Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

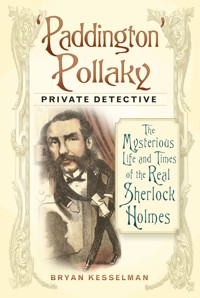

Who was the Victorian super-sleuth 'Paddington' Pollaky? In reality, he was a contradiction: a man of mystery who tried to keep out of the limelight, while at times he craved recognition and publicity. He was a busybody, a meddler, yet someone whose heart was ultimately in the right place. Newspaper accounts detail his work as a private detective in London, his association with The Society for the Protection of Young Females, his foiling of those involved in sex-trafficking, and of his tracking down of abducted children. Themes that remain relevant in the twenty-first century. What was his involvement in the American Civil War? Why did he place cryptic messages in the agony column of The Times? And why were the newspapers so interested in this Hungarian detective and adventurer while the police thoroughly disapproved of him? In this first biography of this complex character, author Bryan Kesselman answers these questions, and examines whether it was Pollaky who provided the inspiration for the literary greats Hercule Poirot and Sherlock Holmes.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 448

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Anne-Marie

Acknowledgements

Alicia Clarke – Henry S. Sanford Papers, Sanford Museum

Rosemarie Barthel – Thuringian State Archives, Gotha

Letter written by C.L. Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) reprinted by permission of United Agents on behalf of Morton Cohen, The Trustees of the C.L. Dodgson Estate and Scirard Lancelyn Green

Held by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

GEN MSS 103, box 1, folder 53

Quotations from the Toni and Gustav Stolper Collection 1866–1990 and the photograph of Pollaky courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute, New York

2010 Photograph of Paddington Green houses – Pre-Construct Archaeology – www.pre-construct.com

David Shore – image of Darrell Fancourt

Mark Beynon and Juanita Zoë Hall – The History Press

Gill Arnot – Hampshire Museum Services

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 In Hungary

2 Arrival in England

3 ‘Inspector Bucket’, Lord Lytton, Lord Derby, Lord Palmerston, the Road House Murder and Whicher

4 Marriage One

5 Pollaky Alone

6 Confederate Correspondence

7 Marriage Two

8 Sir Richard Mayne

9 1862 Naturalisation Application – ‘It would be monstrous’

10 The Casebook of Ignatius Pollaky

11 An Interview with Pollaky

12 Dickens, Lewis Carroll, W.S. Gilbert, and others

13 Retirement

14 Naturalisation

15 Death

Appendices

i ‘Small-Beer Chronicles’ (Dickens)

ii ‘The Agony Column’

iii ‘Polly Perkins of Paddington Green’

iv The Colonel’s Song etc. (Gilbert and Sullivan)

Bibliography and Sources

Plates

Copyright

Introduction

Some time ago I was driving my car on the way home from a singing engagement, singing the Colonel’s song from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Patience to myself. This involves a long list of people of the type to make up a ‘heavy dragoon’, and includes the name ‘Paddington Pollaky’. I couldn’t remember who he was – I had known once. I decided to check at the earliest opportunity. Who would have guessed that this would lead me to write an opera about him as well as this book?

My initial researches led me to look at the ‘Agony Column’ of The Times. Here was subject matter for musicalisation. Why not write an opera about the mysterious people who advertised there? What if Paddington Pollaky, who was one of them, was an important character in the piece? What if he were the main character? I began to work out a plot. This involved a certain amount of research into his life. I gathered a huge amount of facts, some of which had not been examined much before, and certainly not placed in juxtaposition with each other. It seemed that a biography was inevitable. There were frustrations as well as successes, and you will read about some of them in the following pages. I have tried to find original sources for everything, and not to rely only upon rumour and tradition. Where there is doubt, I have indicated it.

An investigation into Pollaky and his life must necessarily be hampered by the fact that he destroyed all his case records. Nevertheless, plenty of material exists, buried away in newspaper and court reports, and hidden in archives in various cities. Among these are a number of documents, which, if not of huge historical import, lend a new colour to certain famous events of the past.

He was a fascinating character. Described variously as Detective, Private Investigator, and Adventurer, he was also an Alien Hunter (aliens of the foreign kind), and evidently something of a busybody, but one who seems genuinely to have had the best interests of others at heart. He himself often felt frustrated at the stubbornness of some of those around him – but more of that in its place.

W.S. Gilbert mentions Pollaky in three of his dramatic pieces – No Cards, An Old Score, and most famously, Patience. Even Charles Dickens and Lewis Carroll wrote about him. You can read about these references in Chapter 12 and in the Appendices.

My voyage of discovery has taken me to a number of archives in London; involved numerous emails and letters to archives and copyright holders in England, America, Germany, and Slovakia; and involved a trip to Bratislava in an attempt to uncover any little detail of Pollaky’s early life which might remain in his birthplace.

I have quoted letters, newspaper articles, and reports at length, preferring to let Pollaky and those who wrote about him speak for themselves, but I have added commentary as guidance to these passages when necessary. Many of the items can be read as stand-alone short stories, worthy of dipping into, although I hope that the reader will make an effort to get to know this unusual man by following his story in its entirety. The book almost follows a chronological order, but inevitably if one wishes to follow the threads of a life in a connected way, some concessions have to be made. Being naturally averse to endnotes, and in particular to wretched jargon (e.g. ibid. and loc. cit.), I have included information that might be put there in the body of the text. There is, however, a comprehensive bibliography at the end. All transcriptions of handwritten letters were made by me (except for that of Lewis Carroll). I have not indicated pagination in those letters, nor have I kept the original number of words per line.

But firstly to Mystery Number One – who was Ignatius Paul Pollaky?

In 1909 George Routledge & Sons published a book by James Redding Ware called Passing English of the Victorian Era. The following definition appears on page 185:

O Pollaky ! (Peoples’, 1870). Exclamation of protest against too urgent enquiries. From an independent, self-constituted, foreign detective, who resided on Paddington Green, and became famous for his mysterious and varied advertisements, which invariably ended with his name (accent on the second syllable), and his address.

This definition by no means tells the whole story, but it’s a start. ‘Peoples’ 1870’ refers to the origin of the expression (a slang word of the man in the street), and the year it came into use. We learn that ‘Pollaky’ should not be pronounced as Pollaky (as in the song from Patience) but Pollaky, with the stress on the second syllable. Ware is wrong on one count, though: Pollaky did not invariably finish his advertisements with his address (and, who knows, may not always have used his name either).

Bryan Kesselman, 2015

1

In Hungary

Pressburg, Hungary, 1838. Summer – late afternoon. School over, a 10-year-old boy and two friends climb in and around the castle ruins that look out over the Danube, its high walls dominating the view of the city from the other side of the river. Their chatter is all nonsense, of course, to everyone but themselves; and their shrieks of laughter as they imitate their teacher who talks through his nose and is often angry because the class doesn’t pay attention in these hot days, echo around the castle walls. Then, suddenly, a woman’s voice calls, ‘Ignatz, come at once, your father wants you to carry his violin.’

‘Coming,’ he calls.

‘Just look at your clothes! Go and change at once, don’t let your father see you like that.’

And so on. Is this a possible scene from the boyhood of Ignatius Paul Pollaky? So few details exist of his early life in Hungary, that I have made this up. All that follows, however, is fact. In this chapter, I have detailed a little of the detective work I attempted in my efforts to uncover previously unknown facts.

In 1914, Ignatius Paul Pollaky applied (for the second time) to become a British Citizen. He told Detective Superintendent Charles Forward of the Brighton Police that he was born in Pressburg (Pozsony), Hungary, on the 19 February 1828.

His father was Joseph Francis Pollaky, a Common Councillor according to his 1861 Marriage Certificate, or a Private Correspondent and Musician according to his 1914 naturalisation papers as recorded by Detective Superintendent Forward.

Had Joseph Pollaky been accorded the honorary title Regierungsrath? This title nominally denotes a government official, but in countries ruled by Austria, as Hungary was at that time, it was a title awarded for meritorious services which might equate with ‘common councillor’. Ignatius’s mother was Minna Pollaky; both parents were Hungarian subjects. Pressburg is now called Bratislava, and is the capital city of Slovakia. It has had a number of names over the years, often with alternative spellings: Posonium, Pisonium, Posony, Pozsony, Presburg, Preßburg, Pressporek and Poson are examples. The name Bratislava has been in use since 1919, the year after Pollaky’s death. As you will read later, in 1863 he went back to Pressburg during an investigation, and would surely have visited his parents if they were still alive.

According to the announcement of Pollaky’s 1861 marriage his father’s middle name was François, and the Pollaky family address in Pressburg was Old Castle Hill. The castle is on a hill, but there is and was no street name that exactly translates in that way. Of course, it is possible that he simply meant that they lived on the side of the hill upon which the old castle stands. From 1811, after a disastrous fire destroyed it, until 1957, when restoration work began, the castle was in ruins, a shell, and that is how young Ignatius would have known it. One might imagine him, as suggested above, wandering around the ruin, and gazing out over the Danube to the land that lay south of the river and beyond.

The spelling of these names follows English conventions, and it is more likely that father and son were in reality Josef Franz and Ignatz or Ignaz Pál Polák(y). The surname Pollaky is fairly uncommon, so much so that it is tempting to make use of all sorts of scraps of information, even if they lead nowhere. What, for example, should be made of a letter written from Vienna (in German) in 1868 by a married lady called Julie Pollaky to Sir George Airy, Astronomer Royal in England, in which she asks for any information he might have about her brother? Her brother, August Weiss, bears little connection to this investigation, nor does she – but her husband is possibly a member of the Pollaky clan. (In the event, Airy replied, in English, that he knew nothing of the lady’s brother – and there the matter rests, we don’t know why Julie Pollaky thought that he should know anything.) Of more interest, perhaps, though still as mysterious, is a notice printed in Budapest (also in German) in November 1885 announcing the death of one Fanny Modern, whose maiden name was Pollak [sic]. Among the mourners listed are Ignatz Pollaky, brother, and Marie Pollaky (relationship not listed).

Finding information about Pollaky’s early life proved extremely difficult. Were the Pollaky family in Pressburg comfortably off? What was their religion? Polak, Pollak, Pollack etc. are often (but not necessarily) names of Jewish families. On the other hand there are baptismal records in Slovakia from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries showing a small number of Pollakys who were Roman Catholic. The surname implies that a male ancestor was from Poland. He was married twice after he arrived in England, both times in a (Church of England) church ceremony, and all his children were baptised. What did his family and friends call him? – Ignatz, Ignatius, Paul, or perhaps Náci (which is a shortened version of Ignatius). The last is pronounced na:tsi, which now has other connotations but did not then.

First theory: since I found no records of an Ignatius Pollaky (or variation of that name) born in 1828, or in the years either side, in Bratislava, Slovakia, or any part of what was Hungary or Austria, I contacted a genealogist based in Slovakia who suggested the following was a possible match: on 1 May 1829 a child was baptised at the (Roman Catholic) Blumentál church in Pressburg under the name Franciscus Polák. His father was also called Franciscus Polák and his mother Maria Polák (née Woszinger). All first names were written in Latin, and so it seems likely that Franciscus Polák was in reality Franz. It seemed quite possible that Minna (Pollaky’s mother’s name) might be a diminutive of Maria. Could it not be that the child was baptised with his father’s name though he might grow up known by another?

But I did not feel satisfied with identifying this Franciscus Polák with Ignatius Paul Pollaky, and so as not to leave a stone unturned, I decided that it was necessary to make a visit to Bratislava, the one-time Pressburg, the city (now in Slovakia) in which Pollaky claimed to have been born. A brief record of my visit follows, leaving out most details that are not relevant to my researches. My discoveries, or lack of them, will become clear. One thing is certain, though: I walked in places where the subject of this book walked as a child and young man, and saw buildings that he must have seen.

Sunday, 6 April 2014

The plane landed at Vienna Airport at 10.30 a.m. The bus to Bratislava took only one hour. There was no border control as we entered Slovakia.

In the afternoon I walked to Bratislava Castle. Entry was free, but it cost 2 euros for permission to take photos inside. The castle has been beautifully restored from the dreadful ruin it was, with white plastered walls inside and out. But the place is incredibly sterile as a result. The souvenir shop had nothing to recommend, but the old books – calendars and almanacs – displayed on the top floor of the castle museum were interesting.

Monday, 7 April

I left the hotel and began to walk towards the Slovenský Národný Archív, Drotárska Cesta (Slovak National Archives) – a long walk. I eventually managed to board a 207 bus which took me most of the rest of the way. The remainder was then uphill and downhill: a hot sun and a cool breeze.

I arrived at the archive building at 9.30 a.m. They found a young lady who spoke English quite well. With her and two Slovak speakers we were able to establish that they would have no information relevant to my researches there. They thought at first I was after records from 1928 and were surprised when they found they were 100 years out. But they were able to direct me to two more archives in Bratislava. By 10.30 a.m., when I left, the sun was stronger and the breeze weaker. I returned to the city centre. The Old Town is very pretty, though there is too much graffiti.

At noon I arrived at the second archive: Štátny Archív, Križkova 5 (State Archives). The two young men I met there were also very helpful. They spoke little English, but managed to tell me that it was now lunchtime and that their colleagues were now all out. They recommended the third archive as recommended by the previous one. But they took my email address and a photocopy of a page in a Bratislava guidebook I had found in the hotel which mentioned Pollaky.

Tuesday, 8 April

I took a taxi to the Archiv Hlavného Mesta SR Bratislavy (Bratislava City Archives), Markova 1. The lady I met there spoke Slovak and German. We used the latter to communicate with, and that proved most satisfactory. She knew nothing of the name Pollaky, only Polák and Polágh, and found a copy, in Slovak, of the reply to an email I had sent to the archive which translates as follows:

In respect of information about a family named Pollaky, who allegedly lived in Bratislava around the year 1828 we inform you that in Bratislava there is no such name. At that time they lived several families named Polak Pollak Polagh etc. (but not the name Pollaky). We have no directories or census of inhabitants for the given year in our archive. If you wish to consult the archival documents, the archive reading room of the Bratislava City is open to the public from Monday to Thursday.

And this despite the fact that I knew the name Pollaky had existed. I filled in a form on the subject of my researches, which she kept. She then brought me a huge old tome with births of children in the Blumentál Church area entitled RodnýIndex Nové Mesto Blumentál 1770–1888. (I had mentioned finding details of Poláks mentioned in records of that area.) I read there of births with no other details except years. Could one of these be Ignatius – Josephus Polák born 1827, or Franciscus Polák born 1830? They seemed vaguely possible.

She then brought me a print-out from the Mormon Family Search website which listed the baptism of an Ignatius Polák on 31 July 1819 – Father: Josephus Polák, Mother: Marina Vincek.

I pointed out that 1819 was nine years too early, had this been the man I was after he would have been ninety-nine when he died – just about possible, I supposed. Had he therefore lied about his age to make himself appear younger than he really was? I wouldn’t put it past him; vanity might be the explanation. My helper then suggested that the Ignatius Polák listed might have died as a child, but that the parents had another son later to whom they gave the same name. Such things are known to have happened, but there are no records to confirm this.

This family lived in Malacky, some twenty-two miles north of Bratislava (Pressburg), but close enough for someone to claim that they came from the more impressive place; after all, my grandfather was born in the little village of Przedecz in Poland, but often claimed he was from Warsaw. It was also possible that the family had moved from Malacky to Pressburg before the next son was born, or, if Ignatius Paul Pollaky had been born in 1819 in Malacky, and baptised there in the Kuchya church, they might have moved to Pressburg when he was still an infant.

After lunch I visited the Bratislava Museum of City History. I learned there that the Jewish Quarter (now largely demolished) was below the castle area, and this would have been on the side of the hill. This is relevant if one considers the possibility that Pollaky may have been Jewish by birth. There are no Jewish Pollakys listed anywhere, but there were Jewish families called Pollak living in Bratislava, as I discovered by contacting people listed on JewishGen website who were researching that name in that area, though I found no likely Jewish connection at that time.

Second theory: Ignatius Paul Pollaky may have been born Ignatz Pál Polák in 1828, and baptised with the name Ignatius; the younger brother of the then deceased Ignatius Polák baptised in 1819 in Malacky, born there or in Pressburg if his family had moved there by the time of his birth. Josephus Polák and Marina Vincek (the name perhaps shortened to Minna) would then be his parents. It is perhaps too much of a leap of faith to believe that Fanny Modern née Pollak whose death in Budapest was mourned in 1885 was his sister, and that her given name corresponds to the middle name of their father, and that Marie Pollaky, the other mourner, was their elderly mother.

On my return from Bratislava, I continued online looking through the many records and scans of documents on the Family Research website of all the variations of the Pollaky name which might exist. I tried Polak, Polaki, Polaky, Pollak, Pollaki, Pollaky and several others. All had hits, sometimes the same family varied spelling between one record and another, but I still had to conclude that if what Pollaky said about his family is true, there are currently no records to be found which make an exact match. Looking at this second theory harder, I discovered that the Ignatius Polák baptised in 1819 had two older brothers, Josephus, baptised 1814, and Paulus, baptised 1817. This means that if Fanny Modern was their sister, and Marie Pollaky was their mother, the mother would have been quite old in 1885 when she was listed as a mourner. Moreover, I could find no trace of a daughter being born to that family. We must be careful; there were three other Ignatius Poláks, one born 1822 and the others in 1824, though none of them have parents with the correct names. (There is also an Ignatium Polaky born in 1783, and an Ignatius Polaki who became a father in 1794, both far too early to be of interest.) Third theory: he might still be connected to mother (Marie) and sister (Fanny) but not to the Polák family.

Breakthrough

And suddenly, without warning, came the breakthrough I had been looking for. The Toni and Gustav Stolper Collection 1866–1990 held by the Leo Baeck Institute, New York, a huge document, several hundred pages long, contains the following passage:

Translation from a MEMO written by Anna Jerusalem

The Family of Professor Dr. Max Kassowitz 1842–1913

The name of KASSOWITZ first appears in a register of Jewish families at Pressburg of 1736 …

The father of Max’s mother Katharina, nee Pollak, 1821–1878, named Ben Joseph Schames* and was caretaker of the Congregation. He was an intelligent, enlightened popular man whom his grandson Max lovingly remembered. When Max left Pressburg for the University of Vienna, his grandfather asked him to promise never to let himself be baptised.

A brother of Mother Katharina … Ignaz Polaky who compromised himself politically [aged] 19 1848, went as a fugitive to England, where he founded a Private Detective Agency; he acquired a high reputation with the Police, was knighted and awarded numerous distinctions; he was twice married to Christian Englishwomen, preserved great affection for his relatives on the Continent whom he frequently visited in later years.

There it was! Ignatius (Ignaz) Pollaky was the son of a Synagogue sexton and he had a sister called Katharina. So it seems that his family had lived on the (old) castle hill in Pressburg in the Jewish Quarter which no longer exists. As far as the rest of the paragraph goes, this book will show if the other statements are accurate in later chapters. Pollaky himself inflated his father’s importance in his declarations, but it is interesting to note the description of the elder Pollaky as intelligent, enlightened and popular. The original German as well as the English translation is included in the Stolper papers. Toni Stolper and Anna Jerusalem were both daughters of Max Kassowitz, and therefore Pollaky’s great nieces.

It seems likely that Pollaky had been involved in the dramatic events which took place in Hungary in the late 1840s, and that his activities had come to the attention of the authorities, causing him to try his luck elsewhere.

Hungary at that time had not been an independent country for many years. From the mid-sixteenth century, it had been variously divided between the Ottoman and Habsburg empires. By 1718, the Habsburg Empire had fully wrested control of it for themselves.

The Habsburgs, with their capital in Vienna, spoke German, hence the common use at the time of the German name Pressburg for Pollaky’s home city, rather than its Hungarian name, Pozsony. Like other countries and states ruled by Austria, Hungary was straining under the leash for independence.

On 15 March 1848 the Hungarian Revolution began. This was not the first time the Hungarians had fought for independence from Austria. From 1703 to 1711 Rákóczi Ferenc (Francis II Rákóczi) had led an unsuccessful struggle for Hungarian independence.

On 13 April 1848 the Hungarian Declaration of Independence was presented to the Hungarian National Assembly, and passed unanimously two days later. Naturally, the Austrian rulers were not going to accept this, and there were a number of insurrections throughout Hungary as a result. By July 1849 the revolution had been quashed by the Austrian army (with help from Russia). Hungary finally gained autonomy, though not full independence, from Austria in 1867.

There were anti-Jewish pogroms in Pressburg that took place in April 1848, and this also may have influenced Pollaky’s need to leave Hungary. There had been several losses of life. Some of the younger Jewish intellectuals were committed to the revolution, and after the pogroms, the Jews were ordered to leave Pressburg.

It seems clear that Pollaky had made his position there untenable, due to his support for the Hungarian revolution, and that he had fled. He made his way first to Italy.

At that time, the northern states of Italy were also trying to free themselves from Austrian rule. In early July 1849, Italian patriot Piero Cironi (1819–62), had been arrested by the Florence police for his involvement in these affairs, and on 12 July 1849 Cironi wrote of his imprisonment. The previous morning he had been joined by a young Hungarian from Pressburg, Ignaz Pollaky, who had been arrested in Livorno when on the point of embarking for Genoa. Cironi who wished for amicable conversation with a like-minded person, felt that it was unfortunate that Pollaky spoke Italian badly, but wrote that they had conversed in French instead.

Pollaky was not held for long – a few weeks later he arrived in England.

Note

* The word ‘Schames’ is not a surname; it means that Joseph was the caretaker or sexton.

2

Arrival in England

Pollaky arrived in London on 20 September 1849 on a day that was fresh and fine, with a west wind. The ship docked at Gravesend, Kent. The written records of entry on the relevant page in the records of Alien Arrivals in England are all in different hands, which implies that the individual passengers signed their own names there. His name is written as Pollaky Ignatz (Professor) – in Hungarian style the surname appears first.

There are, however, a number of conflicting records as to when Ignatius Pollaky first arrived in England. On 15 February 1846, a native of Austria called Pollacky (with the extra ‘c’) arrived in Dover from Ostend, Belgium on the Princess Alice. This individual then disappears from records. This is almost certainly not our man, unless he had made an earlier visit as a lone teenager to England. Pollaky was somewhat approximate when asked when he had arrived in England, whether because of faulty memory, or because he would write down whatever year was most convenient is hard to say.

On his application for British nationality made in 1914, he wrote that he arrived in 1851, whereas according to his earlier application for British nationality made in 1862, he arrived in 1852, although in a letter of 31 July 1862 to Sir Richard Mayne, Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, he writes, ‘during 12 years of residence in London & England I never was tried or convicted on a charge of felony or misdemeanour’. That would place his arrival in 1850.

Later, however, in the same letter he writes:

Mr Hodgson in the year 1858 wrote a letter to the Austrian Ambassador in London stating that during my residence in London (10 years) my conduct was always very good and that I during that period was instrumental to bring repeatedly Criminals (Foreigners) to justice (This letter is still on Record on the Books of the City Police.)

(Charles George Hodgson 1812–68 was Superintendent of the London City Police Force, the Austrian Ambassador at that time was Hungarian-born Count Rudolf Apponyi.)

Hodgson’s letter would place Pollaky’s residence in London from 1848. From it we can surmise that during the 1850s Pollaky was working at bringing foreign criminals to justice. However, that letter, if it was on record at the time, is certainly not available to examine now.

There is little information as to his activities or to his place of residence until some way into the 1850s. He does not seem to be recorded on the 1851 census, but that may only mean that he was out of the country at the time, and, given his itinerant way of life at that time, perhaps this should not be surprising. The census was not by any means foolproof, and an interesting example comes from 1851 in which one Hungarian resident (born 1829) of Bermondsey, London is listed as, ‘A Person refusing to give name’.

Pollaky evidently spoke, read and wrote a number of languages well. The best idea of his spoken English comes from an interview given in 1877, discussed in detail in Chapter 11. His characterful use of written English in his letters does include a few spelling mistakes, but what native writer does not suffer from occasional lapses? Examples of his characteristic use of English and his handwriting include: always using ‘th’ after numbers to indicate the date – 1th, 2th, 3th, 4th, 21th etc., frequently heading private letters, written in English, not Private & Confidential, but Private & Confidentielle, and almost always writing the letter ‘K’ as a capital letter – even in the middle of a word. As well as English and Hungarian, he is known to have spoken German, French, Spanish, and Italian, and he may have been familiar with Polish and Greek as well. On 7 January 1861 TheTimes reported that he acted as court interpreter for a Greek man, Staveis Kollaky (the similarity between surnames is a coincidence), who had been charged with stealing 180 yards of silk; on 23 March 1871 he acted as interpreter for one Liebitz Goldberg, who spoke Polish. (On both these occasions, Pollaky had been present on other business; his presence in the vicinity of the trials had been fortuitous.) It may be that he was able to interpret both Greek and Polish though perhaps these two gentlemen spoke other languages that he understood. We have already heard of Piero Cironi’s opinion of Pollaky’s Italian, others also would cast doubt on his language abilities, but his own self-confidence seems to have carried him through.

Something of the humbug, particularly in his early days when he was trying to make himself seem more important and effective as an investigator than he really was, as well as his being, perhaps, a bit of a busybody, combine in his letters with great energy. When he felt deeply about things, or became agitated, his handwriting became faster, stronger, less legible and had a greater number of errors. He does, however, manage to come over through his letters, as well as through newspaper reports about him as genuine and as having his heart in the right place – likeable, though sometimes extremely frustrated by the apparent resistance of officialdom to credit him with that genuineness. He tried very hard to ingratiate himself with Sir Richard Mayne (1796–1868), Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, but failed at every turn. From the coldness of Sir Richard’s responses to Pollaky, it is clear that he had very little patience with private investigators at the best of times. Both Sir Richard Mayne and Ignatius Pollaky are buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. (Pollaky in Plot 17308, Sq.68, Row 2.)

From the 1860s his newspaper advertisements and several letters he wrote included statements that he specialised in intelligence on foreigners living in Britain. Later still he would recommend registration of all foreigners upon arrival in Britain, with the further recommendation that they should officially contact their countries of origin before applying for British nationality. The latter suggestion was not met with universal approval. (See Chapter 13.)

3

‘Inspector Bucket’, Lord Lytton, Lord Derby, Lord Palmerston, the Road House Murder and Whicher

One of the major figures in Pollaky’s life was Charles Frederick Field, whose father, John, may have been the publican of the ‘Earl of Howard’s Head’ in Chelsea. Field was probably born in 1803, the fourth of seven children to John and Margaret Field.

In 1829, when the Metropolitan Police Force was created, Charles Frederick Field joined as a sergeant. He was promoted to inspector in 1833, and after an active career became Chief of the Detective Division in 1846. The new police force was headed by joint commissioners Charles Rowan and Richard Mayne.

Five foot ten and inclined to be stout, Field married Jane Chambers in 1841. He is described on the marriage certificate as ‘Inspector of Police’ residing in Limehouse, East London. His father, John Field, was described somewhat laconically, as ‘dead’. Charles Field reputedly became the model for Inspector Bucket in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House which began serialisation in 1852. Dickens, in a letter to TheTimes on 18 September 1853, denied it. That we know a fair amount about this colourful character is, nevertheless, due in no short measure to his writings.

Dickens wrote about Field on a number of occasions. Firstly as Inspector Wield in his piece A Detective Police Party published in 1850, then, again as Wield, shortly after in Three Detective Anecdotes. Dickens himself, in a letter of 14 September 1850 to his colleague William Henry Wills, associated the cleverly disguised name, ‘Wield’ with Field. In 1851 he wrote another short piece entitled On Duty With Inspector Field. All these appeared in Household Words, Dickens’s own magazine.

In 1851 Dickens had engaged Field to provide security at a performance of a comedy by Lord Lytton, a friend of Dickens. The play, Not So Bad As We Seem, was to be performed by Dickens’s amateur theatrical company (with Dickens himself in the cast), and Lytton who had acrimoniously separated from his wife was afraid that she would interrupt the performance. Dickens and Field were on friendly terms; Dickens occasionally accompanied Field when the latter was on duty. More information about this appears in Chapter 12. Dickens wrote in a letter dated 18 April 1862 to his friend, author George Walter Thornbury (1828–1976), that Field had been a Bow Street Runner, but there is no evidence to support this.

In December 1852, Field retired from the police force and opened a Private Inquiry Bureau at 20 Devereux Court. This building, built in 1676, had previously been the Grecian Coffee House where patrons had included Oliver Goldsmith the novelist, and Sir Isaac Newton and other members of the Royal Society. In about 1842, the coffee house had ceased business, and the premises was divided into ‘chambers’. Known as Eldon Chambers, a number of professional people kept offices there.

After his departure from the police force, the press often continued to refer to Field in their reports as Inspector Field – a fact that got him into trouble as the police believed him to be giving the impression that he was still associated with them.

Field was by no means the first to advertise his services as a private investigator. As early as the days of Queen Anne, who reigned between 1702 and 1714, one John Bonner was reputed to have published the following:

This is to give notice that those who have sustained any loss at Sturbridge fair last, by Pick Pockets or Shop lifts: If they please to apply themselves to John Bonner in Shorts Gardens, they may receive information and assistance therein; also Ladies and others who lose their Watches at Churches, and other Assemblies, may be served by him as aforesaid, to his utmost power, if desired by the right Owner, he being paid for his Labour and Expences [sic]. (Social Life in the Reign of Queen Anne by John Ashton, 1882.)

Reference to Bonner’s advertisement can also be found in Anecdotes of the Manners and Customs of London During the Eighteenth Century by James Peller Malcolm (1810), where it is explained in different terms: ‘John Bonner of Short’s Gardens had the bare-faced effrontery, in 1703, to offer his assistance, by necromancy, to those who had lost any thing at Sturbridge Fair, at Churches or other assemblies, “he being paid for his labour and expenses”.’ This kind of criticism, justified or not, would mark the attitude of many towards private investigators. Pollaky in particular suffered owing to that aura of exotic mysteriousness which hung around him, arousing suspicion and dislike.

One-time Bow Street Runner and first Chief Constable of Northampton, Henry Goddard, had been known to accept work in a private capacity possibly as early as the 1830s, and continued to do so until the mid-1860s. Much of Goddard’s private work came from the Forrester brothers, John and Daniel, who ran a detective agency from within the Mansion House building. They had been employed by the City of London Corporation, John Forrester from 1817, and Daniel from 1821, but they were not connected with the City of London Police which was formed in 1832.

In 1862 one of Pollaky’s early advertisements for his new inquiry office appeared in The Times directly above one placed jointly by the Forrester brothers and Goddard. The Forresters were by that time no longer at the Mansion House. Was it purely coincidence that Pollaky’s first business address was so close to that recently vacated by them? They were the most successful and the best known private investigators of their time. Had Pollaky hoped that some of their success might come his way if he used an address associated with them?

The Times – Wednesday, 7 May 1862

A VIS aus ETRANGERS. – Les feuilles publiques ont à plusieurs reprises signalé l’existence à Londres d’associations d’escrocs, dont le but special parait être de victimes le commerce et l’industrie. – Bureau de Renseignements, Mr Pollaky, P.G. [sic] Inquiry-office, 14 George-street, Mansion-house.

INQUIRIES. – Messrs. FORRESTER and GODDARD, late principal officers at the Mansion-house, city of London and the public office, Bow-street, undertake important and CONFIDENTIAL INQUIRIES for the nobility, gentry, solicitors, bankers, insurance companies and others in England or abroad. Offices No. 8 Dane’s-inn. Strand.

Pollaky often advertised in languages other than English. A loose translation of the above is: ‘Warning to Foreigners. – Public papers have repeatedly reported the existence in London of associations of crooks, whose particular purpose seems to be victims of trade and industry. – Intelligence Bureau, Mr Pollaky, P.G. Inquiry-office, 14 George-street, Mansion-house.

Pollaky’s Work for Field

It may have been from as early as 1853 that Ignatius Paul Pollaky began working for Field’s Inquiry Bureau. He continued to do so until 1861. Though it is impossible to be precise as to when his employment there began, by looking at the advertisements which Field placed in The Times, it is possible to see a progression, which taken in conjunction with various news reports allows glimpses into Pollaky’s development. During that time it seems that he worked on his own behalf as well.

Little trace of Pollaky’s early activities in England have been found, and that only from what he himself later wrote. What though, might one make of the following anonymous advertisement from 1852? Just the sort of skills he might have advertised at that time, though there is no way of finding the identity of the individual who actually placed it.

The Times – 1 April 1852

A Continental POLYGLOT PROFESSOR, translator and interpreter of 10 modern languages – English, French, German, Dutch, Spanish, Italian, Swedish, Danish, Portuguese, and Russian – celebrated by his divers polyglotic publications, recently settled in London, is desirous of obtaining PUPILS to teach, documents and books to translate, new works to arrange, counting-houses and schools to attend, private classes to form, a permanent situation; or a partner, able to advance £500 cash, to set up a general translating, interpreting, and consulting office for all nations. […] At 36 Northumberland-street, Charing-cross.

Field had a number of assistants, they are rarely identified by name. The following is typical:

Hull Packet and East Riding Times – Friday, 30 June 1854

CAPTURE OF A RUNAWAY BANKRUPT […] Mr. Inspector Field […] forthwith despatched his assistant to America.

In 1856 Field’s advertisements might offer rewards for lost items: £200 for a missing parcel, lost on a journey between Calais and Dover, containing precious stones, £25 for a lady’s dressing case left in a railway carriage – both advertised on 18 December – ‘Information to be given to Mr C.F. Field, late Chief Inspector of the Detective Police of the Metropolis, Eldon-chambers, Devereux-court, Temple’, the first of these proudly declared. On 25 March the following year he advertised to, ‘RENDER his SERVICES to any candidate at the forthcoming elections’. He sometimes advertised that he had agents in America, and that he would send a specially appointed officer to the continent on the first day of each month.

But from 2 March 1859, a change can be seen in both style and form. That day he placed two advertisements in The Times one above the other. The second was fairly standard fare; the first was in French. There can be little doubt that it was written by Pollaky. He was, after all, the language expert there.

The Times – Wednesday 2 March 1859

BUREAU de RENSEIGNEMENTS PARTICULIERS. – Affaires Continentales. – Le public est informé qu’un agent spécial de cet établissement partira de Londres pour le continent le 1er de chaque mois […]

Pollaky’s name soon began to be placed before the public in newspaper reports, though not yet in advertisements. The following is one of the earliest examples.

Falkirk Herald – Thursday, 2 February 1860

THE MISSING MR GEORGES HIRSCH

During these last 14 days, information has been received in London from Paris that a Mr Georges Hirsch who had lately come from South America, had mysteriously disappeared, and a reward of £100 has been offered for intelligence as to his whereabouts. The opinion on the Continent was that he had been murdered in England, or that another Waterloo Bridge tragedy had been enacted. The case was placed in the hands of Mr Polaky [sic], the foreign superintendent of Field’s Private Inquiry Office, who, from his inquiries set at rest the idea that Mr Hirsch has been foully used. It appears that, on the 31st of July, 1859, Mr Hirsch wrote a letter to Messrs Rimmel, the eminent perfumers of 96 Strand, purporting to be signed by Marchand and Mathey, of Rio Janeiro, intimating that the house could dispose of a large quantity of Messrs Rimmel’s various goods; that, on or about the 12th day of December last, Mr Hirsch called on Messrs Rimmel, and selected perfumery to the amount of £240; and that, after he had so selected the goods, he prevailed on the above gentlemen to discount £700 value in bills which Hirsch had brought with him; that, on or about the 14th December, Hirsch proceeded to different parts of the country, adopting the English name of Stevens, and taking with him various small Bank of England notes, having previously changed the large ones – amounting to £550, and endorsed them in his new name. Mr Pollaky traced Hirsch to several towns in England where he had been purchasing goods, and to the hotels where he had been living in London and Liverpool under his assumed name. What could have induced Mr Georges Hirsch to have acted in the manner described will no doubt have hereafter to be explained. It is almost needless to say Mr Hirsch never paid Mr Rimmel for the goods, nor did he return to this gentleman after he had obtained discount of the bills. The Home Office was set to work to cause inquiries to be made about the missing Mr Hirsch but a telegraphic message from Mr Field to Paris soon put out of the question further trouble on the part of the Government.

Two weeks later, Pollaky’s name was again mentioned in a newspaper report. Five of the crew of the ship John Sugars were charged with conspiracy to injure the captain, and to charge him with the loss of the ship. Three of them were eventually found guilty, and sentenced to imprisonment.

Morning Chronicle – Friday, 17 February 1860

THE ALLEGED WILFUL SINKING OF A MERCHANT SHIP

Yesterday morning the inquiry instituted by the Board of Trade for the purpose of investigating the circumstances connected with the wilful sinking of the barque John Sugars was resumed at the Greenwich Police-court before Mr Traill the presiding magistrate.

Mr Cumberland attended for the Board of Trade, and Mr Digby Seymour, MP, for the defence. Mr Ignatius Pollaky, from the Mansion-house, acted as interpreter; and Mr Henderson, from Lloyd’s Shipping Insurance-office was present to watch the proceedings.

The mention of Pollaky being from the ‘Mansion-house’ is something of a puzzle, although in October 1861 he wrote a letter to Henry Sanford on Mansion House-headed writing paper. He would over a year later, open his own office in George Street, Mansion House (now Mansion House Place). The following report gives him his usual title, though it does misspell the name of the ship.

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper – Friday, 11 March 1860

THE RECENT ALLEGED WILFUL SINKING OF A SHIP AT SEA

The extraordinary contradictory evidence set forth in the official inquiry at the Greenwich police-court, respecting the alleged wilful scuttling and abandoning of the barque John Lugars [sic] (Captain Hewett), has led the owners of that vessel to indict five of the crew (upon whose statement the inquiry was instituted by the Board of Trade) for perjury and conspiracy. Four out of the five being Prussians, Mr Pollaky, superintendent of the foreign department of the Private Inquiry Office, Devereux-court, Temple, having interpreted the evidence during the inquiry, was retained for the identification of the men; and a true bill having been returned by the grand jury at the past Old Bailey sessions, a warrant, signed by Mr Gurney and Alderman Hale, was placed in the hands of Inspector Hamilton and Sergeant Webb, of the city detective force, and they, in company with Mr Pollaky, went in search of the men, and succeeded eventually in arresting them in Ratcliffe highway.

Further information about Pollaky can be found in the Old Bailey trial transcript. The initial inquiry had taken place in Greenwich before Police Magistrate James Traill. Pollaky had acted as interpreter for the German-speaking crew members. When he then appeared as a witness at the trial at the Old Bailey in May 1860, after firstly stating that he had acted as interpreter and that he had, ‘interpreted well and truly’, he was then briefly cross-examined by Mr Sergeant Ballentine who was acting for the defence, and then by Mr Digby Seymour who was now acting for the prosecution.

Mr Sergeant Ballentine: What else are you besides an interpreter?

Pollaky: I am superintendent of a private inquiry-office in the Temple – I am not a servant of Mr Field’s; I am in connexion with him – I have never been engaged as interpreter in any nautical inquiry before – I am not connected with nautical matters.

Mr Seymour: Were you employed by the Board of Trade?

Pollaky: Yes; I saw another interpreter there to check me.

From which can be seen that Pollaky was fully entitled to act independently from Field.

The advertisements in The Times evolved during the period 1859 to 1861, and on 21 May 1860, Field’s office placed one which included the phrase, ‘The foreign Superintendent of this establishment will this week proceed to Paris, Belgium, and Germany’. It is surely only a small step to the view that he had often been the agent sent on European missions. The advertisement placed on 30 June 1860 offers the information that, ‘The foreign superintendent, who is conversant with the French, German, Italian, Spanish, Turkish, and other languages, is in daily attendance, between the hours of 2 and 4 p.m.’ – information not only on Pollaky’s working hours, but also of his amazing facility with languages, mentioning Turkish among his polyglot skills. Pollaky’s importance to the company was evidently growing, and that passage now appeared regularly, but his name was not yet mentioned in the advertisements. And then the following advertisement appeared:

The Times – Thursday, 6 September 1860

IF Mr MORITZ FRIED, late of Vienna, will be good enough to CALL on Mr Pollaky, 20 Devereux-court, Temple, he will HEAR of SOMETHING to his ADVANTAGE.

And Pollaky’s name suddenly springs up in one of Field’s advertisements.

Finally, Field must have allowed his name to be mentioned, like a reporter being given a by-line for the first time, and he is credited as an important member of the team. In the future advertisements would read not, ‘The foreign superintendent is in attendance between the hours of 2 and 4 p.m.’ but ‘Ignatius Pollaky, superintendent Foreign Department, in attendance between the hours of 2 and 4 p.m.’. Pollaky’s presence must have been deemed enough of an asset to Field’s company to make it worthwhile for his name to be featured in this way. Probably Pollaky himself had a hand in ensuring that his name was given this prominence, he was, after all, a pushy young fellow with high ambitions.

The Road House Murder

In 1860 the infamous Road House murder took place. This is described (with a small mention of Pollaky) in Kate Summerscale’s book The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. In 1861, a year after the murder, J.W. Stapleton published a book called The Great Crime of 1860, in which he also discussed the matter in some detail. There are a number of references in Appendix IV of that book to Pollaky being present at one of the official examinations into the case in November 1860, although the reason for his presence mystified everyone. It is noted that the ‘proceedings were being closely watched by Mr Pollaky, who appeared to take notes of any expressions made by Mr. Saunders’ (the examining magistrate).

Jonathan Whicher, the police inspector in charge of the investigation, joined the Metropolitan Police Force as a police constable in 1840 and became an inspector in 1856. Charles Dickens, writing his story Detective Police, the same piece in which he disguises Field’s name as Wield, described Whicher, then a sergeant, ‘Sergeant Witchem, shorter and thicker-set and marked with small-pox, has something of a reserved and thoughtful air, as if he were engaged in deep arithmetical calculations.’ It is possible that Dickens’s friend and occasional collaborator Wilkie Collins based the character Sergeant Cuff in his 1868 novel The Moonstone on Whicher, who in 1893 would be described as, ‘the Prince of Detectives’ by ex-Chief Inspector Timothy Cavenagh in his memoirs. (The same phrase would be used to describe Pollaky a few years later.) Whicher must have resented Pollaky’s presence hanging over his investigation, and he figures again in Pollaky’s story in a not too favourable light. Later in The Great Crime of 1860: ‘Mr. Saunders did not meet Mr Pollaky at Bath, but they were seen in conversation on the Bradford railway station on Saturday.’ And again: ‘The mysterious Mr Pollaky was there, and took notes of several parts of the proceedings.’

The Times had reported on Pollaky’s presence at the time, and its reporter was as puzzled by it then as Stapleton was when he wrote his book, stating on 9 November that, ‘Among the persons present to-day the reporter recognised Mr J. Pollaky, […] but the nature of his visit did not transpire.’ On 12 November, the reporter hazarded a guess about Pollaky’s mission, stating that it was, ‘believed to have no reference to the tracing the murderer [sic], but rather to collect information in reference to the extraordinary proceedings which have taken place during the past week’, – a statement which really leaves us very little the wiser.

The fact of Pollaky’s presence, and he was already well known enough to be featured in Stapleton’s book, puzzled many, and must have annoyed not a few. It would certainly not have been pleasant to Inspector Whicher, who was having enough problems trying to solve this infamous case (while at the same time dealing with the demands of public, press, and Sir Richard Mayne), without having the interfering presence of this mysterious Hungarian watching the proceedings. Pollaky must have been there for a reason, but that reason remains a mystery.

Pollaky’s name continued to appear:

The Times – Thursday, 3 January 1861

C. – Milan. – The documents have been returned to the Federal authorities, as I understood from his Excellency, by mutual consent, in June last, the MATTER is, therefore, de facto SETTLED. – POLLAKY. Superintendent, Private Inquiry-office, No. 20, Devereux-court, Temple, 2d January, 1861.

On 6 October 1860 Field had advertised in The Times for information regarding a certain Ernest Brown who had embezzled various sums of money. Ernest Brown or Brewer, the name varies depending on which report one reads, tried very hard to evade capture, but, as the following item shows, had a hard time of it. Field assigned Pollaky to the case.

The following news item was published in Australia but had previously appeared in a number of English newspapers in one form or another. An exciting case of tracking down and following a criminal, it shows a tenacious Pollaky at work in late 1860 and early 1861. The report is quoted in full. Sergeant Spittle, who also appears later in this book, takes the role that would be assumed twelve years later by Inspector Fix in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days:

Sydney Morning Herald – Friday, 10 May 1861

THE DETECTIVE SYSTEM

The detective police have, within the last few days, obtained a clue likely to lead to the apprehension of a criminal who, in September last, absconded from his employer’s service, after having embezzled over £10,000, a considerable portion of which he is believed to have had in his possession at the time he left this country. The person referred to was a man named Ernest Brewer [Brown], who had been for twenty years in the service of a firm of foreign merchants, carrying on business in Throgmorton-street, and in whom the greatest confidence was reposed. It would seem that he took advantage of his position, and, by falsifying the books and other means, obtained possession of a very large sum of money.

He absconded about the 20th of September, at which time one of the principals of the firm was on the Continent; but he was expected home, and the culprit, possibly anticipating that a discovery would take place, resolved upon flight, having previously taken the most extraordinary precautions to prevent being detected.