Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

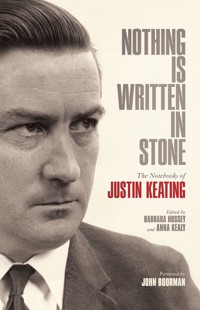

Justin Keating, son of the artist Sean Keating, attended UCD and TCD. He was a Labour Party politician (Minister for Industry 1973-77), academic, journalist, veterinary surgeon, television pioneer (as Head of Agricultural Broadcasting at RTE) and award-winning documentary filmmaker. In later life he served as Member of the European Parliament and became president of the Humanist Association. President Michael D. Higgins called him 'a man who saw socialism as both essential and adaptable to change'. Keating introduced the first substantial legislation for the development of Ireland's oil and gas, set up the National Film Studios of Ireland at Ardmore and gave impetus to Kilkenny Design. He wrote extensively – and with opinions well ahead of his time – on the natural world, including women's health, animal welfare, sustainable energy and ecology. 'A well made, fit thoroughbred really striding out seems to me one of the most beautiful things on earth, on a par with an orchid or porpoise.' Edited posthumously by his wife, Barbara Hussey, Justin Keating's notebooks offer an in-depth, often-impassioned account of the interests, musings and opinions of one of Ireland's most wide-ranging intellectuals. His dealings with J.D Bernal, Noël Browne, Sean McBride, Charles Haughey, Gerry Fitt and Conor Cruise-O'Brien, form part of this absorbing chronicle, aside from myriad friendships with writers and artists. Nothing Is Written in Stone is a brilliant selfportrait of this multi-dimensional man, who did so much to shape twenty-first century Ireland.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 544

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

Contents

Foreword

Preface

Editorial Preface

Acknowledgments

Chronology

Introduction

1. Acorns to Oaks

On Education

2. The Godless Institution

On Marxism

3. Snakes and Ladders

On Women, Religion and Sexuality

4. Genesis v. Gaia

On The Care of the Earth

5. Entering Irish Politics

On Ireland’s Future

6. Northern Ireland and Other Politics

On the Perils of Nationalism

7. Doubt is the Mother of Wisdom

On Zionism

8. Globalization and Democracy

On the Future of the Left

9. Loves, Loss and Leavetaking

Epilogue

Appendix A

The Greening of Humanism: On the need for a greater ecological awareness

Appendix B

Oil and Gas Licensing Terms

Appendix C

Barron is Right about 1974 Bombs

Appendix D

The Zionist State Has No Right to Exist: Justin Keating on Israel

Bibliography

Illustrations

Copyright

Foreword

It was 1973 and there were problems. I was preparing to shoot Zardoz at Ardmore Film Studios. We were building sets. Seán Connery and Charlotte Rampling were on their way.

The carpenters demanded equal pay with the prop men. The prop men insisted on maintaining their differential with the carpenters. It was intractable. We ground to a halt. I needed a lot of rifles for the picture. For a film you hire weapons from Bapty’s in London, but there was a war raging in the North and there was a strict prohibition on importing weapons, even ones that couldn’t fire bullets. One of the offending carpenters whispered in my ear that the lads from the North could get me all the guns I needed.

Justin Keating was the newly appointed Minister for Industry and Commerce. I sought an audience and listed my woes. He looked stern. At the mention of the IRA offer he bristled with fury. He made notes. I found him intimidating. Oh, by the way, I said, the studio is going broke and threatening to close us down. Would the government consider taking it over? His severe visage broke into a crooked smile. He said, Is there anything else I can do for you?

He acted decisively. We got our weapons. The carpenters and the propmen were shamed at stopping the movie. They kissed and made up. Justin bought the studio.

He became a friend. And on many an occasion, with the help of a couple of jars, I began to realize what an extraordinary man he was. He wanted to root out corruption and cronyism from politics; he was a lapsed Communist but wanted Ireland to become a socialist republic. He believed that the Catholic Church was an oppressive colonial power that had kept the country weak. He planned its demise. Despite (or because of) having a Jewish wife, he was passionately and publically anti-Zionist. He was cultured and well read. He had a grasp of history. He knew all about agriculture and how to feed the world, and about our obligation to nurture the earth. He was so far removed from the tribalism and village pump politics of Ireland of the day that one wondered how on earth he had got into government.

A couple of years later I was shooting at the Warner Brothers Studios in LA. Justin called me to say he was coming over to drum up business. I told the studio how important he was. He came on to the set, where a huge floral tribute awaited him in the colours of the Irish flag. The crew and cast applauded. He was not in the least embarrassed.

What a delightful surprise that Justin speaks to us from beyond the grave, as it were, with all the old brio and wit and wisdom. We owe a debt to those who rescued these notebooks so long after his death.

At his humanist funeral where no priest dared show his face, his son David spoke eloquently of his father’s multifaceted life, and as he was lowered into the grave in his cardboard coffin I joined his comrades from the Labour Party in singing ‘The Internationale’. Michael D. Higgins was in particularly good voice, I recall.

John Boorman, Wicklow

Preface

After I retired from legal practice, Justin and I were able to spend time in a family house in the Languedoc in France, and most days while we were there he would devote time to writing in his notebook, a simple copybook bought in the local shop. I can see him now, settling down at the table. Once he began to write, the words seemed to flow for him. He left eight notebooks. The earliest is dated July 2006, the final one October 2009, and for one or two there is no date.1

He wrote down what he could recall from memory and expected to have time to check details later; he didn’t get that time. So I have done that to the best of my ability, but lacking notes to work from, I may have overlooked items he would have checked. For instance, some poetry extracts are educated guesses, with only the poet’s name for guidance.

Justin lived his life as though he had forever – a wonderful way to live, considering the dire warning he had been given upon his diagnosis with Paget’s disease in the late 1970s. However, on the last day of 2009, with snow on the ground, he went to bed for a rest and never woke up. He was just seven days short of his eightieth birthday.

As he would have said, why am I telling you this? Well, the notebooks were there, of course, uncorrected and unfinished. For a time they remained in a filing cabinet – I found it very painful to open them because his voice comes through so strongly in the writing. Slowly, I started to read them and realized he could make me laugh still, and his ideas were interesting. Using speech dictation software, I read his words aloud and found I had the beginnings of this manuscript. I emailed the first part to my stepchildren, Carla [King], Eilis [Quinlan] and David. They were intrigued and wanted more. I moved house twice in the meantime, but eventually all eight notebooks were transcribed. It seemed to us that much of what he had to say was relevant to today’s world.

Things he didn’t write about

Justin loved his three children deeply, as well as his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Yet in his notebooks he had not got much beyond the description of their births and the delight he experienced with Laura then. He did not plan to die before finishing his book. He would have regretted not getting the time to write more. But there is also very little about his father Seán, and again, I think he intended to come back to that – a recurring phrase in the notebooks. However, there is a passage in which Justin describes his father as the most honest man he ever met. I suggest that the theme of reworking his paradigm, which lies at the heart of the book, is an attempt by Justin to re-examine and not only correct, but also acknowledge, his mistaken attitudes/stances and actions and take responsibility for them. A phrase he liked was ‘If you show me better, then I must change.’

Another surprising omission is that of humanism. He devoted a lot of time and energy to the movement, and yet there is barely a mention of it or the important role he played in attracting people to learn about it. While he wrote with conviction about the teaching of religion and the damage he believed it has caused, it is unfortunate that he didn’t get the opportunity to write about the positivity of the humanist ethic for its followers. One of his articles, ‘The Greening of Humanism’, is included in the book.

He was a gregarious man with a wide circle of friends, and a good storyteller. However, in the last four or five years of his life Justin became less mobile as the Paget’s disease took hold, and he endured a lot of pain.2 One of the crueller twists of fate was that his hearing went; in restaurants or crowded places he struggled to hear the conversation. By happenstance the pitch of my voice is such that he could usually hear me, so at times I took on the role of intermediary.

Justin was widely acknowledged as a brilliant communicator. In tribute, Brendan Halligan wrote: ‘Cool, rational and patient in debate, his forensic skills in assembling and deconstructing a debate were legendary.’ He believed that communication was a skill, and it was one he worked at and honed for each lecture and speech until he was satisfied. On television, he had a way of leaning into the camera to better convey his point. He often criticized those who delivered their message ‘from above’ with this quotation from Oliver Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village:

And still they gazed, and still the wonder grew

That one small head could carry all he knew.

Those expecting an academic’s tone might be surprised by his conversational style. My sense is that this was intentional, because Justin wanted to examine complex ideas without distancing any part of an audience.

Along the way I have wavered about publishing the book, but was spurred on by the encouragement I got from David, Eilis and particularly Carla, who has been hugely helpful and endlessly patient. I am pleased that Lilliput Press is publishing the book and I look forward to its launch and its reception. My greatest regret is that Justin is not here to debate the issues with readers.

Finally, I want to thank Anna Kealy, who has done a huge amount of work editing the book with me. It was not an easy task. The family and I wanted to make sure Justin’s voice came through in the book and she was most meticulous about this; even when her judgement might have urged her to tweak a bit here and there, she stuck to her brief. Her contribution was enormous and I could not have got the book to publication without her help. It was a pleasure to work with her on the project, particularly when there was time for coffee, chat and the odd piece of chocolate cake.

Barbara Hussey

1. The original notebooks will reside with the Justin Keating papers in the University College Dublin Archive and will be available once the papers have been catalogued.

2. Paget’s disease of bone accelerates the generation of new bone tissue. Affected bones can become soft and fragile over time, leading to bone pain and deformity.

All eight handwritten notebooks.Courtesy of Anna Kealy.

Editorial Preface

When Barbara approached me for help in editing Justin’s notebooks, I was intrigued. It has turned out to be a uniquely fascinating project, not only in its wide-ranging, forthright content but also in its complexity as an editorial brief.

In their raw form, the notebooks were a work obviously interrupted. Life episodes, vivid anecdotes and impassioned arguments unfurled in no sequence beyond that in which they had come to Justin with pen in hand. He had composed multiple drafts of many episodes – consistent in fact, but varying in context or intricacy – and these had to be streamlined or merged as seamlessly as possible. The scope of his subject matter was immense, and he had left gaps in the text or notes to himself where he had intended to confirm details, to later expand upon a topic, or to connect it to another theme. Barbara invested long hours of research and consulted individuals to resolve lingering queries. Here and there a word in Justin’s script was illegible, and amateur handwriting analysis came into play. Where a glancing reference was made or where additional information would be necessary or illuminating, footnotes were composed. Justin had envisioned a bibliography; this too was compiled and included.

Justin had also jotted down a few notes on his own intentions for the completed manuscript: major themes, a skeleton structure – and some keywords that now tantalize. We can’t know what else he might have added (or indeed altered, come revision time). The text in our hands called for a bespoke structure, however. Of several alternatives, we settled on a structure of nine chapters progressing chronologically, each containing a section of personal narrative and a corresponding thematic segment. In this, the idea was to strike a balance between providing accessibility for readers and honouring Justin’s firm belief that his own story was of less consequence than his conclusions – but that the path between the two was paramount.

On a personal note: rarely does an editorial project combine all the satisfaction of an intricate puzzle with such a riveting array of topics. In the many months’ journey to publication, not a week went by without some national or international event relevant to the notebooks’ contents. A great many project meetings began with an overview of these and some musings as to what Justin’s thoughts might have been. I have come to admire his intellectual honour and curiosity; it feels strange to bid farewell to a voice I never heard in life, but which now seems very familiar. I hope that those who knew him best and those encountering his thinking for the first time in these pages will be equally absorbed.

Anna Kealy

Acknowledgments

A large number of people have helped us along this journey from the handwritten notebooks Justin left to the finished book, whether with advice, information, permissions, encouragement or some combination of these: our heartfelt thanks go to all, including and beyond those named below.

The National University of Ireland has very generously awarded a grant in respect of the publication of Nothing Written in Stone: The Notebooks of Justin Keating, for which we are extremely grateful.

Especial thanks to David Keating, Carla King, Eilis Quinlan and Laura Kleanthous for permission to publish some of their personal photographs in the book, as well as their generosity in answering queries we raised and clarifying matters when the need arose. Thanks too to photographer Stan Shields of Galway, Asta Helleris, Paul Helleris, Helena Mulkerns and Lelia Doolan.

David McConnell, Honorary President of the Humanist Association of Ireland, kindly granted us permission to reproduce the article ‘The Greening of Humanism’; thanks also to Billy Hutchinson, Nicolas Johnson, Catherine O’Brien and Brian Whiteside. Brian McClinton, then editor of Humanism Ireland, was extremely receptive and helpful.

Our thanks to Trevor White, former editor of The Dubliner magazine, who granted permission for the reproduction of the article in Appendix D, and to Rabbi David Goldberg, for permission to cite from his response.

Others whose assistance was much appreciated: Dominic Martella, UCD Faculty of Veterinary Medicine; Kate Manning, UCD Archives; Dr Attracta Halpin; solicitors Linda Scales and Andrea Martin; Caroline Hussey; David Waddell; members of the Labour Party, including Senator Ivana Bacik, Tony Brown, Barry Desmond, Brendan Halligan, Ruairí Quinn, Denise Rogers, Willie Scally and Alex White.

A great deal of research went into identifying and confirming details from the original notebook text, and we received invaluable help in this from many and varied quarters.

Our thanks to those who helped on the topics of farming and television, particularly James Conway and Conal C. Shovlin, who responded to an appeal on the RTÉ radio programme ‘Countrywide’ by forwarding copies of their Telefís Feirme Certificates of Proficiency signed by Justin. Damien O’Reilly, Ian Wilson, Tom Llewelyn, John Holland, Larry Sheedy and Mary O’Hehir also helped us on that quest.

In addition, we are grateful to: Louis Keating and Eimear O’Connor, for their help on Seán Keating; Michael Viney, who was able to identify the ‘dally dooker’; Biddy White Lennon, Guild of Foodwriters, Florence Campbell and Nigel Slater for their help with the date of the Observer amateur chef competition in which Justin was a finalist; James Harte at the National Library of Ireland; Lizzie MacGregor of the Scottish Poetry Library, who quickly identified Ronald Campbell MacFie’s work from the few lines we had; Neil Ward, for his help on figures for spending on education; Ann Butler, who provided information about the works of Úna Troy (Elizabeth Connor); Margaret Quinlan and Owen Lewis for deciphering an illegible energy-related term; Una Keating, for her information on the trial of Charles Kerins; Michael Gorman, for lending us the book Fallen Order: A History.

Warm thanks to Maire Bates, Lorna Siggins, Joan Fitzpatrick, Don Buckley, Brid Fanning and Gerard Fanning, Marianne Gorman, Kaye Fanning and John Fanning, Katrina Goldstone, Gemma Hussey and Brian Hussey for their help and support throughout.

Many thanks to David Dickson, Professor of Modern History, Trinity College Dublin for his invaluable advice and guidance on the manuscript, and to pre-readers David Keating, Loughlin Kealy and Tom Hoban.

Lastly, we are most grateful to Antony Farrell and the Lilliput Press team, including Djinn von Noorden and Suzy Freeman; Niall McCormack, who designed the cover; John Boorman, for penning the Foreword; and Bill McCormack, for his voluntary contribution on the index.

Chronology

1930 | Born in Dublin to May and Seán Keating (7 January)

1935–38 | Primary school at Loreto Rathfarnham

1938–45 | Secondary school at Sandford Park School, Ranelagh

1942 | Witnessed murder of Det. Sergeant Denis O’Brien (9 September)

1944 | Witness at Special Criminal Court trial of Charles Kerins for Denis O’Brien’s murder

1945 | Passed Intermediate Certificate

1945–46 | Dalton Tutorial School, Rathmines

1946 | Matriculated and began pre-med at UCD

1946 | Joined the Labour Party, founded Rathfarnham branch

1951 | Graduated from UCD with MVB;3 enrolled at University College London

1953 | Married Loretta Wine at Caxton Hall, London (9 May)

1955 | Returned to Dublin and lived in a flat in Kenilworth Square

1955–60 | Worked at UCD Veterinary College, Dublin

1956 | Carla born (9 April)

1958 | Built house in Bolbrook, Tallaght

1958 | Eilis born (18 January)

1959 | Research in Sweden, France and Denmark; chose TCD over UCD

1960 | Joined TCD as a lecturer in veterinary anatomy

1960 | David born (30 May)

Early 1960s | Joined the Grassland Association; became veterinary correspondent of The Irish Farmers Journal

1965 | Took two-year leave of absence from TCD; became Head of Agricultural Broadcasting in RTÉ; left Labour Party

1965–67 | Made Telefís Feirme and On the Land

1967 | Made television documentary Surrounded by Water

1967–68 | Rejoined Labour Party

1968 | Made Into Europe?, contributed to Work, both documentaries

1969 | Elected as Labour Party TD in North County Dublin

1969 | Sold Bolbrook and bought Bishopland Farm

1973 | Among Ireland’s first participants in European parliament: Jan–Feb 1973

1973–77 | In government (coalition with Fine Gael): Minister for Industry and Commerce

1975 | Set up National Film Studios of Ireland

June 1977 | Lost seat as TD – constituency had been reduced by one seat

1977–81 | Elected to the Senate from the Agricultural Panel

1977 | Elected Dean of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (UCD)

1977 | Received diagnosis of Paget’s disease

1978 | Resigned as Dean, and as Associate Professor in Department of Veterinary Anatomy in UCD

1979 | Made A Sense of Excellence – four programmes on Ireland’s manmade cultural heritage

1983 | Became Chairman of The Crafts Council of Ireland

1983 | Made six-part television programme Love’s Island, on Cyprus

Sept 1983 | Politics programme on RTÉ: Keating on Sunday

1984 | Member of the European Parliament (February–June)

1984 | Appointed Chairman of the National Council for Educational Awards

1987 | Finalist in UK Amateur Chef Competition

1992–97 | Adjunct Professor of Equine Science at the University of Limerick

1995 | Appeared in Where Do I Begin, a documentary on Seán Keating directed by David Keating (broadcast in 1996)

1998 | Elected President of the Humanist Association of Ireland

July 2004 | Finalization of divorce from first wife, Loretta

2005 | Married Barbara Hussey (3 February)

2008 | Interviewed by Rístéard O’Domhnaill for award-winning documentary The Pipe (2010)

2009 | Died aged seventy-nine, at Ballymore Eustace (31 December)

3. Medicinae Veterinariae Baccalaureus, or Bachelor’s degree in Veterinary Medicine.

Introduction

I have been described as an ‘opinionated little git’, and I think that is fair. I have opinions on almost everything. Perhaps foolishly, I have done many different things in my life, and have therefore inevitably had a complex set of experiences. I don’t think the recital of the detail of my life is of much interest, even to me. I have retained poor documentation and have no new revelations. I am not going to reveal or discuss the details of my private life, except in the broadest and most anonymous terms; it is not important (except to myself and those who love me).

Those who want scandal or the making public of things hitherto secret must look somewhere else. There is plenty of politics in it – but for the details, chapter and verse, of what went on during my time in government, a splendid account has been given by my friend Garret FitzGerald. The documentation is enormous. It will all ultimately come into the public domain. And during the last quarter-century I have lost interest in party politics (it is not where the real action is), just as I have in the TV and film industries, in which I used to have a deep interest. I can see no reason to think that my life has been so unique and extraordinary as to merit an autobiography, except that … something of the politician remains. (There is always an escape clause.)

Since the early 1980s I have been progressively incapacitated, although I was able to do a few useful things of which I am proud, such as chairing the National Council for Educational Awards and, best of all, the establishment of the Faculty of Equine Studies at the University of Limerick. But I was not in continuous employment, and for much of the time I was not in an intense personal relationship. There’s a famous question from a questionnaire by the late unloved Senator Joe McCarthy, which asked in its zeal to sniff out subversives: ‘Do you read books?’ And that was my salvation in the 1980s and later: I read books.

I realized that I had inherited a whole ideas system just by being born in the time and at the place where my consciousness formed. I did not choose it. Part of what I got, I feel lucky about and have retained, but much I have discarded. One might say that since retirement I have been reworking my paradigm. In that reworking I have reached conclusions, but as a humanist with a scientific training, I hold those conclusions lightly. It is a point of honour not to remain ‘true to my beliefs’. On the contrary: the honour lies – if you show me better – in changing. And I hold these beliefs with various degrees of firmness and subject to continuous revision, so that they almost certainly contain inconsistencies. I have been modifying the software of my brain for all of my conscious life. I hope to be doing so until the day I die.

When I was in my teens I had many passionately held beliefs about almost everything, but they were diffuse, scattered, unconnected. The core of the paradigm was the great narrative of Communism. I also had strong opinions about food, mostly derived from those of my beloved aunt Mary Frances. I was very involved with gardening (here the influence was my mother) and with the countryside in general. I turned away from the city, though it was on my doorstep, to become a vet and a farmer. But the various beliefs, about God or sex or class relationships or food or global arrangements, were separate, not much worked out (though I didn’t think this at the time) and held in what across the decades I can only call a ‘Catholic way’, by which I mean ‘certainty received via authority’. The content of my paradigm was quite different, but my method of thinking was much the same as if I had been a Jew or a Muslim or Christian. I had never heard of Cromwell’s explosion of exasperation: ‘I beseech you in the bowels of Christ, conceive it possible that you may be mistaken!’ I did not know enough to realize that I didn’t know everything.

But six decades later my beliefs, though all lightly held, are growing together. The particular individual, accidental influences that build our youthful paradigm are mostly worked through, many of them rejected. But what surprises me a little, and gives me pleasure, is that the different bits are becoming reconciled and working their way into a single system. The way that I want to cook and eat and dress are all of a piece with my ideas about global warming, the defence of the ecosphere, Gaia4 and the threat of nuclear extinction.

What I think is important, not just for me but for all of us, is the understanding that the paradigm received in childhood is a matter of accident: of where it was in the world that one’s consciousness came into being. That has no more value as a life guide than any other life guide. Who can claim that the beliefs they inherited – some of which were forced upon them aged five or six or seven – were the best to be had, and that clinging to them through thick and thin is somehow a virtue? To me, the opposite is true. Show me better and I must change.

The faith-based affirmation ‘I am right because my God told me’ is the road to the destruction of humankind and the rest of our present natural world. I very strongly think that by holding beliefs by ‘faith’ or ‘revelation’ or the contents of some old book written in a different age, one does something very wicked which in our current world threatens the survival of our species in a way that it did not prior to the technological advances of the twentieth century. Since the dramatic expansions of chemistry (especially organic) and metallurgy – and subsequently of material science, atomic physics, world population, the science of arms and the rate at which we consume the earth’s resources – we have a killing power completely new to human experience, making it more rather than less likely that we will destroy ourselves. If we continue to try to run the world using mainly a Judeo–Christian–Islamic paradigm, our species will become extinct quite quickly. Mayr (a very profound biologist) has estimated that most species last about 100,000 years, and our time is up.5 Furthermore, I think that those who offer religious certainties to small children when they are at the height of the process of socialization are abusing those children and stealing their autonomy.

But nothing is set in stone; we can survive. Just not with a paradigm based on ignorant and superstitious belief that has its roots almost 3000 years ago. That of most people in most countries is built around a set of religious and nationalist and ‘racist’ myths (the inverted commas are because, in my view, there is no such thing as a race). This baggage is set fair to kill us. My deep conviction is that if many (if not all) of us do not change our inherited paradigm, then we will not survive the next century. This is our most pressing need.

I see very little point in describing a series of experiences I particularly recall. But without listing the big themes that have taken over my mind, without indicating the evolution of my thought, without offering my conclusions after eight busy decades, a mere description would be worth neither writing nor reading. Some readers may want only the narrative. Some may want only the conclusions. But those who read both will find the connection. They will see where the conclusions are coming from. And that they may find interesting.

My justification for writing is this: I wish to record the evolution of my beliefs and then to set out my current conclusions. While I am satisfied that these treat of important questions, they may well be nonsense. So, this book contains a record of the events in my life that caused me to doubt, re-examine and very often change the set of ideas and ideals I grew up with. If it appears self-centred, it is because I have deliberately omitted a great deal: my friendships; the nuanced situations in which I found myself; much about my personal relationships with women; and my dealing with the issue, central to every life, of how we deal with our sexuality. The purpose is to explain the modifications I have made to my paradigm (there is that word again, but I need it) due to my life experiences.

But it is a record of where I am now – as a matter of honour, if you show me better, I must change – and the longer I live, the more I should change. I believe each of us has a duty to rework our paradigm till the day we die.

Justin Keating

4. The Gaia Hypothesis, formulated by chemist James Lovelock and microbiologist Lynn Margulis in the 1970s and introduced in Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (Oxford UP, 1979), proposes that organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings on Earth to form a holistic, self-regulating, complex system that helps to maintain conditions for life on the planet.

5. Ernst Walter Mayr (1904–2005) was one of the twentieth century’s leading evolutionary biologists.

1. Acorns to Oaks

Killakee

The moo-cows were coming up the road; only they weren’t moo-cows, but Mr Doyle’s bullocks. But the age I was, the distinction was lost on me. They were passing our gate and going on to the twenty-five acres of mountaintop above our house that Mr Doyle had rented from my father. Later on, when there was a drought, barrels of water were brought up on a cart and poured into a trough. Out of a desire to help, I added my little bit of piss, which act I was not allowed to forget for years. And the first horse I ever bestrode was Mr Doyle’s carthorse; so flat of back that my short little legs stuck out sideways, so enormous that I was a little bit afraid.

Up the hill at Killakee, at the edge of the Featherbed bog, we lived in the second-last house. The Kellys were at the top, just below what is now the Killakee car park. Our house was a slightly elegant cottage, which was built, I guess, as part of the Massey estate. The ruins of the big house, the ice house which was near our home, the reservoir cottage just at the bend (the reservoir supplied water to the buildings, farm as well as domestic) which constituted the core of the estate; the whole decaying remains of wealthy elegance was part of my childhood playground. And we knew that my father was coming home when we heard the roar of the Harley Davidson as he changed down a gear at the reservoir corner.

Deep snow drifted in front of our house, so deep that it was higher than the front door. My father pulled the frozen door inwards so that there was the vertical face of snow preventing exit. And then a few days later, my father’s brother Joe arrived outside in his car, packed with food to sustain his snowbound brother and his family. I have one other strong memory of my father from that time. He had a beautiful shotgun with a long single barrel; a poacher’s gun, he used to say with a little pride. He was a splendid shot, though he would not kill for pleasure, only for the pot. But what wonders Killakee brought home! Rabbits, of course, and the odd hare. Also, with great pride, the odd snipe. Someone around us was rearing pheasants, and the odd wanderer got snapped up. And best of all, ah, best of all was the grouse. Colonel Guinness, who lived in Tibradden across the valley, used to keep a grouse moor, burning heather and employing beaters for the great days of the shoot. My father’s twenty-five acres shared a boundary with the colonel’s land, and the grouse were poached unmercifully. It wasn’t just for the pot. There was a degree of redistributive class antagonism as well.

Posy Bevins had bright, bright, almost staring wild blue eyes. She helped my mother in the house. With two small children in a cottage with no running water, or flush toilet, or electricity, or gas for heating and cooking, and of course no telephone, it was almost the reverse of what the young are used to now. No grocery delivery on top of the mountain. And then, even housewives without much money could still have servants. Since the range of things that had to be done by hand was so enormous, there was good reason. Now there is every kind of kitchen equipment at the turn of a switch, and a developed delivery and takeaway system for food, but no help. Women are even more overburdened, since men mostly still refuse to take on their share of housework and cooking even when the women go out to work. Blessed are the ways of helpless men. For lots of men, it is a fine art.

Posy had no children of her own at that time, and to some extent that pert little boy (me) enjoyed the role of her surrogate child. ‘Enjoyed’ is the word. She knitted me an outfit in red wool. Trousers, top and a knitted cap. All in red, with a white bobble. We had a bad-tempered Bedlington terrier, wherever it came from. And one day, in a mad mood, she put the whole lot, from trousers to cap, onto our terrier, who enjoyed the game as much as I did. Red trousers on its hind legs, red jacket on its chest and forelegs, red knitted cap with a big bobble precariously on its head. My mother must have been out. I loved my mother, but I loved Posy too – she was so much fun.

At three years of age, or perhaps a little less, the red jumpsuit was important in fixing very early memories. Not as much as the ‘moo-cows’ or Mr Doyle’s house, but after them, the red suit features in my earliest memories. Among the most exciting was wading waist-deep or deeper through crackling autumn leaves on the road at the back of Lord Massey’s house. Those early memories were mostly very happy and nearly always out of doors, even when the weather was very cold. I grew up hardly noticing bad weather.

My older brother Mike was not an important part of my earliest memories. Posy, my mother, and a rather distant father (he always remained so) were the important people. Apart from that, my memories are of the wonderland on the top of Killakee mountain and the paths, trees and streams of the Massey estate.

But there is one darker memory, which influenced my whole life. There was a tiny mountain torrent behind our house. In winter it was full of very cold water, very narrow but surprisingly deep. I was walking across the hillside one day with my mother. She popped across the stream, turned and held her hand out to me. But I, proud of being able to walk across the field by myself (my wife would say I haven’t changed a bit, even though I am crippled by Paget’s disease), spurned the proffered hand and jumped – right into the middle of the stream, which swept me away, submerging me and turning me over. I fetched up what must have been eight or ten feet down at a shallow part, and my mother fished me out. It was not the indignity – I was much too frightened for that – but the terror from total submersion in very cold water, which made me afraid of water ever since. I learned to swim late and with difficulty, and I never learned to relax and trust the water. To this day I fight my liquid surroundings, and the only time I ever swam as I would wish was thirty years later, when I was drunk. Not to be advised.

‘What was it?’ I said to my mother years later. ‘It was dark, I was sitting beside your legs, I was hugging a parcel in a brown paper bag, which was warm and slightly greasy, and we were moving. What was that?’

‘You were hugging your supper,’ she said. ‘We stopped in Rathfarnham at the fish and chip shop in Church Lane. You were in the toe of the sidecar of the Harley Davidson and we were going home, up the mountain to Killakee.’

I didn’t often get to ride in the sidecar, as my father favoured my older brother (there were just the two of us) in the small routine things that old motorcycles required. Mike became an engineer.

I asked my mother (like with the fish and chips) to tell me what I was looking at. If we looked out from across the road we could see Dublin and the bay spread out in front of us. If we moved a bit, we could see the edge of Dun Laoghaire harbour. A bit the other way and we could see over to Howth, Ireland’s Eye and Lambay Island – if the air was clear, up to the mountains of Mourne. That particular day there were a few large ships in the bay, and one of them had a prominent plume of smoke. ‘Why?’ I asked. ‘The Eucharistic Congress,‘ my mother replied, somewhat acidly. The ships had brought Catholics (pilgrims, I suppose you could call them) and then I noticed it was getting up steam to sail away again.

That was our world. Cold, poor, raw land and bog beyond, the ruins of the Massey estate, the Harley Davidson, Dublin spread out in front of us. To the left as we looked down on the city, there was the long reclining shape of Montpelier Hill like a breast, then crowned with the nipple of the Hellfire Club, in ruins, where a century and a half before the bucks of Dublin had caroused. Now the whole skyline is sanitized. Coniferous trees planted all over the top of Montpelier Hill have grown up to obscure the remains of other declamatory buildings, and all is respectable again.

In the 1920s and into my late teens we lived with the occasional disappearance of friends due to tuberculosis. My father had had a fright with TB before I was born. The family feared it. So my mother, the farmer’s daughter from Co. Kildare, kept goats. I never tasted cow’s milk till I was about five years old. And the odd surplus kid goat ended up being eaten also. Ever since, the common meats of intensive farming have seemed pale and flavourless in comparison to the game that formed my first palate, with goat’s milk, and goat’s curd cheese.

There was another strand, later important in my life, which I first became aware of in Killakee. Some IRA men, of whom George Gilmore was the only one I remember well, had built an arms dump towards the bottom of the Massey estate, and I remember the frisson when it was discovered, probably due to a tip-off, and emptied by local guards and detectives. I don’t know when it happened. I didn’t know what it meant, but I have a vague recollection of the phrase ‘arms dump’ and perhaps of the Broy Harriers,6 whoever they were, who found the arms dump. It had been built by IRA men, including our friends the Gilmore brothers. And I remember my parents talking about Jack White, the scion of an eminent British army officer and an officer himself, who had changed sides and trained the Citizen Army. Many years later, in my early teens, I found and devoured a copy of The Communist Manifesto with Jack White’s initials on it.

So there we were, on the top of our mountain. Not many neighbours. Not many other kids to play with. Just my brother, nearly three years older than me, and myself. Aware of wild land and poor farmland, of domestic and wild animals, of the IRA and the Catholic Church, and very much of our parents. My father could do pretty much anything (except cook – perhaps, like a proper man of his day, it wasn’t so much couldn’t as wouldn’t). He made my mother’s gold wedding ring. He was a good carpenter. He made the stained-glass window for the main gable in the house he was just about to build. He was a skilful poacher. He was a brilliant photographer with the new movie cameras. He could take a piece of charcoal and draw a free line at the first try that was unquestionably and unalterably in the right place. About the pictures, at the time I knew and felt nothing.

My mother, I know in retrospect, was a witch. From me, that is high praise. Minding her goats, she could think like a goat. And with fruit and vegetables, it seemed that she could sense what they needed so that they performed with love, evidenced by splendid growth and performance. I have no idea how she knew all these things about the land, the animals and crops. She did not read all that much of instructive texts. But know she did. She was an earth mother. And in a completely non-spiritual way (which she would have mocked), she was in touch with the earth. I hope I learned a little of that from her; at least enough to try.

But the isolated idyll had to end. The land was poor. The house was uncomfortable. My father’s work was in the city and we were far from the primary school that we were to attend.

My father bought a couple of acres of land at Ballyboden, just beyond Rathfarnham village, and designed a house. It was close enough to the nuns’ primary school at Loreto Rathfarnham for Michael and me to walk there. We were about to be domesticated, though ‘civilized’ would be too strong a word. But I have never ceased, to this day, to miss the mountain.

Ballyboden

What surprises me most as I write this, more than seventy years later, was that almost all the main currents of my life were already set before we came down off the mountain, what seems to me in retrospect to have been down from paradise.

The love of nature was already deep in me; of horses, cattle, trees and other plants. I learned then the sense of awe and delight and reverence from contact with nature that has served me all my life, in the way that religion serves many people. I learned that guns, physical force, the carryover from 1916, what I later knew as ‘the national question’, were an important part of life. And I had the first feeling, though very unclearly, that our family was a bit different; that my parents had no great desire to be part of any community, nor had any great respect for the prevailing ideas of our world.

My father was one of the most honest men I have ever met. It was not just that I never knew him to say anything that was not true. But if someone in friendship or admiration said complementary things, which were a bit of an exaggeration, he went back to correct them. Where did it come from, I wonder? Not from his home city of Limerick (‘Mind you, I said nothing’ … ‘Whatever you say, say nothing when you talk about you-know-who’ … ‘Who told you that?’). Maybe from his ‘sceptic’ father. Perhaps in personal rejection of the sloppy mess that was the Limerick of his growing-up. He taught me how to use tools, how to sharpen them, most important of all, to love them. But he was austere and distant.

One of the joys of coming down from the mountain to our new house in Ballyboden was that it offered me new land to explore – much better land than Mr Doyle had rented from my father. There I saw my first warbles (almost totally gone now).7 And there, over the wall from our land, on the edge of a mill stream, was a beautiful oak tree. The cattle loved to shelter under it, and they had mashed the surrounding earth to wonderful fertile mush. Aged about six, I was exploring this. I came on something about the size of the first joint of my thumb. Growing out from one end were two shoots, one going downwards and one up. I had no idea what it was, but I fished it out of the mud, wrapped it in a much-abused handkerchief, and carried it home to my father. What was it? ‘An acorn,’ he said, ‘oak – aik.’ I loved him for word explanations like that. And going down was not a shoot, he said, but the root. Going up: what would be the trunk and branches … of a huge tree. This blew my mind. ‘What should I do?’ I asked. ‘Plant it – maybe it will live.’ I did, and it did. It is three-quarters of a century growing; it is a huge tree now, scattering acorns of its own. And I love oaks more than any other tree, more even than noble beeches and graceful birch, which give us delicious refreshing drinks when the sap is rising. I’ve given mine the odd hug.

We moved pro tem into a nearby gatelodge two houses up from W.B. Yeats’s Riversdale until our house (where my sister-in-law still lives) was finished. I was able, before I was six years old, to go everywhere on the site, and to get the sense of what would be a beautiful house (though not a very practical or comfortable one) in the process of growth. And then the delight of moving in: running water; a flush toilet, rather than the Elsan; a plumbed bath, rather than a tin one on the floor; electricity, with an electric cooker; and, not long after, a telephone.

School

Amid this excitement was the greater one of going to school; a new world for me. The Loreto Convent in Rathfarnham had a co-ed primary school attached to its rather snooty girls’ secondary school. But the boys had to leave before puberty. On the first day Mike hated it and wanted to go home. I loved it, and took to it without a backward glance. I was always walking on his heels and giving him a hard time. Perhaps recognizing that I had grown up with very few friends (and no girls), I plunged into the social whirl of the playground, so wished for after the mountain.

There is a recollection that I am still ashamed of (though not very). The nun in charge organized a competition in a long classroom free of desks and all furniture. The prize was a set of farm animals and farm workers cast in lead, which was placed on a table at the end of the room. Our class was blindfolded and spread out through the room, turned in various directions. Whoever got to the prize first won it. Even before the word ‘Go!’ I worked my eyebrows up and down so vigorously that I could just see out under the blindfold. That’s not the bit I am ashamed of. I had realized that if I made a beeline for the prize I would be spotted, so – seemingly at random, but relentlessly – I fumbled and turned and struck out in all directions (watching if anybody else was getting close) before I very gently and slowly zeroed in on the prize. Nobody noticed my ruse. I was the winner. The propensity to cheat, even at the age of five, worried me. I was somewhat reassured decades later, when I was reading about the behaviour of higher apes, that they did it too.

I don’t know if the precocious development of sexual feelings happens in all children. It certainly happened to me, though it faded again until puberty. Between about three and a half and five I had a brief and very enjoyable period of being sexually aware. I had a sweet and lovely romance with the daughter of the house where my parents rented the gatelodge before our house was finished. We were rumbled by her older brother, who manifested outrage, but I felt no guilt, only warm exciting pleasure. But that was only a tryout for my affair with a nun.

She was a large, strong, cheerful young woman, who did not have the full nun’s costume. She must have been in training; a postulant or something. At break time I used to rush out to the playground, which she supervised. Between us we developed a game that I in my six-year-old head called ‘walk up and turn over’. She would stretch out her arms straight in front of her with her big strong thumbs sticking upwards. I would jump up and grab the two thumbs and walk up her habit, and when I was up as far as I could go I would turn over and land back on the ground facing towards her. And after a while I began to notice things. She seemed to quite enjoy having me walk on her breasts. As the days passed, I ventured further. One day, when I got to the top of her thighs, greatly daring, I put one foot squarely in her crotch and gave her pubis a good rub. She said nothing. She could have ended all this at any moment. But she was there in the playground the next day, thumbs at the ready.

Was this sexual abuse? Was she, aged I suppose nineteen, abusing me, aged five or six? Was I sexually abusing her? I don’t believe there was any abuse involved. I know it was very pleasant. I think she enjoyed it. I had no sense of sin or guilt. I can’t remember how or when it stopped. My sexual feeling, so clear and strong and nice, waned and did not reappear until I was about thirteen. And I don’t remember what became of her. I hope it did not give rise to the terrible guilt feelings, which so plague and destroy so many Catholic lives. If she was ever fully professed, she cannot have found a life of celibacy easy.

Sex was not the only important thing at Loreto. Educationally, I found the work easy and mostly I enjoyed it. A good recollection was of a wonderful German nun, Mother Margaret, who had great hands and taught those who wanted (as I emphatically did) the basics of carpentry in a special woodwork class on a Saturday morning. Marvellous. Michael and I loved it and that buttressed our father’s love of tools and manual skill. I have always had that feeling, which forty years later fuelled my interest in the craft movement. As my father used to say in another context, ‘How can they hate skill?’ I don’t hate it, I love it, and Mother Margaret gave us a start.

The Aran Islands

It is a sunny evening. We are going west down Galway Bay towards Aran on the old Dun Aengus, which served the islands for so many years, and around the boat, in water made golden by the reflected sunshine, porpoises are playing – circling, running ahead of us and generating the extraordinary sense of lightness and fun that sea mammals seem able to do. I don’t remember my mother on the boat. She must have been there somewhere, but the only people that I recall are my father, my brother and Victor Waddington, who was my father’s agent and a family friend. Waddington (we always used his surname) had a Voigtländer reflex camera and took the photograph of us three Keatings. He got off on that occasion at Kilronan on Inis Mór and stayed, I think, at Kilmurvey. The details are hazy now, but nothing can ever erase the sense of beauty and wonder, to the point of awe, that I felt out on the water.

Robert Flaherty had made Man of Aran there years before and became a fast friend of my father’s, as did one of the Aran men in the film, Pat Mullen. He met us on the pier, wearing the traditional Aran clothes. What I remember most about them from that visit was the acrid peat-smoke smell, which I still love and which calls up with great power the islands before the Second World War and the idyllic summers we spent there. I must have picked up enough Irish to play with the local kids on Inis Oírr, as they had no English. The girls had no knickers either and it was there, since I had no sisters, that I discovered the difference between boys and girls. It was a place of innocence then – or at least, if the decay had started I was too young to notice the signals of a dependency culture, or the falseness of the role that romantic myth had given to ‘Celtic’ islanders. My father went to Aran every year, almost always by himself. But we never went after 1939. In the course of the war Seán Moylan, who was a close friend from 1921 and by then a minister in the Fianna Fáil government, asked my father to go to Aran – where he had been an annual visitor for decades, and therefore innocent-seeming – to keep an eye on a German spy. There was not much doubt which side we were neutral on.

I was not back until 1953 and by then, tourism to Aran (aided by the publicity given by the works of Synge and Flaherty, and to a lesser extent, of my father) was becoming more common and the dependency culture had progressed apace. We (my new wife and myself) came thinking we would spend a few nights on Inis Mór, but on the quayside we were approached by a man clad in the now much rarer traditional clothes. He had the great lean rangy physique of fish, cabbage and potatoes and, though he was not young, he had a full set of excellent teeth. His objective was to sell us sweep tickets, and as a judgmental and impetuous young man I suggested that we get back on the boat, still at the quayside, and go back to Galway, which we did. Later on, we had a house in a deeply Gaeltacht part of Connemara, which I will write about later. It was there I began to dislike the local society and its racist Celtic nationalism.

Years later I was on Inis Meáin, the middle Aran Island, with one of the great friends of my life, a Danish actor and theatre director called Hans-Henrik Krause whose great loves were O’Casey, Synge and Bertolt Brecht. We were out on the shore near the pier, where a man was baiting lobster pots with big beautiful pollock, which he had pulled out of the sea in the space of ten minutes. I decided I would show off my cooking skills by building a driftwood fire on the shore and cooking a pollock on the embers. Pollock is a watery bland fish, but the improvised grill dries it out and makes it quite nice. Having said what I intended to do, I walked the hundred yards to the lobster pot man and asked him to sell me a pollock. There were about four on the ground and, friendly, he told me to choose the one I wanted. I did, and said to him, ‘How much?’ He replied with a set of gestures I used to see a lot as a kid. He dropped his chin on his chest, twisted a bit of his forelock around a finger and scraped the ground with his big toe. And after a moment, he said, ‘I’ll leave it to yourself, sir.’ I must have exploded, because Krause said to me as we cooked the pollock, ‘What was that, when you shouted and waved your arms?’ I hadn’t realized that I did, but I hate those gestures of pretended servitude, and I am very pleased to say that the Irish are coming of age and gaining some self-respect. Success is the best cure. The ‘Celtic Tiger’ (I hate that racist term) is healing us.

Detective Sergeant Denis O’Brien

Fit-ups were thriving when I was a kid. Drama, recitations, an unrideable mule, jugglers and – for me, best of all – the trapeze. I believed I could do some of those things too. At home there was a row of beautiful beech trees. The perfect one for my purpose was about twenty yards from the entrance drive to the bungalow that our new neighbour had built. He had two daughters but no son, and I surmise that my pert self was to a tiny degree a surrogate son. He allowed me to walk all over the building site of his new bungalow, and taught me (which I partly felt already from our own house) to love a building site and building skills. He rented our front field, which he cut for hay. He taught me, small as I was, how to sharpen a scythe and cut with it; lots of things. He was a friend. Over a low bough in the beech tree near his drive, I constructed a trapeze. And there I would go every morning and do my set: chin-ups, turnovers, hanging by my ankles; that kind of thing.

One day, which started like any other (it must have been in holiday time because I wasn’t at school), I went out to my trapeze and was just starting up. I heard the engine of his car in front of his house. He drove towards the road. As he passed over a little bridge on the mill stream, I heard what sounded like one or two shots. He jammed his car against the wall, threw open the driver’s door, which he sheltered behind, and with a drawn revolver in his hand faced back towards where the first shot had come from. I was less than twenty yards away and frozen by surprise and fear. And then, across the road towards which he was driving, in the yard of Kyle’s builders, behind his back and in my full sight, a man stood up with what I now know was a sub-machine gun. It hadn’t a belt for the bullets, but a drum. I could see the bullets hitting my friend. I could see him fall, transformed from the lean, hardy, vigorous man he was into a bundle of crumpled rags.

Who was he, my neighbour? Denis O’Brien, Detective Sgt; Dinny, my friend. His killers? The IRA. Apart from those killers, I was the only witness. For some reason I do not understand, and of which I am ashamed, my family was much less supportive towards his widow and daughters than they should have been. Too late, I can only apologize for that sixty years later. Later on I was to go to court, which was trying one of the people involved in the murder, and for me, not personally involved, that was almost as traumatic as witnessing the murder. And again for reasons I do not understand, my parents, usually so perceptive and supportive, paid almost no attention to my trauma. Over the months and years, I internalized it and repressed the memory. I went on with my life. There was plenty beckoning. Only in the last quarter-century have I learnt to let the memory out, and to talk about it.

I have not written these recollections of childhood in sequence. I was blocked. I had clear (and very happy) recollections, but I could not get them onto paper. It was only when I started this part of the narrative, of the murder of my friend, that I got freed up, and the words started to flow. In my early growing-up, the IRA were all around us: the Gilmores and the arms dump; my father’s brother Joe and sister-in-law Mercedes Joyce, who were, I think, still in the IRA prior to World War II; and many others. Ever since, I have hated the IRA and the making of politics with guns and bombs with both passionate and intense anger. Those feelings became important much later in my life.

Later. I am in Collins Barracks, where the Military Court was sitting.8 I was waiting (for what seemed hours and hours) to give evidence. There was a notice on the wall that read There is a place to spit and throw your cigarette ends. I read this over and over, with the emphasis first on ‘is’ and then on ‘place’. And then I was inside, before the soldiers who were the judges, and in the dock was the defendant, on trial for his life: Charles Kerins.9