Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

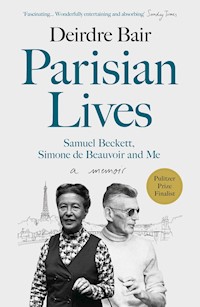

A The Times & Sunday Times Book of the Year 'Fascinating... Wonderfully entertaining and absorbing' Sunday Times 'Gripping... A story well told.' New York Times Book Review Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Biography 2020 In 1971 Deirdre Bair was a journalist with a recently acquired PhD who managed to secure access to Nobel Prize-winning author Samuel Beckett. He agreed that she could write his biography despite never having written - or even read - a biography herself. The next seven years of intimate conversations, intercontinental research, and peculiar cat-and-mouse games resulted in Samuel Beckett: A Biography, which went on to win the National Book Award and propel Deirdre to her next subject: Simone de Beauvoir. The catch? De Beauvoir and Beckett despised each other - and lived essentially on the same street. While quite literally dodging one subject or the other, and sometimes hiding out in the backrooms of the great cafés of Paris, Bair learned that what works in terms of process for one biography rarely applies to the next. Her seven-year relationship with the domineering and difficult de Beauvoir required a radical change in approach, yielding another groundbreaking literary profile. Drawing on Bair's extensive notes from the period, including never-before-told anecdotes and details that were considered impossible to publish at the time, Parisian Lives is full of personality and warmth and gives us an entirely new window on the all-too-human side of these legendary thinkers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 621

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PARISIAN LIVES

ALSO BY DEIRDRE BAIR

Al Capone: His Life, Legacy, and Legend

Saul Steinberg: A Biography

Calling It Quits: Late-Life Divorce and Starting Over

Jung: A Biography

Anaïs Nin: A Biography

Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography

Samuel Beckett: A Biography

Published by arrangement with Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC.

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Deirdre Bair, 2019

The moral right of Deirdre Bair to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-265-4

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-267-8

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-266-1

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-268-5

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

FOR AILEEN WARD,

Mentor and Fr iend

PREFACE

Whenever / meet someone new and tell them that I have written biographies of Samuel Beckett and Simone de Beauvoir, their first question is usually “What made you choose those subjects?” I’ve honed a ready answer over the years, one designed to be brief and polite and to let me change the subject. “They were remarkable people,” I say. “Truly extraordinary. Great privilege to have known them.” Most of the time I don’t get away with it, and the question that routinely follows is “What were they really like?” That one is never easy to answer.

Over the years I wrote several other biographies about equally fascinating people, but the interest in Beckett and Beauvoir remained out of proportion to all the rest. With every lecture or seminar, I found myself fielding questions about what was it like to be with them, and what did we talk about, and why did I write the books as I did. I was bombarded with remarks along the lines of “Weren’t you awestruck, terrified, humble, wowed”—you pick the adjective here—“to be in the presence of Samuel Beckett and Simone de Beauvoir?” Yes, I admit; yes, I felt all those emotions and many more besides. I can’t count how many times I was asked to sing for my supper at dinners and parties, or relate how hard I searched for anecdotes to amuse other guests without inappropriately revealing anything personal I had come to know about these literary giants.

But the questions persisted, and I began to think that perhaps—someday in the far distant future—perhaps I might write a little book, a “book about the writing of the books.” The original idea was to write something primarily for scholars and writers that would cover all my biographies, to concentrate on the decisions I made when dealing with structure and content, or how I worked in foreign archives and languages, or how I dealt with reluctant heirs and troublesome estates. Each time I suggested this possible project, even to fellow biographers or academics, the response was always “That’s all very nice, but please just tell us what Beckett and Beauvoir were really like.” And for many years that was something I simply could not bring myself to do.

I wrote those two biographies during the most eventful years of my own life, and to write about Beckett and Beauvoir meant that I would have to write about myself as well. If I described the professional decisions that I made, I would also have to describe the brash young woman I was then: a journalist not yet thirty who became an accidental biographer, one who had never read a biography before she decided that Samuel Beckett needed one and she was the person to write it. And I would have to tell of a somewhat wiser woman a decade later, who formed a feminist consciousness during tumultuous years when she worked hard to stay married, raise children, keep a household running, forge an academic career, and scrounge enough money to go to Paris to confer with Simone de Beauvoir—because Simone de Beauvoir appeared to be the only contemporary role model who had made a success of both her personal and her professional lives, and I was searching desperately for someone to tell me how to do the same.

My writing life began as a reporter for newspapers and magazines. Even though it was the era of the New Journalism, I never adopted those techniques and kept myself scrupulously out of everything I wrote. That decision was largely made for me by the fact that I wrote hard news much of the time—from actions of the zoning board of appeals to city council shenanigans, the sort of thing that allowed me to concentrate on the story at hand and not on the role I played in getting it. When I began to write biography, a biographer friend who also started in journalism told me how she melded her old career with the new one: “Biographers are essentially storytellers. So, then, tell the story, but stay the hell out of it.” Since that was my natural impulse, this approach suited me just fine until I became both source and subject.

In the last several years, I was contacted by several biographers whose subjects figured in my books, and thus in my life. I gave them interviews in which I described my interactions with their subjects, and I gave them letters, photos, and other documents to support what I told them. Imagine then my horror when their books were published and I was quoted and thanked effusively but with everything they attributed to me either twisted or subverted. I checked their notes to see if they were using multiple sources, for if so, the weight of information from others might explain how they had changed my testimony. But no, I was their only source, so it was obvious that they had contorted my words to support their theory or thesis. It put me in a terrible position, because much of what they wrote was simply not true. That was the moment when I began to give serious consideration to committing my own version of my working history to print, to set the record straight as I remember it and to let future generations of readers assess it and decide for themselves whether I was an objective witness and a reliable narrator. Or not.

And yet I was still not ready to confront my own story. I am sure I bored my sister-writers in the Women Writing Women’s Lives seminar at CUNY, when I sought their counsel for the better part of a year as I asked repeatedly how I could bring myself to reveal so much that was personal, not only about Beckett and Beauvoir but about myself. For every embarrassing or unpleasant or unsavory aspect of their behavior, mine was at least doubly so. I had begun to write biography as a curious combination of seasoned, hardened journalist and total novice in the genre. Did I really want to put all the mistakes I made out there for the world to see? My dilemma was expressed perfectly when Margo Jefferson spoke to the seminar about her memoir, Negroland, and said the self she wanted to put on the page was the hardest to write about: “How do you reveal yourself without asking for love or pity?” How, indeed.

I found an interesting example of my problem at a lunchtime talk at New York University’s Institute for the Humanities, when Phillip Lopate said it took him thirty-one years to write a memoir about his mother, because every time he approached the truth he found himself backing away from it. I suppose I was more fortunate, because for me approaching, backing away from, and revealing my own truth took only nineteen years.

How then to construct my story? Of my three subjects—Samuel Beckett, Simone de Beauvoir, and myself—the first two became much easier to remember and recount after I waded through the ceiling-high stacks of boxes of papers in my storage room, what the neighbors call our local fire hazard. Everything I needed to jog my memory was there, from interview transcripts to news clips, photos, and correspondence; looking through this material helped me to remember how the decisions I made when writing the biographies were rooted in the facts. A central tenet of my writing credo is that if memory is to serve as one of the two basic pillars of support for any biography, it must be coupled with fact. But what about me and my story? Where would I find the facts of my life to balance my memories?

I solved that problem when I found boxes I had entirely forgotten, those containing what I called the Daily Diaries, or as I abbreviate them here, the DD. It was a shock to find the big red “page-a-day” books where I wrote down everything and anything connected with the work I did for the biographies. I did not remember how much detail I had confided to those notebooks, everything from capsule profiles of the people I met, to long philosophical meditations on my life, to the wide, colorful range of emotions (negative as well as positive) I felt for my subjects. Here was the record of the several selves I would have to portray in this book, from the neophyte to the mature woman who reads these journals now with a deep appreciation for how those experiences helped her to become who she is today. That would be the most important self, the one who explains every step of the process.

With the DD in hand I could buttress and fortify so many aspects of the shifting and varied self who displayed her emotions and passions those many years ago. Applying the filter of time to these in-the-moment accounts lets me be present but also lets me distance myself, and to create another self, one better suited to a dispassionate telling of the most objective tale possible. Once I mined these layers, I knew I could write this curious hybrid of a book, a “bio-memoir” that does indeed tell my story, but only as it first tells the story of my subjects and how I wrote their books. I was able to combine literary imagination—all the things I thought then, later proven right or wrong—with the authority of facts as time has revealed them. The reader will see me, I hope, standing above or outside my story, looking down on all the players in it, as I thought of them then, as I think of them now.

I think my years of hesitation led me to wait for the perfect moment to tell this story. Enough time has passed that I can set the record straight (as I see it) with little risk of hurting anyone; most of the people I wrote about have died, and the survivors I know of are unlikely to be surprised by what I write here. Even so, writing bio-memoir has not been easy, particularly because so much writing today is self-referential and it was a struggle to find my place within shifting genres. Memoir is no longer bound by the need for absolute truth, nor is it constrained by the concerns of decorum and decency that prevailed in our recent past. We live now in an age of indecency, when nothing is off-limits. Fiction is often prefaced with terms like “auto,” “self,” and “reality,” a practice that allows novelists to creep under the fences and invade the turf of autobiography. Autobiographers, meanwhile, no longer hesitate to fictionalize the history of others. And contemporary biographers who find little or no information about their subjects feel scant compunction about inserting themselves into lives in which they played no part, either as authoritative characters or as commentators.

I was well aware of all these genre-boundary breakdowns and did my best to avoid them, but on the few occasions when I crossed borders, I tried to explain my reasons. For me, biography will always require the writer to be “the artist under oath,” as the critic Desmond MacCarthy decreed, and that was how I tried to write this hybrid of memoir and biography. There was no hiding, and sometimes it was painful. Writing was a slow process of discovery; I have always lived in the present day, and to recall my professional coming-of-age was to explore an almost unknown country that was long gone, one that I had not paid much attention to but one that was now demanding thorough examination. I paraphrase here the French writer Sainte-Beuve, who believed that you never understand a writer’s work until you understand her life. The only way I could understand mine was to get outside myself and make myself both subject and object, to discover those selves as I went along, in real life and on the page. Call it serendipity, synchronicity, happenstance, or accident—whatever it was, I became the biographer of two of the most remarkable people the world has ever known, and those adventures became this book.

PARISIAN LIVES

1

“So you are the one who is going to reveal me for the charlatan that I am.” It was the first thing Samuel Beckett ever said to me on that bitter cold day, November 17, 1971, as we sat in the minuscule lobby of the Hôtel du Danube on the rue Jacob. I had gone to Paris at his express invitation, to meet him and talk about writing his biography. We were originally scheduled to meet on November 7, and for ten days I had no idea where he was, because he never showed up and never canceled. When we made the initial appointment, he told me I should phone when I arrived in Paris on the sixth and we would confirm the time and place. I was to call precisely at one o’clock, because he disliked the telephone and answered only during the hour between one and two. When he did not pick up, I spent that hour phoning every five minutes, becoming more anxious and upset each time as I let it ring and ring.

In those days Paris had a system of pneumatiques, little blue messages that looked like telegrams and went through tubes all over Paris, to be delivered within the hour. I wrote several little “blue pneus” during the days that followed, and still I did not hear from Beckett. I had no idea what to do, and fluctuated between disappointment and fear that he was avoiding me because he had changed his mind about cooperating. And yet I did not think anyone could be so deliberately callous and cruel, so I set about keeping other appointments related to the book I wanted to write until I could find out what was going on with him.

On November 16 he phoned my hotel to arrange a meeting for the next day. He apologized for going off without contacting me and said he would explain in full in person. On the phone he said only that he had been felled by a terrible cold and was so weak and debilitated that he had allowed his wife to take him to Tunisia for sun and warmth. They left in such a hurry that he had not been able to cancel all his appointments. I was relieved beyond measure.

The Hôtel du Danube was not the chic and expensive place it is now. In 1971 it was a $19-a-night shabby dump favored by poor graduate students and budget tourists. The hotel was in such poor repair that there had been neither heat nor hot water for the twenty-four hours before our meeting, so there was no coffee at breakfast and no hot bath. The only staff around to deal with disgruntled lodgers were the two Portuguese maids, whose French accents were so incomprehensible that I did not know whether the inconvenience was the result of yet another of the many utility strikes that roiled Paris that winter or if the decrepit plumbing and heating had simply given out.

I was hungry, cold, and desperately in need of caffeine, but I was too nervous to go out to get it. Because of the missed connections during the previous week, I was superstitious enough to think that if I left the hotel, some terrible accident would happen to make me miss my first meeting with Samuel Beckett. So I decided to bundle up and wait for his arrival in my cold room, where, with the noisy radiator gone silent, the only sound was my growling stomach.

At precisely two o’clock, the time he said he would arrive, my phone rang. “Beckett here,” he said in the high-pitched, reed-thin nasal voice I would come to know well. I mumbled something into the receiver as I slammed it down and bolted for the stairs to the lobby, where I found Samuel Beckett peering intently into the gloom through which I made my clattering descent.

I recognized his hawklike visage at once, his slightly crooked nose and the tuft of white hair that reared straight up from his forehead. I don’t think I have ever met anyone whose physical reality was so accurately captured in photographs. He was a tall man, but I was also struck by the discrepancy between his elongated torso and his legs, which appeared short in comparison. We shook hands and murmured greetings. He was bundled against the weather in a sheepskin jacket and heavy white Irish-knit sweater with a high turtleneck collar. It reminded me of the ruff worn by British Cavaliers in earlier times, particularly after I gestured toward the lobby’s tiny table and two chairs and he swayed toward them, sweeping into one with a courtly half-bow. I took the one opposite and smiled, waiting for him to begin the conversation. There was no other furniture in the lobby, and the arrangement worked fine for Beckett’s diminished vision, but it was so tight that our knees touched underneath, even though we struggled to situate ourselves so they would not. I knew that he had recently had eye surgery, but I did not know that his general vision was still impaired and that his peripheral vision had not returned at all. The only way he could see someone was to sit or stand directly in front of them, as close as decorum would allow.

So he stared at me intently, because it was the only way he could see me. I thought perhaps he was puzzled by my heavy coat, woolen hat, and gloves, all of which I had been wearing since I got out of bed that morning. I thought he might be afraid that I was dressed for the outdoors because I intended to spend the rest of the day trailing after him all over Paris, so I quickly explained about the hotel’s lack of amenities. It did not have the effect I intended, which was to put him at ease, because I had to shout over the two Portuguese maids, who were busily trading obscenities in two languages right next to us as they pulled at opposite ends of an old treadle sewing machine that each was determined would be hers.

When they were gone and quiet fell, Beckett and I managed to arrange our legs on the diagonal so they did not brush. He took out a lighter and a pack of something brown, whether tiny cigars or cigarettes I was too nervous to determine. He fidgeted with the lighter, all the while staring in silence straight at me through the pale blue “gull’s eyes” he gave to Murphy, the hero of his first published novel. I was disconcerted by what I mistook for the appraising boldness of his gaze. As he fidgeted with the lighter, I picked up his packet of smokes and twisted and turned it in my hands. In one swift motion, Beckett reached across the table, snatched the packet, and spat out those first alarming words, that I would be the one to reveal him as a charlatan.

I was struck by what I thought was scorn in his voice and a cold lack of expression on his face, and I was unable to speak. The silence deepened as he stared and stared—and stared. I don’t remember my exact reply to such a stunning declaration, but it was probably something stammering, perhaps even silly, for I was a young woman proposing an ambitious project for which I wanted his cooperation, even though I had no idea how to go about it. Several months earlier I had sent Beckett a letter volunteering to write his biography, and to my amazement he had replied immediately, saying that any biographical information he had was at my disposal and if I came to Paris he would see me. Imagine then, my shock at his initial greeting.

Beckett saw the look on my face and, courtly Old World gentleman that he was, began to stammer an apology for having upset me. No, no, I insisted, I was not upset. He had just taken me by surprise, for after all, I was in Paris at his invitation. What I remember most clearly of that awkward beginning is how so many thoughts raced through my mind. I wondered what sort of game he was playing and whether his invitation was little more than a bait-and-switch meant to sound me out before deciding whether—or how—to put insurmountable obstacles in my way so that I would never write the book. After all, wasn’t he one of the most secretive and private of all writers, one about whose personal life almost nothing was known?

Then there was the business of him calling himself a charlatan. I struggled to comprehend how he could possibly believe that his writing was a joke that had somehow gotten beyond his control and managed to hoodwink the reading and theatergoing public. He was a Nobel Prize winner whose novels and plays had changed literature and drama irrevocably in our time, so how could he think of himself as a sham and a hoax? Perhaps this was just his way of testing me, to see if I would respond with flattering and insincere disavowals intended to curry his favor, to determine how serious I was about writing an “objective” biography, as I had stated in my letter.

All this went through my mind in a matter of seconds as I dropped my head into my hands and said, “Oh dear. I don’t know if I’m cut out for this biography business.”

His demeanor changed immediately, as did his tone of voice. “Well, then,” he replied, “why don’t we talk about it?”

Beckett seemed nervous as he launched into an apology for having to meet me in midafternoon instead of inviting me for drinks or a meal. He apologized several times, each with increasing agitation, for needing to rush off as he had to do, saying how he hoped that this long-delayed rendezvous had not inconvenienced me and explaining again about how the last-minute trip to Tunisia had caused his appointments to pile up.

He spoke kindly when he asked me to tell him why I wanted to take on “this impossible task” and was smiling when he said, “I would have thought a young woman like you would have more interesting things with which to amuse herself.”

And so I began to talk, most of the time coherently, because I had practiced what I wanted to say, memorizing the key arguments. Even so, there were times when I lapsed into unorganized or unrelated remarks, because there was so much I wanted to tell him. I did not touch on any of the many questions that I wanted to ask about his life or his work. Instead I told him a little bit about myself and a lot about the current state of academic theory in the United States, particularly at Columbia University, where I had written a dissertation about his life and work, for which I would receive a doctorate in comparative literature in spring 1972. He sat there quietly, giving me no visible sign that he was receiving my remarks in any way other than just listening—keenly, deeply, and intently listening. In years to come, he often responded to things I told him in this same neutral manner, and each time I found it as disconcerting as I did on this first occasion.

However, he must have found what I said interesting enough. Time passed, and the hour he said he could spare lengthened into almost two before he realized that he was now behind schedule for the rest of his appointments. Before leaving, he made the remark that has since come to haunt me: “I will neither help nor hinder you. My friends and family will assist you and my enemies will find you soon enough.” He began to gather his things and said we could meet again in a day or two, but he could not confirm the time or date just then and would have to phone later. And with that he was gone, leaving me to wonder when (or even if) another meeting was going to happen.

I went back to my room, and as I opened the door, I heard the radiator cranking on. With the promise of heat, I decided that coffee could wait a little longer. Beckett had made so many remarks—cryptic, sarcastic, friendly and open, evasive and unfriendly—that I wanted to record them while I still remembered what he said. It was the first of the many times after our meetings that I hurried back to a place of splendid isolation where I could transcribe everything I retained. And after this first meeting I also needed to recall everything that I had told him about myself.

“You need to know about me,” I had insisted. “Before we get started on a biography, I can answer your question about why I want to write yours only by telling you who I am.” And so I had. Looking over my notes, his remark about his friends, family, and enemies resonated. Indeed, in the seven years to come, those people did exactly what Beckett had said they would.

2

A circuitous route had brought me to that tiny round table in the shabby hotel. I went to Paris because I had the grandiose idea that I would be doing the literary world a service by demonstrating in a biography (as I had done in the dissertation) that Samuel Beckett was not (as the reigning view in the academic community then held) a writer steeped in alienation, isolation, and despair, but rather one who was deeply rooted in his Irish heritage and who portrayed that world through his upper-class Anglo-Irish background and sensibility. Such a high-minded mission had taken root in 1969, the year I left a newspaper career to enroll in graduate school. At the start I was not really committed to a life of scholarship but was there only because I needed a break from the pressures of being a beat reporter on constant call in the world of print journalism.

I spent the decade between my undergraduate and graduate education writing for magazines (Newsweek very briefly) and newspapers (at that time the New Haven Register), specializing when I could in short features and in-depth profiles of local luminaries. News doesn’t happen just during business hours, which made life especially difficult for a woman who had married directly after university, was the mother of two small children, and was the main family support with a husband in graduate school. I was in my late twenties and was exhausted from trying to combine a career with family life, and I felt myself quite alone doing so. Very few married women in my social circle held jobs in the greater New Haven area, where I lived, simply because they were not expected to. Their husbands were either academic or professional men, and if any of these women did work outside the home, it was at something temporary, just until their husbands established careers. Most of those who had jobs did not have children, while I already had two. I was an anomaly who did not know that I was “trying to have it all,” for the phrase had not yet found its way into women’s consciousness. I knew only that I was burned out. I could not go on volunteering at the PTA and the Junior League while also carving out time to bake cookies for my children’s classes or provide refreshments when it was my turn for my husband’s graduate study group. Nor could I participate in the local newcomers’ group dinner parties, because I couldn’t find the time to prepare the elaborate gourmet dishes; also, they ended late and I had to get up early to be at the police station by 6 a.m. to check the police blotter before I went into the newsroom to write that day’s feature story. Trying to be and do it all had become too much.

When the opportunity of a writing fellowship in a newly formed program at Columbia University’s School of the Arts came along in 1968, I embraced it. I thought it would be a peaceful respite for several years during which I could read novels and write about them without the pressure of daily deadlines. I thought it would enable me to recharge while also sharpening my skills for a writing career as a cultural critic in journalism. At that time it never occurred to me that I might become a professor, let alone a biographer.

My first year at Columbia coincided with the student protests in spring 1968. “Come on,” shouted one of my new classmates as I sat in the sun on the steps before the statue of Alma Mater on a sunny April day, “we’re going to seize Schermerhorn Hall.” I couldn’t, I said with regret, because I had to go home to New Haven and cook dinner for my children. It was clear from the start that I was a most unusual graduate student, a reputation I cemented when I told my classmates that I did have to rush home but first I had to stop at Saks for a sale on purses. From that day forward they joked that I was the “Bloomingdale Marxist,” never mind how many times I corrected them about the store’s name. This is a rather embarrassing story that I still blush to tell, but I do so because it shows how uncommitted I was to a life of serious scholarship, and how, even after one year of course work, I still thought of myself as a journalist in search of a story.

I loved being in the School of the Arts, where indeed I did get to sit around and read novels to my heart’s content. But I was not learning anything new in the nonfiction program, where my instructors, many of whom had not seen the inside of a newsroom for years, were teaching my classmates somewhat outmoded explanations of what I had actually been doing every day for almost a decade. The only part of the program that energized me was the literature courses I took in the Graduate School, where I read Joyce’s Ulysses line by line with William York Tindall and modern poetry with John Unterecker. The 1968 uprising threw the university into crisis, but for me it brought resolution. I discovered that I wanted to read literature, not listen to someone tell me how to prepare copy. I already knew how to do that. I don’t exaggerate when I say that I had fallen in love with reading and talking about literature, and somehow I wanted to find a future career that would let me continue.

And so in the fall of 1968 I went to John Unterecker, who was then chairperson of the graduate Department of English and Comparative Literature, and I said, in effect, “Let me in.” Instead of spending a second year in the School of the Arts, I wanted to transfer to the Graduate School to get a master’s degree, with the possibility of continuing on to the PhD. I thought that no matter what my next job would be, if I became a woman who held an advanced degree, whatever I wrote would command authority. I saw myself becoming a writer more than a teacher, but if a professorship would further my writing, it seemed an excellent way to proceed.

John Unterecker was perfectly willing to sponsor the transfer, because the tuition covering the master’s degree was already paid, but he cautioned that I would have to bring my own money if I wanted to study beyond that. The Graduate School’s admissions committee would probably be reluctant to admit a woman approaching thirty, married and with two small children, and the scholarship committee surely would not fund her. He said the committee members making these decisions were all men and they would probably think of me as a gamble that would not pay off. And besides, I would be taking a place that could better be given to a man. I nodded in agreement, for at that time I agreed with cultural norms and thought this was a perfectly reasonable attitude. I thanked him kindly and set out to find a way to pay my tuition so I could enroll in the doctoral program.

My quest began at a fortunate moment in women’s history, when the lack of women professors and administrators in higher education became a subject of national concern. The St. Louis–based Danforth Foundation decided that something had to be done to rectify the situation, and in 1965 a fellowship program was set up for “mature women” who could get themselves admitted to a graduate school (no easy task in a male-dominated world). These women were expected to work hard and study fast enough to earn advanced degrees in a few short years, after which they were expected to glide easily into full-time positions in colleges and universities. The Danforth Graduate Fellowships for Women was a remarkable program, and everyone I know who became a GFW alumna will tell you how it changed her life. It certainly changed mine.

Even though staying at Columbia meant continuing the commute on the old New York, New Haven, and Hartford trains, then taking the shuttle from Grand Central to Times Square and the subway to 116th Street—two hours door to door in each direction—I never thought of taking my GFW to Yale. You could say I was put off by a conversation with the chair of the Medieval Studies Department, who once told me casually at a party that I would never be admitted to any graduate school because I was “too old [I was twenty-seven at the time], too poorly prepared [I was a Penn honors graduate], and ... a faculty wife [of a teaching graduate student].” But such banal chauvinism didn’t touch on my real reason, one that I later learned was common among women throughout the 1970s. I was afraid I might fail, and if I did, everyone in my circle would know about it. I reasoned that if I failed at Columbia, I could save face by saying that I had decided to drop out because commuting proved too difficult. That was how women thought in those days, even women like me, who had been on the front lines of their professions and subject to all sorts of rejections, insults, and abuse. Looking back, my reasoning may have been faulty, but it turned out to be the right decision.

Columbia was a graduate school for grown-ups. There were many students just like me, who had been in the world of work, and there were professors who understood that when students returned to school after years in “real life,” the curriculum had to accommodate them. At Columbia, professors seldom required routine papers and tests. Students were expected to do their course work and, when ready, to present themselves for exams, written and oral. This atmosphere led to an urban legend about the English and Comparative Literature Department, of the student who had just finished his fifteenth year and still believed he didn’t know enough to answer questions on the two-hour oral exam that was the prelude to writing a dissertation. I had an entirely different attitude: The Danforth GFW gave its women three years from start to finish and supported a fourth year only under extraordinary circumstances. Relating this fact to my classmates, I said that if I could not manage to bullshit my way through two hours of chattering about literature, I did not deserve the degree.

And so I set myself to it. I began by concentrating on medieval studies for two reasons: because I wanted the deep background and because I thought I needed to prove that I could do “hard work.” Reading novels had been “fun,” but now it was time for “real” scholarship. Still, I found myself constantly drawn to the novelists of the twentieth century and Irish writers in particular. I grew up with parents who were both serious readers and who established an impressive home library and encouraged regular visits to the local public one. They belonged to several book clubs and were devoted to contemporary literature. Joyce had been my lodestone since I first read Ulysses in high school and was barely able to comprehend such an astonishing novel. I read it again as an undergraduate, and at Columbia I devoted my year-long master’s thesis to a single chapter (17, “Ithaca”). Studying Joyce led to immersion in Irish culture, in everything from history and politics to landscape and real people. Thus Joyce led naturally to Beckett, whose fiction I read with more of the same astonishment. But no matter how compelling modern literature was, I still thought of it as something I read for pleasure, and I had the misguided notion that if I were to become a professor, I would have to “work.” And work meant medieval studies, which for me meant plodding slowly through Anglo-Saxon and Latin. I started on a dissertation about garden symbols that required a thorough understanding of medieval Latin because a central text was Saint Bernard’s Sermons on the Song of Songs. As I recall, there were eighty-six and at that time none had been translated from Latin into English.

I began to read them in February 1970, huddled in a cubicle in Butler Library, bundled in coat, hat, and gloves, sure that my breath was freezing on my upper lip and icicles were forming on my eyelashes. I was still reading them in that same cubicle in the sweltering heat of July when I realized how many months had passed and I was only on Sermon 11. At that rate, I envisioned myself as a stooped, white-haired old lady in a pilled sweater and coke-bottle glasses and still a graduate student. The Danforth Foundation had given me three years, maybe four, and I knew I had to find a different subject—and fast—or I would never meet my funding cutoff date. Thus I made a life-changing decision that was based not on aesthetic concerns but rather on one that was financially practical.

I used three-by-five note cards in those precomputer days, and I took a pile of blank ones and fanned them across the desk as if they were playing cards, which in a sense they were. On each one I wrote the name of a contemporary writer whose work I admired enough to want to write about it. As a journalist, I knew how to write fast when on deadline, and if I could define a topic that required no waiting for libraries to find crumbling old books and manuscripts and no ancient languages, I could pull together one hundred or so pages in a year’s time. Joyce, Yeats, Woolf, Conrad, Beckett—I forget who else, but there were just under a dozen names on the little cards. Without thinking about which name might present the best opportunity for original research, or even which I liked the most, I shuffled them into alphabetical order. There were no A’s, and Beckett came first, before Joseph Conrad and E.M. Forster. Beckett it shall be, I said to myself, and that was how my life in biography began.

Like a dutiful beginning academic (powerless and lacking authority), I decided at first to follow the rules and write a dissertation about Beckett that was based primarily on literary theory. I entered the academic world in the waning days of the New Criticism and the heyday of what has since been jumbled together under the broad title of “French critical theory.” The only valid interpretation of literature came from the work itself, not from the author’s life or the world in which he lived (“he” being the pronoun of choice, because the accepted canon then was composed almost entirely of male writers). Never mind that a work might have been produced in haste by a writer who could not pay his rent or take his sick child to a doctor, or by a political ideologue who was writing in fury about his country’s regressive government, or by a frustrated person who had to live a deeply closeted life and could only hint at sexual preference in carefully guarded references. None of this mattered then; only the text itself was relevant.

I remember a little ditty coined during those days that I read in The New York Review of Books, one that perfectly captured the zeitgeist: “This is the story of Jacques Derrida; there ain’t no writer, there ain’t no reader either.” The “holy trinity” of Barthes, Lacan, and Derrida ruled, and there was no place in such an environment for anyone who considered them, as I did, convincing in the main but still unholy. Reading Beckett’s work made me want answers to a lot of questions, all of which were based on the life from which the work sprang rather than from any theorizing of my own or others. And as I wrote, my thoughts called me back to my days as a journalist who knew the tingle that came from identifying a good story.

I was initially attracted to Beckett’s fiction rather than his plays, and in his novels I found many fond and loving references to actual places in the Wicklow Hills and the countryside surrounding his family’s suburban home in Foxrock. Besides recognizing real places, I wondered why others did not see the wit and humor in his descriptions of the thinly disguised Dublin characters who peopled his novels. There were times when I literally laughed out loud as I read his prose descriptions of their real-life antics. I wondered why other scholars and critics didn’t see these aspects of his writing. Were they so intimidated by the political correctness of literary theory that they had no room for real life? Or was I reading his novels with a warped sensibility, particularly as it might have reflected my own skewed sense of humor? I decided to keep an open mind while I read, one that would allow me to decipher his intentions and not impose my interpretations on them. As I listed the questions I wanted the dissertation to answer, I realized that, in short, they were all one and the same: who was the man whose imagination had managed to puzzle and perplex an international coterie of readers, leaving them to wonder about the novels they read and the plays they saw?

I came to realize that I still revered the writer and the creative process; I embraced my status as the renegade student who had the temerity to ask how a literary work came into being, what had inspired it, and who had been the shaping intelligence behind it. “All you need is the when and where,” said the skeptical Professor Unterecker, who knew of my background in journalism and was the only one to whom I confided my “aberrant” interests. He warned me that even to think of investigating such issues in the work of Samuel Beckett would be akin to committing academic suicide. If I wrote what amounted to a biography, he said, I would never get the PhD, never mind a teaching job. At that point I was not sure I wanted one, so I forged ahead.

Unterecker reluctantly agreed to advise the dissertation after I assured him that I was planning to demonstrate sound critical analysis of new and never-before-known information I had collected about Beckett’s writing. But I may have been a touch disingenuous when I told him I would tailor my essay to emphasize theory and stressed that it was merely the foundation for a future in-depth study that could become the all-important first book a scholar needs for tenure. In reality I had no intention of writing such a book. The answers to my questions about Beckett’s work could be found only by looking at the writer who created them, and the only way to do that was through an extended profile or—heaven forfend in the academic world of the 1970s—a biography. (I did admit that the dissertation would have some biographical underpinnings, but they would be so slight that the evaluating committee would have to agree they were there just to provide a basis for my theoretical conclusions.)

Professional considerations aside, this was a challenging proposition. Not only had I never considered writing biography before, but with the exception of some of the classics, I had never read them. On my own as an undergraduate, I discovered and admired Suetonius, Plutarch, and Vasari, and I chuckled over Charlemagne’s two biographers, Notker and Einhard. In graduate school I read the icons, Boswell and Johnson, whom I found delightful but not particularly important as models for my own critical writing. I made the obligatory glance at Froude’s Carlyle and Lockhart’s Walter Scott, but only long enough to agree with various professors who espoused the theory that they were not important for any significant understanding of their subjects’ writings. Even as I enjoyed Lytton Strachey’s scathing Eminent Victorians, I struggled to shake off the theorists who advised students not to mistake any of these “lives” for serious scholarship. They were to be enjoyed in passing, as little more than gossip, for as one professor told me in a statement I would hear all too frequently in years to come, “It’s not scholarship; it’s only biography.”

Meanwhile I wrote the dissertation and was about to get the degree in record time, in spring 1972. I didn’t find a teaching job right away because there were very few in the 1970s, and despite the Danforth Foundation’s entreaties that they should be given to women, those that were available usually went to men. I made desultory applications to some of the colleges in Connecticut and nearby New York, but nothing full-time materialized, and I wasn’t interested in tying myself down to teach an overload of composition courses on a part-time basis for a pittance of a salary. As my dissertation bubbled away in my mind, I realized that I had had so many fascinating experiences and encounters while writing it that I was more determined than ever to write a biography about Samuel Beckett’s life and work.

During this period I often thought of John Unterecker shaking his head, warning about “academic suicide” and how I would “never get a teaching job.” For five years he would be proven right, but neither of us knew it at the time, and one of us really didn’t care.

3

Like Scarlett O’Hara, who always put off worrying about things until the time came to do so, I planned not to worry about getting a job, because first I had Beckett’s biography to consider. When Jack Unterecker (once I had the degree we became friends on a first-name basis) asked how I planned to begin, I replied blithely that I would probably model it after a newspaper profile. Jack had an extremely droll way of speaking and an equally dry sense of humor. He raised one skeptical eyebrow and said, “Don’t you think that before you do anything, you should tell Beckett about it?” As I knew nothing about how biographies got themselves written, and as I was basing my decision on how journalism profiles came into being, it had never occurred to me that I might need “permission,” or an “agreement,” or even a “legal contract”—all expressions I heard for the first time when Jack spoke of them. Undeterred and blithely confident that I already had the necessary skill set, I said yes, of course, and wrote a letter to Beckett.

Once I started to write it, I realized how persuasive it had to be, and I agonized over it as I discarded enough drafts to overflow a wastebasket. In the end, the one I mailed in that hot July of 1971 was fairly brief, written in haste, and taken directly to the post office before I lost my nerve. I didn’t keep a carbon, and after I sent it off, I feared that I had probably portrayed myself foolishly, like a literary Joan of Arc, clad in shining armor and clutching my reporter’s notebook as I rode in to save the day. I do remember writing to Beckett that a biography was a necessary addition to all the critical writing about him, because I read his novels very differently from most other scholars, and I found so much vitality and humor in his prose and such deadly accuracy in his depictions of people and descriptions of places. I must have come off as extremely pompous in that impassioned paragraph, which I hoped would persuade him of the importance of my argument. I concluded the letter with a brief, to-the-point description of myself: a woman who had married young, had two school-age children, and was a journalist and reporter at heart. I asked for the favor of a reply because I did not want to write such a book without his cooperation.

The mail between New Haven and Paris was probably never again as swift as it was during that exchange. A week to the day after I mailed my letter, I received his reply. He began by telling me that his life was “dull and without interest” and “the professors know more about it than I do.” He wrote all that in a tiny, careful, and meticulous hand, on tissue-thin unlined paper, with his writing proceeding in a straight line from left to right. Then came a curious second paragraph, in a larger hand and a scrawl that began at bottom left and rose to top right in several unpunctuated lines: “Any biographical information I possess is at your disposal if you come to Paris I will see you.”

I couldn’t believe my eyes. I kept rubbing the paper, thinking it would say something quite different if I just blinked for a moment. I looked out the window and saw my neighbor across the street, the writer-professor Ernest Lockridge, and I rushed out, waving the letter at him. He was teaching at Yale then, and while I had been studying for my dissertation oral exam, he used to sing a little ditty to the tune of the Miss America song whenever he saw me: “There she goes—think of all the crap she knows.” He had been a cheerful and encouraging voice of reason during my student years, giving me a necessary nudge not to give up whenever I was down. I showed him Beckett’s letter to make sure its content was real, and he assured me that it was. When my husband came home that night, he did the same. A practical man, he said I should call the Danforth Foundation, tell them of this extraordinary invitation, and ask for a special grant to go to Paris. The exceptional woman who ran the GFW program, Mary Brucker, listened as I blurted out my request and said so quietly that I almost didn’t hear, “Of course you must go. We’ll send you the check.”

It was early August when I replied to Beckett to say that I could come in October or November, and he agreed that either month would be fine. My Columbia classmate Nancy MacKnight was planning to spend several days in Paris before going to London for her own research, so we arranged to travel together. At the same time, another Columbia classmate played a major role in helping me get started on the undertaking that would become the biography. Nancy Milford had just bucked the antibiography attitude at Columbia by publishing to great success her groundbreaking feminist study of Zelda Fitzgerald. We were having lunch one day when Nancy asked if I had found a teaching job. I didn’t want one, I replied, because I was going to Paris to meet Samuel Beckett and write his biography.

Several days later, when I was sitting at my desk trying to figure out how biographies are written, never mind how to undertake the many household things I had to do to prepare my family for my absence, my phone rang. A man identified himself as Carl Brandt, Nancy Milford’s literary agent. Nancy had relayed my news, and Carl Brandt told me that if it was true, it would be an astonishing coup in the literary world; he was sure he could arrange a book contract and would like to represent me. I knew that his father had founded the highly respected literary agency Brandt & Brandt, so I was thrilled to join their list of distinguished writers and accepted at once. I could hardly believe all my good luck.

Thus, happily situated with the Danforth Foundation guaranteeing travel money for my initial meeting with Beckett and Carl Brandt holding out the possibility of a book contract and an advance against royalties, I was truly on my way. When I tell this story today, other writers shake their heads in wonder at how easily a new career fell into my lap. They are not alone, for as I reflect back upon my amazing good fortune, I marvel at the ease of it myself.

I was wildly excited when I told Jack Unterecker about all the amazing things that were happening, and he remained his usual calm and tranquil self as he listened. He was also practical: if I intended to pursue such madness, he said, I should go to Dublin and London as well as Paris, and he would provide me with a list of the names of his friends who were also friends of Beckett. Jack had already demonstrated how invaluable such connections could be by introducing me to two New Yorkers who were his close friends and even closer friends of Beckett, the actor Jack MacGowran and the poet George Reavey. Both had enriched my academic work as I finished the dissertation, and now that a proper biography was in the works they were eager to contribute even further. Conversations with them would grant my first insights into Beckett the man rather than Beckett the author. And the letters and other documents they could share would be invaluable.

During Beckett’s unhappy London years in the 1930s, George Reavey was the friend who was determined to help him get his novel Murphy published and who took it upon himself to be Beckett’s agent. Their correspondence covered the years of rejections from forty-two publishers before George finally succeeded in persuading Routledge to bring out the book in 1938. During those frustrating years, as rejections mounted, Beckett wrote letters both amusing and scathing. One I particularly liked was the limerick he composed after a rejection by the American publisher Double-day, Doran: “Oh Doubleday Doran/More oxy than moron/you’ve a mind like a whore on/the way to Bundoran.” When I used this letter in my dissertation, it was one of the earliest indications I had of how Beckett used his withering sense of humor to respond to adversity.

I first met George at his apartment in a tenement walk-up on East Eighty-Fifth Street where he lived with his playwright wife, Jean. It was truly the home of a hoarder, a railroad flat so cluttered that almost all the space was unusable. There were ceiling-high boxes of papers, stacks of books, paintings by his ex-wife, Irene Rice Pereira, and the works of his artist friends (and Beckett’s) Bram and Geer van Velde. There was one narrow pathway down the hallway leading from the entry to the front room, where the only uncluttered space was the sofa that became their bed at night. I could not believe my eyes the first time I walked in, but almost before I could adjust to the gloom caused by all the boxes blocking the dirty windows, George said we should repair down the street to Dorrian’s Red Hand, where we could get a drink. What he meant, as I had ample opportunity to learn from that day on, was that he would drink scotch whiskey and I would pay for it. George was a falling-down drunk, an alcoholic who shrewdly dangled just enough documents to keep me coming back. But every time I became so frustrated over how much whiskey I had to buy that I threatened to have no further dealings with him, I stopped to tell myself that his contributions were priceless. The difficulty was getting him to dole them out, a nightmare that lasted throughout the seven years it took to write the book.

Whiskey drinking was a theme among Beckett’s friends, as I discovered when I met Jack MacGowran in July. He was performing a one-man show at the Lenox Arts Center’s Music Tent in Lenox, Massachusetts. Armed with Unterecker’s introduction, my husband and I drove up to see the pastiche of Beckett’s fictional characters that MacGowran had written for himself. It was an unseasonably cold and rainy night, so windy that the metal chains securing the tent cloth to the poles clanked eerily, enhancing the sound of the shuffling, sniffling MacGowran as he brought life to the characters from Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable. He wore a grungy overcoat several sizes too large, which dwarfed his small, thin frame, and his wretched boots, also too large, flapped loudly each time he took a step, adding another counterpoint to the wind and rain.

The audience howled with laughter when MacGowran performed the sixteen sucking stones episode from Molloy. Things grew quiet as he performed some of the darker passages from Malone Dies, and by the time he got to the last lines of The Unnamable,the audience was hushed in a mix of reverence and agony over the character’s plight. When he said, “I can’t go on. I’ll go on,” the memorable lines from The Unnamable that ended his performance, the only sound in the tent was the occasional clang of a chain until the audience caught enough of its collective breath to surround MacGowran with tumultuous applause. It remains to this day one of my most moving theatrical experiences.

Afterward I went to the tiny dressing room next to the tent, where MacGowran was taking off his makeup and pouring the first of his many post-performance whiskies. He was on a high, having had a full house and a receptive audience that called him back for repeated curtain calls. Gloria, his wife, popped in long enough to tell me not to rush, as he could take his time to talk at length. That was before she chided him to go easy on the whiskey. She might have been talking to the howling wind, for MacGowran was a dedicated alcoholic who made swift work of the bottle. I was enthralled watching him pour a glass whenever he paused to breathe while he gave me what amounted to a second, private performance. When I asked about when and how he first met Beckett, he launched into one story after another, until he stopped suddenly with a look of surprise on his face. “Do you know,” he said, “I’ve never talked about Sam like this before. I have much to say that I think is important, but before you, no one ever asked.”