Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

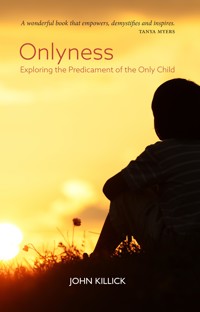

What is the true effect of being an only child? Is it a curse or a blessing, a joy or a challenge? Beginning with a researched account of what makes an only child, from isolation and bullying to self-confidence and resourcefulness, John Killick here traces the development of individuals who at one point in their life, whether temporarily or permanently, have experienced being an only child. Focusing on personal life as well as roles and relationships in the wider world, Killick expresses his own experience of being an Only through narrative as well as memories and dreams. Onlyness is a unique and stimulating exploration of a predicament that faces a growing number of people in the UK, in a time where there are now more one-child families than not.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 114

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JOHN KILLICK was a teacher for 30 years, and has been a writer since his early years. For the past 26 years he has worked on communication with people with dementia, as a research fellow and as a freelance. He has published a number of books on the subject, most recently The Story of Dementia (Luath, 2017), Poetry and Dementia (Jessica Kingsley Publications, 2017) and Dementia Positive (Luath, 2013).

Amongst his general literary works are Writing for Self-Discovery (Element Books and Barnes & Noble Books, 1998) and Writing Your Self (Continuum, 2003) – both co-edited with Myra Schneider. He has also been a small press publisher (Littlewood, 1982–91). His books of poetry include Windhorse (Rockingham, 1996) and Inexplicable Occasions (Fisherrow, 2017).

As an only child himself, he has attempted to come to terms with his situation throughout his life.

First published 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912387-70-0

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by iPrint Global Ltd., Ely

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

The authors’ right to be identified as authors of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Introduction and adaptation © John Killick

Dedicated to the memory of my parents who endured my early struggles

Contents

Introduction

Part One: An Objective View

Part Two: A Personal Story

The Childhood Challenge

Only

One Morning

The Brother

A Grandfather

The Big House

The Wave

The Gate

The Gate (later)

The Scourge of School

Picked On

Three Teachers

Conflict

A Place Apart

Interrogation

Sex and Onlyness

Behind the Net

Aunt Mabel

Smoking with Susie

Dream: Skyscape with Figure

Breakdown

Away Again

Dream: Stop the Carousel!

The Consultation

Night at Llangunllo Halt

Eddies of Nanuto

Teaching Saves

The Pupils

The Girls

Sandra

Jackson’s Due

Supply

Dream: The Face

Service and Sympathy

Being of Service

Seeing the Light

Learning to Love

Music’s Messages

A Musical Conversion

Dream: The Concert

Tallin ’97

Improvisation

Leoš and Me

Musica Callada

The Power of Words

Literature Like Life

Dream: A Visit From George

Don Quixote Drowned

To North

Anglezarke

The Parental Pull

My Late Father

Searching for a Grave

Dream: River

Onlyness and Ageing

A Shared Miracle

A Challenge

Glimpses

A Sufficiency

Ian and Me-ness

Approaching the Mystery

The Barrier

The Point

Dream: Finding My Way

Towards the End

Secret Psyche

A Burial

My Secret Valley

Dream: Last Laugh

Creators and Inheritors

Last Sounds

Dream: Check-Out

Postscript

Introduction

The starting point for this book was reflections on being an only child, and an attempt to trace the development of social awareness and participation whilst retaining one’s essential solitariness. It was never my intention to write an autobiography, but to draw on events from my life to make the struggle come alive. I have read, in any case, too many life stories which mingle the prosaic and the memorable in an unhappy melange. As well as the mundane, I have rigorously excluded references to friends and family amongst the living, preferring to concentrate on the development of roles and relationships in the wider world.

I have from an early age kept journals, and I have raided these for evocations of specific people and events. I have also drawn on a number of my published essays and articles. About a dozen pieces have been specially written to fill gaps in the record.

A further dozen pieces have been written to provide signposts on the journey. They have been composed in a more objective manner, but they reflect my opinions. Most of the pieces vary between narrative and poetic evocation, with a handful in the form of dialogues. I have kept them all short, in the interests of immediacy. A perhaps controversial aspect of the style employed is the predominance of the present tense. This has its drawbacks and I am aware it can cause irritation, but I believe the immediate involvement of the reader is worth the risk.

The book generally follows the chronology of my life, but where a theme is indicated I have not hesitated to break the pattern, believing that a piece can contribute more when grouped with its fellows than strictly adhering to a time-scale.

I have included a number of dreams. In his autobiography, Edwin Muir stressed dreams as a significant part of each individual’s life, and I agree with that judgement. By stressing the link between conscious and unconscious experience I think they can illuminate any attempt to portray the psyche.

All the above refers to Part Two of the book. When I had finished assembling the pieces which constitute the major part of the text, I was very aware of the highly subjective nature of the account, and felt it should be balanced by a short essay prefacing it giving a wider series of views of a subject which has preoccupied writers and researchers over recent decades. This is by no means comprehensive, but offers a guide to some of the main viewpoints to have emerged.

I must acknowledge the following sources for earlier versions of some of these pieces in Part Two:

The London Magazine, Poetry Review, The Reader, The Times Educational Supplement, Writing in Education, The Journal of Dementia Care and the books Dementia Diary (Hawker) and Writing Your Self (Continuum).

PART ONE:

An Objective View

Suppose you woke up one day and couldn’t remember whether you were an only child or not – how, apart from asking others, might you find out? Jill Pitkeathley and David Emerson, in their book Only Child: How to Survive Being One1, suggest placing yourself in a group situation and asking yourself the following questions – who is:

the most responsible person in the group?

the most organised?

the most serious?

the one who is rarely late?

the one who doesn’t like arguments?

the self-possessed one?

The chances are that the one who is all these things will be the only child.

It’s not infallible but it’s pretty reliable as a test.

Of course nobody chooses onlyness; it is a condition which, for good or ill, you are stuck with. And just as those with siblings know nothing different, ‘onlies’ cannot experience what it is like to feel and act as a member of the other family subdivision.

Though that is not strictly true. In considering the nature of onlyness one has to consider that we are not dealing with one concept fits all. As with so many subjects, the simple generalisations keep needing to be unpicked once you get into the details.

Take the definition, for instance. We are not just dealing with the straightforward ‘two parents, one offspring’ set-up. We need to encompass the role of the eldest child before other children come along, the youngest after the others may even have flown the nest, the survivor after siblings have perished; all these can experience periods of onlyness. Then there are those who may be singled out for special treatment by the parents and treated with a degree of onlyness, like the disabled child with abled companions, the gender-favoured child, and the star performer amongst mediocre companions. And in a society where divorce and remarriage are commonplace, there is the adjustment an only may have to make when finding him or herself suddenly with brothers and sisters. Then there is the experience of an only being born into a one-parent family: the dynamic here could be quite different. Any of these occurrences may break the mould, or at the least call for a dramatic adjustment to be made. There is a common observation that if you have spent seven years as an only at any period of your life you count as one.

Nevertheless, there are characteristics of onlyness which can be identified, however much circumstances may later involve their modification. Carl E Pickhardt is a medical doctor who has done a great deal of counselling of families with onlies, and onlies themselves. His book The Future of Your Only Child2 is the fruit of this work. He has provided a stimulating list of what he has identified as the common characteristics of only children, which I will label ‘The Ten C’s’:

Compliant – the tendency to fit in with social norms

Concerned – seeking adult approval for behaviour

Centre – wanting to be the focus of attention

Caution – the reluctance to take risks

Conservative – resistance to change

Commitment – adherence to a set of values

Control – the tendency to manage relationships

Content – being comfortable with solitude

Critical – applying high standards to self and others

Conflict-avoidance – dislike of confrontation

Taken together, these form a useful pattern of an only’s attitude to life.

Pickhardt has also come up with the term for onlies as ‘People of the “Should”’. By this he means that they have an overarching sense of right behaviour, which is one of their strongest characteristics. He notes that the word ‘should’ occurs frequently in their sentences, and they lean upon conscience to determine their moral stances.

In popular culture, what do The Exorcist, Batman and Superman have in common? Yes, they were all conceived of and act as onlies.

What do all these people have in common: Leonardo da Vinci, Isaac Newton, Mahatma Gandhi, Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Elton John, John Lennon, Iris Murdoch, Jean Paul Sartre? Yes, they were/are all onlies. No doubt a rival respectable list could be compiled of those who were/are not. Nevertheless, it is impressive.

Ann Laybourn in her 1990 book Children and Society3 found that:

Despite the fact that they tended to come from less advantaged backgrounds only children performed similarly or slightly better than those from a two-child background on behavioural and educational measures.

This ties in with Pickhardt’s emphasis on ambition as a key characteristic. He believes that the only child, having only the parents to measure up to, assumes equal standing with them, adopts equal performance standards, and strives after equal competencies as well. The role of parents in setting even higher standards for their sole offspring is a further crucial factor. Pickhardt quotes a mother as saying:

Many parents have vicarious dreams for their children, but parents of only children have epic visions.

and an advice columnist of committing herself to the following revealing statement in a letter to her daughter:

I am still your mother and it is MY responsibility to see that nothing spoils my masterpiece.

It is hardly surprising, then, to find an only child such as Jean Paul Sartre (in his autobiography Words4) rising to the challenge:

It is not enough for my character to be good. It must also be prophetic.

Of all the apologists for onlyness, Pickhardt is by far the most specific. There are few aspects he does not cover, and his text is full of thought-provoking observations. Take this one, for example:

The critical effect of having no siblings is not that the only child is deprived of a big happy family and suffers from missing the good feeling companionship with other children at home. The critical effect is that the only child is deprived of a big unhappy family, not all the time, but enough of the time so that the ups and downs of intermittent unhappiness, with siblings particularly, are not experienced as a normal part of family life.

If academia is one area in which only children are seen to at least hold their own, creativity is one where they have the opportunity to excel. Having the time and space to explore themselves and develop their talents may prove a real advantage, and can lead to setting ambitious standards. This may stem from the opportunities for daydreaming that aloneness provides; many only children speak of populating their childhoods with fantasy creatures, people and even whole worlds.

‘The Handless Maiden’ is a Grimm’s Fairytale in which the girl’s father, tempted by the devil, and driven wholly by materialist motives, cuts off his daughter’s hands. She leaves home and wanders in the forest. A king finds her eating the fruit from a tree in his orchard. He doesn’t penalise her because he falls in love with her; he gifts her silver replacement hands. She bears his child, but, just as at home, when she was handless everything was done for her, at court she lives a life of enforced idleness. Again she escapes to the forest, this time with her baby. She is bathing the child in the river when her silver hands get wet. Her actual hands are restored to her.

This has been interpreted as a story about the only child exercising creativity in adversity. Jungian analysts have seen it as an archetypal fable of the Journey of the Self. The hands symbolise her taking hold of her life, and the restoration of them to her in place of the false ones means she has been enabled through her actions to connect inner and outer worlds.

Of course many writers of prose and poetry have reflected onlyness in their work. This is particularly true of autobiographers. It is interesting to compare two of the latter who have both boldly entitled the story of their lives An Only Child and The Only Child respectively. These two writers are Frank O’Connor5 and James Kirkup6