13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Princess Diana is seen as the first member of the British royal family to tear up the rulebook, and the Duchess of Cambridge is modernising the monarchy in strides. But before them was another who paved the way. Princess Mary was born in 1897. Despite her Victorian beginnings, she strove to make a princess's life meaningful, using her position to help those less fortunate and defying gender conventions in the process. As the only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary, she would live to see not only two of her brothers ascend the throne but also her niece Queen Elizabeth II. She was one of the hardest-working members of the royal family, known for her no-nonsense approach and her determination in the face of adversity. During the First World War she came into her own, launching an appeal to furnish every British troop and sailor with a Christmas gift, and training as a nurse at Great Ormond Street Hospital. From her dedication to the war effort, to her role as the family peacemaker during the Abdication Crisis, Mary was the princess who redefined the title for the modern age. In the first biography in decades, Elisabeth Basford offers a fresh appraisal of Mary's full and fascinating life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

About the Author

Elisabeth Basford is a writer based in South Yorkshire. She has twenty-five years’ experience as a teacher and examiner, and has written for magazines and online publications including Majesty, Red and Goldie. She writes about history, education, the arts, culture and lifestyle on her popular blog Write on Ejaleigh! She has also contributed a chapter on gardening and mental health to What I Do to Get Through, a collection edited by Olivia Sagan and James Withey.

Praise for Princess Mary

‘Filled with never previously known information, this first full biography is the definitive read for this refreshingly forward-looking, eternally good-willed and relatively little-known Princess.’

Annabel Sampson, Tatler

‘She was an exemplar of the unflagging postwar countess, always doing good, always keeping busy to stave off grief. When we contemplate the Queen’s lifelong devotion to duty, we sense the influence of her unpretentious aunt.’

Ysenda Maxtone Graham, The Times

‘Surprisingly, there has never been a biography of Princess Mary, the Queen’s aunt and sister to George VI and the Duke of Windsor, until now. Elisabeth Basford’s diligently researched account of the princess’s life is therefore a welcome one … Basford persuasively argues that she was a thoroughly modern member of the royal family, possessed of genuine compassion and interest in helping others … Perhaps some of her descendants could learn from her.’

Alexander Larman, The Observer

For J.D.

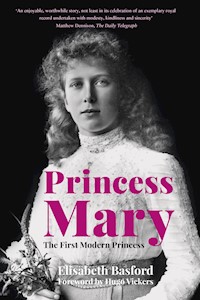

Front cover illustration: Princess Mary c. 1913. (© Alamy)

First published 2021

Reprinted 2021

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Elisabeth Basford, 2021, 2022

The right of Elisabeth Basford to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 700 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Preface

1 The Birth of a Princess

2 Childhood and Education

3 Death of Edward VII and Accession of George V

4 The First World War

5 Nursing

6 The Royal Scots Guards and Other Charitable Patronages

7 The Girl Guides

8 Harry

9 Wedding

10 Honeymoon and Early Married Life

11 Royal Family Life

12 Harewood

13 The Death of George V

14 The Abdication Crisis

15 The Outbreak of the Second World War

16 War Work

17 Prisoner of War

18 Death of Harry

19 George and Gerald

20 Chancellor

21 The Deaths of George VI and Queen Mary

22 A Family Affair

23 Later Years

24 Legacy: A Purposeful Life

Notes and Sources

Acknowledgements

There are many people who made the research and writing of this biography such a joyous experience and to them I am truly grateful. Every effort has been made to locate copyright holders and obtain permission to reproduce sources. For those sources where it has been difficult to trace the copyright holder of the work, I would be grateful for information. If any copyright holder would like an amendment to the acknowledgements, please notify me and I shall gladly update the next reprint. Sincerest apologies if I have omitted anyone from this list. Again, I would be happy to amend this in the next reprint.

My thanks go to the following for providing considerable research material. To Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II for her gracious permission to study and reproduce Princess Mary’s letters and Queen Mary’s letters and diaries. To the Royal Archives at Windsor and especially to Julie Crocker, Lynette Beech and Colin Parish. If it had not been for Colin, I would never have made it up the steep incline to the Archives. To Mark and Clare Oglesby at Goldsborough Hall, who started me off on my journey and gave their time and considerable knowledge so generously. Goldsborough Hall is now as spectacular as it was in the time of Princess Mary and visiting the Hall inspired me greatly. To David Lascelles, 8th Earl of Harewood, and the Harewood House Trust, especially Rebecca Burton and Lindsey Porter for permissions and assistance in all things Harewood. To Tasha Swainston, archivist at the National Army Museum and Elizabeth Ennion-Smith, Pembroke College, University of Cambridge for enabling me to see so many of Mary’s letters and for helping me to disprove another misconception concerning Mary. To Christopher Ussher, Princess Mary’s godson, for personal insight. To the Royal Scots Regimental Office and Frank Gogos, curator at the Royal Newfoundland Regiment Museum for information concerning Mary as a colonel-in-chief. To Jane Rosen and Belinda Haley at the Imperial War Museum for so much information concerning the Princess Mary Tin and enabling me to hear Mary’s voice for the first time. To Lord Middleton for permission to view a large number of letters from Princess Mary to Lord Middleton. To Gareth Williams, curator and head of learning at the Weston Park Foundation for being so generous with his knowledge and for providing many photographs. To Anne Williamson and John Gregory of the Henry Williamson Society for such benevolence. Rebecca Higgins at Special Collections, University of Leeds Library. University of Leeds Archive for sourcing information relating to Mary’s patronage of the university and information regarding her patronages in the north of England. To Denise Summerton and Jayne Amat, Manuscripts and Special Collections, Nottingham University. To Guy Storrs, for permission to reproduce extracts from the Ronald Storrs archive and such a wonderful email correspondence. To L’Institut Pasteur for permissions relating to the Duke of Windsor.

In addition, I should like to thank the institutions who provided contemporary sources and information from their archives: Alan and Julie at the Special Collections Department, Toronto Reference Library; the Australian War Memorial; the Borthwick Institute for Archives, York; Danielle Triggs, West Yorkshire Archive Service, Leeds; Helen Clark, supervisor, East Riding Archives; Library and Archives, Canada; Nick Baldwin at Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; Aidan Haley, assistant archivist and librarian, Devonshire Collection Chatsworth; Lloyd Pocock from Ashstead Pottery; Lyndsey Hendry, Girlguiding UK; Newfoundland Museum; Portumna Castle; Public Record Office Northern Ireland; QARANC Association; Rebecca Jackson, Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Archive Service; Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre; the Memorial University of Newfoundland; Visit Portumna; West Yorkshire Leeds Archives; Ludgrove School.

Thanks to the British Newspaper Archive and in particular Eddie Bundy for permissions and proving to be such an invaluable source of factual information and to Tom at Back Issue Newspapers for providing copies of The Times.

For additional photographs: Bibelots London: Ephemera and Curiosities; the wonderful Barry Sullivan at D.C. Thomson; Royal Newfoundland Regiment Museum; Lee Turnbull; Victoria Ann Fletcher for her incredible image of Harewood.

Individuals who shared with me details of their personal archives so generously: Elaine Merckx at Wakefield Girls’ High School; Joy Broughton at the Red Poll Cattle Society; Julia Knight at the Queen Mother’s Clothing Guild.

For additional permissions: Katie Widdowson, assistant archives officer, UK Parliament, Westminster, London; Kate Symonds at the Wellcome Collection; Laura Lacey, rights and licensing executive, British Medical Journal; Megan McCooley, moving image archivist, Yorkshire Film Archive; Penguin Books; Renegade Productions; Orion Publishing Group; Jack Baker at Harper Collins Publishers; the Jack the Ripper Tour; the Witchita State University Digital Collection; the Girl Guiding movement; the Irish Wolfhound Society; Wakefield Publishing; BBC Sounds; JPI Media; Orion Publishing Group Ltd.

For details concerning personal items belonging to Princess Mary: Christies Auctioneers.

In the virtual world of social media: to all the followers of my blog Write On Ejaleigh, especially Messiah Kaeto. To the Facebook and Instagram followers of Princess Mary, Princess Royal. To Nash Rambler and the Esoteric Curiosa.

To Mary Mackie for her knowledge of PMRANS; Marlene A. Eilers Koenig for her encyclopaedic knowledge of European dynasties and Alexandra Churchill for her knowledge of George V as a father. To Milly Johnson for inspiration in my writing. To Nick Holland, a fellow writer and Brontë lover, who supported and encouraged me right from the very start of this process.

To The History Press, especially Christine McMorris and my editors, Simon Wright and Alex Waite, for helping me to tell Princess Mary’s story.

An immense thank you to the wonderful royal biography community, who have welcomed me so warmly. My sincere thanks go especially to the late Christopher Warwick, who helped me so much during the research and writing process. His death is such an immense loss. He was a kind-hearted and generous friend with an incredible knowledge of royal history.

To my family and friends for understanding during this process, especially to Auntie Jenny for supporting me so much in my writing, William for his historical context knowledge and Sofia for all things social media and IT.

Thank you to Joanne Spick for sparking my love of royal history since 1982 and Derek Maberly for encouraging me to write this for thirty years.

Thank you to Hugo Vickers for kindly writing a foreword and for assisting me so much in my research. For years I have admired you greatly and I am still so much in awe of you.

To my husband, Jonathan. I am so fortunate to have your support in everything and I could never have done this without you.

Finally, this book is dedicated to my dad, who always answered every question I asked as a child, sat around waiting for me at every event, got himself into immense debt to ensure I was educated and more than anything else, encouraged me to write this book. Thank you, J.D.

Elisabeth J. Basford, 2020

Foreword

At last a biography of Princess Mary, the Queen’s aunt – and a good one. Until now, we have had to search for her in other books, perhaps the best account can be found in the memoirs of her son, Lord Harewood – The Tongs and the Bones. She was the daughter of George V and Queen Mary and sister to two kings. She has long deserved a full study and in Elisabeth Basford she has found a dedicated and sympathetic biographer, who has done her full justice.

In the early days of this reign, the Queen and Prince Philip had a young family and there were very few working members of the Royal Family, the others being the Queen Mother, Princess Margaret, the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester, and Princess Marina, with the young Duke of Kent and Princess Alexandra beginning to undertake royal duties. Princess Mary was a hard working member of this team, doing what the Royal Family do best – supporting the monarch and taking on the engagements she doesn’t have time to fulfil. In this book, we see Princess Mary emerging from the confines of royal life as an immensely popular princess, nursing in the First World War, supporting the troops in whatever way she could, and her marriage to Viscount Lascelles, becoming Yorkshire’s Princess – but this did not stop her travelling all over the world. She was well known in Canada and the Caribbean, and 17,000 children cheered her to the echo as she toured a racecourse in Ibadan in an open Land Rover during an important visit to Nigeria in 1957, waving with the circular hand wave of Queen Mary. Princess Mary had to face many challenges in her life and Elisabeth Basford tackles these as well.

It is a particular pleasure for me to be asked to introduce this special book. Only now does it occur to me that the Princess Royal was the first member of the Royal Family I ever saw close to, as opposed to taking part in a distant ceremony. I was 8 years old and walking along Brompton Road with my mother. We saw a small crowd gathered outside Lord Roberts’s Workshops, more or less opposite Harrods. It seems that the Princess paid them an annual visit each November and this I worked out was on 6 November 1959. Presently she came out and walked to her car. We got such a good view of her. I remember being sad when she died, relatively young, in 1965.

Now, at last, I have been able to read her whole story.

Hugo Vickers

October 2020

Preface

On a magnificent spring morning in April 2011 Catherine Middleton, a commoner, processed down the aisle of Westminster Abbey in an Alexander McQueen dress of ivory satin and gazar silk, while the uplifting sound of Sir Hubert Parry’s choral anthem ‘I was glad’ filled the nave. After the ceremony, and accompanied by a full peal of bells, she emerged radiantly from the abbey; a royal princess and a possible future queen. There was much joyous celebration, with over a million people lining the route from the abbey. As the new bride made her way on to the Buckingham Palace balcony she was seen to exclaim, ‘Wow!’ at her first glimpse of the crowds who had surged past the Queen Victoria Memorial in order to demonstrate their approval. The sun shone even brighter that day on the new golden couple, whom everyone believed would bring some much-needed fresh blood and humanity to the royal family. Hailed as the ‘wedding of the century’, here was the living embodiment of a fairy tale; a prince and future king had married a beautiful young woman for love, rather than any political or dynastic alliance. Catherine was a new breed of princess, for a modern age of monarchy.

Within a few weeks, Catherine had already begun her philanthropic work championing the causes most significant to her, such as vulnerable women and children, the homeless, mental health and addiction. In lieu of receiving gifts for their wedding, Catherine and William established the Royal Wedding Charity Fund to support their charities. Catherine is considered to be a down-to-earth princess who is strongly aware of social issues and takes a hands-on role in all her charity work, such as designing a garden for children at Chelsea to inspire families to go outdoors into nature, donating her hair to cancer victims as part of the Little Princess Trust, working as a ‘secret’ midwife in order to raise awareness of their work, speaking on a podcast of her own difficulties when first becoming a mother.

Some might believe that her behaviour as a princess is modelled greatly on her late mother-in-law, Diana, Princess of Wales. Certainly, Diana was not afraid to take on causes that were unpopular at the time, such as leprosy and HIV. Diana was far more tactile and involved in her royal duties and she was the first member of the royal family to shake hands with a sufferer of AIDS. We tend to believe that it was Diana who first ripped up the royal rule book that determined how a princess should behave in modern times. We could not be further from the truth.

When they married, both Diana and Catherine continued a royal bridal tradition of honouring the war dead by placing their bridal bouquets on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Westminster Abbey. In doing so, they were continuing a tradition started in 1922 by a royal bride who stopped during the ride back to her wedding breakfast at Buckingham Palace and laid a bouquet on the Cenotaph to honour the dead from the First World War. Her name was Princess Mary, and she was the only daughter of the present queen’s grandfather, King George V, and his wife, Queen Mary.

Today Princess Mary remains relatively unknown. Few people know who she was or what she looked like and yet so many modern princesses owe her a debt of gratitude for the way she paved for them in ensuring that a princess’s life was not just about standing around looking pretty and organising social gatherings. Mary wanted to make a difference in her work and, more than anything, she wished to use her elevated position to help those who were less fortunate than herself. What makes this even more remarkable is that she was born during Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, a time of deference to the crown and solemnity.

Princess Mary was Britain’s first modern princess. This is evident from a glance at some of her most significant charitable achievements. During the First World War she visited hospitals and welfare organisations with her mother, Queen Mary. In particular, she was involved with charities supporting the wives and children of soldiers serving in France. She organised the Princess Mary Gift Fund during the First World War as a way of ensuring British troops and sailors received a Christmas gift. She worked in a canteen in a munitions factory in Hayes. But her main interest lay in nursing, especially the work of the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD). Mary trained to be a nurse and worked on a ward at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Princess Mary was one of the hardest working members of the royal family. She was known as the ‘Queen of the North’, a title given because she lived at Harewood in Yorkshire and because the number of royal engagements that she undertook, mainly in the north of England, was monumental. In 1922 Mary married the much older heir to the Earldom of Harewood, Henry Lascelles. Mary spent over thirty years living at Harewood House in Yorkshire from 1930. Harewood is a magnificent stately home that houses many treasures including art from the Renaissance and Chippendale furniture, as well as landscapes designed by Capability Brown. Mary took a keen interest in the interior decoration and renovation of Harewood.

Yet Mary was the daughter of a king and the sister of two others, as well as being the aunt of the current queen, Elizabeth II. Mary held a unique position in many key events and meetings in twentieth-century royal history. She witnessed how George V had to adapt the monarchy to ensure its survival at a particularly turbulent time following the fall of the empires of his first cousins Nicholas II of Russia and Wilhelm II of Germany. Similarly, after the First World War, the monarchies of Austria, Greece and Spain fell to revolution and war. George V changed the name of the royal family to Windsor in 1917 as a result of anti-German public sentiment. He was the first monarch to give a Christmas speech in 1932. He understood the importance of being visible to his subjects and he established a standard of conduct for British royalty that reflected the upper middle class rather than the upper class.

Mary was the sister of Edward, Prince of Wales, later Edward VIII and ultimately the Duke of Windsor. As siblings they were very close. Mary saw at first hand the full implications and issues surrounding the abdication crisis of 1936. Mary was the first royal to visit Edward VIII in exile and would always spend time with him when he returned for brief periods to England. She was one of the first members of the royal family to meet the Duchess of Windsor, albeit not until 1953.

In history books and in most royal biographies, Mary appears only briefly. She usually merits little more than the odd page or footnote. In many cases this lack of coverage has led to many misconceptions. Only recently the film Downton Abbey portrayed Mary as something of a forlorn and insipid woman, struggling within an unhappy arranged marriage. Other rumours abound: her childhood was unhappy and she refused to attend Princess Elizabeth’s wedding because the Duke of Windsor was not invited. I find it unbelievable that someone who has contributed so much to the nation by her devotion to duty can be so easily overlooked and so misunderstood. My aim in writing this book is to redress this balance and to ensure we never forget the debt of gratitude that we owe to Princess Mary for redefining the role of a princess in the modern age.

1

The Birth of a Princess

Heard from Georgie that May had given birth to a little girl, both doing well. It is strange that this child should be born on dear Alice’s birthday, … the last was on the anniversary of her death.1

Queen Victoria’s diary, 25 April 1897

Princess Victoria Alexandra Alice Mary, known as Princess Mary, was born on 25 April 1897 at York Cottage on the Sandringham estate. She was the third child and only daughter of the then Duke and Duchess of York, who would later become George V and Queen Mary. Mary’s father, Prince George, Duke of York, was the only surviving son of the direct heir to the throne, Edward, the Prince of Wales, and his wife Alexandra, the Princess of Wales, who would in 1901 become King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. The year of Mary’s birth was known more for the Jubilee celebrations of her great-grandmother, Queen Victoria, who by this time had been on the throne for a monumental sixty years. In 1897, the average life expectancy was a mere forty to forty-five years; thus Victoria had been monarch throughout most people’s lives. Princess Mary would witness no fewer than six monarchs in her lifetime.

The United Kingdom of 1897 was a far cry from the realm Victoria had inherited in 1837. In the same way that our modern Elizabethan age has witnessed vast sociological, cultural, scientific, technological and political changes, Victoria’s era was a time of radical advancements. The British Empire grew significantly during her reign and at its peak made up a quarter of the world’s population. The Diamond Jubilee public holiday of 22 June brought hundreds of thousands of people to witness the royal parade and service of thanksgiving. ‘The crowds were quite indescribable & their enthusiasm truly marvellous & deeply touching,’ Victoria recorded in her diary.2

When she acceded to the throne Victoria’s position was precarious, with only a handful of royal family members in the line of succession. However, by the end of her reign, Victoria was known as the ‘Grandmother of Europe’ having over thirty living adult grandchildren. She ensured not just the survival of her direct line but that of many European monarchies, including Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Spain. Even within her own family, Victoria was regarded ‘as a divinity of whom even her own family stood in awe’.3

Princess Mary’s mother was Princess Victoria Mary of Teck, known in the family as May. Princess May was the eldest child and only daughter of Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge and Francis, Duke of Teck. Francis was the child of a morganatic marriage (a marriage between two people of unequal social rank), meaning that he had no rights of succession to the Kingdom of Württemberg and was therefore a mere serene highness – though later HH The Duke of Teck. Finding a marriage partner for him had been difficult. Mary Adelaide of Cambridge was a granddaughter of George III, and for some time was in the direct line of succession. However, she also experienced similar difficulties in finding a marriage partner because of her colossal physical size. English historian and writer Janet Ross, who knew Mary Adelaide from their adolescence, recounted in her memoirs an occasion at a ball at Orleans House in Twickenham when the princess was dancing with the Comte de Paris: she ‘collided with me in the lancers and knocked me flat down on my back’.4 The American ambassador in London, Benjamin Moran, described her in 1857 (when she was 24) as being ‘very thick-set’, declaring her to weigh at least 250lb.5 Regardless of this, Mary Adelaide was known for her genial and ebullient nature. In 1883, Janet Ross and Mary Adelaide were reacquainted in Florence when both were living there to ease their financial difficulties. Janet remarked that ‘few women possess the charm of the Duchess of Teck; she took interest in everybody and her ringing laugh … would have made even a misanthrope smile’.6

Despite their arranged marriage, Mary Adelaide and Francis seemed to enjoy their life together, socialising and assisting in court events. The birth of their first child and only daughter, May, at Kensington Palace in 1867 appeared to complete their happiness. In journalist Clement Kinloch-Cooke’s authorised memoir of Mary Adelaide, we see an ideal picture of domesticity, with May’s father, Francis, unusually for a man in his position at this time, relishing the chance to enter the nursery in order to bathe his baby. In a letter to her close friend and royal courtier Lady Elizabeth Adeane (later Biddulph) on 6 March 1868, Mary Adelaide talks at length about her love for her baby: ‘She really is as sweet and engaging a child as you can wish to see … In a word, a model of a baby … “May” wins all hearts with her bright face and smile and pretty endearing ways.’7 Mary Adelaide and Francis went on to have three sons: Adolphus (1868), Francis (1870) and Alexander (1874).

Despite their seemingly perfect view of domestic bliss, Mary Adelaide’s propensity for partying and her generous charitable benevolence (she gave away a fifth of her income) meant that the £5,000 annual allowance from Queen Victoria was simply not enough for her to maintain her lifestyle. In 1883, the family had to move overseas for two years to escape their creditors. They hoped that by living off the benevolence of relatives they could in some way reduce their debts. They travelled to Italy, Germany and Austria, settling mainly in Florence. At first they went to the private Hotel Paoli on the Lungarno, frequently patronised by the English, and then to the Villa I Cedri at Bagno a Ripoli for the spring, a few miles outside Porta San Nicolo, to the south east of Florence. As one contemporary wrote:

The various circles of Florentine society vied with each other in their desire to make the Duchess of Teck’s stay pleasant and agreeable. It was of course, a great pleasure to the English residents to have Princess Mary (Adelaide) amongst them and her kindness of heart and personal charm endeared her to all who had the privilege of being presented to her.8

It was here that Mary Adelaide’s daughter, Princess May, developed an interest in Italian culture, spending much time visiting theatres, galleries, museums and churches. This would later inspire her appreciation of art and collecting, something May passed on to her daughter. There were daily visits to view the Old Masters in Florence such as Raphael, Van Dyck and Titian, along with lessons in singing, Italian and art.

The family returned to England in 1885 and made their home at White Lodge in Richmond. Princess Mary Adelaide was well known for her kindness towards her neighbours and the poor and was eager that her children should learn an empathy with those less fortunate. Kinloch-Cooke recalls in his biography of Mary Adelaide:

On one occasion, her Royal Highness was taking a stroll … and came across an old woman picking up sticks; the woman seemed tired and the day was cold. Very soon the Duchess was hard at work, pulling down the dead wood from the lower branches of the tree with her umbrella.9

This incident was far from unique for Mary Adelaide, who was the first royal to earn the nickname of ‘People’s Princess’ and took pride in assisting the poor. There are accounts of Mary Adelaide supporting neighbouring village fetes and bazaars, helping on stalls to boost sales. This was a trait that she was eager to pass on to her children, who learned the struggles of the lower classes by being taken to visit tenements and hovels. In addition, Mary Adelaide involved Princess May in the work of the Surrey Needlework Guild and the Royal Cambridge Asylum, as well as the Victoria Home for Invalid Children in Margate. Mary Adelaide was an early patron of such charities as Dr Barnardo’s, the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children and the St John Ambulance Association. A publication produced in 1893, The Gentlewoman’s Royal Record of the Wedding of Princess May and The Duke of York, describes Princess Mary Adelaide as ‘one of the most respected and beloved members of our Royal house, whose energy in charitable and philanthropic work deserves the nation’s gratitude’.10

In 1886, the young Princess May, who was described as ‘a remarkably attractive girl, rather silent, but with a look of quiet determination mixed with kindliness’,11 made her debut at court. It was no wonder that she was shy, with such an outspoken and gregarious mother. Yet this slightly aloof and dignified manner soon made her a firm favourite of Queen Victoria and she was singled out as a potential bride for Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, known as Eddy, who was the eldest child and heir of Victoria’s heir, Edward, the Prince of Wales. In December 1891 their engagement was announced and as Mary Adelaide remarked in a letter to Lady Salisbury, ‘Eddy is radiant and looks it and our darling May is very happy, though at times her heart misgives her lest she may not be able fully to realise all the expectations centred in her.’12 Queen Victoria herself was pleased with the match and in her diary noted that ‘I was quite delighted. God bless them both. He seemed very pleased & satisfied, I am so thankful, as I had much wished for this marriage, thinking her so suitable.’13

If May had misgivings about the match, these were well founded. Prince Eddy had, in his grandmother’s words, lived something of a ‘dissipated life’.14 The match between his parents Bertie (Prince Edward) and Alix (Princess Alexandra) had come as something of a relief to Queen Victoria. Unlike his father, the saintly, moralistic, Prince Albert, Bertie enjoyed the company of women and living life’s pleasures to excess. Alix was a Danish princess and had been chosen as Bertie’s wife for her beauty and discretion. The marriage was relatively content, although Bertie continued to have affairs with many society beauties and actresses. In response, Alix gave all of her – at times, suffocating and possessive – love to her five children: two boys, Eddy and George, and three girls, Louise, Victoria and Maud.

Eddy inherited his mother’s tall, sinewy frame, yet Queen Victoria viewed Bertie and Alix’s children as fairy-like and puny, and this may be why so many later historians took to depicting Eddy as sickly and weak. A contemporary source states that ‘the child was not … either weakly or delicate … his general health, indeed, gave no cause for anxiety’.15

The life of Bertie and Alix and their Marlborough House set was filled with hunting and shooting parties, balls, race meetings and family gatherings and travel. Wanting to install some discipline into the young princes, in 1871 Queen Victoria appointed Canon John Neale-Dalton to tutor Eddy and George. At times, Dalton despaired at the lack of routine and stability that clearly prevented him from making progress with his charges. Dalton was ahead of his time in some ways, preferring to focus on how to learn rather than what to learn; by teaching his pupils life skills rather than cramming them with facts.16 By all accounts Dalton established an exacting curriculum for the two boys in his care, believing that they should receive a thorough grounding not just in academia, but also in physical pursuits, as well as the pastimes of country gentlemen such as hunting and shooting. Prince George was considered a good influence on his brother academically and so the princes remained together. Bertie was eager for his sons to escape the harsh regime of the schoolroom that he had been forced to endure under Prince Albert, and he wanted them to see for themselves the constantly expanding British Empire. With Dalton’s support, he managed to persuade his mother that the boys would benefit from a cadetship aboard HMS Britannia in Dartmouth. This was followed by three years aboard the Bacchante and, for Eddy, Trinity College Cambridge and later a stint with the Tenth Royal Hussars, the Prince of Wales’s regiment.

Although he was said to possess a benevolent nature, Eddy had scant regard for intellectualism or diligence. Rumours abounded of his predilection for chorus girls and partying. Queen Victoria thought marriage would be the only solution to curb the unstable and immoral prince. She invited Princess May and her brother Adolphus to Balmoral in November 1891, where she could see for herself if May would be a suitable wife for Eddy and found her ‘a dear charming girl and so sensible and unfrivolous’.17

Thus, on 3 December 1891, at Luton Hoo in Bedfordshire, Eddy proposed to May. ‘To my great surprise, Eddy proposed to me during the evening … Of course I said yes. We are both very happy.’18 The engagement was announced with preparations in place for a wedding the following February. Queen Victoria was so pleased with the engagement that on 12 December she took the happy couple to Prince Albert’s mausoleum for his ‘blessing’. For May, brought up to feel that she was somehow less than royal, with her father’s morganatic background and her family’s recurrent insolvency, this must have seemed tantamount to securing the greatest royal marital prize. She could look forward to becoming the Duchess of Clarence, the future Princess of Wales and ultimately Queen of England.

Sadly, that winter saw a tragic reversal in Princess May’s circumstances, caused by a national pandemic of influenza. In early January, Eddy came down with the illness while out shooting at Sandringham and within a few days he had developed pneumonia. He died on 14 January 1892. As Queen Victoria wrote in her diary: ‘Poor May, to have her whole bright future to be merely a dream. …This is an awful blow to the Country too! We are all greatly upset. — The feeling of grief immense.’19 Eddy’s younger brother, George, was second in line to the throne. The family were all deeply affected by such a sudden passing. In a letter to his mother, which she recorded in her diaries, Bertie related that:

Poor Boy, he battled so strongly against death ... The poison of that horrid influenza had got into the dear boy’s brain and lungs, and baffled all science ... to rob us of our eldest son, on the eve of his marriage. Gladly would I have given my life for his, as I put no value on mine.20

The feeling among the people was of shock and upset at such a premature ending to a life. There was a huge outpouring of grief and immense sympathy for the royal family, not unlike the public demonstrations following the tragic death of Diana, Princess of Wales in 1997. The following day, the Western Gazette reported:

The death of the Duke of Clarence plunges millions of all ages, classes, and races in this kingdom into a sorrow of profound acuteness, and into the keenest sympathy with the Prince and Princess of Wales, the Princess May, and every member of the Royal House, who at this hour are so sorely stricken.21

Prince George had suffered from typhoid fever just before his brother’s untimely death and there were concerns over the succession. The next in line after George was his timid sister, Princess Louise, who had married a mere earl (later Duke and Duchess of Fife) and had thus far only produced a living daughter. In addition, there was a shortage of suitable foreign princesses available to marry the heir to the British throne. George had shown an attraction for his cousin, Princess Marie of Edinburgh, ‘Missy’, but George’s mother, Alix, and Missy’s mother, the Duchess of Edinburgh, were both opposed to the match. While serving in the navy, he developed a fondness for a commoner, Julie Stonor, who as a Roman Catholic was equally unsuitable. Princess May’s parents were determined that their daughter should not lose out on marriage to the heir and so they deliberately took May to Cannes to recover from her sorrow, where Bertie and his family were staying on his yacht, Nerine.

It was natural that May would develop a closeness with Eddy’s surviving brother, Prince George, as they were both struggling with grief. Wherever she went in Cannes, Princess May was greeted with compassion for her loss from the locals. Once on a walk to the flower market, when accompanied by Bertie and Prince George, she was overwhelmed by the many bouquets given to her by the people. ‘The Prince and George … were completely enchanted by this show of well-bred sentiment towards May on the part of perfect strangers.’22 As early as 6 September 1892, the Dundee Courier reported that ‘the rumour is being revived that Prince George and Princess May of Teck will be married, probably in January next’.23 By February 1893 there was still much speculation that an announcement would be imminent. Lloyds Weekly Newspaper reported on Sunday 12 February that ‘she has felt greatly pained at the frequent speculations as to her future which have appeared during the past twelve months of her sadness’. 24

On 3 May 1893 at Sheen Lodge, the home of his sister, Princess Louise, Duchess of Fife, Prince George finally plucked up the courage to ask Princess May to marry him. Both George and May were incredibly reserved and all the gossip and speculation surrounding their possible betrothal must have made the situation awkward for both. As Princess Arthur of Connaught later related:

I don’t know whether he was … shy of her … but … he was just about to leave the house without having proposed so [Princess Louise] said to him ‘Georgie, don’t you think you ought to take May out into the garden and show her the frogs in the pond?’ and when they came back, he told them he was engaged.25

The marriage ceremony was arranged to be held in the Chapel Royal on 6 July during an ‘overpoweringly hot’26 heatwave. Queen Victoria remarked that ‘it was really (on a smaller scale) like the Jubilee, & the crowds, the loyalty & enthusiasm were immense. — Telegrams began pouring in from an early hour … whilst I was still in bed, I heard this distant hum of the people’.27

The newly married and named Duke and Duchess of York were given a suite of apartments at St James’s Palace, to be known as York House, for their London base, and a small house on the Sandringham estate known as York Cottage, where they honeymooned. York Cottage had once been known as the Bachelors’ Cottage and was designed to accommodate any overspill of guests from the main Sandringham house. Designed in an eclectic mix of jarring architectural styles, it was relatively small, especially for a growing family, more akin to a suburban house and yet it would become the favoured home of the couple for the following thirty-three years. Writing to her eldest daughter Vicky, Queen Victoria described it as it ‘rather unlucky and sad’.28

Yet George disliked entertaining and such a small home ensured that visitors would be few. Furthermore, with his naval background he felt more at home in small, cluttered rooms that reminded him of life on board a ship. His eldest son, Edward, Duke of Windsor, known in the family as David, later said to George’s official biographer, Harold Nicolson, ‘Until you have seen York Cottage you will never understand my father. It was and remains a glum little villa. It is almost incredible that the heir to so vast a heritage lived in this horrible little house.’29

In a misguided gesture of kindness, to save his bride the task of furnishing their marital home, Prince George had already decorated the house with modern reproduction furniture from the popular London retailer and cabinet maker Maple and Co. May, with her love of interior design and art, found this infuriating.30 In addition, their early marital days at York Cottage were frequently disrupted by the constant and boisterous visits of George’s mother, Alexandra, and his sisters, Maud and Victoria, who lived in the neighbouring main house. Alexandra would on occasion rearrange furniture in York Cottage to suit her own tastes rather than respecting May’s position as lady of the house.

Despite this challenging start, and with both struggling with their timidity to express themselves to each other, within a few months a gentle fondness had matured into something far deeper, shown in a letter George wrote to May:

I know I am, at least I am vain enough to think that I am capable of loving anybody (who returns my love) with all my heart and soul, and I am sure I have found that person in my sweet little May … When I asked you to marry me, I was very fond of you, but not very much in love with you, but I saw in you the person I was capable of loving most deeply … I have tried to understand you and to know you and with the happy result that I know now that … I adore you sweet May, I can’t say more than that.31

Their first child, Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, known in the family as David, was born almost a year after the wedding on 23 June 1894 at White Lodge in Richmond Park. They would go on to have five more children, who were all born at York Cottage on the Sandringham estate: Albert (known in the family as Bertie), Mary, Henry, George and John.

2

Childhood and Education

Spirit of well-shot woodcock, partridge, snipe

Flutter and bear him up the Norfolk sky:

In that red house in a red mahogany bookcase

The stamp collection waits with mounts long dry.

‘Death of King George V’

John Betjeman

York Cottage was already proving to be far too small for the growing family of the Duke and Duchess of York, even with the addition of a three-storey wing. Two rooms on the first floor were set aside as a nursery. ‘I shall soon have a regiment, not a family,’1 George remarked at the rapid arrival of six children. On 7 June 1897 George and May’s only daughter, known as Princess Mary, was baptised by the Archbishop of York, Dr William Maclagan, at St Mary Magdalen’s Church near Sandringham. Her godparents were Queen Victoria, Princess Mary Adelaide, Empress Marie of Russia, Princess Victoria, King George of the Hellenes and the Earl of Athlone (then Prince Alexander of Teck).

In marked contrast to his own upbringing, George preferred to raise his children with a simpler and quieter life at York Cottage. As his diaries later revealed, George was a stickler for punctuality with an obsession over the weather and uniforms. Never one to be considered in any way intellectual, George was at his happiest when involved in his two hobbies of stamp collecting, to which ‘delicious hours have been devoted’2 and shooting game: he ‘had thirty thousand acres over which to pursue pheasants and partridges, woodcock and duck’.3 George passed on this fixation and pride in wearing the correct uniform to his daughter, who wore the uniform of the VAD while training to be a nurse. During the Second World War she was rarely seen out of her ATS attire.