Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

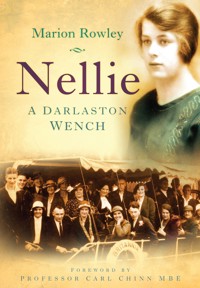

Nellie White (nee Askey) was born in 1906 and brought up in a working-class Darlaston family. Her daughter, Marion Rowley, has compiled this book from memories passed on by Nellie, and the result paints a vivid picture of the Darlaston that has disappeared. The folk who walked the streets of this bustling little town and lived in its back-to-back houses would not recognise it today. The changing face of Darlaston is discovered here, set against the backdrop of Nellie's own life, and we see her through childhood and schooldays, times of privation, teenage years and marriage. Nellie's memories were recorded during her old age, and she recalls in astonishing detail the minutiae of everyday life in this part of the Black Country during the first half of the twentieth century. This book will be a valuable record of days gone by and is sure to appeal to those interested in the social history of the Black Country.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 184

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Nellie

A DARLASTON WENCH

This book is dedicated to my parents, my late husband Derek and our three girls, Margaret, Katherine and Jennifer

With special thanks to Carl and Jean for their help and inspiration

Nellie

A DARLASTON WENCH

Marion Rowley

First published in 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Marion Rowley, 2009, 2013

The right of Marion Rowley to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5243 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Foreword by Professor Carl Chinn MBE

1

‘A Bonny Little Gel’

2

Coronation Day

3

Scarlet Fever

4

Lil

5

A Good Knees Up

6

A Plot is Hatched

7

A Lesson Learned

8

School Days

9

Pastimes & Tradesmen

10

War

11

On the Move Again

12

Christmas

13

‘Come Quick, Me Mother’s got the Bellyache’

14

‘Boneshakers’

15

First Job

16

Nancy

17

Town Hall Dances

18

George White & ‘The Pay Mon’

19

Loss

20

Goodbye Jim

21

Marriage

22

Albert James (Joe)

23

A Home of Their Own

Foreword

by Professor Carl Chinn MBE

Born on Sunday 8 July 1906, Ellen Leah White, nee Askey and better known as Nellie, was proud of coming from and belonging to a working-class Darlaston family. Her daughter, Marion Rowley of Sedgley, thoughtfully sent me her mother’s account of the lives of the people of her town from 1906 until the 1930s. She told me ‘my late mother had total recall of those years and I made several tapes, one of which the Black Country Society was happy to add to their archives. It is very important to me that her accounts of those times are not lost to a new generation.’ I agree with Marion’s sentiments and I am honoured that she has shared with me her Mum’s words; for this memoire is unlike most life stories that are written in literary language and can sometimes be stilted and distant from their subjects. By contrast it sets down the speech of Nellie and the people to whom she belonged in a simple, vital and compelling way.

As such it has a power to engage us with the everyday life of one family, but through whose actions, thoughts and expressions we catch hold of shared values, shared identities, and shared experiences. Herein lies the vigour of Nellie’s story: for all that it is hers it is our too. In harking at her words we hear once again our grans and granddads, our moms and dads, our uncles and aunts, their neighbours, and all those who toiled and moiled through the tough times of the inter-war years, hoping, one day that their children or their children’s children would have a better life. Through Nellie’s eyes we see the streets not only of industrial Darlaston but also of the industrial West Midlands, and through her soul we feel the stirring of all those who suffered want and adversity in a wealthy land and still strove to stay proud, clean and respectable.

Nellie pulls us into a tough working-class life in which you had to lie on your bed and make it as best as you could; and yet for all that poverty was a fact of life. Nellie and her people did not live in isolation seeking only to look after themselves. Selfishness was a sin they knew not. In spite of privation and family fallouts they clung to kin and neighbours and forged strong ties to one another. They had to, for there was precious little help from the rich or the state. Working people had to make do and mend. And make do and mend they did through reaching out to each other and adopting as many coping strategies as they could in the face of that hard enemy called poverty. Crucially their world was not one of me and mine, it was a world of us and ours. This then is the story of the earliest memories of Nellie: A Darlaston Wench, the daughter of Annie and Jim Askey who always held fast to the principles instilled into her by her people and whose words now keep her people alive though they be long gone.

1

‘A Bonny Little Gel’

The old midwife held up the newly born infant by the ankles, giving it a smart tap on its bottom. At first it remained inert, as if reluctant to fill its lungs with the air of the world it had just entered. Another slap administered by Nurse Shaw persuaded it to open its mouth and bawl lustily in protest.

‘There you are Annie, her’s right as nine pence and by God her’s a big ’un.’ Nurse turned to smile reassuringly at the strained face of the anxious mother before carefully weighing the baby.

‘What did I tell you, 12lb 10oz, not as heavy as George – he was 14lb if I remember right – but this one’s a bonny little gel.’

After washing the baby and wrapping her tightly in a shawl, Nurse placed the snuffling infant into its mother’s arms.

‘Now I’ll just tidy round a bit’, she said, ‘and Jim can pop up and see you, then I must see about getting home.’

Nurse Shaw glanced at her watch, noted that the time was 12.15 and hoped that her Sunday roast was being attended to.

‘Would you open the window, please’, asked Annie faintly, pushing back dark strands of hair from her hot forehead. Nurse moved obligingly to the window, pushing it up with difficulty. The fresh summer breeze entered the stuffy, sickly-smelling room behind her as she leaned out for a moment, looking up and down Station Street, noticing a handful of ragged urchins squatting on the hot, dusty, blue bricks. Footsteps passed directly underneath the window, and leaning further out, Nurse Shaw saw that it was Jim Askey, who had slipped out for a much needed pint.

‘There’s Jim, Annie, I’ll just give him a shout!’

She bustled to the door and in response to her call there was a heavy tread upon the uncarpeted stairs and a moment later Jim poked his head a little nervously round the door.

‘It is all over then?’ he asked.

‘It is, Jim’, beamed Nurse, ‘and you’ve got a lovely little girl, her’s a whopper, 12lb 10oz.’

Jim’s eyes met his wife’s questioningly as he moved over to the bed.

‘You all right, Annie?’

‘Course I am’, she replied, adjusting the shawl so that he could get a good look at his new daughter.

‘It weren’t half as bad as when our George was born’, she continued, ‘d’yer remember what it was like when we had him?’

Did he indeed, Jim was never likely to forget. He was a bricklayer and had been out of work for sixteen weeks because of heavy frost and then he’d been kicked by Charlie Simmons’ horse, breaking a leg. There was no unemployment money then and they had survived on a diet of Swedes and dripping supplied by an old aunt of Jim’s. When George was born Annie had been attended by Nurse Shaw and she would always be grateful to that kind old lady who had brought her a basin of gruel and refused the 2s 6d. Annie had saved to pay for her confinement.

Times were a little easier now, eighteen months later. Jim had regular employment and could afford to feed his small family adequately. He turned to the Nurse who, having finished her ministrations, was making ready to leave.

The Vine.

‘How heavy did’st say her was?’

‘12lb 10oz’, she replied somewhat surprised by the sudden interest in his daughter’s weight.

‘Well you see, I’ve just heard ’Lijah Brown down at the Vine braggin’ about the baby his missus has just ‘ad and it was only 5 lb!’

‘’Ere then,’ Nurse Shaw reached over and took the baby from its mother’s arms, handing it to Jim.

‘You tek her down and let ’em have a look at this one. I reckon you’m got sommat to brag about!’

And so it was that on Sunday, 8 July 1906, when Ellen Leah, later to be known as Nellie, was less than two hours old, she was placed on the counter of the Vine and toasted by Jim and his pals and a slightly subdued Mr Brown.

2

Coronation Day

Nellie sat on the Mission wall in a state of confusion and excitement. She was now nearly five years old and barely able to comprehend what all the noise and cheering was about. That morning her mother had combed her hair and, dividing it into two bunches, had tied them tightly with red, white and blue ribbons. Her face had been subjected to a vigorous scrubbing until it shone like a shiny little apple. She wore her best red plaid dress with the sailor collar, covered by a crisply starched, white pinafore. Seven year old George had also received his mother’s special attention, protesting loudly at the scrubbing and the tight uncomfortable celluloid collar, which bit into his neck.

‘Do I ’ave to wear this, Mother?’ he pleaded, rubbing a finger inside the collar.

‘Yes, yer do’, insisted Annie, ‘an’ it’s no good goin’ on neither. I reckon as all the rest o’ the kids’ll be dressed up today so shut up moanin’.’

Once the children were attired to her satisfaction, Annie set Nellie on the kitchen table in order to fasten the tiny buttons on her boots, then lifting her down, she turned to George.

‘Tek Nellie down to the school as quick as you can, they’m givin’ all the children a present or somethin’ today so mek haste or there’ll be nothin’ left.’

George had needed no second bidding. Holding his little sister’s hand tightly, he pulled her out of the dark kitchen into the brilliant sunshine outside.

There had been an unusual number of folks about that morning. Women stood on their freshly ochred doorsteps to gossip. The houses were gay with bunting and there was a general atmosphere of excitement.

When Nellie and George arrived at the steps of the little Mission School, which Nellie had begun to attend when she was just three and a half years old, numbers of their schoolmates, all presenting an unfamiliar clean and tidy appearance, jostled with each other when requested by the teacher to form an orderly queue. Along with the others, Nellie received a celebration mug, a medal and an orange. Carrying these carefully she had followed George home and as they turned the corner into Heath Road, her mother had been waiting anxiously, in case the children should spoil their best clothes.

The Askey children.

Annie with Nellie, Tom, George and Evelyn.

Jim arrived home early from work that day along with some of his mates and he now stood behind Nellie, his hands encircling her plump waist, in case she should slip from the wall. She wouldn’t realise until she was older that all the excitement, cheering and the procession she was about to witness on that June day in 1911, were in celebration of the Coronation of King George V. Annie, Jim and Grandad Tom remained seated on the wall with the children, chatting to a few neighbours, long after the general crowd had dispersed. Nellie climbed onto her grandad’s lap and laid her head against his waistcoat. She could hear the faint tick, tick of his pocket watch and as his arms moved to settle her more comfortably, the heat of the afternoon sun on her uncovered head and the steady ticking of the watch combined to make her feel drowsy. Her eyelids began to droop heavily until she fell fast asleep, remembering no more of the eventful day until her mother’s hands removing her boots woke her briefly, as she was laid down on the hard wooden squab.

3

Scarlet Fever

Jim’s father, Tom, was a spry old man and Nellie’s memory retained a clear vision of him long after his death. He usually wore a cloth cap and rough jacket together with a pair of baggy corduroy trousers. He was quite a small man, although all four of his sons were well above six feet. He had fought through the Crimean War and his service to his country had resulted in the loss of an eye, which he covered with a black patch. Nellie recalled her uncles would pull his leg after hearing him recount some of his more hair-raising exploits. They would infuriate him by laughing and telling him ‘Yo fought that war wi’ sticks and bladders!’

Although the house in Heath Road was tiny, consisting of two rooms up and down, Annie and Jim were happy to accommodate the old fellow. Indeed, Annie was often grateful for his presence as he would take the children off her hands when they were not at school. He took them for long leisurely walks to Bentley Common, or they would enjoy a visit to James Bridge cemetery on a fine afternoon, wandering around the gravestones, Tom laboriously reading out the worn inscriptions for the children’s edification.

One hot Sunday afternoon, soon after the street celebrations, they set out in the direction of Forge Lane. Stopping frequently to rest and enjoy the warm scented breeze, Nellie had loosed her grandad’s hand and had wandered off alone to pick a few wild flowers for her mother. She knelt down on the rough verge near a clump of wild poppies and then quite suddenly she felt that it was too much trouble. Her head ached and she felt strangely wobbly. Dropping the few wilting flowers from her hot little hand, she rolled over and lay on her side, her head on a patch of dusty grass.

Tom and George soon became aware that Nellie was not trudging behind. With a cry of alarm, they looked back to see the tiny figure huddled by the roadside. George reached her first and was attempting to raise her to her feet when the old man came hurrying up. ‘Out o’ the way lad’, he panted ‘let’s see what’s up wi’ her.’ He knelt down on trembling knees and peered anxiously out of his good eye at the flushed, tearful face of his granddaughter. ‘There’s summat the matter wi’ her all right’ he announced. ‘Her looks real poorly to me, we’d best get her back ‘ome as quick as we can.’

Tom’s wiry old arms still retained sufficient strength to lift the little girl and he hurried along as fast as he could go.

‘Thee run on and tell thee feyther or thee mother George, and just be careful crossin’ t’hoss road!’

Nellie lay whimpering in her grandfather’s arms, hearing his hoarse laboured breath as he struggled up a sharp incline. All the time he kept talking to her, telling her she was his best little wench and she’d soon be better. He could have wept with relief at the sight of Annie and another woman approaching. George must have put every effort into his flight home.

The pressure on Tom’s arms eased as Annie took the child from him. ‘No need to kill yerself Dad’, she rebuked him. ‘I dare say it’s not that bad but Jim’s gone for Dr Magrane.’

The neighbour, Mrs Lucas, peered at Nellie, lifting her clothes between grimy fingers. ‘I can tell thee wot’s the matter wi’ her, Annie’ she announced. ‘Her’s got the scarlet fever!’

‘Am yer sure?’ cried Annie.

‘As sure as I can be’ nodded her neighbour with just a hint of smug satisfaction. ‘I’ve seen it before and yer know as the Doctor won’t let yer keep her at ‘ome if he knows you’ve got a lad as well, it’s infectionous yer see.’

When Nellie heard these words she immediately tightened her hands into a stranglehold round her mother’s neck and broke into a loud wail. Annie struggled to loosen her grip. ‘Now stoppit Nellie. Yer won’t ‘ave to goo anywhere if yer shut up.’

At the little procession approached Heath Road, Annie had decided what she must do. Before reaching the house she whispered a few words to George, who nodded his head and turned to trot back down the road, before disappearing into one of the long entries.

Dr Magrane was the parish doctor and had once been a naval surgeon. He visited his patients driven in a smart pony drawn trap by a man named Mr Ray, who looked after the pony and saw to the general upkeep of the trap. The Doctor arrived at the house shortly after Nellie had been laid down and bending over, he quickly confirmed Mrs Lucas’ diagnosis.

‘Are there any more children in this house?’ he asked Annie.

‘No, Doctor’, she replied without hesitation.

‘Good, good’, said Dr Magrane, ‘in that case you can nurse her at home. I want you to go to the Town Hall first thing in the morning’, he continued. ‘Ask for some disinfectant and you must be sure to use it everywhere and in all the washing. Call for me if you are worried and I would advise the other members of the family to sleep downstairs.’ After a few more words of advice, the Doctor left. Jim followed him to the door and when the trap had disappeared smartly round the corner, he turned to Annie and asked in some bewilderment ‘Where’s George and why did yer tell the Doctor Nellie was the only one?’

‘George is goin’ ter stop wi’ your Sarah for a bit, else Nellie would’ve ‘ad ter go to the Fever Hospital and I can look after ‘er just as well meself.’

Later, with Nellie tucked up in her tiny bedroom, two mattresses were hauled downstairs while Annie fixed a sheet over the doorway to Nellie’s room. She would manage on a chair beside the bed for a few nights, she told herself. It would be better than traipsin’ up and downstairs all night disturbing the men.

4

Lil

Jim’s Dad had no permanent home of his own and would stay for a short time with each of his sons in turn. Within a few days of Nellie’s illness, during which time he and Jim were confined to the ground floor, Tom decided it was time he was on the move.

‘Yo cor hardly swing a cat round in ‘ere’ he complained to Annie. ‘I’d best goo and see our Sam for a bit. You can shift one o’ them mattresses back upstairs then.’

Annie was secretly relieved, although she would not have hurt the old man’s feelings by letting him see. ‘Please yerself, Dad’, she said. ‘We’ll let yer know as soon as Nellie’s better. I expect as Sam and Cal will be glad to see yer.’

Tom left later that morning after helping Annie upstairs with his mattress and getting together his few belongings. As soon as he had gone Annie decided to give the room a really good clean as this had been almost impossible to do properly with the room being so small, normally slightly cluttered and then filled to capacity with the two mattresses.

She seized the remaining mattress and struggled to heave it into the backyard, to be followed immediately by two pegged rugs. After filling a chipped enamel bucket with hot water and soft brown soap, she fell to her knees and began to scrub the red quarry tiles. While the floor was drying, she went outside, took up one of the rugs and banged it hard against the wall, sending the dust flying in a choking cloud.

‘’Ow’s your Nellie today, then?’ croaked the husky voice of her next-door neighbour, who had appeared at her door upon hearing Annie’s strenuous efforts outside.

‘Oh her’s a bit better’ coughed Annie, dust clogging her throat. ‘I wish I could get ’er to stop scratchin’ though. I’ve plastered ’er wi’ calomine lotion but it don’t seem ter do much good.’

Annie was reluctant to waste time talking today, although she was usually prepared for a good gossip when she had the time to spare.

‘I thought I’d ‘ave a good clean-up today’, she told her friend. ‘Nellie’s asleep, Jim’s out of the road and his Dad’s gone to stop wi’ Sam for a bit.’

‘I thought as I ’adn’t seen ’im about this mornin’’, nodded Mrs Lucas. ‘Still, it’s less for you to do while Nellie’s in bed.’

‘I suppose so’, agreed Annie. ‘Her’s no trouble really but ’er ’as been that poorly that I’ve ’ad ter sit with ’er and I can’t get out to the shops. I was wonderin’ if you’d be gooin’ up the town today?’

‘I shall be later on, what dost want me to get?’

Annie considered, ‘Well I could do with a loaf and I think I’ll mek a stew for Jim’s supper. He’s werkin’ late today. Could yer get me three pennorth o’ bits and some onions. That’ll do ’cos I’ve got some carrots and parsnips. I’ll just slip in and get me purse’.