9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

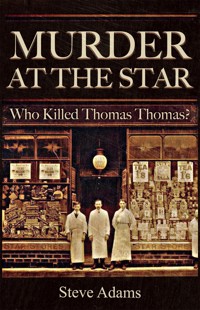

The murder of God-fearing, bible-quoting, partially deaf Thomas Thomas at the branch of Star Stores he managed in Garnant, South Wales has remained an unsolved mystery since it happened in 1921. His body was found on the morning of Sunday February 13th, his head smashed, his throat cut and with a stab wound to the stomach, any of which could have killed him. Over £126 was missing from the store safe, yet there were oddities about the attack which suggested this was more than a robbery that went tragically wrong: Thomas had been gagged with cheese, and there was no tear in his trousers, shirt and waistcoat above the stab wound. What circumstances could explain these things? Garnant was in shock, and Scotland Yard arrived in the form of DI George Nicholls. A number of suspects were identified but none seemed to have the telling combination of motive and opportunity. Despite the expertise of Nicholls the case was eventually abandoned and the killer's secret died with him. Until now. In classic cold case fashion journalist Steve Adams's extensive researches have finally identified the killer, who is revealed at the end of the book, after a thorough reconstruction of the murder and the subsequent investigation. This is the story of a terrible crime in an almost archetypal Welsh mining town. It was a crime symbolic of a turning point in early twentieth century Wales, as the coal industry declined and its recently assembled townships came to terms with their uncertain futures and sought new identities.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 383

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Murder at the Star

Who killed Thomas Thomas?

For Ruth

and in gratitude to Annie Anthony (1923-2006)

and Margaret Deibert (1938-2007) for showing me how

Seren is the book imprint of

Poetry Wales Press Ltd

Nolton Street, Bridgend, Wales

www.serenbooks.com

facebook.com/SerenBooks

Twitter: @SerenBooks

© Steve Adams 2015.

The right of Steve Adams to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

ISBN 978-1-78172-255-8

Mobi 978-1-78172-257-2

Epub 978-1-85411-256-5

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holders.

The publisher works with the financial assistance of the Welsh Books Council

Printed by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow.

Contents

Prelude: The Fat in the Fire

PART ONE

Chapter One: An awful scream and then a thud

Chapter Two: There is a light and the door is open

Chapter Three: You must come at once

Chapter Four: A most harmless man

PART TWO

Chapter Five: The huntsman and the shooting star

Chapter Six: A day like any other

Chapter Seven: A case beyond control

Chapter Eight: He intended to be late

Chapter Nine: When man turns God from his soul

PART THREE

Chapter Ten: A considerable amount of suspicion

Chapter Eleven: Willing and desirous

Chapter Twelve: A good reputation

Chapter Thirteen: Nothing in the nature of a clue

Chapter Fourteen: A very determined blow

Chapter Fifteen: There are no grounds

PART FOUR

Chapter Sixteen: Information Unknown

Chapter Seventeen: Denouement

Chapter Eighteen: Postscript

The Author

Plate Section

“I do not believe less than that the guilty one will eventually be discovered.”

– John Nicholas, Coroner for the County of Carmarthenshire, March 8, 1921

Prelude: The Fat in the Fire

THE AMMAN VALLEY DERBY had become an increasing brutal and bloody affair during its nineteen history, stoked to boiling point by simmering feuds, neighbourly rivalries and bellies filled to bursting with booze and bitter hatred. Meetings between the valley’s two premier rugby sides – Amman United and Ammanford – were a major event. Hundreds of supporters from both communities would flock to witness the spectacle where the anger and frustrations of a working week spent toiling at the coal-face spilled into enmity on and off the field. The contest between the sides on the cold, bright afternoon of Saturday, February 12, in 1921 was no different.

The fixture, the third and final meeting between the sides during the 1920/21 campaign, saw a crowd approaching 2,000 converge on Cwmaman Park on the border of the twin villages of Garnant and Glanaman, whose sportsmen combined to form United. The expectation amid even the most ardent of the visiting faithful was of a comfortable home victory as United looked to capitalise on their superior guile, skill and strength and put one over on the visitors from the small town just along the valley road. Ammanford had risen to become the dominant industrial and commercial power in the valley over the previous few decades and victory over them on the sporting field was a means to bring the swelling egos of its residents crashing down to earth. Nevertheless, a vast crowd made the five-mile journey east in buses, charabancs and on foot to cheer on their warriors in beer-fuelled expectation.

United, or The Amman as they were known, had crushed the visitors underfoot when the two sides met at Cwmaman Park early in the season and the odds were firmly stacked in their favour once again. Ammanford had claimed a most unlikely draw when the rivals had come together on their own patch just a few weeks earlier, but that result was seen as nothing but a blip – a fortunate result on home turf. This latest fixture would restore the natural order and Ammanford and their fans would be sent whimpering back home with tails fixed firmly between their legs.

There was however one chink in Amman’s armour, and it came in the guise of their greatest player. William ‘Billo’ Rees was the valley’s stand-out player of his generation. At outside-half he played the role of lynchpin between Amman’s battling, bruising all-powerful front eight and their speedy, agile backs. Billo Rees was a midfield general – a visionary, fleet of foot and mind, dictating play and controlling possession from the centre of the park. Through him Amman played their game and outscored all-comers. Such was Billo’s prowess with a leather oval ball in his hands that his talent had not gone unnoticed in the higher echelons of the Welsh rugby pyramid. Eventually he would pocket the silver pieces offered by the 13-man game of Rugby League in northern England, but even while still immersed in the union code of South Wales his fame had spread beyond the valley he called home.

On the day Ammanford and their masses rolled up at Cwmaman Park, Billo Rees had been selected to represent Swansea at the highest level of the Welsh amateur game. These were the days – at least officially – before a penny changed hands in the principality for pulling on a jersey on a Saturday afternoon. Though financial reward was not on offer – at least none that any would admit – still the major clubs were able to entice the shining lights from lower down the food-chain, and for smaller clubs like Ammanford and The Amman to see their players linking arms with the best the nation had to offer brought a sense of pride and its own prestige. The talents of men such as Billo Rees put villages like Garnant and Glanaman on the map. Players such as Billo were the source of their community’s notion of self-worth and were heroes to their neighbours. The permit that was requested by Swansea though, was for once not met with favour amongst all The Amman fans, and controversy raged amongst the home support. Some labelled Rees a Judas, claiming he had turned his back on his own and money must surely have changed hands. When Ammanford arrived at Cwmaman Park and their followers filled the Lamb and Flag, the Raven, the Cross Keys, the Salutation, the Prince Albert, the Half Moon, the Plough and Harrow, the Globe and every other pub in Garnant and Glanaman, there was hope. Small hope indeed, but without Billo Rees to orchestrate and marshal their superior forces, The Amman would not be at their best. There was a chance that the visitors might just win the day.

As the drinkers, home and away, their bellies stretched with ale, and whisky on their breath weaved their way through the crisp spring afternoon tempers flared and old rivalries from pub, pithead and pitch stirred amongst the jostling crowds of barging shoulders, pointed elbows and on occasion, flailing fists. Along the way, Police Sergeant Thomas Richards and Constable David Thomas, though lost in the surging crowds making their way to the field, did what they could to uphold order, through mere visible presence more than hands-on policing. As supporters began arriving at the ground they were met by a rumour which soon raged through the crowd like a summer wildfire on the sheep-shorn grasslands of Mynydd y Betws to the south and the Black Mountain to the north. Cheers of joy erupted amongst the home fans while fury raced through the visiting ranks. The word was out that Billo Rees had turned down the call from Swansea and whatever cash might be on offer, and instead had opted to spend that Saturday with The Amman. He had chosen to turn his back on greatness – or at least delay it – to crush the bitterest rivals of his neighbours. To the horror and disgust of many, Rees had rejected the far greater stage to ensure his home side smashed the hearts of Ammanford. It seemed a petty, bitter, spiteful choice. The decision, to travelling fans at least, was a betrayal: a betrayal of the very notion of sportsmanship; a betrayal of the hopes and aspirations of every player on every pitch in every village across South Wales. That The Amman had persuaded their shining light to reject the dreams to which all those who followed the amateur game aspired was beyond redemption. Anger crackled around Cwmaman Park and shoves, sneers and pushes spilled over into punches, kicks and full-blown fights. “The fat was properly in the fire,” reported Sentinel, the Amman Valley Chronicle’s rugby correspondent.

For the players of Ammanford Rugby Football Club, the Billo Rees controversy brought far greater, and more immediate concerns. They knew that whatever the bitter atmosphere amongst the crowds that pressed tight and 30 deep around the touchlines, they would have to face the genius on the field and somehow suppress him. To a man, they all knew without doubt, that Billo’s talent far surpassed their own; his speed of thought, vision and awareness of the field around him would leave them floundering in the mud as The Amman raced out of sight to yet another victory. They knew also that such was his talent they would be lucky to ever find themselves within an arm’s reach of him. The genius that was Billo Rees was simply head and shoulders above them all and far too good for any to ever lay an off-the-ball punch, let alone a legal tackle on him. And so it was that the captain of the Ammanford XV opted for a different approach.

The role of outside-half which Billo had so mastered is the key link in a chain. It is the fundamental position which unites the two disparate sections of a rugby union side. A team is made up of 15 players: numbers one to eight make up the pack while numbers nine to 15 form the back division. The pack are big, strong men who bind together when a scrum is called, who form a receiving line when the ball is returned to play after going off the field. The pack is the blunt instrument, the brutal, pounding hammer designed to wear down the opposition and sap their strength and will. The backs meanwhile spread out across the park. They provide the incisive scalpel cuts to the front-eight’s hammer blows. The role of outside-half – the number ten position – is the pivot between the creaking, groaning brutes of the pack and charging centres, flying wingers and graceful full-backs.

The Amman’s muscular, relentless pack would claim every ball in scrum or ruck and feed it out to the number nine, scrum-half Joe Griffiths. Griffiths’ single purpose on the field was to ensure he offered up clean, unimpeded ball to Rees. Rees meanwhile, would linger ten yards to the rear of the forwards’ melee and from that point of freedom release his rampaging backs to leave Ammanford chasing ghosts. As they tied their bootlaces and pulled on their jerseys, the Ammanford game plan began to take shape. It was a plan so daring, so unpredicted, so unlikely, that none in The Amman’s ranks could have seen it coming. The Ammanford captain ordered his side to ignore the genius Rees and leave him wander how and where he wished. Billo Rees, the most feared and talented rugby player of his generation, was to be given the complete freedom of Cwmaman Park. Instead the entire Ammanford team were to focus their brutal attentions on Griffiths – a talented player in his own right, but far short of the imperious standard of Rees and without the physique and mental ingenuity of his three-quarter line partner. Ammanford would target Griffiths and batter him into the ground. Two, three, often four men at a time would converge on him before he was able even to scoop up the ball up from the back of the scrum. Ammanford would crush him under flying bodies, flailing arms and heavy, studded boots – and in so doing would break the chain at its weakest link.

The tactic sent the home fans apoplectic and yet more fights broke out along the sidelines. The mood both on the field and off turned ugly. Talent, skill and prowess with a ball were all cast to one side. Billo Rees enjoyed barely a touch of the ball all afternoon as Joe Griffiths became a lamb to the visitors’ slaughter. Ammanford claimed a historic and infamous 10-8 victory. The mood along the Amman Valley spat and fizzed throughout the remainder of the afternoon and on into the night. The fat indeed was in the fire.

PART ONE

Chapter One: An awful scream and then a thud

AT 8.15PM ON SATURDAY, February 12, 1921, and with the last customers of the day finally departed, shop manager Thomas Thomas locked the door at the front of the branch of Star Stores in the Carmarthenshire mining village of Garnant. He turned the sign which hung in the window from Open to Closed and pulled down the blind to signal the end of the day’s business. Fifteen-year-old John Morris, one of the shop’s two full-time teenage delivery boys and general assistants, fixed in place the portable gate at the mouth of the porch into which was set the main customer entrance between the two large bay display windows and returned inside via the side doorway accessed down the narrow dark passage between the Star and Mrs Smith’s fruit shop next door. Mr Thomas inspected the board he had fixed over the cracked pane in the window to the left of the store which through his own clumsiness he had broken earlier in the day while attempting rearrange the display. He had cursed himself as the cans had fallen, though not in any way which might offend the Lord. Having assessed the situation following the breakage, he had sent Trevor Morgan, the thirteen-year-old errand boy who worked at the Star on Saturdays, to the cellar at the rear of the store to find a suitable piece of wood with which he had covered the damage and secured the window until a tradesman could be engaged and a more permanent solution arranged on Monday morning.

While Mr Thomas checked the board was fixed firmly in place against the broken pane and would remain secure throughout the night and all day Sunday when the store would remain closed, Phoebe Jones – the first assistant at the Star – and grocery assistant Helena ‘Nellie’ Richards began weighing up the stock as was the custom at the close of business each day. Phoebe had already pulled down the blinds on the grocery counter window and once the board was in place, Mr Thomas did the same behind the provisions counter. The boy Morris and the other full-time general assistant, fourteen-year-old Emlyn Richards, began to clear up after a busy day’s trading, sweeping the floor and tidying away discarded packaging. Both boys were glad of their positions at the Star as it saved them – or at least delayed them – from the otherwise inevitable career of a life spent underground. Emlyn however, was less than overjoyed to spend each day being ordered around by his elder sister Nellie, both at home and at work. With the window finally as secure as was possible under the circumstances, Thomas Thomas went to the safe in the small storage area at the rear of the store which was stacked on top with tins of condensed milk and jars of marmalade, and removed the account books and the two old biscuit tins in which he would place whatever cash was to be kept at the store overnight. Leaving the safe door open, he took both tins and the ledgers back into the shop and, with Nellie having already cleared the surface, placed them on the grocery counter where he began calculating the day’s takings, totalling the cash and receipts, and balancing the customer accounts books. Business has been brisk throughout the day. The big rugby match was of no interest to the shop manager, but the exceptionally large crowd which had swarmed into the little mining village to cheer on the opposing sides in the Amman Valley derby was warmly welcomed. The day had proved particularly profitable for the Star and its manager was greatly pleased by the cash which had kept the tills ringing throughout the afternoon and evening. Thomas Thomas was a man of devout belief. He frowned upon anything other than strict abstinence, but was certainly not averse to taking the money of those men and women who indulged in the demon drink. Indeed, it was better – to the mind of Thomas Thomas at least – that the weak-minded sinners spent their money at the Star rather than in one of the many alehouses that flourished in the valley.

At 8.45pm, Nellie Richards, having sought and received the permission of Mr Thomas, ran a hasty errand for Miss Jones. She raced past the open safe and down the fourteen steps from the storeroom into the cellar where empty boxes and unused odds and ends were stored. Although the cellar had no light of its own, Nellie could see well enough by the light cast down the steps from the shop and she left the Star by the rear basement door. The seventeen-year-old was gone no more than a few minutes, having merely stepped next door to Commerce House, where Miss Jones lodged, to enquire as to the progress of repairs being made to her colleague’s favourite dress. Phoebe Jones had plans for the evening and had already been granted the permission of Mr Thomas to leave work a few minutes early that night. She aimed to finish up her daily tasks as quickly as she was able, race home to Commerce House and change into her best outfit so that she might attend that evening’s concert at Stepney Hall in the company of a close friend.

With Nellie expecting to be gone no more than a minute or two, she left the rear door of the Star ajar. It had remained unlocked throughout the day as usual, with numerous customers leaving the store by the rear entrance. Those who wished to avoid the extra charge for having their goods delivered often came down the steps and selected a box to carry home their purchases and then made their way out by way of the cellar door before turning right and passing along the rear of Mrs Smith’s fruit shop then heading up into Coronation Arcade and back onto the main valley road. Upon her return, Nellie pulled the back door shut and secured it using its two standard sliding bolts. For added security, an iron bar, which was kept behind the door, was positioned across the frame. Nellie’s younger brother, standing at the top of the stairs, paused from his task of sweeping the back room to watch her as she fixed the bar. It was usually his final task of the day. With the door closed and firmly locked, Nellie climbed the fourteen steps from the basement into the room at the rear of the shop and confirmed to Miss Jones that Mrs Jeffreys was progressing well with the stitching repairs and that the dress would be ready to wear in time for arrival back at Commerce House. Only after Nellie had secured the door and returned upstairs did her brother and Trevor Morgan finish their cleaning, sweeping the last of the floors and scooping up their various piles of dirt and detritus from the day into a small box which they then carried down the steps and placed on the floor against the wall between the cellar door and the rear window that looked out down towards the River Amman and the row of houses known as Arcade Terrace. The window was too thickly coated in dust to see through, but in the day-time the light from the sun gave it a warm glow, while after dark the lights from inside the store could be seen clearly from outside. The two boys went back up the steps and Emlyn Richards returned the broom to its usual resting place, leaning against the wall alongside the safe in the storeroom at the top of the stairs. Mr Thomas was meticulous in his approach to the management of the store and the boys knew only too well that the box of floor shavings, the broom and a host of other items were to be placed exactly where expected if they were to escape the shopkeeper’s wrath and yet another sermon from the pages of the Good Book.

At 8.50pm, Nellie Richards and the three boys, with their tasks completed for the day, bade their goodnights to Miss Jones and Mr Thomas and left the shop by the side door behind the provisions counter. Once through the first internal door they walked along the dank, unlit passage and out through the external door which brought them into the night air on the main valley road. The door was supposed to be used exclusively by staff, but they were aware that on a few rare occasions, regular customers arriving after hours had been permitted to enter when in need of some forgotten ingredient necessary for their supper. As Nellie and the boys left they ensured that the door onto the street was pulled shut and the latch engaged. On the main road all was dark save for the lights cast by the shops of Commerce Place. Street-lighting would take another two years to arrive in Cwmaman. The street was growing quiet after the hustle and bustle of the day. The men who had spent the afternoon at the match were in the pubs and would remain there for another hour or two while the women were at home, preparing supper for husbands and sons who had spent the day at the colliery or the tinworks, or those still in the pub. The Richards siblings walked together eastwards towards their home at Garnant Police Station where their father was the village sergeant. The boys Morris and Morgan each went their separate ways to their families.

With the store’s junior staff departed, Thomas Thomas and Phoebe Jones continued settling the day’s accounts and completing the final chores of the weekend. The following day was Sunday, when the only businesses enjoying brisk trade would be the many chapels that lined the South Wales valleys. At 9.45pm, Phoebe finally swapped her work apron for her coat and said goodnight to her manager. Mr Thomas had frowned upon her request to leave a little early – and certainly disapproved of her plans for the evening, however, despite the staunchness of views on the consumption of alcohol, loose attitudes and his adherence to the word of the Good Book, he was a kindly enough man. His permission for her early departure had been accompanied by a short sermon on clean living, but nonetheless it had been granted. As she made her way to the side door, Phoebe paused and looked down from the top the staircase. The February night cast dark shadows in odd shapes around the boxes piled on top of one another in the cellar and into the corners of the darkened room, but there was still sufficient illumination from the shop and storage area gaslights to ensure she could clearly see that the rear door was bolted shut and secured with the iron bar.

As was her habit, she turned back to Mr Thomas to confirm that the rear of the shop was locked up. Her manager, still pouring over the shop ledgers on the grocery counter, expressed his thanks and wished her a pleasant evening. Alongside the account books were the two cash tins. After balancing the tills from the grocery and provisions counters, Thomas Thomas would separate the money into two neat piles, one of Treasury notes and the other of the coins. He would then place the paper money – after it had been bundled into clear amounts – into the smaller of the tins. The silver coins meanwhile would be placed into the larger tin, the coppers returned to the tills to form the float. The smaller tin containing the notes would then be placed inside the larger.

The shopkeeper’s final task of the day – to be carried out just moments before he too swapped apron for jacket and overcoat – would be to place the tins inside the safe for the remainder of the weekend. As Phoebe took one final glance into the storage area she could see that the safe door was wide open, as it would remain until Mr Thomas locked it with the key which had sat in the safe door keyhole all day. Once the safe was locked, the shop manager would place the key in his pocket – along with the key to the side door padlock, which he would fix to the staff entrance once he too had left the building for the night. Phoebe Jones stepped out of the side door and into the Carmarthenshire night at just a minute or two after 9.45pm, the only lights which remained were those burning at the Star and at the fruit shop next door, which would be open for another 30 minutes. Thomas Thomas meanwhile remained behind the grocery counter, struggling to make sense of one small discrepancy in his figures. The miscalculation annoyed him, but not greatly so as he totalled up what had, by any measure, been an excellent day’s trading.

At 10.15pm – some 30 minutes after Phoebe Jones had left the Star Stores for the night, Diana Bowen filled her basket with a few potatoes, a carrot or two, an onion and a few apples from the display boxes in Fanny Smith’s fruit shop at Number Three, Commerce Place. She was the last customer of the day. She would also be the only adult witness to the murder at the Star. Diana paid the few shillings that were due and said her goodnights to Mrs Smith, the proprietor, and shop assistant Alice Stammers before ushering her two young daughters – Catherine and Elsie – to the door. Diana was all too aware that she was already running very late. The 33-year-old would have to hurry if she was to get home in time to have a hot supper ready for her husband David when he arrived home exhausted from another ten-hour shift as a stoker at the nearby Gellyceidrim colliery. Diana pulled her girls out into the street where a fine mist was settling and beginning to thicken. The day had been unseasonably warm, but the temperature had fallen sharply with the arrival of darkness and a hard frost nipped at the children’s faces. The road and muddy fields around the village had already turned rock hard in the cold night and the pavement was turning icy under foot. The main road through the village, which in time would become known as Cwmaman Road but in 1921 was still referred to simply as the valley road, had quietened considerably over the past few hours, but would soon be springing back to life as the men made their way home from the Gellyceidrim, Raven and the other smaller collieries and the tinworks. There were still a few people on the street as Diana and her girls left Mrs Smith’s fruit shop and set off westwards on the short walk towards home. Here and there wives and mothers rushed for late-night provisions to feed tired husbands and sons who soon, like David Bowen, would be heading home from the pit once the end-of-shift hooter blew. Most of the men who had worked the morning shift were still in one of the many village pubs, reliving the agonies of the afternoon’s big derby where Ammanford had caused such outrage by their underhand tactics.

Diana and the girls had taken no more than a few steps along the slippery pavement towards the small rooms they called home at Northampton Buildings when they were halted in their tracks by a most ungodly noise from within Star Supply Stores, the upmarket national chain which occupied Number Two, Commerce Place, next door to Fanny Smith’s fruit shop.

“It was an awful screech,” Diana would later tell a reporter from the Amman Valley Chronicle.

“I was standing on the pavement a few feet away from the window of the stores.

“I heard an awful screech and the sound of boxes being moved about. There was a thud and the sound of running feet – as if someone was running upstairs. The children with me heard the noises as well, and were frightened.”

Elsie, the youngest Bowen girl at nine years, may have been frightened, but she was an inquisitive child by nature and it would require more than just a screech to staunch her curiosity. She rushed to the window and peered inside to discover what had gone on behind the drawn-down blinds of the shop’s frontage.

“She said she had seen nothing inside but tins of condensed milk,” said her mother later. “It would have been about 10.15pm when I heard that dreadful noise. At 10.30pm I was at home preparing supper in our own house.”

However, some three weeks later at the inquest into the death of Mr Thomas Thomas, branch manager at the Star Supply Stores, she put the time of the dreadful shriek more precisely, at exactly 10.20pm.

“It was such an awful scream,” she told Sergeant Thomas Richards the day after the incident as he tried to piece together the murderous events of the previous evening with what limited information was available. Sergeant Richards, the father of Nellie and Emlyn – the two young assistants at the Star – was the highest-ranking officer based at Garnant Police Station. Diana would go on to tell the inquest jury that the scream had startled her and that she thought it strange, but said that she had made no attempt to see beyond the blinds or look inside the shop’s interior. She admitted that she had made no effort to discover the cause of such a fearful scream.

“I was going to have a look,” she said, “but after hearing running on the stairs I thought everything was all right.

“The scream was a loud one, but it gradually died away and then all was calm afterwards. I thought the boy in the shop had had his hand in the bacon-slicing machine, which was on the counter nearest to the side I was standing. I know that he had done it before. Everything was quiet when we left.”

The momentary distraction over, Diana Bowen pulled her girls away and made for home, her mind again now focussed on the return of her husband. Not one other soul in Garnant had heard the awful sound save Diana and her daughters – well none who might ever admit to it. Despite her haste to make for home and begin the task of cooking, Diana did somehow find the time to pause briefly to chat when she saw two neighbours – Mrs Michael and Mrs Walters – making their way towards her on the opposite side of the valley road. Though she was so very late – too late to stop and check on the occupants of the Star – she found time to tell her neighbours of the scare she had just suffered.

“I told them that I had had a fright and that the boy had caught his hand in the bacon machine,” said Diana. “I told them everything was all right now.”

She only stopped once more and then not until she had reached Northampton Buildings where she met Mrs Smith, another neighbour, on the doorstep. Again she put on hold all thought of her husband’s impending arrival to relay her tale of the dreadful noise and the boy with his hand in the bacon slicer one final time. Then, at last, she went inside and set about preparing supper. All was deathly quiet behind the blinds of Star Stores when Diana Bowen and her girls left the arc of light cast from the gas lamps behind the shutters onto the pavement outside the shop. All was quiet behind the blinds of Star Stores at Two Commerce Place in Garnant, because Thomas Thomas, the manager, was already in the grasp of death.

At the very moment that Diana Bowen was regaling Mrs Michael and Mrs Walters with her tale of awful screams and bacon slicers, another Garnant resident was down along the floor of the valley basin some way to the rear of Commerce Place. William Charles Brooks, one of the many men who had arrived in the valley seeking a regular pay packet a decade earlier, was dreaming of his own hot supper after his shift as a beater at the Amman Tinplate Works came to a close. His day’s work over, Brooks had left the tinworks and crossed the Great Western Railway line before making his way along Arcade Terrace, a row of houses in the valley’s dip behind the shops, to his home at Number Four. Brooks, a 32-year-old Londoner by birth, had settled in Garnant around 1910 and married Mary Ann Harries – quite possibly with a shotgun at his head. Baby Henrietta had died before she reached six months – and long before her parents had the opportunity – or the right – to celebrate their first anniversary – but Nelly had soon followed and William junior too.

As Brooks made his way past his mother-in-law’s house at Number Two, Arcade Terrace, he glanced up at the rear of the shops and the dim glow emanating from the properties that lined the valley road which he could see through Coronation Arcade. The Arcade, which in turn had given his own terraced row its name, ran at ground level between Numbers Four and Five, Commerce Place. Number Four was the second of the two drapers shops in the row belonging to Williams and Harries – the partnership between two former valley rivals had benefitted both and their booming business had seen them occupy Numbers One and Four, sandwiching Star Stores and Fanny Smith’s fruit shop in the block. Both drapers shops were in darkness but Brooks could see lights still burning upstairs in the fruit shop and at the rear of the Star.

As he looked he saw a figure lurking in the shadows of the Arcade. It made no move towards the street, but stayed half hidden within the folds of darkness as if watching and listening. From the valley road he was all but invisible, but Brooks was able to make him out. The man appeared to be waiting for any sound or movement that might be made out on the main highway beyond William Brooks’ sight or hearing. The shadows cast by the shop-lights which ensured his invisibility from the road only served to enhance the definition of his form from Brooks’ lowly point of observation in the valley basin. The man, Brooks realised, was Morgan Walter Jeffreys, the landlord of Commerce Place, the man who had built the row of shops from nothing, and who revelled in the position such importance granted him. Eventually the figure turned and, facing Brooks though clearly unaware of his presence, made his way down to the end of the Arcade before turning left, following the line of the buildings along back of the drapers, fruit shop and the Star to Commerce House, the residential property set behind the first of the Williams and Harries shops.

Sometime after 10pm, but certainly before 10.30pm, Anne Jeffreys opened the rear door of Commerce House and sent Spot the family dog outside to go about his nightly business. The rear of Commerce Place was quiet and Mrs Jeffreys neither saw nor heard anything she might consider untoward. She went back inside and left Spot in privacy. Within minutes however, her quiet peace was shattered as the dog roused her from her chair beside the fire.

“Spot barked furiously,” Mrs Jeffreys told Sergeant Richards the following day.

“As everything was so quiet outside I shouted to the dog: ‘What’s the matter boy?’”

The 61-year-old was all alone in the house, but was not one to be shaken easily. Although it was her husband who had overseen construction and who managed the current tenants of Commerce Place, it was Anne who entered into discussions with Lord Dynevor over a lease for the land. It was Anne who, on July 13, 1895, finally reached agreement with the land-owner, and signed the lease for the vacant plot from which would one day spring what she had every hope might become a retail empire. The lease remained in Anne’s name until she signed it over to her husband on August 29, 1903. However, it was Anne who would remain the named defendant in a twenty year legal dispute with the Dynevor Estate. The wrangle – over financial responsibility for the costs incurred by the essential improvements required on the valley road – saw Anne and her husband refuse to pay a single penny of the agreed ground-rent until ordered to do so by a High Court ruling following a bitter battle with Walter FitzUryan Rice, the seventh Baron Dynevor, in July 1915. The legal costs alone had, in truth, all but bankrupted the Jeffreys. Anne however had refused to be intimidated by the Baron’s lawyers and friends in the judiciary. She was certainly not a woman afraid of the dark. She went to the door to see what had so riled the dog, but saw nothing she considered to be obviously out of the ordinary.

“I could see nothing so I called the dog to come in,” she said. “Spot then came in, so I forgot everything about it.”

At precisely 10.30pm, Fanny Smith and Alice Stammers, having dealt with the few last late-comers, locked the front door of the fruit shop at Number Three, Commerce Place, and pulled down the shutters on the windows. With business finally over for the day the two women went upstairs to their living quarters and settled down to supper. They would – as usual – return to the shop later to clear away the rubbish of the day. Like so many of the residents of Garnant, neither Fanny nor Alice was a native. Fanny Mansfield had been born in Bath in 1869 and at the age of twenty-five was swept of her feet by a smooth-talking travelling fruit salesman from Wolverhampton by the name of William Henry Smith. They married in the summer of 1894 and in little over a year, a son – Raymond – was born. All was not well with their new-born however and Raymond was classed as “paralysed at birth” – quite possibly a Victorian diagnosis for cerebral palsy. For a time at least – and quite possibly because of Raymond’s condition – the Smith family settled in Bristol. William continued his life as a commercial travelling salesman while Fanny remained at home with Raymond and Phillip, the family’s latest addition. Phillip had arrived in the early months of 1901 and would be the Smith’s only other child. The family had however also gained another – albeit unofficial – member by the time Phillip had been born. The couple had taken on a general maid to help relieve the pressure on Fanny while William was “on the road”. Alice Stammers was a Londoner, born in 1878, and by 1901 was already a fixture in the Smith household. She would remain at Fanny’s side for half a century until the death of her employer in 1950, but her devotion would go unrewarded and unrecognised. She received not one penny of the £2,400 nest egg Fanny Smith had accumulated prior to her death.

By 1911, William too had tired of the life of a travelling salesman and, with Fanny, Phillip and Alice joining him, had set up in business running a fruit shop in Sale, Cheshire. Raymond meanwhile had been placed in the care of a residential school for epileptic children close by at Nether Alderley. Life in the north of England did not go especially well for the Smiths however and by the middle of the decade they had returned to Bristol, where Raymond died aged 23 in the latter months of 1918. Soon after the death of their eldest son, the Smith family moved again, taking up the tenancy of a vacant shop in the village of Garnant. Alice would help out in the shop as well as with the household’s domestic chores. William returned to the life he knew best – on the road as a travelling salesman and fruit wholesaler.

Each night, with the day’s work done, the two women would lock the shop at 10.30pm and go upstairs where they would for a short time settle down to eat their main meal of the day in a room at the rear of the first floor of Number Three, Commerce Place. The room overlooked the rear gardens of the row and down towards Arcade Terrace. Further still, on a clear night, they could see across the GWR railway line, to where the lights still burned at the Amman Tin Works. Beyond them, in the inky blankness past the sight of Fanny Smith and Alice, rolled the River Amman. As the two women ate their meal on the night of February 12, 1921, they heard not a sound nor saw any movement whatsoever at the rear of Commerce Place. They heard no barking dogs, no shouts, no awful screams, nor any music in the night, and they most certainly did not see a killer making his escape from the rear of the building next door. At 12.45am, Fanny Smith and Alice Stammers could put off their final chores no more. The two women returned downstairs to the fruit shop and cleared up the empty boxes, the wrapping paper and the leaves and vegetation left over from the day’s trading. Both noticed however that despite the lateness of the hour and the arrival of the Sabbath, the lights within Star Stores still burned brightly.

Thomas Walter Jeffreys had clocked off work at Cawdor Colliery at 10pm after another arduous eight-hour shift at the coal-face and begun to make the slow trudge home. By the time he reached Commerce House, passing to the rear of Fanny Smith’s fruit shop, Harries and Williams drapers and the cellar door of Star Stores, it was as close to 10.30pm as made no difference. Thomas, at 26, was the youngest – and more respectable – son of Morgan and Anne Jeffreys, landlords of Commerce Place. When interviewed by the Amman Valley Chronicle in the days after the murder at the Star, Thomas claimed he had noticed nothing out of the ordinary on his way home that night. Perhaps he was too tired or too hungry; perhaps it was because of the heavy mist that was thickening and settling in the valley by the time he got home that evening, but for whatever reason he said that he had not spotted the lights still burning at Star Stores.

“I noticed nothing then but that the back door was closed,” he told the newspaper’s reporter. The only thing he thought he had noticed was in fact wrong. However, when interviewed by police in the days that followed, his recollection of the evening proved somewhat different.

“I noticed a light on in the Star Stores as I was passing through the back,” he told Sergeant Richards. He was in no doubt that he had noticed it as he had gone so far as to comment on the shopkeeper’s long hours on his arrival home.

Once inside Commerce House, Thomas settled down in the kitchen to eat the supper prepared for him by his mother. There he said he remained until Phoebe Jones, the first assistant at Star Stores, arrived home at her lodgings from the concert at Stepney Hall a little after 11pm. Phoebe certainly had noticed that the lights were still burning and praised – though possibly with a snort of derision – the dedication of her manager, who she assumed was still struggling to pinpoint the minor discrepancy in his accounts. At around 11.30pm, Thomas and his father set out across the fields to the stables which they kept nearby to “bed the ponies for the night”. As they made their way back to Commerce House they again noted that the lights were still burning throughout the store, but saw no reason for alarm. By the time father and son had arrived back home, Phoebe was nowhere to be seen. Mrs Jeffreys told them she had gone to check on Mr Thomas at the Star, though she can have been gone for no more than a few minutes. Morgan Jeffreys went to bed while Thomas settled back into his seat alongside his mother.