Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

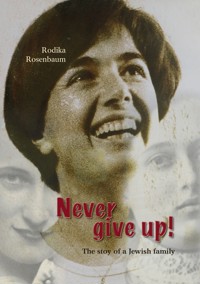

The book chronicles the story of the Rosenbaum family, a pseudonym, spanning the period from 1896 to 1970. It begins in Romania and Hungary and extends into the post-war era, during which the family initially emigrated to Israel and later, ironically, to Germany. It tells a story of uprooting, loneliness, failure, and loss during challenging times, but also of success and the strong determination that accompanied and sustained a family: "Never give up, no matter what!"

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 155

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedication

When my mother passed away, I realized in a profound way that life is finite, and I understood how much we can miss out on in our mutual relationships, things that can never be regained. A truism, you might say! But through her death, I internalized this truth. Now, I am ready to honor her memory through this book, by portraying her life story and her vitality. I want to acknowledge her immense influence on my life and our lives, in every aspect, even if I didn‘t always think that way.

Content

Dedication

Introduction

Zseni Farkas, nat. David

Letter to My Descendants

Part I

My Mother Zseni

My Uncle Mihály and a Ring for My Finger

Kindergarten and School Years

My Brother Laci – Thank God, a Boy!

Going to school

Life in the country and the consequences of the great depression

Return to the small town

Father’s return

My education

1940 – The Hungarians return

1941 – A Fresh Start in Budapest

The Family in Budapest

Breitner Pista

1944 – German Invasion

September – In the Hail of Bombs

October – Signs of Life

In the Brickworks

November – Death March

New Arrivals

January – The Liberation

Living Again

1945 – Return to Oradea

Imre – Surviving in the Shadows

Nevertheless – Never Give Up

Childhood and Youth of Feri

1925-1941 From Tailor to Forced Laborer

Escape 1944

A Fateful Encounter

Part II

A New Life Begins

The Shadows of My Mother‘s Past

Shadows of My Father‘s Past – Marika

My Life in Cluj

The Friendly Neighbor – Uncle Varga

The Dancer – Aunt Lulu

My Friend Peter

My Parents‘ Friends

Summer Days

Emigration Plans

1958 – We Emigrate

On the Ship to a New World

Israel

Karkur – Grandfather Deszö

Pardes Hanna – Uncle Israel

Karkur – Uncle Zwi

Moving to Givat Nesher

Mrs. Szabó

Moving Plans Again

1959 – Boarding School

Germany

1960 – Munich

The Arab

1968 – The Marriage

1969 Berlin – The Blessing and Curse of Learning

Epilogue

Acknowledgment

Introduction

In this book, I have attempted to piece together the puzzle of my family‘s history using the fragments my mother shared with me. This narrative includes autobiographical elements and is primarily based on factual events. It is enriched by fictional elements that seemed necessary and coherent for the flow of the story.

Through this text, I also aim to remember my two step-siblings and their mother, who perished in the Holocaust, as well as my grandmother. They should not be forgotten. I wish to contribute to the remembrance of a difficult period in European history. As long as we, the Second Generation Jews, are still alive, we should continue to pass down these stories so that future generations can learn to handle their history responsibly and consciously.

My ancestors lived in Transylvania, which was part of Hungary at the beginning of my grandmother‘s life in the late 19th century. By the time my mother was born, it had become Romanian, and in the 1940s, it once again became Hungarian. Today, it is once again part of Romania. Just as the history of this region has been tumultuous, so has been the life of my family.

Through these stories, I also aim to shed some light on life in the Eastern part of Europe during that time, which practically faded from the consciousness of many West Germans after the establishment of the Iron Curtain, even though many have their roots there.

The oldest stories I can share originate from my grandmother, Zseni Farkas. She was born in 1896 in Transylvania, also known as Siebenbürgen. Her life is recounted from the perspective of her daughter (my mother). I let my mother, Ibi, narrate the lives of my grandmother, herself, and my father, Feri, from the first-person perspective.

Zseni‘s beautiful, somewhat melancholic portrait still hangs in my living room today, and as I gaze upon it, I sometimes wonder what kind of letter she might have left for us, her descendants.

Zseni Farkas, born David 1896 – 1944

Letter to my descendants

Dear family,

One might always assume that I had a terribly sad life, like all the others born just before the turn of the 20th century. The First World War stole our youth, and in the Second World War, we were persecuted because we were Jews. But there were also good times ...

In the 1920s, I was quite progressive for our circumstances and worked as an assistant in a law firm. Unfortunately, that didn‘t appease my grandmother; she always worried that I couldn‘t manage without a husband, and ultimately, I was expected to bring children into the world. So, I conformed to her traditional notions and agreed to a marriage. That was between the wars. I had three children, whom I initially raised with my husband.

Yes, they were difficult times, and yet glimpses of happiness would often shine through, such as the affection of my husband, expressed through small gestures of love, especially in the early days of our marriage, even though it was not a love match for me.

Then there were the children, brave and clever, who often prevented me from giving up. With their determination and ideas, they kept our little family alive, especially after their father had to leave us during the Great Depression to seek his fortune in Latin America. Unfortunately, he didn‘t find it there, and when he returned, the world had changed, and evil had entered the grand stage in the form of fascism, which would become our trap.

But before that, there were sunny, carefree days in Budapest with my wonderful daughter, Ibi. We spent hours in street cafés, laughing and sharing secrets like close friends, experiencing moments of joy with friends and our children, as is customary in families around the world.

Later, our lives were dictated by anti-Jewish laws. My husband and my son, Laci, were conscripted and taken away for forced labor. As the ghetto closed in around us, I could no longer protect my children. I pleaded with God to let us survive – I would rather die than see harm befall my children. Fate spared them from death and from witnessing the Hungarian Nazis, the Arrow Cross, taking me away in November, sending me on one of those infamous death marches ...

So many stories from my generation have now become legends, and I am grateful to have lived on through the voice of my daughter, Ibi. And now, it is up to my granddaughter, Rodika, to write down our stories.

For that, I thank all of you!

Yours, Zseni

Ibolya Farkas 1920 - 2004

I was born in 1920, a year after the Romanian-Hungarian War, and I was a lively child. At just nine months old, I started walking and talking. My mother Zseni always liked to tell the story that when she called for my father from the kitchen, I said to her, “Deszö tata lova.” This phrase perfectly reflected the twisted language situation: My father, named Deszö, was with the horses, and “lova” means horse in Hungarian. However, “tata” is the Romanian term for father. So even though I was so small, I had already adopted the language mixture that spread after Transylvania was taken over by the Romanians in 1918. At that time, Romanian had displaced Hungarian as the official language of administration but not as the vernacular language among the population.

I was given a Yiddish name, Jiddes after Judith, which was my grandmother‘s name because it was a tradition back then to pass on the names of grandparents to grandchildren. Additionally, I was given the Hungarian name Ibolya, which means violet.

My mother and I had an unusually intimate relationship for that time. She told me many things about her life, especially when I was older, including stories from before I was born, when she was still a young girl. Those were beautiful mother-daughter conversations, almost like those between friends, and now I can share her stories in this place.

My mother Zseni

Zseni often traveled from Transylvania to Budapest as a young woman, where her brother Mihály lived and worked as a jeweler. It was uncommon for a young woman to travel so much and be so independent at that time.

During one of her visits in 1917, she met the brother of her sister-in-law, who was also named Mihály. They fell in love, and although he wasn‘t Jewish, Zseni‘s love was so strong that she was willing to wait for him until the end of the war. When he returned from the war, he wanted to ask her mother for her hand in marriage. However, this posed a significant problem because it was customary for marriages to be between Jews only. But Zseni was confident that she could still marry Mihály, as her brother had also married a non-Jewish woman. Love had prevailed for them as well.

The Romanian-Hungarian war followed the First World War, and the borders between the two countries were closed. Zseni could no longer travel to Budapest, and the prospect of seeing Mihály again became distant. Her traditionaly minded mother, Sahra, now suspected that Zseni had fallen in love in Budapest and wanted to reason with her in serious words: “Soon you‘ll be an old maid. At 25, you won‘t find a husband anymore, and before I die, I want to see at least my grandchildren. Besides, in these times, we need a man in the house to protect and provide for us.” “But mother, I work at Dr. Termesi‘s law firm, I bring money home, I‘ve trained as a legal assistant. You‘ll see, I‘ll bring even more money home if I stay longer,” Zseni tried to convince her mother Sarah, but she was still old-fashioned: “My God, child, who ever heard of such a thing! A woman belongs in the kitchen, not in some office full of men. I was too lenient in allowing you these whims. I‘m already old, I won‘t be around much longer, and you‘ll die as an old maid. I want to see you taken care of, the whole family is gossiping about you not being married, as if something‘s wrong with you. I would be at ease if I could see you with a husband, it would bring peace to my life. Look, Mrs. Steiner was here a few days ago, she has a good match for you: a young, hardworking man. A merchant, passing through, and he mentioned you to her. He must have seen you somewhere, I have no idea where!”“Ha, probably in the Synagoge!”, answered Zseni without enthusiasm. 1

“Anyway, he asked her to arrange a marriage because he had fallen for you. He served in the Hungarian army, even received a bravery medal, a true Hungarian, but now he wants to settle here – a devout, religious, decent man! Eligible men don‘t come to town so often! Zseni, be reasonable, after such a war, there aren‘t many young men who would be suitable. Comfort your mother, don‘t you want children too?!”

That‘s how my grandmother Sarah pleaded with my mother until, after some time for consideration, she reluctantly agreed to the marriage.

In February 1920, Mother married Deszö Farkas. I was born in November – evidently, we were all in quite a hurry!

My mother wasn‘t happy being married to Deszö. The difference in education between them was too great, and she didn‘t feel entirely comfortable with her husband, who remained a stranger to her. Even after the birth of my middle brother, Laçi, in 1923, she considered separating, getting a divorce – an outrageous thought at that time. But she only told me about it much later, when we were together in Budapest in 1944. However, my father, in contrast, loved her with all his heart until the end of her life.

1 Shiduch

My uncle Mihály and a ring for my finger

In 1923, my mother‘s brother, Mihály, finally visited us. Due to the border closures, he couldn‘t attend my mother‘s wedding or be present for my birth. There was no mail, no train traffic between the two countries, so he didn‘t even know that his sister had married in 1920 and had since given birth to a little daughter.

I didn‘t speak a word to him. He was puzzled, leaned down towards me, pulled me close, and asked, “Why don‘t you like me?”

“Because you didn‘t bring me a ring as a gift!” I said firmly, pointing to my finger. Six weeks later, a messenger arrived from Budapest, bringing me a ring engraved with “Ibi.” We had to wrap a lot of thread around the ring to make it fit, but I wore it proudly and loved my Uncle Mihály deeply and fervently from then on.

Ibi, four years old

Kindergarten and school years

A year later, I started attending a Romanian kindergarten. The kindergarten teacher asked for my name.

“Farkas, Ibolya, but they call me Ibi.”

“That doesn‘t sound like a Romanian name. What does Ibolya mean?” she asked impatiently.

“Violet, Mrs. Kindergarten Teacher,” I answered timidly.

“Alright, from today on, your name will be Violetta,” she decided, and I simply nodded.

When I got home, I ran excitedly to my mother and exclaimed, “Mom, my name is now Violetta!” Outraged, my mother turned to her husband. “How is that even possible? The kindergarten teacher can‘t just give my child a different name!”

But in the new documents, I was now listed as Violetta, until I started school. My mother couldn‘t defend me as she didn‘t speak Romanian. By then, the entire administration had been replaced, and only Romanians occupied the offices.

There was a Romanian-Hungarian saying: “Mergem la biroság, sâ facem igazság,” which roughly translates to “Let‘s go to the office to seek justice.” The language mix-up in the saying perfectly matched the confusing situation – biroság, igazság, being Hungarian words meaning office, justice, while the rest of the sentence was in Romanian. Ironically, the saying expressed the dissatisfaction of the population with the judges‘ incompetence. Due to their lack of Hungarian language skills, they didn‘t understand the people properly and were unable to mediate or pass fair judgments. Furthermore, the people felt that the judges didn‘t really care either.

My brother Laci – Thank God, a boy!

In 1923, my brother Laci was also born. I vividly remember his birth. To see the baby, I climbed up on the table and asked the midwife, “What did the stork bring us, Aunt Luka?”

“Thank God, a boy!” she answered with relief.

“Why thank God?” I asked, puzzled.

“Because then we only have to buy clothes for one girl.”

And that one girl was me.

Of course, my brother also received a long name: a Romanian one (Vasile), a Hungarian one (László, shortened to Laci), and our family name Farkas, which is Hungarian and means wolf.

Going to school

In the early years, I learned Romanian history and Romanian poetry, which I barely understood. I simply memorized everything to be able to get by in school. Only a few remnants remained in my memory, such as this soldier‘s song, which I never forgot:

Drum bun, drum bun, toba bate, drum bun, bravi români, ura! Cu sacul legat în spate, cu armele-n mâini, ura! Fie zi cu soare fie, sau cerul noros, Fie ploi, ninsoare fie, noi mergem voios, drum bun.

Godspeed, godspeed, the drum is beating, Godspeed you brave Romanians, hurrah. With a rucksack on your back, with a rifle in your hand, hurrah. Whether it‘s a sunny day or the sky is overcast, whether it‘s raining or snowing, we go merrily on our way

And even about Stefan cel Mare2 we had to recite:

Cine bate la noapte a la port? Eu sînt bun mama, fiul tiu dorit, Vintul bate rece, ranele mã dor, Si dac tu jeste Stefan, adeverat Dute la hostire, si pentru tara, Mori, si ose fiu mormîntu Coronat cu flor!

Who is banging on the gate at night? It‘s me, good mother, your beloved son. The wind blows cold, my wounds ache. If you really are Stefan, go back to your unit, and die for your country, your grave will be adorned with flowers!

Yes, I had a good memory, but often I didn‘t understand what I was saying, and even my mother had no idea what the many foreign-sounding words meant.

In the third grade a new teacher arrived. She too asked me, “What is your name?” “Violetta, teacher,” I answered truthfully.

“Violetta, that‘s not a real Romanian name, from now on your name is Viorica,” she decided, and so the papers were changed again, and that‘s now it stayed for the time being.

This teacher, a rather strict woman, quizzed me about arithmetic. I couldn‘t answer fast enough. She became angry, yanked my hair and banged my head against the blackboard, saying, “What kind of Jewish girl is this who can‘t count?” That‘s how I became a Jew.

A teacher called Falasi had another way of punishing me.

I sometimes tussled with my classmates, but when he caught me doing that, I had to hold out my hands palm upwards. He would hit them with a cane and sneer, “Oh, now your hands are shaking! What kind of heroine are you?”

The worst part was that he was a handsome man, and this greatly outraged my girlish soul.

The punishments were varied, and we were often and seemingly gladly punished, made to stand in the corner or kneel on corn. It was as if the teachers enjoyed the power they had over us and we had no way to defend ourselves.

2 Stefan the Great