8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

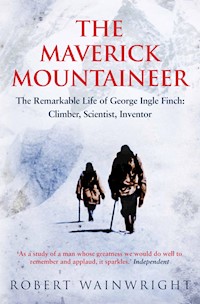

WINNER OF THE TIMES 2017 BIOGRAPHY OF THE YEAR PRIZE SHORTLISTED FOR THE 2016 BOARDMAN TASKER PRIZE FOR MOUNTAIN LITERATURE 'One of the two best Alpinists of his time - Mallory was the other.' The Times In the spring of 1901 a teenager stood on top of a hill, gazed out in wonderment at the Australian landscape and decided he wanted to be a mountaineer. Two decades later, the same man stood in a blizzard beneath the summit of Mount Everest, within sight of his goal to be the first to stand on the roof of the world. George Finch was at the highest point ever reached by a human being and only his decision to save the life of his stricken companion stopped him from reaching the summit. George Finch was a rebel of the first order, a man who dared to challenge the British establishment who disliked his independence, background, long hair and lack of an Oxbridge education. Despite this, he not only became one of the world's greatest alpinists, earning the grudging respect of his rival George Mallory, but pioneered the use of the artificial oxygen that enabled Everest to finally be conquered thirty years after his own attempt. A renowned scientist, a World War I hero and a Fellow of the Royal Society, involved in the development of some of the twentieth century's most important inventions, his skills helped save London from burning to the ground during the Blitz. Finch's public accomplishments, however, were shadowed by his complicated private life and his fraught relationship with his son, the actor Peter Finch. Acclaimed biographer Robert Wainwright restores George Finch to his rightful place in history with this remarkable tribute to one of the twentieth century's most eccentric anti-heroes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Allen & Unwin

Originally published in Australia in 2015 by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Pty Limited

Copyright © Robert Wainwright, 2015

The moral right of Robert Wainwright to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Allen & Unwin c/o Atlantic Books Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ Phone: 020 7269 1610 Fax: 020 7430 0916 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 76011 349 0 Ebook ISBN 978 1 92526 843 0

Typeset by Kirby Jones in Great Britain

Cover images courtesy Mrs A. Scott Russell

To my wonderful sons, Stevie and Seamus

contents

Part I

1. To See the World

2. A Boy from Down Under

3. A New Hemisphere

4. Whymper’s Path

5. A Zest for Mountains

6. Everest Dreaming

7. King of His Domain

8. The Tyro Companion

Part II

9. An Alchemy of Air

10. The Upstart

11. A Jilted Hero

12. Pleasure and Pain

13. The Last Frontier

14. The Lost Boy

15. ‘You’ve Sent Me to Heaven’

16. ‘Dear Miss Johnston’

17. The Threshold of Endeavour

Part III

18. Prospects of Success

19. The Politics of Oxygen

20. ‘When George Finch Starts to Gas’

21. The Road to Kampa Dzong

22. Goddess Mother of the World

23. The Foot of Everest

24. The Right Spirit

25. A Bladder and a T-Tube

26. The Ceiling of the World

27. ‘My Utter Best. If Only …’

PART IV

28. The Unlikeliest of Heroes

29. The Bastardy of Arthur Hinks

30. A Dream is Dashed

31. The Tragedy of George Mallory

32. A New Legacy

33. The Beilby Layer

34. F Division and the J-Bomb

35. ‘Whose Son Am I?’

36. Conquered

37. Recognition at Last

Epilogue

Acknowledgments and Notes on Sources

PART I

1. TO SEE THE WORLD

George urged his pony up the steep slope. He could feel the animal’s laboured breath beneath him, its flanks glistening with sweat as they pushed higher and higher, through the stands of crouching snow gums and silver-leafed candle barks that clung to the side of the long-extinct volcano.

The boy would remember the morning that would come to define his life as dewy. It was early October in 1901, one calendar month into spring, and the Australian bush around the inland New South Wales town of Orange – higher, wetter and cooler than the land to the west or the east – was still thawing from the winter, the mornings dark and frosty.

He had been up for hours, riding out from the family property to hunt for wallaby before the sun crested the surrounding ranges to melt the overnight frost and wash the countryside in pale gold. He might have woken his younger brother, Max, but had thought better of it, preferring to be alone in the waking bush with the utter sense of freedom that it brought.

Tall, lean and physically mature beyond his thirteen years, George had skirted the sleeping town and headed for Mount Canobolas, the highest inland point of the tablelands, a dozen or so miles to the south-west, where he was confident he would find the kangaroo-like marsupial feeding in mobs as the day warmed.

He and Max had hunted in the lower reaches of Canobolas many times before, but had never been interested in venturing up the towering rise, let alone pondering the origins of its name, a rather loose attempt at replicating the local Aboriginal word meaning a twin-headed beast.

They would come here to hunt, skinning and stretching the pelts of the animals they shot so they could be sold to dealers for fourpence each, and then using the money to buy fresh ammunition. But it wasn’t the financial reward that drew George, who once sewed his mother a blanket from the six wallaby hides of a successful hunt. The money was simply a means to an end for a boy from a well-off family who relished the challenge and strategy of the hunt itself.

On this day George had found the wallabies easily enough – a mob of them at a waterhole in the virgin bush. He had waited, patient and content in the silence, for an opportunity, but when it came the flash of his gun barrel in the morning sun had stirred the animals and they’d scattered into the trees. Instead of following and perhaps scaring them further, George had decided to get to higher ground so he could spy where they had settled and try again.

There had never been a reason to climb even the lower reaches of Canobolas, and its freshness was intoxicating. The air was cooler up there as the mountain continued to shed the remains of its white winter coat. Small patches of snow still weighed down the boughs of some trees, ready to fall, melt and pool in the rock gullies where it would feed the flush of an Australian spring already evident in tiny flowers of kunzea, fringe myrtle and mirbelia that would soon explode into a blaze of white, yellow, red and violet.

It was mid morning when George reached a point high enough to be able to spot the wallabies again but he did not stop, instead choosing to keep going, the hunt all but forgotten as he sought the peak. One challenge had been replaced by another.

When it got too steep he searched for alternative routes where his pony, sturdy and sure-footed, could tread. At last he broke free of the dense foliage and reached a vast rocky outcrop that tapered into a stepped chimney to the summit, a series of upright rectangular blocks of stone that might have been placed there by a giant hand. His mount could go no further but, eager to continue, George dismounted and scrambled to the top in a few minutes, barely raising a sweat – then stood transfixed at the sight before him.

He hadn’t stopped to consider what he might see from the summit or how his perspective of the world might change simply by viewing it from above. His eyes roamed across the scene in front of him, unable to pause even for a moment, such was the surreal nature of the view. Olive-green fingers of bushland reached out from Canobolas as if trying to claw back the plains of yellowed farmland that spread toward the Great Dividing Range, its rolling curves layered in hues of brown, blue and purple as they stretched to the horizon.

When he lowered his eyes and squinted into the still-rising sun, George could make out the glinting galvanised-iron rooftops and whitewashed walls of the houses of Orange, positioned in neat rows beside wide dirt roads crafted like ruled pencil lines, which led, ultimately, to the jewelled city of Sydney, 150 miles to the east. Years later he would recall the moment as clearly as if he was still standing there: ‘The picture was beautiful; precise and accurate as the work of a draughtsman’s pen, but fuller of meaning than any map. For the first time in my life the true significance of geography began to dawn upon me, and with the dawning was born a resolution that was to colour and widen my whole life.’

George remained atop Mount Canobolas for what seemed like hours, eventually tearing his eyes from the view and reluctantly climbing back down the stone steps to retrieve his pony. The boy would return home empty-handed several hours later but it mattered little, the spoils of a hunt replaced by a vision of his future: ‘I had made up my mind to see the world; to see it from above, from the tops of mountains whence I could get that wide and comprehensive view which is denied to those who observe things from their own plane.’

George Finch, a boy who until then had only seen his world from the height of a saddle, wanted to be a mountaineer.

2. A BOY FROM DOWN UNDER

Early in the summer of 1891, a few months after his son had turned three, Charles Edward Finch picked up the boy, dangled his legs over the side of a small wooden dinghy and plopped him into the calm, crystal waters of Sydney Harbour with the simple instruction, ‘Swim, George, swim.’

The boy would do as he was told, fighting his way back to the surface and furiously dog-paddling to the gunwale, where he was plucked to safety by those same strong hands. George Finch would tell the story many times over the years, always fondly, dismissing any outrage among the listeners by arguing that his father had acted not out of cruelty but love, believing that in order to survive and thrive his son had to learn early to take care of himself.

The legacy of self-reliance that Charles Finch wanted to pass on to his children was not surprising given his heritage. His father, a redcoat soldier named Charles Wray Finch, the son of a far from prosperous clergyman, had arrived in Sydney aboard the convict ship Hercules in 1830 after a harrowing five months at sea. Once in New South Wales he was quickly promoted to the rank of captain, although he was not interested in a military career, and when the opportunity arose he resigned his commission to take up an appointment as a police magistrate. It was the beginning of a social and economic climb that would eventually make him one of the most prominent men of the colony, and his prospects were boosted by his marriage to Elizabeth Wilson, eldest daughter of the colony’s powerful police magistrate, Henry Croasdaile Wilson.

The Finches soon quit Sydney and helped lead the push inland from the main colony, accepting Crown grants to develop the fertile agricultural and pasture land west of the Dividing Range. It was on a sheep station in the Wellington Valley that Finch called Nubrygyn Run (based on an Aboriginal phrase meaning the meeting of two creeks) that he not only made his fortune but, with Elizabeth, raised a family of nine children.

The station, running more than 12,000 sheep and 800 cattle, was a lush, blooming oasis in an otherwise harsh landscape, its homestead a sprawling stone building with seven bedrooms for family members and guests and large drawing and dining rooms for entertaining, leading onto a broad timber verandah with views across tended lawns to a creek that fed the paddocks. There were extensive vegetable gardens and an orchard with grapevines and over three hundred trees – peaches, cherries, apples, pears, plums, nectarines and apricots among them.

The gardener lived in a stone cottage, as did the station overseer, and there were separate quarters for household staff and the twenty-five farmhands, stockmen and shearers needed to run the operation. At the back of the house stood the stables and horse paddocks, to the side a massive brick woolshed with a 30-foot shearing floor and boasting the only hydraulic wool press in the district.

Charles Wray Finch would live at Nubrygyn for fifteen years before selling part of the property and securing a manager to run the large parcel of land that remained. He took his large family and fortune – ‘estates of several thousand acres in extent in the county of Wellington and house, cottages and town allotments at Parramatta’ – and settled back in Sydney where he was welcomed into business and political circles, becoming a founding member of the Australian Club, joining the committee of the Royal Agricultural Society and being elected to the New South Wales Parliament. He was the parliamentary sergeant-at-arms, keeping order in the House, when he died suddenly in May 1873.

Charles Edward was his third child and second-oldest son, brought into the world in the main bedroom of Nubrygyn in 1843 and spending the first dozen years of his life on the station, until he was sent off to the King’s School in Parramatta, making the journey on the back of a bullock wagon hauling wool bales to the city. Although he was ingrained with life on the land, the family’s move to Sydney in 1855 shifted his expectations from the hardy life of a farmer to a privileged city existence and career. He graduated from high school with good grades, but surprisingly chose to bypass a university education in favour of a position with the New South Wales public service as a draughtsman. With diligence, and aided by the standing of his father, Charles worked his way through the ranks to become a district surveyor.

In 1885 Charles Finch would return to the Wellington Valley when he was appointed chairman of the Land Board at Orange, presiding over disputes concerning the Crown Lands Act, the guiding document in the division of New South Wales’s vast tracts of arable land. In this role he would become more powerful than his father in many ways. He was a physically imposing man, tall and square-jawed, his neatly trimmed white beard contrasting with his dark, prominent eyebrows. His manner complemented his physical appearance: regarded as an uncompromising but fair man, he was a stickler for the rules and famous for once successfully defending a decision before the Privy Council in London, for which he earned the nickname ‘King’.

Charles had never quite lost touch with his farming background. As the oldest surviving son (his elder brother had died in a farming accident), he inherited Nubrygyn when his father died and assumed the role of gentleman farmer, adhering to the strictures of Victorian morality and fashion, and donning formal dress for dinner, even in the heat of an Australian summer. He had married in 1870, aged twenty-seven and well set in his career, 21-year-old Alice Sydney Wood, the only daughter of a prominent family in a ceremony presided over by the Lord Bishop of Sydney. The marriage was widely reported in colony newspapers, as was Alice’s sudden death just a year later, most probably in childbirth.

The loss of his young wife seemed to traumatise Charles because he remained widowed for the next sixteen years. He was finally married again in 1887, two years after moving back to Nubrygyn, this time to nineteen-year-old Laura Isobel Black, a woman twenty-five years his junior, who quickly bore him three children before he turned fifty.

George was the oldest, born on August 4, 1888, as Sydney celebrated the centenary of the First Fleet’s arrival, while the rest of the populace, scattered across the vast southern land, grappled with the notion of a unified nation rather than a collection of independent states. By the time George Finch climbed Mount Canobolas on his pony thirteen years later, the Federation of Australia had been created, sparking the beginnings of a national identity that would be tested and refined by a world war that would soon devastate the fledgling nation with the loss of more than 60,000 lives.

Learning to swim was not the only lesson he received from his father, as George would recount in the last years of his life on a few pages of handwritten memories, the pencilled words fading on yellowed paper found lying at the bottom of a suitcase filled with his personal files. Titled ‘The Boy from Down Under and his Adventures and Life’, it is a statement not only of the significant early influences on what would be an extraordinary journey, but of his clear sense of identity as an Australian, even at the end of a life that took him to the other side of the world.

As much as Charles Finch expected his children to play responsible and productive roles in life, he also wanted them to leave their own mark, which might not necessarily align with his own, on the world. As George reminisced: ‘Our father taught us from our earliest years to love the open spaces of the earth, encouraged us to seek adventure and provided the wherewithal for us to enjoy the quest and, above all, looked to us to fight our own battles and rely on our own resources.’

Some lessons were admonishments for stupidity – pointing an unloaded gun at a friend’s head or attempting to lure out a deadly black snake sleeping beneath the floorboards of his bedroom with a bowl of milk. More profound were the encouragements to explore the natural environment, from the virgin land beyond the boundaries of their rural homestead to the waters of Sydney Harbour where George and Max and their sister, Dorothy, spent summer holidays in the bay below the house their grandfather had built at Greenwich Point, swimming behind shark-proof nets and sailing dinghies across the harbour to the chimney-topped city in the distance.

At its peak in the middle of the nineteenth century, Nubrygyn boasted a schoolroom, general store, blacksmith’s shop and a hotel which the bushranger Ben Hall and his gang once held up, spending a night of merriment on stolen liquor in front of bemused residents. But by the early 1890s, when George was ready to start school, the village cemetery with its handful of gravestones was all that was left besides the still-grand homestead and its prosperous acreage.

The nearest large town was Orange, the birthplace of Banjo Paterson and named incongruously after the King of the Netherlands, formerly the Prince of Orange. George made the twenty-mile round trip each day on his pony to Wolaroi Grammar School, rewarding his steed with Tasmanian apples, but struggling himself to concentrate on the tedious formulated lessons. It was an eternal frustration for his parents who could sense a promising intellect behind the poor grades.

Things were different out of the classroom where George was a natural on a horse – ‘dropped in a saddle at birth’, as his father put it. He and Max were taught how to break and care for horses – they were to be curry-combed gently, brushed, fed and watered before the rider looked after himself, because ‘a good horse is never to be treated as a machine but always as the rider’s best friend’. They were expected to help muster cattle and sheep and ride the boundary fences to repair wires, strung low and tight to keep out the hordes of rabbits that ranged across south-east Australia threatening to destroy threadbare pastures.

George took his father at his word and explored the country every chance he got, often returning late at night and once riding as far as the Blue Mountains, falling asleep in the saddle on the return journey and relying on his horse to deliver him safely to the homestead as dawn broke the next morning.

He quickly became a crack shot with his .410 shotgun, practising on anything that was deemed a pest, from snakes to dingoes, and establishing a flourishing trade in pelts. The brothers even panned for gold in the streams around Mount Canobolas, once finding enough colour and small nuggets to buy new saddles and bridles.

George’s love of adventure also extended to the water, not just the summer expeditions sailing dinghies back and forth across Sydney Harbour, but the romance of the open ocean. As an eleven-year-old he was riveted by newspaper accounts of a North Sea confrontation between the pride of the British navy, the battleship Revenge, and her Russian counterpart, the Czar. During an earlier summer he clambered aboard the famous wool clipper Cutty Sark as she lay at Circular Quay and, much to his mother’s chagrin, asked for a job as a cabin boy. Despite her forbidding it, he sneaked aboard the next day and was given a trial, clambering easily into the rigging but upending a pot of tar – carried aloft by deckhands to coat the ropes and make them waterproof – which smashed onto the polished deck and ended his chance of a life on the high seas.

But Charles Finch’s lessons and expectations went beyond mastering the outdoor skills of rural life, and he encouraged George to read the extensive range of books, mainly legal texts, he kept in his study, hoping it might pique a desire for what he called a ‘serious future’. The boy read, or at least made an effort to plough through, a tome called The Lives of the Chief Justices of England, which extolled the virtues of a law-abiding society and the heroic lives of those who protected it, but it was the science books on his father’s library shelves, collected during his days as a public servant, that caught George’s attention.

George had continued to struggle at school to this point, the lessons in mathematics, French and Latin uninspiring to a youth who yearned to be outside on his horse, but he was suddenly captivated by the experiments created by his father during his days in the field as a surveyor: ‘They awakened in me an abiding interest in science,’ he later wrote.

In particular, he was engrossed by the art of navigation and the use of a sextant for surveying on both land and water. During holidays at Greenwich Point, he would wait expectantly for the sound of cannon fire across the waters of Sydney Harbour to signal that the Sydney Observatory had dropped its 1pm ‘time ball’, the only accurate measure of time in the colony and a navigation aid with which mariners could keep track of Greenwich Mean Time, regulated half a world away on a hilltop in south London. George was equally fascinated by his father’s Atwood machine, a wooden pendulum designed in the eighteenth century to explain Newton’s laws of motion and inverse square laws of attraction and repulsion. What should have been a complex subject for a boy who struggled at school had sparked his brain into action.

Although their age disparity was more akin to that between a grandfather and grandson, the bond between father and son was intensely close. George was imbued with resourcefulness and a desire for achievement, sensing that his character and interests were strongly congruent with his paternal line and, in particular, with his grandfather Charles Wray Finch whose questing journey halfway across the world was a source of wonderment and inspiration.

By contrast, George’s relationship with his mother was, at best, distant. The story of his maternal family was murky and held little interest for him or relevance to his rough and tumble upbringing. He tended to disparage Laura Finch’s fondness for the arts, making this clear in his late-life memoir that paid homage to his father’s influence while scarcely mentioning his mother other than with a backhanded compliment about her singing: ‘My mother was a good and attractive singer but rather over-fond of Mendelssohn’s songs without words but at her very best with Schubert’s songs.’

It would be a misplaced sense of identity, however. Although he clearly embodied his paternal grandfather’s pragmatism and sense of adventure, George also had an ear for language, played the piano skilfully and later discovered a love of reading musical scores as others might read a book. There were physical similarities as well: he inherited Laura’s searing pale-blue eyes and fine-boned features, not to mention her stubborn nature and razor-sharp tongue.

3. A NEW HEMISPHERE

By her own account of their union, Laura Isobel Black was married off to Charles Edward Finch in 1887 to settle a financial debt owed by her bankrupt father. As outrageous as it sounded and without any evidence to suggest a financial link between the two men there was, nonetheless, a ring of truth to her claim.

The beginning of Philip Barton Black’s story was a little like Charles Wray Finch’s, although Black’s journey to Australia was for different reasons and would have a very different outcome. He was the son of a successful Glaswegian cloth merchant, born in 1841 and the youngest of twelve children who, rather than find a place at the back of a queue of siblings, chose to accompany an uncle and emigrate to Australia. At first his enterprising nature seemed to pay off: he registered as an attorney and worked in Melbourne where he found himself a wife named Catherine Cox. Life seemed fabulous until he overreached.

In 1866 Black secured a Crown grant in Queensland on land opened up by the doomed explorer Ludwig Leichhardt, moving his new wife more than 1200 miles north to a property outside Rockhampton where their first child, Laura, would be born the following year. It seemed a strange shift, given that he had no experience on the land let alone the harsh environs of Australia’s north, but most probably he had been enticed by the discovery of gold and later copper which drew men in their thousands, hoping to strike it rich.

The reality must have struck home quickly because within a year he had given up the idea of mining or running cattle and sheep, instead opening a legal office in the tiny town of Clermont that had flourished in support of the human stampede. But the gold seams rapidly ran dry and the town economy stagnated, the law business foundered and by 1869, just as Catherine delivered their second child, Philip Black was in serious financial difficulties. He closed the office and declared PB Black and Co insolvent, quitting the property and moving back to Victoria to be close to his wife’s parents and beneath their financial umbrella.

But the change of scenery did nothing to stem the tide and the money problems grew, just as the family did. By 1877 there were five children (four sons came after Laura) and they moved again, this time to Orange where the New South Wales gold rush had begun and appeared to be more sustainable.

Black registered a new business entity, this time as a commission agent, a middleman specialising in rural property and commodities. Despite his struggles the family maintained a veneer of success, with Laura, then aged ten, taking singing and harp lessons as well as learning French and painting – the sort of skills expected of a young lady of means.

There are few records to shed a light on her father’s business activities other than accounts of court appearances which show his efforts were of little avail. The gold rush had peaked and was now in decline and Philip Black slipped further into debt, his failure as an entrepreneur contrasting sharply with his success as a breeder of children. The combination proved disastrous and in 1881, just before the birth of their eighth child, the courts came to a conclusion about Philip Black and forced him to register debts of £1331 balanced against assets of just £125. He left town.

The family moved once more, this time to the inner-west Sydney suburb of Annandale, but it was a similar sad tale, Black ending up in a legal battle over the ownership of land in the centre of Melbourne – a battle he would ultimately lose. By the time he was finally declared bankrupt in 1892, Philip Barton Black was father to ten children – seven sons and three daughters.

Laura was fourteen when the family moved to Sydney from Orange. Bright and industrious and perhaps driven by the instability caused by her father’s money troubles, she would opt for a career rather than a husband and entered teachers’ college after finishing high school, graduating in 1886 and immediately finding work as a primary school teacher in Orange.

Dark-haired and exotic with alluring eyes and a sharp intellect, Laura Black would have been the centre of social attention in a town packed with mining men and farmhands. Charles Finch, by contrast, was older, authoritative and a man of some importance. Where and how they met has been lost in time but their courtship would be brief. For a young woman to marry a man only two years younger than her own father suggests that there were extraordinary circumstances at play, and lends weight to Laura’s insistence that she was a sacrifice to her father’s sorry financial history.

Whatever the reason for their marriage, it was clear that Charles Finch was besotted with his young wife, not just for her beauty but for her intelligence and presence. Apart from her love of the arts, Laura was a gregarious hostess even though the opportunities for entertaining in Orange were limited. Charles made every effort to turn his somewhat spartan homestead into a home befitting a woman who saw herself as a lady with a social position to uphold. The house at Greenwich Point offered some respite, but it, too, was relatively isolated, one of just a dozen or so houses in a bushland setting with grand verandahs and views across the water to the city, a lengthy boat ride away.

Laura relished her husband’s insistence on formality in the household but without a sufficiently scintillating social and cultural sphere in which to shine, particularly as a mother of three young children, she became increasingly disenchanted until the night in September 1894 that she went to Sydney with friends to listen to a lecture by the controversial English theosophist Annie Besant.

Besant had been a prominent member of the National Secular Society in England and an outspoken women’s rights activist before finding fame by championing the rights of the match girls of East London in their strike of 1888. Her popularity grew as she became a leading member of the Theosophical Society, its name taken from the Greek phrase meaning wisdom of the gods. The society preached universal unity and dedicated itself to ‘the comparative study of religion, science and philosophy and the art of self-realisation’.

Besant’s tour of Australia was a sell-out, her lecture in the then Sydney Opera House – a private theatre at the corner of King and York Streets – reduced to standing room. The small figure of Besant stood alone on the stage and lectured for ninety minutes on ‘the dangers that threaten society’, citing the unequal distribution of wealth as a particular evil and the need for a society without distinctions based on social status, sex or race. Mainstream religion was a destructive force, she argued, and should be discarded for the virtues of philosophy and science and the latent powers of man (or woman).

On the surface, at least, the message appeared to be at odds with the philosophy of Laura Finch and her desire for social recognition (she allegedly carried around a silver box once owned by Charles Wray Finch’s father-in-law, Henry Croasdaile Wilson, containing a stale piece of Melba toast which she would present to hotel staff to indicate how she wanted her breakfast prepared). But the lecture that night clearly challenged her view of the world and she recognised in Besant a kindred soul disillusioned with the status quo. Certainly that was the story perpetuated in family circles: that she sat, mesmerised by Besant’s charisma, and at the end of the lecture whispered the words, ‘I agree with every word you said.’

Within a year Laura found a stage of her own in Sydney (belying her son’s later dismissive judgment), appearing as a soprano soloist ‘before a fashionable audience at the YMCA Hall’, as reported by the Sydney Morning Herald:

Mrs Charles Finch, a new amateur soprano with a fine platform presence, essayed the aria ‘Vers nous Reviens Vainqueur’ (‘Aida’) but was better suited by the valse air from ‘Mireille’. In response to the applause which followed her interpretation of the Gounod melody, Mrs Finch added Meyer-Helmund’s charming song ‘Mother Darling’. A cordial feeling pervaded the concert room throughout the evening and the audience, which was a friendly one, included the Consul-General for France, M. Biard d’Aunet.

The two events would fuel a determination in Laura Finch to escape the isolation of Nubrygyn and she began studying the texts of Besant and her theosophist mentors. Frequent trips to stay with her parents or friends in Sydney once promised an exciting release from the boredom of the bush but, as the new century beckoned and Laura turned thirty, even the music halls and society events in the city seemed to be merely the fringe of possibilities.

Her husband was approaching his mid fifties, a kindly man but set in his ways and social sphere, making the difference in their ages and interests even more apparent. Charles Finch may have been content with his life but his wife wanted to explore the world outside. Europe beckoned and Charles knew he had no choice but to take her.

Charles Finch had other reasons for promising Laura that they would embark on a grand tour of Europe: while his wife’s desire was to explore her potential, he wanted to discover his past. Unlike his father, who had become a soldier and travelled halfway around the world to escape his English legacy, Charles was fascinated by the family, history and determined to reclaim what he could of its status, even though the money, manor house and lands at Little Shelford near Cambridge that flowed from the highly successful ironmongering business of his forebears were now long gone. It fed his sense of place as a man of position and was also embraced eagerly by Laura, herself proud of her maternal link to an ancient titled Scottish family, the Maxwells of Bredieland, after whom her younger son had been named.

So, in August 1902, having secured generous leave from his position at the Land Board, Charles Finch bought tickets for his wife and three teenage children and headed for Europe aboard the steamship Galician. He imagined it would be a twelve-month trip, even describing himself as a ‘tourist’ on immigration documents. Instead, only two of the Antipodean branch of the Finches of Cambridge would ever return to Australia.

4. WHYMPER’S PATH

The gendarmes, necks craned skywards, watched as the two figures inched their way past the famous parapet gargoyles toward the centre of the main face of the great Parisian cathedral of Notre-Dame. It was impossible to identify the climbers, silhouetted against the November moonlight, other than to note they were obviously fit and agile young men who were risking their lives and, more to the point, breaking the law.

Still, it was hard not to be impressed by the feat, the partners in crime climbing straight up the west wall like a pair of spiders, finding hand- and foot-holds in the ancient and pitted stonework. It made interesting an otherwise humdrum evening dealing with street drunks, bar fights and domestic disputes around the 4th arrondissement.

The officers were not the only spectators. A priest stood next to them, transfixed by the scene above. He might have been angry that a pair of fools was desecrating this grand monument to God; instead, he seemed amused by the events.

The two men were both near the top of the towers now, more than 200 feet above the cobbled forecourt. From their lofty position they had sublime views across the twinkling city but their attention was drawn to the knot of spectators gathering below, among them the dark blue cloaks of the police. One of them acknowledged the audience with a wave, prompting a sharp, demanding call: ‘Descendez! Descendez!’

The taller of the two responded cheerfully: ‘Oui, monsieur, nous serons dans un moment.’

Foreigners, probably Englishmen, although the accent was strange. Perhaps they should face charges, or at least a night in the cells to teach them a lesson. The priest seemed to read the change of mood and shook his head. He just wanted them down safely.

The officers weren’t about to challenge a priest from the city’s iconic cathedral. Instead, they watched in amazement as the climbers swiftly made their way back down the wall, hardly out of breath when they reached the pavement a few minutes later.

George and Max Finch grinned, aware of the risk they had taken but politely brushing aside the official admonishment, as they had a few weeks earlier when they’d scaled the 1500-foot chalk headland called Beachy Head, near Eastbourne on the south coast of England. On that occasion the law had been waiting at the top of the climb, at a notoriously dangerous spot known as the Devil’s Chimney, bearing rope and rescue tackle and fearing the daredevils would tumble down the fragile cliff face to their deaths.

It seemed a strange disregard for the law by a young man so attuned to his father’s wishes and principles, but it showed George Finch’s true character: that he would challenge authority when he regarded it as overly bureaucratic, irrelevant or standing in the way of what he wanted to do.

There was a purpose behind the brothers’ madness. George had recently discovered a book called Scrambles Amongst the Alps by the British mountaineer Edward Whymper, famous for being in the first party to climb the fearsome Matterhorn that rose like a stone arrowhead on the border between Italy and Switzerland. The book was regarded as one of the classics of mountaineering literature and George regarded Whymper as his hero, inspired by the Englishman’s well-told stories and determined to emulate his feats, including Whymper’s early jaunts climbing Beachy Head and Notre-Dame.

Although he hadn’t been on the climb of Mount Canobolas that had inspired his brother, Max had willingly taken up the challenge and had proved a nimble and capable compatriot. It would be the beginning of a joyful sibling partnership as they turned from seaside cliffs and city buildings to the real challenge – the mountains of the Alps.

Their rebellious exploits had provided them with a welcome distraction from frustrations within the family. When they’d landed in England in the spring of 1902, the family had stayed near Cambridge, close to Charles’s ancestral home but, despite an initial delight in her husband’s pedigree – including immediately adopting the use of the name Ingle Finch, as borne by the English branch of the family – Laura was not interested in rural English life. She’d pressured Charles to move them to Paris where the theosophist movement was based, particularly as it had become clear that George, who for once sided with his mother, was finding it difficult to settle into the English public school system.

Charles had eventually relented and they’d moved into a grand apartment at 1 rue Michelet, in the heart of the university district, overlooking the spectacular Jardin du Luxembourg. It was the world of which Laura had dreamed while closeted by the stone walls, rough timber boards and dirt roads of Orange. Already a fluent French speaker, she was immediately at home, her entry to French society guided by influential theosophists including the scientist and Nobel Laureate Charles Richet. Within months she was hosting intimate soirées for the city’s bohemian arts community, where her languid beauty and dreamy ways soon became famous.

While his much younger, beautiful wife slipped comfortably into the free-wheeling and decadent lifestyle of Paris, Charles Finch struggled. He was a socially rigid man who was used to being the centre of attention and in control of his environment. In Paris he was lost, nearing sixty and with little purpose other than as an uncomfortable and unwanted chaperon. It was clear that Laura would not easily be moved so, disillusioned, he decided to return to Australia alone.

It is doubtful that Charles sought to discuss the decision with his children or considered taking them home with him. It was clear they were content in their new environment, finally doing well at school, and the boys were excited by the prospect of exploring the mountains of Europe. George never commented about his father’s departure, although the fraught relationship with his mother spoke volumes about the loss.

By April 1903 Charles was back at the New South Wales Land Board, but at the Goulburn office, where he would work for another decade. The newspaper reports of his retirement as a celebrated public servant in 1913 made no mention of a family and none attended the event. Charles Finch would live for another two decades, moving back into the Greenwich house that held only memories of happy summers with a family now settled on the other side of the world.

He would correspond with his children and send money to his estranged wife but he never returned to Europe and did not see Laura or his sons again. Only his daughter, Dorothy, would go back to Australia, in 1925. She would remain unmarried and live with her father for a time before moving to Inverell in northern New South Wales where she worked as a nurse.

Soon after her husband’s departure from Paris, Laura took up openly with a French painter named Konstant and in 1904 gave birth to a son whom she named Antoine Konstant Finch. But who was the father? Certainly not Charles Finch who had left before Laura became pregnant, even though he was noted as Antoine’s father on the birth certificate. The painter was a possibility, as was Professor Richet. For Charles Finch, Antoine’s birth was the insulting coda to a trip that began as a unifying family adventure but ended up with its destruction.

George, then sixteen years old, was devastated and angered by the unravelling of the family and the departure of his father whom he loved. Even though he had no interest in pursuing connections with his father’s English relatives and ingratiating himself with the British establishment, the young man did not understand or approve of his mother’s lifestyle either and regarded her friends mostly as charlatans and theosophy as spiritualist mumbo-jumbo. It’s unlikely he was impressed by Laura’s writings, which included an article titled ‘Should the Dead be Recalled?’, published in the Annals of Physical Science newsletter, and another called ‘The Tendencies of Metapsychism’ in which Laura argued that religion had provided no definitive answers and that science in its various forms was too rigid: ‘Who can say if some day prayer, ecstasy and especially intuition may not take the place of observation, experiment, logic and calculation? We dare affirm nothing, or rather we only affirm that this time has not yet come.’

George derided dialectic argument and philosophy, both pillars of theosophy, accusing Plato and Aristotle of spectacular drawings and lazy observations that relied on ‘preconceived ideas of how things and men ought to behave’, such as the ignorant belief that the heavier an object the faster it fell to earth. If only Aristotle had asked how rather than why an arrow flew:

By and large, all that mankind inherited from Aristotle’s barren inquisition into first causes was his voice of authority; a voice that was to drown out the achievements of Archimedes and the now famous words of Horace … and hold back the progress of man for more than two thousand years until Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo and Newton at last began to break down the wall of the Aristotelian authority. Man is ill-served by dialectics which is the art of proving anything. No wonder Dante consigned Socrates, Plato, Aristotle and others of that philosophical family to the first circle of Hell.

The relationship between mother and son would always be strained, at best, as shown by his terse description of her singing in his late-life reminiscences, and her disloyalty to his father must have been in the back of his mind when he faced a similar situation years later.

Yet as free-spirited as Laura Finch appeared to be, she could also be strict. When the children were young she would insist that they eat whatever food was put in front of them, no matter how long it took. If their morning porridge wasn’t finished, the leftovers would be placed before them for lunch or as their evening meal until they were consumed. The nauseating memory of cold, lumpy porridge would stay with George, even in later life when he often regaled dinner guests with tales of hardship, including the story of the week that he and Max, then in their late teens, were left in Paris to fend for themselves while Laura went away with her friends.

The boys had very little money and ended up at a backstreet restaurant in a less-than-pleasant area of the city where prices were cheap and they could afford to share one of the meat dishes. The meal was surprisingly good so they returned the following night. The same dish, while still tasty, was not as good. Still, it was cheap and satisfying so they returned for a third night. This time, the meal was inedible. They stormed into the kitchen seeking answers and were confronted with the upper part of a human corpse with one arm hacked off. They both vomited before fleeing. As unlikely as it seems, his friends believed the tale to be at least close to the truth from a man not inclined to exaggeration.

Despite incidents like this, the move to Europe benefited George in a significant way. He had struggled in the Australian and English school systems but in Paris his mother found a tutor who was not only able to help him to eventually complete high school but to learn French well enough to qualify to study at the Faculté de Médecine. The transformation of George Ingle Finch (as his mother now insisted on referring to him) from struggling student to academic achiever had begun.

George was still following Whymper’s path in January 1905 when he and Max took a train to the village of Weesen in northeast Switzerland. They were aiming to climb a nearby mountain known as the Speer, as their first tentative step into the Alps. At ‘barely 6000 feet’ it was a relatively modest challenge, but the brothers would soon learn one of the most important lessons in mountaineering – never be complacent.

After buying a map in the village they set off toward the mountain, a popular climb during the summer months when it was regarded as a realistic six-hour hike to reach the summit. But they had arrived in the dead of a European winter and, despite worsening weather and wearing little more than street clothes and shoes, they continued upwards through knee-deep snow. The wind rose after lunch but still they pressed on into the afternoon, even when it became clear that they could not reach the summit before nightfall, let alone return to the safety of the village.

It was 5pm, with darkness descending and their ignorance becoming life-threatening, when they stumbled across a disused wooden hut. The building was almost covered in a thick layer of snow, making it impossible to get through the door, so they forced their way inside through the chimney hole in the roof.

They would spend a sleepless night there, shivering inside the snowbound hut with no warmth and wet clothes and staring at the star-filled skies through holes in the roof. As soon as the sun appeared the next morning they staggered out, stiff and sore, yet not down the mountain, as one might have expected, but continuing upwards. They were determined to succeed, particularly as the weather had cleared and the sun was warm on their sodden backs. The reward was great, as George would later describe in loving detail:

There, bathed in the warm sunshine, all the hardships were forgotten, and we gazed longingly over the ranges of the Tödi and the Glärnisch – real snow and ice mountains with great glaciers streaming down from their lofty crests. Thence the eye travelled away to the rich plains, the gleaming lakes and dark, forested hills of the lowlands, until details faded in the bluish mist of distance.

George was reliving the revelations of Mount Canobolas, only this time he was on the doorstep of his dream to climb the ‘real’ mountains of the Alps. Later that day, after they had descended safely and recovered from their chilling bivouac, the realisation set in that they had learned the first of many valuable lessons: ‘This escapade taught us that mountaineering is a hungry game; that boots should be waterproof, and soles thick and studded with nails; that a thick warm coat can be an almost priceless possession.’

The lessons would come thick and fast over the next few years, as George and Max ‘scrambled’ among the lower slopes of the Alps, usually accompanied by experienced guides – a requirement demanded by their mother. Still, youthful enthusiasm led to a series of close calls from which George was learning the skills that would one day allow him to tackle peaks far higher than the 10,000-foot limit that Laura had also set for her sons.

Both were still studying under tutors so there was a certain freedom in their movements around Europe which fed their growing interest in climbing. Even during a sailing trip around Majorca in the summer of 1906, George and Max spent days scouring the rugged cliffs and mountains of the island while their yacht remained anchored in the bays below.

But their eyes were always on northern Europe where the real challenges lay, and they persuaded their mother to allow them to take a tutor to Switzerland where, between lessons, they climbed Mount Pilatus, a peak just shy of 7000 feet which overlooks the city of Lucerne.

As they climbed higher and higher, the brothers made mistakes that on occasion resulted in serious and even potentially fatal accidents – once almost plummeting to their deaths after slipping on wet limestone slabs, their fall halted by ropes – and yet their survival only added to their youthful disregard for mortality. It didn’t mean that George ignored the lessons of his mistakes: when to climb with nailed boots and when to shed the footwear because ‘stockinged feet’ gave better purchase on the rocks. He grew to appreciate how to use his body, discovering that his legs were his most important asset, providing the muscle power to ascend, and that vice-like fingers to grab hand-holds were preferable to well-developed bicep muscles.

Half a century later, in a speech to the members of the Alpine Club in London, George Finch would reflect on the early experiences, the ‘pure accident’ of his climb up Canobolas and the ‘ineffectual gropings’ of their early daredevil ascents of Notre-Dame and Beachy Head. By comparison, the Alps were exciting and overwhelming in their scale: ‘Up to this time I had no conception of the colossal scale of mountain architecture. But here at last was a yardstick with which to whet my curiosity in this new world – adventure, discovery, new horizons – everything followed after this, almost as a matter of course.’

The two boys, so recently from the Australian bush, were introduced to skiing which they quickly mastered and then used to extend their range of climbing possibilities across the lower slopes of the Alps during subsequent visits. Laura Finch, who occasionally travelled with them to Switzerland, continued to insist that they climb with guides and limited their challenges to smaller peaks. It was frustrating, and they occasionally stole away by themselves, but the period spent learning the craft of mountaineering on relatively easy climbs paid dividends in later years when the challenges grew harder.

One of their most important friendships was with a guide named Christian Jossi, famed for having been in the party of climbers who in 1890 had made the first winter ascent of the ominous Eiger. Almost two decades after Jossi’s climb, George and Max Finch journeyed to the town of Mürren, built in the shadow of the colossus, to meet the legendary guide who had agreed to take the brothers under his wing. It was a relationship that would shape George’s life like few others. ‘Old Christian’, as George and Max would call him, was a quiet, methodical man who embraced the unbridled spirit of the two Australian boys and fed their passion for mountains while instilling a care and respect for the dangers that would otherwise almost certainly lead to their deaths.

The lessons with Jossi took place on the Grindelwald Glacier where George and Max learned to be wary of seemingly innocuous varieties of snow: it might be packed well enough to be the foundation of a step or it might be loose and dangerous, capable of causing an avalanche. Jossi introduced them to the art of wielding a long-handled axe which could be swung with the minimum of effort to chip steps into hard ice. They spent hours cutting stairways, the steps sloping inwards to allow them to stand safely. It was a skill that had been honed by the pioneers of the mid nineteenth century but had been falling out of favour as climbers increasingly turned to summer ascents when there was less ice to overcome. Thanks to Jossi, ice craft would become a hallmark of George Finch’s career. The brothers learned the art of rope safety, too: how to check a slip and hold up a man on the rope, and how to ensure that ropes were kept taut and not looped and tangled. This was a skill that would save their own lives on more than one occasion. They would also be forced to watch, helpless and in horror, as ignorance and haste caused the death of others.

The Strahlegg Pass stood beyond the Grindelwald Glacier at over 11,000 feet, an alien landscape of polished blue-ice walls and pinnacles, crevasses, ice tables and glacial streams from which a climber could see out beyond some of the great mountains of the Alps – the Jungfrau, Eiger, Mönch and Schreckhorn among others. It would become the first exception to Laura’s 10,000-foot limit after the brothers had trained with Christian Jossi.

As it had when they’d hiked up the Speer a few years earlier, the balmy late-summer weather suddenly turned and the young men spent nineteen hours in the middle of a snowstorm. Instead of sheltering and waiting out the storm, fearful that they would freeze to death without the right equipment and clothing, George and Max kept moving through the night, stopping only for brief rests and carefully plotting their way by moonlight and compass. They emerged unscathed, revelling in the fact that they had been able to overcome the conditions, and declaring boldly that with a map, compass and a level head, it was possible to tackle mountain storms and even ‘enjoy’ the experience.

It was also another reminder of the need to equip themselves carefully, not only with the appropriate tools such as ropes and icepicks but with the appropriate clothing: boots large enough to accommodate several pairs of socks and with high toecaps to allow good circulation. Likewise, a woollen sweater worn beneath a windproof jacket made of material such as sailcloth was not only lighter but warmer and more protective than the traditional garb of tweed jackets. Those belonged in a stroll down the high street rather than on a mountainside where they offered feeble protection from the elements and soon became coated in snow, George concluded. Even at this early age the young man could see that convention should be challenged when it made little sense.

There were a few exceptions to George’s distaste for his mother’s circle of friends. Although he took no stock in the theories of spiritualism and the occult that many theosophists espoused, he respected the fact that Laura’s obsession was an intellectual pursuit that she took seriously, not to mention the fact that among the believers were a number of eminent scientists. Richet was one and the British physicist Sir Oliver Lodge was another. Laura participated in psychical experiments, helped to edit research papers and was credited as a co-author with Richet and Sir Oliver of a book titled Metaphysical Phenomena: Methods and Observations.

By 1907, George was getting itchy feet. He had finally completed high school, thanks to the tutors arranged by his mother, and, in spite of his climbing, with grades good enough to enter the University of Paris, la Sorbonne. But he was ready to give up after two years studying medicine, unfulfilled by a science he regarded as too inexact. George was more interested in the black and white of chemistry and sought Sir Oliver’s advice. Should he seek a place at Oxford? No, replied Sir Oliver. Go and study in Zürich.

George didn’t need to think twice. It meant he could pursue a growing love of chemistry, be free of his mother’s bonds and, most importantly, go climbing every weekend.

5. A ZEST FOR MOUNTAINS

For most of the year the Limmat River glides gently, almost silently, through the picturesque centre of Zürich. In late spring, however, when the snows in the Glarus Alps that surround the Swiss capital thaw, the flow can become a rush and then a torrent.

This was the case one night in May 1910 when a group of university students were making their way noisily across the Mühlesteg footbridge that crosses the river, heading back to their lodgings around the university after a night of drinking at one of the many bars in the Old Town.

They were singing loudly, their alcohol-fuelled voices ringing off the water that acted like a loudspeaker in the otherwise quiet night. A strolling policeman decided to intervene and strode purposefully toward them, stopping them at the end of the bridge and announcing that they should quieten down for the sake of the law-abiding citizens already in their beds.

It was a reasonable request but one of the student party, described later as large, objected to the directive. Taking the others by surprise, he picked up the officer and hurled him from the bridge into the river below where, unable to swim, the man was swiftly carried away. Acting instinctively, another of the students took off his shoes and jumped over the ornate balustrade in pursuit of the stricken officer. A few assured strokes, learned from a childhood swimming in Sydney Harbour, and George Finch dragged the policeman, who would otherwise have surely drowned, from the ice-cold river.

The other students, minus the assailant who had fled the scene, scrambled down to the riverbank to help bring the pair back to safety. After a few minutes the sodden, shivering officer recovered his authoritative demeanour, first thanking Finch but then demanding the names of the students and that they identify the offender. None could or, more accurately, would volunteer the name of their drunken colleague, and the officer finally gave up and went on his way. The incident was perhaps one of the first demonstrations of Finch’s a natural instinct for decisive leadership and was brave almost to the point of foolhardiness, leaping into the dark waters with barely a pause to consider his own safety. A few days later the local constabulary hosted a dinner to toast his bravery.

George Finch was then twenty-two years old, broad shouldered and a touch over six feet tall. Fine-featured like his mother, he was as fair as she was dark, although he also shared her piercing pale-blue eyes – ‘glacial’, as someone would call them. It wasn’t just his physical appearance that commanded a level of respect but his manner: assured and charming for the most part, but with a mind of his own and an abrasiveness that sometimes raised the ire of others. And he did not suffer fools silently.