Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Over the past fifty years, Gary Newbon has established himself as an icon of sports broadcasting. He interviewed Sir Alex Ferguson after Manchester United clinched a historic treble in 1999. He was in the ring when Gerald McClellan collapsed after suffering life-changing injuries in his fight with Nigel Benn. Nigel Mansell was his neighbour. This is the tale of a man who has spent his life in close proximity to legends; he interviewed them, befriended them and shared their defining moments until he became part of the DNA of Britain's sporting history. Many of his interviews are still used in TV shows today. In his highly anticipated memoir, Newbon tells all. Encompassing a plethora of anecdotes that reveal the depth and wit of figures such as Brian Clough, Muhammad Ali, Billie Jean King and many others, this book considers how these people felt and thought during the pivotal sporting moments of the past half-century. From the Hand of God goal to the Munich massacre, Gary Newbon was there for it all. This, for the first time, is his story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 491

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

vThis is for the Newbon family past and present and all those who made my career possible.vi

Contents

Foreword

It seems as if I’ve known Gary Newbon for ever – it certainly feels like it! Some people think that if Gary was a bar of chocolate, he would eat himself, but there’s far more to this icon of sports broadcasting than meets the eye, and when you’ve read this book you will I’m sure agree that the man is a one-off.

I grew up mad on all sports and master of none of them, but throughout his career Gary has been involved in so much of the sporting world that he has become synonymous with many great memories and brilliant moments across a huge range of sports. His wicked sense of humour and fearless pursuit of pivotal moments live long in the memory, and somehow he became a major focal point in the crazy world of TV sport.

We crossed swords on numerous occasions. Some of those were difficult; for instance, when he refused to allow ITV to record an undercard fight featuring ‘Baby Jake’ Matlala, the world flyweight champion, because he had advertising on his trunks. He refused to budge despite a barrage of abuse from yours truly, but I did have the last laugh when the main event lasted less than one round and xITV hadn’t recorded the excellent title fight because of a 3in. x 2in. logo on his shorts!

But mostly we got on well in the mad world of sport, usually seeing the funny side of things, like when Chris Eubank’s opponent Ron Essett was in the ring while Chris was still in his dressing room, waiting for his trainer to finish a shower, or when I wouldn’t let Eubank in the ring after his entry music (‘Simply the Best’) was sabotaged. Newbon nearly had another stroke trying to keep to ITV’s transmission times. But that was Gary Newbon – dedicated to his employers (thirty-six years with ITV and fourteen with Sky) and desperate to air the very best show he could.

He has had a remarkable broadcasting life with some amazing episodes, most of which are captured in this book. I can assure readers that they are all more or less the truth and some have given me a chuckle, as I read about Gary getting into a right mess and somehow emerging with a smile on his face.

Sport is such an important part of our lives and it makes memories that live with us for ever. Gary has played his part and lived the life and in doing so has established himself as a true icon of broadcasting.

I am proud to know him as a friend and I hope I can maintain the level of enthusiasm he has shown for the past fifty years.

Enjoy his memories; they are guaranteed to leave you with a smile on your face.

Barry Hearn OBE

September 2023

Introduction

I laughed a lot while I was writing this book. I know you shouldn’t do that when you’re telling stories about yourself, so I hope you find them funny as well. They are all true tales. When I look back over my fifty years of TV sports presenting, I cannot believe some of the things I got up to and the events I got mixed up in. It is time to share them.

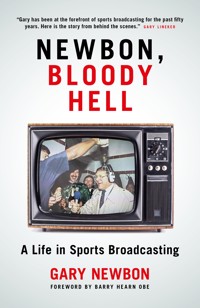

The title of my book might puzzle you. Why Newbon, Bloody Hell? It was inspired by my most famous interview, which was with Sir Alex Ferguson after Manchester United’s dramatic 2–1 European Champions League final win over Bayern Munich. Both United goals came in stoppage time when the game and treble trophy haul looked lost. On the final whistle, as he was struggling to take it all in, Sir Alex said to me, ‘Football, bloody hell.’ He then paused to recover and said, ‘But never give in!’ It was a golden time for broadcasting and newspapers and many of the strokes I needed to get ahead would not be acceptable today.

My opening chapters are about two successful football managers who played incredibly important roles in my career – Sir Alex Ferguson and Brian Clough. These were two of the sporting xiipersonalities that had the biggest impact on my career. The other two were boxer Chris Eubank and footballer-turned-TV-star Jimmy Greaves.

I will chart my journey from a £5-a-week apprentice journalist to years of a privileged and fulfilled life in television. I had disappointments along the way as well. During my thirty-six years with ITV and fourteen with Sky Sports, I experienced much to recall. Those years included seven World Cups, three Olympic Games and many football and boxing championships, both at home and around the world. I covered other sports too, including speedway, motorcycling, darts, snooker and greyhound racing.

My life was about covering and interviewing the biggest names in sport. Three times I interviewed Muhammad Ali. On seven occasions I interviewed Pelé. In fact, I was lucky enough to speak with a range of legends, including Carl Lewis, Mike Tyson, Lennox Lewis, Sir Garry Sobers, Sir Geoff Hurst, Jonah Lomu, Lord Coe, Lord Botham and so many others. There were many events and stories – the terrorist outrage at the Munich Olympics; sitting on Aston Villa’s substitute bench at a European Cup final. I was Clough’s minder the night he called Jan Tomaszewski a clown. One day I wondered about even including a young unknown Arnold Schwarzenegger on my TV show. Eventually I did show Arnie, but I refused to have my photo with him, telling everyone that they would never hear of him again. Oops!

One proud achievement was persuading the Queen Mother to let me make a documentary on Her Majesty’s interest in horse racing.

I once had to ask Sebastian Coe to run 600 yards to my car soon after he won an Olympic gold medal.

xiiiI have fond memories of helping an unknown neighbour on his way to becoming a Formula One world champion.

I have enjoyed a career that many people would have loved to experience. I am still working flat out – it is what I do – but I have reinvented myself in different roles. I will never retire. I love it too much. Sadly, there are close friends who I have shared great experiences with who are not here to read this book. I still mourn their passing. Friends like the first million-pound footballer Trevor Francis, who I first interviewed when he was fourteen years of age; veteran actor Roy Dotrice, a bundle of naughty fun who passed at ninety-four; and above all my wonderful parents, Jack and Preeva Newbon, and my much-loved younger brother, Ian.

Why have I written this book? By the time it is published, I will be heading towards seventy-nine. Moving up the bench of life! I hope you enjoy some of my memories and tales and can smile and laugh along the way. If so, it has been well worth the effort. xiv

Chapter One

The Charismatic Brian Clough

Two of my most famous interviews were with two successful football managers to whom I owe a lot. The first was Brian Clough, who kissed me in front of millions of ITV viewers after his team, Nottingham Forest, suffered a heavy defeat at Everton. The second was with Sir Alex Ferguson, at a moment in which he was almost shell-shocked after Manchester United scored two stoppage-time goals to beat Bayern Munich 2–1 to win the European Champions League, complete the treble and eventually reward Sir Alex with a knighthood. And he provided me with a famous quote! Alex came halfway down the long Nou Camp tunnel for me right on the final whistle and said: ‘Football, bloody hell,’ and after a pause added, ‘But you never give in!’ The second quote became the name of the documentary on his life, which was masterminded by his son, Jason. Memories of working with Sir Alex form the next chapter.

Back to Clough. Forest had just played badly at Goodison Park and lost 4–0. Trevor East, ITV’s head of sport, had told me that I 2had just thirty seconds at the end for the live interview as the players came off. It was a Wednesday night on 4 April 1990, and we were tight up in front of News at Ten. This was not a sports channel with hours to fill. Before the game I went to see Clough, who invited me into the Forest dressing room. I was asked what I wanted, so I said I needed a very tight interview with him at the end of the match. After asking ‘win, draw or lose?’ (I said: ‘Yes please’), Clough promised he would do it. Just before the final whistle, Trevor said to me: ‘Are you sure he’ll do it?’ I said I was positive. Clough was reliable and always kept his word.

What actually happened was Clough’s team were very poor, and Everton beat them convincingly. I tried to make it easy for Clough, suggesting that Forest had played badly because they had a League Cup final coming up. Clough replied, ‘Only Albert was sure of a place on the coach to Wembley.’ I challenged Clough: ‘You don’t have an Albert.’ Clough explained, ‘Yes we do, he’s the driver!’ That stung me, rather stupidly, and I upped the aggression in my line of questioning. As I kept pushing Clough, the manager realised I was going way over the thirty-second limit, and my floor manager Stan Harding was going berserk, until eventually Clough rescued me by saying: ‘Because our lot are a bunch of pansies like you and me!’ and promptly gave me a huge kiss!

It threw me completely! On the night, the tabloid sports editors sent their match reporters round to ask me if Clough was drunk, but I explained that he just loves me! I am told Northern comedians had a cruder version of events!

Clough is still talked about today and attracts the biggest laughs when I tell stories about him in after-dinner speeches. Personality-wise there has never been anyone like him in football. 3Liverpool’s Jürgen Klopp, with his lovely smile and energy, is the closest in the modern game. People often ask me who would be No. 1 on my interview list. That should be a difficult choice, knowing all those I have been able to talk to on television, and many have been very good, but the top of my list? Brian Clough. He was a remarkable man – egotistical, genius, arrogant, bombastic, outrageous, funny, quick but at times, perhaps in contrast, very kind. I was ‘on his patch’ (the Midlands) and he really looked after me with access, interviews and trust.

He certainly understood the media and how to make headlines. He knew what he was doing. I once knew the vague details of a story, and Clough could have told me the whole thing, but he didn’t want to. I asked him: ‘Would you tell me in confidence, Brian?’ He declined, saying: ‘If you do not use it now, then you may in ten years’ time.’ Another lesson for me. What Brian achieved at both Derby County and Nottingham Forest was simply remarkable. He was of course most effective as a football manager when he was partnered by Peter Taylor. Clough was the leader, bossy, powerful. Taylor was the spotter of talent and, at times, a calming influence on Brian’s excesses. They were to fall out over the financial spoils of their relationship and neither was effective in football managership on their own. Their breakup was such a shame.

But back to the many great days. Cloughie was brilliant but unpredictable to interview. But he would always attract a TV audience.

When I first came to Birmingham City in 1971 there was a big social club at the ground where you would see the likes of rock stars Jeff Lynne from Electric Light Orchestra or Roy Wood from the Move mixing with the other Blues fans drinking and talking pre-match. The lunchtime TV football shows on the BBC and ITV 4would be drowned out until someone yelled ‘Brian Clough is on the telly’, and you would then almost hear a pin drop. What was he going to say? Something outrageous? Who would he slag off? He was never dull; he certainly had it.

I started to interview him when the former England football captain Billy Wright became my boss at ATV, after signing me from Westward TV in Plymouth. The former Wolves and England captain was head of sport and outside broadcasts at the Birmingham-based TV centre. He was a lovely, modest man who never chose to remind you how famous he was at that time. But administration and appearing on TV to preview the Saturday games were certainly not his strength. On the latter, Billy struggled with words and names and regularly messed it up. The one thing I did not like Clough for was that the night before home matches he would assemble his players at the Midland Hotel in Derby, and part of the routine was to have a laugh at Billy. He deserved more respect. But, they had a point.

As much as I loved the man, I did eventually persuade the other bosses to keep Billy off the screen, apart from presenting awards and the like. Otherwise, Clough was great for me, providing regular interviews as Derby won the 1971–72 league title.

Clough and Taylor began their managerial partnership at Hartlepools United before moving to Derby County, where they soon took the Rams from the Second Division to winning the Football League title.

At the Baseball Ground stadium, Clough’s office was right next to the directors’ room – ironic, because he was soon to deeply dislike them. There was a long corridor from the manager’s office to the 5home dressing room. He had a phone connection to that dressing room from it. One rare day Clough was the only person in the stadium apart from the apprentices cleaning up in the dressing room. Clough suddenly rang down to the youngsters. He asked: ‘Do you know who this is, young man?’ One apprentice answered: ‘Yes. It’s the manager, Mr Clough.’ Clough replied: ‘Good lad, now I would like a pot of tea with some milk, plus some biscuits.’ Back came the question: ‘Mr Clough, do you know who this is speaking?’ The reply: ‘No.’ The young lad then exclaimed: ‘Then f*** off!’ Furious at this, the manager sprinted down the corridor, but the apprentices had all run out of the ground!

Clough, a regular pundit on ITV, was aware of London Weekend Television trying to keep me out of the loop at times, so he insisted that I did all the interviews ‘on our patch’ as he did when at Nottingham Forest. I will always be grateful for that, because it gave me invaluable network exposure; I was making my mark.

One of Cloughie’s main characteristics was that he was very outspoken. He verbally attacked Leeds United as a dirty team and clashed with their manager, Don Revie. The memory of these attacks did not serve him well when he eventually lasted just forty-four days at Elland Road.

It goes without saying that he was far more successful at Derby, where his title win landed the club a place in the European Cup. He had assembled an exciting team with players like Roy McFarland, Alan Hinton, Archie Gemmill, John O’Hare, Kevin Hector, his faithful captain John McGovern from Hartlepools and Colin Todd. Before I arrived in December 1971, he had made two inspired signings – Willie Carlin from Leicester and Dave Mackay from 6Spurs, and the Tottenham manager Bill Nicholson had asked Hayters Sports Agency to cover their end of the move. I was at Hayters at the time and was asked to do it.

Before he made the move to Derby, Mackay had been intending to return to Edinburgh and his boyhood club Heart of Midlothian, but one day Clough turned up at White Hart Lane to see Nicholson and said: ‘I have come here to sign Dave Mackay.’ This was an insight into how Clough and Taylor operated in those days: no nonsense. Incredibly, Clough persuaded Mackay to come to the Baseball Ground, and he went on to become such an influence on his teammates in the early days of Clough and Taylor’s tenure. Mackay led by example; he did not talk a lot but showed how to do it, and when he gave advice, every player listened. Carlin in midfield cajoled and pushed the players. The two of them were so important in the formative years of the Clough era.

Carlin in midfield would play in front of Mackay, so that any opponents would have to get past him before Dave, who would play at the back with McFarland. Roy in turn would face the opposing centre-forward.

Mackay was getting towards the end of his playing days and his last season was the first time, after a long and aggressive career, that he played a full league season.

Mackay was also a great leader, and McFarland says that he and the other players learned so much. Mackay used to tell them that they should try things and that they could do it.

I was to get close to Mackay in his managerial days. An easy man to deal with and a schoolboy hero of mine when I used to travel to Spurs from my Cambridge home during the school holidays.

With Mackay ready to go, Clough and Taylor set their sights 7on the nineteen-year-old Tranmere Rovers defender Roy McFarland, who was to captain Derby in their league championship year of 1971–72. McFarland was aware of Bill Shankly wanting him at Liverpool and, naturally, he was excited at that prospect. However, Clough and Taylor had other ideas. Taylor first saw McFarland in a season opener at Torquay, where Roy confirmed to me that he had a shocker against an experienced centre-forward. Taylor was to tell him later that he was attracted by McFarland’s unwavering effort and commitment. The next game was at home. Unknown to Roy, Clough and Taylor had already agreed terms with Tranmere.

After the match, McFarland and his cousin went for a post-match beer, and he got home at 11.15 p.m. He went straight to bed but was woken two hours later by his mother telling him that, absurdly, there were two men downstairs who wanted to talk to him. Those two men were Clough and Taylor. Dressed only in his pyjamas, Roy listened as they informed him, between sips of the tea that his mother had made them, that they were there to sign him. Roy, confused, turned to his dressing gown-clad father for advice, which he received in the form of: ‘Well, if they’re this keen, I’d join them.’

Roy asked them for the weekend to think about it, but in their classic, direct style, they said no. It had to be done there and then. Taylor slid the form over and sat next to Roy, telling him to take his father’s advice and sign, which he did. Tranmere played their home games on a Friday night so the next day, with his cousin, McFarland went to watch Liverpool win 5–0 at Anfield. Aghast, he turned to his cousin and exclaimed: ‘What have I done? I’ve just made the biggest mistake of my life!’ But if you asked him today, McFarland would tell you, as he did me, that it was not a mistake. It changed 8his football career for the best, with trophies and England caps to spare. And it was all down to Cloughie’s midnight visit.

Another of these stories is how Clough slept on Archie Gemmill’s sofa to make sure he signed him the next morning after ‘selling’ the midfielder the move to the Baseball Ground. That was then. I do not think Clough ever got to like the new world of football agents. My great friend Jon Holmes, the best in the business, had a rough experience at a meeting with Clough as Gary McAllister’s possible move to Nottingham Forest failed to happen. Clough was similar to Sir Alex Ferguson in that, besides being winners, they had time and kindness for many people. I was a recipient of that kindness from both of them. When Derby played Slovan Bratislava at home in their European Cup campaign, Clough showed the kind side of his nature.

It involved my father Jack, who, as a youngster, loved cricket and boxing but had little interest in football. However, like many of his generation, that changed when England won the 1966 World Cup. We were a Cambridge family. In the Second World War my father had survived forty operations in a Handley Page Hampden, the RAF’s slowest plane. It was so dangerous that only 8 per cent achieved that survival rate and they disbanded the model in the early 1940s. Ironically, I had first seen Clough in person playing in the stadium on the road I was raised: Milton Road, the home of non-league Cambridge City. He had taken part as a Sunderland player in the early ’60s in a testimonial for Norwich City manager Oscar Hold and was still in his playing gear when standing on a seat listening to the presentations in the social club. I was a City supporter and stood underneath him when he stood on a bench seat. I was too much in awe to ask for his autograph. A big thrill… 9Little was I to know that years later I would be interviewing him regularly while I worked for Billy Wright.

But anyway, back to this European match. I asked my dad if he would like to join me on the touchline, and he gladly accepted. Before the game, I introduced him to Brian. At the end, he beckoned in our direction: ‘Come with me to the dressing room.’ I moved forward. ‘No, not you – your father, Jack.’ They went into the Derby dressing room and I was left stranded for ages! I was soon looking at my watch, worried about running out of time before the highlights show in London. Cloughie had shown my dad around, introduced him to all the players and even asked him about the war and the family business that my parents built from scratch. He also explained the sayings on the wall: ‘The greatest crime in football is to give the ball away’ and ‘God did not invent grass to keep the ball in the air!’

Eventually they both emerged, to my relief. Clough said: ‘Jack, I now have to do some work with your son.’ And turning to me he observed: ‘By the way, Gary, I much prefer your father to you!’

Brilliant words. My dad, who was 5ft 7in, suddenly felt 6ft tall. I will always appreciate the way Clough treated him. Sadly though my dad, having survived the war, died from a heart attack when he was just sixty-two years old in 1982. I used to talk on the phone with him every day. I so miss him.

That Derby European Cup run ended in the semi-finals. They lost 3–1 in the first leg against Juventus in Turin. Archie Gemmill and Roy McFarland were booked – targeted because they were both on a yellow from a previous round and were therefore suspended for the return leg in Derby. It felt like the referee was against Derby all night.

10Our commentator Hugh Johns and I had been sent over to watch the game as we were covering the second leg. We were joined by my close friend Lorenzo Ferrari, who at the time ran the most famous Italian restaurant in Birmingham. Hugh, one of the greatest voices in the history of TV sport, thought I wanted his job, which I did not! We had adjoining rooms in the hotel and spent the night emptying the two mini-bars while I convinced him there was nothing to worry about. We bonded from then on, and I was honoured to give the eulogy at his funeral in Wales in the summer of 2007, after he died aged eighty-four.

Back to the Turin first leg tie. We joined Clough and Taylor outside the Derby dressing room after the match. They were raging, instructing Lorenzo to tell Juventus and the referee what ‘cheating bastards’ they were and worse. Lorenzo tells me he had to put a softer spin on it. The media travelled on the team plane and Clough, still upset at this new experience of cheating, spent most of the flight going up and down the gangway, pouring us all drinks.

The home match finished 0–0. The day before, we had visited Clough at the Baseball Ground in his office. Lorenzo had brought his great friend Giampiero Boniperti, a Juventus legend. He had played his entire career at Juventus from 1946 to 1961 and was now president of the Turin club. He did not speak English, so Lorenzo asked Clough if Boniperti could see the pitch. Clough, still angry, said: ‘No, tell him to f*** off.’ Lorenzo explained to his great Italian friend: ‘Mr Clough apologises, but he says it is not possible today as the groundsman is working on it and has locked the entrance.’

Clough learned a lot from that experience that was to stand him in good stead when he went on to win back-to-back European Cups with Forest. He took teams to four European semi-finals – two he 11won; the two he lost had seemingly biased referees. The other one was the 1983–84 UEFA Cup semi-final, when several highly debatable refereeing decisions went against Forest. It was later revealed that the referee, Guruceta Muro, had received a big ‘loan’ from the Anderlecht chairman, Constant Vanden Stock. When this emerged in 1997, Anderlecht were banned for one year from European competition. This was no consolation for Clough and Forest.

It ended badly for Clough and Taylor at Derby. The Derby chairman Sam Longson wanted Brian to cut down on his TV and newspaper writing commitments in London. Cloughie did not want to and the fallout began with the other directors encouraging the chairman to ‘cut back on’ Clough’s excesses. I was being fed exclusive updates. Clough was convinced it was the chairman or someone outside the club with a vested interest. Actually, it was a senior member of staff. Clough did not hold it against me as he knew I was just doing my job, but his subsequent dislike of the chairman and directors was born from his fallout with Longson. My recollection is that he was persuaded by a director that if both Taylor and himself resigned, it would be a double deal, in that they would be reinstated and Longson would go. But sadly their resignations were accepted and they were not reinstated. Clough was furious. He watched an interview I did with the chairman explaining the situation, and when I reached Clough for a comment he exclaimed: ‘You have just been talking to the reason!’ He then used his fingers, gun-like, to ‘fire’ at the camera. It all fell into place.

The players led demonstrations and protests, but to no avail. There was no return. In 1975 his former Derby captain Dave Mackay and his assistant Des Anderson led the Rams to another league title. But the decline eventually followed and recent seasons 12have been disappointing at their modern stadium, Pride Park. There is a statue at the new ground of Clough and Taylor; Derby history owes much to them. Taylor went to Brighton to be joined later by Clough, who then went solo for a disastrous forty-four days at Leeds where players like Billy Bremner, who had been insulted in Clough’s Derby days, never accepted him.

After Derby, Clough continued his work with ITV and for the vital 1974 World Cup qualifier against Poland at Wembley. I was Brian’s ITV minder and was instructed to keep him away from drinking. I failed! Clough found out about a BBC drinks party happening before the match in the Wembley Hotel, and we were soon invited in there. I thought Brian was fine when we arrived at the ITV gantry for live coverage, but what followed caused headlines and is often recalled in articles about him. He was part of ITV’s ‘pundits’ panel’ at Wembley. We got there in good time.

The Polish goalkeeper was Jan Tomaszewski, and he stood between England and the win they needed that night to qualify for the 1974 World Cup. He made a series of vital saves that limited England to the 1–1 draw. Poland went on to finish third in those finals and he went on to be named best goalkeeper. He also played a crucial role when Poland won the silver medal at the 1976 Olympics. However, on the night of the game at Wembley, Clough described Tomaszewski as a ‘clown’! He couldn’t have been more wrong! Both Clough and Tomaszewski made a huge impact that night, for contrasting reasons.

After ITV came off air, we both walked up and down the pitch, the stadium now deserted. We were desperately disappointed that England would not be in West Germany. He never got the England job. Some at the Football Association seemingly felt they could not 13handle him. When Taylor and Clough had earlier been in charge of the youth players at an overseas tournament, they had waited some while on the team coach after the match before Clough ordered the driver to go and left the FA party stranded! It was criminal that Clough and Taylor never got the job and, despite two semi-finals and quarter-finals England have yet to win the World Cup again. Maybe Gareth Southgate will change that.

After that Wembley night with the Polish draw, I lost touch with Clough for a while (apart from interviewing him in a Solihull music venue). During that time, he was briefly at Brighton and Leeds. But he bounced back to the big time with Nottingham Forest from 1975 to 1993, and when Clough was reunited with his outstanding assistant Peter Taylor, the trophies began to flow. Let me get the major ones out of the way: First Division title 1978; European Cup 1979 and 1980. Four Football League Cups: 1978, ’79, ’89 and ’90. Unfortunately, they never won the FA Cup, despite reaching the final in 1991, but Clough was awarded Football Manager of the Year 1978 and an OBE for his services to football in 1991. (Clough described it as ‘other buggers’ efforts’.)

When we think of successful footballing managers, the likes of Bob Paisley at Liverpool, Sir Alex Ferguson at Manchester United and Pep Guardiola at Manchester City come to mind. But these managers were working with big English clubs. Clough and Taylor achieved their success at Derby County and Nottingham Forest, who, with respect, were hardly huge clubs. At Derby, Clough and Taylor took the team back to the First Division, which they won. With Forest, they won the Football League title in 1978 after being promoted from the Second Division the previous year, and they then immediately won back-to-back European Cup trophies. That 14achievement was quite staggering and will probably never be repeated by a club the size of Forest. Clough was the abrasive leader who, when attempting to sign good players, would say to them: ‘Show me your medals,’ knowing of course that they had none of note. Taylor was the steadying influence and a fine judge of player. His son-in-law, John Dickinson, worked with me at ATV and then Central TV. I remember John telling me that he went with Peter to watch a prospective signing at Cambridge United. They left after two minutes with Taylor saying: ‘He can’t play… Not for us!’

Not that it was always sweetness and light for me.

One Saturday around 1980, I woke up on a Saturday having lost my voice. Katie told me that I couldn’t possible go to work and do my Star Soccer show (highlights of some of the Midlands Saturday-afternoon matches). I told her that I was not letting anyone else do it! The first person I bumped into at the City Ground was Clough, who said: ‘Morning.’ I could hardly croak a reply and was asked what my problem was. When I told him that I had lost my voice, he said: ‘Two and a half million people in the Midlands will be absolutely thrilled with that news.’ And he promptly walked away! But he did later send the club doctor round to dose me up.

In the mid-’70s, I had formed the Midlands Soccer Writers club, which was based at Lorenzo’s restaurant in Birmingham. As it developed, I persuaded my ATV bosses to let me stage the Midlands Player and Young Player of the Season Awards. We used one of our studios to put on a dinner jacket show with the media, managers, players and public figures like Jasper Carrott.

Clough did the honours in the second year, with Trevor Francis of Birmingham City winning the Young Player Award. When Trevor joined us on the stage, he had his hands in his pockets. 15Clough said: ‘You are a very talented young man. Now, if you would kindly take your hands out of your pockets, I will present you with this trophy!’ Another Clough moment to remember! Mind you, we had to stop Trevor’s manager Willie Bell sticking one on Clough in the bar afterwards! Willie, normally a lovely man, was very religious, so that was out of character for him. Sadly he died in 2023 in the USA from a stroke, aged eighty-five. As did lovely Trevor from a heart attack, aged just sixty-nine.

Much later of course Clough made Trevor the first million-pound footballer, and he went on to score the only goal in the European Cup final. I did a TV interview with Trevor when he was aged fourteen in Plymouth. He was the star of the Plymouth schools and was being watched by all the leading scouts. I was twenty-three and had just got my first job in TV with Westward TV. I do not know who was more nervous!

I followed Trevor to Birmingham. He had signed his Blues contract on the desk of my future wife, Katie, in the ATV newsroom. I was to join ATV later. Trevor split his time between his homes in Solihull, where I live, and Spain. We were close friends with regular phone calls and meetings when he was in Solihull. Like so many I was shocked and saddened by his death. Trevor was a lovely, approachable man who was very private. He was lost for a long while after his wife Helen passed away following a long and brave battle with cancer. He was a private man with a limited circle of friends at his own choice. I was lucky to be included.

I was at the Munich final as an observer for Trevor’s finest moment. Trevor told me about the bizarre events the night before the game. Clough and Taylor called the players to a team meeting in their hotel. The squad assumed it was to tell them the team. No 16such luck. Indeed, they were not to know until well into the following morning. Clough kept ordering copious amounts of German wine. At one stage Archie Gemmill stood up, only to be asked by Clough where he was going. Gemmill explained he was heading for bed. ‘No, you are not,’ ordered Clough. ‘Sit down!’ Trevor told me that two of the selected team needed pills from the physio on the morning of the final after suffering slight hangovers. Clough was certainly unconventional.

Before Forest’s European success, my ATV producer Trevor East had the idea of pairing Clough and myself once a month live in the studio on a Friday. Trevor went to see Clough and said it would be like David and Goliath. Brian said he would love it. Trevor asked him how much he wanted: ‘Trevor, I want as much as I can get.’ Point taken. The programmes were worth every penny.

Around that time, I was also told I had £7,000 spare on budget and to make a cheap series. I found seven highlights of the best matches of the ’70s and ’80s and offered Clough £5,000 to shoot a series with me in one afternoon called Cloughie’s Golden Oldies, in which we looked back on the games. We did it in the Forest trophy room. He never saw any of them, but I briefed him about the games before every take. He was simply brilliant, producing lines like: ‘I gave Coventry a million pounds for Ian Wallace and it is a testament to my ability as a manager that I did not get the sack for that signing.’ But his pay-off line was the best. I thanked him at the end of the last ‘programme’, and he turned to the camera and commented: ‘The biggest bouquet should go to the cameraman for managing to get both your head and mine in the same shot.’ There will never be another like him.

There were some outrageous stories in those European runs too 17– particularly the first one, in 1979. The European Cup was expanded and Forest drew Liverpool, with all their big players, in the first round. It was a sign of things to come when Forest won their home leg 2–0 and drew 0–0 in the second leg.

Next up were AEK Athens, with the away leg first. When we arrived in the Greek capital, the home supporters stoned the Forest team bus. Glass flew everywhere. Clough, understandably, was very angry. At the mandatory press conference the next day, a Greek journalist revealed they had discovered that Forest were offering their players a smaller bonus to beat AEK than they did to beat Liverpool: ‘Why is this?’ Clough’s reply: ‘So we can pay the referee as much as your cheating bastards will.’ Thanks, Brian. Being unpredictable, he then invited the Greek media to join us all for lunch. One other Greek reporter asked if he might interview Forest’s star goalkeeper, Peter Shilton. Clough’s response: ‘As long as you promise not to ram his fingers in the lift on the way down.’ Thanks again, Brian. Forest won the match, and on the terraces behind our post-match interview burned a range of small, controlled fires. Brian: ‘They are lighting fires in my honour.’ I decided not to correct him by mentioning that was how they burned all the rubbish left by the spectators out there.

Moving on to the semi-final. Forest play Cologne in the home leg. It finishes 3–3 with the headlines that a Japanese sub has sunk Forest: Yasuhiko Okudera scored in the eighty-first minute. ITV covered this match, and I really thought that the three away goals would be enough to knock out Forest for the away leg. At the end of the post-match interview, I put that to Clough, who said: ‘I hope no one will be stupid enough to write us off.’

Taylor asked me to place a bet on Forest winning the away leg. 18I got 7/2 for Forest to win, so Ladbrokes were agreeing with me. So, the match. Ian Bowyer scored the only goal. Peter Shilton made a wonderful save. Afterwards I put my head around the Forest dressing room door (those were the days) and Taylor asked: ‘Did you get on [the bet with Ladbrokes]?!’ I told him yes, and he was pleased. He then said that Brian was on the pitch. He was in fact walking around the running track outside the pitch, on his own in the now-deserted stadium. He beckoned me over. Putting his arm through mine, he said: ‘After the 3–3 home leg, when I told you I hoped no one would be stupid enough to write us off, you dropped your microphone and Brian Moore in London fell off his studio stool. Now you both know what I was talking about. I’ll see you at the airport.’

There were just a handful of trusted media in those days. Clough would give the press interviews, wonderful ones for both TV and the radio. Headlines all the way. Then he would say: ‘Right, put your pens and microphones away; we’re going out for a drink.’ And we did. Everything else just finished for the day. Sadly those golden days are over! The arrival of social media, mobile phone cameras, mass media and 24-hour rolling news has brought a different world, one with little trust.

So, to the first European final. There was big disappointment for Archie Gemmill and Martin O’Neill, who were both returning from injury and therefore failed to make the team.

Martin is one of the cleverest players I have known, and one of the funniest. He was a law student in Northern Ireland who gave it up for football. He has always been a brilliant speaker. He was probably too clever for Cloughie, even though Martin still loves to talk about him; he recalls Cloughie with some affection. In one 19interview Clough told me: ‘John this and Archie this, but our No. 7 [O’Neill] may not be as clever as he thinks.’

I was present on a stage when O’Neill talked about a long stint in the reserve team; he said that he asked Clough about it. ‘Why do you keep playing me in the second team?’ Reply: ‘Simple answer, Martin – I don’t have a third team.’ Genius!

But there was a soft side to Clough. On 2 February 2002, I suffered a stroke soon after leaving the Lowry Hotel in Manchester on my way to Old Trafford, to cover United. More on that in another chapter. I made a full recovery, but when I got home a week later, one of the many letters waiting for me was from Brian. He had simply written: ‘Get well soon. We love you – Brian and Barbara.’ I will always treasure that. Clough had a big heart for people in trouble and a full-throated commitment to the causes he believed in, like the Labour Party. He was a lifelong socialist. He also turned up to support the miners on their picket lines, as well as donating money to the trade unions.

But it was not always sweetness and light. Clough had a lengthy struggle with the demon drink, which affected him and the club. Years earlier he had fallen out with Taylor over the spoils of money. Taylor had left Forest to go back to Derby and, unknown to Clough, who was on holiday at the time, signed John Robertson. They never spoke again.

I went to Taylor’s funeral in 1990 and Clough and his wife entered the church at the very last moment. We were pleased about that. I think Brian, a decent man under it all, was full of regret. Brian stopped drinking eventually when he needed a transplant. He recovered and one lovely summer’s day I invited Brian and Barbara to lunch at their favourite spot, the Dovecliff Hotel near Burton 20on Trent. No cameras, no notebook, no agenda apart from an opportunity to thank them both for their support and kindness. We spent three memorable and happy hours there, including one final story from Barbara: when Brian was in a northern hospital waiting for the transplant, he was woken very early by the loud noise of a helicopter landing outside his room. He called for the surgeon and gave him a right telling off until he was told: ‘Brian, that helicopter has brought your new organ.’ Brian gave me a sheepish grin – I had seen his smile many times, but I’d never seen that embarrassed look! I never saw him again. He died in the Royal Derby Hospital on 20 September 2004, aged sixty-nine. His wife Barbara died on 20 July 2013, aged seventy-five.

There was one more involvement with Brian Clough for me. The unveiling of his statue took place just off Nottingham’s Old Market Square on 6 November 2008. I was not planning to go, as I was hosting back-to-back TV shows that finished at midnight. Sky had booked me into a nearby hotel. But the night before the unveiling, I had a call from a former member of my Central TV sports team, Keith Daniell, who told me that Barbara Clough was not happy with the person hosting the public address and had told Keith that Brian would have wanted me to do it. So, I got to Nottingham early with a faxed script ready for rehearsal. All set to go. The actual event was going well for me until I interviewed Councillor John Davies, the leader of Nottingham Council. ‘So,’ I asked, ‘what did Brian Clough really mean to the city of Birmingham?’

I didn’t even realise what I’d said until 4,000 people started booing. Anyway, I corrected and composed myself and off we went again without another hitch. Afterwards lots of people said ‘well done’, but I knew the media would pick up on my major error. I 21have always got on with them and they were kind in their comments! However, two days later Ron Atkinson, who was always doing quizzes and ringing me for answers, was on the phone. ‘Hallo, pal, quiz question: what is the capital of Peru?’ Quick as a flash, I replied: ‘Lima.’ Ron then quipped (before putting down the phone): ‘How come you know that, but you don’t know where Nottingham is?!’ Brian Clough would have enjoyed that!

Chapter Two

Sir Alex Ferguson – The Boss

The first time I interviewed Sir Alex Ferguson I fell out with him, although I did not realise it at the time! I interviewed him at the end of a match at Old Trafford, and I asked him about getting the sack. He gave me a sort of brush off. There were rumours at the time that he was under early pressure at Manchester United with suggestions that he was facing the sack. It is often said that the goal by Mark Robins that gave United victory in the FA Cup at Nottingham Forest saved Sir Alex, but that has never been proved.

Anyway, a few weeks after my first short interview, ITV’s live match was Norwich vs Manchester United. I was, as usual, doing the interviews, so I checked with Sir Alex: ‘OK for a quick interview afterwards, please?’ ‘No,’ came the reply.

This had never happened before. I thought I had good relations with everyone, so I asked: ‘Why not?’ The reply: ‘Because, you ask crap questions.’ A little stunned, I enquired: ‘May I at least talk to the players, then?’ To the manager’s credit he did not ban me completely, saying: ‘You can talk to anyone but me.’ So I thought, 23what do I do now? Was Sir Alex being fair? I normally hate that journalistic justification – ‘I was just doing my job.’ Realising that I might have pushed him a bit far with my sacking question, I decided that I should have warned Sir Alex beforehand. I could see his point of view. But what was I to do about it? This was not a boxer I was dealing with, an athlete of whom I could ask some pretty direct questions.

Manchester United have always attracted TV’s highest ratings over the years, but they were not featuring so much on ITV then – around 1986. There therefore wasn’t going to be much opportunity to help him set the record straight, since I would not be in a position to ask him questions if we were not covering a United match. Even so, I wanted to make it up. Trust has always been an important factor in my career. Without realising it, on that first interview I had broken Sir Alex Ferguson’s trust. I was not angry with him at Norwich. I was disappointed that I had put myself in that position.

In those days, newspaper journalists often accused TV interviewers of being soft with their questions. But the writers always swapped quotes and stories if one of their kind had been banned, therefore covering one another’s backs. With TV you have to get the manager or player in front of a camera. News reporters hardly ever see their subjects again, apart from politicians, who have thick skins and for whom the banter is part of their lives. But sport is different. Emotions run high and people can become riled. I was not dealing with Brian Clough here. As luck would have it, however, an opportunity presented itself a few weeks later. I had covered boxing for the regular series Fight Night in Manchester and was staying at the Midland Hotel. When I went for breakfast the next day, I was surprised to see Ferguson sitting on his own. ‘May 24I join you, please?’ I enquired. To my relief, he nodded. I sat down with my buffet breakfast and asked Sir Alex: ‘May I start again?’ To which he asked: ‘How?’ I promised that, from now on, if I had what I described as a ‘curveball question’, he would know about it before any interviews. I tried to assure him that he could really trust me. He agreed and it began what I considered a really good relationship built on trust. I know I must have irritated him at times with my requests, but he always accommodated me, including by doing live half-time interviews in European Cup matches. I have always believed you have to take people as you find them – not as other people would have you believe.

I have heard some journalists’ negative opinions about Sir Alex, but they only hold those because they have been banned from interviewing him. They should give him credit that those bans were lifted! Journalists and newspapers, as well as football managers, can be sensitive souls at times – they reserve the right to dish it out, but they are not too good at taking it. Sir Alex had to be very tough and ruthless at times. But he had to be fair with us as well, and with his players, as long as they gave him 100 per cent on both the field and the training ground. He would not tolerate idleness and was a stickler for making sure his players trained like they played. He once told me that if any player challenged his authority as manager, they would have to go – and they did. I realised how important that principle was, and it was an important factor that I took into my twenty-two years as controller of sport at Central TV, which in that time was a major player in both national and regional sport.

He also handled the media with, at times, an iron fist. He fiercely protected his players and the club, particularly against criticism. The big difference between the Clough and Ferguson days 25in England was the sheer expansion and volume of the media. In Cloughie’s early days, there were usually about twelve trusted football reporters. Local and national press, TV and radio and agencies. Broadcasters and reporters had to come back time and again to basically the same football people. Then we had the introduction of the news reporters, the rolling TV news, the overseas media, the online media and eventually social media. Sir Alex, for instance, did not know a lot of them. He wondered what their motives were. What was the agenda? He had to be cautious when packed press/media conferences took place. At times, he would rather they not report on United, as they would often be highly critical. The media were thirsty to dish it out and then puzzled when they did not get what they wanted from the manager. I never asked questions at news conferences. That was not my brief. Some of the questions then and now strike me as overladen with the interviewer’s personal opinions and observations. Since the object of the exercise surely is to get your subject’s opinions, it seems absurd for interviewers to make it so aggressively about themselves.

Moving on from that, I want to write about the compassionate side to the man. As previously mentioned, on 2 February 2002 I suffered a stroke while in the Lowry Hotel in Manchester on the morning of a United–Sunderland match, for which I was scheduled to do the interviews. I was one month from being fifty-seven years old. But suffice to say I recovered, and Sir Alex was on the phone three times when I got home checking on my recovery. As I write this I have reached seventy-eight and am still going! Then in 2010, while my wife Katie was suffering from a deadly malignant melanoma, she discovered that she also had a large brain tumour. Sir Alex had been told this by our old floor manager Stan 26Harding (whom Sir Alex was also fond of) as he was leaving their Birmingham hotel for the match at West Bromwich Albion. Sir Alex rang me from the team coach wanting to know all about it and wishing Katie well. My wife, against the odds, recovered, and although she is not into football, she really appreciated his concern. I am pleased to say that Katie, too, has made a great recovery. We will always appreciate Sir Alex’s concern and kindness.

There are other examples too. Joe Melling was a Daily Express football reporter who I knew well. Sir Alex and Joe did not get on very well, but when Sir Alex was told that Joe, a heavy smoker, had lung cancer, he rang him and said: ‘Joe, you fight this cancer as hard as you fought me!’

Bryan Robson, one of his great players and captains, developed throat cancer and received the usual caring approach from his old manager. Thankfully, at the time of writing Bryan is now eleven years clear and, like Sir Alex, a United ambassador. It is little known that, if at all possible, Sir Alex would go to the funerals of friends and people he had known well both north and south of the border. He always wanted to pay his respects. I attended two of those funerals – Paul Doherty (former head of sport at Granada TV) and Bob Patience, who had been the interviewer when Sir Alex won the European Cup Winners’ Cup final for Aberdeen against Real Madrid in Gothenburg. Bob moved to London Weekend Television and produced the Saint & Greavsie show. The funeral was in Basingstoke and the reception at the Wentworth Golf Club. The United manager made both venues. Football management is a cutthroat business. There is a relentless need to win matches and never-ending stream of out-of-work hopefuls waiting to take sacked managers’ posts. But there is care as well. When a manager lost his 27job, Sir Alex would often invite that person to spend time at the United training ground – in latter years, at Carrington. Those that went never forgot his kindness. He is loyal to his friends and many others, including his former players.

Then in May 2018 Sir Alex suffered a form of brain haemorrhage, which required emergency surgery. It was such a relief for family, friends, former players, the club, supporters and admirers to see him recover so successfully. Obviously I had nothing to do with his success story, but it was a satisfying experience to be interviewing Sir Alex on such a regular basis. I have a few other memories to share.

His predecessor Ron Atkinson had won two FA Cups but dipped out on winning the holy grail at the time – the Football League title. United as mentioned had been waiting since 1967 when they were last league champions under Sir Matt Busby. Sir Alex had become Manchester United manager in 1986 and after a shaky start began to hunt down the holy grail. They finally won the new Premier League in 1993. But there was immense disappointment the previous 1991–92 season when Leeds just pipped United. United went to Liverpool for their league game on 26 April having led the table for most of the season. They needed to win but lost 2–0 to goals by Ian Rush and Mark Walters. It meant that Leeds, watching at home, had won the title under manager Howard Wilkinson. I was doing the interviews for ITV’s live coverage at Anfield. Unlike the future sports channels we were tight for time at the end of the match. I was under pressure to get a reaction from Sir Alex and (as you could in those days) was with my cameraman right outside the away dressing room. After a couple of requests and my knocking on the door in desperation, Alex came out and, choked as he was, 28gave me the interview. He may or may not recall that, but I will never forget it and will never lose the huge respect I have for him for doing it.