Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

As a young girl toiling in a South Wales tin works, Dorothy Squires dreamt of being a singing star, but was ridiculed by all around her. At the tender age of sixteen she escaped the valleys and boarded a train for London. It was here that she met and fell in love with songwriter and band leader Billy Reid, the older man who was to make her a star. The pair became an international success, but the relationship foundered, and Dorothy found herself falling in love with the much younger Roger Moore, a struggling actor who she would spend all her time establishing as a star. Written by Dorothy's good friend Jonny Tudor, this fascinating first biography of a Welsh singing phenomenon is an unprecedented insight into the glitz and glamour of 1940s and '50s Hollywood and Dorothy's triumphant comeback in the 1960s and '70s.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 358

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

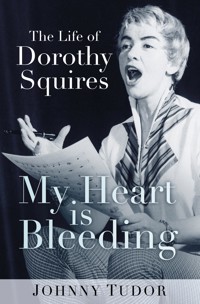

Cover illustration: Film star Roger Moore plays the piano for his wife, singer Dorothy Squires. (John Pratt/Keystone Features/Getty Images)

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Johnny Tudor, 2017

The right of Johnny Tudor to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8292 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

1 The First Meeting

2 The Early Years

3 The Composer and the Voice

4 The Roger Years

5 A Solo Career

6 Other Suitors

7 The Comeback

8 President Records

9 The Bill for the First Concert

10 The Tour

11 The Payola Scandal

12 The House at Bray

13 Australia

14 Dorothy’s Book

15 Horses

16 The Final Downfall

17 Homeless

18 Back to Wales

19 The Recording

20 The Funeral

Epilogue

Foreword

After the success of Say It With Flowers, the play I wrote about Dorothy Squires with my good friend Meic Povey, many people have expressed a wish to know more about this talented, controversial and sometimes difficult Welsh woman. Having the advantage of knowing Dorothy for most of my life and the benefit of access to her personal letters and reminiscences given to me by her niece, Emily Squires, has given me a first-hand and sometimes emotional insight into her story that allowed me to open up untold layers of this dramatic life. I was also privileged to have recorded interviews with Dorothy just before she died. Consequently, her quotes give this book an authenticity, which I would not have been able to achieve had it not been for the 5 hours of recorded dialogue in my possession.

My life has been inextricably linked with Dorothy’s and although I feature quite heavily in this book, it’s not my story; it’s Dorothy’s story seen through my eyes. At times it reads like a Greek tragedy – her relentless journey from rags to riches and back again seems at times to be like a ridiculous parody – but there are great moments of joy and humour too. So, as you turn the pages of this book, I hope my efforts bring to life the excitement of the good times when Dorothy was riding high, as well as the trials and tribulations of her journey from humble beginnings in the South Wales Valleys to the pinnacle of international stardom. It was a privilege to be with Dorothy at the end and, although the manner of her passing was sad, I will always remember her as the vibrant woman she once was, how I learnt from her and how she touched all our lives back then.

Acknowledgements

This book would never have been written without the encouragement and friendship of the television producer Peter Edwards, who had the vision and confidence in my ability to write it and my friend Emily Squires, who gave me access to Dot’s personal letters and reminiscences and trusted me to portray her aunt’s life accurately and honestly. I am most grateful to them and the people who gave up their time to relay their memories of Dorothy to me. In particular Dorothy’s friend and musical director Ernie Dunstal; John Lloyd, her publicist and loyal fan, who is sadly no longer with us; Hilda Brown her secretary and Peter Bennett a stalwart friend and confidant, who with his partner Des Brown were there for her when she needed it most.

1

The First Meeting

LONDON 1961

See Him Rog? I knew him when I had big tits and straw in my hair.

These were the first words I ever heard Dorothy Squires utter. She was walking down Wardour Street in the West End with her then husband Roger Moore and her recording manager Norman Newell, when she spotted my father and me. ‘My lovely Bert,’ she squealed. Then, totally ignoring Roger, gave my father a smacker of a wet kiss. I was an 18-year-old stage-struck kid in London for an audition that day so you can imagine how blown away I was, not only by Dorothy’s mesmerising personality but by meeting The Saint himself. This was pre-Bond but Roger was already a big star.

Dorothy and Roger were on their way to a private showing of a film called Tammy Tell Me True, starring Sandra Dee and John Gavin. Dorothy had written the theme tune for it and she was on a terrific high. So, still ignoring Roger, she invited … no, demanded that we go with her to the champagne reception. After too much champagne and the 2-hour film, we emerged blinkingly and half-cut into the harsh daylight of the street. A bunch of young girls immediately surrounded Roger pleading for his autograph. We walked on with Dorothy who pretended not to notice the gaggle of giggling girls then, turning to Roger, she yelled ‘come on you prick we’ll be late.’ I was to realise later that her total indifference to Roger’s star status was because their marriage was on the rocks. Roger, ever the gentleman, graciously extricated himself from his adoring fans and joined us but it was obvious things weren’t right – not long after that their much publicised break-up hit the press. Putting on a brave face, Dorothy linked arms with my father and me and announced in a commanding voice that we were all going to Raymond’s Revue Bar – she’d booked a table to celebrate. So, with Dorothy taking the lead, we made our way to Soho. I’d never seen a place like it. Its intoxicating atmosphere engulfed me.

Soho pulsed with life in those days. Flashing neon signs advertised adult entertainment: strip clubs, massage parlours, adult bookshops and the like. Touts were standing in doorways of sleazy clubs. ‘Come inside, they are naked and they move,’ they bawled to anyone within earshot. Situated adjacent to these clubs was one of the more respectable if not entirely innocent venues in Soho, the Windmill Theatre, where comedians battled valiantly to get laughs from jaded mainly male audiences in grubby raincoats. The only time the comics would raise a titter – if you’ll excuse the expression – was when the men, having sat through all five shows to ogle the girls, would see one of the artists going wrong. An alternative source of entertainment was when someone would vacate a front row seat and a stampede would ensue to claim it; men would clamber over the backs of seats to get a better view of the naked girls standing motionless in tableaus. Outside the stage door chorus boys lounged, still with their make-up on, having a well-earned fag – the tobacco variety of course.

Opposite, in Archer Street, stood a group of musicians on the short stretch of pavement between Great Windmill Street and Rupert Street. I asked Dorothy what they were doing. She told me that they were collecting their pay. ‘As long as I can remember,’ she said, ‘musicians have gathered on Mondays to collect their fee from previous gigs and see if there was any work for the coming week. It was like a club; they meet to share stories about gigs, club owners, and just generally shoot the breeze.’ Dorothy knew all this stuff because she’d started out as a band singer when she was a kid; in her words she was one of the boys and often preferred to travel on the band bus with the musicians than travel in her own car.

Across the road from Archer Street was our destination; a huge red neon sign flashed announcing Raymond’s Revue Bar. The club was the creation of property magnate and magazine publisher Paul Raymond for whom some years later I worked in another of his venues – the Celebrity Restaurant. It was at the Celebrity that Dorothy met and fell for another of her beaus Keith Miller but more of that later. The Revue Bar offered traditional burlesque-style entertainment, which included strip tease. It was popular with leading entertainment figures of the day and was one of the few legal venues in London to show full-frontal nudity by turning itself into a members-only club. I asked Dot if she was a member. She said she didn’t need to be; her face was her membership. So, ignoring the doorman she made a grand entrance with the rest of us trailing in her wake.

We were shown to our table. More champagne was ordered and Dorothy proceeded to regale us of how writing the theme for the film we’d just seen had all come about. While she was in Hollywood, she’d heard that Ross Hunter, the Oscar-nominated director of Airport and Pillow Talk had been looking for a theme for his picture so she set about writing it. When she’d finished she sent Roger over to Universal International with the manuscript and hoped for the best. There were two songs shortlisted and Dorothy’s was one of them. At five o’clock that day she received a call from the studio to say her theme had been chosen; it was in the picture. Dorothy was ecstatic and recalled:

And you imagine what I was like? There were seven workmen in the house, I got them all drunk. I used the Vintage champagne, Roger nearly killed me. They [the workmen] didn’t know what it was all about. The next day there I was, eight o’clock in the morning on the sound stage of Universal International in a headscarf and slacks listening to a sixty-piece orchestra conducted by Percy Faith. They were playing my tune. It was one of the biggest thrills of my life and the icing on the cake was the $2,000 in advance of royalties I was paid.

Dorothy, like most Celts, was a good storyteller so, as we quaffed more of her champagne, she proceeded to entertain us with more tales of Hollywood. Roger had of course heard it all before but this didn’t deter her; she was the centre of attention now and loving it. In England she was Dorothy Squires not, in her words, ‘Mrs Roger Bloody Moore’. I was too young to realise what she meant by that remark but in retrospect I think she resented the fact that her star status had been eclipsed by her handsome and much younger husband.

I only met Roger that one time and I was a little overawed by being in the presence of a superstar. Remember, I was this young gauche kid with theatrical aspirations carrying a portfolio of publicity photos but Roger had a great way of making one feel at ease in his presence. Dorothy insisted he take a look at my pictures and he picked one out of me doing an impression of Sammy Davis Jnr. Later, when he was thumbing through a magazine he found a picture of Sammy and quipped, ‘Hey John, there’s a bloke here taking the piss out of you.’

That first encounter was the beginning of a lifelong and sometimes difficult friendship with Dorothy. It’s funny how some people’s lives get intrinsically linked with someone else; I seemed to have been linked with Dorothy all my adult life, from that first meeting in London until her sad demise in April 1998 at Llwynypia Hospital.

Dorothy was a paradoxical character – a mixture of Auntie Mame and Cruella de Vil – when she was on form there was no better company; I have fond memories of her entertaining us with her colourful stories of Hollywood and all the film stars she knew. But Dot had a dark side; she could fly off the handle at the least provocation and reduce you to tears with one of her vitriolic jibes. On the other hand she was generous and kind; her impressive mansion in Bexley was an open house to any lame duck that needed a bed for the night. She wasn’t a very good judge of character though and was often taken for granted by all the sycophantic hangers-on hoping to be the next Roger Moore.

While I was appearing at the Pigalle, a nightclub in London’s West End, Dot insisted I stay with her at St Mary’s Mount, her grand house in Bexley, and The Mount became my home whenever I was in London. I couldn’t believe my luck; I was only on fifty quid a week and I was living in a twenty-two-roomed mansion with a swimming pool. One night during the performance at the Pigalle a message came backstage that Dorothy was out front with the producer of the show, Robert Nesbit. She wanted me to join them. It’s an unwritten rule of the theatre that you never go out front during a performance but Dorothy assured me that she’d cleared it with the management and so out I went. It turned out to be a very embarrassing experience; Dot had had a drink or two that night and was being a bit discourteous towards Mr Nesbitt: ‘Do you remember when you fucked up the lighting for a show in Las Vegas, Robert? No wonder they call you the Prince of fucking Darkness!’

I didn’t know where to put myself, this was my boss she was insulting and a very important man in show business; he was the producer of the Royal Command Performance for goodness sake! I needn’t have worried though; Robert just laughed and said ‘you’re incorrigible Dorothy’. Robert Nesbit was a gent. After a six-month run at the Pigalle I went into a musical called Cindy at the Fortune Theatre in Covent Garden. The assistant stage manager was a young fella called Cameron Mackintosh – I wonder what happened to him! Dorothy insisted on coming to the opening night but I didn’t really want her to come; I knew how outspoken she was and I was worried in case she would upset someone. She sat in the circle with my father and when I did my big number she started yelling encore at the top of her voice and whistling. This was the second time she’d embarrassed me but this time it had a positive effect; the audience picked up on it and I got a standing ovation. Inadvertently she’d done me a favour and we drove back to St Mary’s Mount to celebrate.

St Mary’s Mount – Bexley

I have some great memories of that large Victorian pile set in 4 acres with its lawns sweeping down to the swimming pool and orchards beyond. I lived in a council flat with my parents in Port Talbot at the time so this palatial mansion with its Gone With The Wind staircase, nine bedrooms, oak-lined dining room, snooker room, bar as big as any pub, library and huge ranch-style lounge was a magical place to me. Dorothy had added the Ranch-style room to this already enormous house without planning permission. Dorothy never asked permission to do anything. When she had to fill her swimming pool she just put a hosepipe in it and let it run for weeks. She should have called the fire brigade and paid them to fill it, after all it took 33,000 gallons but she continued to do this until the Water Board, who thought there was a leak, turned up and threatened to take action.

The house was always full of people. There were never less than ten for Sunday lunch. Dorothy would also throw parties for the world and his wife, where one would rub shoulders with the great and the good of show business: Shirley Bassey, Diana Dors, Tony Hatch, Jackie Trent, Peggy Mount, Lionel Bart et al. I remember being taken aback by how posh William Bramble was and not a bit like his character in the situation comedy Steptoe and Son, save for how his ill-fitting false teeth would drop when he spoke, reminiscent of Old Man Steptoe himself.

Another real character that stayed with Dorothy was Rex Jameson, who was often on Dorothy’s variety bills. His alter ego was Mrs Shufflewick or Shuff, as he was affectionately known. The character he portrayed on stage was an old cockney woman in the snug of her local pub called The Cock & Comfort: ‘A lot of comfort, but not much of anything else,’ he would quip. Shuff had a bit of a drink problem. When Dot paid him on a Friday he would post himself some money to the next theatre so he wouldn’t spend it all on booze. When he would turn up at Bexley he’d go straight to the bar and drink a bottle of sherry straight down and Dorothy would have to put him on the train for home blind drunk. Shuff was always grateful for Dot’s kindness and would invariably leave a present as a thank you for her hospitality. Little did she know at the time that Shuff had nicked it from the Army and Navy Stores.

Dorothy’s parties were wild affairs; if not exactly Valley of the Dolls, they weren’t mother’s union soirées either. You never knew where you would be sleeping or with whom. When all the beds were full, people could be seen fornicating al fresco in the flora and fauna.

When things got a little too wild, which was often, I would make my excuses to Dot and sojourn to the office. I slept in the office most times. One night I was aware of a vertically challenged refugee from Snow White who was a little worse for wear. He staggered into the office mumbling that he couldn’t find the toilet. I pointed him towards the door but he opened the wrong one and fell down the cellar. I expect the next pantomime performance was Snow White and the Six Dwarfs. Everyone who went to Dot’s parties had to do a turn and Emily Squires, Dorothy’s niece, remembers:

Dorothy had set up a microphone in the white room and the guests were taking it in turns to sing. Dorothy sang first followed by Shirley Bassey then Diana Dors. I was only a teenager but I remember feeling sorry for Diana, having to follow two of the most powerful singers in show business; she should have gone on first. During the impromptu karaoke session Lionel Bart sat with Shirley Bassey’s first husband, Kenneth Hume, and I remember thinking that it was strange him wearing make-up and in the day time too.

Dorothy asked Jacky Trent to get up to sing but she declined saying she had a bad throat. Dorothy, not one to mince her words, told her she’d never be a singer as long as she had a hole up her arse then turning to me said ‘give us a song John,’ and had the cheek to ask Jacky’s husband Tony Hatch, the record producer and songwriter, to accompany me on the piano.

At another party I was sat next to a skinny, morose looking man with a black curly perm wearing sunglasses. I asked Dot who the strange looking guy was. She told me it was Phil Spector the famous, or by now the infamous, murderous music mogul and record producer of the Wall of Sound fame – Dot knew everybody. Well … I say she knew everybody; one guy called Eddie would turn up with his case and move in for a few days, do a bit of work around the house and then leave. Nobody seemed to know who the hell he was; he was just Eddie. Another uninvited guest to St Mary’s Mount was a ghost – Dot swore the house was haunted; she even got a priest in to exorcise the place. Lights would go on and off for no apparent reason and Dot’s sister, Rene, swore she felt little feet running over her when she was in bed. Dorothy swore it was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who was rumoured to have lived there – but I think it was Eddie!

I saw so many famous people pass through Dot’s house: Tony Hancock, the biggest TV and radio star of the fifties and sixties, escaped from a drying out clinic in Brighton and turned up at St Mary’s Mount seeking sanctuary; he was accompanied by the wife of John Le Mesurier (Sergeant Wilson of Dad’s Army fame) with whom it transpired, he’d been having an affair.

Tony was in a terrible state; he had the DTs and his body was covered with scabs. Dorothy, taking pity on him, told him he could stay until he could sort himself out and made up a bed in the library – big mistake – he drank a bottle of scotch and half a bottle of gin that had been inadvertently left there. The next morning Dot was awoken by the apparition of a naked Tony Hancock, hovering next to her bed, his ample appendage dangling far too close for comfort in front of her eyes. The unshockable Dorothy, flicking the mammoth member away said ‘get that out of my face’ and accepted the tea he was offering with grace. Then, seeing the humour in the situation, quipped ‘Who’s your tailor?’ The next day Dorothy took a phone call from John Le Mesurier. Tearfully he explained that he’d heard through the grapevine that his wife was at St Mary’s Mount with Hancock and what should he do about it. ‘Why are you asking me?’ she said, ‘I’ve really fucked up my life good and proper.’ Then as an afterthought, told him to put a new song in his act, and put the phone down.

Later, Dorothy received a phone call from Billy Marsh, Tony’s agent. He’d also heard that Tony was at Dorothy’s and pleaded with her to keep him sober as he had an egg advert to do. She promised to do her best. She hid all the booze in her bar and plied him with coffee. When Tony’s car came for him it was a beautiful navy blue drophead Rolls-Royce. Dorothy told Tony’s driver that ‘Mr Hancock has got an egg commercial to do, which will earn him a lot of money. So don’t stop on the way to give him a drink.’ But Dorothy hadn’t accounted for the deviousness of a confirmed alcoholic. Tony bribed his chauffeur to smuggle in a half bottle of brandy and he drank it all before leaving for the studio. Dorothy called Billy and said ‘you’ve had it, Billy, you’ll have no commercial today’. Billy must have succeeded though, because Tony was to be seen ‘going to work on an egg’ and demanding ‘Where are my soldiers?’ on national television for the rest of the year.

Another time I stayed with Dorothy was when I was appearing at the Beaverwood Club, a stone’s throw away from Bexley. I asked Dot if she would like to come one night and she told me that she was banned. It transpired that on Christmas Eve in 1965 Dorothy and Emily had gone to the club. Dot was accompanied by Tom Jones and Emily was accompanied by Viv Richards, a long-haired member of a pop group called the Pretty Things. Emily remembers Dorothy and Tom getting a bit too amorous – I wonder if he’s put that in his book. They were being particularly loud and disruptive that night, which brought stares from the surrounding patrons and they were respectfully asked to leave.

Emily Squires was a regular visitor to Bexley. When her father (Dot’s brother Fred) died, Emily’s mother, Joyce Golding, a variety artist, was on tour with Max Miller so Emily was put into a convent at the tender age of 5. She told me the day her mother handed her over to the Reverend Mother she felt abandoned, alone and afraid. She very rarely saw Joyce and, except for the odd comic book she would receive through the post, there was very little contact. Dorothy became a sort of surrogate mother to her; in fact most people thought Dorothy was her mother.

She loved Emily like the daughter she never had, even offering to adopt her and every chance she got she would take her out of the convent and bring her back to Bexley. Emily, like me, thought St Mary’s Mount was a magical place and a wonderful place to grow up. As a child she would dress up in all of Dorothy’s pantomime clothes that were kept in huge wardrobe skips under the stairs, play in the woods with her friend Carl and swim in the pool. She recalled with love the way she would sit in the empty pool as it was being filled and rise to the top with the water.

One memorable event Emily recalls is when Dorothy and Roger turned up at Our Ladies’ Convent to watch her singing in a school concert. They arrived in their powder blue Ford Thunderbird convertible; Dorothy dressed in a mink coat and diamante glasses and Roger in his Saville Row suit. They stuck out like sore thumbs amongst the other parents. Dorothy proceeded to make a spectacle of herself as usual. She was like Rosalind Russell in Gypsy giving instructions to Emily from the audience but instead of yelling out ‘sing out Louise’, she was yelling, ‘Sing out Emily Jane’, much to Emily’s embarrassment. To make amends she invited four nuns and six kids to Bexley for the day. It was a lovely day; the pool had just been filled and Roger was dispatched to get ice cream for everyone. The kids, not having swimming costumes with them, raided Dorothy’s knicker drawer and jumped squealing with delight into the water clad in an assortment of Dorothy’s multicoloured knickers.

Emily told me that her relationship with Dorothy was idyllic whilst she was a child but as soon as she reached puberty Dorothy treated her more like a companion than a teenager. She took her to places that in many people’s eyes were not suitable for a girl of such tender years who’d been brought up in a convent. Dorothy even took the unsuspecting Emily to see an X-rated movie at the Windmill because an actor Dot had been out with was in it and she’d heard there was a great shot of his bum.

Emily, having been exposed to the world of showbiz from a young age, had grown up fast. When she was only 8, she’d inadvertently whistled in the dressing room, a heinous crime amongst the theatrical fraternity. Like most people in showbiz, Dorothy always adhered to the superstitions of the theatre and ordered Emily to go outside, turn round three times, swear then come back in. When Emily protested that she didn’t know any swear words, Dot told her to try bollocks.

Emily often went with Dorothy to Denmark Street, the little street off Tottenham Court Road affectionately known as Tin Pan Alley. It was the hub of the music business in those days, frequented by recording managers, songwriters, pop groups and song pluggers. There was a real buzz about the place with its music shops and small recording studios, where hopefuls could make an acetate disc of their latest song and try to sell it to one of the publishers. Wannabes would hang out in a coffee bar called La Giaconda hoping to be discovered. Everybody congregated in that little coffee bar or The White Lion pub at the other end of the street and it was here that Emily met and fell for a young rock drummer. This became a bone of contention between Dot and Em; Dorothy didn’t like the fact that he was married, which was rich coming from her; she’d lived with a married man for twelve years before meeting Roger, with whom she started having an affair whilst he was still married to his first wife.

Emily could give as good as she got though, and was probably the only one who would tell Dorothy the truth and not what she wanted to hear. This often led to heated screaming matches, which sometimes became violent, leading to Emily walking out. One particularly pernicious punch-up occurred in The White Lion. Emily was having dinner with Dorothy when, after a few glasses of wine, Dorothy started insulting Emily’s boyfriend by calling him ‘An ignorant cockney cunt’. Emily retaliated, telling her not to call her boyfriend a cunt. Dorothy, mishearing the comment, thought Emily had called her a cunt and war broke out. She took a swing at Emily and caught her hairpiece, which went flying and landed in some bloke’s Boef Bourguignon. Emily made a dash for the ladies’ followed hot foot by Dorothy. With flailing fists, she set about her cowering niece; her diamond encrusted ring cutting Emily’s face. Emily, being twice the size of her diminutive aunt pinned her against the wall and started shouting for help. Two music publishers, hearing the rumpus, rushed into the ladies’, grabbed Dot before she could do any more damage and Emily escaped, with Dot yelling, ‘Fuck off, I’ve been looking at my brother’s face for too long,’ ringing in her ears. Make of that outburst what you will. To me, it was as if Emily reminded Dorothy of her brother Fred, who also wouldn’t take any shit from her. Fred was 6ft 2in but this didn’t deter Dorothy from standing on a chair to hit him on the head with her stiletto-heeled shoe yelling, ‘Take that, Captain cunt’.

Dorothy didn’t see Emily for months after the incident in The White Lion. She tried calling her every day, leaving messages but Emily wasn’t returning her calls. Dorothy was always sorry after her outbursts and would try anything to make amends. So, in desperation she wrote her a letter, which read:

The wall flowers miss you, the dog misses you, the cat misses you, the washing machine misses you; in fact, we all fucking miss you.

After every bust-up, which were legion, Emily would inevitably be drawn back to St Mary’s Mount by Dorothy’s Svengali-like magnetism and everything would seemingly go back to normal – if you can call living with Dorothy normal. And so, Emily resumed her role as companion, accompanying Dorothy on her trips to her favourite haunts, one of them being the A&R Club, which was situated on top of Francis, Day and Hunter, the music publishers in Tottenham Court Road. It had a colourful clientele, being the preferred watering hole for some of London’s prime villains, madams, musicians and singers from Tin Pan Alley and actors like Kenneth Williams and Ronnie Frazer. The club was owned by stage and TV star Barbara Windsor’s first husband, the infamous Ronnie Knight, who was rumoured to have been linked to the gangland slaying of Italian Tony. Ronnie admitted in his recent autobiography, Memoirs and Confessions, that he had ordered Mr Tony Zomparelli’s killing in 1970. He said the Italian-born gangster was assassinated in revenge for the murder of his brother, David, who died after a fight at the Latin Quarter nightclub in London’s West End.

One particular night, when Dot and Emily were having a drink in the A&R Club, a man ran through the bar being pursued by a knife-wielding gangster. He jumped through the window landed on the sun canopy below then jumped to the ground and beat a hasty retreat. What was amazing is that no one took a blind bit of notice; they just carried on drinking as if it were a normal occurrence. Mickey Regan, Ronnie Knight’s business partner, turned to Emily, patting what can only be described as a gun-shaped bump beneath his jacket, and said ‘Don’t worry Em if anyone touches you, you just tell your uncle Mickey’. Dorothy, having over imbibed of the Amontillado Sherry, decided it was time to go. Exiting the club she saw a taxi that wasn’t displaying a light. Undeterred by the fact that the taxi wasn’t for hire, she got in. The driver, who just happened to be the actor, Bernard Breslaw’s brother, Stanley, told her he was off duty. Dorothy, who was in a particularly cantankerous mood that night, refused point blank to get out and gave instructions to be taken to the Embassy Club. No amount of cajoling could persuade her to leave, so Stanley attempted to bodily drag her out.

She fought like a wildcat resulting in Stanley being kicked in the head. Bleeding, he returned to his seat, locked the doors and drove the disruptive diva to Strand Police Station where she was charged with ‘Unlawful assault, hereby causing actual bodily harm, contrary to Section 47 of the offences against the persons act’. She was fined costs of £130.

Dorothy seemed to like being linked with dangerous characters, as a lot of showbiz personalities do. It was even rumoured that Dorothy had had an amorous assignation with one infamous gangster in her office in Oxford Street. (I won’t mention which one it was as he may still be with us and I’m quite fond of my kneecaps.) Dorothy’s predilection for gangsters intrigued me and I persuaded her to take me to a pub in the East End of London, which was believed to be frequented by the Kray Twins. I’d heard tales of London’s gangland from my father, who’d been around in the days of Jack Spot, the king of London’s gangland, before the Krays were born. Now I was about to experience it first-hand.

I was shivering with excitement as I followed Dorothy into the smokey up-beat atmosphere. The pub was full to bursting. The men had a charismatic if dangerous air about them with their large muscles and goodness knows what else bulging beneath their shiny mohair Italian-cut suits. The smell of sweat mingling with the scent of Old Spice and Californian Poppy, worn by the pretty mini-skirted girls with their beehive hairdos and winkle picker stiletto high-heeled shoes, only added to the sleazy but exciting atmosphere. Dorothy had heard that a jazz organist called Lennie Peters, whose uncle was Charlie Watts, the drummer of the Rolling Stones, was playing there that night and she wanted to check him out. Lennie had been blinded in a brawl when he was 16 but this didn’t deter him from being a great keyboard player or, later, from becoming a huge star as part of a duo called Peters and Lee. As we listened to the sound of jazz coming from Lenny’s Hammond organ, with its twin Leslie speakers spewing out the sound of ‘The Cat’ by Jimmy Smith, I could see why Dorothy found it exciting to be rubbing shoulders with the underworld; it was intoxicating. The colourful scene was reminiscent of a Damon Runyon novel. I was still high on the atmosphere when we returned to St Mary’s Mount to drink tea in the tranquillity of Dot’s kitchen.

2

The Early Years

The luxurious life at St Mary’s Mount was a long way from the coal, tin and chapel culture of Llanelli: the Tin Works with its tall chimneys spewing out vast grey clouds that billowed and hung over the town, the row of terraced houses that clung to a mountainside, where Dorothy had been brought up, and the turbaned girl dressed in crossover overalls, who’d worked like an automaton on an assembly line. It had certainly been a long hard road from the Tin Plate Works to Tin Pan Alley. Life hadn’t been easy for the young Edna May or Dorothy as she later became. Her story began with her birth in a gypsy caravan in Dafen, South Wales. She came from a showman family; her grandfather ran rides on Stutz Travelling Fairground and Archie, Edna’s father, ran a coconut shy. Archie was a gambler and womaniser who was often absent, which made life tough for Dorothy’s mother, who had to bring up Dorothy and her two siblings, Rene and Fred, virtually single-handed.

Dorothy was the rebel of the family. She wasn’t content to fit in like the rest; she had theatrical ambitions. She’d got the bug for singing at an early age. She remembers the St David’s Day school concert and schoolgirls wearing an assortment of daffodils and leeks, standing on a makeshift stage of railway sleepers. The diminutive Dorothy, dressed in a smock dress, jostled for position amongst the much bigger girls. She stumbled and fell, her little glasses trampled underfoot. She turned defiantly to face the much older girl, fists raised ready to fight for her position, her feisty spirit that would take her to the top of her profession evident even at that early age. Accompanied by an out of tune piano, the choir launched lustily into ‘Calon Lân’ but the only voice the audience were aware of was that of Dorothy’s, pure and strong. She recalled:

I was the only small kid in the choir – a little Dwt – the short arse with all the grown-ups. I had beautiful clothes. Dada loved me in my beautiful clothes but he’d never let me have shoes – always boots. I was like a fairy with little white boots. I remember the stage was made of railway sleepers that sounded like a xylophone when I walked on it.

At 15 Dorothy went to work in the tin plate factory but she was a free spirit and hated the confinement and discipline of the factory floor. Her only escape from the drudgery of the assembly line was the local fleapit of a cinema where she would watch spellbound as Al Jolson lit up the silver screen. She saw the Jolson Story twelve times. Seduced by the glitz of Hollywood she dreamed of becoming a star. She was often ridiculed by her workmates for her ambitions, which often led to full on fist fights and she bore the scars to prove it.

A cacophonous catfight started when a tough looking girl, fed up with Dot going on about being a singing star, told her that she’d never be a star as long as she had a hole up her arse. Dot made a grab for the girl and a lot of kicking and screaming broke out. The foreman tried to break it up and got a smack in the eye for his trouble. He told Dot that if she didn’t toe the line he would have no alternative but to sack her. The uncompromising Dorothy told him to stick his fucking job, she didn’t need it; she was going to be a star and she stormed out clutching yet another pair of smashed spectacles. This didn’t go down too well at home, not only because of the loss of a much-needed wage but because the foreman just happened to be Dorothy’s older sister Rene’s husband, George.

Dorothy was now out of work but glad to be free of the factory. She kept body and soul together by babysitting, running errands and scrubbing kitchens. She would even forage for coal on the smouldering slag heaps that surrounded the town, resulting in her knees being peppered with indelible blue scars where the coal dust had penetrated her young skin. To say that Dorothy wasn’t very good with money would be an understatement; as soon as she earned a few bob from her efforts she would blow it on the cinema. This extravagance would prove to be the pattern for her entire life and was undoubtedly a contributing factor in her eventual downfall.

Determined to break into show business she bought a battered old ukulele from a junk shop; she wanted a piano more than anything but her mother couldn’t afford it so she had to do with a ukulele instead. She practiced singing Al Jolson songs in the Ty Bach – the toilet at the bottom of the garden – and would try out her new-found talent on the local boys of the village. Little did the naive Edna May realise they were more impressed by the size of her breasts than her vocal skills. When Dorothy joined a local dance band called the Denza Players, her father Archie was dead set against it. Being the womaniser that he was, he was frightened she would see him out at the local dance hall with his bit on the side. Dorothy undaunted, and aided and abetted by her long-suffering mother, would climb out of her bedroom window under cover of darkness. Her mother would lower her suitcase out of the window on a piece of rope and Dorothy would change in an adjacent phone box. It can’t have been a nice experience stripping down to her underwear in a cold smelly phone box that had been used for activities other than communicating. Undaunted by the smell of bodily excretions, she would don her brown dance frock with a silver star on the front then totter off down the road in her dangerously high-heeled silver shoes to do her five-bob gig.

The rows with her father and the constant taunts of her friends took their toll and the situation for Edna May became intolerable. So, with little more than hope, courage and the price of a one-way ticket in her pocket she decided to leave for the bright lights of London. Dorothy left Llanelli early one morning before her father was up. An icy wind was blowing through the station, which was deserted save for a porter and a drunk sleeping it off on a bench. The 16-year-old Edna May, clutching her bag that contained her few meagre possessions, shivered more from excitement than cold as she contemplated the adventures that lay before her. Betty, her school friend from Pwll arrived just in time to see her off. They hugged each other for a moment and Dorothy, with tears in her eyes, promised that when she was a big star she’d send for her. As the steam-belching train bound for London pulled out of the station, Dorothy looked back to the already diminishing figure of Betty and wondered, for all her well-intentioned promises, if she would ever see her best friend again.