Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

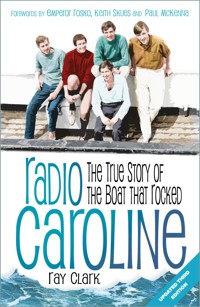

Radio Caroline was the world's most famous pirate radio station during its heyday in the 1960s and '70s, but did the thousands of people tuning in realise just what battles went on behind the scenes? Financed by respected city money men, this is a story of human endeavour and risk, international politics, business success and financial failures. A story of innovation, technical challenges, changing attitudes, unimaginable battles with nature, disasters, frustrations, challenging authority and the promotion of love and peace while, at times, harmony was far from evident behind the scenes. For one person to tell the full Radio Caroline story is impossible, but there are many who have been involved over the years whose memories and experiences bring this modern day adventure story of fighting overwhelming odds to life. Featuring many rare photographs and unpublished interviews with the 'pirates' who were there, Ray Clark, once a Radio Caroline disc jockey himself, tells the captivating story of the boat that rocked!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 562

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published, 2013

First published in paperback, 2019

This revised third edition first published, 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Ray Clark, 2013, 2019, 2024

The right of Ray Clark to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75095 473 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

To my wife, Shelley, for having to share her life,for too much of the time, with this other woman – Caroline.

CONTENTS

Forewords

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Introduction

1. Before Caroline

2. Project Atlanta

3. The ‘Why Not’ Business

4. Chug-a-lug, Chug-a-lug, Chug-a-lug

5. Genius

6. Your All-Day Music Station

7. The Ship that Rocks the Ocean

8. The Caroline Network

9. You’re Hearing Things …

10. Bringing News to the Nation, Fast and Factual

11. The Tower of Power

12. A Sudden Swing in High Command

13. Mayday, Mayday

14. It’s a Cash Casino

15. The Sound of the Nation

16. Oh, Mister Benn, You’re a Young Man

17. Let Me Marry You …

18. Paying for Plays

19. The Fight for Free Radio

20. Caroline Continues

21. Cutting the Chain

22. Television, Who Do You Think You Are Kidding … ?

23. Unseaworthy and Barely Habitable

24. Caroline Comes Home

25. Ship in Distress

26. We’ll Be Back

27. Eurosiege

28. Into Overdrive and Playing the Hits

29. Hurricane Force 12

30. Who Are the Real Pirates Here?

31. Could this Finally Be the End?

32. What Do We Do Now?

33. Past, Present … Future?

34. Speculation, Maybe & Hearsay

FOREWORDS

Emperor Rosko

I was utterly shocked and pleased that I was selected to say a few choice words to open this collection of pirate radio information, lovingly put together by my man Ray. We go back quite a long way and he had dozens who he could have asked.

All DJ foolishness aside, Ray knows more than enough to handle and coordinate the info on Radio Caroline (although he doesn’t know about my night with a French journalist on board, but that is probably for the better, as she had wanted a real taste of pirate life …)

Enjoy the read and keep the Jolly Roger flying!

Emperor Rosko, EMP, 2013

Keith Skues

My ambition as a schoolboy was to work for the BBC. However, having worked for eighteen months on Radio Caroline I wanted to see the introduction of commercial radio into Britain – and I wanted to be a part of it. Fortunately I was lucky on both counts.

Radio Caroline was the centre of attraction in the Swinging Sixties and the first station that pop stars of the day would turn to in having their records played. Listeners loved the music and the DJs.

In turn Caroline helped to bring about the deregulation of British radio with BBC Radio 1 and BBC local radio in the 1960s. A number of offshore DJs joined Radio 1 in 1967.

We had to wait until the 1970s for the introduction of independent (commercial) radio. Now listeners have a huge choice of stations to which they can listen.

Never in my wildest dreams would I have envisaged we would still be talking about ‘pirate’ radio fifty years later.

Thank you Radio Caroline for helping me to achieve my ambition.

Keith Skues, 2013

Paul McKenna

I can’t overstate how amazing it feels to open the mic and know that you are broadcasting on Radio Caroline. The magic is still there. It feels like coming home.

Over the years, many pirate radio stations have come and gone. I believe one of the factors in them going, as good as they were, was because they were essentially just businesses whereas Radio Caroline is a movement based on freedom.

This wonderful book by Ray Clark captures the drama, excitement and magic of the amazing real life adventures of one of most loved parts of modern pop history. I really hope you enjoy reading about this most wonderful radio station and the extraordinary people who make it what it is.

Paul McKenna, 2019

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Ten years on from the original publication, this third edition contains yet more memories from the incredible, and often unbelievable, story of Radio Caroline. My grateful thanks go to everyone who has contributed to this book with interviews, photographs, and information.

Very special thanks go to Colin Nicol for allowing me access to transcriptions of his interviews, made many years ago, with the key players from the early days of British offshore radio, and Radio Atlanta in particular. Without Colin’s foresight, a very important part of British radio history would have been lost.

Chris Edwards and François L’hote from Offshore Echos Magazine continue to provide invaluable help and encouragement, as has Jon Myer from the ‘Pirate Radio Hall of Fame’. Thanks are also due to veteran radio engineer George Saunders.

Special thanks to Nigel Harris and Andy Archer for the use of extracts from their fine books; to my friends, Bill Rollins, Hans van Dijk and Pete MacFarlane for encouraging my unhealthy interest in this topic and forcing me into a reasonably successful radio career; to my radio friends who are still prepared to answer my questions years after the event and get excited about the topic, even if, to the rest of the world, they appear to be quite normal; to those who have bought previous editions of my book and have told me how much they’ve enjoyed reading the story or have written kind reviews; and to the team at The History Press, especially Chrissy McMorris for her patience … and for always finding that extra little bit of space for a few more words.

For her extreme patience and understanding of punctuation and knowing how to spell big words, my love goes to my wife, Shelley.

The following websites are essential browsing for anyone wanting even more information on the fascinating topic of offshore radio:

www.offshoreechos.com

www.offshoreradio.co.uk

www.offshoreradiomuseum.co.uk

www.offshoreradio.info

www.hansknot.com

www.radiocaroline.co.uk

www.radiolondon.co.uk

www.rayradio.co.uk

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ray Clark has enjoyed a successful radio career for more than thirty years, after fulfilling his dream of working aboard Radio Caroline in the Eighties. Since then he has regularly broadcast on a variety of commercial and BBC radio stations, together with frequent appearances on Pittsburgh’s KDKA, the world’s oldest radio station. He has won numerous prestigious national and international radio awards.

Ray continues to present programmes on Radio Caroline and BBC and has also written The Great British Woodstock: The Incredible Story of the Weeley Festival 1971 (The History Press) and Stay Tuned – I Could Say Something Brilliant at any Moment ! (Poppublishing). Both available via radiobookoffer.co.uk.

INTRODUCTION

It’s strange now to think back to the days of Radio Caroline when a large proportion of the British population were listening to a ‘pirate’ radio station, either Caroline or one of the others that followed her lead. Millions tuned in daily to disc jockeys who soon became household names, broadcasting from ships and marine structures off the coast, playing the pop hits of the day and urging us to buy everyday products that we all knew from the tuneful advertising jingles that we heard hourly.

Radio Caroline, is that still going?

Well, yes, and thriving. Although its audience is just a few thousand nowadays, rather than millions, it has survived. This is the amazing story of ‘The Boat that Still Rocks’ – Radio Caroline.

***

Those of a similar age to me will have grown up with memories of listening to Radio Caroline, either through the swinging Sixties, the psychedelic Seventies or the ‘loadsa money’ Eighties. The music and those playing it – and the conditions that they worked under – certainly made an impression at the time.

My life has been influenced by much of what I’ve heard on the radio: the music, the fun and what Caroline stood for.

Radio Caroline lit that spark in my imagination from the first time I heard it, Easter 1964. Since then I have followed her ups and downs and stayed loyal – for most of the time. There have been times when Caroline sounded so amazingly good that I found it difficult to turn the radio off; occasionally it was so bad that I only listened because it WAS Caroline.

Radio Caroline was the world’s most famous pirate radio station, but did the millions of us tuning in realise just what battles went on behind the scenes? Financed originally by respected city money men, this is a story of human endeavour and risk, international politics, business success and financial failures. A story of innovation, technical challenges, changing attitudes, unimaginable battles with nature, disasters, frustrations, challenging authority and the promotion of love and peace while, at times, harmony was far from evident behind the scenes.

For one person to tell the full Radio Caroline story would be impossible but in the pages that follow you will read the inside story of much that happened during Caroline’s days at sea and since she came ashore, including previously unpublished interviews with the ‘pirates’ who were there and featuring many rare photographs. Of course there is plenty that will never be written … there were just so many adventurous, funny, frightening, happy, sad, dangerous, ridiculous, stupid, frustrating and unbelievable events that will be remembered only by those who were involved at the time. I’ve been lucky enough to have heard many of these stories from those who were there.

The aim of this book is to put on record a very special time that was enjoyed by so many people. It tells the story of a battle between those wanting to challenge and provide an alternative to a heavily regulated system of radio, those just wanting to be involved in something different, determined businessmen and equally determined politicians.

This is the captivating story of the boat that really did rock – a story that will never be repeated, but deserves to be recorded for the future. Radio Caroline is an important part of radio history and the role it played should be acknowledged and remembered … it’s also a story that I am proud to have played a tiny part in.

***

This is Radio Caroline on 199, your all-day music station. We are on the air every day, from six in the morning till six at night. The time right now is one minute past twelve and that means it’s time for Christopher Moore.

Hello and happy Easter to all of you. This is Christopher Moore with the first record programme on Radio Caroline. The first record is by the Rolling Stones and I’d like to play it for all of the people who helped to put the station on the air, and particularly for Ronan.

Noon on Easter Saturday, 28 March 1964 and Radio Caroline was on the air. Broadcasting from a ship named Caroline which was registered in Panama, owned by a Liechtenstein company called Alruane and hired by Planet Productions – an organisation that was registered in Ireland and benefitted from the business of Planet Sales, which would sell advertising on Britain’s first commercial radio station. A complex, and purposely confusing pathway of internationally based operating companies was behind her, but this first broadcast started a radio legacy that continues to this day.

The ship anchored just beyond British territorial waters, north-east of Felixstowe at around 6.30 p.m. on Good Friday 1964. With a towering 168ft high steel transmitting mast, generators powering away to supply the studio equipment and the two American built 10 kilowatt transmitters, test broadcasts started just a few hours later.

On board were the Dutch skipper, Captain Baeker, and his marine crew, Swedish radio engineer Ove Sjöström and two broadcasters, 23-year-old Christopher Moore and Simon Dee, then aged 29. Neither had presented a radio programme before, but it would be their job to make continuity announcements and present occasional live record sessions between pre-recorded programme tapes of popular music.

1

BEFORE CAROLINE

Before Radio Caroline’s first broadcast, radio in Britain was provided by the BBC, and though not controlled by the Government, they did regulate it. Its purpose, as set out by the first Director General, Lord Reith, was to educate, inform and entertain; however, it seemed to concentrate more on the first two objectives and less on the latter. Although British pop music was taking the world by storm in the early Sixties, you could hear very little of it on the BBC.

Radio Luxembourg was the only place for pop music fans to hear the hits of the day. Broadcasting from mainland Europe, English-speaking announcers played pop music and commercials every evening. But the signal was poor; it faded in and out continually, it couldn’t be heard in the UK during daylight hours and the programme content was dictated by the major record companies, who bought airtime to promote their own recordings.

Unlike the USA and Australia, Europe had very few commercial radio stations, other than those based in Luxembourg, Monte Carlo and Andorra. In most countries, the state-regulated national broadcasting and European governments saw no need for change. The only way to provide an independent radio station was to operate outside state boundaries and outside the law, selling commercials to finance the broadcasts.

The first commercial radio station playing popular music to a mass market and operating from a ship in international waters started in August 1958, when Radio Mercur (Mercury) came on the air. Listeners in Denmark were able to tune in to broadcasts from homemade equipment aboard a tiny ship, the Cheeta, moored off the Danish coast. The idea came after Peer Jansen, the founder of Radio Mercur, heard about the US Government-backed Voice of America radio station which was broadcasting from a ship anchored off the coast. The MV Courier was moored in the Mediterranean while transmitting programmes that promoted an American view of the world to listeners in Communist countries in the area, such as Albania.

Jansen and his team studied the broadcasting laws and found a way to broadcast legally … or at least, not illegally. The Danish press called them radio pirates, but Radio Mercur, in various forms, remained on air until 1962, when broadcasts to Denmark were outlawed by the introduction of new laws.

The success of the station had not gone unnoticed; other groups became involved with Radio Mercur and, at various times, three different ships associated with the station were broadcasting off the country’s coast.

The next offshore radio venture was a far more professional set up from the start. Jack Kotshack lived in Sweden and, through his contacts, met a Texan, Gordon McLendon, who was visiting the country on business. He owned several radio stations in America including KLIF in Dallas and KILT Houston, both market leaders. McLendon understood commercial radio and was one of America’s major players in the business.

Within hours of meeting, McLendon and Kotshack agreed that they should start a radio station similar to Radio Mercur, but aimed at a Swedish audience. It was to be known as Radio Nord and it would be financed by Texan money men. A maximum budget of $400,000 was agreed and, at the start of 1960, the team went looking for a suitable ship. They found a small coaster called the Olga moored in Kiel, Germany.

I think she was one of the ugliest boats I have ever seen. Small and worn, she lay on the dock, surrounded by an overpowering stench of rotting herring, noticeable 20 metres away.

Jack Kotshack, The Radio Nord Story (Impulse Books, 1970)

The Olga, originally called the Margarethe, had been built in 1921 as a steel schooner weighing just 250 tons. Over the years she’d been lengthened and fitted with a low-powered diesel engine and had already had a hard life, surviving five years of coastal work during the war.

On 31 May 1960, she was towed to Hamburg, where she underwent a major refit. The cargo hold was converted into cabins for the crew, with space allocated for transmitters and the generators needed to power a radio station. A new superstructure was built, containing the galley, the messroom and broadcast studios. However, final preparations for her conversion came to a halt when the shipyard was notified that it was illegal under a pre-war German law to install or repair a radio station without government permission. The ship was taken to Denmark for further work, then Finland and, finally, made broadcast-ready once anchored off the Swedish coast.

The Olga was renamed Bon Jour and became the home of Radio Nord. Many issues delayed the start of the radio station, but once these problems, political and technical, were overcome, the station broadcast successfully off the coast of Sweden for fifteen months, from March 1961 until the close down on 30 June 1962, one month ahead of new laws introduced to outlaw offshore broadcasts to Sweden.

The days of Radio Nord were over, but the American investors still owned the small radio ship housing a complete radio station, able to go anywhere in the world. The immediate future of the ship became uncertain, but she would play a huge part in the story of Radio Caroline in the years that followed.

In April 1960, Radio Veronica had started broadcasts off the Dutch coast. Despite a precarious start, Veronica went on to broadcast successfully from sea until 1974 and later to have a role in the Dutch national broadcast system.

The Dutch VRON (Free Radio Broadcasting Netherlands) was set up by a consortium of Amsterdam businessmen. Dubious financial dealings preceded the first broadcasts of Radio Veronica, but eventually a former German lightship, the Borkham Riff, registered in Guatemala was equipped and moored off the Dutch coast. Programmes were recorded on land and played from the ship and, although the audience grew quickly, little money was made in return. Six months after coming on air three brothers, the Verweijs took complete control of the venture – one of the brothers, Bull, was part of the original group of investors.

Veronica’s new owners were keen to increase their income and decided to target a British audience, so CNBC (the Commercial Neutral Broadcasting Company) was set up. Three English-speaking broadcasters were hired, including Paul Hollingdale, an Englishman who had experience with the British Forces Broadcasting Network, who was given the role of programme director.

All programmes, which consist of pop records and advertising material are taped in a studio at Hilversum and then taken out to the ship …

The Stage and Television Today, 23 February 1961

There were only three people involved with CNBC: Doug Stanley, a Canadian Broadcaster, John Michael, a Canadian and me. The people behind the station were three Dutch brothers, they worked in the textile business in Hilversum, making a fortune manufacturing and selling nylon stockings.

Paul Hollingdale, DJ

You’re listening to the radio sound of tomorrow today, the CNBC way. If you dial 192 metres medium wave, you get us. We hope you do, as of this morning this is CNBC broadcasting to the south-east coast of England and other parts, no doubt, of England picking us up. We’d like to hear from you by way of reception reports to find out what it’s coming in like.

The show consisted of popular music, a mix between 208 [Luxembourg] and the Light Programme [BBC]. We broadcast until lunchtime with the programmes of Radio Veronica starting after that. All of our shows were recorded in studios that we constructed within the textile factory located in Hilversum. The tapes were then taken aboard the ship for transmission. CNBC had a London office, located in a newly built block called Royalty House in Dean Street.

Paul Hollingdale, DJ

The CNBC programmes quickly gained listeners in the south-east of England and East Anglia and questions about the broadcasts were asked in Parliament. But politics played no part in the demise of CNBC; the signal just wasn’t strong enough, leading to poor reception and interference.

CNBC closed down because the medium-wave signal on 192 metres was too weak to penetrate into London. The project failed when an engineer hired by the Verweij brothers received money from them to buy a more powerful transmitter, but he spent the lot in London on the fast life with women, one of whom became pregnant. We were denied the opportunity of this transmitter and the station closed down.

Paul Hollingdale, DJ

‘PIRATES OUT’

Radio Veronica, the pirate radio which has been beaming a commercial radio programme to England from a ship moored off the Dutch coast, is now discontinuing its transmissions. The company have found that their signal is too weak for satisfactory reception over here.

The Stage, 23 March 1961

Next came the unlikely named ‘Voice of Slough’, with plans for Radio LN (London) or GBLN. The intended vessel for this project was a 70-ton fishing boat called the Ellen. She was moored in Leith harbour in Scotland and had been detained in port, because she was considered unseaworthy.

The boat set sail on 3 October 1961, under cover of darkness, but didn’t get far; the next day she was towed into North Berwick with engine trouble. After repairs she made off again, only to put into Dunbar with further problems. The man behind the plan was John Thompson, a journalist working in Slough who intended broadcasting from a position off Southend-on-Sea in Essex. As with CNBC, the radio station was to pre-record programmes on land, some reports suggested Ireland, and then broadcast them from the ship. Thompson told reporters that the plan was to collect a transmitter that was hidden near an East Coast creek, ‘a secret rendezvous has been arranged’, although he later said he was still looking for a transmitter; he told the Southend Standard that Marconi had refused to sell him one, so his company may well buy American.

Thompson’s technical advisor and major financier was a Canadian millionaire, Arnold Swanson, who soon decided to break away from Thompson and launch his own radio station, to be called GBOK (Great Britain, OK!). It seems there was little goodwill between the two after the split. According to John Thompson in the Sunday Telegraph on 4 March 1962:

This man Swanson has pinched our idea, his station GBOK is a complete copy of our Voice of Slough idea. You can take it from me that our station, GBLN, will be beaming before his.

The National Archives, HO 255 601

Thompson was true to his word; a broadcast was heard on 306 metres between 4.15 p.m. and 5.30 p.m. on 5 April 1962. The authorities believed it may have come from Mr Thompson’s studio, based in a caravan parked in a builder’s yard in Slough; it certainly wasn’t from his boat which was still in Scotland, beached in Musselborough.

You are listening to Radio Ellen, the Voice of Slough, coming to you from a ship anchored off the Nore.

The National Archives, HO 255 601

It’s not known if the boat ever managed to get to the Thames, but Radio LN, Radio Ellen or GBLN was never heard of again. Thompson later told reporters that he had relinquished control of his company and all ‘intangible’ assets, including advertising contracts, had been handed over to his rival, Arnold Swanson, who had a ship that he planned to use for his station GBOK. The Lady Dixon was an 84-year-old former lightship, weighing 570 tons and lying in a mud berth in a creek off the Thames at Pitsea.

The plans for GBOK were impressive; a colour brochure gave detailed programme information and advertising rates. Programmes for future broadcast were recorded in a specially constructed studio at Swanson’s home in Oxfordshire. He claimed to have invested £80,000 in the project and had already sold £100,000 worth of advertising through his company, the Adanac Broadcasting Agency.

Post Office officials, who were responsible for regulating broadcasts in Britain, had little detail of the proposed radio station in the early months of 1962, but they did suspect that a lightship would be used and set about looking for it. They initially failed to track down the Lady Dixon, but inadvertently they stumbled across what may have been a future offshore radio project without realising what they’d found.

An official report gave details of a boat called Satellite,* a lightship tender, that had been sold by Trinity House during 1961 and was registered to Mr Allan James Crawford, the owner of a group of music publishing companies. The Satellite was moored in East Cowes though no link was found to the GBOK project and no more was heard of the Satellite. Mr Crawford would certainly come to the authorities’ attention during the months that followed.

As 1962 progressed, plans for GBOK continued, but there were problems when tugs tried to pull the Lady Dixon free from its muddy berth in Pitsea Creek. Several attempts were made and eventually three tugs managed to free the hulk and tow her across the Thames to Sheerness, where she was to be fitted out. Press reports suggested that the ship, registered in Liberia, would be on the air within about a fortnight.

As work took place on the ship, Post Office officials observed progress and planned to board her to inspect any radio equipment once it was installed.* But by July 1962 Mr Swanson had given up with the Lady Dixon, saying she would never be sufficiently sound for the project and he was now looking at using another ship, a ‘tank landing ship’, that he would name the Notley Galleon (his home was Notley Abbey in Thame, Oxfordshire). Whether through lack of finance or official pressure, GBOK, just like GBLN, failed to materialise. By August, the Lady Dixon was still moored at Sheerness and the Ellen was somewhere between Scotland and Southend-on-Sea, but a third ship was in the Thames Estuary and, unlike the other vessels, she was certainly capable of fulfilling her role as a broadcasting base.

______________

* The National Archives, HO 255 600.

* The National Archives, HO 255 601.

2

PROJECT ATLANTA

Australian Allan Crawford was a music publisher living in London. He’d been employed by Southern Music, one of the biggest publishing houses in the world at a time when sheet music sales were all important, but times were changing and the music business had become more dependent on sales of the new 45rpm records. In 1959, Crawford decided to ‘go it alone’, setting up his own Merit Music Publishing Company and, later, a variety of record labels, including Rocket, Cannon and Crossbow which featured cover versions of top pop hits of the day, performed by session musicians and singers and available by mail order. He also released original recordings on his Sabre and Carnival labels.

I was managing director of Southern Music both in Australia and in London; I resigned from the London Company after fourteen years to become independent. Then it hit me that having 300 publishers in London striving to get into any half-hour recorded programme on the BBC or Luxembourg was idiocy; there was no way to win as an independent. The publishers that were getting success were the well-established, wealthy publishers, who could wine and dine people and influence them.

I read an announcement that Radio Luxembourg had made an arrangement with one of the big publishers to form a publishing company between them. Well, I was angry at that, because I could see that favouritism was going on. The main advertisers on Luxembourg for the principal hours in the evening were EMI and Decca, so naturally it was their numbers that were being played, and, of course, the disc jockeys employed by Radio Luxembourg, by great coincidence, turned out to be the same ones the BBC were using and were they going to cut off their own bread and butter by not playing the records that EMI and Decca wanted? Of course they weren’t, they’d have been crazy if they had. It was a very restrictive set-up.

I was annoyed so I wrote a sarcastic letter to the BBC and said, ‘Following the announcement in the paper,’ and I didn’t name the article or what it said, ‘I now make the following suggestion: that the BBC and my company, Merit Music, form a sub-publishing company, so that by careful programming, we can do away with such worthy institutions as the Performing Rights Society, the Publishers Association and Phonographic Performance Limited, so that all the numbers being broadcast would belong to Merit Music and the BBC.’

I meant it to be sarcastic, such a thing could never happen. But, you know, they had a fellow ring up, ‘Mr Crawford, we have your letter – what does it mean?’ I’ve forgotten the name of the man but I was invited to lunch with the BBC, in the boardroom, there was a butler serving on silver platters a beautiful luncheon and we were sitting at a boardroom table a mile long and there were only three of us.

One of the men, I think he was in charge of BBC programmes, was reluctant and a little bit huffy at having been made to come, until he listened to what I was saying and he warmed up as I was explaining how Luxembourg worked.

He wrote out the address of a committee* that was meeting to take evidence about the future of radio and he described how they were going to have housewives on this committee and I thought ‘my God, we’re going to get some sense out of this, aren’t we?’ [sarcastically]. He said, ‘would you please repeat what you said to them,’ and I said, ‘I’ll think about it’.

As I left, I stood outside in Portland Place looking up at the BBC building, I said to myself, ‘I’ll be dammed if I’ll do this. I’m not going to play your game to make [the name of] Radio Luxembourg black so that there’ll never be commercial radio in England. I will do it myself.’

And that was that day that pirate radio was born.

Allan Crawford, in an interview with Colin Nicol

Before his meeting at the BBC, Crawford was already aware of radio broadcasts from ships off the coast, in particular the Dutch Radio Veronica and the English CNBC service.

Both Doug Stanley and I came to know Allan Crawford while we were with CNBC. We met on several occasions and he could see the value of pirate radio to break the BBC monopoly. He became aware of the debacle concerning the Verweijs problem, the absconding of thousands of guilders by the rogue engineer they had contracted to buy a powerful AM transmitter from RCA in the US. Allan’s thoughts towards Radio Atlanta occurred shortly after CNBC closed down in 1961.

Paul Hollingdale, DJ

Another of Crawford’s acquaintances was a theatre literary agent called Dorothy ‘Kitty’ Black, she sold plays, he sold music, their business interests were similar and they obviously moved in the same circles.

Kitty Black had been aware of Radio Mercur when she’d been on holiday in Sweden in the late 1950s, so she already knew about offshore radio. She was to play a major role in Crawford’s future plans for commercial radio in the UK.

I was introduced to an Australian called Allan Crawford. I asked him to come and see this musical and because we were both ‘beastly colonials’ – I come from South Africa, he from Australia – we clicked and became great friends and seemed to have the same sort of ideas about most things. One day, Allan told me that he had been approached by the stocking manufacturers who owned the pirate ship called Radio Veronica and they were prepared to sell a half share for something like £60,000. Allan had been over to see the ship and came to the conclusion that for £100,000 it would be possible to buy a ship, install the radio equipment and start our own operation in this country.

Kitty Black, in an interview with Colin Nicol

There was certainly contact between Crawford and Veronica, though any proposed deal was probably more complex than Kitty Black remembered, or was aware of.

I had gone to meet the people in the Dutch ship, the Verweij brothers, and I took a great liking to them. They needed money very heavily in 1961 because they’d struck opposition from the authorities, people were afraid to advertise. I found a small English bank willing to listen and I took them [the bank] over there. The day was such a nice day and the English were so bloody light-hearted, they started to get flippant. The Dutchmen didn’t like it, I mean they were in trouble, they wanted money and they weren’t interested in anyone getting flippant on a nice summer’s day. We came back to England with them not having reached a decision, and it’s always bad not to clinch a thing on the spot. But within days, one of the biggest advertisers had some kind of adverse thing against one of their products and they needed a quick way to offset this unfavourable publicity. They choose to advertise on Veronica and, overnight, they were making 2,000 a week instead of a loss. Now they didn’t need us.

Allan Crawford

With Allan Crawford aware of Veronica’s situation and the costs involved, he searched for investors prepared to put money into his own radio station. His plan was ‘Project Atlanta’, a radio station to broadcast off the English coast. It was, potentially, a very risky business, but also one that could become extremely profitable.

There was no way that I would embark on something unless we had sufficient capital to operate for a minimum of three months. So the sums were gone into over and over again; the cost of the ship, the cost of the equipment, the weekly running costs, the transport between shore and ship, the cost of recording the tapes, the cost of an onshore office – everything that you can think of had been calculated. The problem was always to persuade the backers to put up the money that we needed. Somebody would put up ten thousand, somebody else would then say they would put up another five thousand and then we go to somebody else who said they would put up another ten thousand, so we had twenty five thousand. But by this time, the person who had said that he was going to put up the initial ten thousand had changed his mind, so we were back to fifteen thousand. This was the appalling situation that we were in, neither of us had the kind of financial connections that were needed for this sort of operation, but at this point Allan met up with a very interesting man called Oliver Smedley. He’d stood for Parliament as a Liberal candidate and had great financial ideas as to how things should be operated, he was very go-ahead, very open to new ideas and he became fired with enthusiasm for the pirate radio ship operation.

Kitty Black

When Project Atlanta Ltd was registered on 30 July 1963, the company attracted more than 150 investors, some owning just twenty shares, but others owning considerably more. The largest shareholder was CBC (Plays) Ltd, a company registered in April 1960 to act as agents and managers, Crawford and Black were both directors of this company.

Allan Crawford studied the legalities very carefully, guided by the experiences and research of previous ventures and further legal advice. It’s likely that he had access to papers from the CNBC venture operated from Royalty House, just a few yards away from his own Merit Music office in London’s Dean Street.

The ship would be owned by a Panamanian company. It would be run by a company in Liechtenstein which would enter into agreements with us to sell advertising time in England, which legally we could do. In other words, we had a company that didn’t own the ship but did have a contract with the owner to sell advertising time. The crew would be paid from Liechtenstein, the company that employed the disc jockeys would get so much every month from Liechtenstein and the company selling the advertising would be Project Atlanta Ltd. My lawyers went to the Treasury for permission for the money to go overseas, and the Treasury people said, ‘Yes, this is absolutely above board. It conforms to all English law. You can do it’. From that moment, we knew that we could go and get money legitimately from people to invest.

Allan Crawford

Every time you went round to see somebody to ask if they would put up money for our project you had to explain what you were doing. You were going to buy a ship, anchor it outside the 3-mile limit and you needed two flags of convenience. If the first one was challenged you always had the second in the locker which was your secret flag, all of which cost money. When we met anybody who showed any signs of putting up any money they obviously needed to be given chapter and verse as to how the operation was completely legal, but we were laying ourselves wide open to having all our ideas pirated.

Kitty Black

Crawford needed a ship and his search for a suitable vessel took him to Sweden, where, after a faltering start, the American-financed Radio Nord was proving to be very successful. It was one of three offshore radio stations operating off the coast of Sweden and Denmark: Radio Syd (south) and DCR (Danmarks Commercielle Radio) were the two more recent additions to the offshore fleet. The Swedish Government was in the process of introducing new laws that would make operating the stations illegal and the Americans behind Radio Nord wanted to withdraw from their nautical radio business with as little financial loss as possible. The sale of a complete radio broadcasting station on a ship, together with the equipment from the onshore studios would certainly look good on their balance sheets, and Allan Crawford and his Atlanta project looked a likely buyer.

My attention was drawn to the fact that Radio Nord was operating in the Baltic off Stockholm. I ended up meeting the owners, who were Americans, Texans, and very nice people. Then the ship came up for sale, they were closing down business because of suppressive Government acts and I could see that there was an opportunity.

Allan Crawford

The law to close Radio Nord was passed in May 1962 and came into effect on 1 August 1962, but the company chose to close down a month earlier, at midnight, 30 June 1962. The man running Radio Nord, Jack Kotshack, and his American backers were hopeful of a deal:

At the time, it seemed as if we were in the final stages of negotiations with an Australian businessman, Allan Crawford and his consortium Project Atlanta Ltd. He planned to start a radio station in international waters outside the Thames Estuary, the station was expected to reach an audience of millions of radio listeners in the London area. Allan’s intention was to use his radio station to promote his record label operations, and Radio Nord’s vacant broadcasting ship was offered to him on 4 July 1962, four days after Radio Nord’s closing. She left her anchorage with a newly recruited Polish crew on board, to take her out of the Baltic Sea. In recent months the MV Bon Jour had been re-registered as MV Magda Maria. On board was all the studio equipment, the equipment used in the studios in Stockholm and the entire gramophone library. All the commercial value of the company was in the ship and its cargo and the owners were concerned about any intervention from the authorities on her passage through the narrow strait between Denmark and Sweden, but the ship had an easy trip to the North Sea.

Jack Kotshack, in an interview with Ingemar Lindqvist

In various interviews Jack Kotshack suggests the name ‘Atlanta’ was chosen by US radio man, Gordon McLendon, advisor to Radio Nord, as a tribute to the Texan city that was his home, but Allan Crawford always denied this. Kotshack, in his story of Radio Nord, written after the station’s closure, also referred to Project Atlanta’s original idea of equipping their ship called SS Atlanta. Could this have been the former lightship tender Satellite, that the British authorities discovered while searching for the GBOK ship some months earlier, registered to Crawford and moored at East Cowes on the Isle of Wight?

While negotiations continued between Project Atlanta and Radio Nord’s owners, British government departments had taken the unusual step of talking to each other and sharing information, a trend that, had it continued, may have seriously threatened the future of offshore radio. The Postmaster General was informed by an internal memo of ‘a disquieting development’. The same document shows that plans for Radio Atlanta were at an advanced stage as early as summer of 1962.

In August we received from the treasury a copy of a proposed agreement between a British company CBC (Plays) Ltd and a Liechtenstein registered company, Atlantic Broadcasting Services Establishment. The latter proposes to lease the ship Magda Maria, anchor it outside UK waters and broadcast commercial programmes to the UK. CBC (Plays) Ltd will acquire under the agreement the rights to sell advertising time in the programmes.

The National Archives, HO 255 602

The exact movements of the Magda Maria over the next eighteen months would tell a fascinating story. She took a month to travel from the coast of Sweden to El Ferrol in north-west Spain, arriving on 2 August 1962, where she underwent restoration work, presumably as part of the deal for the change of ownership. Two weeks later the former Bon Jour and latterly Magda Maria had once again been renamed, she was now called Mi Amigo.

The Magda Maria anchored outside UK territorial waters some 5 miles south of Clacton pier on 24 September. It has been to the Hook of Holland for a few days but is understood to be returning soon. So far as we are aware no broadcasts have yet been made from the vessel. If it starts, as it is Panamanian registered and there is as yet no UK legislation of the type discussed at the Council of Europe, there is little we can do to stop it.

The National Archives, HO 255 602

But the programmes of Radio Atlanta failed to materialise; something had gone wrong with the deal. An incident off the coast of Denmark was blamed for the delay. DCR, a radio station aboard a ship in the Baltic called Lucky Star and associated with Radio Mercur, had returned to the air just days after the introduction of the anti-pirate radio law. Three days of broadcasts followed before Danish police boarded the ship and towed the vessel to the port. Some of Project Atlanta’s backers became nervous after this move by the Danish authorities and, fearing they might lose their investment, withdrew their funds, leaving Crawford with insufficient capital to complete the deal. But were Crawford’s cautious investors the real reason for the deal failing, or was he perhaps holding out for a better deal, a deal where Project Atlanta was exposed to far less risk?

Nobody was really sure what the reaction of the British authorities would be to a radio ship broadcasting off the coast and, should they have raided the ship once Radio Atlanta went on the air, the group would have lost everything. But, if the ship was still owned by the Americans it might have caused the British Government to delay any action for fear of the situation involving other nationalities and becoming far more complicated, thus acting as insurance for Crawford.

I tried to persuade them that they could remain owners and I could operate off England, but they didn’t like that idea, and while I was busy with the formula under which we could successfully operate in England, they got scared, as money men often do, and they took it all back to Texas.

Allan Crawford

Just how close Radio Atlanta came to becoming Britain’s first offshore commercial radio station broadcasting from the UK coast in September 1962 will probably never be known, but the radio ship was in position and she was ready to go. Instead the Mi Amigo spent the next four months at various anchorages and ports around the North Sea; for a while she was moored close to the Radio Veronica ship off Holland. She then entered the Belgian port of Ostend and later reports placed her in the port of Flushing.

Various rumours about the ship being used for television broadcasts and even being sold to the Cuban authorities circulated. Belgian newspapers reported the ‘mysterious radio ship’ was to anchor off the French coast with daily commercial radio broadcasts starting on 18 December 1962. According to ‘a reliable source’, a British millionaire had paid 5 million Belgian Francs for her. But all of these plans and rumours came to nothing, the owners decided that a deal was unlikely and ordered the Mi Amigo to sail to Galveston.

My Texan friend, who had seven radio stations, was considered one of the bright executives of America, rang me and said, ‘we’ve got it from the horse’s mouth that you’ll never be able to get away with opening a ship there’ and he withdrew his ship to Texas. I was broken-hearted; I depended on getting that damned ship, the Mi Amigo, for us, because it was already equipped for radio.

Allan Crawford

The transmitting mast was partly removed and, on 26 January 1963, the Mi Amigo sailed from Belgium, with reports of a stop on the way at Brest in western France to repair the steering gear, before crossing the Atlantic and eventually mooring at Pier 37 in Galveston, Texas on 14 March 1963.

The plan now was to remove the radio equipment and convert the Mi Amigo into a luxury yacht or recreational fishing vessel. Her crew were all paid off on arrival and she spent the long summer months in Galveston. She became a feature of the harbour with little activity around her; newspaper reports called her ‘The Lady of Intrigue’ and speculated that she had broadcast as the Voice of America, fighting for the freedom of the west against the communists.

Later reports revealed that radio equipment on board had been bought by local radio station KILT, another of Gordon McLendon’s stations; although it was likely that the radio equipment on board Mi Amigo was dismantled sometime after arrival in the Texas port.

We replaced the older cartridge machines and all studio mics with the relatively new Collins machines and Telefunken microphones that were removed from the MV Mi Amigo, which was home to McLendon’s pirate radio ship operation off the coast of Norway. When Radio Nord was disassembled at Pier 37 in Galveston, KILT was the recipient of a good bit of studio gear.

houstonradiohistory.blogspot.co.uk

Bill Weaver, KILT’s programme controller and local representative of the Rosebud Shipping Company of Panama, the registered owners of the ship, told local journalists that the ship was for sale. Newspaper reports described her Panamanian flag as tattered and her green-painted hull in need of care. The Mi Amigo was to stay alongside the pier in Galveston for eight months.

___________

* The Pilkington Committee on the future of broadcasting was set up in 1960 and its findings were published on 27 June 1962. It concluded there was no need or desire for commercial radio in Britain.

3

THE ‘WHY NOT’ BUSINESS

Radio Caroline was the first of the British offshore radio stations. It was started by Irishman Ronan O’Rahilly and without him there would have been no Radio Caroline, but what led O’Rahilly to start this radio revolution in the UK?

Ronan O’Rahilly had legitimate Irish Republican credentials; his family were part of the recent history of the island of Ireland. His grandfather was Michael Joseph O’Rahilly, shot by British soldiers while taking part in the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin. Known in legend as The O’Rahilly, his life was celebrated in a poem by Yeats and a street in Dublin close to where he fell bears the family name.

Married to an American, Ronan’s father, Aodhogen, also had an interest in the politics of Ireland; he stood for election to the Dail, the Irish parliament, in 1932, but failed to win a seat. As an educated engineer, he became a successful businessman with involvement in the peat and building industry and forestry. In the mid-1950s he bought the port of Greenore in County Louth from British Railways for £15,000. Earlier in the century it had been an important rail and ferry port for onward travel to England, but with closure of the railway in 1951 the ferry service to England came to an end and the whole site had lain redundant. Ronan O’Rahilly came from this wealthy background.

Born in 1940, O’Rahilly took pride in being a rebel; he claimed that he was expelled seven times from school. He moved to London at the start of the 1960s and quickly got to know the people who frequented the coffee bars of Chelsea. It was a place to be hip and cool and with his charm and good looks, he soon became one of the coolest in the Chelsea set. Whether he benefitted from family wealth, or not, money didn’t seem to be a problem.

He became involved in a drama school, Studio 61, in the Fulham Road, practising method acting, a technique created by Russian Constantine Stanislavski. The actor ‘becomes the part’ and takes on the persona of the person being portrayed. Also attending these classes was Giorgio Gomelski, who would become involved with the Rolling Stones in the band’s early days and go on to become an influential music producer. Another student at Studio 61 was former RAF man Cyril Nicholas Henty-Dodd, soon to be known by millions as Simon Dee. Whether Ronan was qualified to teach isn’t clear, but he then moved to London’s club land in Soho, running the Scene Club in Ham Yard off Great Windmill Street. This was one of a number of hip clubs in London, a place where rhythm and blues ruled. Artists playing here included Geno Washington, Chris Farlowe and Zoot Money; most of them were on the books of impresario, promoter and club owner Rik Gunnell, but their management was the responsibility of others. The Rolling Stones also appeared at the Scene, appearing on stage on four occasions in June and July 1963.

I believe Ronan was the owner of the Scene, at least that’s what we all believed. The Scene club was dark, cramped and narrow, with a small bar, what passed as a dance floor and a stage too small for anything other than a DJ who had to make room for live bands and their equipment; consequently, it was very loud. There were some tables at the back, but I’m not sure anyone sat at them. It always seemed crowded, even when, quite often, it seemed there were only twenty people in there. The walls were invariably running with condensation, I don’t remember seeing an emergency exit anywhere, I didn’t go near the toilets due to pushers plying their trade, so maybe there was one there. One of the reasons that the Scene was not one of my favourite venues was because you almost always got hassled by someone wanting to sell you drugs, usually pep pills like purple hearts or bomber or dubes and I was not into that even though it was as common then as smoking is now amongst my contemporaries. The place rocked though, they got records straight from the States so you heard stuff that never would have got played on the radio.

Steve Cook, roadie with Zoot Money

The musicians performed the songs they’d heard on the imported American records that were played during the band breaks at the Scene: blues, jazz, soul and ska; black music, so different to the hits performed by established British artists, accompanied by strings and orchestras and played on the radio at the time.

Ronan O’Rahilly was responsible for the day-to-day management of a number of artists at this time; he was certainly working with harmonica player Cyril Davis and legendary blues musician Alexis Korner. Another of Ronan’s protégés was blues singer Ronnie Jones, an American serviceman based in Britain.

Well, he started out trying to tame Alexis Korner. He invested in suits and stuff which the guys took and laughed about. I was still in the American Air Force being discharged and it was then that Ronan asked me to return. Alexis had asked me too, and I was undecided. I chose Ronan; I figured it’d be the shortest step to success. How wrong was I? Apart from my first two recordings he wasn’t around that much. I do know he never gave me a dime for the singles that were produced on the various Decca and CBS labels, just a weekly salary and he paid for my flat in the first three months.

Ronnie Jones, musician

Ronan was instrumental in bringing the Alan Price Combo to London from Newcastle. Keyboard player Price, lead singer Eric Burdon, John Steele, Hilton Valentine and Chas Chandler became The Animals during this time.

We were resident at The Club A’GoGo in Newcastle and Ronan came up to see us, and he was moving with the smart set in London. We were taken down there and had a meeting at the Carlton Towers, a swish hotel. Ronan knew how things were done, he was very hip, he really fancied himself, but he had a lot of ‘get up and go’ and verve. He helped to launch The Animals, but he and the manager had a split up and he always felt slightly resentful that he didn’t get a slice of The Animals – but he was there at the birth.

Alan Price, musician

Keyboard player and vocalist Georgie Fame had a residency at the Flamingo Club and he also performed at the Scene and it was Ronan’s attempts to promote a recording of Georgie Fame that, he claims, led him to start a radio station.

I can remember well going round with an acetate of Georgie after I’d discovered that the BBC wouldn’t play it at all because it wasn’t on EMI or Decca, and I suddenly realised that the whole thing was locked up. I remember sitting with the head of Luxembourg and he had two of his colleagues in the office with him and I said, ‘here’s the acetate. How many plays can I get, will you play this?’

I knew I needed airplay in order to get the thing to function and when I’d finished rabbiting about how many plays I’d get, there was spontaneous laughter. The idea that somebody could walk in and believe they could get a recording played … and then he pointed out all these boards on the wall and there was EMI Show, Decca Show, EMI Show, Decca Show all listed and I said, ‘do you mean to say that every record I’d ever heard on Luxembourg was paid for?’, and he said,’ you’re absolutely right. We’re booked up for five years’. I said, ‘well, it looks like I’ll have to start a radio station of my own’, and with that they became very unhappy and they said, ‘you can’t do that’ … I said, ‘well why not? You’ve done it.’

Ronan O’Rahilly, ‘The Radio Caroline Story’, EAP Studio & radiofab.com

Ronan has said that he was aware of other radio stations broadcasting from ships, in particular the Voice of America and the Dutch Radio Veronica, but now there were two would-be radio operators chasing the same dream. The question that many have puzzled over is who came up with the idea first? Interestingly, although Project Atlanta was formed in 1962, it wasn’t until February 1964 that Planet Productions, the company behind Caroline, was registered. Allan Crawford has always maintained that he had the idea long before O’Rahilly.

One of the people I met, who came into my office was Ronan O’Rahilly, it must have been late 1962, and he’s a very personable bloke, a very likeable bloke, charming manners and so on, and naturally one likes him and, like an idiot, I trusted him, especially when he said, ‘my father’s a rich man, living in a beautiful house in Dublin and I’ll take you to meet him. If you give me a set of the papers I’ll take them to him and interest him in being one of your investors’.

So I went over to Ireland, he was absolutely right, beautiful house on the outskirts of Dublin. The father himself drove us to the border abutting Northern Ireland and there was this port. It hadn’t been used for a long time and it had fallen into neglect, but there was a jetty for ships to tie up alongside and he said ‘you can come here, it’ll be kept quiet. You can equip your ship, and I’ll see to it that you won’t have any trouble.’

Allan Crawford

Part of the plot, which I didn’t know when I first met him and met his father was that the father would get possession to the key to the whole thing which was the QC’s opinion as to why it could be legal. Innocently, I gave him a copy (while looking for financial backers) and he must have given it to Ronan who then was able to run around showing this to his backers.

Allan Crawford, Arena: A Pirates Tale, BBC TV, 1991

We’ve both given each other a great deal of advice. It could be that I took less of his, than he of mine.

Allan Crawford, ITV World in Action: The Pirates, May 1964

Ronan O’Rahilly met up with Allan and said he owned a harbour in Ireland and he could do the whole thing without any problems at all, this seemed like the answer to our prayer. Although he wasn’t prepared to put up any money, the fact that he could offer this harbour with the facilities that we needed seemed to be sufficient reason for including him in the deal. Therefore, in order to convince Ronan of the viability of our totally legal operation, Allan had to give him the full details of the entire set-up with details of the banking facilities, the flags of convenience and the amount of money that had already been promised. Ronan was therefore fully conversant of the modus operandi of the entire set-up. He said that he was totally in sympathy with the project, and that he couldn’t agree more with the way it had been set up. He was absolutely, one hundred per cent committed and the port facilities would be made available in Eire.

Kitty Black

But although Project Atlanta had come close to securing the purchase of the Mi Amigo in 1962, the man operating Radio Nord remembered others showing an interest in the ship.

In the last days of Radio Nord I was visited by a shipowner’s son who was named Ronan O’Rahilly, together with a Swede. They wanted to buy the boat, but their appearance and impression on me was that it was empty talk, so I didn’t bother to take their offer seriously.

Jack Kotshack, in an interview with Ingemar Lindqvist