Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

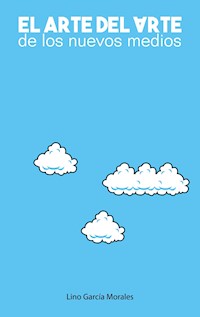

- Serie: New Media Art Conservation

- Sprache: Englisch

New media art, produced at the intersection of art, science and technology, makes up the majority of a Museum of Contemporary Art's collections. However, technological obsolescence and technical fragility of the artworks make their conservation-restoration an ongoing challenge. A new theoretical approach to permanence through change addresses this problem and offers alternatives and solutions from the production to recreation of new media art.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 140

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Hugo, Héctor and Viki.

Contents

Theories

New Media Art

Restoration of New Media Art

Methods

Bibliography

CHANGE IS THE ONLY IMMUTABLE THING.

ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER

THINGS DON’T CHANGE; WE CHANGE.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

IF WE WANT EVERY THING TO REM A IN AS IT IS, EVERYTHING MUST CHANGE.

GIUSEPPE TOMASI DI LAMPEDUSA

Theories

Restoration with a capital “R”,1 is immanent to Art, with a capital “A”. Theories of Restoration can be best described as an organized set of ideas that explain Restoration, arrived at through observation, experience, and logical reasoning, rather than as a set of rules, principles, and knowledge of the science of Restoration. One could say that they constitute a framework for action that shifts from the physical to the metaphysical in pursuit of the conservation of the identity of the Object of Restoration.

Whereas Art has many stories, the story of Restoration, which is based on the substance of the Object of Restoration, can be seen has having just two milestones or qualitative leaps. The first of these is when “indiscernible counterparts that may have radically distinct ontological affiliations” [Danto, 2011, p. 25] appear in art, and the second when the substance of these indiscernible counterparts dematerializes.

Arthur Danto proclaimed the “End of Art” when the story of Art collapsed, in the mid-1990s, at the moment when the distinction between life and its representation disappeared. Aesthetics alone could not explain this phenomenon, and so it became necessary to seek out a “philosophy of art”.

Danto sets up the problem beginning with a square of red paint described by Sören Kierkegaard. It was, according to Kierkegaard, a painting of the Israelites crossing the Red Sea, except that the painting is of the moment when the Israelites “had already crossed over, and that the Egyptians had drowned” [Danto, 2011, p. 21]. Danto proposed another “exactly equal” painting to the one described by Kierkegaard, a painting by a Danish portraitist entitled Kierkegaard´s Mood. He then proposed adding to these a landscape of Moscow called Red Square, a minimalist geometric painting also called Red Square,ametaphysical painting of Nirvana (because the Samsara world is known as Red Dust by those who deprecate it), Red Table Cloth by a disciple of Matisse, a canvas grounded in red lead on which Giorgione would have painted a Sacra Conversazione had he lived, and lastly a surface painted but not grounded in red lead that is not an artwork (and is interesting art-historically only because it is has no art historical interest) but “just a thing with paint over it”. In short, these works form a series of seven “indiscernible counterparts that may have radically distinct ontological affiliations”.

Figure 1: Danto’s seven red paintings.

Danto provides a “solution” to the problem of the red paintings with the following sentence: “The difference between art and reality is just a matter of those conventions, and that whatever convention allows to be an artwork, is an artwork” [Danto, 2011, p. 61]. Such “conventions” are displaced from the signifier to the signified.

According to Leibniz, two objects are identical if they have the same properties; Danto disagrees. He quotes Borges to “avert our eye from the surface of things” and force us to search for an answer beyond what the eye can identify (retinal indiscernibility). One could argue that the properties Leibniz observes are intrinsic to the object, while the properties that Danto and Borges observe are extrinsic to it and belong to what Danto calls “conventions”. According to Danto-Borges, these extrinsic properties of the work “penetrate, so to speak, the essence of the work” [Danto, 2011, p. 69].

A signifier can have many signifieds, depending on such conventions, the interpretive context, or the individual. Danto, however, starts from “retinal indiscernibility” to theorize on whether or not it is the same. He takes for granted that these radically distinct ontological affiliations mean that there are intrinsically identical properties. In other words, if the seven red paintings were different, there would be no meaning to the whole discussion. In some theories of Restoration, this “philosophy of art” only makes sense if the identity of the seven red paintings is conserved. Identity, in this case, exists in relation to the intrinsic properties of the Object. These are “retinal” properties, in Danto’s terms (i.e. objective, measurable, etc.). There are, however, other theories of Restoration according to which certain extrinsic properties of a work (albeit of other types of conventions) also penetrate the essence of the work, à la Danto-Borges (i.e subjective, non-measurable, etc.).

The next major leap in the story of Restoration occurs with the dematerialization of the “indiscernible counterparts”. When Danto decreed the “End of Art” there were other problems –the loss of “aura”, for example– which could only be explained in the philosophical sense he demanded. Yet Danto limited his thinking to the “Object”.

Beyond immateriality, with the emergence of computation, art objects can be virtual, ubiquitous, etc., in which case they are not indiscernible counterparts, but identical copies.

Figure 2: Axiological degradation of a work of art, where A is the original and B is a copy or transformation of A to another state of authenticity.

One could say that judgements (objective or subjective) that penetrate the essence of works are “value judgements”, understanding “value” as the scope of the signification or importance of a thing, action, word of phrase. The choice of both sets of attributes –intrinsic and extrinsic– that determine the “identity” of a work of art are value judgements, and never irrefutable truths. These values are essential (for an individual), social (for a community), commercial. . . and belong to the dynamic of a “cultural economy” in continual transmutation.

If we were to take the red painting described by Sören Kierkegaard (to the left in fig. 1) as an Object of Restoration, it is a unique, autograph work that is begotten intellectually and materially from its author2. A heterographic work comes intellectually, if not materially, from its author. It is also expected to be the original. Unicity is common in “traditional” art, and in fact, multiplicity (in printmaking, for example) is understood as a degradation of value relative to each unit. Unicity is, in general, highly valued as a thing that is singular and unrepeated, and in this regard is closely related to exclusivity and scarcity. Within these practices, multiplicity is not unusual, but it is inferior in value. The act of copying a pictorial work was a mechanism of learning rather than of representation, and the very nature of the print diminished as the print number went up. Restoration must maintain the authenticity of the work, understanding the authentic as a certification that testifies to its identity and truth.

For the purposes of the story told in this book, “‘traditional’ art” refers to what is otherwise called classical art, pre-modern art, the fine arts or, plainly, art, or even part of modern art, etc. It is the first stage of “art”, whose origins date back to the Renaissance. In short, it is art produced according to a series of formal rules, among which is a certain concern for the stability of matter and its permanence into the future; in other words, an interest in its conservation. This is what I mean by “tradition”.

This tradition was thrown into crisis by the desire to blur the boundaries between art and life. The emergence of photography in 1839, film in 1895, performance in 1900, conceptual art in 1917. . . gradually broadened the concept of what hitherto had been recognized as art. From a conservation standpoint, the appearance of the readymade in the early 20th century produced the final rupture with tradition.

Readymade is a term that Marcel Duchamp created to designate a reaction against retinal art3.

With the emergence of “contemporary” art (understood as “the End of Art”), multiplicity acquired a conceptual connotation. Artists copy and authorize others to copy them, and technical reproduction –a set of practices that Walter Benjamin argued destroy “originality”–was normalized. Art became an object whose value cannot be established by how it functions within the tradition. This departure is allographic in nature (variance and alternance)4, and the multiple is degraded depending on the degree to which it is a faithful representation of the reference model or example (the “original”). The contemporary art Restoration Object carries a degree of immateriality, in its use of ignoble materials alien to tradition, as well as ephemeral practices, the use of communications media as a ground or support, the idea that “every human being is an artist”, the disaffection or negation of any earlier rules “imposed” by tradition, etc. The term “contemporary” is used here, although contemporary art is normally associated with the 1950s, and is clearly indebted to modern art, and it is not always apparent where one ends and the other begins. Strictly speaking, contemporary art stopped being contemporary. . . since then.

The Restoration Object in new media art, corresponding to a third period, sits at the intersection of Art and Technology, inheriting the complexity of both. By then, the active5 contemporary art object (performance and film, for example) already existed, but new media art uses the digital computer as the ultimate remediating and metamedium, and completely expands reality. Here too there was a diffuse period of technology-related and electronic art that began in the 1960s, at the height of contemporary art, to which new media art is indebted.

In Chinese culture, for example, there are two distinct translations of the western concept of copy: the term fangzhipin is used in the sense of imitation (the copy is different from the original, and the term fuzhipin is used in the sense of reproduction (the copy is indistinguishable from the original). In western culture, both of these Chinese concepts pertain to a diminished, degraded and even disdained axiological state. In eastern culture, however, fuzhipin has the same value as the original; the distinction between original and copy is less important than the differentiation between old and new. The term shanzhai is used in the sense of reinterpretation, not falsification, where there is no intent to deceive anyone.

Theories of Restoration are still new and correspond to this narrative of the dematerialization of art simplified into three large overlapping periods of time, detached from the earlier ones, and coexisting at present. All of these theories attempt to justify the authentic B-state that a work should have, once restored. There’s a certain Russian doll effect to these theories, where the complexity of new media art absorbs the complexity of contemporary art, which likewise absorbs the complexity of traditional art.

Figure 3: The pictorial support of traditional art. It is the surface that has been handled and prepared to sustain, in a technically secure manner, the different elements that make up the pictorial work. Here, matter serves as structure. In the pictorial layer, matter functions as aspect.

The Restoration Object

A work of art is defined on the one hand in terms of its physical, intrinsic properties, and on the other its metaphysical, extrinsic properties. The relationship of these properties to the individual, and not the art object, are axiological. The intrinsic, physical properties pertain to the signifier and are meant to convey the signified. In Communication Theory, the Object, as defined by its intrinsic attributes, is the medium that contains the message, and the signifier and its extrinsic attributes act as noise, like something that is added to the message during the communication process.

From an ontological perspective, the artwork is an entity whose substance that can be separated into two: structure (functioning as support) and aspect (functioning as image). This teleological split may be irrelevant to any official story of art but is fundamental to Restoration.

The support is a system or whole, composed of organized and interrelated parts, and anything outside of this system is considered context. The image is a system of symbols, related signs that have a symbolic function.

The “system-object” is “testimony”, it is what conveys the text, the container, the signifier, Gestell. The “symbol-object” is “text”, the constituent story of the artefact, the content, the meaning, Gestalt.

The work as Object (system-symbol-object) is something abstract that is instantiated as text/testimony, symbol/system, content/container. Fetichism, to make the point, confuses the system-object (parts) with the system-symbol-object (the whole).

In traditional art, structure and aspect function respectively as support and image. They are both matter and very closely related to one another; but they are not the same.

This teleological division was proposed by Cesare Brandi in his Teoria del Restauro.6 Matter, he says, is “that which serves the epiphany of the image” [Brandi, 2008, p. 13]. The support (system-object) is matter without which the image (symbol-object) is not possible. The support is restored to the extent that it allows the epiphany of the image: for its end purpose, its telos. The aim of Restoration, one could therefore say, is the image, not the support.

Duchamp’s readymade (fig. 4) ushered in the “End of Art” in the sense Danto gave to this concept. In this work, the support is material, but the image is immaterial. The image is not what is seen (a found object lacking any aesthetic value) but what is not seen (the anti-retinal), a gesture which, through a transmutation of values (“conventions”, in Danto’s language) is inserted into cultural life. Joseph Kosuth believed that all art after Duchamp and the readymade is conceptual, “because art only exists conceptually”. It is a change in the very nature of art, from an issue of morphology to one of function.

Danto later wrote: “we might think about art after the end of art, as if we were emerging from the era of art into something else the exact shape and structure of which remains to be understood.” He used the term “post-historical” to refer to any work produced after the end of art. After the end of art, quite literally, anyone can be an artist and anything can be art; it depends only on conventions.

New media emerged as one of the things that contemporary art allowed to be art and remained conceptual. Yet new media can also be “artists”, based on code, the image being more dependent on time than space, not a “here and now” but instead an any place at any time and reliant on energy to manifest itself. It is progressive.

Figure 4: Marcel Duchamp. Fountain, 1917.

Figure 5: John F. Simon, Jr. Every Icon, 1997.

Fig. 5 shows a Java-applet7 that fills a 32 × 32 square grid with all potential permutations of white and black squares. It is possible that every potential image, including known images (faces, landscapes, objects, works of art, etc.) and unknown images will be represented in this small icon.

The Restoration of contemporary art marks the “End of Restoration”. It deals with the paradoxes and contradictions of restoring anything or things that are members of a class, but restoring them according to the terms that are appropriate for members of another class (i.e., traditional art) as if these were all the same class.

Traditional art, contemporary art and new media art, in this story8, belong to a greater narrative: the “Story of Art”. Yet they are not the story of Art. They are members, individuals, parts of the Art class rather than the class itself, or generality, everything, Art. When in Art everything is considered to be the same thing (in other words, when things are treated as more of the same when they are not, or to treat as class, object or generality what is simply a member, subject or particular) because of the immanence of Restoration in relation to its end –the work of art– an error in logical typification is committed, leading to a series of paradoxes and confusions that appear to be unsolvable and incongruent.

But this is a story of art based on image; text, in Derrida’s words. Image is figure, representation (from the Greek eikon), likeness and appearance of something. It is imitation (from the Latin imago), substitution of some things for others. It is not reality, but the “creator” of unreality. It is not something, it is the absent represented in our mind. It is sign. It can be material, deposited in a substrate, and it can be immaterial or hybrid (as in the case of cinema).9 Fig. 6 illustrates this story based on the substance of the artwork. Traditional art is Image-Material. Both support and image are material. Everything is space. Contemporary art introduces movement and time.

The Image: Movement or Time, can be material, hybrid or immaterial.