Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

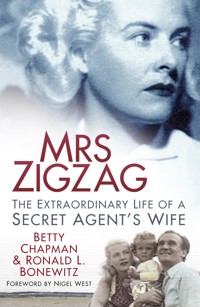

When Betty Farmer married double agent Eddie Chapman, Agent Zigzag, she knew her life would never be ordinary. Yet even before her marriage to Eddie, her life involved incendiary bombs, serial killers, film roles and love affairs with flying aces. After her marriage she coped with Eddie's mistresses, his criminal activities, separations and personal traumas. Coming from humble origins, Betty would, in time, own a beauty business, a health farm and a castle in Ireland, become the friend and confidante of film stars and an African president, and the honoured guest of Middle Eastern royalty. In an age where women were still very much second-class, she became a perfect example of what, in spite of everything, was possible. Much has been written about Eddie Chapman, films have been made, television programmes produced. Yet alongside Eddie for most of his extraordinary life was an equally extraordinary woman: Mrs Zigzag. This book tells the story of the Chapmans' often fraught but ultimately loving relationship for the first time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 303

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Lilian Verner-Bonds, who encouraged the writing of this book.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the Chapman family, and especially to Betty’s daughter, for the use of documents, tapes, photographs and other materials relating to the life of this extraordinary woman. Thanks also to The History Press, and especially to Mark Beynon, and to Nigel West for his foreword.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

Prologue: Agent Zigzag

1. Eddie is dead, long live Eddie

2. Spitfires, sabotage and serial killers

3. Round and round she goes

4. Beauty and the sea

5. Ghana

6. Kwame Nkrumah, I presume

7. A colourful bunch of villains

8. Double Cross on Triple Cross

9. Shenley

10. My home is my (Irish) castle

11. A healthy business

12. Eddie’s last battle

13. Reflections

Notes

Plate Section

Copyright

FOREWORD

BY NIGEL WEST

Early in March 1980 I found myself in Claygate, south-west London, in the company of an elderly British army officer, Major Michael Ryde, who had fallen on hard times. I was meeting him because I had heard that during the war he had served in MI5 as a Regional Security Liaison Officer, the post held by the organisation’s representatives who acted as an intermediary between the counter-espionage branch, designated B Division, and individual military district commanders. Over a cup of coffee served by his long-suffering partner, Marjorie Caton-Jones, Ryde recalled his recruitment into the Security Service and happier times, when he routinely had been engaged in the most secret work, much of it involved in the handling of double agents. As he gained enthusiasm for his subject, and his improving memory allowed him to add the kind of detail that ensures authenticity, these revelations visibly moved Marjorie who confided to me later that in all the years she had lived with the veteran, he had never mentioned his wartime intelligence role. As a professional journalist of long standing, having worked on The Sunday Telegraph for years, she had developed a skill for listening, and on this occasion she sat rapt as the man she had known and lived with described a part of his life that hitherto had been entirely unknown to her. Later, she would reproach herself for having failed to apply her inquiring mind to the one man who had played such an important part in her recent life.

Major Ryde’s story largely revolved around his relationship with a Nazi spy, code named Fritzchen, who had been expected to parachute into East Anglia towards the end of December 1942. Much was already known about him at MI5’s headquarters in St James’s Street, information that had been gleaned from ISK and ISOS, the cryptographic source based on intercepts of the Abwehr’s internal communications. The German training school in Nantes, where Fritzchen had been based, was connected to Berlin by a radio link as the occupiers learned to distrust the French landline telephone system. With regional operations supervised in every detail from the Abwehr’s main building on the Tirpitzufer, the airwaves were entrusted with the most banal details of the progress made by agents undergoing preparation for missions in enemy territory. Fritzchen was known to be a British renegade, paid a regular monthly salary of 450 Reichsmarks, with an agreed bonus of 100,000 Reichsmarks, then valued at £15,000, if he pulled off his sabotage assignment successfully. As well as mentioning his contractual arrangements, the intercepts listed the two aliases he would adopt in England, the frequencies of his wireless transmitter and the detail of his dental repairs.

In Fritzchen’s case, his planned departure was delayed by a training accident when he had been injured while practising a parachute drop. After several false alarms, Ryde had been alerted to the imminent arrival of the much-anticipated spy on a clandestine Luftwaffe flight from Le Bourget in mid-December, and he finally landed near Ely on the night of 20 December, three days late. Ryde had been waiting patiently for this news, but he could not be certain of the exact location of the drop-zone, nor the likely attitude of the spy. Worst case, Fritzchen, who was known to have a criminal past, would prove to be intransigent and uncooperative, making MI5’s task more complicated. On the other hand, he might be wholly willing to collaborate, and then there was always the middle path, of the spy conditioned to self-preservation, who would take on whatever guise that would save him from the gallows.

Ryde recalled the moment, in Littleport’s tiny police station, that the Chief Constable of Cambridgeshire had ushered him into the interview room where he was confronted with Fritzchen, the first Nazi spy of his acquaintance, and who was equipped with £1,000 in notes, a loaded automatic and a suicide pill. This would be the beginning of an extraordinary adventure that would end in January 1946 when MI5 learned that the double agent known to them as Zigzag intended to disclose his remarkable story in the French newspaper L’Etoile du Soir. The result was a criminal prosecution at the Old Bailey on charges under the Official Secrets Act in an attempt to remind Zigzag, and other double agents also tempted to recount their experiences. MI5’s leading lawyer, Edward Cussen KC, discussed the options at length with his Director of B Division, Guy Liddell, who confided to the diary he dictated every evening that authority had been given for Cussen to travel to Paris to investigate what was regarded as a significant breach of faith.

Cussen returned to London with the evidence required to arrest Zigzag, and it was intended that a private session in a magistrate’s court, held in camera, with a stern lecture from the bench, would act as a deterrent, not just for Zigzag, but for any others interested in publishing indiscreet memoirs. However, MI5’s intentions were thwarted when, to the surprise of the prosecuting counsel, the defence had called Major Michael Ryde, who had testified on oath at his trial at Bow Street Court on 19 March, without any approval from MI5, that the defendant was ‘the bravest man he had ever met’ and that, far from deserving to be in the dock, he should receive a medal. Thus ended Ryde’s career in the Security Service, and gave Eddie Chapman the confidence to tell his truly incredible tale.

Thanks to Michael Ryde, and an introduction provided by him, I was soon sharing coffee with Eddie Chapman and his equally extraordinary wife, Betty, at their apartment in the Barbican. Always modest about his own exploits, the legendary double agent regarded his encounters with MI5 as only a small part of an extraordinary career. Fortunately, Betty knew better!

INTRODUCTION

Iwas introduced to Betty and Eddie Chapman several years before Eddie’s passing in 1997, by Lilian Verner-Bonds, a mutual friend and a long-time friend of the Chapmans. One of my great regrets is that I didn’t know more about Eddie at the time. Sketchy details of his past were known, but my recollection of that first meeting is of a pleasant, late-middle-age couple in their comfortable but far from extravagant surroundings. We shared a pleasant tea together, during which the conversation passed as nothing remarkable, leaving me with a recollection of a nice gentleman who said very little. As the years passed, so too Eddie passed away. I was encouraged over a long period to start writing the story of his wife Betty, which is equally remarkable. The time was never right, until now.

This book was constructed from numerous interviews, documents, Betty’s notebooks spanning several decades, and from taped reminiscences of Betty and Eddie, which were generously provided by the Chapman family. Other information has come from documentary sources. In her nineties, Betty is still bright and lucid, with an excellent memory. Where possible, this story has been told in her own words: my role is principally that of narrator. Where Betty’s language may, in a very few places, seem ‘politically incorrect’, it must be remembered that she is a woman of her generation: a woman of substance by dint of her own efforts, and a British woman living through the transition from British Empire to Commonwealth. I have never, through long interviews and in examining innumerable pages of her notes and writings, seen the faintest hint of prejudice. This is especially true as she describes her adventures in Africa and the Middle East. She simply reports what she has seen and done, and takes all who she met as they are, on their own merits.

It may also be asked as to why she didn’t have more detailed knowledge of some of Eddie’s post-war activities. There are several answers to this. First, although Eddie was a consummate storyteller – often not bothering too much with accuracy – he was careful about what he told. He survived as a double agent by knowing when to keep his mouth closed. As, indeed, he did when I first met him. While he might weave fascinating tales about his adventures, there were many things about which he had nothing to say – especially in the presence of Betty. This is the second point: Eddie was always very protective of his wife, and never would have put her at risk by telling her too much. It is also important to remember that in British society of the time, even into the latter half of the twentieth century, it was not unusual for a wife not to know her husband’s income – or for that matter even what he did for a living. In this context it is not surprising that Eddie’s activities when he was away from Betty still are not fully known to her. There is no doubt that she was his anchor and he wanted her involved in many of his ventures – and to be involved in hers. But this was far from the sum and total of Eddie’s life, or Betty’s.

Eddie Chapman was a man as complex as the space shuttle, but with many components that worked in direct opposition to each other. How it must have been to have lived with such a man is difficult to imagine. Who could have imagined that this young farm girl from the back of beyond would become the honoured guest of Middle Eastern royal families, the confidante and hostess of an African president, the friend of film stars? Yet Betty Chapman, née Farmer, not only grew as a person while with this man, but in her later years when I met her turned out to be a delightful and thoroughly charming lady, whereas other women under the same circumstances might have grown dark and embittered.

Many readers will ask themselves as they progress through the book: ‘Why on Earth did she stay with him?’ The answer is as complicated as their relationship. Because both Eddie and Betty were extraordinary people in their own right, their relationship cannot be judged by the standards of ‘normal’ relationships. Eddie was more like a force of nature: the torrent of water flowing around the rock that was Betty – each in their own roles.

The counsellor and therapist Lilian Verner-Bonds, a long-time friend of the Chapmans, adds: ‘Betty was never Eddie’s victim. She had the same strength and steel as he did. That is why they were perfectly suited, and she was able to give him the support she did. They were two peas in a pod.’

Some readers may be tempted to make judgements about Eddie Chapman based on Betty’s experiences related in this book. My advice is: don’t. There is no doubt that Eddie was a difficult man, but from everything I know about him, and from the brief time I spent with him and Betty before his passing, he was not a bad man. Indeed, there will be more than one reader of this book who is alive today because of him, and at considerable risk to his own life. The total number is likely to run into thousands.

Betty herself is a deeply spiritual woman, and has always had the feeling that no matter how it came about and whatever experiences resulted, she and Eddie were meant to be together. This has been emphasised to me time and again by Betty during the preparation of this book, and I have not the slightest inclination to dispute it. She views their life together as their mutual karma. Karma has many definitions, but the only one that really matters for Betty is this: ‘I just felt like his life was his karma, so my life was my karma. Your karma means that it’s what was meant to be, what you were fated to do. Because if you believe that you have lived before, this is the continuation. This is something you’ve come back to do, whether it’s pleasant or unpleasant.’

One of Eddie’s biographers went to the heart of the matter: ‘How Eddie and Betty got together is one of the more implausible stories in a lifetime of unlikely happenings. That she stayed with him – as Eddie faced up to his demons – is the most extraordinary thing of all.’

It is hoped that this book will shed light on that very thing.

Dr Ronald Bonewitz

Rogate, England, 2013

PROLOGUE: AGENT ZIGZAG

Zigzag was the name given by British Intelligence to one of the most audacious double agents of the Second World War – Arnold Edward ‘Eddie’ Chapman.

Eddie had been born in Sunderland to a middle-class professional family but his father, a marine engineer, had spent most of Eddie’s childhood away at sea, and his mother had struggled to bring up her two boys more or less alone. When Eddie was young, he was an apprentice in the shipping industry with Thompson’s shipbuilders. Whilst he was there he saved a young man from drowning. Yet when he was interviewed about the incident he denied having saved the man, as he thought his mother would beat him for not being at school. Later he was given a medal for that act of bravery.

Eddie grew restless, bought an old bicycle and rode the 200 or so miles to London. He lied about his age and enlisted in the military – the elite Coldstream Guards, one of the most prestigious regiments in the British Army. In one of history’s great ironies, he wound up at the Tower of London, guarding the Crown Jewels. Within a short time he had absconded from the military and taken up a new career – as a safe-cracker. He and his gang were successful enough at their new enterprise that Scotland Yard set up a special task force just to track them down.

In 1939 Eddie went to the island of Jersey with his girlfriend, Betty Farmer, intending to go on to France to escape the authorities. Here, the police caught up with him. He was arrested and sentenced to a jail term in Jersey. While he was incarcerated, the Second World War broke out, and Jersey was occupied by the Germans. He offered his services to Nazi Germany as a spy and a traitor, whilst intending all along to become a British double agent. Germany eventually accepted his offer. He was given the name Fritz Graumann (to the Germans Agent Fritzchen) and was trained by the Abwehr (a German spy network) in explosives, radio communications, parachute jumping and other subjects, before being dispatched to England in 1942 to commit acts of sabotage. He immediately surrendered himself to the police before offering his services to British Intelligence, MI5. Thanks to top-secret Ultra intercepts, MI5 had prior knowledge of Agent Fritzchen’s mission, which corresponded in every aspect with the story Eddie told them. Convinced he was genuine in his offer to be a double agent, MI5 decided to use him. MI5 faked a sabotage attack on his target, the de Havilland aircraft factory in Hatfield, Hertfordshire, where the Mosquito bomber was being manufactured.

Now acting for the British as Zigzag – a code name assigned to him by MI5 – he made his way back to his German controllers in occupied France (after being questioned by the Gestapo), and was awarded the Iron Cross for his work as a saboteur. He was then sent to Norway to teach at a German spy school in Oslo. Immediately after D-Day he was sent back to Britain to report on the accuracy of the V–1 weapon, which was just being launched against London. Back in contact with MI5, he passed on information about the Germans that he had gathered at great personal risk in Oslo. He also consistently reported to the Germans that the bombs were overshooting their central London target, when in fact they were regularly landing in the city. The Germans corrected their aim, with the end result that many bombs fell short in the Kent countryside, doing far less damage than they otherwise would have done, and saving a great many lives.

Eddie was reunited with Betty in 1945, and they eventually married in 1947. After the war, Chapman remained friends with Baron von Gröning, his Abwehr handler, who was a thoroughly decent man, and who was later guest of honour at the wedding of Betty and Eddie’s daughter.

Fanny Johnstone of The Guardian newspaper wrote in 2007:

Spies have always been romantic figures, and the idea of having a love affair, or even a marriage, with one, has inspired a host of stories and characters … But these stories rarely tell us much about what it’s really like … a life we assume to be glamorous, and know to be precarious, but which has never been accurately described.1

Perhaps this book goes some way to describe the experience, for the wife of one spy, at least.

1

EDDIE IS DEAD, LONG LIVE EDDIE

The February sun was unusually dazzling as it shone through the French windows of the restaurant, sending up sparkles from the fine crystal and polished silver adorning the elegant tablecloth. Equally dazzling was the blonde woman sitting with three male companions. They had let it be known that they were ‘film people’ and it took no imagination whatsoever to believe that the Harlowesque blonde was the star of some upcoming celluloid epic. The man to whom she devoted most of her attention was film-star material himself – tall, thin, rakishly handsome and with a thin moustache. The two rougher men with them easily could have been mistaken for bodyguards. The woman was Betty Farmer, and they had been in Jersey for a week. This lazy, idyllic Sunday lunchtime in February 1939 was among the best moments of her life. She couldn’t have imagined that she was just a few heartbeats away from the worst.

The handsome man was talking to her about a boat trip that he had seen advertised in the harbour area, but she recalls that her attention was more taken by the small vase of freesias that smelt ‘absolutely heavenly’. At some stage in the conversation, however, she became aware that both the tone and the speed of his speech had changed. Before she knew what was happening, he leapt from his seat, kissed her shoulder and dived through the closed French windows in a shower of broken glass. The man now disappearing through the gardens of the hotel, leaving behind shattered glass, broken crockery, shouting waiters and policemen, and a bewildered and stunned Betty, was Arnold Edward Chapman – professional criminal, safe-breaker extraordinaire, and wanted man. The next time he and Betty would meet, nearly six years later, he would be Arnold Edward Chapman, darling of both the German and British intelligence services, one of the most audacious double agents of all time, and loose cannon. And, grudgingly – to the British Establishment at least – a national hero: Agent Zigzag.

Those few minutes of utter chaos in the restaurant were, unbeknown to Betty Farmer, the pivot point of her life.

Born twenty-two years previously on a small farm near Neen Sollars in Shropshire, Betty was the first of eleven children. If there was a far corner of the Earth in the late 1930s, the farms surrounding this minuscule village in the English midlands were it. The village comprised a few houses, a public house, a church and a school. Betty’s nearest neighbour was a mile away. The farm was surrounded by woodlands and she had to walk to and from her house along a small track a mile or so long, which led to a narrow tarmac road. She walked everywhere, except when the weather was very bad and her father took her in his pony carriage. They would drive some 3 or 4 miles to a main road, and then she walked the rest of the way to school. It was miles away, quite literally, from the bright lights of London and the glittering, glamorous life that awaited her.

As a teenager Betty’s emerging beauty hadn’t gone unnoticed. For a time she went out with the son of the local squire. She was very keen on him but he finally finished the relationship to go out with a more sophisticated girl who had come to the area from London. Betty had a further complication in that the local vicar had fallen in love with her.1 She was going out with him at the same time that she was dating the squire’s son. When that relationship finished she was very upset, but did not want to continue her relationship with the vicar. This caused a local scandal in the village:

People thought I was flighty and as I did not intend to have a serious relationship with the vicar I decided the easiest option was to leave. To be honest, I did not want the responsibility of bringing up my 10 brothers and sisters either, so that was a part of my decision to leave, but not the main reason. So, I decided to go to London.

It is hard to imagine in the twenty-first century how radical such a step was. Even as late as the 1960s it was difficult for a single woman to get a bank account in England without a man’s signature. Dickensian England did not die with Charles Dickens.

Of that time, Betty recalls:

My mother was a very good mother. She worked hard bringing up eleven children with only her mother’s help to aid her. She did all the cooking and baking, and father was always out working, running the farm. They were very upset when I left; they did not want me to leave and I didn’t see my mother and father for a good many years afterwards. But I wanted a fresh start and London was a big city with lots of opportunities. The situation at home with Richard and the vicar was too awkward so I needed to leave. I had a few hundred pounds, which was given to me by my two aunts who lived in Rhyl, and who wanted to help me. I used to go to them when I needed clothes and money and they would help me out. My aunts were on my mother’s side of the family. They spent their life in service working for the same family, who were very wealthy. When the last of the family died they did not have any heirs, so left their estate to my aunts. I had the name of an Irish lady, Wonnie Carey, who ran a bed-and-breakfast boarding house for young ladies in Baron’s Court, west London. I moved in and she took me under her wing.

Wonnie Carey introduced Betty to many people, including Charles Hawtree who owned hotels on the Isle of Man, where she later trained for a year to learn the hotel business.

Because I had been brought up very religiously, I carried on going to church. Wonnie would go to church but she was Catholic. Whenever I’ve been in different countries, whatever the faith, I’ve always gone to church. I used to go with her to the Catholic Church. There were two rules: no trousers, and you had to wear gloves on Sunday.

Betty also adds with a chuckle: ‘no smoking or swearing or any of that either! She was a very religious lady and ran what was referred to at the time as a good clean house. I met a lot of people through her. She was very “correct”.’ Betty chuckles again: ‘I couldn’t have a fellow in. The telephone was in the hallway and if you were expecting a call you hung around in the hallway. There wasn’t much privacy.’

Young, pretty and vivacious, Betty went out from time to time with a man she met at the B&B who took her out to a number of London clubs. It was during this time that she was offered the job of social secretary at a social club on Church Street in Kensington (a wealthy enclave of London) as an evening job. She also worked in a fashion shop during the day. It was at this club that she had her first encounter with Eddie Chapman. One evening as she was playing on the pinball machine a member came in with a new young man. The new man, tall, thin and handsome, stood by the machine having a drink with his friend, and as she moved away, she heard the newcomer say ‘I’m going to marry her.’

‘In a pig’s ear!’ she replied.

Despite her ‘pig’s ear’ remark, she ended up talking with him and having a drink. He said he wanted to see her again. He told her that at that time he was sharing a cottage in Hertfordshire with Terence Young. Young was best known in later years for directing three of the films in the James Bond series, Dr No, From Russia with Love and Thunderball. In his Wikipedia profile, it says: ‘Terence Young WAS James Bond’. There is little doubt that Young fitted the profile of Bond – the erudite, sophisticated ladykiller, dressed in Savile Row suits, always witty, well-versed in wine, and comfortable at home and abroad. It was remarked that Sean Connery, the first Bond, ‘was simply doing a Terence Young impression’. It doesn’t require too much imagination to believe that so, too, was Eddie. Terence was already flirting with the film business by then, so later when Eddie accounted to Betty for his absences as being related to films, it was entirely credible. That he was involved with a criminal gang and out blowing safes would never have entered Betty’s mind.

Despite Betty’s initial resistance, they started going out together. Gradually, a romance developed and, in late 1938, they began living together. Betty continues: ‘In those days, living together was frowned upon by everyone: by one’s parents, by the Church and, if one were in normal employment, by one’s employers.’ As a safebreaker, however, the normal conditions of employment were a little different for Eddie and, even if he had not been handsome and captivatingly charming, she would still have found the excitement of being with him to have been ‘almost unbearable’. It is also worth remembering that Betty still believed that Eddie was ‘in films’, and as such the ‘normal conditions of employment’ didn’t apply there either. At one point, Eddie revealed to Terence that he was, in fact, a crook and blew up safes for a living. Far from being shocked, Terence saw this as adding to the excitement and glamour of their lives.

It was a glamorous time, even though the clubs Eddie took Betty to were on the sleazy side. But as she remarks: ‘they were places of their time’. Eddie himself was a glamorous character, and seemed to know all of the club owners, although why he should was a mystery to Betty. In reality, Eddie moved in the criminal underworld; the clubs he took Betty to were his natural haunts. By the time Betty went to Jersey, she knew this.

Betty takes up the story of the startling events on Jersey, with her and Eddie checked into a hotel as ‘Mr and Mrs Farmer’ of Torquay:

The restaurant at the Hotel de la Plage, right on the waterfront in Havre des Pas, was the place in Jersey to eat. I loved it. Restaurants in London were, at this time, normally more hushed and a little stuffy but here, in Jersey, the atmosphere was alive with a buzz of conversation that belied the awful events unfolding across Europe. The decor was distinctly European, the walls were painted a creamy lemon, the colour of syllabub, the tablecloths were crisp, white linen and the menus were handwritten on sheets of cream vellum. There was a loud woman with a ridiculous hat and a tired fox fur sitting at the table next to ours. She’d talked incessantly since she had sat down but, as she spoke in French and as her clothes were different and more stylish than those I was used to, I really didn’t mind. I was 22 years old and in love with the most handsome and charismatic man I had ever seen and I couldn’t remember ever having been happier.

We had been living together for a little over three months – three months of electric excitement for me and three months of evading the law for Eddie. As I had only recently discovered, in those three months, and for many months before, he and his group of friends had carried out a number of audacious safebreakings in London and things had become more than a little difficult, with an unprecedented amount of interest on the part of the Metropolitan Police – the Met.

In the spring of 1938, the Met set up a special squad to hunt him down. Eddie was far from hiding out – he was out nightclubbing with Betty or travelling down to the seaside resort of Brighton to spend the loot. Nevertheless, he had decided that his run of luck was wearing a bit thin – like all career criminals – so he decided to stop breaking safes for ‘a whole year’. His ‘retirement’ lasted less than six weeks. With a sort of sixth sense that the police were closing in, Eddie decided to make his way to Jersey, and from there on to France.

Betty continues:

In an attempt to lie low for a while and to allow the heat to subside, we had come to Jersey to take advantage of the early spring, and the holiday atmosphere that was so different from the relentless worry and anticipation of pre-war London. Even though I was happy in that moment in the bright sunshine, nonetheless for the last three months I had lain awake in the small hours of countless mornings, wondering how I might continue if Eddie were to be caught and wondering what would become of us if that were to happen. On Jersey, we had a lovely holiday; we danced on the beach and I’d enjoyed Eddie’s wonderful sense of humour.

After Eddie had disappeared through the window, other policemen immediately took charge of Eddie’s two ‘friends’, who had lacked the presence of mind to follow Eddie through the window. Later identified as members of his criminal gang, they were handcuffed and taken away. As normal conversation returned to the restaurant – at least as normal as was possible after the startling events of the past few minutes – Betty sat frozen to the spot. The awful truth was dawning on her that she was a girl not long out of her teens, all alone in what was to all intents and purposes a foreign land. She had very little money, as Eddie always paid for everything, and she had absolutely no idea how to find her way home. That night, alone in her hotel room, she resolved to stay in Jersey until she could find out what had happened to Eddie. The Jersey police had other ideas.

The following morning, her plans were rudely interrupted by a visit from the police, who wanted to know the extent to which she could help them and their Met colleagues from London to piece together the details of a string of robberies. Until now these crimes had defied attempts by a number of police forces to solve them. Betty recalls:

I was taken to the police station and I sat there in abject misery, not knowing what to say and fearing that anything I might say might further incriminate Eddie. Worst of all, it appeared that he might be returned to London to stand trial and I was terrified that all the robberies with which he had been involved, and many others with which he had not, would all be pinned on him in court and that it might be many years before I would see him again. Even though I already knew that Eddie was a criminal and wanted man, I still felt that he had let me down and I was hurt and upset.

Even while Betty sat in the police station, Eddie was still on the run in Jersey. Back in London, a couple of weeks earlier, he had been told that the police were looking for him. ‘A man I knew said that if we could reach Monte Carlo,’ Eddie later remembered, ‘he could get us on a boat for South America.’ He decided he could fly to Jersey, just a few miles off the French coast, and then make his way south to Monte Carlo. He had decided to take Betty with him. Once through the window, and despite being recognised and nearly apprehended by the police, he still believed he had a chance to escape.

After his dramatic exit, he found a place to temporarily hide out in an unoccupied school. He found an old mackintosh to cover his distinctive and colourful clothing – yellow-spotted tie, blue sleeveless pullover, grey flannels, brown sandals and no socks – and eventually made his way to a seedy boarding house, run by a suspicious landlady. He told her he was a marine engineer, but when his picture – to his consternation – was splashed over the front page of the newspaper the next day, the landlady called the police. She reported that her lodger fitted the description of the escaped criminal.

The police told the local populace that caution should be exercised in his apprehension, because he was, they claimed, ‘dangerous’ – despite never having used violence, or even (his specialty was burglary) encountered another person in the course of his ‘activities’. Eddie was away from the boarding house at the time the police were called. Having had the shock of seeing his picture all over the newspapers, he realised the game was up. So, in typical Eddie Chapman style, he decided to go out with a splash. Arriving at a nightclub – presumably after ditching the grubby mackintosh – he ordered champagne. Also in typical Chapman style, he slipped down to the basement and broke into the club’s safe in order to pay for it. Arriving back at the boarding house at 2 a.m., he was immediately arrested, the landlady having phoned the police to report his return.

Betty was all over the papers as well. The Jersey Evening Post reported the next day: ‘She is stated to have denied all knowledge of the alleged activities of her companions.’ Although the Jersey papers were full of the story, they were sympathetic to her plight. The tone of the stories was that she was an unwitting victim of the situation, which was true enough in many respects. She had committed no crime and hadn’t been an accomplice to any crimes. As Eddie had made it perfectly clear to the authorities upon his arrest, Betty knew nothing about his activities or why they were on the island, other than for a holiday. But suddenly she was alone in Jersey, ‘I didn’t know what to do, I was in shock. The people of Jersey rallied around and came to my rescue, collecting enough cash to get me back to London. Eddie was in custody, and there was nothing more I could do’. Eddie was being held in Jersey, and because his last crime was committed in Jersey, he was to be jailed there. Little was she to know that even though he was to be held in St Helier, it would still be nearly six years before they would be together once more.

With Eddie incarcerated and incommunicado, the shocked Betty returned to London to decide what to do next. Still very young, she had no real training or skills, except, inadvertently, evading the law.