Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'The best biography I've read recently' – Colin Bateman, Sunday Independent 'An excellent examination of Mayne… Ross corrects many of the myths about him that have flourished over the years' - History of War magazine 'This welcome reassessment, officially backed and well-researched, sets the record straight' – Soldier magazine 'Paddy' Mayne was one of the most outstanding special forces leaders of the Second World War. Hamish Ross's authoritative study follows Mayne from solicitor and rugby international to troop commander in the Commandos and then the SAS, whose leader he later became and whose annals he graced, winning the DSO and three bars, the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d'Honneur. Mayne's achievements attracted attention, and after his early death legends emerged, based largely on anecdote and assertion. Hamish Ross's closely researched biography challenges much of the received version, using contemporary sources, the official war diaries, the chronicle of 1 SAS, Mayne's papers and diaries, and a number of extended interviews with key contemporaries. Ross's analysis shows Mayne to be a dynamic, yet principled and thoughtful man, committed to the unit's original concepts. He was far from flawless, but his leadership and tactical brilliance in the field secured the reputation of the SAS, proving he was every bit a rogue hero.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 556

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

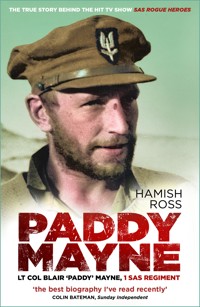

Front cover image: Blair Mayne in the desert. (Imperial War Museum)

First published 2003 by Sutton Publishing Limited

First published in paperback 2004

This paperback edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Hamish Ross, 2003, 2004, 2023

The right of Hamish Ross to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75246 965 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by Mike Sadler, MC, MM, 1 SAS

Preface by Fiona Ferguson, niece of Lt Col Mayne

Acknowledgements

Part I

1 The Legend

2 Ireland 1915–1940

Part II

3 11th (Scottish) Commando

4 The Desert Raiders

5 Special Raiding Squadron

6 Fair Wind for France

7 Later Operations

Part III

8 Antarctic Interlude

9 My Usual Quiet Life

Part IV

10 Ashes of Soldiers

11 Growth of a Unit

Afterword

Glossary

Notes

Bibliography

About the Author

FOREWORD

Mike Sadler, MC, MM, 1 SAS Regiment

It is good to be able to welcome a new assessment of Blair Mayne – Paddy, to all who knew him in the wartime SAS. There were certainly a number of fellow Irishmen in the regiment at that time, but there was never any doubt as to whom one meant when referring to Paddy. Good also to see a new appraisal at the present juncture when the band of those who got to know him in the war is rapidly diminishing. Furthermore, through his meticulous research the author has turned up much new information, which has become available since the last time anything was published about Paddy and contributes to casting new light upon his outstanding abilities as an unorthodox soldier and on his unusual personality.

Although much has been written in the past about Paddy’s exploits, some of it has seemed misleading and even rather derogatory. This has been due, in part, to its having been based on hearsay long after the event, and sometimes to the writers’ inclination to exaggerate a situation for dramatic effect. The present author’s researches should go far to provide a more balanced picture of a most remarkable man, and should provide rewarding study for anyone interested in the past history of irregular warfare.

I was fortunate to see quite a lot of Paddy, both in operational and social situations during the war. I first met him in the dusty desert outside Jalo, behind enemy lines in Libya. I was navigator in the LRDG patrol which was to take him and his small SAS team to the vicinity of an enemy airfield at Wadi Tamet, some 350 miles yet further to the west, where he would carry out the first successful raid of the many he was to undertake against enemy airfields. Thereafter, having myself transferred to the SAS, I saw much of him in the desert, accompanied him when he parachuted into occupied France, celebrated with him in Paris (perhaps rather too liberally) following its relief, joined him on visits to his home in Ireland, and saw something of him in the Antarctic on his unfortunately curtailed visit to the south at the end of the war.

From the earliest days, it was obvious to all that Paddy was a brilliant and determined operator in the field. What was less obvious – at least to the rank and file such as myself – until the capture of David Stirling led to Paddy’s elevation to command of the regiment, was that he had also developed a considerable talent for the arts of leadership, planning and staff work. The extent to which this has been revealed in the course of the author’s researches has been of particular interest to me and no doubt to all who have followed the many and varied interpretations of Paddy’s career and character. However, his abilities as an administrator notwithstanding, there is no doubt that he could hardly wait to get back to operations in the field, which is where his greatest talents lay.

Although he was a very complex character, and could certainly be unpredictable at times, he was a great person to be with in almost any circumstances. A quiet man who hardly ever raised his voice, he got the results he wanted by his large (in every way) presence and by example. Everyone was very much aware that he would never expect anyone to do anything, or to take any risk, that he was not prepared to undertake himself; and this certainly contributed to his success as an outstanding leader of soldiers in the field of unconventional warfare.

PREFACE

Fiona Ferguson, niece of Lt Col Mayne

Hamish first approached me two and a half years ago with the idea of writing an article about my uncle Blair. I was at first very hesitant – was this going to be a rehash of the old stories, only even more embellished? Even as a young girl I was aware that ‘everybody’ knew Blair personally, and, once my relationship was known, I would have to listen to an even better version of a story I had heard many times before. The pubs in Newtownards must have made a fortune from the number of people in them when Blair was there who had witnessed these deeds in person. I also didn’t see how I could help. I was only ten when Blair died – my father had given the war diary to the SAS and all I had were the scrapbooks of newspaper cuttings kept by my Aunt Barbara, letters and other documents kept by various members of the family, especially my father and Aunt Francie, plus some of Blair’s own papers.

However, Hamish had been given my name and address by Jimmy Storie, whom I had met at the unveiling of the statue of Blair in Newtownards and on a couple of occasions since with his lovely wife Morag. If Jimmy was prepared to talk to Hamish it would be churlish of me to refuse to help in any way I could. What I hadn’t realised was that among Francie’s papers, which came to me on her death, was a diary that Blair had kept in the Antarctic. Soon after he had read this I realised that Hamish was determined to get to the true man and was doing his utmost to talk to the few remaining people who really knew Blair – not those acquaintances who claimed friendship so as to bask in the reflected glory.

I knew my father would not react kindly to the idea of a new book, so I did not tell him until I was convinced that Hamish was after the truth – warts and all. Dad has now read the manuscript and is very impressed with the research Hamish has undertaken. No previous author has attempted to do anything similar – they have just reiterated the stories of armchair friends.

If anyone were to ask me which book they should read about ‘Col Paddy’, my unreserved answer would be, ‘the one by Hamish Ross’.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

What began as an idea for a journal article on Blair Mayne’s transition from Special Services leader to legal administrator developed into this book thanks to the range of the papers that his family kept. So I am therefore most grateful to Fiona and Norman Ferguson for giving me access on different occasions to the Mayne family papers, specially to Fiona for her patience in responding to my many queries, and for writing a Preface.

I am particularly indebted to the Secretary of the Special Air Service Regimental Association for giving me access to what the Regimental Association refers to as ‘The Paddy Mayne Diary’, as well as to other files, and for enabling me to contact former members of 1 SAS Regiment. I should like to thank those contemporaries of Blair Mayne, who not only gave their time to my questions, but reviewed the written transcripts of their interviews, and, in many instances, over a prolonged period, were prepared to re-engage in discussion in the light of further documentation which emerged. I especially want to thank Mike Sadler for the input he gave over almost two years and for writing the Foreword to the book.

For permission to use copyright material I should like to thank Margery Badger, Anne Holmes, George Franks, Elizabeth Humphryes, James O’Kane, Registrar Queen’s University Belfast, Stewarts Solicitors, Newtownards, Eoin McGonigal, Senior Counsel, Dublin, Professor Graham Lappin, Martin Vine, Archivist, British Antarctic Survey, Lady Jean Fforde and Sir Thomas Macpherson.

Lines from ‘Under Ben Bulben’ by W.B. Yeats are taken from the Everyman’s Library anthology, Yeats Poems, 1995, and are reprinted by kind permission of the publisher. The extract from Once There Was A War by John Steinbeck, Penguin, 1977, © John Steinbeck, is reprinted by kind permission of the publisher. The stanza from Sorley MacLean’s ‘Going Westwards’ appears in From Wood to Ridge, 1999, published by Carcanet Press and is reprinted by kind permission of the publisher. The extract from The Naked and The Dead by Norman Mailer is reprinted by kind permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, © Norman Mailer, 1949. Lines from ‘Digging’ from Death of A Naturalist by Seamus Heaney are taken from the anthology Opened Ground: Poems 1966–1996, 1998, and are reprinted by kind permission of the publisher, Faber & Faber Ltd.

I am grateful to a number of people for specific help. From the University of Glasgow, Bill Buckingham, Department of Modern History, Mike Shand, Department of Cartography, Cathair O’Dochartaigh, Department of Celtic, Willie McKechnie, Photographic Unit and James Steel, Department of French. I would like to thank Mark Creamer, Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, University of Melbourne, Karen Robson, Senior Archivist, University of Southampton, staff at the Public Records Office, the staff of Whiteinch Library, Ian (Tanky) Smith, Jimmy Lappin, Ewan Ross, John Lewes, Eric Taylor, Heather Semple, Head of Library and Information Services, The Law Society of Northern Ireland, William Cumming, solicitor, Terence Nelson, Royal Ulster Rifles Association Museum and Clifford Manley, Vice Principal Regent House Grammar School.

I want to thank Stewart McClean of the Blair Mayne Association for his help and unfailing courtesy; and I would like to make particular mention of the excellent help of David Buxton. Walter Marshall, who has done so much to perpetuate a record to No. 11 Commando, has been most supportive, and Eileen Mander and Archivist Stuart Gough of the Isle of Arran Heritage Museum gave valuable assistance.

Finally, for meeting me when the book was nearing completion and for giving me his encouragement, I should like to thank Douglas Mayne.

PART I

1

THE LEGEND

Ransom Stoddard: You’re not going to use the story, Mr Scott?

Maxwell Scott: This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

from the film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, directed by John Ford

An Irish solicitor, Blair Mayne – or Paddy Mayne as he was more widely known – became one of the most outstanding soldiers and leaders of the Second World War. He had been an international rugby player, who represented Ireland and played for the British Lions before the war; and after serving in a Commando and seeing action in Syria, he joined the new unit that David Stirling was establishing – the Special Air Service. The record of Mayne’s achievements in little over twelve months with the SAS in the North African Desert reads like fiction; yet it is factual and well recorded. The groups he led destroyed over one hundred enemy planes on the ground. These raids, with few exceptions, were carried out on foot and by stealth. Luck was an element in these successes, but the one common factor was Mayne’s ability to read the situation on the ground, anticipate how the enemy would react, and then attack. He was twenty-seven years of age when he won the DSO for the first time. Over the next three years, Mayne led the unit in Sicily and mainland Italy in a very different kind of warfare; then in France, behind enemy lines; and in Germany, where the unit was the spearhead of an armoured thrust. In each of these three campaigns, he added a further bar to the DSO, then received the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’Honneur. At the end of the war, after a short period with an Antarctic Survey, Mayne returned to the law, becoming a senior official in the Law Society of Northern Ireland. In 1955, he died in a car accident at the age of forty.

Heroic military figures have long been the subject of public interest, not only because of their achievements, but for what motivates them. There is fascination with the heroic contempt for personal safety that defies common experience; and there is something of an aura of mystery about the hero, which often gives rise to legend. In Mayne’s case, the newspapers began the trend during the war: he was compared to Bulldog Drummond,1 the fictional hero of spy thrillers of the twenties and thirties; and he was also described as a famous pre-war international sporting figure, coolly strolling into an enemy officers’ mess and attacking its occupants, before moving on to the next job; and by the time he was decorated by the king with the third bar to the DSO, they had increased his height by four inches to six feet six. Decades later, first a radio series and then a television programme about Mayne made their contribution with hyperbole.

At the end of the war, though, the first personal accounts began to emerge from those who had served in the SAS. A maxim that has long been established in combat units is that comrades know those who are truly worthy of recognition. Two of Mayne’s colleagues wrote of their time in the SAS: Malcolm James Pleydell,2 its first medical officer, and Fraser McLuskey,3 its first padre. Both men wrote insightfully of Mayne, what manner of man he was, and of the respect and regard in which he was held by his men.

But soon after his death, however, misinformation about Mayne began to appear, first of all in books about others. Keyes somewhat pejoratively attributed to him the authorship of an operational report of a troop’s actions at a Commando raid in Syria,4 which in fact had been written and signed by another officer.5 Two years later, Cowles erroneously claimed that Mayne’s progression from the Commando to the SAS came about when he was rescued after some weeks under close arrest for having punched his superior officer.6 In reality, Mayne had left the unit the previous month.7

The first book about Mayne was written by Patrick Marrinan8 and appeared two years after the claim by Cowles. Marrinan approached his material very much in the tradition of a Boy’s Own account. He had read Cowles’ account of the early SAS and cited from it; and he simply accepted the fanciful tale of how Mayne came to join the SAS, and went on to create a scenario for it. To be fair to Marrinan, at the time he would not have had access to the war diaries which would have given evidence to refute the claim. But, on the other hand, Mayne was his subject (since Marrinan had been a barrister, Mayne was also in a sense his client) and he had read his letters, which, if he had cross-checked with published accounts about No. 11 Commando, at least would have made him question the unfounded claim. Instead, he consolidated a legend: the future leader of the SAS was brought into the light from prison to be offered the opportunity to prove himself and become its greatest warrior. Throughout, Marrinan treated Mayne as a larger-than-life character, personally motivated, whose actions happened to coincide in general with the Allied war effort. It all very neatly fitted the tradition and style from which it was derived. But Marrinan was also nearly contemporary with his subject; and in writing about Mayne’s postwar life, he found that it was too dull to be of interest, for he devoted only ten pages to it. However, he left two references about Mayne which were to prove prescient. He wrote that during Mayne’s lifetime, exaggerated stories about him were widely circulating; and, secondly, he did his best, according to the way society perceived it at the time, to encapsulate Mayne’s state of mind after the war. And there things may well have remained.

However, twenty years later the SAS attack on the Iranian embassy was filmed by television cameras and the regiment became the subject of intense public interest. A generation after Marrinan’s book appeared, Bradford and Dillon wrote about Mayne.9 They too presented him in heroic mould, but they gave their subject a more modern treatment, portraying him as a flawed hero. Not only did they accept the received version of Mayne’s entry to the SAS – via a prison cell – but with them the tale reached its apotheosis; for they postulated that it might have occurred because he was not selected to take part in what became known as the Rommel Raid, and lashed out in anger. In truth, of course, by the time the idea of an attempt to kill or capture Rommel was discussed as an option for No. 11 Commando, Mayne had been out of the unit for three and a half months. Although their treatment was modern, it had overtones of the classical tragic hero of drama who is fatally flawed. Now even assuming a punch had been thrown at a senior officer (junior officers have punched their superiors in the past and will do so in the future), it is hardly an indication of a deep character flaw. But according to Bradford and Dillon’s account, the tendency recurred throughout Mayne’s career, the evidence for which came from anecdotal accounts collected over forty years after the events. Moreover, they portrayed him as something of a serial assailant. For example, they produced a new tale that was not in circulation in Marrinan’s time, the events of which were supposed to have occurred at the end of the desert war. The plausibility of these tales is heightened by their association with a well-known figure – the son of the Director of Combined Operations, or the well-known broadcaster, Richard Dimbleby – but this is also where they fall apart, when dates and movements are analysed. Nonetheless, Bradford and Dillon’s interpretation of Mayne passed into the canon of books about the desert war and the SAS Regiment.

No research into Mayne himself had ever been carried out. And what has characterised references to him in more recent writing has been an uncritical acceptance of a fiction about how he came to join the SAS; and the transference of assumed underlying anger and aggression to the battlefield – with connotations of a latter-day Viking berserker – to account for his heroism. But Stirling did not invite Mayne to join the unit expecting an undisciplined killer: he had been told about Mayne’s leadership of his troop and his tactical skills during a Commando operation at the Litani river. And right from the beginning of the SAS, there was a philosophy concerning the qualities they looked for:

An undisciplined TOUGH is no good, however tough he may be. Most of ‘L’ Detachment’s work is night work and all of it demands courage, fitness and determination of the highest degree and also, and just as important, discipline, skill and intelligence and training.10

One of the earliest written assessments of Mayne by an insider included the quality of Mayne’s judgement and his firm conviction that ‘to take unreasonable risks was to invite disaster’. The SAS Regimental Association obituary of him stated that ‘In spite of his great physical strength, he was no “strong-arm” man.’11 Then, from the evidence of actions for which he was decorated, the personal capabilities which made him so successful were not blind fury or brute strength, but insightfulness, coolness of execution and the willingness to expose himself. Mayne’s first DSO was won in stealth raids, where he achieved the destruction of a great amount of enemy equipment, fuel and bomb dumps – strategic targets – hitting Rommel’s capabilities very heavily; in the early phase of the unit’s operation direct contact with enemy troops was usually avoided, although some specific attacks were made on them. Then one bar to Mayne’s DSO was received for a coolly conceived and brilliantly executed raid on a coastal battery, followed the next day by the audacious first daylight amphibious raid in the European theatre. The third bar to his DSO (his superior officers signed a citation for the VC) was for an action in which Mayne, by then the Colonel of 1st SAS Regiment, drove his Jeep under heavy and sustained enemy fire, while one of his officers manned its machine-gun, to rescue some of his men, who were wounded and pinned down.

There was also a strong oral tradition which developed around the SAS desert raids. One of the most frequently cited stories concerned an attack on a building containing enemy troops that Mayne carried out during his first successful raid on an airfield. Over the decades, however, the storytelling tradition became corrupted to such an extent that when it appeared in the official biography of David Stirling,12 it was in the form of a vivid eyewitness account by someone who did not even take part in the raid (but who was with Mayne two weeks later when he raided the same airfield again).13 Indeed, this particular operation turns out to be almost a case study of the way Mayne’s reputation has become dramatised and isolated. Reporting of Mayne’s action that night first emerged, fashioned by the wartime press,14 as a description of nonchalant blood-spilling at close quarters; it diversified through frequent retelling, with versions appearing in numerous accounts of the Special Services; then it became part of late postwar reassessment, with airbrushing here and there; and sixty-one years after the event, it resurfaced in the correspondence columns of a newspaper as item number one in a litany of infamy about Mayne.15 But, as we shall see, the record shows that Mayne’s actions were neither different in kind nor distinguishable morally from those of several of his contemporaries; they were but one element in a wider strategy – an element that had, even before the SAS was formed, the approbation of the scholarly General Wavell.

The zenith of the legendary Mayne is associated with the desert war. Thereafter, interpretation of him tends to fall into stereotypical attributes and characteristics. For example, such a first-rate exponent of irregular warfare, who, it was asserted, had a matching rebellious disposition, would not ordinarily be expected to conform to authority. True to pattern, claims were made that he was resentful and contemptuous of higher command. So it is somewhat surprising to read that, in September 1944 after the BBC broadcast news of General Montgomery’s elevation to field marshal, Mayne had a message of congratulations transmitted from his base in occupied France to be passed to the field marshal.16 Even more surprisingly, the following year, in north-west Germany, when the unit was not being used to best advantage and Mayne was making representations about the integrity of the SAS role, his brigadier signalled to him to be assertive in dealing with higher authority.17

That the dominant interpretations of Mayne have been built up from second-hand account, anecdote and assertion is quite astonishing. It is also a matter of some concern that historical accuracy has been abandoned for versions of events, built round a number of accounts, which, as we shall see, in many cases are refuted by the contemporary documentation. Above all, that these have concentrated on placing him somewhere between a superman and a dissident in an elite unit means that there has been no proper consideration of the impact Mayne made on the continuation and development of the SAS. For after Stirling’s capture – less than eighteen months after he had founded it – in no sense could it have been assumed that, like an established battalion, the unit had an ongoing existence that superseded any individual leader. There was pressure that it should be disbanded or absorbed into the Commandos, because its usefulness had been confined to desert warfare. Mayne resisted that, but he had to compromise to some extent until he had opportunity to prove the unit’s calibre in Sicily and mainland Italy. Mayne’s understanding of what had to be done in the changed circumstances, before the unit’s original concepts were re-established for its role in France, is clearly discernible. All of which means that over the decades Mayne the leader has remained inscrutable.

Fortunately, a large amount of contemporary evidence exists; so it is possible to get much closer to the man than at first might have seemed likely. Trained as a lawyer, Mayne kept good records. In No. 11 Commando, he was schooled by Lt Col Pedder, who was meticulous about report writing (Mayne’s report of the first SAS raid on the Gazala and Timimi airfields reflects the style). In 1943, when he took command of the unit, he opened a personal file in which he kept correspondence from contemporaries and drafts of letters he sent. His family, too, kept his papers; his most vivid letters, containing detail of the desert raids, were written to his younger brother Douglas; and his sister Barbara compiled a scrapbook of wartime newspaper cuttings about him and the unit. Then, most recently, on the death of his sister Frances, Mayne’s own journal, which he kept immediately after the war, was discovered. Frances had been a teacher who had risen to a high level in the ATS during the war and then returned to teaching. On Mayne’s death, all his papers passed to Douglas, but Frances must have read her brother’s journal and kept it as a memory of him, for Douglas knew nothing of its existence until 2002. It is a remarkable journal, written with candour, expressing Mayne’s feelings about others, reflecting on himself, and giving insights into his own personality. But it also reveals the extent to which he was thoughtful about leadership; and when considered alongside some of his wartime reports and analyses, it certainly enhances an understanding of the man.

At the level of official documentation, detailed war diaries exist for No. 11 Commando, although little seems to have survived from the early period of the SAS – particularly the unit’s activities in the North African desert.18 But there is a valuable source, now known as the ‘Paddy Mayne Diary’, which belongs to the SAS Regimental Association. It is not really a diary, more a chronicle of the unit, entitled ‘Birth, Growth and Maturity of 1st SAS Regiment’. The document was compiled in the summer of 1945 by Mike Blackman, Intelligence Officer with the unit at the time, and was presented to Mayne. It contains the names of the original members of L Detachment, structured in two troops: No. 1 Troop, commanded by Jock Lewes, and No. 2 Troop, commanded by Mayne. There is an editorial introduction describing David Stirling’s founding of the regiment and a brief overview of it, followed by an encomium to Mayne and to the way he led the unit. It is a compilation of the reports of many of the desert raids that Mayne undertook; as such it was selectively put together. It contains some press cuttings and details of personnel who would have been of particular interest to Mayne; it has reports that are copies of documents from war diaries held in The National Archives (occasionally Blackman used editorial discretion, making a phrase read more felicitously than the official record), in themselves quite valuable, particularly in view of the lack of war diaries covering the desert raids. After his death the ‘Diary’ passed to Mayne’s brother Douglas. Douglas gave access to it to Cowles (who described it as a scrapbook assembled by Mayne),19 to Marrinan (who did not refer to it but made use of it) and to Bradford and Dillon (who claimed that it had been appropriated by Mayne).20 Later, Douglas donated it to the SAS Regimental Association. Then there are, from 1943 onwards, the war diaries of the unit and the reports and evaluations Mayne himself wrote. Contemporary documentation can be illuminated by personal accounts, and this work is informed by written transcripts of extended interviews with a number of people who knew Mayne. These transcripts then became the basis of further dialogue with the respondents, and were cross-referred to contemporary documentation.

Stripping away the legend leaves Mayne not diminished but enhanced. He emerges as a reflective man; a man of mental strength, moral integrity and sensitivity; a very modest man, who was complex, who had some local neuroses, which in the later stages of his life were overlaid to some extent by his war experiences. Mayne’s leadership and his contribution to the SAS Regiment will speak for themselves.

2

IRELAND 1915–1940

Many times man lives and dies

Between his two eternities,

That of race and that of soul,

And ancient Ireland knew it all.

Whether man dies in his bed,

Or the rifle knocks him dead,

A brief parting from those dear

Is the worst man has to fear.

W.B. Yeats, ‘Under Ben Bulben’

Robert Blair Mayne was born in Newtownards, County Down, Ireland on 11 January 1915. He came from a family that had been associated with business and the law for three generations. His great-grandfather William Mayne was a prominent businessman and property owner in Newtownards early in the nineteenth century, and a Justice of the Peace at a time when that office was regarded as having considerable honour. His grandfather Thomas Mayne was widely respected in the community for his upright character; and his father William Mayne continued the family tradition, owning property and running a retail business in the town.

Blair, as he was to be known, was the second youngest of a family of four brothers and three sisters. He was named Robert Blair after his mother’s cousin, who at that time was serving as an officer in the trenches in France. The First World War that was to end all wars had been prosecuted for less than six months; the Easter Rising was a year into the future; and Ireland was not yet partitioned.

When he was four years old, his younger brother Douglas was born. When he was ten, his oldest sister Molly got married and moved to Belfast. The two remaining sisters, Barbara and Frances, got on well with their four brothers – Tom was the oldest, Billy was younger than Barbara – but they had a very warm big-sister relationship with the two younger brothers, Blair and Douglas. The family home, Mount Pleasant, a graceful building set in about forty acres of woodland on high ground overlooking the town of Newtownards, was ideal for childhood play. The family was of the Presbyterian faith, although churchgoing was not assiduously practised. But the parents encouraged their children in sport and outdoor activities. William Mayne set an example, for he was a noted athlete and a champion cyclist. On a par with physical activities, the parents esteemed education as preparation for a career in business or the professions. When he reached secondary-school age, Blair attended the local grammar school, Regent House. In time the oldest brother, Tom, went into the family business with his father; Billy joined the Royal Ulster Constabulary; Barbara began a career in nursing; and Frances trained to become a teacher.

As a boy, Blair began to show superb hand-and-eye coordination; he excelled at ball games; and at an early age he was a marksman with a .22 rifle. He played cricket and rugby at school and he took up golf. In his aptitude for sport, he was not an exception in the family: Frances was a very good golfer, Billy boxed for the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Douglas played rugby and golf. Among field sports, Blair went in for fly-fishing, horse riding and deer stalking. Physically he developed very early: he grew in height and breadth of shoulder and was exceedingly strong.

At school he inclined more to the arts than the sciences. He responded sensitively to literature, but he had a poor opinion of the usefulness of his English-language curriculum, with its tedious parsing and general analysis, for when he was sixteen, he wrote in his diary that his studies had not given him the skill to write even a love letter.1 Socially he was rather shy.

When he was at school, sport played the dominant part in Blair’s life. And it was then that early indications of his leadership qualities first emerged. He played rugby for Regent House School and, shortly before his seventeenth birthday, he was picked to play for Ards Rugby Football Club Second XV; and in little over a year he was captaining the team. The following season, he captained the First XV. He was young to be appointed captain, but the feedback from his own performance the previous two seasons was positive and he had sufficient self-reflection to accept the responsibility and quickly showed that he was able to handle the challenge of leading older, more experienced players. For under his captaincy the club were winners in the B Division of the junior league; and when he was presented with a club honours cap, it was recorded in the club minutes that ‘His enthusiasm and thoroughness made him an ideal leader’.2

He chose an avenue for a career and in 1933 was articled to a firm of solicitors, T.C.G. Mackintosh of Newtownards; and in 1934, he matriculated at Queen’s University, Belfast to study law.

By the time he went to university, Mayne had reached physical maturity: he was six feet two inches tall, powerfully built and exceptionally strong. And it was when he was a student that he was encouraged to take up boxing. He was a heavyweight and showed promise: he was nimble on his feet, carried a heavy punch and quickly learned ringcraft, and within two years he was ready to fight for the Irish Universities’ crown. In August 1936, sport was the focus of attention across the world when the Olympic Games were held in Berlin, amid spectacle designed to impress foreigners with the achievements of the Third Reich. It was also the year that Mayne won the Heavyweight Championship of the Irish Universities. Next, he reached the final of the British Universities’ Championship, but was beaten on points.

However, he did not forsake his other sports. He kept up his golf – he had a handicap of eight – and in 1937 won the President’s Cup at Scrabo. He was also a member of his local swimming club. But rugby was his first love; he had been a rugby blue at the same time as he represented the university at boxing. Then in April 1937 his international career in rugby began when he was selected to play for Ireland in the final game of the season – the match against Wales. In this, his first international, he played well, and the following season he won two more caps for Ireland. But such a level of commitment came at a price: with him, like many high-achieving males at university, relationships with girls were relegated behind achievement.

But while 1937 was a memorable year for the family, with the third son representing his country, it was overshadowed by death. The oldest son, Tom, died from gunshot wounds. It may have been an accident, or it may have been suicide.

In April 1938, Mayne passed his final examinations as a solicitor and graduated from Queen’s University. But before he became a qualified solicitor, his sporting career soared: he was selected to join the British Rugby Touring Team, drawn from the four home countries – England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales – to tour South Africa. The tour lasted over four months, and the conditions were very gruelling. It is a mark of Mayne’s fitness that he played in twenty of the visitors’ twenty-four provincial and test matches. The first test was won by the Springboks, but, according to one South African paper, Mayne ‘was outstanding in a pack which gamely and untiringly stood up to the tremendous task’.3 The press in Newtownards reported that Mayne had been ‘generally voted the best lock forward ever seen in that country’; and after a game between the visitors and the Border XV it was said that he ‘again gave a brilliant display and was described as the most outstanding forward on the field’.4 The visiting team was referred to at one point as ‘the lions’ and in time that title was adopted as the British Lions. Although Mayne was at the peak of his form, by one of those anomalies of the game, he failed to score in the test series. The tour was a great success: the visiting team won the test series against the Springboks and eighteen of their twenty-four games; but they were ambassadors of sport as well, and both on and off the field they were in the limelight. They were made welcome wherever they went; sightseeing trips were arranged to a game reserve and they visited a gold mine.

On one occasion, Mayne joined a group of South Africans who were going out hunting and he shot a buck and brought it back to the hotel where the team were staying. When the team was at Pietermaritzburg, he had a drink one evening with a South African called Niddrey, a meteorologist, whom he was to meet again in different circumstances eight years later.5 At one stage of the tour, someone noted at the time that in discussing South Africa Mayne said, ‘South Africa has an ugly face. That must be to conceal her riches underneath.’6

During the final part of the tour, political concerns about Europe dominated the media in the UK, and disconcerting images appeared in newsreels and the papers of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain meeting Reichskanzler Adolf Hitler. But then the frenzy abated with pictures of the Prime Minister reassuringly holding up a piece of paper for the cameras; and the Sudetenland could now become part of Germany. One lone voice spoke out in the House of Commons on 5 October: ‘We have sustained a total and unmitigated defeat … And do not suppose that this is the end. It is only the beginning.’7 But Winston Churchill was not in government and had no power. For many it was a seven-day wonder, and life quickly got back to normal.

When Mayne was in South Africa, his progress had been closely followed at home, and on his return he was feted. That someone from Newtownards had been selected to play for the British Rugby Touring Team and had acquitted himself so well was regarded as an honour for the town. (It was the sort of response that was to be repeated later with his wartime achievements.) A reception was held for Mayne and he was presented with a gold watch. One of the speakers, Mr T. McCartney, said that what impressed him about Mayne was ‘his unfailing modesty and charm of manner’.8

Within weeks of his return, Mayne was playing rugby again. He joined a new team, Malone RFC, and was elected captain. Then his law career caught up with him. He was accepted as a solicitor at a Hilary sitting and joined the busy city practice of the Belfast firm of solicitors, George Maclaine and Company.9 He had been articled to T.C.G. Mackintosh for five years, and on 10 January 1939 they wrote of him: ‘Blair Mayne is a young man of very good instincts. He has pleasant manners, and is good-tempered and most obliging.’10

He continued playing for Malone throughout the winter of 1938/39. Then he was selected to play for Ireland again. The first game, on 11 February 1939, was against England, and two weeks later he played in the Irish side against Scotland. Ireland won both games. One report referred to two of the Irish forwards, O’Loughlin and Mayne:

Mayne, whose quiet almost ruthless efficiency is in direct contrast to O’Loughlin’s exuberance, appears on the slow side, but he covers the ground at an extraordinary speed for a man of his build, as many a three quarter and full back have discovered.11

The next game followed two weeks later, and Mayne again represented Ireland, this time against Wales on 11 March. It was an important match, for if Ireland had won they would have gained the Triple Crown. But the final result was 7–0 for Wales. It was to be the last time that Mayne wore the Irish jersey. On 6 March 1939, he had joined the Territorial Army. Newtownards was unusual in that, at the time, it had five different TA units. Mayne opted for and was commissioned to the 5th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Royal Artillery. There was now no denying it – war was imminent. But the rugby season closed with a game comprising an Irish XV versus one chosen from the British Lions’ touring party. The British Lions won, and Mayne scored a conversion with one of the last kicks of the match.12

Years afterwards, stories of Mayne being involved in fistfights on the pitch came into circulation – Marrinan had him felling three Welsh forwards – but these tales lack credibility. However, in a book by Gavin Mortimer, one of the Welsh team of the time tells of Mayne and Travers squaring up after an incident.13 Now, that seems more credible, for while rugby is a game of violent contact, gratuitous violence on the scale of Marrinan’s description was not part of the sport and would certainly have been written about at the time, for these games were closely reported. Then the frequency with which Mayne was selected to represent his country and his inclusion in a British team on a high-profile foreign tour means that the selectors had confidence in his reliability. And when he played for his local side, he tended to be elected captain, which indicates that he was looked on as a leader, not a maverick, during play. The risk of injury in top-class rugby was high but Blair once said to Douglas that no game ever had to be halted while he had an injury attended to – even on the occasion when it was discovered later that he had broken his left collarbone.

During his time at university, Mayne had not been particularly ideological, but he was passionate about Ireland. He had been born before the country was partitioned; he had strong feelings for its history and its cultures. Although he came from a Presbyterian background, he was not sectarian-minded; he celebrated St Patrick’s Day;14 and the international rugby team he played for was all-Ireland. When he was in the army and went overseas with the commandos, he took anthologies of poetry with him. Some of these poems he committed to memory; and under the desert stars at Christmas 1942, a group of soldiers were singing, each person making his own contribution. Mayne’s was to recite poems about Ireland, ‘and becoming so enrapt with their spirit that, even as he did so, his brogue became marked enough for us to find the verses hard to follow’.15 Later, when he went on to command the unit, Mayne followed the tradition of the ancient Ulster chiefs who accorded status to their bards and minstrels. Mike Sadler was one of Mayne’s colleagues and recalled of him:

He had a very unsatisfactory batman whom he kept on for years and promoted to sergeant, mainly, I think, because he was a very good singer and knew a huge range of Irish songs. Late in the evening he would be wheeled in and made to sing.16

However, when it came to assuming what Mayne’s standpoint was, some of his colleagues did not have a fine sensitivity for the Irish or the situation in Ireland. Pleydell, a medical officer, had some awareness of Mayne’s appreciation of the irony in the following tale:

Yes, Paddy was Irish all right; Irish from top to toe; from the lazy eyes that could light into anger so quickly, to the quiet voice and its intonation. Northern Irish, mind you, and he regarded all Southerners with true native caution. But he had Southern Irishmen in his Irish patrol – they all had shamrocks painted on their Jeeps – and I know he was proud of them; he never grew tired of quoting the reply given by one of the Southerners in answer to the question, why was he fighting in the war: ‘Why?’ he had replied. ‘Of course it’s for the independence of the small countries.’17

David Stirling was wide of the mark when, decades later, he told his biographer of an after-dinner story about Mayne which was predicated on the idea that Mayne was prejudiced against Roman Catholics.18 Both Pleydell and Stirling were in the position of outsiders giving their interpretations and making their judgements. The Northern Irish writer Lynn Doyle, who lived in the latter part of the nineteenth century and up until the middle of the twentieth, summed up this tendency and its failings: ‘Yet none but an Ulsterman can fairly criticise Ulstermen. The foreigner, looking at the surface of things, judges both sides too hardly.’19 Roy Farran, who came from the Roman Catholic tradition in Northern Ireland, and who was second-in-command of 2 SAS, appears to give some weight to Doyle’s argument, for he wrote that Mayne was not bigoted.20 Certainly, what Mayne himself wrote in his journal does not point to partisanship. He described a fellow Irishman, O’Sullivan, as ‘Gaelic Irish’; and he wrote that the two were in a club talking and drinking one Christmas Eve until O’Sullivan left to attend Midnight Mass. And although Mayne would not have described himself as a religious man, he had what Fraser McLuskey, the padre of 1 SAS, described as ‘a typically Irish respect for the Church’.21

Enduring characteristics of Mayne’s personality were formed in those early years. Some, such as standards of courtesy and charm of manners, of course, reflected his upbringing and were shared with his brothers and sisters. His employers and those giving expression to public recognition of his sporting achievements acknowledged such qualities in him. Nor were they mouthing shallow platitudes; for their assessments are compatible with what Mayne revealed of his attitude to others. Describing someone, he wrote ‘I like good manners in people.’22 But what there is no evidence of in these early years – it was to become more assertive with greater experience – was his implacable intolerance of people who were proud and conceited. Mayne, himself, although a high-achieving sportsman, was truly modest; it was a characteristic that never left him. For example, in a journal – where his only audience was himself – he wrote that he had been publicly honoured some weeks earlier, and he described the experience in one word, ‘embarrassing’. Those early years, of course, were also a time when lasting friendships were formed; and since his background was that of a small town, whose institutions he had attended and whose clubs he had joined, these friendships naturally crossed social boundaries.

As boys and as young men, Blair and Douglas were very close. The tone and content of Blair’s letters to Douglas are redolent of this, with allusions to their shared experiences of hard-drinking sessions, sometimes to shared values, or references to earlier philosophical questions they had discussed concerning fate, chance and providence. Douglas, too, was a keen sportsman, and after leaving school in 1939 he went up to university to study dentistry. He, too, gained a rugby blue and later, recommencing his studies after the war, became a golf blue.

A view that was expressed first by Marrinan and then echoed by others stated that Mayne was particularly close to his mother. Indeed, Bradford and Dillon, using Freudian analysis, attempted to break new ground by suggesting that, as a result of Tom’s death, Mrs Mayne concentrated her attention on Blair and that such a ‘boy who is his mother’s favourite’23 succeeds in life. When Tom died, Blair was twenty-two, at university and representing his country at rugby – rather late to be still at the early developmental stage. But the idea that he was very close to his mother is hardly supported by Mayne’s correspondence in the first two years after he left home. In one letter to his mother, he described conditions in his billet as near perfect because he could leave his wet clothes lying about without any women coming round tidying them up; in another he less than tactfully told her that he had recently met an old woman who reminded him of her; and he finished off a cheery epistle to his father with ‘Give my regards to your wife.’24 Now, there is no doubt that Mrs Mayne was a very strong character. Not only that, however, she had an extended period of parenting a large family: only Molly had left the nest, having married and moved to Belfast (Billy both married and divorced in 1933, and returned to the family home). So, from another perspective, the siblings may have considered that the mother was a bit of a dragon, but they were genuinely very fond of her.

However, of the personal qualities that were to become so important in Mayne’s military career, one, at least, can be traced back to his upbringing: his ability – an outstanding leadership attribute – to give support to his men in stressful situations. From a soldier’s acknowledging that Mayne gave him great confidence in those situations, to a general, visiting the unit, observing the high respect and regard in which Mayne was held by his men, all accounts point to a man who was secure in himself and in his early family attachments.

This misconception about Mayne having a special relationship with his mother appears to be connected with the assumption made by earlier writers that he had little interest in women. But their assumption is wrong. Mayne was certainly interested in women: he thought about them; he wrote about them; and he invited one or two of them out – as this narrative will reveal. All that can be inferred at this stage in his life is that he was naturally shy, and that his precocious physical development may have contributed to awkwardness in relationships. There was possibly a degree of sexual suppression in the family’s Presbyterianism, but that would be overcome in time as he gained experience. However, he committed himself completely to his sport – research shows that, during high-school and college years, men, more than women, see relationships as secondary to achievement and are more dismissive of attachment than women – and failed to practise personal interaction skills with girls when he had greatest opportunity, at university.

So Mayne was now twenty-four; he had been dependent for a prolonged period because of his education, and his commitment to rugby had delayed his qualifying as a solicitor. In the usual course of things, he would have expected to become established in the new law practice, leave home and, with the realism of the high-performing sportsman, knowing that his athletic days were short in number, he would have given some thought to his long-term future. But for a generation of young men and women the usual pattern was disrupted. On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Forty-eight hours later, Britain went to war.

The Territorial Army had already been called up, and on 24 August Mayne reported for duty. Officers from among these weekend warriors, who had not previously been in the regular army, had to be inducted in a short space of time into traditional military discipline. However, what these young soldiers had not anticipated was the disappointment of anti-climax after their initial enthusiasm over fighting for their country; for after the fall of Poland no aggressive land action was initiated by either side. Some seven months passed in this way in what became known as the ‘phoney war’. Certainly, there was fighting at sea and in the air, but it was a period of frustration for many. By the beginning of March 1940, the months of inactivity showed no sign of ending. Mayne was in Sydenham, and on 17 March, St Patrick’s Day, he celebrated in style, although he later confessed that the detail of it was a bit blurred in his mind.25 But this was to be the last St Patrick’s Day that he would celebrate in Ireland for seven years.

In 1939 it was not uncommon for friends to go along to the recruiting office together or jointly to complete their forms for the TA. That is what Mayne did: he and a friend of his, Ted Griffiths, applied to join the Royal Artillery Territorial unit, and his brother Douglas followed suit. And all three transferred to other units or branches of the services: Ted Griffiths and Douglas Mayne went to the Royal Air Force, and on 4 April 1940 Blair transferred to the Royal Ulster Rifles.

The Royal Ulster Rifles (RUR) up until 1923 had been the Royal Irish Rifles. But after the partition of Ireland a decision was taken to rename it. It seemed logical enough, since, historically, the regiment had recruited mainly from the province of Ulster. Mayne was posted to Ballymena, the RUR depot.

While he was in the Royal Ulster Rifles, Mayne became friendly with Eoin McGonigal. It was to become one of the closest friendships of his life. McGonigal’s family originally came from the south: his father had been a judge in the county of Tyrone; and the oldest brother, who was about thirteen years older than Eoin, was a senior counsel in Dublin. After the separation of Ireland, the family moved north (later it moved back to the south). Eoin and his older brother Ambrose went to Clongowes Wood College in Kildare. Eoin was a keen sportsman who played cricket and rugby. After leaving school, Eoin followed the same path as Ambrose and in 1938 matriculated at Queen’s University in the Faculty of Law. And at the outbreak of war the brothers joined the Rifles. Eoin was about four years younger than Blair. They may first have known each other through rugby circles or the legal fraternity, but it was in the RUR that they really got to know each other. When they were on leave, Blair and Eoin visited each other’s homes and met the other’s family. But they had joined up to defend their country, not to have an extended period of playing at soldiering and socialising, and they were restless.

Why, in the late spring of 1940, the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) asked for officers on attachment from the Royal Ulster Rifles in not spelled out in the regimental history of the Cameronians. What is known, however, is that there was a request. Douglas Mayne confirmed – so Blair must have told him – that it related to internal dissension in the Cameronians. This was not a bizarre situation: there is anecdotal evidence of a long-standing, friction-relief arrangement between these two regiments – the Irish and the Scottish Rifles – which may have been introduced by Lt Col R.M. Rodwell, a First World War veteran. Why Mayne and, it would appear from what transpired, McGonigal should have been prepared to go on detachment was probably simply to alleviate boredom. It was not a transfer to the Cameronians, it was a secondment. True, crossing the Irish Sea was scarcely comparable to an overseas posting, but life in the army had been frustrating for months. The reality, of course, was that it was no more stimulating in the Cameronians, as Mayne reported in a letter to his family.

But that was soon to change. In May, Germany invaded Denmark, followed by Norway; Britain responded and assisted the Norwegians, but the campaign was soon over. King Haakon and his cabinet fled to the UK. Germany then unleashed a blitzkrieg in France and the British Expeditionary Force was evacuated from Dunkirk. Churchill became Prime Minister, and within a month of his taking office he initiated action that led to the creation of an elite force within the army. Circulars requesting volunteers were sent to all the Home Commands. In response to the circular which was sent to Scottish Command, Mayne and McGonigal applied.

PART II

3

11TH (SCOTTISH) COMMANDO

Their country, which they have become soldiers to defend, is slipping away into the misty night and they are asleep. The place which will fill their thoughts in the months to come is gone and they did not see it go. They were asleep. They will not see it again for a long time, and some of them will never see it again.

John Steinbeck, Once There Was A War

Three infantry landing ships, Glengyle, Glenroy and Glenearn, slipped from the Tail of the Bank and into the Firth of Clyde late on the night of 31 January 1941. They set a course due west in convoy with some warships and a Cunard liner, its speed trimmed to that of the ‘Glen’ ships. Once it was considered that they were out of reach of aircraft bases in occupied Norway, the ‘Cunarder’ steamed at full speed without escort on its transatlantic run; the remainder of the convoy turned south. On board the three ‘Glen’ ships were No. 7 Commando, No. 8 (Guards) Commando and No. 11 (Scottish) Commando.

It was little over six months since Lt Col Dudley Clarke came up with the idea of such units in response to the prime minister’s challenge that new, aggressive and highly mobile units be created: ‘What’, asked Churchill, ‘are the ideas of the C-in-C Home Forces about “Storm Troops” or “Leopards” drawn from existing units?’1 Dudley Clarke had been turning over in his mind models of irregular warfare and, among other works, had been influenced by Deneys Reitz’ book, Commando, about Reitz’ experiences in the Boer War. Clarke outlined a scheme on one sheet of paper and submitted it to his boss, Chief of the Imperial General Staff Sir John Dill, who in turn informed Churchill. Within forty-eight hours, the idea was approved. A veteran soldier and journalist of the Boer War, Churchill did not demur at the choice of the name ‘Commando’. He gave his full support, and his only stipulation was that no unit should be diverted from the primary task of the defence of the UK. On 17 July 1940, he appointed Adm Sir Roger Keyes as Director of Combined Operations, within whose structure the Commandos would be placed. As a seal of approval, as it were, on these units, Churchill’s son Randolph volunteered for the Guards Commando and Keyes’ son Geoffrey for No. 11 (Scottish) Commando.

However, while the Boer Commando usually recruited from a town or district,2