5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

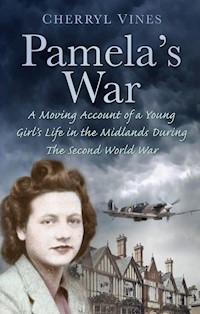

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

It is the third of September 1939. It is just after half past eleven in the morning. I am fifteen years and sixteen days old. The radiogram at my home, the Woodman Hotel in Clent, has just been switched off, the silence resonates around the room, and a deathly hush has fallen. The Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, has declared that, despite the best efforts of the politicians of the day to secure 'peace in our time', the inevitable has befallen us; despite pledges to the contrary, Germany has invaded Poland, Hitler has ignored requests to back down and so, therefore, 'Britain is now at war with Germany'. Minutes after the broadcast ends, my Father, Sidney Wheeler, goes quietly up to his room where he methodically loads three bullets into his First World War revolver. This is the true story of a fifteen-year-old girl's experience of the Second World War, based around her parent's hotel in a sleepy Worcestershire village. As war is declared, her father prepares three bullets for the invasion. He will shoot the family and himself when the Germans come. In their village, local Germans are imprisoned (guilty or not). The blackout is immediate and has tragic consequences. There is a court case over an alleged poker game. An abortion nearly results in tragedy. Handsome young airmen fly low over the hotel. Pamela has a premonition of death. The business fails. An air raid very nearly kills them all. She is called up first to factory work and then to the Land Army. She marries by special licence. As the war comes to an end she is living at home with her parents and a small baby, at which point she is just twenty-one years of age. Amusing and entertaining, surprising and often moving, Pamela's account vividly captures one family's life on the home front in Worcestershire.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

1. War is Announced

2. My Father’s War

3. The Incident at The Midland Hotel

4. Home from France and Marriage

5. A New Arrival

6. New Directions

7. My Dog Bonzo

8. The Cricket Team

9. A Successful Venture

10. Learning to Dance

11. Royal Secrets and the King’s Speech

12. Light Fingers

13. Day Trippers

14. New Friends

15. The Motor Car

16. Cigarettes, Ice Cream and Coffee

17. A New Hobby

18. Horse Riding with a Comedian

19. The Water Otter

20. Shopping

21. Leaving School

22. The Germans on the Hill

23. Family Rows

24. The War Effort

25. Rationing

26. Our Friendly Local Policeman

27. Cometh the Hour, Cometh the Man

28. The Home Guard

29. Party! Party!

30. Gas Attack

31. ‘Fronts’

32. The Blackout

33. My Low-Flying Friends

34. The Card Game

35. The Date

36. Music, Music, Music

37. The Abortion

38. Air-Raid Warnings

39. The Searchlight Team

40. Refugees

41. The Air Raid

42. Family War Efforts

43. Call-Up

44. The Wedding

45. The Land Army

46. The Ham in the Pram

47. The Telegram

48. The War is Over!

Copyright

Introduction

On her eighty-fifth birthday I take my Mother, Pamela Moore, for a drink at her old family home, The Woodman Hotel at Clent, now renamed The French Hen and stuffed with French antiques and bric-a-brac. She is not impressed.

She can clearly remember this building in its heyday in the 1930s, when it was in its prime. Freshly decorated and newly carpeted, full of customers drinking, smoking, laughing, living! Listening to dance music playing on the radiogram. I can almost feel their ghostly presence.

We leave by the back door and walk across the car park. ‘This,’ she says, ‘is where I saw David for the last time.’ David was the boy she loved and hoped to marry; this place is where they kissed for the first, and last, time. He is one of many young airmen who have laughed and joked and drunk and smoked in the room we have just occupied, whose young lives were cut short by war. Despite the fact that if he had survived I would never have been born, I weep for their lost love.

So this is how it starts; my curiosity to find out more about my Mother’s War, and her desire to record her memories before it is too late.

And what memories they turn out to be.

When we make the decision to record her reminiscences onto tape, we both assume it will be completed in a couple of hours. What she and I anticipate as a couple of foolscap sheets just keeps on coming, page after page, memory after memory.

She is just over fifteen years old and living at The Woodman Hotel when war is declared. Her father’s first act is to load a gun with three bullets – one for Pamela, one for his wife and one for himself – and is perfectly reconciled with using it to kill his family if the Germans invade. Pamela accepts that her father knows best without demur.

My mother’s life is shaped and reshaped by the war. Her youth is snatched away by circumstances over which she has no control. As she says, ‘I was forced to grow up very quickly.’ In not much over five short years, she goes from carefree schoolgirl to being a married woman with a baby and an absent husband posted overseas. On the way she enjoys happy times, suffers heartbreaking losses, has a near-death experience, gets married and has a baby, and celebrates when the Second World War finally comes to an end. Her accounts have made me realise why she is the incredible woman that she is today.

This is my mother’s story.

This is Pamela’s War.

Cherryl Vines, 2012

1

War is Announced

It is Sunday the 3rd of September 1939. It is not long past eleven in the morning. I am fifteen years and sixteen days old.

The radiogram at my home, The Woodman Hotel in Clent, has just been switched off, the silence resonates around the room, a deathly hush has fallen.

As usual on a Sunday morning the place is full. Weather-worn farm workers lounging in the front bar, dapper businessmen who have escaped the Sunday morning chores to sup a few pints of ale while their long-suffering wives stay at home to prepare the meal. The chef, who wandered out from the hot kitchens just a few minutes ago, wiping his hands on his crisp white apron, is vaguely annoyed that his pre-lunch routine is being disturbed, little knowing how much his life is about to change. The carefree chambermaids have scampered down from their bed-making duties, wondering what on earth can be so important to keep them from their work. My Mother, my Father and I, we are all there to share this terrible piece of news – news that will change our lives forever.

We have all listened to the broadcast in stunned, horrified silence. Although summer is just coming to an end and autumn has barely started, with the golden leaves still stubbornly attached to the trees, there is a chill in the air.

We are in a state of shock, having heard confirmation of news that many have dreaded for months. The Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, has declared that, despite the best efforts of the politicians of the day to secure ‘peace in our time’, the inevitable has befallen us; despite pledges to the contrary, Germany has invaded Poland, Hitler has ignored requests to back down and so, therefore, ‘BRITAIN IS NOW AT WAR WITH GERMANY’.

There is a collective sigh. ‘Never mind,’ someone says, trying to lighten the mood, ‘it’ll all be over by Christmas!’

If only! We were not to know it, but there would be six long Christmases of fear, deprivation and shortages before this awful war was over. The Prime Minister has requested that we all play our part with calmness and courage; little do we know at this time just how much courage it will take to get us through this dreadful ordeal.

Minutes after the broadcast ends, my Father, Sidney Wheeler, goes quietly up to his room and prepares for a potentially murderous act.

In a bedroom of the hotel in this quiet Worcestershire village, he methodically loads three bullets into his First World War revolver.

His intention, should the Germans invade, is to shoot his beloved family.

One bullet is for me (Pamela, his only child), the second for his wife Marie (my Mother) and the final one will be used to remove him from the horror of what he has just created through his actions.

He has given this plan a great deal of thought. A veteran of the Somme, he knows the Germans, he knows what is coming, he knows what war does to a man and he sees this act as perfectly reasonable. When the Germans come he will be ready!

Wrapping the loaded weapon carefully in a large cotton handkerchief, he stows it away. Pushing the drawer closed, he turns the key and prays that he will never be forced to have to use it.

Never having experienced the worries and deprivations of war and little knowing what lies ahead, my concerns at this time are rather more focused on my return to school for the new autumn term, getting together my uniform and books and preparing for the forthcoming and dreaded School Certificate.

Though I am not to know it just yet, Herr Hitler is soon to rid me of the requirement for, or the worry of, any of these things.

2

My Father’s War

He has tried hard to put behind him the terrible sights and sounds of the battlefields of the First World War. He rarely speaks about what has happened.

But this ‘War to end all Wars’ has seen him witness many, many dreadful barbarous acts, including the murder of his best friend, shot through the head by a German leaving a captured bunker. He has never said but I suspect that the perpetrator of this deadly act did not live long after this outrage. He has also witnessed the sickening experience of seeing one of his pals walking beside him who, having stood on a mine, is quite literally blown to kingdom come. There is nothing left of him at all. Absolutely nothing!

And there was so much more.

The rats, the lice, the mud, the blood, the stench of life (and death) in the trenches – most of the troops spending hours up to their knees in water until the command, given by the sound of a whistle, to go over the top to attack – and never knowing who would be next to die. And as if the bombs, the mines and the bullets are not enough of a threat, there is also the terror of mustard gas, which, creeping silently, blinds and kills. When he becomes an Officer he has an additional pressure to deal with. He carries forever the guilt of sending men to their deaths; for making just one wrong call can terminate a life, or many lives, on his say so alone.

The whole vile experience of his war which, together with that of his Birmingham pals, has been entered into with such naïve hope, has culminated in the death of a generation of idealistic young men. They have joined up town-by-town, village-by-village, and since troops are gathered together on a geographical basis, many that fight together die together.

Thus whole villages are robbed of their men – their fathers, sons, brothers and sweethearts; families frequently lose all of the men that they send for sacrifice, as they fight side-by-side – so they die side-by-side.

An entire generation gone forever.

A man does not easily forget these things, or forgive them, EVER.

I think it is true to say that my Father, at this stage in his life, is not terribly fond of the Germans. And never will be.

There are lighter moments in his war, amongst which is the hugely anticipated arrival of the post from home. Without fail, his mother packs and posts a parcel for her darling boy every single week, which arrives without fail every single week, no matter where in Europe he is. The contents of this parcel are consistent and predictable, and one imagines him being teased mercilessly by his fellow soldiers as he unwraps the contents, first revealing the new pair of underpants and then, rolled up inside, the bottle of Lea & Perrins Worcester sauce; the same contents every time. This spicy little bottle of relish proves to be a lifesaver for him since this condiment, when added to the virtually inedible trench rations, makes them almost palatable.

There is naturally also the camaraderie of friends, the sarcastically dark army humour that helps them all get through the unimaginable experiences that war forces upon them. There are also the football matches that take place between the British troops, giving a little light relief in the midst of so much misery, allowing a little normality in the midst of so much madness. He always loved football and won medals for games played as a junior. Sadly for him, the photographs of the time show him in uniform beside his football player troops; he clearly has to settle for reflected glory from now on.

Some time between joining up and his commission, he is temporarily invalided home with rheumatic fever. This is when his lifelong admiration of the Salvation Army begins. For it is they that provide his welcome home from the ship with a cup of tea and a cigarette, a kindness that is never forgotten.

3

The Incident at The Midland Hotel

Although he joins up as a private, the war sees my Father promoted quickly through the ranks to Officer status.

This state of affairs could have easily come to a very abrupt end following an incident at a local Birmingham Hotel when he is home on leave. By nature he is a very gentle man, but the war has toughened him up. He is not prepared to put up with any nonsense, not after all the things that he has been forced to witness.

Wearing his very smart dress uniform with its shiny trouser stripes, he is here to relax, but is being loudly harangued by a local ‘Hurray Henry’ who clearly has chosen not to offer himself up for sacrifice in this Great War when he had the chance, and who has probably consumed far too much alcohol already that evening.

The rude remarks and barracking have continued for some time. My Father has very nearly had enough.

‘I say my man are you attending here?’ says Henry (for this is what we shall now call him), accompanied by laughter from his equally drunken companions. ‘No,’ says my Father, incensed at the suggestion that his smart uniform is that of a waiter, ‘but I can soon attend to you!’ During the ensuing scuffle, Father and Henry struggle next to the open first-floor window of the hotel. Seconds later, much to the horror of the onlookers, my Father’s opponent is flying towards his doom on the pavement, well over thirty feet below.

However, it is clearly Henry’s lucky day for, instead of crashing to almost certain death or very serious injury on the ground below, he finds himself cradled in the safety of the large awning hanging (happily for him) beneath the window from which he has just been ejected; this breaks his fall and very probably saves his life. Quite how Henry escapes from this canvas cradle is not recorded, for by now my Father is well on his way out of the back door of the building.

The barman, who, having witnessed the whole series of events and whose sympathies clearly lie with my Father, removes him quickly from the scene before he can be identified; an act that probably prevents his war culminating in a rather different conclusion.

Many years after this event, my Father returned to the same hotel and is recognised by the very same barman still working in the bar. They discuss the event, one that has never been forgotten. He confirmed that ‘Henry’ survived the incident with only his ego damaged: he was considered by all to be a drunken boor who deserved to be taken down a peg or two, and who more than deserved the treatment that he received.