Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

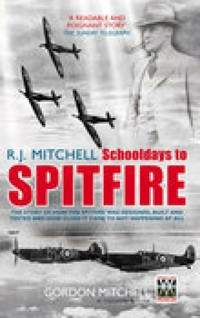

The Spitfire began as a near disaster. The developments of this famous aircraft took it from uncompromising beginnings to become the legendary last memorial to a great man - an elegant and, with its pilots, a highly effective, weapon of war. The Spitfire would not have happened at all, however, without Mitchell's indomitable courage and determination in the face of severe physical and psychological adversity resulting from cancer. His contribution to the Battle of Britain, and thereafter to the achievement of final victory in 1945, was so great that our debt to him can never be repaid. This poignant story is written from a uniquely personal viewpoint by his son, Gordon Mitchell.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 718

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This edition first published 2006

Tempus Publishing Limited

The Mill, Brimscombe Port,

Stroud, Gloucestershire, gl5 2qg

www.tempus-publishing.com

© Gordon Mitchell, 1986, 1997, 2002, 2006

The right of Gordon Mitchell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9780 7524 7448 9

Typesetting and origination by Tempus Publishing Limited

Printed and bound in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

About the Author

List of Appendices

Abbreviations

Foreword

Introduction

Acknowledgements

Reference Sources

Appreciation

The Author

1 R.J. Mitchell

2 Supermarine

3 The Schneider Trophy

4 The Americans at Cowes

5 A Royal Visit to Supermarine

6 The S.4

7 The Southampton Flying Boat

8 The S.5: A Triumph for Mitchell

9 Welcome Home

10 The S.6: Victory at Cowes

11 1931: Britain Wins the Schneider Trophy Outright

12 The Last of Mitchell’s Flying Boats and Amphibians

13 The Spitfire

14 Mitchell’s Death

15 The Spitfire Goes to War

16 Development of the Spitfire

17 Production of the Spitfire 1940–45

18 My Father as I Remember Him

19 Memorials, Tributes and Events Associated with R.J. Mitchell

20 The Role of the Spitfire in the Battle of Britain

Appendices

Notes

Illustrations

About the Author

Dr Gordon Mitchell PhD CBiol FIBiol is the son of R.J. Mitchell, and was until his retirement a biologist at the University of Reading. He is still, aged 85, an active member of the Spitfire Society. He lives in Cheltenham.

Appendices

1 R.J. Mitchell – Aircraft Designer by Sir George Edwards, OM, CBE, FRS, FEng

2 The Spitfire from Prototype to Mk 24 by Air Marshal Sir Humphrey Edwardes Jones, KCB, CBE, DFC, AFC

3 Wonderful Years by Alan Clifton, MBE, BSc(Eng), CEng, FRAeS

4 R.J. Mitchell as seen through the eyes of an Apprentice by Jack Davis, CEng, MRAeS

5 The Man I worked with for Thirteen Years by Ernest Mansbridge, BSc(Eng), CEng, MRAeS

6 A Chief Test Pilot’s Appreciation of R.J. Mitchell by Jeffrey Quill, OBE, AFC, FRAeS

7 My Experiences with the Spitfire at Supermarine and at Castle Bromwich from 1939 to 1946 by Alex Henshaw, MBE

8 Memories of the 1931 Schneider Trophy Contest by Group Captain Leonard Snaith, CB, AFC

9 Tributes from a Few of the Many who flew the Spitfire into Battle by Air Commodore Alan Deere, DSO, OBE, DFC; Air Vice-Marshal ‘Johnnie’ Johnson, CB, CBE, DSO, DFC, DL; Wing Commander Bob Stanford-Tuck, DSO, DFC, RAF (Retired); Flight Lieutenant Denis Sweeting, DFC

10 A Spitfire Wing Leader looks back by Group Captain Duncan Smith, DSO, DFC, AE, RAF (Retired)

11 The Royal Navy called them Seafires by Captain George Baldwin, CBE, DSC, RN (Retired)

12 Senior Members of Mitchell’s Team at Supermarine in or around 1936

13 Family Tree of R.J. Mitchell

14 Number of Spitfires and Seafires existing as at January 2002

15 Test Flight Record No. N/300/1 of f.37/34 Fighter 4 K5054

Abbreviations Used

AC – Air Commodore

ACM – Air Chief Marshal

AM – Air Marshal

AVM – Air Vice-Marshal

CO – Commanding Officer

MRF – Marshal of the Royal Air Force

The book is an absolutely first-class effort, and I hope very much that it achieves the success it deserves.

Sir George Edwards, OM, CBE, FRS, FEng (April 1986)

Your book relates the sad and poignant story about the life of not only the most outstanding aircraft designer of my time but also of a man of incredible moral and physical courage. I think that it will be recognised as the classic narrative on the birth of the Spitfire and will put all other publications in the shade.

Alex Henshaw, MBE (April 1986)

You are to be much congratulated on your book about R.J. A very thorough job and I feel R.J. would have been pleased with it. It fills a much-needed gap in the literature of aviation.

The late Jeffrey Quill, OBE, AFC, FRAeS (March 1986)

The Spitfire fighter – the most renowned of all fighter aircraft in the war of 1939–45. Mitchell wedded good engineering to aerodynamic grace and made science his guide. The Spitfire exemplified Mitchell’s special quality of combining fine lines with great structural strength.

Colston Shepherd (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 1949 Edition. By permission of Oxford University Press)

Your dad was one of the greatest men of the twentieth century and provided the free world with a superb weapon.

Dr Derek Armstrong, Ontario, Canada (July 2000)

Dear Dr Mitchell, The Prime Minister fully understands your wish to see that your father’s services to aircraft design are recognised with a posthumous high honour.

Letter received from 10 Downing Street (December 1999)

I have no doubt that your father’s design will still be flying a hundred years after the aircraft’s first flight, and giving pilots and aviation lovers the same pleasure as it has for the past sixty-four years.

ACM Sir Peter Squire KCB, DFC, AFC, ADC, FRAeS, RAF (September 2000)

Unlike some men who achieve considerable success when young, it was quite obvious that R.J.’s success had not gone to his head and it never did. A man in a million.

From Never a Dull Moment by Denis Le P. Webb – at Supermarine for forty-four years from 1926 (May 2001)

For Gordon with best wishes and a salute for your father without whose genius we could not have won the Malta battle of 1942. Ask those who were there.

The late Wg Cdr P.B. ‘Laddie’ Lucas, CBE, DSO (and Bar) (c.1995)

Your book has been a useful source for this work (Swift Justice) and is essential reading for Supermarine watchers.

Grp Capt. Nigel Walpole, OBE, BA, RAF (Author of Swift Justice, May 2000)

Website (2006) www.rjmitchell-spitfire.co.uk

Foreword

by The Right Honourable The Lord Balfour of Inchrye, PC, MC,Under Secretary of State for Air, 1938–1944

I know I fell in love with her the moment I was introduced that summer day in 1938. I was captivated by her sheer beauty; she was slimly built with a beautifully proportioned body and graceful curves just where they should be. In every way to every young man – or, in my case, middle-aged man – she looked the dream of what one sought. Mind you, some of her admirers warned me that she was what mother called ‘a fast girl’, and advised that no liberties should be taken with her until you got better acquainted.

I was warned to approach her gently but once safely embraced in her arms I found myself reaching heights of delight I had never before experienced.

Thus was my introduction to that early Spitfire, the consummation of R.J. Mitchell’s design work of sixteen years, supported by a team of colleagues without whom, as he was always at pains to stress, he could never have achieved all that he did.

Success could only have been won by hard work, knowledge and intense determination during those pre-Spitfire years of development. Not everyone connects Mitchell’s ultimate success with the creations of his earlier work. Back in 1922, there was the Sea Lion II, winner of that year’s Schneider Trophy race; later came his work producing the Royal Air Force (RAF) twin-engined flying boats such as the Southampton, four of which carried out the famous 23,000-mile Far East Flight to India, Australia and Singapore in 1927–28; these were followed by further, ever-improving types such as the Stranraer flying boat, the ‘S’ series of racing seaplanes which won the Schneider Trophy outright for Britain, and last but not least the dear old Walrus amphibian of last war fame.

In truth, one can say that, in those pre-war years, the RAF was building up the nation’s debt to Mitchell, for, as is related within the pages of this book, he designed no less than twenty-four different types of aircraft during his life.

Then came the war, and the culmination of effort and achievement for R.J. Mitchell. The Spitfire came into its own. It would be presumptuous of me to dwell on how this short-range fighter of 1940 became the most versatile aircraft of the RAF. I cite some of the tasks it was used for, and always with great success: low and high offensive operation; ground force attack; high-altitude photo-reconnaissance; a range extended by the jettisonable slipper tank.

This book is a worthy tribute to R.J. Mitchell, to whom our country owes so much, for his work in a life sadly shortened while still full of promise. Within its pages I have read of the experiences of those men who ‘did the job’, and in admiration of their feats of bravery against the enemy. Sadly we remember those who paid the price with their lives.

I like to think that, somewhere, somehow, R.J. and they are once more in companionship.

Lord Balfour died on 21 September 1988.

Introduction

The leading role in this book is played by the man who has been rightly called one of the outstanding designers of all time, R.J. Mitchell (1895–1937).

The aircraft that he designed do, of course, figure in the narrative but they play a secondary role. Accordingly, this publication is different from all of the many others that have been written about one or other of these aircraft, in particular the Spitfire fighter, about which there appears to be a never-ending urge to write more and more. This book is not just about the Spitfire, laudable though it might be if it were, as within these pages the Spitfire takes its place alongside the twenty-three other aircraft that Mitchell designed in the sixteen years of his brief working life. In turn, these aircraft all take their rightful place a respectful distance behind their creator. Until now, relatively little has been written about Mitchell himself and certainly nothing in such detail as will be discovered within these pages. These are the true facts about the man who achieved so much in so short a time, the man who has been widely acclaimed to have been a genius and whose contribution to the survival of his country was of such magnitude that its debt to him can never be repaid. Mitchell’s story is part of the history of Britain and, within this book, it has at last been told in full.

What was my father really like; what training did he have that formed the foundation for such an outstandingly successful career; what did his colleagues who worked with him (probably the most exacting critics) and his test pilots really think of the man? How advanced were his creative ideas in aircraft design; did he have failures as well as successes; was Mitchell an artist in the true sense of the word as well as an engineering genius? Was he a born leader, actively directing and guiding his team of specialists, or was he perhaps really only a figurehead, doing very little and taking all the glory? How did the leaders of the aviation world assess him?

Answers to all these questions and many more personal observations will be found in these pages, including what my father was like to live with; whether he was a good and caring father; whether he was all work and no play, and what, if any, his interests were outside work; what his relationship was with my mother and myself and with his other relatives, and how his success in his career affected these relationships. Last, but by no means least, how did he face up to the severe physical and mental adversity that he had to suffer during the last four years of his life, which has never before been described in such detail?

Sufficient detail is given about all the important aircraft he designed to enable the non-specialist reader to assess his creative genius; also insights into how he learnt from the hard school of failure to turn failures into outstanding successes – how, for example, the first ‘Spitfire’ was a near disaster; and how he always proclaimed that he was ‘just one member of a team of experts’.

In addition to detailing the life story of R.J. Mitchell, this book contains many fine tributes from eminent people who either have a particular knowledge of Mitchell’s work, had a special association with his aircraft or who worked with him at Supermarine. I invited a number of people to contribute and all generously accepted; this is in itself a magnificent tribute to my father and my very grateful thanks are due to them all. I am also deeply conscious of the honour that the Rt Hon. The Lord Balfour of Inchrye accorded my father by readily agreeing to write the Foreword and I owe him my very sincere gratitude. As under secretary of state for air, Lord Balfour signed the first order for 310 Spitfires on 3 June 1936 and then later, in 1938, he himself flew half of the RAF’s complement, at that time, of two Spitfires!

I am greatly indebted to the late Marian Blackburn, who had the original idea for producing a book about my father, albeit aimed at schoolchildren. She had carried out much research for her proposed booklet, which proved to be of great value to me in the production of this book. I indeed owe Marian Blackburn a great debt of gratitude for sowing the seed which eventually germinated into the present volume.

One further person I wish to mention here is Jeffrey Quill, who gave valued help and advice with the book and, most importantly, rewrote large sections of Chapters 15, 16 and 17, since he felt that the first drafts did not do full justice to the subjects covered. There is no one better qualified to have done this, since Jeffrey’s long and distinguished association with the Spitfire is unique, and I am most grateful to him for so willingly undertaking this task.

I carried out as little editing as possible of the invited contributions; likewise no attempt was made to achieve a common style of writing, or to delete similar material being considered in different chapters, provided it was done from differing viewpoints.

Few books published are completely free of mistakes and doubtless this one will be no exception despite the attempt to make it so. Consolation may be obtained from the words of Winston Churchill, who suggested that the presence of mistakes, deliberate or otherwise, in published work could serve a useful purpose by leaving room for criticism, as a result of which the author and the work become better known! Nevertheless, any mistakes found herein are unintentional. In the event, relatively few mistakes were found and have been corrected in this revised Fourth Edition of the book.

My objectives in producing this book have been to achieve a publication that would be seen as the definitive life of R.J. Mitchell, that it would be interesting, informative, readable and authentic, and would be accepted as a worthy tribute to him. I became involved in the project because I was the son of that man, and was, as a result, in a unique position to help the achievement of these objectives. What I have done has been entirely on behalf of my father, for whom no son could have greater affection and pride, and I seek no recognition for myself. If my father had been alive today and his verdict after reading this book had been favourable, then I would have been well satisfied and would have wished for nothing more.

Gordon Mitchell

December 2005

Acknowledgements

It is impossible to produce a book such as this without being able to enlist the help of many people and I am very conscious of how much I owe to so many who so willingly gave this assistance.

Many of these have received mention in the Introduction; equally I am very indebted to Eric Mitchell, R.J.’s brother, and his wife, Ada, for providing material relating to R.J.’s early family life; to the following ex-colleagues of R.J. who talked about the years they had worked with him – Eric Lovell-Cooper, Jack Rasmussen, Arthur Shirvall and Harold Smith; to Mrs Vera Cherry who, as Miss Cross, was R.J.’s secretary for many years and spoke about her memories of those happy times; to Gladys Pickering, wife of the great test pilot George, both of whom knew R.J. and my mother for many years; to Bishop Reeve who recalled the visits he made to R.J. during the last months of his life; and to Mrs Eva Pitman who lived with the Mitchell family in their home in Southampton for a large number of years. Two others who likewise spoke to me about R.J. were Sir Stanley Hooker of Rolls-Royce and AVM ‘Webby’ Webster, winner of the 1927 Schneider Trophy.

Two people who must receive special mention are Alan Clifton, ex-colleague of R.J.’s, and Hugh Scrope, previously company secretary of Vickers plc. Alan is one of the contributors to the book but, in addition, he helped in several other ways over matters in which he was in a unique position to do so. Hugh seemed to thrive on answering questions, giving permission to use various material and providing invaluable information. I am most grateful to them both for their patience and guidance.

In addition, there is a very large number of people who gave help in a variety of ways, such as providing information, supplying photographs or other material, or giving valuable introductions to other people. Their names are given below in alphabetical order and I am very conscious of the debt of gratitude I owe to them all. Some have received acknowledgement in the text of the book but for completeness are included again here.

Michael Baylis (photographs), Wg Cdr David Bennett (information on memorials), Pat Bennett (son of Alec), Mrs M. Cecil (1927 letter of R.J.’s), Peter Cooke (Spitfire model photograph), Christopher Cornwell (bishop’s chaplain, Lichfield), A.E. Crew (Stoke-on-Trent Association of Engineers), H.J. Deakin (Reginald Mitchell CP School), Professor Robin East (University of Southampton), Christopher Elliott (RAF Museum – photographs of many of R.J.’s personal items held by the museum), Richard Falconer (R.J.’s old wrist-watch), Keith Fordyce (curator, Torbay Aircraft Museum), Campbell Gunston (Battle of Britain Memorial Flight), Ronald Howard (son of Leslie), Sqn Ldr Alan Jones (Southampton Hall of Aviation), Howard Jones (director of the British Colostomy Association), Professor Geoffrey Lilley (University of Southampton), the Hon. Patrick Lindsay (Christie’s Ltd), Peter March (Air Extra), David Mondey (author), S.S. Miles (sculptor), Eric Morgan (British Aerospace plc), Rosemary Mourant (Mitchell Junior School), A.W.L. Nayler (Royal Aeronautical Society), David Plastow (managing director and chief executive, Vickers plc), David Preston (public relations manager, Rolls-Royce Motors Ltd), RAF Museum, R.A. Randall (editor, Evening Sentinel), Richard Riding (editor, Aeroplane Monthly), Michael Ridley (curator of museums, Weymouth), David Roscoe (director, public relations, Vickers plc), Martin Snaith (son of Leonard), Southampton Reference Library staff, Cdr Dennis White (director, Fleet Air Arm Museum), Wg Cdr Bill Wood (RAF Museum).

Finally, I wish to record my sincere thanks to my wife, Alison, for her support and patience and for her invaluable assistance, prior to her death in April 2005, in the production of the book.

Gordon Mitchell

Reference Sources

Many references in various publications were consulted in the preparation of this book, but the following should be mentioned as being of particular value and importance:

J. Smith, JRAeS (1954) The First Mitchell Memorial Lecture, 58, 311–328.

David Mondey (1975) The Schneider Trophy.

C.F. Andrews & E.B. Morgan (1981) Supermarine Aircraft since 1914.

J.D. Scott (1962) Vickers: A History.

Appreciation

The Late R.J. Mitchell

This appreciation by Sir Robert McLean, chairman of Vickers Aviation Ltd, and of The Supermarine Aviation Works (Vickers) Ltd, was published in Vickers News in July 1937. It is reproduced in full by kind permission of Vickers plc.

By the death of Mr R.J. Mitchell at Southampton on 11 June, the world of aviation has lost one who has long been one of its outstanding figures.

After serving an apprenticeship with Messrs Kerr, Stuart & Co. Ltd, of Stoke-on-Trent, he joined the Supermarine company at the age of twenty-two in 1917, was appointed chief engineer and chief designer by 1920, and became a director of the company in 1928.

In 1927 he was awarded the silver medal of the Royal Aeronautical Society in recognition of his share in the British Schneider Cup victory at Venice, and in 1932 the CBE was conferred upon him in recognition of his services to aviation.

In the public mind his name will always be associated with the history of the Schneider Trophy, which, by virtue of the backing given to competing teams by their respective governments, became a grim technical competition with national prestige deeply involved.

In 1922, the Supermarine company had its first victory in the Schneider Trophy at Venice with a flying boat designed by Mitchell; and again in 1927, 1929 and 1931, the series of machines, which finally brought the trophy to Britain for all time, were products of his mind. All these contests and the demand for ever-increasing speed set the designer on each occasion a set of new and difficult problems, the wrong answers to which might end in disaster and loss of life. Those connected with Mitchell during these contests and their attendant anxieties will always remember how he seemed to have anticipated, and to be ready for, any doubts or difficulties which might arise in the execution of the task. It is significant that while other nations applied their best design brains to the production of seaplanes to compete in the Schneider Trophy, it was only Mitchell who, on each occasion, was ready with his machines in time to come over the starting line on the appointed day.

Not the least of his services to the country was the stimulus that these victories gave to British aeronautical technique and the realisation by the public that, in this new adventure of flying, British technique was supreme.

How well he succeeded in combining superb aeronautical design with an adventurous, but always sound, structural technique, is witnessed by the firm’s record of service types. There have been the early ‘Seagull’, an amphibian of which many went into service in Spain and Australia; the ‘Southampton’, long the standard twin-engined flying boat in the RAF; followed quickly by the ‘Scapa’ and the ‘Stranraer’; all bearing upon them the ‘Mitchell’ mark of originality, coupled with thoroughly sound execution. With the revival of the amphibian idea in the ‘Seagull V’, there became available for the Naval Air Service, under the naval name of ‘Walrus’, a new amphibian for use with the Fleet Air Arm. Of the machines most recently completed by Mitchell, the ‘Spitfire’, a single-seater fighter, reflects more closely the immense knowledge gained in high-speed work in his Schneider Trophy days. When the achievements of this aircraft come to be made public, it will be recognised that once again he stood head and shoulders above competitors in his solution of a difficult problem.

The impression left on the mind of one who had been in the closest contact with Mitchell for many years in his plans for the future, and in his views on these new problems that arise from day to day in the evolution of flying, was that of a critical mind, not prepared to jump to conclusions or take decisions except on grounds of whose soundness he had satisfied himself. At the same time, no idea was too daring or adventurous to be considered, never from the academic point of view, but always from that of practical application.

Mitchell leaves a record of almost continuous achievement which has not been equalled by any other individual designer in the short history of aviation, and his death at the early age of forty-two is indeed a tragedy. His colleagues and friends can but express to his widow and son their deep sympathy in the sorrow which has overtaken them.

Sir Robert McLean

The Author

Dr Gordon Mitchell, PhD, CBiol, FIBiol

Gordon Mitchell was born on 6 November 1920, the only offspring of the family. After leaving school, he worked on a farm in Dorset as a pupil for one year and then entered the University of Reading in September 1940 as an undergraduate. After two years, he voluntarily gave up his university studies to join the RAFVR in which he served for five years. First he served on Air-Sea Rescue High Speed Launches, and then in September 1944 he was commissioned in the Meteorological Branch. On demobilisation in February 1947, Gordon returned to Reading University to complete his degree course, and obtained his degree in 1948. Shortly afterwards, he secured a post at the University of Reading’s National Institute for Research in Dairying, where he remained until he retired in March 1985. He conducted research studies on the nutrition of farm animals, specialising in the pig, which has a close similarity to man in many nutritional and physiological features. He was the author or co-author of many papers published in scientific journals.

He became a member of the academic staff of the University of Reading in 1952 and the following year obtained his PhD degree. He served for three years on the senate of the university from 1969, and as technical secretary on a number of committees and working parties concerned with animal nutrition and allied subjects. He was a member of the executive committee of the Institute of Biology, Agricultural Sciences Division, for a number of years, and later became chairman of this committee. Likewise, he served for several years on the council of the British Society of Animal Production; he was also an elected member of the John Hammond Pig Group and served for a year as chairman of this influential group of advisory, genetic, producer, research, university and veterinary specialists.

Gordon was elected a fellow of the Institute of Biology in October 1979 and for the final six years of his appointment at the NIRD he was head of his department. On retirement, the title of honorary fellow of the University of Reading was conferred upon him, which he was very proud to have been granted. He was also granted the status of honorary research associate of the university’s associated institution, the Animal and Grassland Research Institute.

Gordon Mitchell has been a vice-president of the James Butcher Housing Association Ltd in Reading since 1969; in November 1985 he and his wife opened a new specialised nursing unit, bearing the name Mitchell Lodge in recognition of their long connection with the association. He is an active member of the Spitfire Society and of the Bourton-on-the-Water Probus Club.

Following his retirement, he devoted much of his time to the production of this book, its Second Edition in 1997, its Third Edition in 2002, and now, in 2006, this current Fourth Edition, but does not, he says, have plans to write any more! In 1993, Gordon started a campaign to persuade the Royal Mail and the Royal Mint to honour his father, on the occasion of the centenary of his birth on 20 May 1995, in some appropriate way. The success of this long campaign is detailed in Chapter 19.

Since 1989, Gordon has been giving lectures about his father to raise funds for Cancer Research UK (R.J. Mitchell Fund). As at January 2006, he has given 136 lectures and raised a total of £28,232 for the fund. All the money he raises for this designated fund is used for research in colorectal cancer, the form of cancer from which his father died in 1937. His mother died from bladder cancer on 3 January 1946. Gordon is a life governor of Cancer Research UK.

He had been happily married to Alison, whom he describes as a super wife, for fifty-five years when sadly she died on 30 April 2005. He has a family of three, David, Adrian and Penny. In October 1985 he became a proud grandfather for the first time, and in October 1988 for the second time – Nicky and Emma.

Shortly after the publication of the Third Edition of this book in 2002, Gordon had the misfortune of being diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease.

1

R.J. Mitchell

‘He’s mad about aeroplanes.’ That is what the Hanley High School boys said about their friend, Reg Mitchell. Yet, when Reg was born, the aeroplane had not been invented. There had been many experiments with balloons and gliders as men struggled to launch themselves into the air. In 1783 the first successful manned flight was made over Paris in a Montgolfier hot air balloon, and just over 100 years later a German, Otto Lilienthal, flew in a hang-glider. In England, most Victorians laughed at the idea of a flying machine. They said: ‘If God had meant men to fly he would have given them wings.’ It is all the more surprising that a boy born in such an age would one day design an aircraft able to fly at more than 400 mph.

Reg Mitchell was born on 20 May 1895, at 115 Congleton Road, Butt Lane, Stoke-on-Trent, where his father, Herbert Mitchell, was a headmaster in Longton. Within a few months of his birth the family moved to 87 Chaplin Road, Normacot, near Longton, not far from the centre of Stoke-on-Trent. Later they settled down in nearby Victoria Cottage, a comfortable house well outside the industrial smoke and clatter of the Pottery Towns.

Herbert Mitchell, a Yorkshire man from Holmfirth, had trained as a teacher at York College. After obtaining a headship in Longton, he married Elizabeth Jane, daughter of William Brain, a Master Cooper of Longton. During this time he established printing classes in the Potteries. Soon after moving to Normacot, Herbert Mitchell gave up teaching and became a Master Printer at the firm of Wood, Mitchell & Co. Ltd of Hanley. By hard work and use of his artistic ability he became managing director and eventually the sole owner of the printing works until his death in 1933 at the age of sixty-eight. He played a very active part in Freemasonry and achieved high office in the fraternity.

In the early years of this century, school teachers, and even headmasters, were very poorly paid, so it was probably his high position at Hanley printing works which enabled Herbert Mitchell to live at Victoria Cottage and support his rapidly growing family. Before long there were five children, Hilda the eldest, and then Reg, Eric, Doris and Billy, all born fairly close to each other, so that Mrs Mitchell had her hands full looking after her family and home.

Victoria Cottage in no way resembled a cottage; it was in fact a very pleasant residence, and provided the sort of comfortable surroundings in which the Mitchell children grew up. The house was quite large, with a dining room and drawing room facing the garden. At the back, there was a large kitchen with a black-leaded cooking range and an even larger scullery used for the rougher kind of domestic work. In common with most houses built at that time, Victoria Cottage had both front and back stairs. Mrs Mitchell always kept a maid to assist her with the housework and care of the children, and the back stairs were reserved for the use of the maid. In the Edwardian period, maids were not allowed to retire to bed by way of the carpeted front stairs used by their employers.

The house stood in its own grounds, with a lawn and garden which gave the children plenty of space to romp and play, free from too much adult supervision. Beyond the garden was a coachhouse and stables; but since no coach or horses were kept, these outbuildings were given over to the children for use as playrooms. Mr Mitchell senior was a firm believer in keeping boys out of mischief by providing them with plenty to keep them occupied. He was also very anxious that they should all learn to use their hands. Reg, Eric and Billy were given tools and simple materials, and encouraged to follow their own hobbies and make things for themselves. But whatever task they started it had to be done properly, since their father was a stickler for perfection. Even a menial job, such as sweeping the floor, had to be done thoroughly before it would pass his inspection.

Although their father demanded certain standards of work and behaviour, the Mitchell family enjoyed a happy and secure childhood. Being close to each other in age, there was always someone to play with, and they had the care and devotion of both parents. As so often happens, Mrs Mitchell had a soft spot in her heart for Billy, the youngest. She was a very beautiful woman, adored by all her children, but she also had a very determined streak in her character, a quality inherited by her eldest son.

At the age of eight, Reg Mitchell went to the Queensberry Road Higher Elementary School in Normacot. He had a lively, quick brain, and from an early age he was good at mathematics. His class teacher in this subject was Mr Jolly, a close family friend who lived just across the road from Victoria Cottage. Reg was also inventive and artistic, two gifts which were to play an important part in his career.

A few years ago, Gordon Mitchell received a letter from an ex-pupil at the Queensberry Road School, Beatrice Goulding, saying that she was in the same class as Reg.

Reg was always a very clever boy but we did not realise we had a genius in our class. As we read later about his wonderful achievements, we were so proud that we knew him. It seems dreadful that such a genius should die so young. A lot of us in the school with Reg were angry that more often than not little mention was made of the fact that he spent most of his young days in Normacot.

Beatrice Goulding sadly died in June 1985.

After finishing his elementary education, Reg moved on to the Hanley High School in Old Street, Hanley. Its use as a school ended in 1939 when it was commandeered by the Army. Subsidence damage subsequently condemned it as being unsafe for further use. It was while he was at this school that Reg first showed an interest in what was later to become his life’s work. In late 1908, ‘Colonel’ S.F. Cody became the first man to fly an aeroplane in England, achieving a flight in Farnborough of 496 yards at a height of up to 60 ft, and in the following year the Short brothers established an aircraft factory on the Isle of Sheppey. Reg was so excited by this new and wonderful idea of flying that he and his brother Eric began to make their own model aeroplanes.

The two Mitchell brothers had no kit or printed instructions to follow; they simply made up shapes of their own designs. As their pocket money was restricted to a few coppers a week, they could not afford to buy much. They used fine strips of bamboo cane to make the wings and fuselage and then glued on a layer of paper to ‘keep out the wind’. The parts of the model were held together by a covering of elastic material like stockinette. The propeller, carved out of wood, was turned by a twisted rubber loop. What fun they had as their fragile aircraft swooped and dipped over the lawns at Victoria Cottage.

As well as having a vivid imagination and an easy mastery of mathematics, Reg was also good at games. He was a sturdy, well-built lad, with broad shoulders and, as a capable batsman, he could always be relied upon to get the school cricket team out of trouble and this earned him a good deal of popularity.

At home in Victoria Cottage, there was never a dull moment when Reg was about. He was always inventing something new to amuse his brothers and sisters. He even made a small-sized billiards table, using stretched webbing fabric as cushions, and it gave the boys hours of entertainment. Reg played the game so often that his father, anxious for his son to do well at school, was heard to complain: ‘Reg will never pass his examinations if he spends so much time playing billiards.’ In spite of his father’s gloomy prophecy, he passed all his examinations, taking them in his stride as easily as he fashioned his model aeroplanes. His interest in flying increased when he started to keep racing pigeons and to send them over to France to compete in ‘homing’ races.

Though he sometimes seemed aloof and occupied with his own interests, Reg was always the leader and instigator of every youthful escapade. He was fond of his brothers and sisters, and his affection for his mother made him feel especially protective towards her favourite, young Billy. This was shown in an incident which occurred when Reg was twelve and Billy only a little lad. One evening, when Billy had been put to bed, the rest of the family sat in the room below enjoying a game of cards. Suddenly they heard a terrific bang overhead, followed by Billy’s frightened screams. Reg leapt to his feet and was upstairs in a flash, urged to greater speed by the sight of smoke coming out from under the bedroom door. Without a second’s hesitation he plunged into the smoke-filled room and, gathering up the sobbing little boy in his arms, he carried him out to safety. The gaslight was always left on until Billy was asleep, and on this particular evening a sudden gust of wind from the open window had flung the curtains against the gas mantle and they had immediately gone up in flames. The flames spread to a picture cord, and it had been the banging of the picture as it crashed to the floor which had alerted the family. Reg’s quick reaction probably saved his young brother’s life.

Reg enjoyed his school days, and in his spare time he devoured every scrap of information he could about aeroplanes. In the days when Reg was at school, flying as a mode of travel was only in the experimental stage, and the appearance of any aircraft was likely to make headline news. Reg was not a particularly studious lad – it would seem that he did not have to be from his exam record – he preferred making things to reading books, particularly fiction. He was very persistent. If he set himself a task he would finish it, no matter how boring and tiresome it turned out to be. Once, while still at school, he decided to read the entire works of Sir Walter Scott, though why he chose that particular author, no one knew. Hour after hour he sat on a stool by the kitchen range, ploughing through Ivanhoe, Kenilworth, Rob Roy and the rest, until his self-imposed task was completed. Anyone who has struggled through the duller pages of Scott’s narrative will have some idea how it must have been for a young and very active lad. But this gift of perseverance, of never giving up a task once he had started it, was one of the reasons for his future success as an aircraft designer.

In 1911, at the age of sixteen, Reg left Hanley High School and his father entered him as an apprentice at the locomotive engineering firm of Kerr, Stuart & Co. The works, situated in Fenton in the centre of Stoke-on-Trent, stood between the railway line and the river, and the firm provided a sound basic training in engineering. Reg, however, found this new life not entirely to his liking. All apprentices had to start work in the engine sheds, and this meant that he had to get up very early and travel down to Stoke on the workmen’s tramcar. It wasn’t the early rising that he objected to, but the fact that he had to wear overalls and carry his own lunch, which included the detested tea-can – a white enamel can with a handle and a lid serving as a cup – the sort of thing carried by all workmen at that time. Reg had just left school, where he had been a popular member of the first eleven cricket team, and he simply did not enjoy having to travel into town dressed in his overalls with his tea-can. At night he had to return home with grimy hands and with his overalls plastered with oil and dirt. He began to rebel against this daily ordeal, and when he could stand it no longer he openly protested to his father. But Mitchell senior, who was determined that his son’s training should be practical as well as theoretical, gave him a brief but emphatic reply: ‘You will go, my lad, and you will like it!’

One of his first jobs at Kerr Stuart’s was to make the mid-morning tea for his group of fellow-apprentices and for his foreman. It would seem that Reg and the foreman did not exactly hit it off right from the start. One day not long after he started his apprenticeship, having duly made the tea, Reg gave the foreman his mug, whereupon he took one mouthful and promptly spat it out saying, ‘It tastes like piss!’ Reg said nothing, but thought that if that was what he wanted, he would damn well get it. So next day he went off to the wash-room as usual to fill the kettle with water, but this time instead of tap water, he peed into the kettle. Having boiled it he made the tea and handed the mugs round having first warned his fellow apprentices not to drink any. The foreman took one sip, then another larger one and said, ‘Bloody good mug of tea, Mitchell, why can’t you make it like this every day?’ Honours about even on that episode, it would seem!

When Reg completed his training in the workshops, he moved on to the drawing office. Things now became much better as the hated blue overalls were a thing of the past. During his five-year apprenticeship at Kerr Stuart he attended night school, taking classes in engineering drawing, higher mathematics and mechanics, since he had already decided to make a career in basic engineering. He did so well in mathematics that, while he was attending the Wedgewood Burslem Technical School, he was awarded a special prize, one of three presented by the Midland Counties Union. Also, in 1913, he was awarded the second prize by the Union of Educational Institutions for his success in their examination in Practical Mathematics in the Advanced Stage. For his prize, R.J. selected Applied Mechanics by D.A. Low (1910), a textbook for engineering students.

While he was working at Kerr Stuart, Reg made a lathe which he was allowed to erect in one of the downstairs rooms at Victoria Cottage. Because he was so fond of making things, the lathe was in constant use, and it was Eric’s job to work the treadle with his foot. If he forgot what he was doing and let his foot slow down, he was quickly roused into vigorous action by a storm of protest from Reg.

His father, Herbert, was a very keen chess player and in due course introduced it to Reg, who found it interesting and soon became quite good at it, so that he quite often had a game with his father. The trouble, however, was that Herbert studied each move very carefully and hence took a long time before deciding what his next move should be. In marked contrast, Reg could usually decide on his next move (and that of his father) quite quickly. Understandably, Reg became more and more frustrated by what he considered to be the unnecessarily slow way in which his father played, while at the same time feeling that it would only upset him if he said anything about it!

As his work at Kerr Stuart progressed, Reg constructed a dynamo, making nearly all the parts himself, either at work or on his home-made lathe. A dynamo is not exactly a simple piece of apparatus, and the fact that he could make one entirely by himself showed his early abilities as a designer and engineer. Undoubtedly, these special gifts helped to bring him success later in his life.

Not content with his dynamo, Reg wanted to set up an electric light circuit. Victoria Cottage, like most houses at that time, was lit by gas and Reg was fond of reading in bed. He resented having to drag himself out from under the blankets to put out the gaslight hanging from a central point in the ceiling. To solve the problem he used a simple Leclanche cell battery and connected up the wires via a switch to an electric bulb hanging at the head of the bed. After that it was quite easy to put out the light when he had finished his book.

In all the various things he made, Reg showed an outstanding creative ability. He had tremendous energy and enjoyed hard work. Whatever he was doing, whether working or playing, he did it wholeheartedly. His gift for making things was encouraged by his father, who wanted all his children to develop their own interests.

In 1916, Reg left Kerr Stuart and began to look round for work. He was now twenty-one, and the First World War was in its second year. He made two attempts to join the forces, but each time he was told that his engineering skills would be of more use in civilian life. While he was looking for a job he did some part-time teaching in Fenton Technical School. In 1917, he applied for a job as personal assistant to Hubert Scott-Paine, the owner, at the Supermarine Aviation Works, Woolston, Southampton. One morning soon afterwards he rushed in to see his former teacher, Mr Jolly, waving a letter in his hand.

‘Just look at this!’ he cried. ‘It’s a letter from Supermarines inviting me to go for an interview.’

After a lengthy discussion, Mr Jolly and Reg’s father both agreed that it was a splendid opportunity. Reg was torn in two. He was attracted to the idea of working in an aircraft factory, but was reluctant to move so far from home, particularly because he was then courting Miss Florence Dayson, headmistress of Dresden Infants’ School. In the end he was persuaded to go. A few days later he travelled down to Southampton and so began a lifelong association with Supermarine.

2

Supermarine

All of Mitchell’s work as an aircraft designer was done at the Supermarine factory in Woolston, Southampton. This factory was started in 1912 by a remarkable man named Noel Pemberton-Billing. As a young man he had led an adventurous life in South Africa, and when he returned to England he was caught up in the new craze for ‘flying machines’.

While living on a boat, moored on the River Itchen in Southampton, Pemberton-Billing decided to set up his own aircraft factory. Looking round for a possible site he chose a disused coal wharf at Woolston. This piece of wasteland lay on the east bank of the river, just above the old Floating Bridge which for many years ferried people across the Itchen. As J.D. Scott states in his book, Vickers: A History, published in 1962 by Weidenfeld and Nicolson, who have given their permission to quote from it, Pemberton-Billing coined the name ‘Supermarine’, being the logical opposite of ‘submarine’, since he intended to specialise in machines which would fly over the sea.

The construction work at Woolston attracted the attention of the press. In November 1913 an article appeared in the Southampton Times and Hampshire Express under the heading:

Flying Factory at Itchen Ferry

Workmen are engaged on a stretch of river frontage between the Floating Bridge Hard and the old ferry yard, preparing premises for the construction of Supermarine. There is already on the site one large shed, once used as a coal wharf, which has been converted into an engine building. A second shed, 200 ft by 60 ft, is now being constructed. Cottages in Elm Road, facing the site, are to be altered into offices. The river frontage up to the Floating Bridge Company’s premises has been secured for the building of ‘Water Planes’. Mr Pemberton-Billing, who boasted he would be given a flying certificate after twelve hours flying, actually gained it after three hours. He is the proprietor of the venture, which is expected to be working by Christmas.

In this motley collection of buildings – one shed, a disused coalhouse and a few empty cottages – Pemberton-Billing began to build flying boats. As the name suggests, a flying boat had a boat-like hull which enabled it to operate from water.

Pemberton-Billing’s first flying boat, the PB 1, was a biplane with the pilot’s seat placed well forward in the hull. The factory had a slipway leading into the river, down which the flying boats were launched ready for take-off. The PB 1 was shown at the Aero and Motor Boat Show at Olympia in March 1914, where it aroused considerable interest, but as an aircraft it was not a great success and never flew.

In 1916, Pemberton-Billing disposed of his control of Supermarine, having previously turned it into a limited company. Subsequently it came under the management of Hubert Scott-Paine. Known as ‘Ginger’ because of his bristling red hair, Scott-Paine was a large jolly man with a tremendous enthusiasm for flying. He liked anything that went fast and he had his own motor boat in which he roared up and down Southampton Water.

In 1923, Scott-Paine in turn sold the Supermarine company to a colleague, Sqn Cdr James Bird, who had joined the company in 1919.

The outbreak of war in 1914 had roused Pemberton-Billing into action. He asked his draughtsmen to draw up a machine to be used for reconnaissance work, and he wanted it made quickly. On Monday morning he set his team to work and within a week the PB 9 was designed, built and ready to fly. Nicknamed the ‘Seven Day Bus’ it was used as a trainer with the Royal Naval Air Service for a short period.

One of the Supermarine designs was a little more successful. This was the PB 25, a single-seater scout, twenty of which were ordered by the government.

During the First World War, Britain suffered aerial bombardment from German Zeppelins. A daylight raid over London, which caused much loss of life and destruction, shocked the whole nation. In 1916, in a spirit of retaliation, Pemberton-Billing designed a quadruplane which he imagined hopefully would bring the Zeppelins down in flames. This peculiar-looking aircraft, the Night Hawk, had a top speed of 70 mph, while the faster Zeppelin could do 75 mph. In some ways Night Hawk was in advance of its time, for it carried a searchlight and a 1½-pounder gun, but it failed to be accepted for service.

Pemberton-Billing was deeply concerned about the poor quality of the aircraft used by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). The observer was usually armed with a rifle and a revolver with which he was expected to defend his aircraft. Not surprisingly, the casualty rate was very high.

With the intention of arousing public indignation over the loss of so many young airmen, Pemberton-Billing got himself elected to parliament. In his maiden speech in the House of Commons he violently attacked the government by declaring that the RFC crews were being ‘murdered’ by lack of efficient machines. Fearing that he might be accused of promoting his own interest in the manufacture of aircraft had caused him previously to dispose of his control of Supermarine.

Under the new ownership of Hubert Scott-Paine, the works became known as The Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd. It remained under government control for the rest of the war and continued to build aircraft. They also produced the first British flying boat fighter, the Baby.

This was the state of affairs at Supermarine when Mitchell arrived at Woolston for his interview with Scott-Paine. This proved to be successful. No doubt his quiet manner, combined with an aggressive jaw which gave his face a determined expression, persuaded Scott-Paine to give the eager young man from Stoke-on-Trent a chance. Mitchell was so delighted at the outcome that he did not even consider returning home; he merely wired his father asking for his belongings to be sent down to Southampton.

Mitchell’s first job at Supermarine was acting as personal assistant to Scott-Paine, and in this capacity he soon became familiar with all the work going on in the factory. As we have seen, he had always been interested in flying, and the sight of the flying boats under construction in the sheds excited his interest and introduced thoughts of designing one himself. His practical basic training in engineering stood him in good stead during those first months at Supermarine when he had to make a quick adjustment from locomotives to aeroplanes.

It was not only the work that was new to him; living in Southampton brought Mitchell into fresh surroundings. He was now in his early twenties and all his previous life had been spent in Stoke-on-Trent. There he had grown accustomed to the crowded conditions of an industrial town. Dust and smoke shrouded the Trent Valley, while lines of workers’ cottages sprawled across the surrounding hillsides. The drabness of the scene was enlivened by the cheerful friendliness of the people, and that same kindly concern for others was an integral part of Mitchell’s nature.

Working at Supermarine, Mitchell looked out on a different world. There in front of him was the River Itchen, widening as it flowed into Southampton Water, and over which the seagulls continually dipped and soared, replacing the homing pigeons of his earlier days.

Scott-Paine quickly recognised the capabilities of his new man, and in 1918, at the end of Mitchell’s first year at Supermarine, he made him assistant to the works manager, Mr Leach. Having earned his first promotion, Mitchell decided it was time to marry the girl he had left behind in Staffordshire. It was 1918, and the First World War was not yet over when he paid a hurried visit to his family and told them of his plans. During his brief stay, he and Florence Dayson were married at Meir Church in the village just beyond Normacot. The newly wedded pair returned to Southampton, and for the first months of their marriage they rented a house in Bullar Road, Bitterne Park. To make the journey to Supermarine easier Mitchell bought a motorcycle and sidecar, which was the first vehicle he owned and of which he was extremely proud.

Flo, a girl with thick brown hair and dark eyes, made Mitchell an excellent wife. She shared his love of sport, and over the years she became a very good tennis player. She also had great strength of character and courage, which enabled her to face the loneliness when she had to take second place to Mitchell’s work. With him, work was always of major importance, and when he was concentrating on a particular task everything else was forgotten and time was of no importance. But fortunately for Mitchell, Flo understood the ambitions of the man she had married, and was always there, waiting at home, ready to look after him and entertain his friends.

Mitchell was never a good correspondent and hated writing letters. However, he did send one to his brother Eric, who had missed the Meir wedding because he was serving with the British Army stationed in Egypt:

1 October 1918

Dear Eric,

Thank you very much for your letter of 19 August. I like your remarks about my making a page in history, young fellow! Flo joins me in thanking you for your kind wishes, and we must congratulate you on promotion to corporal. We feel quite proud of having a real live corporal in the family.

The war news has been exceedingly good around your quarter of the globe lately, and we are looking forward to seeing you on Southampton quay before so very long.

I am still very busy and have little spare time. We are building Short seaplanes now, and are turning out about six a month. We have got to increase this to nine a month before Christmas, so we shall have plenty to do. I suppose your weather is now at its best. We have had nothing but rain lately. Everyone is busy saving match stalks and cinders to supplement the coal ration!

Flo wishes me to say that you must address your letter to both of us when you write, and don’t let the interval be so long this time.

Very affectionately,

Yours,

Reg

Working with seaplanes and flying boats gave Mitchell great satisfaction, because it gave him a chance to use his creative ability. When faced with a problem, he would stick at it until he found the answer. He had an intuitive eye for a good design and he could usually tell merely from looking at a drawing whether it had possibilities. His competence in mathematics was a great help and enabled him to calculate such complicated factors as the stresses in aircraft structures. As J.D. Scott comments, his mind lived with the shapes that would move most effectively through the air. His intuitive understanding of aerodynamic problems impressed most deeply those whose formal training in aerodynamics had gone much further than his own.

But his devotion to work did not prevent Mitchell enjoying himself in his spare time. Being strong and well-built, he played games with the same energetic enthusiasm he showed for work. He and his wife joined the Woolston Tennis Club and soon became amongst the leading players. At the opening of one season, Mitchell and Lady Apsley played a demonstration match against Lord Apsley and his partner. Lord Apsley was MP for the Itchen division of Southampton.

Mitchell was a handsome man. His most striking feature, and the one which attracted everyone’s attention, was his fair blond hair, the sort of colour seen on pictures of Plantagenet kings. He had bright, cornflower-blue eyes and a magical smile, of which not everyone received the benefit! Local people in Woolston soon began to recognise him in the streets, and he would sometimes give ladies from the tennis club a lift in the car which by now had replaced his old motorcycle and sidecar.

When Mitchell became assistant works manager in 1918, the Supermarine factory had altered very little from Pemberton-Billing’s days. It was still a small firm, its premises consisting of one large hangar where the aircraft were built and smaller buildings on either side used as boat-building sheds and offices. The design team was limited to six draughtsmen and a secretary, and, since there was no money to spare, everything had to be done on a shoestring. But there was a very friendly atmosphere. Any apprentice lending a hand at launching time might be offered a free flight. At such times the lad merely turned his cap back to front and climbed in. Even the girl secretary enjoyed a quick flip round the Isle of Wight.