11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

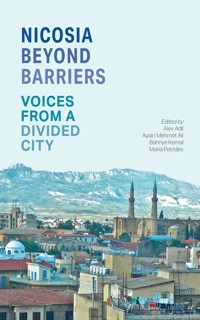

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Cyprus' capital Nicosia has been split by a militarised border for decades. In this collection, writers from all sides of the divide reimagine the past, present and future of their city. Here, Cypriot-Greeks coexist alongside Cypriot-Turks, the north with the south, town with countryside, dominant voices with the marginalised. This is a city of endless possibilities - a place where an anthropologist from London and a talkative Marxist are hunted by a gunman in the Forbidden zone; where a romance between two aspiring Tango dancers falls victim to Nicosia's time difference; and where an artist finds his workplace on a rooftop, where he paints a horizon disturbed only by birds. Together, these writers journey beyond the beaten track creating a complete picture of Nicosia, the world's last divided capital city, that defies barriers of all kinds.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

NICOSIA BEYOND BARRIERS

SAQI BOOKS26 Westbourne GroveLondon W2 5RHwww.saqibooks.com

Published 2019 by Saqi Books

Copyright © Alev Adil, Aydın Mehmet Ali, Bahriye Kemal, Maria Petrides, 2019Copyright for individual texts rests with the contributors.

Alev Adil, Aydın Mehmet Ali, Bahriye Kemal, Maria Petrideshave asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs andPatents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of tradeor otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without thepublisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that inwhich it is published and without a similar condition including thiscondition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 0 86356 674 5eISBN 978 0 86356 305 8

Cover image © Alev Adil

A full cip record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound by Clays S.A.r, Elcograf

This publication has been supported by Commonwealth Writers,the cultural initiative of the Commonwealth Foundation.

CONTENTS

Introduction by Bahriye Kemal

Erato Ioannou, Painting in the Wall

Anthie Zachariadou, Nicosia – Whispers of the Past

Aydın Mehmet Ali, My Accordion Teacher

Shereen Pandit, Divided Cities and Black Holes

Adrian Woolrich-Burt, Flaş

Andriana Ierodiaconou, The Heart of Nicosia

Nora Nadjarian, Exhibition

Constantia Soteriou, Red Lefkoşa Dreams

Jenan Selçuk, To Bastejkalna Park

Stavros Stavrou Karayanni, Gardening Desire

Lisa Majaj, Ghost Whispers at the Armenian Cemetery, Nicosia

Despina Michaelidou, My Name Is Queer

Haji Mike, The Photo – The Guard Post

Dinda Fass, Darkroom Delay

Dinda Fass, Calliope

Bahir Laattoe, Alif … Baa … Taa …

Hakan Djuma, The Missing Hour

Antoine Cassar, Leaving Nicosia, Part Six (from Time Zones)

Zoe Piponides, High Five

Argyro Nicolaou, A Waste of Time

Jacqueline Jondot, Why Are Green Lines Called Green?

Maria Kitromilidou, Beyond Barriers

Sherry Charlton, Nicosia Through the Eyes of a Child

Salamis Aysegul Sentug, Petrichor Requiem

Rachael Pettus, Ledra Street Crossing

Elisa Bosio, Blue Ants, Red Ants

Marianna Foka, First Call

Stephanos Stephanides, Broken Heart

Yiannis Papadakis, The Story of the Dead Zone

Kivanc Houssein, A Walk through Ledra

Dize Kükrer, The Endless Day

Norbert Bugeja, Ledra

Yiannis Papadakis, The Language of the Dead Zone

Gür Genç, Nicosia

Zoe Piponides, Hot City Dream

Maria Petrides, Coccinella, or Beyond Data

Christos Tsiailis, Knit

Marilena Zackheos, Within the Walls

Münevver Özgür Özersay, Buzzing Bees in My House

Anthony Anaxagorou, Two Syllables, Six Letters

Melissa Hekkers, Island in the Sun

Shola Balogun, I Too Shall Anoint the Stones

Tinashe Mushakavanhu, Nicosia’s African Diaspora

Caroline Rooney, Serendipity

Caroline Rooney, Outer Sanctum

Bahriye Kemal, Spatial Tripling-Triad

Sevina Floridou, Small Stories of Long Duration

Stephanos Stephanides, Rhapsody on the Dragoman

Christodoulos Moisa, Right Hand Corner

Jenan Selçuk, I Made A Promise to Blue

Rachael Pettus, Nicosia

Angus Reid, In the Company of Birds

Laila Sumpton, Nursery Tales

Alev Adil, Fragments from An Architecture of Forgetting

Diomedes Koufteros, Standing in Front of the Ledra Palace

Mary Anne Zammit, Shades of a City

Glossary

About the Editors

About the Contributors

Acknowledgements

Credits

INTRODUCTION

By Bahriye Kemal

At the crossroads of the world between west and east or north and south, Cyprus is a strategically located Mediterranean island that has had a distinct experience of major world events. It was once a transit site for Western pilgrims en route to the holy land, later an essential passageway towards conquest for Western and non-Western imperial regimes, more recently a key site associated with the Arab uprisings, with Islamic State activity and mass migration. The island has been subject to a cultural and political history of colonisation, partition and conflicting identities. At the centre of this make-up stands Nicosia, the world’s last divided city.

This anthology aims to bring writers and poets together in a single volume that captures Nicosia as a shared and contested site, with dominant and marginalised narratives, capturing its fragments and its unities. The forty-nine contributors – well-known and lesser known writers and poets, as well as emerging voices – come from a variety of backgrounds. Some are from or now live in Cyprus, others are visitors who have been inspired by the island in general and Nicosia in particular. All have worked, performed, walked, written and lived through Nicosia. This anthology captures a new way of reading and writing not only about Nicosia, but also other cities that have been marred by colonialism, conflict and division. This anthology is a dynamic, all-inclusive platform open to diverse voices, which come together to use literature as a tool to capture solidarity and celebrate difference in the Mediterranean capital city of Cyprus. It is writing that freely travels through the world’s last divided capital, bringing together strangers to create a new narrative of a city beyond all borders, boundaries, binaries, barriers.

ON HISTORICAL-POLITICAL NICOSIA, ΛΕϒΚΩΣΙΑ, LEFKOŞA:, LEFKOŞA: NAME GAME

This capital city has been a host to so many names throughout the ages. All the names of these different stages of the city’s time-line will be voiced in this book. You will encounter various different names used for the same people and places, and here I will briefly explain the reasons through what I call the ‘name game’. The name game is a core motif in cases of postcolonial partition – especially in former British colonies like Cyprus, Israel-Palestine, Ireland, India – that is commonly adopted by inhabitants of divided cities. This is a historical-political name game related to ‘identity’, most often based on ethnic, religious and/or national naming that divides groups of people into homogenous units. In these partitioned cases names consistently change when self and spatial conceptions change. In Cyprus this change operates as a site of contestation within and between ‘Turkish and Greek’, the dominant right-wing nationalist identifications that ideologically divides the people and places, and ‘Cypriot’, an emergent left-wing identification with a ‘structure of feeling’ towards uniting the people and places, ending in the adoption of ‘Turkish-Cypriot’ and ‘Greek-Cypriot’ as standard official names. In this book the preferred usage for the people of Cyprus would be ‘cypriot’, or to do away with binary names, however the contributors use binaries for clarification purposes. Here, you will encounter various different names for the people of Cyprus, including Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot, cypriotturkish and cypriotgreek, T/Cypriot and G/Cypriot. You will also encounter various different names for the same places, the most obvious to begin with being Nicosia (English), Λευκωσία/Lefkosia (Greek), Lefkoşa/Lefkosha (Turkish). In this way the book highlights and exposes the name game by showing that those of us who have felt partition, pain and wars are urged to play with and against naming conventions.

Thus in solidarity with the greatest philosophers and cultural theorists of our time, including Jacques Derrida, Paul Gilroy, Stuart Hall, Edward Said and Raymond Williams, who concern themselves with the name game as related to ‘identity’, this process reveals the following: an absolute rejection and weariness concerning the use of proper names for people and places; the farce of using a fixed, reified name for ‘identity’ (farcical because ‘identity’ is fluid); and the foolishness of notions like ‘problem of identity’ (foolish because ‘identity’ is not resolvable). There is no such thing as identity with a single name, there is only identification with multiple names. Identifications cannot and must not be considered via proper names because they lead to improper circumstances: it is those imaginings that prioritise ethnic identification over being an islander, or that prioritise identity to make it the higher, proper or uppercase, that have been the central culprits for the legacy of bloody binary contests and conflict in cases of partition. In this way the book captures and celebrates multiple different names for the city and its people that are always in production, so as to move beyond binaries and barriers.

This name game has been strengthened because of Cyprus’s strategic position between the geo-political world divide, where it has repeatedly been at the mercy of various ruling regimes who have changed the name to assume ownership of the city, the island and its inhabitants. The Venetians built the city’s walls with their 11-pointed bastions from 1489 onwards; the Ottomans took it in 1570 after posting their flag that transformed the city with new names; the British re-named it in 1878 via Herbert Kitchener’s first comprehensive British-Cyprus map. By 1950-1960s the inhabitants sought to rename and reclaim their city, when the anticolonial campaign with competing moves mapped a Greece-Cyprus or Turkey-Cyprus. This paved the way for independence in 1960, when inter-ethnic conflict reigned. The ‘Green Line’ Agreement, when General Young drew the green ceasefire line that partitioned the city and its people in two, was drawn up on 30 December 1963 between Greece, Turkey and Britain. On 20 July 1974 Cyprus’s geographical borders were reconstructed by Turkey through an extension of the Green Line that partitioned the people into ethnically homogeneous units, with the cypriotgreeks transferred to the south, and cypriotturks to the north. The borders then remained closed until Annan Plan V, a United Nations proposal that sought a resolution of the conflict before Cyprus’s accession into the European Union. This resulted in the opening of the borders in 2003, with the intention to build up relationships in preparation for the referendum. There was no resolution. Cyprus today has the world’s only divided capital with the south a recognised European state inhabited mostly by people who speak Greek, and the north a de facto entity mostly with Turkish speakers. Because of this spatiality, Cyprus is simultaneously at the centre and periphery of various positions that disturb fixed categorizations, thus serving to blur the dominant geo-political binaries within the city, the island and the world.

This spatiality is most prominent in the capital city, where it mostly operates through a dominant historical-political competing narrative between the cypriotgreeks and cypriotturks that generated the deadlock, which has come to be called the ‘Cyprus problem’. This spatial history also operates via marginalised narratives, especially the literatures of Cyprus, so the literary Other that is largely excluded in a national and international domain, yet that must be selected as the preferred means to write and read the divided city, because it captures solidarity to create a differential island and city beyond all deadlocks and barriers.

LITERARY NICOSIA, ΛΕϒΚΩΣΙΑ, LEFKOŞA

The island and its city have always been a host for differential inspiration for the inhabitants, visitors and exiles who come here. It has created people and been created by people, triggering the act for all of us to write, read and construct it regardless of who we are, where we come from, or where we are going. In writing, reading and constructing the city we understand what it means to be at the crossroad of the world, fractured, to be postcolonial, European but not quite, Islanders, to be Muslim but not quite, to be Mediterranean, to be divided, to be united, to suffer in pain and longing together in solidarity. In this way we understand what it is to feel, live and create a city and be created by a city – a literary-lived Nicosia, Λευκωσία, Lefkoşa – that is host to total difference and diversity. To understand the overwhelming importance of the writings in this anthology, it is very important to consider the broad scope of writings about the city and the island that are not in this anthology. We must address the literatures of Cyprus within a colonial, postcolonial and partition framework, unpicking the official and dominant, as well as the unofficial and marginalised voices from the city. This will demonstrate the move from official nationalist writings that are exclusive, homogenous and/or hostile, towards the marginalised and unofficial writings that are inclusive and that celebrate the diversity and differences of the city. In this book there is a dynamic dialogue where these writers negotiate with the official nationalist and unofficial marginalised writings related to the island and its city that have gone before them.

To understand these writings, first it is important to mention that the divided island and its city are predominantly discussed in political and historical narratives, and the literary narratives are largely excluded. In more official contexts, the literatures of Cyprus are ethnically and linguistically divided as either Greek by cypriotgreeks or Turkish by cypriotturks. Through a comprehensive survey of the literatures, however, I argue that the literatures of Cyprus include writings in Greek, Turkish, English, Arabic and beyond by Cypriots – cypriotarmenians, cypriotmaronites, cypriotgreeks, cypriotturks – as well as by Greeks, Turks, Brits and others. These are simultaneously exclusive nationalist and inclusive transnational literatures; they are Cypriot literatures positioned between Greek, Turkish and English literatures, so multilingual, uncanonised and minor literatures between major literatures. I call them colonial and postcolonial diasporic writings operating within and through displacement. This is writing made up of various literary forms that focus on moving around and narrating the city and the island so as to narrate the self. This is writing about places, spaces and identification, which responds to the cultural and political history of colonialism, postcolonialism and partition-moments detrimental to the city and the island.

During the anti-colonial moment, the cypriotturkish and cypriotgreek ethnic-nationalists competed to write the city via ethno-religious affiliations, exclusivity and homogenisation, which generated the dominant and official narratives shaped by a wide selection of renowned works. Such pioneering works include Costas Montis’s Closed Doors, which constructs the city of Λευκωσία through an ancient Greek spirit that maps a Greece-Cyprus, whilst Ozker Yasin’s poetic legacy builds the city of Lefkoşa via the Ottoman martyrs’ blood that poured into the city like a torrent during the conquest, so as to map a Turkey-Cyprus. In the postcolonial moment, after independence in 1963, literary works like Ivi Meleagrou’s Eastern Mediterranean capture the failures when ethno-religious conflict reigned. Since partition, the city has maintained its significance in Cypriot narratives, where Niki Marangou’s poetry – Nicossieness and Selections from the Divan, for example – capture the everyday life and death of diverse spirits, where childhood memories and other spirits move through the festivals and necropolis of the city, giving her the rightful title of poetess of Nicosia. This city has also hosted various diasporic groups, including not only renowned Cypriot figures – especially Aydın Mehmet Ali, Alev Adil, Stephanos Stephanides, Nora Nadjarian, Miranda Hoplaros, Andriana Ierodiaconou, to list a few – but also renowned migrants, exiles and diasporic figures like Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, the Syrian Kurdish poet Salim Barakat and the Nigerian novelist Chigozie Obioma, who have led the way to capture the city with and through its division, diversity and difference.

This anthology writes back, with and through the aforementioned literatures of Cyprus and the city so as to be the first collection to capture fully this diversity in an all-inclusive and worldy way. It is made up of a wide selection of literary forms, which demonstrate the ways that writing Nicosia results in writing beyond barriers of literary conventions. Here the reader will encounter poetry, prose, prose-poetry, photo-poem, short-stories and plays that are fictional and non-fictional, which gives way to an intersection of genres – a hybrid intergeneric traffic.

Readers will encounter a polyphony of voices, which include the women of Literary Agency Cyprus (LAC) who organised the writing-walking workshops which began this collection’s story, and/or various other literary and arts events organised by LAC. This anthology also negotiates with multiple voices from both or all sides of the Cyprus divide, which includes binaries such as the cypriotgreek and cypriotturk, the north and the south, the left and the right, the city and the country, the dominant and the marginalised. It also moves beyond Cyprus’s binaries, capturing the marginalised position of people, poets and writers in various different contexts. This includes the position of the cypriotarmenian people, as in Aydın Mehmet Ali’s ‘My Accordion Teacher’. It includes poets from different territories such as Africa or India, who share a colonial and postcolonial history with Cyprus, as in Laila Sumpton’s ‘Nursery Tales’. This also includes the position of refugees, as seen in Melissa Hekkers’s ‘Island in the Sun’, displaced university students, as in Tinashe Mushakavanhu’s ‘Nicosia’s African Diaspora’, exiled Arabs who experienced the Nakba and Israeli invasion who speak in my ‘Spatial Tripling-Triad’, and LGBTQ narratives, as captured in Stavros Stavrou Karayanni’s ‘Gardening Desire’. Nicosia is also written from various professional perspectives and disciplines, such as the architect in Adrian Wool-rich-Burt’s ‘Flaş’, the painter in Angus Reid’s ‘In The Company of Birds’, the anthropologist via Yiannis Papadakis’s ‘Story/Language of the Dead Zone’, the musician and rapper in Haji Mike’s ‘The Photo – The Guard Post’, and numerous other perspectives, such as the post-colonialist, ethnographer and rhythmanalyst to list but a few.

These writers also imagine and live the city from the vantage points of those who roam Nicosia’s streets. These include a tour guide, pilgrim, stalker, a feminised flaneur, a radical on a protest march, a vagrant caught in the rain, a ghost hunter and the hunted. Thus, these walkers – Andriana Ierodiaconou’s ‘The Heart of Nicosia’, Marianna Foka’s ‘First Call’, Stephanos Stephanides’s ‘Broken Heart’, Dize Kukrer’s ‘The Endless Day’, Dinda Fass’s ‘Calliope’, Maria Kitromilidou’s ‘Beyond Barriers’, Zoe Piponides’s ‘Hot City Dream’ – set off without a map, itinerary, fixed starting point, destination or idea of how long their journey will take them, and only the beating pulse and rhythms of the city marks time passing. Readers will walk through the city without a compass point, with frequent detours that go off the beaten track, moving beyond all signposts that mark the geo-political barriers.

In this book, the heart of Nicosia is captured in Venetian ramparts, British colonial parks, via ancient Greek gods, Byzantine saints, Ottoman baths, on balconies, and in the bookshops of the 1930s; in the taste of Lahmacun/Lahmajoun and souvlaki; in the scent of jacarandas, jasmine and cicada; in the voices coming from mosques and churches; under red flags, blue flags, white flags; and in all the varied daily practices within the streets of the city. Nicosia’s beating pulse is often experienced through the practice of border-crossing and border-stopping at the immigration checkpoints, forbidden zones, or the dead zone between north and south Nicosia. Such border-crossing narratives were triggered by the opening of the borders in 2003 when all Cypriots were able freely to border cross to see places and people they had been prohibited from seeing for thirty years. The year 2003 became a moment where Cypriots partially replaced the 1963–1974 nightmarish stories with more positive 2003 stories of reconciliation. Such stories have not as yet been successfully institutionalised or nationalised, yet the narratives in this book capture fully that moment of possibilities. One pioneering text that captures this moment is Alev Adil’s ‘Fragments from an Architecture of Forgetting’. Other texts straddling this time include: Adrian Woolrich-Burt’s ‘Flaş’, Haji Mike’s ‘The Photo – The Guard Post’, and Maria Petrides’s ‘Coccinella, or Beyond Data’. Some writers have chosen to focus directly on the experience of border-crossing: Rachael Pettus’s ‘Ledra Street Crossing’; Kivanc Houssein’s ‘A Walk Through Ledra,’ Nobert Bugeja’s ‘Ledra’, Shola Balogun’s ‘I Too Shall Anoint the Stones’ and Mary Anne Zammit’s ‘Shades of a City’ come immediately to mind. These writers perform within the thriving-festering spaces of the dead or forbidden zones, buffering before the buffer zone, scratching at the neurotic act of border-crossing and re-crossing from one side of the divide and back again.

This crossing process also engages with time. On 30 October 2016, Turkey and the north of Cyprus opted out of the practice of Daylight-Saving Time, thus dividing the north and south of the island into two time zones. This inspired a new narrative among the people in Cyprus and the world as depicted in Antoine Cassar’s ‘Leaving Nicosia, Part Six (from Time Zones)’, Argyro Nicolaou’s ‘A Waste of Time’, Hakan Djumam’s ‘The Missing Hour’ and Zoe Piponides’s ‘High Five’. The Nicosia experience and the way it has changed over the years depending on the political situation is further explored through pieces of writing that cover a significant lapse of time, such as Elisa Bosio’s ‘Blue Ants, Red Ants’, Münevver Özgür Özersay’s ‘Buzzing Bees in my House’, and Sherry Charlton’s ‘Nicosia Through the Eyes of a Child’. Through different generations, and joining writers at different points in their story, the reader feels what it is to be in Nicosia at different stages in the city’s history.

Nicosia is likened to other former British colonial cities in Zimbabwe/Rhodesia in Caroline Rooney’s ‘Serendipity’, and India and Palestine in Shereen Pandit’s ‘Divided Cities and Black Holes’. Going further afield, Nicosia as an ‘other’ city is given in Christos Tsiailis’s surreal short story ‘Knit’. Here, an alternate reality where giant roots strangle the buildings of the city and bind its inhabitants together in a shared semi-conscious stupor, induces the Nicosian experience. Nicosia is invented, un-invented and re-invented through architecture as in Christodoulos Moisa’s ‘Right-Hand Corner’ and Sevina Floridou’s ‘Small Stories of Long Duration’ and through language and translation, as seen in Stephanos Stephanides’s ‘Rhapsody on the Dragoman’, Jacqueline Jondot’s ‘Why Are Green Lines Called Green?’, and Yiannis Papadakis’s ‘The Language of the Dead Zone’.

Thus, as a collection these works reveal the ways writing can move beyond dominant binary legacies of historical-political deadlock by creating a new literary form, language and geography, so that deeply divided and displaced inhabitants can speak to each other and to us about the important truths of Nicosia. These are truths that accommodate opposing forces, where the inhabitants are the victims and culprits of hostility, violence, pain, as well as advocates and opponents of the hospitality, peace and pleasures that make and break partition. This is a truth where global and local, powerful and powerless, rich and poor, marginalised and dominant actors can meet and speak so as to have a healthy relationship with the environment, which defines and disturbs the divided city and divided world. Thus Nicosia, Λευκωσία, Lefkoşa truths teach us about being citizens with and without the right to the city and the right to the world, where we can all conceive, perceive and live divisions, diversity and difference so to create a city and world without discrimination, where in solidarity we can live in longing for a transnational city and world beyond barriers that maybe one day will exist.

Nicosia Beyond Barriers

PAINTING IN THE WALL

Erato Ioannou

Pssssssst … psssssssssssssssssst! Pssst!

Can you hear me?

Can you see me?

Crack of dawn marks my entrance to this world. Small colourful drops sparkle in the moonlight. Pssssssst … psssssssssssssssssst! A colourful mist of an umbilical cord connects us –

my creator and me – just for a short moment. After, the wall sucks the colour in. And I become.

Smell of paint in my nostrils, oozing from the pores of my skin. Hasty steps leave me at dawn. His backpack, hanging on his shoulder, swings to the rhythm of his walk until his backpack, and his hooded head, and his manly swagger melt in the hazy contours of the city as humidity veils Nicosia in the young hours of the day. His footsteps can be heard in the distance, echoing against the walls, but not for long.

All I know is that I am. I am something. I am a thing inside a wall. Spray painted. A work of art by an artist of questionable merit.

At nights I push. I push real hard, but it’s no use. I push in spite of that. My palms go numb against the sturdy cement surface.

‘Hey, Kid! You on the opposite wall! Yes, you with the giant head and big teary eyes. Can you hear me? Can you see me?’

In the mornings, dogs pee on my feet. The smell of urine masks that of paint, momentarily. At nights, heated bodies press against my flat embrace in the process of clumsy, rushed, upright lovemaking. Other times, hands press my cheek as they lean against me for short moments of dull conversation. And I hear that they too are within a wall. Somehow forced to be there. Somehow, doomed.

‘Psssst! Hey Kid? Here! Here, across from you! Have you ever tried?’

Kid’s giant pupils, with honey-coloured highlights, glide to my direction – painfully slow.

‘Have you ever tried to escape the wall? To walk out of it? Have you? Have you?’

Kid shows me two white teeth between a pair of fleshy lips – the smile of a teething infant. The kind of smile which could be a facial spasm, so beautifully captured underneath the skin, or a mere smirk of contempt.

At nights, I dream of earthquakes cracking the ocean’s floor. Waves tower high into the sky, only to gash down into the bottomless void. Menacing rattle below the surface shutters the foundations. The walls crack. All of us glide through the crevices into the warm night – myself, Kid, Aphrodite and the giant sparrow, the woman with the white shawl. We walk unnoticed into the darkness – bodiless, non-existent. Trickles of paint mark our passage until, they too, vaporise into the paleness of the landscape at dawn.

Even in my sleep I push. The wall mocks me. Its surface turns into an elastic impenetrable membrane. I push. The membrane pushes me flat.

There must be something about walls and this town. Walls encircling her. Walls gashing across her. Walls. Walls are meant to protect. Am I supposed to be safe in mine? Shall I strive for escape never again?

There’s this girl. She giggles and talks too loudly. She takes snapshots of the walls. I am used to this. If I could I’d strike a pose. She presses her back against my bosom and her skin feels so soft. A drop of sweat trickles down her nape and in between her shoulder blades. Life is oozing through her and I want to suck it all in. I would kill her if I could – just for a short walk down the road, just for some giggles and a word or two too loud. If only I could be that girl! With flesh and bones and a heart pumping blood into my veins, free to walk the narrow roads without walls to hold me back.

My face shows next to hers on the rectangular screen of her phone. She smiles a wide smile. I have no mouth. I am gagged. Her skin glitters in the sunlight. My surface is rough and scaly.

At night, I think that maybe there is no use. What is the point. I am flat. Embedded. Bodiless. Gagged.

Pssssssssst. Psssssssssst … pssst.

And the night is long.

Psssssssssssssssst. Psssst … pssst.

Endless

Pssssssssssst. Psssst … pssst.

In the morning there is a new one next to Kid. He looks at me straight in the eye.

‘Psssssssssssssssst. Psssst … pssst! You! Hey, you!’ he hollers. ‘Have you ever tried to escape the wall? To walk out? Have you? Have you?’

NICOSIA – WHISPERS OF THE PAST

Anthie Zachariadou

The cities of Europe are filled with whispers of the past and a trained ear can even detect the rustle of wings and the palpitation of souls and feel the dizziness of centuries of glory and revolutions …

Albert Camus

In September 1955, the couple boarded a Cyprus Airways plane to Nicosia, a 15-hour trip with a stopover in Rome. All arrangements had been carefully made beforehand. Michael had thought that it would be best for them to live in close proximity to a good school and the Government House, in a nice little neighbourhood, which happened to be where his mother used to live.

Michael asked Barbara if she wanted to go and see the house where his mother had grown up. He was surprised to find that it had been recently vacated and was available to rent, and that is how, at the age of twenty-two, Barbara found her home. A semi-derelict semi-detached stone-build with a tiled roof, a world away from Cambridge. Located in a street fewer than three metres wide, if she stood in the middle with her hands stretched out she could almost touch the buildings on either side. It was both secluded and claustrophobic. Inside, a wooden door opened up to a yard of cobblestones and withered plants. Barbara smiled when she saw what seemed to be a toilet at the yard end corner. To her left was a closed door made from walnut wood. Barbara lost herself in ideas of what she could do with this place. She held Michael’s hand as they walked around the neighbourhood, all simple, stone blocks stuck together; all so pretty, so obviously loved and cared for.

Grasping the hand of her ever-so English-looking husband, they walked on and found themselves gazing at a pretty church, similar to the chapels in Cambridge, but of a different rhythm – the Greek orthodox style. Michael explained that the church was dedicated to the patron saints of the neighbourhood, Ayii Omoloyitae. The saints’ names were Gourias, Samonas and Avivos, and Barbara smiled at the sound of those names, remembering snippets from her childhood of her dad’s Greek heroes whose stories she had not paid attention to. They walked on, passed through a few more tightly knit houses, and out into another opening. It was the smallest of squares framed only by a couple of coffee shops where old people sat doing nothing. What on earth were they thinking? In the middle, a huge sycamore tree stood, majestic and strong. She moved beneath its canopy to get some protection from the blazing sun. Carefully, she studied its strong dark trunk branches abundant with heavy leaves and she had a sudden yearning to paint it. She felt Michael smiling down at her, as he whispered, ‘You will have ample time to paint it, my darling. Platanos has been here for centuries, it’s not going anywhere’.

That is how Barbara started her life and built her home in Nicosia. She did actually renovate it herself. She discovered old wood workshops and carried planks, found out who sold varnishes and brushes, painted walls, had a new kitchen installed, scrubbed, brushed, sawed even, enjoying every minute of it. She uprooted the green remnants in the yard and planted Michael’s favourites: sunflowers and geraniums, dandelions and lilies. She found that it wasn’t difficult to move around the area, it was such a compact place. She bought a bicycle, taking what she needed with her.

The days passed peacefully. Michael was content teaching and Barbara, when she had finished restoring the house, took up painting again. She discovered a little art shop not far away where she could get most things, and her mother sent over parcels containing anything that she couldn’t find. She turned the room with the walnut door into an art studio, and she also enjoyed painting outdoors. By Christmas she had completed portraits of the old lady living next-door to them and of the man around the corner, Mr. Costas, a shoe repairer, who could always be found sitting on his doorstep with his awls and scissors and someone else’s shoe. The pretty chapel with the sculpted bell-tower and the school of Ayii Omoloyitae were her favourite places to paint. She had a folding chair and her easel and canvas and brushes were easy to take out, under the lovely blue Cyprus sun, in the comfort of a light breeze. She loved that she could walk around without worrying about catching a cold, how she would greet everyone who passed by and they would smile and look approvingly at what she was doing. Platanos was an ongoing project, she needed to make it perfect, so she took her time.

It took several months for Barbara to understand that she was not, in fact, in paradise. She had heard a few shots over the course of several days and caught worrisome words on the radio, but Michael always reassured her, talking of practice military runs, or some drabble between the Greek and the Turkish Cypriots. But as happens in all marriages, she got to know him. She noticed his eyes grow a touch sadder, heard anxiety not tiredness in his sighs. The excitement of teaching maths to eager students began to fade, and then she knew enough about him to understand that routine was not to blame, but something else. She did not want to ask her neighbours. They had bonded and she had painted their children and animals and gardens but she was still a foreigner to them and she did not want to hear the answers she did not want: not from them, not yet. She decided that she would pay more attention to the news and read the papers.

One day in 1956 she heard on the radio that an English student, Michalis Karaolis, had been hung for treason. Her heart stopped for a while. What could a twenty-two-year-old have done to deserve hanging? And then it wasn’t hard to put together all the pieces she had chosen to ignore, to mature, to read in the look on her husband’s face as he opened the door to their home that night that they were British people living on an island governed by British people, and that the Cypriots did not want them there.

She would never, she promised herself, never bother Michael with this. She would not spoil for him the dream that she was perfectly happy painting away, chatting with neighbours, cycling in the town, cooking, gardening, carefree, clueless. She felt that the only way she would help him was providing this distraction for him, the serene wife. She knew the dynamics of their marriage and she would play it right. She would be the little girl who could cheer the old man up. And Michael did seem to grow older by the day. With every explosion they heard, every time he returned from a ‘late evening class’ when she knew he had been summoned to meetings at the military headquarters, with every slight noise, every start of every news story on the radio, Michael’s eyes appeared more wrinkled, lines forming underneath them, creases around his mouth. But her duty was to stay young for him. So she did.

She asked him nothing, and pretended that everything was fine, even after they attended dinners with British officers and their wives, who were all making plans to return to the UK. But she did her own research, and she learned by chatting casually with the locals – from the girl who she bought pastries from at the Mondial sweet shop to the priest she ran into in the street whilst out walking. Pater Vasilis took her to see the old catacomb underneath the bell-tower, and there he explained, calmly, what was going on. The Greek Cypriots wanted to be real Greeks. They wanted enosis. She wished she could call her father and ask him what that word meant, but now it was too late. He would worry and command her to come home. In every letter she sent to her parents she reassured them all was fine. How could she tell of Grivas and his fixation, the guerrilla fights or that some of Michaels’s students had been involved in the escalating attacks against the British? By 1957, a Briton was attacked or killed every few weeks. Barbara concentrated on shaking off all uneasiness and upped her efforts to mingle with the Cypriot people. She needed to see if they all viewed her as an ‘enemy’ or if this was just a bunch of extremists, ‘trouble-makers’ as the governor had told her. Did they only hate the fact that they were under British rule or was there something else: a desperate need to be real Greeks, not Greek Cypriots, not Cypriots who spoke Greek?