding husbands. Love was a secondary consideration to the practicalities of lineage.

That was certainly the case in the Lindeman family. Henry Lindeman’s five sons—Arthur, Sidney, Charles, Herbert and Henry—took control of the fortune and business while sisters Harriet, Mary and Matilda dutifully married a doctor, a politician and a lawyer. Louisa and Lillian went even further, wedding the sons of rival vineyard owners, which not only fulfilled their obligations but built new financial bridges for the Lindeman empire.

The rare exception to this rule was if a woman could not find a husband; in that case she would remain in the protective bosom of the family. Not that marriage necessarily provided financial security for women, given what the Weekly Chronicle in South Australia described in 1894 as ‘the practically unlimited powers’ a man had to organise and control family finances.

But the beautiful Enid Lindeman was never going to be a spinster.

3

LETTER FROM AMERICA

In the autumn of 1912, a wealthy middle-aged American businessman named Roderick Cameron arrived in Sydney to oversee the expansion of his shipping company. It was his second trip to Australia, and the month-long journey from his home in New York—first across the continent by train to San Francisco and then by steamship across the Pacific—was reason enough to stay for several months before returning.

Cameron was named after his father, the New York shipping magnate Sir Roderick Cameron, who had nurtured the business from its beginnings in 1852 when, as a lowly clerk in a Canadian export company, he had seen an opportunity, chartered a steamship and had begun taking passengers and supplies from North America to Australia to join the goldrush that was rapidly expanding across the continent.

The venture was an immediate success as thousands of hopeful men made the journey on what he called the Pioneer Line. The business continued to grow in the years after the goldrush faded, as Cameron expanded into transporting farm machinery, as well as general produce, to Australia, New Zealand and later to Europe.

By the 1880s Sir Roderick had shifted to New York and became one of that city’s most prominent businessmen. He had also established a commercial presence in Sydney, where he mingled with its political elite, including the Premier Sir Henry Parkes, who would visit the US to cement economic ties. He had got to know business leaders such as Charles Lindeman, with whom he worked on several trade delegations, including representing New South Wales in the World’s Trade Fair held in Philadelphia in 1876.

When Sir Roderick died in 1900 at the age of seventy-five, his second son and namesake took over the business, and continued to foster the relationships in Australia. Roderick Jnr had visited in 1908; when he returned to cast his eye over the operation in 1912, he based himself in an office in Pitt Street.

He was a serious and studious man with soft features and anxious eyes, who in photographs grimaced rather than smiled and looked older than his forty-five years. He was also single, highly unusual for a man of his wealth, and understood how important it was to have sons to whom he could pass on the family name and fortune.

There had previously been some talk of a marriage to the daughter of a society family but he had pulled out of the engagement. Now it seemed he had put aside any notions of a wife and family and was content to concentrate on the business empire he managed on behalf of his siblings.

But that would all change a few months after he arrived in Sydney, when Roderick was introduced to twenty-year-old Enid Lindeman at a charity ball held at the Town Hall. He was immediately smitten by the tall, graceful woman and decided that it was time to roll the marriage dice. Enid’s feelings about a man old enough to be her father were never recorded, although, given the speed of their engagement it seems likely that she was attracted by his quiet smile and sureness as an older, successful man. After all, men around the ages of her brothers had always been regarded as competition rather than romantic partners.

Enid’s mother was against the union at first, concerned at the significant age difference, but when the businessman made it plain that he was prepared to stay in Sydney and win her approval, Florence Lindeman eventually changed her mind. She gave the couple her blessing when her eldest daughter turned twenty-one on 8 January 1913.

It was a time of change for women. The suffrage movement in Britain was at its loudest, forcing debate not only about political emancipation and equality for women but also about changing the marriage vows and, among other things, removing the expectation that wives had to ‘honour and obey’ their husbands.

But society would move slowly, stymied by antiquated attitudes and expectations: ‘A new danger has arisen on the horizon of woman,’ a December 1913 report in the Daily Telegraph warned about a study of female university students. ‘If she is clever and is educated she has less chance of being married than if she remains just a simple young person of attractive appearance and manners. In fact, the more educated she becomes, the less chance she seems to have of marriage.’

Enid Lindeman fell somewhere in between, having been home-schooled before her final two years of secondary education. Whether she had ambition or not was irrelevant and, despite their age difference, Roderick Cameron was a marital catch.

Their wedding on 12 February 1913 was described by The Bulletin as ‘a festive affair’. The morning ceremony at St Paul’s, Burwood, was conducted by her great uncle, the Rev Septimus Hungerford, before a reception for two hundred or so guests back at the family home.

The unplanned nature of the union was highlighted by the fact that no one from the Cameron family had made the long journey from New York. Instead, Roderick’s best man was a Sydney businessman named Colin Caird, whose only connection was through his business relations with Charles Lindeman and a shared Scottish heritage.

Yellow in all its subtle shades was the season’s fashionable colour and a description of the wedding party’s outfits dominated newspaper coverage, including The Bulletin, which noted a few days later that the bride was ‘gowned in cream duchess satin with a tulle veil and small coronet of orange blossom’. Her six bridesmaids wore lemon chiffon and, after the ceremony, Enid changed into a grey crêpe de Chine coat and skirt and a black velvet hat, set with ostrich plumes, before the couple left to drive down to Bowral for the honeymoon.

The media coverage was very different back in the United States where the Washington Post, among others, made subtle hints about the age difference and haste of the ceremony.

Friends of Mr Roderick MacLeod Cameron were greatly interested as well as surprised to learn that he and the daughter of a prominent merchant of Sydney, Australia, were married yesterday in that distant city. Only members of his family and business associates were informed that his long stay in Australia was to culminate in his marriage. The bride of Mr Cameron is Miss Enid Lindeman, whose father went to Australia many years ago and established a large export trade. The transportation business of Mr Cameron, and expansion of that established by his father, the late Sir Roderick Cameron, brought him into commercial relations with Mr Lindeman long before he went to Australia, about a year ago, when he first met Miss Lindeman.

16 May 1913

My darling mother,

We seem to have done nothing but travel the last week. The last day I wrote to you was on the 7th and we have been on the go ever since. I’m just longing to hear from you or Dad, it seems such ages since I last heard from anyone and we would not get any letters till about the 1st June as we don’t get to New York till then.

The newlyweds had sailed from Sydney in early April aboard the steamship Ventura, among the two hundred and fifty passengers who settled in for the three-week voyage across the Pacific to San Francisco via Samoa and Honolulu. After arrival, it would normally take another five days to make the journey across the vast continent by train to New York, but Roderick Cameron was in no rush.

Instead, he wanted to show his bride the wonders of her new home and set off inland by train toward the Yosemite National Park, arriving at the hamlet of El Portal. Here, they stepped back in time and onto a stagecoach that would take them through treacherous, unsealed roads to the centre of America’s wilderness gem.

Enid was spellbound by the scenery during the four-hour drive, leaning out of the coach as far as she dared on a trail that clung precariously to the snow-capped mountainsides above the Merced River that boiled and bubbled like a raging sea while alpine forests stretched, uninterrupted by humans, as far as the eye could see. That evening, she sat on the verandah of the Sentinel Hotel, beneath the towering granite peak after which it was named, and watched in wonder the Yosemite Falls in the distance, the thin line of water plunging hundreds of metres into a seemingly bottomless chasm: ‘Try and imagine that height . . .’ she wrote in admiration.

It was a world far from her usual city life of fine clothes and social parades, and yet strangely comforting given the Lindeman family’s connection to the land. But these were not the gentle slopes of the Hunter Valley, as Enid discovered the next day when she eagerly volunteered to hike several miles of trails and climb the side of a cliff. She wanted to get a closer look at one of the nearby falls, the Vernal, and sit by the side of the Emerald Pool, where the waters gathered before being swept over the edge and crashing like thunder on the boulders below.

And it seemed that, despite Florence Lindeman’s initial concerns, Rory, as Enid now called Roderick, was an attentive husband. She wrote: ‘Rory was very anxious for me to see them and was afraid it was too far to walk, so rather than I should miss them he got a large rope and tied it around my waist then around him. It is a two mile trail up the side of a mountain. I quite enjoyed the walk and Rory didn’t seem to be any the worse for it.’

The journey continued two days later. The roads were even rougher as the stagecoach took them deeper into the park, where ancient sequoia trees grew in giant stands and deer roamed without fear of humans. Guns were banned yearround and the park was about to be handed to a civilian team of rangers to manage the delicate balance between conservation and tourism. Enid was thrilled at the sanctuary as she fed squirrels by hand.

The journey east continued, first by stagecoach and then by an overnight train into Arizona, where Enid sat down to write a letter after watching the sun set over the Grand Canyon. Despite its natural glories, the trip was beginning to wear her down physically.

It made me as ill as if I was sea sick, so rough I wonder I have any inside left. That drive took us seven hours and we changed horses nine times. All that jolting was hell but then we had to catch the train . . . and spent all that night and all the next day and the next night in the train. Ah! Ye Gods, I can’t tell how sick I was. Poor old Rory did all he could in the way of making me comfortable. He got a drawing room car that has twin beds and a couch, and all to ourselves so I could lie down all day as well. We arrived here at the Grand Canyon at 8.30 so I went straight to bed and didn’t get up till lunch time, then in the afternoon I wrote the first part of this letter to you and at 6.30 we drove out nine miles to see the sunset on the Grand Canyon. It’s quite the most wonderful sight in all the world. I’ll enclose a post card and let you have an idea what it’s like. The colours are marvellous, and they seem to change every hour or so.

Her mood had improved the next day when they visited a nearby Native American reservation and watched women making baskets and weaving rugs. But it wasn’t the craft work that grabbed Enid’s attention: ‘One woman had the sweetest baby you ever saw. Only nine weeks old and slipped into a basket alongside her. It looked as if it couldn’t move a finger and yet it was as good as gold. I sat there for quite a while nursing it and the mother was pleased as punch, laughing and talking away in her own tongue.’

It was also clear that whatever Enid and Roderick’s initial reasons for marriage, their relationship had blossomed. The couple were very much in love, their evenings spent together playing cards as Rory taught his wife the basics of gambling: ‘I’ve won £4 from Rory—$20,’ she wrote proudly. ‘He will be starting to feel sorry he taught me the game.’

She was also becoming playful with her husband: ‘This climate is the devil for one’s skin. Mine feels like parchment and any bit of metal you touch gives you an electric shock. If I think Rory looks too peaceful, I run my feet along the carpet and then touch the end of his nose with my fingers and get a spark. It makes him jump out of his seat.’

In all the news and travelogue, there was one thing Enid was not telling her mother. The travel illness was not the result of a bumpy ride and Rory had good reason to be concerned about her ability and safety to climb mountain trails. The clue lay in her clucky delight in nursing the Native American woman’s baby: Enid was three months pregnant.

4

A BIRTH AND A DEATH

One of most prestigious residential addresses in New York at the turn of the twentieth century was Murray Hill, a neighbourhood bounded to the north and south by East 42nd and East 34th streets, and to the west and east from Madison Avenue through to the East River.

Future president Franklin Roosevelt lived on 36th Street, as did the influential financier John Pierpont Morgan, who built a library next to his home. The fabulously wealthy Vanderbilt family kept a townhouse nearby, surrounded by many of the merchants and industrialists who had made their fortunes during the so-called Gilded Age of the nineteenth century.

Sir Roderick and Anne Cameron had owned a large house at the southernmost tip of Murray Hill, the corner of East 34th Street and Madison Avenue, where they raised their seven children—five daughters and two sons. By all accounts, Sir Roderick was a fearsome man, at times overbearing and particularly proud of being the only man in New York with an English title, bestowed on him by his native Canadian government for his contribution to business.

He also owned a large property on Staten Island, a ferry ride past the Statue of Liberty to the south of the city, where he established Clifton Berley, one of the country’s best-known horse studs. He was considered one of the fathers of US thoroughbred racing: ‘I have clung tenaciously to my farm and shall hold it for my children,’ he once declared, confident the island would one day become a city. ‘What grounds have I for such hope? Well simply this: We are within an hour of Wall Street, the great civilizer and founder of cities.’

A century later Staten Island is one of the city’s five boroughs, the grandeur of Clifton Berley swallowed up by the suburbia that Roderick Cameron accurately predicted. A lake that was once on his property and the local recreation club both bear his name.

But for all their wealth and prominence, the Cameron family would not be immune from tragedy. Anne Cameron had died of fever in 1879, three days after delivering their seventh child, a girl named Isabelle. A year later, nineteen-year-old daughter Alice would succumb to tuberculosis and in 1906, Isabelle, who had established a career as an artist and writer, would also die suddenly after being mauled by a dog.

Roderick Jnr, the youngest son and middle child, had taken over the management of the empire when his father died in 1900. His brother Duncan, two years older, was the natural heir but had been disgraced earlier when he became embroiled in a divorce case in which he was accused of taking money from his wife and being violent in a two-year marriage that ended with his wife ‘kidnapping’ their daughter.

It had been a messy affair, publicly as well as privately, and was only compounded when Duncan, penniless after wasting an inheritance from his mother, fled to London in the late 1880s, where he ran up debts to a jeweller for expensive gifts he bought for several girls, including ‘an actress’. Sir Roderick had travelled to London to front court on behalf of his son, only to leave fuming and embarrassed by events.

And so the mantle of successor had fallen to Roderick Jnr, steadfast, principled and anointed by his surviving sisters who, unusually, had been given equal shares in the multimilliondollar inheritance left by their father.

For all his quiet ways, Roderick Jnr would prove a steely businessman, pursuing not only the family’s shipping interests but taking a lead in New York life—as a member of the exclusive Knickerbocker and Union clubs, a property developer and a proponent of change. His energy was perhaps best illustrated by what another man in his position might have considered a minor matter and not worth his time—his decision to fight and overturn what he believed to be an unfair tax on owners of pet dogs. He won.

There was precious little room for sentiment in his life. In 1910, he and his older sister, Margaret, decided to demolish the family home in Madison Avenue as well as the house next door. They did not want to rebuild a grander home to show off their wealth, but to construct a sixteen-storey office building.

It proved a canny, if controversial development. The commercial centre of New York, a city hemmed in by water on three sides, was creeping ever northwards and the Cameron Building, as it would be named, would be among the first to be built in an established residential area, much to the annoyance of wealthy bankers and industrialists, whose mansions and brownstone townhouses lined the genteel cobblestone streets.

But Cameron stood firm, even refusing an offer of $600,000, triple what they had paid to purchase the land, to abandon the project and then winning a lawsuit brought by some of their wealthy neighbours who argued that, if allowed, the project would set a dangerous precedent.

The neighbours were right. Roderick Cameron’s audacious victory would spark a commercial property boom that would alter the face of the city. The Cameron Building still stands more than a century later, no longer on the edge of the city proper but in Midtown, the heart of the city and home to many of the city’s iconic buildings, including the Empire State Building, just a few blocks to the east, and the Macy’s flagship Herald Square department store, which inspired the movie Miracle on 34th Street.

Enid Lindeman was born in a colonial city built at the edge of the world and raised on its suburban fringes. She had lived in a neighbourhood bound by picket fences, large yards and unsealed roads, a place of space and freedom and silence interrupted occasionally by the lonely whistle of a train pulling into Burwood Station. The city centre, 15 kilometres east, was a place of mostly four-storey buildings where horses and carts and lumbering trams still dominated the streetscape; its glorious natural harbour was tucked away at the northern end—an entry and exit to the world beyond.