5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

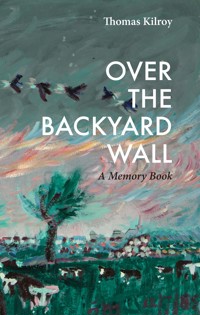

According to Thomas Kilroy, his captivating memoir materialized in response to a cataract operation in 2006, shocking his memory into being and imparting him with a uniquely tactile and sensuous perception of his own past. Over the Backyard Wall describes a coming of age embodied by escape, self-discovery and a struggle to contend with the rigid culture of a small Irish town in Co. Kilkenny during WWII, with parents representing both sides of the civil war conflict of the 1920s. He describes encounters with fellow Kilkenny artists Tony O'Malley and Hubert Butler, and writers such as Flannery O'Connor during his tour of the southern US states in the 1950s. In keeping with Kilroy's previous works, Over the Backyard Wall utilizes the silences of the past to liberate the imagination, making use of social and political history to reinvigorate the shard-like nature of his own narrative memory.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

over the backyard wall

thomas kilroy

the lilliput press

dublin

Dedication

For Hannah May and Julia

Epigraph

It happens mostly in old age, when our personal futures close down and we cannot imagine – sometimes cannot believe in – the future of our children’s children. We can’t resist this rifling around in the past, sifting the untrustworthy evidence, linking stray names and questionable dates and anecdotes together, hanging on to the threads, insisting on being joined to dead people and therefore to life.

Alice Munro,The View from Castlerock

1. The Eye of Memory

I have been asked more than once to write a memoir and I’ve always had to say no, I couldn’t do it. I could scarcely remember what happened the previous week, never mind the distant past, at least with any degree of accuracy. Then, in 2006, at the age of seventy-two, something odd happened to me – rather, something routine occurred – but it had an odd result. I had cataract operations in both eyes.

The new sight was remarkable in itself, as people said it would be, but the effect on my memory was startling, even unnerving. I began to see memories as something directly in front of me, not something behind in the past. These images were not in any continuous chain of happenings but in vivid shards, splinters, sometimes with missing details so that, at times, I wondered if I were losing it.

John Berger, in his beautiful little bookCataract(2011), describes this lack of continuity in which individual images out of the past present themselves after a cataract operation. They appear as discrete singularities. It is as if conventional, continuous narrative had been lost. I had exactly this experience myself but it was only after reading Berger that I began to understand the kind of book that I was trying to write. I have called it a memory book but I should try to explain the different approaches I have taken towards memory.

Yes, it includes a memoir of a boy growing into manhood in a small Irish town, Callan in County Kilkenny, in the years between World WarIIand the 1960s. But it also includes reflective passages, essay-like pages on different subjects that have a connection to the town of Callan or to my own life. This is the perspective of an elderly writer looking back upon his life and trying to fill gaps in the narrative. There is social and political history as well because this is the only way in which I could understand the place in which I found myself. The book is also about escape, self-discovery, the struggle I had to contend with the rigid culture surrounding me as a child. When I think of this escape I see the figure of a little boy, with scabby knees and bad eyesight, clambering over the backyard wall of our house in Callan and into the fair green behind it, a green place of games and play and the release of the imagination.

This is a mixed bag, indeed, but there is more. Almost everything I have written in fiction and for theatre has had a basis in history. My imagination is particularly drawn to missing details in the record, reinventing what might have been but for which there is no evidence. I have included two sections of historical fiction in this book because they supplement the other records of the past and expand my sense of pastness. It was the most natural way to convey the trauma of the town before two large invasions from without: the Cromwellian siege of the town in the seventeenth century and the German impact on the area in the aftermath of World WarII. Historical fiction is another avenue of retrieval and is intimately related to memory. It is, in fact, an imaginative imitation of the process of memory. It can also provide a corrective to memory when the two are laid alongside one another as they are here. For me, this layering adds nuance and cultural depth to the book. Laid side by side, the putative facts of childhood and the fictional recreation of the past play and reflect upon one another in different ways.

There is the hazy romanticism of myself and my pals with our wooden swords playing Cromwell on Cromwell’s moat in the Callan fair green. Placed beside this now is the brutal realism of the siege itself, the savagery of war and its blank indifference to the suffering of individuals. The imagination amplifies what memory has to offer. It also challenges memory. One of my discoveries in writing this book was precisely the degree of incompleteness in my own memories and the way in which my imagination kept intruding, perhaps even to the extent of creating error. Have I imagined this or did it really happen? In this way physical reality can become as evanescent as dreams.

Memory, however, also has a firm grounding in the physical. Perhaps it is the connection between memory and sight, memory and the physical eye, the actual organ of sight itself. Memories are often highly tactile, as if one can reach out and touch the remembered surfaces.

Berger gives an example of this physicality in his book: the astonishing appearance of colour, in a pristine light, after his cataract operations. In his case the dominant colour was blue. In my case the dominant colour was red. I suddenly saw, as if I were a little boy again, the deep red, painted floor of our kitchen in Callan with my mother in her apron, working away to one side.

Berger also saw his mother in her kitchen. What interests me at this point, however, is what he has to say about the connection between sight and memory. As you might expect from someone who was an expert in visual art, the analogy that he uses is of being inside a painting of Vermeer. The clarity he experiences here is a form of visual rebirth; a veil of forgetfulness is lifted and perception has been cleansed and renewed: ‘The removal of cataracts is comparable with the removal of a particular form of forgetfulness. Your eyes begin to re-remember first times. And it is in this sense that what they experience after the intervention resembles a kind of visual renaissance.’

I have no idea how this very physical procedure on the eye can have such a dramatic influence on the area of the brain that controls memory. When I tried to express my confusion on this to my very patient eye doctor, she said to me that I was talking to the wrong doctor!

A cataract operation is like having a damaged limb replaced with a new one. This is what actually happens in cataract surgery: the damaged lens is replaced by a new, prosthetic one. My eye doctor assured me that the machine for calculating the adjustment of this new, man-made lens was capable of creating one with an accuracy not found in nature. I was told that I would never have to wear glasses again except when reading. Suddenly a lifetime of heavy spectacles was lifted from me. Each year the glasses became heavier and heavier. Each year the lenses were thickened in a bid to keep up with my failing sight. My nose became grooved with this weight. But even the relief from this was as nothing compared to the effect on my memory. My memory was restoring to me a physical reality that I thought had been lost for ever.

The first memory shock after the operation had this tactile physicality that was both shocking and threatening. It had to do with my right eye which was the stronger of the two. One of the traumas of any eye operation is the fear of losing one’s sight. Indeed, I am sure that most people with eye problems have an inordinate sense that the eye is a particularly fragile organ, which is simply not true. It is, on the contrary, remarkably robust.

Evolutionary biologists tell us that this amazing organ is the product of hundreds of millions of years of evolution. What is striking about this evolution is that, despite the miracle of sight, the design of the eye itself is haphazard, back to front, as it were. Perhaps this is the subliminal source of our fear of injury? My fear is certainly neurotic. To this day, for instance, I cannot actually touch my eye with a finger. Contact lenses were never an option.

Here is how the American neuroscientist Stuart Firestein describes the physical process of seeing in his remarkable bookIgnorance(2012):

The retina, a five-layered piece of brain tissue covering the inside of the back of your eye-ball, has been dubbed a tiny brain, processing visual input in a complexly connected circuit of cells that manipulate the raw image that falls upon it from the outside world, before sending it along to higher centres of the brain for more processing until a visual perception reaches your consciousness – and all in a flash of a few dozens of milliseconds.

Perhaps because of my obsession with sight, one of the most shocking moments in theatre is the blinding of Gloucester inKing Lear. The old man tied in the chair has his eyes plucked out in a scene of terse brutality.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a staging of the scene to match the terrifying impact of the language on the page. There is hysteria in the writing, the hysteria of two sadists about to feed their appetites on the destruction of the pulsing organ of sight, the ‘vile jelly’ of the eyeball. It would be extremely difficult to match that writing with a comparable stage action without sinking into mere sensationalism or the banal. Perhaps the nearest that I have experienced such a congruence of language and action in a production of this scene was not in Shakespeare at all but in a mechanized production of Edward Bond’s playLear. A machine on stage matched the horror of the language. On the other hand, the problems I have had with productions of the Shakespearean scene in the theatre may not in fact be theatrical at all but related entirely to my own obsession with the physical eye.

I was born with a squint, what, in those days, used to be called a lazy eye. The idea being that, in childhood, one eye gave up trying and the ‘good’ eye had to take up all the slack. The ‘bad’ eye, meanwhile, turned inwards in a kind of lazy, helpless surrender, a giving up of its function of looking straight ahead.

In my childhood, the home-made solution to this problem was to cover the ‘good’ eye with a black patch, thus forcing the ‘bad’ eye to sit up and take on its proper responsibilities. I have no idea whether or not this had any benefit or was even good medical practice. What I do remember was my mother stitching a black cloth cover around the right-hand lens of my heavy glasses at home in our kitchen in Callan.

I must have been six or seven years old. The brothers and sisters said I looked great. I knew I looked like a walking bad joke. Thus encumbered, I set out, wobbling, to join my pals outdoors. Those wearing spectacles were always called ‘four eyes’. I can’t remember the insulting name that the other boys thought up to catch this vision of myself and my black patch. Popeye?

This first memory after my operations is really about a Raleigh tricycle. As with many of these flashes of memory that I now have, there are bright colours, blues and silver and black, a beauty of metal that, even in memory, I feel I can touch in its coldness. There is also the memory smell of oil and leather, saddle and saddle bag, the pristine pedals awaiting the push of the foot, the irresistible bell on the handlebars awaiting the tinkle, the flash of the spinning wheels as this beautiful thing shot forward.

It was after Christmas and there was the run-out into the brisk open air to show off the presents from Santa Claus, theBeanoandDandycomic book annuals, a whole year of reading which, alas, we had finished before the week was out. There was the tang of the new books, the smell of glue on the spine holding together the highly illustrated covers, the odour of fresh ink, print barely dry, it seemed.

Boxed games of Ludo and Snakes & Ladders, toy trains and fire-engines, black cardboard rabbits with bow ribbons tied around their necks. Each rabbit had a stopper on its bottom. When you pulled out the stopper a flow of sweets in their coloured papers cascaded into the palm of the hand.

My best pal John Moloney got the tricycle. I never connected this glittering present to the fact that he was an only child and that there were ten of us in our house. But I remember my envy.

Heavy glasses and black eye-patch forgotten for the moment, I was up on the tricycle. I can still remember the first moment of pushing the pedal and feeling the power running through the tricycle from my feet. I’m off! To help me along, John was pushing from behind, faster and faster, one leg up on the bar between the two back wheels, one leg hopping, pushing away the ground behind him as we sped off, screeching.

Outside their house was this foot scraper, two upright metal bars with a crossbar between them like miniature rugby goal posts. You put your foot on this crossbar and scraped the dirt off the sole of your boot before entering the house.

When the front wheel hit the scraper I flew over the handlebars. I landed face down on the scraper, one of the upright bars hitting my right eye and its patch. When I staggered up, screaming, the blood was pouring out from beneath the black patch.

There was much running and shouting so that when I staggered across the road towards home, holding my bloodied eye and smashed glasses, my mother was already in our front doorway, a hand to her mouth. She fainted at the sight. My mother frequently fainted under stress, although there were times with my father when she seemed to use this fainting as a weapon in the struggles between them. On this occasion, neighbours came running from other houses on our terrace to pick her up by the door. Someone was sent racing up the road for Dr Phelan, to see if he was in his surgery.

Glasses were glasses in those days, not plastic. Only later, as everything subsided and the eye was bared to the light, it was discovered that, in holding the broken glass in its cloth bag, my mother’s black patch had saved the sight of my right eye.

2. Over the Backyard Wall

Bless ’em all, bless ’em all,

The long and the short and the tall,

Bless de Valera and Seán MacEntee,

They gave us the brown flour

And the half-ounce of tea.

I was a child of the Hitler War. That old, mocking song about efforts at wartime rationing by members of the Irish government, itself a parody of a famous World War I British army singalong march, rang through my childhood. When World War II started in September 1939 I was just a few weeks short of my fifth birthday. But, where I came from, the real news that month was not the outbreak of war but the All Ireland Hurling Final in Croke Park on the third of September between Kilkenny and Cork, the black and amber striped jerseys of Kilkenny against that vivid red of Cork.

Callan is almost on the Tipperary border, which meant that it was also on the border between two competitive hurling provinces, Leinster and Munster. On the streets of our town we lived out that old hurling rivalry between Kilkenny and Cork or Kilkenny and Tipperary. From across the Tipperary county line, the boys from Mullinahone would cycle into Callan after a Tipperary or a Cork win and raise hullabaloo in the pubs to taunt the defeated locals.

On that dark Sunday in 1939, a few days after the start of war, Kilkenny beat Cork by a single point in the All Ireland Final in Dublin. In keeping with the apocalyptic mood of the times, a severe thunderstorm broke over Croke Park in the second half of the match. It was said that Jimmy Kelly from Carrickshock took off his boots and socks and in his bare feet sent over the winning point for Kilkenny. But it was also said that few could see him through the torrential rain.

On the morning of the match the Dáil (or Irish parliament) had rushed through the Emergency Powers Act, which effectively gave Ireland its controversial neutrality in the war. In a typical Irish deployment of the English language the war years were known as The Emergency, although whose emergency exactly was never quite specified.

High up on a cement wall of a building in the centre of our town was a half-moon of lettering with the wordsCallan Town Hall. This was covered with canvas throughout the war. We children were told it was ‘camouflage’, to drive astray any bombers that might just happen to be passing overhead, unable to see that they were over Callan. The canvas stayed there for years after the last shot was fired, a forgotten remnant. During the war we looked nervously at the sky as we walked back and forth to the Christian Brothers School on West Street or, earlier in life, when we trooped to the Convent of Mercy School at the end of Bridge Street. Not a plane in sight.

There were ration books with detachable coupons to hand over to the shop in return for the rationed items. And there was, inevitably, black-marketeering, particularly of petrol and tea. My father was the local police sergeant. Like many policemen, he had a complex relationship with those who broke the law, a kind of intimacy, I suppose, out of a shared interest in transgression. I remember each Christmas during the war the arrival of an unexplained parcel at the house from one of the town’s shopkeepers. It contained tea, sugar and other supplies. All from the black market. Payback, no question about it, to my father, but for what service he had rendered to the lawbreaker I can only guess.

My mother was a strict Catholic but, to my surprise, she had no difficulty accepting such largesse. It was one of my first encounters with the elasticity of Catholic morality, something that bothered my logical mind in childhood. There seemed to be always occasions when priests and laity could turn a blind eye to actions that were clearly questionable.

My father read theIrish Pressnewspaper each evening at the head of the kitchen table. Around the table my brothers and sisters and myself could see black arrows on simple maps on the front page of the newspaper marking the progress of armies across Europe or North Africa. The war was out there and far away.

I also remember that when we went to the matinee at the local cinema on a Saturday afternoon, the burly owner, Bill Egan, in his kiosk would (only sometimes, it has to be said) look closely at us to see who we were and then wave our few coppers away with his hand, saying, ‘Pass along! Pass along!’ Why we, as children of a policeman, were allowed in free remained a mystery to us. Bill was one of the town shopkeepers who could supply you with oil and petrol if you were stuck, although there were very few cars in the area at the time.

Sometimes our father listened, late at night with some of his pals, to Lord Haw Haw on the wireless. This was the nickname of William Joyce who broadcast in English for the Nazis in their elaborate propaganda machine. My father, from Galway himself, took pride in the fact that Joyce also had West of Ireland connections. As an ex-IRAman, my father had an almost natural anti-English feeling which he shared with his cronies in front of the wireless.

In the dark from our beds upstairs we children heard the nasal, mocking voice of Lord Haw Haw: ‘Germany calling! Germany calling! And now this is your commentator on the news, William Joyce.’

Nearly half a century later I was to write a play,Double Cross, for the Field Day Theatre Company, about that voice. The play came directly out of the memory of my father and his friends loudly debating the imminent defeat of Britain downstairs in the kitchen.

Our own defenders, the Local Defence Force (LDF) and the Local Security Force (LSF), would parade on special days like St Patrick’s Day. They were always accompanied by the local unit of the St John’s Ambulance Brigade, led by the local chemist, Mick Bradley, all kitted out in their smart grey uniforms, with round tin helmets emblazoned with scarlet red crosses. ‘Will ya look at the chamber pots on their heads!’ our ample neighbour Mrs Barry would say, leaning over her front wall on Green View Terrace.

We had our brief taste of the real thing, too, when a large contingent of the Irish army camped out around the town on the way to manoeuvres by the River Blackwater in August 1942. General MacNeill and General Costello squared off before one another in a mock battle there in the one serious exercise of the army during the war. Everyone was proud of the uniforms and guns and the neat rows of tents in the fields of Westcourt outside our town, convinced that we were ready to take on anyone, Jerries, Tommies or Yanks. But it was to be another army from another time, that of Oliver Cromwell, which really took hold of my imagination as a child, staying with me to the present day. Cromwell had left his mark on that field over our backyard wall.

Callan was what used to be called a market town with somewhere between one and two thousand inhabitants. In other words, it had no indigenous industry as such but provided services for the local farming community. Indeed, I remember it as having a kind of money-free economy with a lot of ingenious improvisation going on between the mothers to get through the week, an orange ten shilling note borrowed here, a few half-crowns borrowed there. Lines of carts, pulled by horses or donkeys, passed our front door each morning with churns of milk for the local creamery. On their way back, they carried skimmed milk for the calves at home.

My mother had a deal with a local farmer, Pat Delaney of Coolagh, where she filled a bucket from a churn of skimmed milk from his cart and occasionally bought a pound of butter at the creamery. Pat did the buying for her. She used the skimmed milk to bake delicious soda bread and currant buns and, more surprisingly, as a wash to bring up the bright red of the painted floor of our kitchen.

Behind our house at Number 4 Green View Terrace was a narrow backyard. Each of the ten houses on the terrace had one. The walls were high enough to prevent prying, so that our mother had to stand on an upturned butter box or galvanized bucket when she wanted to gossip with jolly Mrs Barry next door.

That backyard was the first place of confinement from which I had to escape. Physical places become part of our imagination as we leave them behind. When they are left behind, they take on new, imagined shapes with only a partial connection to the original. Spaces of wonder, curiosity and surprises. Spaces to be negotiated and renegotiated, walls to be climbed in the discovery of somewhere else.

If this is to be a memory book, it is also a book about a writer in his eighties playing with those memories and trying to see how this past might become usable in writing. Maybe this is another reason why fiction bleeds into the memories in this book, why I have to invent as well as remember.

I am also trying, in my final years, to make even partial sense out of personal obsessions or phobias. Top of that list would be my detestation of all things military, including the absurdity of even wearing uniforms. Is this connected to the fact that my father was a policeman?

At the end of the backyard was the outdoor lavatory, this being before we had a local sewage scheme in Callan. It was a dry lavatory with a deep pit to hold the human waste. Every so often a man came with a stinking cart to empty the cesspits behind the terrace.

Plumbing may protect us from disease. It is true that diphtheria, for instance, was endemic in the Callan of our childhood before we had a sewage scheme. Each spring came the inflamed, dreaded white spots in the throat followed by the choking, swabbing, and the roulette of tests. One negative in three tests and you found yourself in the strictly quarantined fever hospital in Kilkenny.

I have a memory of that same fever hospital, which had to do with yet another deadly infection of the time, scarlet fever (scarlatina). My memory has the selectivity of memories from childhood, a highly polished wooden floor, nothing more, with the posh smell of heavy floor polish.

The scarlet fever infection seemed to have hit our household like a wave, taking several of us at once. We children, how many I cannot remember, were standing on one side of the polished floor of the hospital with our mother, surprisingly, beside us. I say surprisingly because my memory is that she wasn’t infected but had been allowed into the place to help in our care. Could this have been possible in a quarantined hospital? I have no idea but I know she was there. Across the polished floor, a great distance away, it would appear now, our father crouched upon one knee with our eldest brother standing beside him, a safe distance away from our itching bodies and inflamed faces. Our father had a brown paper bag in one hand. He took oranges, one by one, from the bag and rolled them, like a player in some exotic game, across the floor in our direction.

It must have been post-war since neither oranges nor bananas appeared in Callan until after the war. Indeed, I remember being instructed in how to peel a banana at the time, a comical fruit if ever there was one, before eating it.

Plumbing has also protected us from the constant reminder of the ramshackle, internal arrangements of the human body. There was no such protection from shit in my childhood. I can still see that cloacal man on his filthy cart, a figure out of a Dickensian nightmare, carrying away the waste from behind the terrace. Even as a child I think I had some sense of the ambiguity of his service, hovering between cleaning and reminding, doing something which no one else would do, amemento morihigh up on a foul cart.

Over the backyard wall was the expanse of the fair green. It gave its name to Green View Terrace, where our house was, which, as the name implies, had some aspirations to gentility. The terrace stood on a hill above the town and slightly apart from it, looking down on it, as it were. In the other direction it looked away south towards the Clonmel Road and the nearby Tipperary border, with the lovely feminine, torso shape of the mountain, Slievenamon, the Mountain of the Women, lying lazily across the horizon. In truth this is not a mountain at all, rather a high dome with a cairn of stones on top that gives the appearance of a nipple on a bounteous breast.

On one occasion I remember, as a small boy, a kind of Sunday outing, a picnic hike, to this gentle, modest mountain. It was like an event out of old Russia, or a scene out of a film by Nikita Mikhalkov, a cluster of families gathering for the adventure on Green View Terrace at the workhouse gate. The women were in sun hats or scarves, with white blouses and long skirts, the men in their Sunday suits, one or two with flowers in their buttonholes, and everywhere excited, crying children, a fussing and a hugging, with squeals and shouts, reminders, advice and warnings.

About ten families were involved, with sandwiches, milk bottles and plugs of rolled newspaper as bottle stoppers, Primus stoves with their cans of paraffin to make tea for the picnic on the mountain. Bags of apples and sweets, bottles of lemonade and, maybe, something stronger for the men. Ponies and traps were loaned by local farmers for the occasion. I can see the polished wood of the traps, the iron step up and the little door with its handle at the back by which you climbed into the vehicle, the cushioned seats facing one another inside. There was nothing like this mode of transport in our daily lives on the terrace.

I remember the trap that I was in was driven by a nervous Garda Jennings from my father’s police station, chosen because he was a countryman and should know about horses. There was much oohing and aahing as the pony slipped on the road passing Grace’s farmyard, past the town cemetery at Kilbride and every incline between there and the village of Kilcash at the start of the climb.

We knew the great folk tale of the mountain, of course, which had given it its name, the Mountain of the Women: how the swaggering and aging giant of Irish myth, Fionn, held a race of women to the summit to decide who should be his bride. We knew the outcome, how the wily old chief contrived to have his chosen woman, Grainne, win the race through a trick. We also knew the other story of the Fenian cycle, how the old man eventually lost his bride to the handsome young Diarmuid, the pride of Fionn’s own band of warriors, the Fianna.

You had to carry a stone, however small, to the summit of Slievenamon as part of your climb and add it to the cairn at the top. Happily we discovered that the mountain, so big from a distance, offered a gentle, welcoming slope, which even our small bodies could manage with the odd tumble.

I had a curious experience at one point during that outing, a typical intrusion of a child into adult affairs. Groups stopped here and there to take in the view, the great spread of fertile Tipperary land stretching away into a haze of greens and blues. I galloped into one such group, which included my mother, and knew at once that I shouldn’t be there. I was already attuned to this other, adult language reserved for adult matters, which always dribbled away into silence at the approach of a child. Indeed, I think I had a partial awareness already that this was a language I had to master myself in the process of growing up. Later I learned why. It was a necessary, coded language of human secrets that I had to learn before I could become a writer.

The women were standing, pointing downhill and whispering. When I appeared, they turned together and stared at me, three or four transfixed women. They saw me but only partially. They had that dazed look of people whose minds were elsewhere, somewhere frightening. They couldn’t connect that horror to the staring child in front of them, with his heavy glasses and bad eyesight. Then the moment of befuddlement was broken up and I was swept away from that place of dark mystery between the flowing female skirts.

Like so much in my childhood, I came to work out the meaning of that incident only many years later. The women had been discussing another story of the mountain, not something out of an ancient saga or folk tale, but a real event of brutal superstition, which took place at the foot of Slievenamon in a village called Ballyvadlea.

In 1895 a twenty-six-year-old woman, Bridget Cleary, was burned alive over the open fireplace of her home as a changeling, a woman possessed by the fairies. It was the last recorded incident of witchcraft in Irish history. What is particularly scarifying about the story is that Bridget was burned by her husband Michael in the company of her own relatives and neighbours. The story has attracted writers, film-makers and scholars of social history. I spent some time myself tinkering with the possibility of a play on the subject. I gave up when I realized I could not retrieve the mentality of the story. I had the narrative but not the damaged mind at its centre. I was left with crude melodrama, which would have been a failure on the stage. As I grew up and learned the full story of Bridget Cleary, I became more aware of the need to move away from such a world before I could come back to it in my imagination with some degree of composure.

The beginnings of that movement away started with the back wall of our house. Climbing over that wall into the green was for me a releasing of the imagination, an invitation to play, an escape from the everyday into a place of endless possibility. Very recently, I came to realize that, over sixty years later, I had used that action of climbing that wall in the writing of an unproduced screenplay, ‘The Colleen and the Cowboy’. I had no conscious sense that I was doing this at the time of writing, but that was what was going on.

This screenplay is set in Galway, so the scene has been moved in my imagination from one end of the country to the other. The house in the screenplay is not our house in Callan and my young hero Val is not even an alter ego of myself. His father is certainly not a portrait of my own father. But the situation is one that I lived through and the backyard wall in the script is our backyard wall of all those years ago, even if the backyard itself is different. To use something from life in fiction, you have to distort the original. Change is the beginning of invention.

Eighteen-year-old Val in the screenplay is a film buff (as I was and am myself). His playing at being a film director, directing a film of cowboys and Indians in the field behind his house, gets him into strange and ultimately life-changing adventures in the script. I remember playing such games myself with my pals on the fair green in Callan. At any rate, here is Val over the backyard wall:

EXTERIOR. BACK STREETS OF GALWAY. DAY.

Camera sweeps over narrow, cramped streets, real poverty. Rows of small, one-storey houses. A woman throwing filthy water into the street. Behind the houses a large field.VALhas set up a ‘film location’ in the field. He has assembled a crowd of smaller children, dressed as cowboys and Indians, all charging about while he ‘directs’ them.VALwears a home-made visor and old riding britches à la the great director Erich von Stroheim. His ‘camera’ is also home-made, cardboard boxes, two old bicycle wheels as film reels. ‘Filming’ in progress.

EXTERIOR. BACKYARD OF VAL’S HOME. DAY.

An angry, rough-looking workman,VAL’S DA, comes out into the littered backyard, bits of machinery, rubbish about the place. He is followed by a cowed woman,VAL’S MA, and a scatter of small children. TheDAstands on a ladder and looks into the field.

VAL’S MA(anxiously)

Is he out there?

VAL’S DA

Will ya look at that son of mine! God Almighty, what’s to become of him?

EXTERIOR. FIELD. DAY.

POV VAL’S DA: VALis still ‘filming’ when he and his ‘cast’ are shocked by his father’s roar.

VAL’S DA

Get in outta there, you blitherin’ eejit!

EXTERIOR. BACKYARD OF VAL’S HOME. DAY.

VAL’S DAis frog-marchingVAL, still trying to hold on to the remains of his ‘film camera’, through the backyard.

VAL’S DA

Ye’r goin’ to do a day’s work, me bucko, like everywan else!

VAL’S MA

Are y’as alright, Val?

VAL’S DA(to mother)

You!’Tis you has him the way he is!

VAL’Sface: despair.

I wrote all this long before I realized where it had come from. The backyard in Callan with its escape route into play had been filed away in some corner of my brain awaiting its moment of usefulness.

There were in fact two fair greens in Callan. The one immediately behind our house was theGAApitch for hurling matches. The lower one, closer to the town centre, was the fair green proper where the monthly Fair Day, of cattle and sheep, pigs and the odd horse, was held. This was also the place where the visiting circuses, like Duffy’s or Fossett’s, pitched their Big Tops. It was also the site of the annual town carnival with its dodgem cars, swing-boats and roundabouts, chair-o-planes, ghost trains and freak booths.

I vividly remember one performing act at the carnival: a small slim man in a tight black suit wearing goggles, diving from a high tower into a dangerously small tank of water. Maybe this was all the more dramatic in the darkness with spotlights from the noisy carnival generator.

The Callan Fair Day spilled out from the lower fair green, taking over the full length of Green Street in the town proper. Farmers just corralled their cattle and calves up against shop fronts and waited for the buyers to arrive in their dirty yellow butcher coats. Much yelling and spitting on palms, hand-slapping and oaths, theatrical walk-aways by the buyers and dismissal by the farmers. At this point the by-standing tangler took over. The tangler invariably looked like a tramp but his role in the beef trade was crucial. His job was to bring the two parties back together again in a deal when the deal seemed lost. At first both sides pretended elaborate indifference. There were pointed references to other, better deals up the street. But then the tangler’s persuasiveness did the trick. Hands slapped as the deal was done and the tangler pocketed a few bob from each party and moved on to the next drama.

Sometimes a bullock broke free and went galumphing down the street, to the delight of myself and other small boys. I remember one of them breaking into the staid Shelley’s Ladies & Gents Outfitters shop, a place of cloth smells and mysterious female combinations, now redolent of other, pungent smells of cow dung and piss, as the animal was hunted back out again and the screaming ladies closed the shop for cleaning.

There was a childhood routine that we followed with the arrival of each circus. Part of the excitement came from the early start of the routine, the first light of dawn, it seems to me now, tumbling out of bed and dressing in the dark. A line of children, we headed out the Clonmel Road, past Mrs Butler’s cottage, past Grace’s farmyard and the spirit house, which we knew was haunted, so we hurried our steps as we skipped by. Then, beside the wall of Kilbride Cemetery, we waited in the half-darkness until we heard the jingling and footfalls of the line of caravans and horses in the distance.

There could be nothing more exciting than the vision of that line of brightly coloured wagons, with the wild-looking circus people waving and shouting at us. Lines of piebald circus horses walked by and the odd perambulating elephant or giraffe or other exotic creature taking the air. It was like the opening of a highly coloured book there on the side of the road as we jumped and yelled, running alongside this cavalcade of promise on its way back into the lower fair green of the town.

On theGAApitch on the upper green we learned hurling in ferocious games of ‘backs and forwards’. This was a shortened version of a real match. You needed only a goalkeeper, six backs marking six forwards and two or three centre-field players out the field sending high ball after low ball into the mucky patch in front of the goal. These boys out on the field were the elegant hurlers, the kind who were sometimes referred to in my day as ‘hair-oil’ hurlers, hurlers, in other words, who were ostentatious masters of the Kilkenny style, wrists lifting a ball delicately on the end of the stick and sending it high into the air with the one graceful motion or sending it low and hard with fearful accuracy.

The rest of us laboured in the engine room of the backs and forwards. Fingers were sliced and heads opened in the fray. Iodine and hot water were dispensed in the backyard of our house as evening fell and my mother tut-tutted by the outside water tap at the state of our heads and hands. She had the hands and temperament of a nurse as cuts, which frightened us, were quickly cleaned and bandaged and we were assured that we weren’t going to die this time.