8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

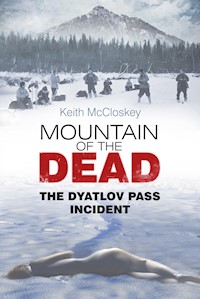

In January 1959, ten experienced young skiers set out for Mount Otorten in the far north of Russia. While one of the skiers fell ill and returned., the remaining nine lost their way and ended up on another mountain slope known as Kholat Syakhl (or 'Mountain of the Dead'). On the night of 1 February 1959 something or someone caused the skiers to flee their tent in such terror that they used knives to slash their way out. Search parties were sent out and their bodies were found, some with massive internal injuries but with no external marks on them. The autopsy stated the violent injuries were caused by 'an unknown compelling force'. The area was sealed off for years by the authorities and the full events of that night remained unexplained. Using original research carried out in Russia and photographs from the skier's cameras, Keith McCloskey attempts to explain what happened to the nine young people who lost their lives in the mysterious 'Dyatlov Pass Incident'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

In memory of

Igor Dyatlov

Alexander Kolevatov

Lyudmila Dubinina

Semyon Zolotarev

Zinaida Kolmogorova

Nicolai Thibeaux-Brignolle

Rustem Slobodin

Yury Doroshenko

George Krivonischenko

Yury Yudin

For Moira, Lucy, Callum and Jack

Front Cover: Top: The Dyatlov group well wrapped up against the elements. Courtesy Dyatlov Memorial Foundation; Bottom: Naked woman. iStockphoto

Back Cover: The last photograph taken of the Dyatlov group while they were still alive. Courtesy Dyatlov Memorial Foundation

Acknowledgements

First and foremost I am grateful to Christopher Jeffery for making the whole project possible as a fair amount of finance for research in the Russian Federation was required. Equally the book would not have been possible without the considerable input from Yury Kuntsevich, Chairman of the Dyatlov Memorial Foundation in Ekaterinburg. Running parallel with Yury’s help was the excellent help and translating carried out for me by Marina Yakhontova. Marina is a first-class translator and is also extremely knowledgeable on the whole Dyatlov Pass story. Her kind assistance and help both during my research in Russia and ‘over the ether’ is deeply appreciated.

I am also grateful to: Alexander Gulikov via the Dyatlov Memorial Foundation for permission to include a condensed version of his theory ‘A Fight in the Higher Echelons of Power’; Yury Yakimov for permission to include his ‘Light Set’ theory, which is a condensed translation of an article that first appeared on www.Russia-paranormal.org. My thanks goes also to Gillian McGregor and Peter J. Bedford (HM Coroner for Berkshire); Natalia Elfimova for her patience and help; Dr Milton Garces PhD; Michael Holm; Dr Gabor Szekely; Pavel Ivanchenko; the director of the Museum at URFU (formerly UPI), Julia Borisovna Shaton, and the curator, Irina Alexandrovna Kashina, who were very helpful and pleasant during our visit; Paul Stonehill and Philip Mantle; Galina Kohlwek; Olga Skorikova and my editor at The History Press, Lindsey Smith.

Special mentions also for: the last surviving member of the Dyatlov group, the now late Yury Yudin, who clarified certain grey areas and answered a number of what must have appeared mind-numbing questions during my research; Leah Monahan for her technical wizardry and unfailing cheerful patience; Triona McCloskey for proofreading. A special thank you to my wife Moira for all her help and unflagging support.

Finally, the British Consulate in Ekaterinburg for the best cup of tea east of the Urals.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Notes on the text

Prologue

1.

Journey to the Mountain of the Dead

2.

USSR and the world in 1959

3.

Ski tourism in the USSR

4.

The Dyatlov group and Mount Otorten

5.

Aftermath and autopsies

6.

What happened – official findings

7.

What happened – alternative locations

8.

What happened – the Yury Yakimov theory

9.

The present

Map 1 Route – Sverdlovsk to Mount Otorten

Map 2 Route – Vizhay to Kholat Syakhl

Map 3 Missile lanes

Map 4 Map of search area

Appendix I Timeline

Appendix II Radiation Analysis Report

Appendix III ‘Light Set’ guidelines

Select bibliography

Plates

Copyright

Foreword

In February 2013 it was fifty-four years since the Dyatlov tragedy, which took place in the northern Ural Mountains. In what appears to be coming to prominence as the Russian equivalent of the Mary Celeste mystery, numerous theories have been put forward to try and explain what happened, but it appears to be a case that almost defies rational explanation. These theories, which try to explain what happened on the night of 1/2 February 1959, range from the quite plausible to what some may think of as the absolutely ridiculous. I have included them all (at least the known theories at the time of writing, including one that surfaced while I was well into the preparation of the book). It is important to keep an open mind and it is also worth considering that the cause of the deaths may involve more than one theory or a combination of theories.

The core of the mystery is not so much how the various members of the party died, but what caused them to flee from the safety of their tent in what appears to have been blind panic, fearing for their lives. There is also another line of thinking, which suggests that the deaths occurred elsewhere and their bodies were deposited on the slopes of Kholat Syakhl (Mountain of the Dead). The real problem is that there is very little evidence to go on, everything is conjecture. Also, part of the problem in finding an answer is the nature of the former Soviet Union with its mania for secrecy and security. Despite the fall of the former USSR, the opening up of archives and a different outlook among the younger generation, old attitudes still persist in many areas of officialdom.

I have also tried to give an idea of the background in which the tragedy took place. In other words, the Cold War, which dominated everyone’s lives in the East and West at that time. I have also given a brief explanation of the part that ‘ski tourism’ played in the Soviet Union.

The only thing certain is that nine young people in the prime of their lives died dreadful deaths and, like the Mary Celeste, it is probable that the truth of what actually happened will never be known for sure.

Notes on the text

* In many articles and publications the word ‘tourism’ is mentioned and the Dyatlov group are referred to as ‘tourists’ or ‘sports tourists’. This was a loosely defined term and a condensed definition of it in 1969 was: ‘Tourism includes journeys with the aim of active rest and better health and performing socially useful work. An important part of tourist activity is moving around on foot, skis, bicycle or boat and overcoming natural obstacles often in extremely difficult climatic conditions and even in dangerous situations, e.g. mountaineering or rock climbing … Many tourist journeys involve self-service, such as arranging a camp, camp-fire, food and washing. Sporting tourism also includes mountaineering and orienteering. The All-Union Sports Classification details the complexity of routes, the number of journeys, the length of the journeys and the difficulty of natural obstacles that the tourist has to negotiate in order to gain a ranking.’

G.D. Kharabuga, Teoriya I metodika fizicheskoi kul’tury (Moscow 1969)

* 41st Kvartal – (meaning ‘quarter’ or ‘square’) kvartal in forestry is part of a forest area defined by artificial fire breaks or natural terrain features such as rivers. Kvartals are an important element in cadastres, mapping, economics and forestry management. Kvartals may be of different sizes e.g. 4x4km, 8x8km or larger depending on the size of the forest. Kvartals are numbered in a direction from NW to SE. Quarter poles at lane crossings have numbers on their sides also oriented in the NW and SE directions. Rangers, geologists and tourists use them to find their locations on maps. The 41st Kvartal referred to in the text is a woodcutter settlement in the 41st Forest Kvartal.

* Kholat Syakhl – strictly means ‘Dead Mountain’ in Mansi but, with the deaths that have taken place there, it has come to be known as ‘Mountain of the Dead’.

* Taiga – used to describe the Boreal Forest. The Taiga is also a biome or ecosystem that consists mainly of coniferous forests and covers a vast area in northern Russia.

* Gulag – the acronym (in Russian – Glavnoe uplavrenie lagerei, meaning Main Camp Administration) for the system of prison camps across the USSR used to incarcerate criminal and political prisoners who were used as slave labour.

* Names – wherever possible I have avoided use of the traditional Russian patronymic and used simplified first names in order to make reading easier.

* Yekaterinburg/Ekaterinburg – there is not enough space to go into the various reasons why there are two different spellings for the city: I have chosen Ekaterinburg. Between 1924 and 1991 the city was names Sverdlovsk.

* Oblast – government administrative region.

* Mansi – tribe of the northern Urals region.

* Khanty – tribe of the northern Urals, related to the Mansi.

Prologue

In January 1959 ten students from Ural Polytechnic Institute in Sverdlovsk set out on what they hoped would be an exciting journey and a test of their skills in the remote northern Ural Mountains, nearly 400 miles north of the city where they lived and studied. Although it was midwinter and the conditions would be harsh, the trip was to be a break from the hard daily routine of their studies. The leader of the group was Igor Dyatlov who had only just turned 23, an affable and highly experienced skier, hiker and orienteer. There were two strong-willed girls in the group: Lyudmila Dubinina and Zinaida Kolmogorova. There were also another seven males: Yury Yudin; Rustem Slobodin; Semyon Zolotarev, a tough Second World War veteran and expert in unarmed combat; Alexander Kolevatov; George Krivonischenko; Yury Doroshenko; and Nicolai Thibeaux-Brignolle, who was born in one of Stalin’s Gulags where his father, a French communist, had been imprisoned and executed.

The whole group were all very fit, experienced hikers and skiers. Only the previous year, Igor Dyatlov had led a party on the same route, so they were confident that there would be no problems encountered that they could not deal with.

They left Sverdlovsk and travelled north by train, lorry and then finally on foot and skis. On 27 January they reached an abandoned village of wooden houses, which had previously been used by geologists. They spent the night there and it was here on the following day (28 January) that one member of the group, Yury Yudin, decided to turn back because of illness.

Their target was to reach the 1,234m Mount Otorten (translated as ‘don’t go there’ in the local Mansi language), but they ended up on the slopes of the 1,079m mountain named Kholat Syakhl (translated as ‘Mountain of the Dead’ in the local Mansi language).

Up until 28 January 1959, everything can be independently verified about the journey of the Dyatlov group. Beyond that date, and despite the presence of a group diary and photographs, nothing can be verified.

1

Journey to the Mountain of the Dead

The events leading up to and the night of 1/2 February 1959 have been reconstructed, as far as possible, from what was found by the search parties and the last entry in the Dyatlov group’s diary for 31 January 1959, which was made by Igor Dyatlov. This chapter is also a reconstruction of what happened from the official point of view.

On 23 January 1959, the group of ten skiers spent the day in Room 531 at Ural Polytechnic Institute (UPI) in Sverdlovsk. They were all members of the UPI Sports Club and were frantically packing their rucksacks and getting their equipment ready as they had a train to catch. Assisted by the zavchoz, the university’s head of provision distribution, they packed items including oatmeal, 3kg of salt, knives, felt boots and all the other accessories necessary for the journey.1 The talk was on a very superficial level and, despite their anticipation of a journey they were all looking forward to, tempers were starting to fray. Zina Kolmogorova expressed her frustration at not being able to pack a spring balance. Rustem Slobodin asked whether or not he would be able to play his mandolin on the train – to which Zina sharply replied, ‘Of course!’ They considered the mandolin to be one of the most important pieces of equipment for the journey, as it would be their main source of entertainment. Luda Dubinina counted the money they had pooled together. Money was tight. They had been given 1,000 rubles by the Trade Union Committee at the university but they had to put in their own money as well. They were in high spirits and looking forward to their expedition, despite the last minute rush to ensure everything was packed and that they had not forgotten any food or equipment. That day, 23 January, was the first day on which an entry was made in the group’s diary and in which they took turns to make the entries for the period of the expedition. The first entry was made by Zina; she wrote that she wondered what awaited them on the trip – although at that time she could have had no inkling of what was to happen.2

Their planned route was by rail to the town of Ivdel, via Serov, and then a bus would take them directly north to a small settlement at Vizhay on the River Auspia. From Vizhay the group would proceed on a hired truck, then on foot and skis, to Mount Otorten. The whole route from Sverdlovsk to Mount Otorten, with the intermediate stops, was more or less directly north–south and approximately 340 miles (550km) as the crow flies. From departure to their arrival back in Sverdlovsk, the trip was expected to take twenty-two days.

At this stage another person was expected to join the group, Nicolai Popov, nicknamed ‘the morose fellow’, who had agreed with the group leader Igor Dyatlov to provide his own supplies and equipment. Popov had already graduated from the university and was not a student. Fortunately for him he missed the train.

The group set out by rail from the main railway station in Sverdlovsk for the 201-mile (324km) journey north to the town of Serov. The young men in the group made a solemn promise to the two girls that they would not smoke for the entire trip. Zina doubted very much that they would have the willpower to keep their promise for so long. Once the train set off on the long journey north, they settled into their seats and Rustem Slobodin took out his mandolin. Together they sang songs they knew and composed new ones. Semyon Zolotarev was not well known to everyone in the group, but he fitted in quickly as he had a vast store of songs, many of which the students had never heard before. Because of his much greater experience of life, particularly as a front-line soldier in the Second Word War, as well as having been a Komsomol (Soviet youth organisation) leader, he was duly accorded respect by the others. Much has been speculated about Zolotarev who, like the story of what happened to the group, in many ways remains an enigma.

As they sang along to the the mandolin, darkness descended as the train continued its long journey north. They looked out of the window at the seemingly never-ending Taiga, which spread to the Ural Mountains on the left and on the other side to the vast empty spaces of Siberia. As well as the occasional appearance of a small severny (settlement), they passed several military bases (or areas related to the military) between Sverdlovsk and Serov. During the Nazi attack on the USSR in the Great Patriotic War (1941–45) – as the Second World War was known to the Russians – much of the military production (e.g. tanks and aircraft) was pulled back to the east of the Urals, far away from the Nazi advance and out of the range of Nazi bombers. With the advent of the Cold War, most of these facilities remained where they were, with expansion taking place and the addition of facilities to take account of the new atomic age. There was a major plutonium-producing complex at Kyshtym between Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk, which lay in the opposite direction (south) to which the Dyatlov group were travelling.3 The Kyshtym plant was where George Krivonischenko had been involved in the clean-up after the 1958 nuclear accident. There were other facilities more or less on the route north on the group’s line of travel. These included a gaseous diffusion production plant for plutonium U-235 at Verkh Neyvinsk to the north of Sverdlovsk,4 and a large facility for the production and storage of nuclear warheads at Nizhnyaya Tura.5 Travel in these areas was severely restricted and the presence of so many nuclear, military and associated facilities has a bearing on some of the theories relating to what happened to the Dyatlov group.

By 3 a.m. on the morning of 24 January, having exhausted their stock of songs and being exhausted themselves, Zina recorded in the diary that the rest of them had all fallen asleep as she surveyed the darkness outside the train window.

After leaving Sverdlovsk well behind them, the train pulled into the town of Serov at 7 a.m. on 24 January. Both Zina and Luda mention that they had travelled with another group of hikers from the university, led by Yury Blinov, who had left at the same time as them. Luda had suspected that Zina was keen on a male member of the Blinov group, as she (Zina) appeared upset when the two groups later split up. The two groups were well known to each other and Igor Dyatlov had given his radio set to the other group. However, upon their arrival at Serov, the reception the station staff gave them caused all feelings of empathy and friendship to disappear. As, despite the eary hour, they were not allowed in to the station building. In the diary, Zina described somewhat sarcastically the response from the staff as ‘Hospitality’. A policeman had stared suspiciously at the group and they must have felt intimidated, as Zina further noted in the diary that they had not broken or violated any law under communism. The atmosphere of intimidation must have begun to annoy George Krivonischenko as he started singing, which was enough for the policeman to grab him and haul him away. The police told the group that Section 3 (of local railway regulations) forbade all activity that would ‘disturb the peace of passengers’. Again Zina made a diary entry, which stated that Serov must be the only station where songs were forbidden. Eventually George Krivonischenko was released and the matter was settled amicably. Whilst it is possible to read something into the behaviour of the police towards the group, it is more likely that the group were boisterous and in good spirits in the early stages of their journey, which attracted the attention of provincial officers with too much time on their hands. Furthermore, the group had passed through an area containing sensitive military establishments and were starting to approach another area (around Ivdel) that contained numerous prison camps. In these circumstances, and at that time in a state obsessed by security, strangers automatically brought suspicion on themselves by their very presence.

Serov was more or less halfway from Sverdlovsk to Ivdel. The group had more than eleven hours to kill before they could take the next train to Ivdel, which left Serov at 6.30 p.m. They were warmly welcomed at a school close to Serov railway station. A janitor (zavchoz) heated water for them and made arrangements so that they could store their equipment. It was a free day for the group and the diary entry for that day was made by Yury Yudin. Yudin had wanted to visit a natural history museum or a local factory. Visiting a local factory may seem an odd choice as a way to pass the time but it was very much in keeping with the ideal of the young communist Yudin, who, although studying at a higher institute of learning, would still wish to express his solidarity with the factory workers and would have been welcomed by them.

However, much to Yudin’s disappointment, the first part of their day was spent in checking their equipment and going through their drills and training. At 12 p.m. when the first part of the school day was over, the group organised a meeting with the schoolchildren. The meeting was held in a small cramped room where the children listened silently as Zolotarev explained what sports tourism was, and what they were doing on their trip. The children were possibly a little apprehensive of Zolotarev, but when Zina started talking they became more animated. She spoke to them individually, asking their names and where they were from, and was a firm favourite with the children as they asked her endless questions in return. After two hours, the children did not want the group to leave. They wanted to know each minute detail about the trip, from how the torches worked to how the tent was set up. Eventually the time came for the group to gather their equipment and make their way to the station for the train to Ivdel. The whole school went to the station to see them off. The children were upset at the group’s departure, with some of them in tears and many of them asking Zina not to leave and to stay with them. Zina asked the children to make sure that they behaved well and studied hard. However, despite the emotional farewell, the group’s problems with railway stations and the police had not ended. A young alcoholic accused someone in the group of stealing his wallet, with the result that the police were called. Luckily nothing came of it and the group were allowed to proceed without any further restrictions, much to their relief.

The journey by train to Ivdel was five and a half hours long. They settled down to talk (Zina proposed a discussion on the nature of love) and again to sing songs, accompanied by Rustem Slobodin’s mandolin. Some members of the group used the time to revise for their exams. Their sustenance on this part of the journey consisted of garlic bread without water. The town of Ivdel was the last major point of contact with civilisation before they set out on the journey north into the more remote Siberian Taiga and the mountains of the northern Urals. The town itself was the centre of the Gulag camp system for the area. At one point there were almost 100 camps and associated subcamps of varying sizes in the vicinity of Ivdel. The town is situated on the Ivdel River near the confluence of the Lozva River, 332 miles (535km) north of Sverdlovsk. It had been the first wooden fortress east of the Urals, built in 1589, and became a gold-mining settlement in 1831. The first Gulag was established there in 1937 and eventually the population grew to between 15,000 and 20,000 inhabitants, a figure which has remained fairly constant.6 Many prisoners who were released from the nearby camps decided to stay in the town as they had nowhere else to go. The same applied to the prison staff. A number of former staff who had finished working at the camps also decided to settle in Ivdel for the same reason – that they were familiar with the area and had nowhere else to go. The result was that, by 1959, a large segment of Ivdel’s population was a strange mixture of former guards and the formerly guarded.

On arrival just after midnight on the night of 24/25 January the group alighted at Ivdel railway station. They found a large waiting room where they stored all their equipment and took turns to keep watch while they awaited the bus for Vizhay early the following morning: Sunday 25 January 1959. A comment made in the group diary by Yury Yudin is noteworthy: that they had ‘total freedom of action’ at the station at Ivdel. This was no doubt a reference to their two unfortunate previous encounters with the police at Serov station.

On their arrival at Ivdel, the group were 90 miles (145km) from Mount Otorten. After the short wait they took a bus to Vizhay where they arrived at 2 p.m. They decided to spend the night of 25/26 January in Vizhay before proceeding to the next point. Their accommodation was described by George Krivonischenko as a ‘so-called’ hotel, which must have been very basic even by the standards of the austere Soviet Union in the 1950s. There were not enough beds for the ten members of the group so they slept two to a bed, with both Sasha (Alexander Kolevatov) and Krivoy (George Krivonischenko) gallantly sleeping on the floor. Despite the inadequate accommodation, they slept well and rose at 9 a.m. on 26 January, only to find that the outside temperature was -17ºC and a small window had been left open during the night, forcing them to get out of bed in freezing conditions. They relied on the hotel for breakfast and were given goulash and tea. Igor Dyatlov made a comment about the lack of heating in the ‘so-called hotel’, joking that if their tea was cold they could always go outside the hotel and it would soon warm up enough for them to drink it! They then arranged to get to the next point on their journey, the 41st Kvartal (this was a camp for geologists and workers in the area), by road in an open flat-bed type GAZ-63 truck that was organised to take them. A photograph of eight of the group shows them all sitting on the back of the open truck with wooden slatted sides exposed to the elements. Yet they were all well wrapped up against the wind and cold and again seemed in good spirits. The truck eventually left Vizhay at 1.10 p.m. on 26 January. Despite their layers of clothing the group were freezing on the three-hour journey and tried to occupy themselves by singing and animatedly discussing various topics, which ranged from love (a favourite topic of Zina’s) to the nature of friendship and the problems of finding a cure for cancer. The bitter cold on the truck affected Yury Yudin badly and despite trying to hide under a makeshift tent they had made to keep off the wind, he developed a chill with lumbago and an acute pain in the leg.

At the 41st Kvartal they were glad to be able to get off the truck. Even though it was a remote area, there was a hostel there, which was operated with a dormitory system for the geologists and workers in the area to stay. However, the group were given their own private room probably due to deference to their status as educated students.

Whilst there they spoke to the workers and in particular befriended an older man called Ognev who made quite an impression on George Krivonischenko.7 Ognev also made an impression on Luda who was keeping her own private diary (apart from the group diary that everyone had access to), in which she gave a fuller description of Ognev. On arrival at the hostel they cooked lunch and then rested. Films were available to watch in the hostel and some of them watched a film while the others occupied themselves individually. Rustem played his mandolin while talking to Nicolai. Krivonischenko spent his time checking the equipment to make any necessary adjustments to the packing. Krivonischenko had made the diary entry describing their arrival at the hostel and how they spent their time on 26 January, but there is a single cryptic comment in the diary for that day made by Nicolai Thibeaux-Brignolle in which he states: ‘I can’t although I tried.’

There is no further detail and no later comment regarding this single-line entry, but Nicolai is thought to be possibly referring to having started smoking again despite the solemn promise made by himself and the other males in the group that they would not smoke for the entire trip.

The next day, 27 January, the diary entry described the weather as ‘good’. The wind was behind them and they reached an agreement with locals at the 41st Kvartal for a horse and a guide to take them to the next point on their journey (an abandoned settlement), which was approximately 15 miles (24km) further on. While waiting for the use of the horse they helped a local by the name of Slava (described as ‘Grandfather Slava’) to unload hay from a carriage. Some of the boys rewrote a song and then started singing with some of the locals and workers. One man in particular was described as singing beautifully. A number of forbidden songs were also sung, but these only by the workers,8 as the comment in the group diary was ‘We heard …’ rather than any reference to any of the group singing the songs themselves or joining in. Nevertheless, they obviously knew that the songs were illegal as they used the term ‘illegal’ to describe them. It is possible they either joined in or sang some themselves, but would have made no written reference to having done so for fear of possible censure if anyone in authority read their diary on their return. A further comment was also made in the diary regarding these songs as ‘Article 58 Counter-Revolutionary Crimes’.9

The group departed from the 41st Kvartal at 4 p.m. on 27 January, with this 15-mile (24km) section of the journey on foot made much easier by having the horse pull their packs and equipment on a cart. Before departing they had bought loaves of soft warm bread and ate two of them on the journey. The second severny (settlement) they reached was abandoned and derelict, but Ognev had told Igor Dyatlov where they could find a habitable dwelling to settle for the night to break their journey.

It was at some time during this fifth day (27 January) of their journey that Yury Yudin’s illness worsened. He had fallen ill on the truck travelling from Vizhay to the 41st Kvartal but had decided to tough it out and continued with the group as far as the second severny, as he wanted to collect some geology samples and then return to Sverdlovsk. The pain in his leg was getting worse and it had become apparent that he would be unable to meet the more physical demands of the rest of the journey in the mountains. He was diagnosed eventually with acute radiculitis. The second severny, which as mentioned was now abandoned, had been a settlement used by Soviet geologists while they carried out research locally. Yury Yudin was an economist but had an interest in geology and, despite his illness, he obviously felt there was some value in continuing with the group in order to search out samples around the settlement to take back with him to the university.

The horse pulling the group’s backpacks and equipment moved slowly, yet the group was able to travel faster than if they had been carrying the stuff themselves. Despite complaints about the slowness of the horse, they covered 4 miles (8km) in two hours, reaching the River Ushma. By now, darkness was falling. Some members of the group had moved on ahead to reach the abandoned settlement before darkness fell completely. They wanted to find the house described to them by Ognev as it was the only place suitable to rest for the night as all the other buildings were in a bad state of disrepair, with a number of them literally falling apart. In the event, they managed to find the house described by Ognev in the complete darkness, out of the twenty-five houses in the settlement, and started a fire to keep warm. Several of them pierced their hands on old nails in the wood as they were gathering it for the fire. The horse and cart, with Yury Yudin sitting on top in order to spare his leg pain, along with the remaining members of the group, eventually arrived at the abandoned settlement later that evening. Once they had settled in, they sat by the fire and talked and sang until 3 a.m. the following morning (28 January) before going to sleep.

The first two members of the group to awaken on 28 January were George Krivonischenko and Alexander Kolevatov, who then woke the others. The weather was good, with clear visibility. Although the temperature was -8ºC, it was not excessively cold for the time of year and the area. After they had eaten breakfast, Luda made adjustments to the mountings on her skis and Yury Yudin went outside into the area near the settlement to see if he could find any minerals. There was nothing of any interest to him apart from pyrite and quartz veins in the immediate surrounding area. It must have been a relatively cursory search as he was to leave the group that day and return to Sverdlovsk on account of his illness. He possibly felt too ill to search properly, but at least would be able to show on his return that he had made an effort despite being unwell. Again, this display of stoicism would have fitted in well with the ideal of the young communist – who is prepared to do what is expected of him or her, no matter what troubles may have to be faced.

The first part of the diary entry for this day (28 January) was made by Luda, who was obviously very fond of Yury Yudin and sorry to see him go. Luda states that it was a pity (‘especially for me and Zina’) that Yury Yudin had to return. Luda appears to have been more demure than Zina. One photo shows Luda embracing Yury Yudin in a genuine display of affection for him before he leaves, while another shows Zina touching Yudin’s face as a gesture of affection just as he is preparing to make his departure. After leaving his companions behind, Yury Yudin would dwell for the remainder of his life on what happened to them and how fortunate he was to have escaped their fate.