Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

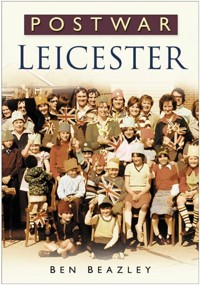

In the thirty years following the end of the Second World War Leicester underwent some of the most dramatic changes in its history. Along with the rest of Britain it saw the austerity of the late 1940s and '50s, the shortages and rationing, followed by the boom period of the '60s, when full employment brought an interlude of prosperity. During these postwar decades sweeping changes were made to the physical structure of Leicester: areas of bomb damage and slum housing were cleared from the old city centre, and an intensive building programme in both the public and private sectors resulted in people moving out to new housing estates on the edges of the city. Ben Beazley vividly describes the story of everyday life in Leicester during this period. Illustrated with more than 120 photographs, maps and plans, Postwar Leicester will capture the imagination of anyone who knows the city today, and will rekindle memories for those who lived through the years of redevelopment and change.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

P O S T W A R

LEICESTER

B E N B E A Z L E Y

The biting winters and heavy snowfalls of the years immediately after the war were enjoyed only by children, such as these seen here leaving Imperial Avenue Infant School. (Courtesy: M. Ford)

First published in 2006 by Sutton Publishing Limited

Reprinted in 2011 by The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

Reprinted 2012

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved © Ben Beazley, 2011, 2013

The right of Ben Beazley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5432 7

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

1.Post-1945

2.Early Recovery: 1947–9

3.Building and Restructuring: 1945–59

4.Slum Clearance

5.Traffic Development Plans

6.Early Postwar Economic Decline: 1945–59

7.The Austere 1950s

8.Acquiring a Civic Centre

9.Economic Decline in the 1960s and 1970s

10.The Smigielski Years

11.The Swinging Sixties: The Early Years

12.The Swinging Sixties: The Later Years

13.The Early 1970s

Postscript

Appendix I

Appendix II

Appendix III

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Without the assistance of almost an army of people who were so generous with their time, materials and knowledge, I would not have been able to complete this book and I would like to express my gratitude to them all.

In particular I would like to thank Carl Bedford for his insights into the early days of the NHS; Margaret Bonney and all of the staff at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland for their help and patience in tracing archival material; Angela Cutting for her assistance in sourcing photographs; John Florance, Stephen Butt and Tony Wadsworth for allowing me access to the Radio Leicester archives and to their own personal material; Tony Green for information on the development of Welford Place; Stuart McGlone for assistance in relation to the early days of BT; Sheila Mileham for her guidance on local authority matters; Sherry Nesbitt for her help on Portal housing; Lionel Roberts for his assistance on civil engineering; Derek Seaton for his encyclopedic knowledge of civic affairs; David Simpson for resolving my queries on military matters; Michael Ward for his accountancy skills; Malcolm Tovey and John Warden for answering my queries on Leicester City Fire Brigade; George Wilson for giving me access to the Leicester City Urban Development Group photograph library, and for his help in understanding planning and development issues.

For allowing me such free access to their personal photograph collections, special thanks must go to Michael Brucciani, Stephen Butt, Colin Chesterman, Geoff Fenn, Margrid Ford, Janice Gunby, Diane James, George Jordan, Inga and Hendrik Raak, Eric Selvidge, E.R. Welford, Margaret and Jan Zientek.

To all of these people, and to any others whom I may have inadvertently missed, I extend my most grateful thanks.

All other pictures are from my own collection.

Ben Beazley

Foreword

Postwar Leicester – what picture do these words conjure up in the minds of residents? Austerity, rationing, utility furniture – a city in monochrome? For those who had come through the Second World War, times continued to be hard in the 1950s, with shortages of food, housing, and jobs, as the traditional industries of the city continued to decline. Even the weather conspired against them, with the harsh winter of 1947/8 still living on in the memory. Yet it was also a time of dramatic change in Leicester, as the city fathers struggled to restore services while beginning reconstruction work. Town planners such as John Beckett in the 1950s and Konrad Smigielski in the 1960s had visionary, if controversial, plans for the city, including some out-of-town estates and remorseless road building which cut a swathe through what had been essentially a medieval town plan. The skyline of Leicester was never to be the same again, as high-rise blocks of flats challenged the dominance of factory chimneys.

But it wasn’t just the appearance of the city that was changing. Leicester’s people became more diverse with immigration into the city on a much larger scale than ever before. During the 1950s, workers from the West Indies came looking for employment, followed by Indians and Pakistanis in particular during the 1960s, then East African Asians in the 1970s, political refugees from the harsh regimes of dictators such as Idi Amin. The complexity of such a diverse population has changed the face of the city, not least in its number of temples and mosques, but also in the vast range of multicultural goods and services which Leicester offers today.

Ben Beazley tackles the fascinating subject of postwar Leicester in this, his latest work. Taking some of the crucial themes of the period, he uses the rich archive of the Leicester Record Office to tell the story of the city during thirty years of rapid change. No one who reads this book could be left in any doubt about the importance of this vital period in Leicester’s history.

Dr Margaret Bonney Assistant Keeper of Archives, Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland

Plan of the Wharf Street District (based on OS: 1930) which was the subject of the Leicester City Council’s first major postwar slum clearance scheme.

CHAPTER ONE

Post-1945

When the Second World War finally ended in September 1945 with the surrender of the Japanese forces, Britain began the long climb back to the rebuilding of its war-damaged economy. In this rehabilitation process, Leicester was, to a degree, one of the more fortunate cities. While enduring the same wartime conditions and shortages as everyone else who had been involved in maintaining the Home Front during the previous six years, crucially, Leicester emerged from the conflict with the greater part of its manufacturing capability virtually intact.

Although the city was subjected to eight air raids during the period of the blitz between 1940 and 1941, only one raid – on the night of 19/20 November 1940 – caused extensive damage. This was to be a significant factor for both Leicester’s immediate postwar recovery and the town’s subsequent industrial potential.

As early as 1944 a Leicester Reconstruction Committee was formed under the chairmanship of Charles Keene – an indefatigable member of the City Council who, having played a key role in the organisation of the city’s war effort, was the ideal person to initiate the local authority’s postwar redevelopment plans. Central to postwar development was the ‘Fifty Year Plan’ developed by the City Surveyor, John Leslie Beckett, which included new housing estates and the restructuring of the city’s main roads. The old-fashioned tramcar system was to be replaced at an early stage by motorised buses, and ten months after the end of the war, in July 1946, sixty-two new double-decker buses costing £3,400 each were ordered by the City Transport Department. Five months later, in December 1946, came the first tram route closure, that of the Aylestone section, in favour of a dedicated bus service.

In January 1946 the Chief Constable, Oswald Cole, set out on a three-month tour of the Middle and Far East as part of a delegation sent by the government to recruit for Britain’s police forces from among the ranks of servicemen awaiting demobilisation. The mission ran into difficulties in the early stages when Cole’s companions (two other chief constables) succumbed to illness and had to return home, leaving Cole to complete the greater part of the trip alone. After interviewing over 1,200 servicemen in locations as far apart as Karachi, Batavia and Singapore he returned home on 13 May, having recruited just over 500 men for police forces (including Leicester City) across the country.

On a broader level, Clement Attlee’s newly elected Labour government was determined to create improved living conditions for the average citizen.

As soon as possible, the school leaving age was to go up from 14 to 15, with the intention that it would eventually be 16. The Beveridge Report, published in November 1942, outlined the government’s vision of a new Welfare State in which everyone, from richest to poorest, would be treated equally. As early as May 1943 the City Council, anticipating the implementation of the Report, adopted some of its provisions, one being that for the first time certain Council employees would be entitled to receive up to four weeks’ sickness benefit during any twelve-month period. Not all of the councillors were in agreement with this concession. Speaking against it, Councillor Percy Russell made the point that, ‘if a man was going to get the same money when he was away sick as when he was well, there would be a great temptation to malinger’. The intention of the government was clear, however – to create a healthier, wealthier and better educated nation.

The city centre was badly damaged by German bombers on the night of 19/20 November 1940. In postwar years, while awaiting reconstruction, many of the sites were used as car parks. Seen here on a rainy day (the police officers are being marched out to their beats from Charles Street Police Station) it presents a gloomy aspect and shows the scale of the work needing to be done. (Courtesy: Leicestershire Constabulary)

Although less well known than Konrad Smigielski, John Leslie Beckett, Leicester city’s Engineer and Surveyor (1941–64), was responsible for preparing a ‘Fifty Year Plan’ at the end of the war for the reshaping of Leicester. Beckett began his working life with Liverpool Corporation in 1918. In 1927 he moved for a short time to be Surveyor and Water Engineer at Runcorn, until in 1930 he became Borough Engineer and Planning Officer of Tynemouth in Northumbria. From 1936 until he came to Leicester in 1941, he worked as the Borough Engineer and Planning Officer at Burnley. John Beckett retired in 1964. (Courtesy: The Municipal Journal)

During the war the ranks of services such as the fire brigades and police were depleted by men and women going into the armed forces. In order to address this, in January 1946 the Chief Constable of Leicester City Police, Oswald John Buxton Cole, went as part of a government initiative on a three-month recruiting tour to the Middle and Far East. Having interviewed over 1,200 servicemen, he succeeded in recruiting 500 for the various United Kingdom police forces including Leicester City Police. (Courtesy: Leicestershire Constabulary)

In the immediate postwar years many firms such as Gimson’s, the town’s leading timber merchants, were still using a combination of motorised and horse-drawn transport. (The tri-wheeled vehicles are Scammells.) (Courtesy: G. Fenn)

Four months after the war ended, enrolling fifty-four women students on a two- year course, the first new teacher training college in the country opened in the old Civil Defence Depot at Humberstone. In the same month the management committee of the Leicester Royal Infirmary purchased Brookfield, London Road, from the Leicester Diocese (it had been the residence of the Bishop of Leicester from 1927 to 1940, when it was taken over and used by the British Red Cross as a packaging centre for parcels being sent to British POWs) and it became the Charles Frears School of Nursing.

In preparation for the increased demands of the new Education Act (a higher school-leaving age meant that there would be an increase in pupil numbers) the now redundant Civil Defence depots at Humberstone, Western Park and Wigston Lane were transferred to the Education Committee. It was also decided that supplementary prefabricated buildings should be erected at Harrison Road, Bridge Road, Moat Road and Melbourne Road schools. The changes in the education system played havoc with the Leicester Education Committee’s 1945–6 budget, resulting in an application for an increase of £76,528 over the previous year, bringing it up to £656,913. Of this increase, 80 per cent was directly attributable to the new Act. Additionally, the Education Committee was obliged to ask for a further £141,515 that year to cover an increase in teachers’ pay scales – a sum that, the Committee were at pains to point out, only covered the pay of teachers presently employed by the authority, and not the staffing increases that would result from the increased school-leaving age.

In the post-1945 era one of the highlights of the working year for those employed by a company was the ‘annual outing’. Seen here on what was probably the first such trip after the end of the war is the workforce of Gimson’s on a day trip to Skegness. (Courtesy: G. Fenn)

Despite the war having ended, foodstuffs and raw materials were still in extremely short supply, and were to remain so for some years to come. Paradoxically, the cost to Britain of winning the war was almost as great as that to Germany of losing it. The Lend-Lease Act which, since 1941, had allowed America to supply material to Britain and ‘other countries upon which the United States’ own defence was thought to depend’, was officially due to come to an end in August 1945. Out of a total of $51 billion worth of aid given by America to its allies, Britain owed a staggering $31 billion. In view of the state of the British economy it was agreed that this should be reduced to an eventual repayment of $650 million. In February 1946 the Minister of Food, Sir Ben Smith, issued a stark warning that when the remaining supplies under the Lend-Lease Act came to an end, food, including dried eggs (which in 1946 alone cost £25 million) and cereals, would have to be imported from the US, and other countries.

In an effort to offset shortages, foodstuffs from the Commonwealth countries began to appear in Leicester shops. At the beginning of March 1946 the first consignment of bananas seen in the city for six years arrived at Leicester market from Jamaica; by the middle of the summer England had received from Canada and Australia 140 million bushels of wheat and flour, 22.5 million pounds of bacon, and over half a million pounds of lamb and mutton; additionally 15 million tins of kippered herrings arrived from Norway. A ‘Leicester League of Housewives’, formed in February, sent letters of protest to the Ministry of Food questioning the need for continued rationing. Their efforts, not unexpectedly, were of little avail, and the league was short-lived. Ironically, a new difficulty presented itself at this stage. While countries such as Canada and Australia were in a position to alleviate Britain’s food shortages, there was not the shipping, storage and distribution infrastructure to deal with the goods. The British government was obliged to decline an offer of 7,500 tons of meat from Australia because, ‘it could not be handled under the present meat ration system’, and 2 million cases of apples were similarly refused because of the lack of refrigerated storage. A million cases of fresh eggs and quantities of butter, margarine and tinned goods could not be imported because there were no ships to freight them.

Rationing and shortages were to continue until 1954. In 1946 a tin of dried eggs cost 1s 6d; milk was rationed to 3 pints per person a week, and adults were allowed 9oz of bread a day (manual workers 15oz).

One area in which it was possible to ease the restrictions early on was clothing and shoes. From the middle of March 1946 constraints on clothing styles were lifted. Dresses with pleats, pockets and velvet trimmings were once more available in Lewiss’s and other department stores. The number of coupons required for clothing purchases was reduced by a third and men’s, boys’ and women’s raincoats could once more be double-breasted, with pockets, buttons and shoulder straps. In a city where one of the main industries was the manufacture of shoes, after April the lifting of the ban on high heels, sandals, brogues and sports shoes resulted in a boom in footwear sales.

In the early summer of 1946 the Ministry of Labour Training Centre (opened before the war in 1936) introduced courses for 600 ex-servicemen to qualify as draughtsmen, bricklayers, carpenters, tailors, typewriter mechanics and radio engineers. A ‘Reinstatement Officer’ was appointed by the Corporation to deal with the issues presented by the 2,000 Council employees now returning to resume their old jobs – among them teachers, policemen and transport workers (by March 1946, of the wartime staff only two female bus drivers remained in the employment of the City Transport Department).

The return of ex-servicemen to their previous occupations occasionally caused certain slightly bizarre situations. One such was the return to duties of Police Constable 77 John Cassie. PC Cassie joined the Leicester City Police in 1937; at the outbreak of the war he served first in the Scots Guards and later was commissioned into the 2/5th Battalion of the Leicestershire Regiment. Six years later he had seen a great deal of action, been awarded the Military Cross for gallantry at the Battle of Monte Cassino in Italy, and as a major was second-in-command of the battalion. (At one point, when the CO was killed, Cassie took command with the rank of acting colonel). When he returned to police duties in April 1946 it was common to see men who had served under him in the Tigers Regiment, on passing the ex-Major working point duty at the Clock Tower, to snap smartly to attention and salute him as they crossed the road.

Accustomed as they were to the vicissitudes of living in postwar Britain, the nation was not prepared for the hardships inflicted by the winter of 1946/7. It was the coldest in living memory, and fifty years on was still clearly remembered by those who lived through it.

Initial indications that Leicester was in for a hard winter came during the first week of 1947, when on Monday 6 January heavy snow began to fall on the city. Within two days a contingent of 250 men and 30 vehicles was busy clearing the streets. This in itself was not unusual, the seasons at that time were generally quite predictable. Leicester was accustomed to hot summers punctuated by heavy thunderstorms and flash flooding, followed by cold, sharp winters and a white Christmas and the 2in fall of snow cloaking the city streets was not seen as anything unusual. For those who had taken notice, however, the previous summer had been one of the poorest for years, the August holiday period being exceptionally wet.

Three weeks later conditions were beginning to give cause for concern. The night of 28 January was the coldest for sixty years, with a temperature of -32°F recorded at Moreton-in-the-Marsh in the Cotswolds. In the East Midlands and East Anglia trains with snow ploughs were out clearing the LMS and LNER lines; the River Thames was frozen over, as was the sea at Folkestone; at Falmouth the temperature was the lowest recorded since 1877.

Experiencing the coldest nights for two years (temperatures recorded at the Towers Hospital showed -19°F below freezing) Leicester emergency squads assisted by a contingent of 200 German POWs were employed trying to clear the city streets of snow and ice in order that the Transport Department could maintain a limited service. Eight water mains burst in the city in two days and the electricity supply was severely disrupted.

Snow very quickly closed all of the county’s roads, isolating outlying villages. Ice building up on the Grand Union Canal at Husbands Bosworth prevented the movement of barges, and rising water levels burst the nearby culvert, causing a loss of 2 million gallons of water. With blizzards sweeping the Midlands, a military convoy of tank transports had to be laid up in the Square at Market Harborough. One of the column’s two low-loaders with a Sherman on board made an abortive attempt to plough a path to Leicester along the A6. Skidding off the road at Kibworth Beauchamp, it had to be dug out by a working party of German POWs from the nearby Farndon Road camp. More POWs were kept busy clearing the drifts that had closed the A47 at Tilton-on-the-Hill.

On Monday 3 February the full implications for the city of the arctic conditions became apparent when, with coal stocks at a minimum and mining work shut down, the first three Leicester factories closed, unable to fire their boilers. By the end of the week many others were forced to follow suit. Some 5,000 building workers were laid off in the city and county; 300 men were idle on the City Council’s New Parks housing estate project. The closure of the Leicester Brick and Tile Co.’s yards, with the consequent loss of 250,000 bricks a day effectively stopped work on twenty building sites across the city.

Food supplies in Leicester market dwindled rapidly. Vegetables could not be lifted from the frozen earth, and with road and rail links blocked, such produce as was available could not be delivered. Attendance dropped by 40 per cent in those city schools that managed to stay open.

By the second week in February 80,000 factory workers in the city (over half of the workforce) were laid off; 18,000 of the temporary signings at the Labour Exchange were from hosiery factories. All of the shoe factories (with the exception of a few that generated their own power) were forced to shut down, resulting in the loss of between 3,000 and 4,000 pairs of shoes a week at a cost to the industry of £250,000.

Engineering firms also suffered. By the end of the week the British United Shoe Machinery factory had been reduced to 20 per cent of its capability. The closure of 1,200 factories in Leicester during the first two weeks of February, with the attendant loss in earnings, cost the city £3 million. On Saturday 15 February a special ‘signing-on’ centre was opened at the Granby Halls and at the end of the day figures showed that 20,000 men and women in the city were temporarily in receipt of benefits. Projections were that by the end of the following week the figure would exceed 50,000. Wherever possible workers were employed by factory managers on maintenance work and painting, but this had little effect on the overall figures.

Leicester was not alone in its situation; around three-quarters of the country was similarly affected. Due to the shortages of fuel, the City Council agreed to make some of its stocks of coke available for domestic use. During the morning of Saturday 15 February, when the supplies were allocated, a queue of never less than 500 people was to be seen outside the Aylestone Road Gas Works from 7 a.m., when it opened, until the gates closed at noon.

City-centre shops, while being encouraged to remain open for as long as possible, were prohibited from using any form of heating. Cinemas no longer held matinée performances and City Transport was running only 20 per cent of its normal services. In an attempt to regulate the supply the Electricity Department initiated phased power cuts, and street lighting was reduced to one electric lamp in every three. Later, as these conditions continued, the supply of electricity was ‘zoned’, and districts received power on a rota basis at different times of the day.

Working in extreme conditions, towards the end of the second week in February the Leicestershire pits eventually managed to reopen and began a limited clearance of their yards. By close of work on Friday of that week 4,000 tons of coal had been dispatched by road. Over the weekend, using POWs, the railway line between Coalville and Leicester was reopened, allowing a further 3,000 tons to be moved.

As the third week in February began, conditions worsened. Temperatures remained constantly below freezing, the Channel ports were blocked by ice, and fishing was suspended. Royal Air Force planes patrolled the North Sea searching for icebergs, following the appearance off the East Coast near to Lowestoft of an ice floe 4 miles long by 1⁄2 mile wide.

By a combination of the zoned electricity supply and employers arranging for factories to work staggered hours (single or two-shift working), production in Leicester slowly began to come back on line. During the third week of February coal supplies – reduced by 70 per cent and restricted to industrial use – began to trickle back into the town. Already the City Council was beginning to count the cost. In addition to the loss by the private sector of industrial production due to almost continuous snowfall, 500 men were now employed on a 24-hour rota dealing with snow clearance alone; 783 tons of sand and gravel had been spread over the city streets, and the conditions showed no signs of abating. After more than a month of snow the blizzards were still continuing, and such rail traffic as there was in the district was being used exclusively for the movement of coal supplies. The number of temporarily unemployed in the city had reached 54,000 and there were now concerns as to whether or not the supply of domestic gas could be maintained.

Sunday night, 23 February, was one of the coldest ever experienced in the county. Thirty-five degrees of frost were recorded at Woodhouse Eaves, and 23 degrees at the Towers Hospital. (Nationally, temperatures were the lowest since the winter of 1917). Trains at London Road and Great Central railway stations were at a standstill, unable to move because, not only were the points frozen solid but also, despite fires lit under them, the water columns (tanks used to supply water to the boilers of the locomotives) had turned to ice.

The change in the weather, when it finally came, was sudden. The first signs of a thaw began in Leicester on 25 February (although some of the worst blizzards of the emergency were still sweeping the north of England). Temperatures at the Jarvis Street Depot suddenly lifted to 43°F, the warmest for thirty-eight days.

Inevitably, the change in the weather conditions brought further problems. The Water Department dealt with 120 burst water pipes in one day (since the beginning of January it had already repaired 2,516) and the City Gas Department received 700 reports of frozen gas pipes. Garages across the city were inundated with motorists who, trying to start their vehicles, found that radiators and engine blocks, frozen solid for a month, were now cracked and useless.

Although the worst of the weather was now over, conditions still gave considerable cause for concern. Heavy snowfalls continued and firemen from Lancaster Place struggled to thaw out the eighty underground water tanks situated across the city. At the end of the month the cost to the Corporation of snow clearance alone stood at £15,000 – 450 men a day, using 70 to 80 lorries at any given time were still working around the clock. On Saturday 1 March the queue waiting for coke outside the Gas Works began to form at 3 a.m., and by 7 a.m. numbered over 2,000. The thaw brought other dangers. At Blaby two 8-year-old girls, Ann Dorothy David and Patricia Oates, both of Hillsborough Road, were drowned when the ice on which they had played during the last month collapsed beneath them. Throughout the rural districts of the county melting snow and thawing rivers caused widespread flooding.

Improving conditions rapidly resulted in factories reopening and transport returning to some degree of normality. More men than ever were thrown into the clearing-up process throughout the city, and at the end of the first week in March the gangs of workmen numbered over 1,000 strong.

Determined not to be caught out again, during the ensuing summer months the Corporation, aiming to conserve resources, made elaborate projections to stagger working hours in factories during the following winter. (In October 1947 a prohibition was imposed on the heating of factories until after 3 November, and Leicester coal merchants were already pointing out that, on a domestic level, they were unable to supply the government’s recommended six months’ winter allowance of 30cwt per customer, and a maximum of 10cwt for the first three months was as much as they would be able to manage.) It was a clear case of closing the stable door after the horse had bolted, and met with a limited response from both employers and workers. On the one hand the proposals would severely disrupt production, on the other they would drastically affect earnings.

Fortunately for everyone concerned, the winter of 1947/8 was not exceptional, and despite threats from the Board of Trade that punitive action would be taken by the Ministry of Fuel and Power against factory owners who refused to comply with instructions, the proposals were largely allowed to lapse.

It was very apparent that apart from the issues presented by the re-employment of men returning from the forces, the major long-term problem facing Leicester City Council would be that of providing adequate housing.

As a short-term solution plans were made by the Leicester Reconstruction Committee during the initial phase in 1944 for the erection of just under 800 temporary ‘Portal’ houses (named after Lord Portal at the Ministry of Housing), or ‘prefabs’, as they quickly became known, to be erected at various points throughout the suburbs. The first of these began to appear on Hughendon Drive at Aylestone Road in April 1945.

Next, the War Office was persuaded to clear the armoured vehicle park on the north-west side of the city, and with the departure of the last Crusader tank on 27 September 1945 work was begun by German POWs, digging out the roads, drainage and service systems for the New Parks estate, which was to be the Corporation’s postwar showpiece in modern housing. With the first brick laid in January 1946, work on the estate was finally completed in October 1949 when 2,748 houses in varying styles (including 120 prefabs) had been completed. (Blocks of flats along Aikman Avenue were to be added at a later date, with plans being laid in 1950.)

These beginnings were quickly followed in the early postwar months by further proposals. A development scheme for Braunstone estate included a community centre, baths, a health centre, three secondary schools, a Baptist church and two Roman Catholic churches. As time passed further attention was paid to the area when, late in 1949 with the future of Braunstone Aerodrome in the balance, it was suggested that the site was made available for a housing development.

The Scraptoft Valley Development Plan was first considered by the City Council in January 1946, followed by proposals for the building of the Thurnby Lodge and Goodwood estates. In accordance with John Beckett’s ‘Fifty Year Plan’, the question of clearing slum properties from the city centre areas, such as Wharf Street, was examined and time scales were drawn up.

An additional incentive for the provision of housing was the fact that by September 1947, with the improvement in postwar living conditions, the birth rate in Leicester was higher than the national average. The Education Committee estimated that, combined with the raising of the school leaving age to 15, by 1952 an additional 2,400 infant and 6,000 junior places would need to be found in city schools.

October 1947 saw the return to England of the 2nd Battalion Royal Leicestershire Regiment. (A special Army Order, promulgated in December 1946, granted to the regiment the title ‘Royal’.) After nine years’ continuous duty overseas 23 officers and 506 other ranks arrived at Southampton docks from Bombay. Following a leave period of twenty-eight days, they took their first home-based posting at Long Marston near Stratford-upon-Avon, working on clearing up the backlog of stores left by the war.

The following month, the 1st Battalion disembarked at Harwich from Germany, to return to its base at Glen Parva Depot. Its stay was not a long one (it was customary for only one battalion of a regiment’s two regular battalions to remain on home service while the other performed duties overseas); after eighteen months, in May 1949, under Lieutenant Colonel S.D. Field the battalion left for service in Hong Kong. Its stay at Glen Parva was punctuated by a running battle for accommodation. There were only sufficient married quarters for twenty-six families, most of which were already occupied by members of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Royal Army Pay Corps, Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, 8th King’s Irish Hussars (now responsible for the training of armoured units at the Leicester East Airfield) and Records Office personnel.

The sale of clothing, which had been on ration since June 1941, was one of the first things to become derestricted, in March 1946.

On a day-to-day level, the routine of life in the city began slowly to settle down. The wartime National Fire Service (NFS) was about to be dissolved and Leicester was not only to revert to once more having a Leicester City Fire Brigade, the man who had previously been Chief Officer, Errington McKinnell, was to return to his former position at a salary of £1,250 a year.

Applications were being received at a rate of fifty a day for new business and telephone lines to be installed, resulting in the reopening of the old manual telephone exchange in Rutland Street – closed since 1926 when the exchange at Free Lane rendered it temporarily obsolete – under the name ‘Granby’.

In November 1947 the local elections, reflecting the general mood of the country, secured for Labour thirty-five seats on the City Council (giving them twenty-five councillors and ten aldermen). With import duties being eased on commodities such as machine tools, textile machinery, clothing and shoes, the city was set to make the most of having won the war.

CHAPTER TWO

Early Recovery: 1947–9

Not unexpectedly, it took some time and a considerable amount of readjustment for life in the city to recover its peacetime aspect. Men and women who for the last six years had either been away fighting or working at home to keep the factories producing and the economy afloat, now found themselves having to adjust to the changed circumstances of postwar Britain.

Rationing, one of the greatest impositions on domestic life continued into the 1950s. Demobilised service personnel had to be reassimilated into the workplace, the military presence in the city had to be wound down, and six years of Civil Defence provisions put into mothballs.

In December 1946 the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) left Glen Parva Barracks, Wigston, for Queen’s Park Camp at Guildford in Surrey. Queen’s Park, previously a dispersal camp, then took over as the only ATS training unit in the country, leaving Glen Parva vacant for occupation by the returning men of the Leicestershire Regiment.

Similarly, a month or so earlier, in May 1946 a decision was taken by the War Office to transfer the Royal Army Pay Corps from its base in the city to Perham Downs on Salisbury Plain. During the postwar years the RAPC was to have a long if somewhat fragmented association with the city.

Housed since its transfer to Leicester from Warley in 1939 in the old hosiery factory of T.H. Downing at 3 Newarke Street (which was to be transferred to the College of Technology), the RAPC as part of the combined staff of military, ATS and civilians, employed in its two offices at Newarke Street and Great Central Street (along with four other lesser sites) around 1,000 civilians. During the heaviest air raid over the city on the night of 19/20 November 1940 several members of its unit were killed when the house in which they were billeted in Highfields sustained a direct hit from an HE bomb.

In 1946 about 400 of those employed by the RAPC were local people, who became unemployed as a result of the move. Pressure from these civilians resulted in the location of the new offices being changed from Salisbury Plain to Nottingham, with a moving date of 20 October, which gave some of those affected an opportunity to move with the military staff rather than lose their jobs.

The removal was short-lived and in 1948 the Pay Corps returned, taking up residence in the Ministry of Labour Training Centre on Gipsy Lane (the premises had started out life as a nail-making factory). One of the drawbacks of this site was that it had no living accommodation and, other than a few allocations of married quarters at Glen Parva Barracks, all of the warrant officers and NCOs had to be billeted out in private accommodation. After a second spell in Leicester, the RAPC moved again, first in February 1961 to Brighton and Foots Cray, and then in 1963 to Bestwood in Nottinghamshire, before returning to the district in 1977, this time to Glen Parva Barracks. The unit remained at Glen Parva for the next twenty years until its dissolution at the end of March 1997, when it was absorbed into the Army Personnel Centre at Glasgow. Although spasmodic, over a period of almost sixty years the RAPC was a substantial employer in Leicester city.

One unique circumstance that the RAPC in Leicester could claim during its wartime presence in the city was the inclusion among its ranks of one Lieutenant M.E. Clifton-James. Clifton-James was Australian by birth, and bore an uncanny resemblance to Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery. Having been badly gassed during the First World War, he later took to an acting career and was 41 when the Second World War broke out. While he was appearing at a London theatre his similarity to Montgomery was picked up on by Military Intelligence, and he was quietly recruited to be used as a double for the Field Marshal as and when necessary. As a cover he was inducted into the army, given the rank of lieutenant and posted to the RAPC at Leicester. When the film of the subterfuge entitled I Was Monty’s Double, starring Clifton-James alongside John Mills, was produced in 1958, one of the early scenes was shot in the Queens public house on Charles Street. (M.E. Clifton-James died at Worthing in Sussex five years later, in May 1963.)

As part of the process of standing down the armed forces units, various establishments were handed back by the War Office to local authorities, among them the various airfields around the city and county. One such not far from the city was Desford Aerodrome, which, having been used during the war as a repair depot for damaged aircraft and to train bomber and fighter pilots, became a training centre for the RAF Reserve. The airfield returned to civilian status and local men who had previously served as pilots and aircrew were recruited by the Air Ministry. This was very much a reversion to the aerodrome’s pre-war function when it had been used to train RAF Volunteer Reserve pilots (Leicester Aero Club was formed there in 1929), and the aim was to recruit up to 300 men to set up No. 69 RAF Reserve Squadron. In October 1949 the Council’s General Purposes Committee also decided that Braunstone Aerodrome on the city boundary would no longer be used for flying.

The site of Leicester East Aerodrome at Stoughton continued to be used for military purposes, and in February 1948 the 8th King’s Irish Hussars arrived from Germany to take over the airfield as a new training ground for the 9th Armoured Brigade, Territorial Army, where it remained until January 1950. The following year, in June 1949, Ratcliffe Aerodrome came up for auction. With the lease due to expire in March of the following year, its occupants, the Leicester Aero Club, were given first option on the purchase, although from the outset the Chairman of the club, Roy Winn, was doubtful that the offer would be taken up because of financial constraints. As with almost every other airfield across the country, Ratcliffe had served its purpose, in this case being used by ferry pilots (many of whom were women) engaged in flying replacement military aircraft between UK air bases.

Relatively inconsequential items such as the Territorial Army huts on Victoria Park, which still belonged to the War Office, were left in situ until 1950. Bomb-damaged areas in Highfields and around the city centre, were to wait even longer for redevelopment. The Nissen huts erected on Victoria Park at the beginning of the war were demolished in June 1950 by a detachment of Royal Engineers.

A bomb site at the junction of Sparkenhoe and Saxby Streets, which was one of the last to be redeveloped when Highfields Infants School replaced the devastation caused in 1940 by German bombers. (Courtesy: E.R. Welford)

During the war they were occupied initially by a Home Guard Rocket Battery; the next tenants were the ATS, who in turn were succeeded by a unit of the 159 (Independent Armoured Brigade) Royal Army Service Corps (TA) along with a small unit of Military Police. The MPs moved out in May 1950, and when the huts were demolished the Territorials moved to the barracks at Brentwood Road. One of the problems associated with the high wartime levels of military presence in the district was that of live ordnance, which was left around in dumps on the outskirts of the city and in the county. In April 1944 during the Easter school holidays three schoolboys, Lawrence Mann, Alan Dilks and Eric Orton, while playing on an American Forces weapon firing range on the north side of the city, found an unexploded bazooka round which they decided to take home. While they were carrying the round along Fairfax road it exploded, killing Mann and injuring both of his friends, together with three young girls who happened to be standing nearby. During May 1948, three young Leicester men out for a cycle ride in the country stopped to examine an abandoned ammunition dump and were severely burned when a quantity of black powder exploded.

The postwar Labour government of Clement Attlee was dedicated to social and economic changes, bringing in, among other things, the nationalisation of the Bank of England, coal mining, civil aviation, rail and road transport, the steel industry, and above all the setting up of a national health scheme. The introduction in June 1948 of one of the government’s most ambitious postwar initiatives, the National Health Service, had a mixed reception. The public – the prime beneficiaries of the scheme – were, not unexpectedly, elated at being presented with health-care provisions that previously they could only have dreamed of; for the professionals, however, doctors and dentists accustomed to the incomes generated by private practice, the proposals were not so attractive.

In Britain the concept of ‘pre-paid medicine’ was not a new one. A National Health Insurance Scheme had come into being in July 1912 under the Liberal government of David Lloyd George. At a time when all medical services were in the hands of private practitioners, this scheme was based upon individuals’ ability to pay an insurance premium which entitled them to treatment on ‘the panel’ of a participating doctor. Twenty years later, in Great Britain and Northern Ireland 17.2 million people (11,369,000 men and 5,808,000 women) were enrolled on the panels of 16,000 doctors. Over 10,000 chemists’ shops were fulfilling panel patients’ prescriptions. (There were still many medical practitioners not involved in the scheme, who would fill out their own prescriptions at their surgery.) The population of Leicester at this time was just over 239,000 people, of whom 117,000 (49 per cent) were signed on to doctors’ panels. The obvious conclusion to be drawn from this was that the remaining 51 per cent – the most needy, those too poor to pay the insurance premiums – were excluded.

The concept of a postwar national welfare scheme originated in 1941 when Sir William Beveridge was commissioned by the government to conduct an inquiry into the structure of social services in the country. In December 1942 he produced a document entitled Social Insurance and Allied Services, which became known simply as ‘The Beveridge Report’. He proposed that all working adults, in return for a weekly contribution deducted at source from their wage packets, should be entitled to benefits if they were sick, unemployed, retired or widowed. (Under the new measures a man received 10s a week on reaching pensionable age, and on retirement was entitled to an extra 16s; the allowance for uninsured wives was 6s a week.)

The reaction of medical practitioners to Beveridge’s proposals was, not unexpectedly, mixed. In February 1948, following Aneurin Bevan’s declaration that the scheme affecting some 50,000 doctors would be implemented within a few months, the dissent was strong. Nationally, of those polled only 4,084 said ‘Yes’, while 25,310 said ‘No’. The British Medical Association estimated that about 88 per cent of doctors were opposed to the scheme on the basis that it was not viable inasmuch as the government would not be able to put together an infrastructure capable of supporting it. Other underlying considerations were their loss of independence and private incomes. Bevan did a lot of negotiating in an attempt to bring them around. Family doctors would be known as General Practitioners, or GPs; hospital consultants, while being part of the NHS, would be salaried and allowed to continue treating some patients privately. Previously run by local authorities or charitable institutions, 1,143 voluntary and 1,545 municipal hospitals across the country were to be taken over by the government. (The Leicester Royal Infirmary was handed over to the National Health Service by its management committee in June 1948.)

Four weeks before the Health Service went live, doctors in Leicester called an emergency meeting to discuss whether or not to accept the terms of the new Health Service Act. Although the majority were opposed to the changes, they now faced a dilemma. If they stayed out of the NHS and obdurately continued in private practice while an overwhelming proportion of the city’s population enrolled in it, they would be financially worse off. The result was that the National Health Service came into operation on 5 June 1948 and, accepting the inevitable, most practitioners in the city signed up.

There was, not unnaturally, a certain amount of initial confusion regarding the administration of the system. A list of the doctors in Leicester who had signed up to the NHS, which should have been displayed in public libraries, was still not available in the early weeks of July. The general consensus, however, was that ‘panel patients’ would remain with their panel doctor and others with their family doctor. In fact, by the mid-point of July one hundred and eleven doctors in the city had enrolled into the NHS, with local dentists and opticians following suit. Dentists experienced a huge upsurge in demand for their services through the NHS. Dental hygiene had previously been seen as a very low priority; during the First World War a group of Leicester dentists had actually volunteered to remedy (mainly by extracting) the teeth of local recruits to the army before they could be accepted as medically fit. The resulting problem was not that dentists could not cope with the volume of work, but that dental workshops in the town did not have sufficient technicians to produce the huge number of dentures suddenly required.

One important change was the manner in which medicaments were now to be dispensed. As from 5 June 1948, chemists took over responsibility for the dispensing of medicines. Doctors other than those with practices in remote areas where there was no chemist were no longer allowed to fill out their own prescriptions. (An exception to this was where practitioners were going to administer drugs in their own surgery.) The change saw the closing down in Leicester of the dispensaries and Friendly Societies around the town. This affected around 45,000 people who had used the Public Medical Service Central Dispensary in East Street, or the Oddfellows and Foresters dispensaries.

As with any other social development, there were those who found ways to turn the new welfare system to an advantage. Many years later Carl Bedford, who in the early years following the inception of the NHS was a dispensing chemist at Boot’s in Gallowtree Gate, recalled some of the methods enterprising individuals found for exploiting the new pharmaceuticals goldmine. There was an early ‘run’ on surgical dressings, which under the new dispensing arrangements could be obtained free. Chemists were quick to realise, when presented with demands for half a dozen packs at a time, that 1lb rolls of white lint (used to dress leg ulcers, etc.) made excellent bed linen! One pound jars of ‘White and Yellow Soft Paraffin’ or, as it was later branded and marketed, ‘Vaseline’, made an excellent grease for items such as cycles and motorbikes.

From the chemists’ point of view, there was also a slightly bizarre aspect to some of the legitimate prescribing. At a time when commercially produced items were not as readily available as in later years, some strong morphine-based painkilling preparations had to be made up in liquid form by the chemist on the premises. These contained brandy or another similar spirit, and it was not unusual for a junior to be sent out to purchase a bottle of brandy from the nearby Hynard Hughes shop. Storing it securely in the dangerous drugs cabinet, the pharmacist would set it against NHS expenditure.

An unfortunate result of the chicanery generated by the free prescription scheme was the introduction in October 1949 of a 1s charge for each prescription in an attempt to curb the abuses (except for OAPs and War Pensioners) resulting in the vehement protests and eventual resignation from the government of Aneurin Bevan.

In April 1948 the National Fire Service (a wartime measure) was dismantled and brigades returned to their old local status. The former Chief Officer of the Leicester City Brigade, Errington McKinnell, was reappointed to his former position at a salary of £1,250 and rejoined the brigade on 1 May 1948. He remained as Fire Chief until his retirement in February 1964. Seen here in October 1954 he is presenting the prestigious ‘Silver Axe’ award to top recruit Lionel John Warden. Having previously served in the Royal Artillery as a regular soldier in the Far East during the Malayan Emergency, John ‘Stretch’ Warden was himself to become a Senior Fire Officer, retiring as an Assistant Divisional Officer in 1986. (Courtesy: J. Warden)