Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

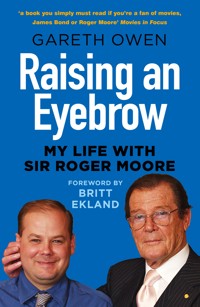

'a book you simply must read if you're a fan of movies, James Bond or Roger Moore' - Movies in Focus 'Owen writes with wit, affection and poignancy . . . Highly recommended' - From Sweden with Love 'a breezy, enjoyable read that takes few sittings to get through . . . The affection and energy with which Raising an Eyebrow has been written is intoxicating' - Entertainment Focus Having taken on the role of Roger Moore's executive assistant in 2002, Gareth Owen became the righthand man to an icon, as well as his co-author, onstage co-star and confidant. Gareth was faithfully at Roger's side for fifteen years until his passing in 2017. In Raising an Eyebrow, Gareth Owen recounts his times with Roger Moore and gives a unique and rare insight into life with one of the world's most beloved actors. For all his celebrity, Roger Moore was quite reserved; in interviews he rarely spoke about himself, much preferring to tell fun tales about others. But his trusted sidekick was with him throughout his worldwide travels, his UK stage shows, his writing process and his book tours, and as he received his Knighthood. There were genuinely hilarious, heartfelt and extraordinary moments to be captured and Gareth Owen was there to share them all.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 329

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2020

This paperback edition first published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Gareth Owen, 2020, 2021

The right of Gareth Owen to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9449 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword by Britt Ekland

Prologue

Chapter 1

Impressionistic Days

Chapter 2

Pinewood Bo(U)Nd

Chapter 3

Would You Relieve Me?

Chapter 4

Move Into Writing (and Roger’s Office)

Chapter 5

Bondstars

Chapter 6

The Collapse

Chapter 7

Knighthood

Chapter 8

Kipling

Chapter 9

More Bonding & Kipling

Chapter 10

Books & Boats

Chapter 11

Publication

Chapter 12

The Book Tour

Chapter 13

Pork Pies & the Post Office

Chapter 14

Saintly Endeavours

Chapter 15

Hairy-Arsed Bulgarian Electricians

Chapter 16

Bond On Bond

Chapter 17

One Lucky Bastard

Chapter 18

Scotch Egg Gate

Chapter 19

Flossie

Chapter 20

The Final Show

Chapter 21

The Last Trip

Chapter 22

Farewell Dear Friend

Postscript

Thanks

Foreword By Britt Ekland

Having known Roger for many years as a friend and as a co-star in The Man with the Golden Gun, I can honestly say he was one of the most charming men I’ve ever met. He was also one of the busiest. He never stopped working: TV, film, writing books, touring his show and, of course, his work with UNICEF.

But when you are working that hard, there’s always someone in the wings making sure it’s all running smoothly. In Roger’s case it was his long-time private secretary, Gareth Owen.

Gareth knew Roger better than anyone, even some of his wives, and he could usually second-guess and keep one step ahead of him, which was invaluable.

But beyond that, they were the best of friends – that was so evident to anyone who saw them together. They were so very loyal to each other, and even shared the same naughty sense of humour …

I’m delighted Gareth has written about their years together. This book is insightful, fun, poignant and, just like their working relationship, so unique. Roger was indeed the nicest man ever!

Prologue

The last time I saw Roger in person was early March 2016, a couple of months before he died.

I was leaving his chalet in Crans-Montana, Switzerland, after spending a week with him and his wife, Kristina, following his discharge from hospital in Lausanne to ‘build up his strength’ in readiness for his next round of cancer treatment. Whilst a tiny part of me knew it might be the last time I saw him, I never really thought it possible that my hero would ever die; he’d always said, when people asked him how he would like to be remembered, ‘as the oldest person in the world’ – and I believed him.

I prepared some of the leftover cottage pie I’d made him earlier in the week and left it in the microwave for Kristina to heat up along with some vegetables for his lunch, an hour or so later. He thanked me for coming and wished me a safe journey home, and Kristina hugged me tightly but silently – her silence spoke volumes. We were both still in shock that this was happening.

I got into the taxi that had pulled up outside – much to Roger’s chagrin as he had wanted to drive me to the funicular station, despite being barely able to walk around his house – and waved goodbye. The five-minute drive to the station was so very full of emotion with various thoughts and worries running around my head. But it had been a good week – we’d worked on his book, we’d watched a few movies, I’d made him his favourite meals and we’d even ventured out to lunch once – so I convinced myself to be full of hope and optimism. The thirty-minute funicular trip, followed by a two-hour rail journey to Geneva airport and a flight back to Heathrow, was always a tiring adventure, more so this time as I couldn’t stop thinking of him.

Roger and I spoke regularly in the days and weeks afterwards, and up until 12 April we saw each other on Skype video calls. That was the day of our last Skype call and after that the phone calls became more sporadic as his illness took a firmer grip on his mortality. The last time we actually spoke was a few days before he died, when his daughter Deborah was with him in hospital, in Sion, and she’d called me to say he wanted a word. I know he’d been drifting in and out of consciousness and when he greeted me with, ‘Hello boyo, how are you?’ in a very weak voice, I tried to think of something to reply; I couldn’t say, ‘Oh I’m fine, how are you?’ because I knew exactly how he was, so instead said, ‘It’s so good to hear your voice.’ Just then he gave out a moan of pain, and Deborah took the phone back to tell me he was trying to get comfortable in bed and she was going to adjust his pillows.

By the following week, he’d gone.

I’d never known a world without Roger Moore. Life suddenly seemed very strange, and eerily quiet.

CHAPTER 1

IMPRESSIONISTIC DAYS

Roger Moore is all around me – there are snaps and some posters on my office walls – and every day there is something to remind me of him, be it a conversation, a place, an experience, a film or TV show on the box, or just a happy thought. In fact, all my thoughts of Roger are happy – well, all but the last weeks of his life.

I miss him hugely because he was a huge part of my life, first as an actor and cinematic hero, then as my boss, my co-author, co-host and above all, my best friend, and I know I was one of his most trusted friends too. The relationship between any personal assistant and their boss is a close one, professionally speaking, and with Roger – although he was largely based overseas and I at his Pinewood office which he’d had since 1970 – we spoke regularly and spent time with one another in the office, at his home and in all corners of the world. A PA is a bit like a family member in that you are so much a part of their private life, their routines, their diary, their family, their woes and worries, their frustrations. Sometimes you’re closer than family, and certainly always trusted as a member of the family.

I’m often asked, ‘How did I come to work with him?’ I quite often reply, ‘There was a notice in the post office window saying, “Megastar needs new PA”.’

‘Really?’ they ask, with great interest.

‘No! Not quite,’ I reply and evade giving a proper answer.

I suppose part of a PA’s role is to be discreet, not to give anything away, and to be honest I’m a very private sort of person anyway; and I liken such questioning to a total stranger approaching you and saying, ‘I hear you work at the bank, how did you get that gig?’ or ‘I hear you’re a plumber, who gave you that job?’ – that probably rarely happens I realise, but mention you work for someone famous and all of a sudden everyone’s very interested. Curiosity? A hint of the untouchable?

But how did I get the job? Well, it’s a long story involving a bit of a journey, which taught me a lot of skills, made me a lot of contacts and helped me develop as the person I am – all invaluable for ending up as a PA to an international megastar (tongue firmly placed in cheek).

I was born in 1973, the same year Roger Moore debuted as James Bond 007 in Live and Let Die. There must have been some serendipity, as he was to become my favourite film star and the James Bond series became something of an obsession with me – and he was of course was my favourite 007.

My parents were great cinema-goers, or as they would say, they liked ‘going to the pictures’. I have several hazy memories of the Odeon in Chester, and my pushchair being left in the manager’s office downstairs as I was carried up to the main screen upstairs, as there wasn’t a lift. That was back in the days of having to queue to see a film, and the queues quite often stretched around the block into Northgate Street and the manager would walk down, counting people, and when he reached a point in the queue he’d apologise and say, ‘the house is full beyond here’. I recall wanting to see The Rescuers (1977) and being turned away, only for my mum to persuade the manager to let her sit on one of the small fold-down usher seats at the back of the auditorium with me on her lap.

It was there at the Odeon, aged 4, that I saw The Spy Who Loved Me (1977). There was something magical about it, not least the white underwater Lotus Esprit car – a toy Corgi model of which I bashed and bruised with gusto during my own pretend adventures at home – and the villainous steel-toothed Jaws left a lasting impression. Though I loved going to the cinema – and had done so since being a babe in arms, my mother professes – there was something different about this trip, and the seeds were very much sown.

I had to wait until Christmas 1978 for my next taste of 007, four or five years before VHS and rental video shops appeared in the UK, when a Bond film premiered on television. It was the first time ITV had screened one of the series at Christmas, thus beginning a long tradition; however, I was shocked and horrified to discover it wasn’t the real James Bond. It was someone else pretending to be 007! The film was Diamonds Are Forever (1971) and its star was a chap named Sean Connery. Despite protestations from within the house that he was the original James Bond, I couldn’t nor wouldn’t have it – I wanted Roger Moore.

The summer of 1979 came around, as did Moonraker, and I became more aware of the series and Roger’s predecessors in the roles, though couldn’t get my head around why George Lazenby made one and then Sean Connery came back – but then again, I’d challenge any 6-year-old to grasp the contractual ins and outs of life at United Artists (the films’ distributor and financier). Though criticised for being more fantastical than believable, for a youngster who’d just lapped up Star Wars and Close Encounters, it was bang on the money of the space fascination adventures we were all enjoying.

I totally ‘got’ that Roger Moore was an actor and not just James Bond, and became aware of other films he’d made – though I hadn’t been allowed to see the more violent ones such as The Wild Geese (1978) – and there was also something about a TV series or two he’d done, but I had to wait a bit longer for those to come my way as the three TV channels we had weren’t running them as, I was told, Roger Moore didn’t want them on TV again. Actually, it was more to do with a royalties negotiation but as I say, you can’t expect a 6-year-old to know much about all that. The more I saw of Moore on screen, the more I liked him; I liked him in interviews too, as he had a childish sense of fun and never took things too seriously. He soon became my favourite movie star and I’d cut pieces out of the newspaper and film brochures from the cinema lobby and yearned to see yet another new Bond film. Fortunately they were produced fairly regularly back then, coming out every two years.

I remember once watching the (then) popular Fix It programme on a Saturday early evening, where people wrote in to the show asking for the host to ‘fix it for me to …’ This particular episode featured Desmond Llewelyn who played Q in the Bond movies, and some young chap who wanted to meet him and get to look at the gadgets he made for 007. Desmond – a fellow Welshman – came across as being absolutely lovely, kind, generous and witty. He carried a battered old attaché case around with him that was featured in From Russia With Love (1963) where Q armed that other fellow with a few gadgets. None of them really worked; they were film props, but it was fascinating to hear Desmond talk about working on the films and laughing off his own technical ‘uselessness’. So I thought I’d try my luck and write in to the programme, asking them to fix it for me to meet my hero, Roger Moore. I said it was my lifelong ambition – all eight or ten years of it – and took my carefully written and spelling-corrected letter to the post office, bought a first-class stamp and popped it in the post box.

I checked the mail delivery at home every day for weeks (months!) to see if any reply had come for me – we didn’t have a telephone at home so it was the only contact I anticipated – and sure enough … nothing. Not a word, not an acknowledgement, nothing. ‘Perhaps Roger is busy,’ I told myself. I never gave up hope of one day meeting him.

I collected the odd bit of Bond memorabilia whenever I saw it – toy cars, a music LP, books, etc. – and eagerly awaited news of any new film, although the only way of garnering any titbits was through the odd story in a newspaper. Google hadn’t been heard of, nor had the internet come to that. I’d drool over any behind-the-scenes photo that appeared in the News of the World ‘from the set of the latest Bond film’ – it was like manna from heaven.

I vividly remember going to see Octopussy (1983) when I was 10. We’d planned a summer camping trip to Prestatyn, near Rhyl in North Wales, with the four-man tent I’d had for Christmas the previous year. Life under canvas was to be a huge and new adventure, and once experienced, rarely sought after again. But a holiday without electricity or a television, even for a few days, proved a challenge when it came to the evenings; after a day out doing whatever we did, we returned to base for a camp meal and then wondered what to do. We could have talked, I suppose? No! We opted to ‘go to the pictures’ and it just so happened Rhyl had two cinemas at that time: the three-screen Apollo (a former Odeon) and the Plaza, a slightly less loved two-screen cinema that was soon to be closed and converted to an indoor market. The Apollo had the latest James Bond film, whilst the Plaza was screening Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), so we got to see them both. Octopussy pitted the Russians against the good guys, offered an exciting chase on tuk-tuks, villains on elephants and even a hot air balloon coming to the rescue, plus the usual mix of gadgets, girls and Roger’s own unique take on the character. There had been newspaper headlines about the ‘Battle of the Bonds’ as Sean Connery had been lured back to play Bond in the unofficial Never Say Never Again (1983), but the latter film had been pushed back to a Christmas release to avoid a head-to-head box office battle with the official series – though Roger of course played in the most successful of the two movies. Take that, Sean Connery!

I recall talk of Roger retiring after Octopussy as the critics were saying he was getting too long in the tooth to play 007 again. In fact, Roger later told me he had wanted to bow out and felt it was the perfect film to end on, as he’d really enjoyed making it and it had performed admirably at the box office. Financial temptation can be a wicked thing, though, and producer Cubby Broccoli teased him to the point of not being able to refuse returning in A View to a Kill (1985) – which I went to see at my beloved Chester Odeon, screen one, upstairs.

I was greatly saddened to hear Roger announce he was stepping down in 1986, after seven outings for Eon Productions, yet unlike his predecessors (and successors) he remained a wonderful ambassador for the franchise, always talking positively, embracing interviews and being fully supportive of the other actors who picked up the Walther PPK. But that was Roger all over; why be negative when you can be positive and be part of something popular? The desire to be loved was always his weakness.

Soon afterwards Roger hosted an ITV documentary celebrating 25 Years of James Bond from what I thought was his own Swiss chalet – it was actually a location they’d hired. Roger never allowed film crews or journalists into his home (though Hello magazine did pay hugely for the privilege once or twice!) as he reasoned, for one thing, it was his personal, private space and he didn’t want anyone commenting on or judging his taste, or worse, gossiping about it in print or on TV; and secondly, he reasoned that if he had based his company at home then he could have claimed a tax relief and that would have then been fair game to host interviews as it was a place of work, but actors never received such a tax break, so why should he allow his home to become a place of work in that sense? So he’d always request interviews be at a hotel or another venue, such as the local golf club – not that he played, he just dined there!

Timothy Dalton succeeded him as Bond, though Roger tactfully dodged any questions about what he thought of Dalton in the part by simply smiling and saying, ‘I’ve never seen his films I’m afraid.’

It was around this time that I became aware I wasn’t alone as a Bond fan. Up until then it had seemed as though, as popular as the films were, they hadn’t the visible fan base that Star Wars, Back to the Future, Indiana Jones, etc. had, where their memorabilia was everywhere and it was cool to say they were your favourite movies. Bond seemed to be a bit more underground, but that changed when I discovered the James Bond Fan Club.

In 1990 it was announced the fan club would be holding a convention – its first in a few years – at Pinewood Studios, the home of the James Bond movies. Wow. What’s more, via an advert in the 007 Magazine I’d learned about a 007 Collectors’ Club run by the lovely Dave Worrall, and through that club my own little Bond collection started swelling with purchases of posters, books, toys, merchandise – one item being a ‘50 Years of Pinewood Studios’ publication from 1986, with some terrific features including a chapter on 007, and furthermore it mentioned that Roger Moore still had an office at the studio. The chance of visiting the Bond Mecca that is Pinewood, along with maybe walking past his office, was a temptation too great to resist, so off I went to the building society to cash in some savings and send a cheque for £100 to the fan club for a one-day ticket (the two-day ticket plus extra accommodation was a little out of my savings’ grasp I’m afraid). Happily I was one of the successful 200 attendees, and on 29 September 1990 walked through the gates of Pinewood – home of Bond, Carry On, Norman Wisdom, Superman and so many other great films – for the very first time.

It was a day that changed my life.

CHAPTER 2

Pinewood Bo(U)Nd

Following the convention’s morning film screening of From Russia with Love (1963), we fans were escorted to the Pinewood canteen for lunch. There were a few journalists in attendance and one ambled over to me and asked if he could have a word, introducing himself as being from one of the local area newspapers. I dare say some journalists were there to do a fun piece on 200 geeky fans turning up in anoraks and clutching plastic carrier bags full of tat, but this chap seemed genuinely enthusiastic about being there himself. He asked the inevitable, ‘Who is your favourite James Bond actor?’

‘Roger Moore,’ I said proudly.

I should point out that by this point Timothy Dalton had made two films and was widely praised as being ‘the best ever James Bond’, but as I’ve gone through life I’ve generally found the present incumbent is usually hailed as the best, though Sean Connery – being the first and original – still holds a huge affection and respect amongst fans.

‘And why Roger Moore?’ my interviewer asked with genuine interest; perhaps he’d never met a live RM fan before?

‘Because I identify with his sense of humour,’ was my considered reply.

‘Good answer!’ he said, before going off in search of the George Lazenby fan.

It was then that Dave Worrall, from the Collectors’ Club, stepped forward as our tour host – he was going to take us on a walk around the studio.

Nondescript corridors became places of marvel as we looked at the film posters adorning the walls, and then when we all turned a corner the huge ‘007 Stage’ stood in front of us, dominating the landscape, and what’s more we had permission to go on there. In walking around Pinewood it became apparent this was a once much-loved studio now down on its luck with peeling paintwork, crumbling walls, workshops propped and patched up; it was exciting yet sad to see. Adjacent to the 007 Stage was a gated set; security men were there to open up and allow us to venture on – it was the Gotham City set from Tim Burton’s Batman (1989) which had been left standing for the proposed sequel, which alas never materialised – at Pinewood. We walked around, ran up the steps of City Hall and snapped away with cameras. As though that wasn’t excitement enough, we were then escorted to B-Stage where the large soundproof door was raised to reveal an Aladdin’s cave of Bond treasures – Aston Martin and Lotus cars, props, costumes, models and a number of actors including Desmond Llewelyn, seated behind tables in readiness to sign autographs (for free!). When I eventually worked my way around to Desmond, he asked my name and then asked if I was Welsh.

‘Yes, from Wrexham,’ I replied.

That seemed to delight him as he was once stationed in the town with the Royal Welsh Guards and he chatted away to me for ages – well, probably a minute or two – but I was so touched and so delighted.

I left Pinewood that night with a spring in my step. Not only had I met 200 fellow Bond fans, I’d spent the most magical day at the most famous film studio in the world. Aged 17 and studying A levels, I hadn’t really decided what I wanted to do for a career and had toyed with ‘safe’ jobs such as banking or teaching, but that day at Pinewood changed all that. I was determined I wanted to work in the film industry, and not just anywhere – I wanted to work at Pinewood, to have my own office and parking space there and maybe, one day, just happen to bump into Roger Moore.

As luck would have it, I was able to return to Pinewood in spring 1991 when Dave Worrall launched his book The Most Famous Car in the World there, which was all about the Aston Martin DB5 as made famous by Sean Connery driving it in Goldfinger (1964) and Thunderball (1965). Dave had been trying to get the book published for some time, but the traditional, big publishers all told him it was too niche and too specialised to stand any chance of being commercial. Long before self-publishing was economical, Dave decided to go out on a limb and publish the book himself and figured if he had several hundred subscribers to his magazine, chances were he could pre-sell a quantity, which would in turn help offset the upfront costs. That’s exactly what he did and turned out a terrifically well-researched, -written and -designed tome – that sells for hundreds of pounds nowadays. Anyhow, his launch party was at Pinewood and featured a number of Bond alumni and gave me a chance to reacquaint myself with the studio once more.

Bond conventions at Pinewood actually became annual events from 1992 onwards for four or five years, always lavishly put together by Graham Rye, with various guests from the series ranging from George Lazenby to Lois Maxwell (Miss Moneypenny), Christopher Lee (Scaramanga), Desmond Llewelyn (Q), Maurice Binder (titles designer), Peter Lamont (production designer), Guy Hamilton (director) and others. Though he was always invited, Roger Moore never attended – I was thwarted again!

I’d meanwhile drifted into university in 1991 – I say drifted because I had no firm career plan, other than aspirations, and if nothing else it was one way of buying me time to decide what I might go on to do and how I might achieve it. I arrived at Bangor University, it being the most appealing of the ones I visited because it was in a relatively small city, on the seaside in beautiful North Wales and it had a decent reputation. My first year accommodation was in halls and I made some good friends both there and on my Electronic Engineering course, which, after the first foundation year, I switched to Applied Physics and Electronics; the main difference being there was more physics than there was computer engineering, as whilst I didn’t (and don’t) mind using computers I have no desire to get to know how to design and program them.

I had a bit of a bee in my bonnet at the time about the film industry, which really was in the doldrums, and I remember reading in the early 1990s that there were on average fifteen British films produced a year; it was no wonder Pinewood looked a bit tired and unloved last time I visited. It was as though I had an uncanny knack of opening a newspaper or magazine, or switching on the TV or radio, where there’d be someone bemoaning the state of British film, the lack of support the industry received – in comparison to the French and Irish industries – and the mass exodus of our talent overseas. Richard Attenborough and David Puttnam were usually brought in to comment and I think there was a feeling of, ‘Oh no, not them again.’ Yes, they were successful Oscar winners who cared passionately for the business, but I felt they were becoming overused – public empathy is a strange thing, and when rich, successful film-makers bemoan they can’t get films made it didn’t really rouse people into action.

Whilst realising a 19-year-old physics student couldn’t do much to help, I thought I should at least be more aware of the problems and obstacles facing British film-makers and what better way than to contact some of them? I first wrote to my MP (Labour) to see what government support there was (or wasn’t?) particularly after reading of the huge importance the French government placed on their industry: a flag-carrying, culturally crucial part of French life. I was of course told of the bold plans with which Labour hoped to develop to support the industry, should they get into power at the next election, and the lack of the current Tory administration’s support for it – free enterprise should, the Tory party believed, sink or swim on its own merits. It wasn’t a government’s role to prop it up.

I wrote to the Tory administration: there wasn’t a film minister or Department of Culture back then; film fell under the remit of the minister of trade, further underlining the government’s lack of interest in fostering a native film business. I received a rather condescending letter back telling me the government fully supported British film, and as such were ‘giving’ £14 million annually to the British Film Institute and furthermore investing £5 million over three years as ‘pump priming finance’ in the Eurimages initiative of the EU. Yet back then the BFI was chiefly concerned with preserving film, supporting education, publishing and offering a modest production fund to a few select film-makers. It wasn’t anything like the funding body of today and didn’t play any role in government policy.

So why was the business languishing? Was there a lack of appetite for home-grown product? Was there a lack of cinema screens? Was there a lack of decent distribution? I think the answer to those and other questions was ‘yes’. Peter Greenaway was making films, as were Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, but they were not particularly wide appealing, and were viewed as art house, whereas American imported films were cleaning up at the box office. Distributors such as Rank (which also owned Odeon) struck deals with American producers to supply their company with products in exchange for minimal investments (and risk) – and there were so many American films to choose from.

Feeling a little frustrated I sought views from veteran film-makers, actors, writers, distributors, presenters and just about as many other places as I could think of and one thing became clear – the UK was not a welcoming environment for film-makers. There was no logistical support to filming in big cities, there were no tax breaks or incentives. A few years earlier Lewis Gilbert took his production of Educating Rita to Dublin; he was about to be followed by Mel Gibson with Braveheart when, after setting up in Scotland, Gibson found little support and help yet the Irish offered him their army to serve as extras and a tax incentive. The last Bond film, Licence to Kill, had decamped from its traditional home at Pinewood to Mexico for better tax deals too.

It struck me that – whilst I didn’t understand all the tax implications – there was a benefit to having a big production move in, not least in employment and local spend, but also in attracting others to follow. Britain was at risk of losing out. Continuing my research into the problems and potential solutions, I knew I’d only make headway if I could garner some serious names in support. To my surprise, and delight, they came thick and fast: Anthony Hopkins, Jeremy Irons, Bob Hoskins, John Cleese, Emma Thompson, Julie Walters, Bryan Forbes, Michael Relph, Roy Boulting, Guy Hamilton … and many others. It certainly helped me gain some headlines in trade magazines and this 19-year-old physics student suddenly became someone making a noise from the public’s point of view. Film Review magazine ran a feature on me and asked ‘what next?’ Thinking on my feet I announced, ‘a showcase of British film – a British film weekend to really hammer home what we have done and what we can do again.’

But where? When?

I went out on a limb and contacted the manager of Theatr Clwyd – a huge theatre, gallery and cinema complex in Mold, North Wales – and in my letter explained that I wanted to stage a weekend event. I didn’t get a reply, so after about ten days I wrote again and said I’d follow up in a phone call, which is exactly what I did – and I think I caught him on the hop as he invited me over for a meeting, although I could sense the reluctance in his voice. Elis Jones turned out to be a very jolly, friendly guy who was actually titled ‘Programme Manager’ and in charge of looking after the venue’s calendar. We had a chat where I said I’d like to put together eight films in a single weekend: a Bond, a Carry On, a Hammer Horror, a modern classic, a classic classic … and so on. He liked the idea though questioned the costs involved in programming eight films, as the licences alone would be upwards of £100 per film regardless of whether anyone came to see them. I cavalierly said, ‘leave that to me’ and we agreed provisional dates for the end of February 1993.

I contacted some local companies for potential sponsorship – but none were interested. A sound recordist friend of mine suggested I think outside the box, and approach film companies instead – Kodak being one. To my great delight Kodak came back and said, ‘We’d like to support you, call us.’ I spoke to Managing Director Geoff Cadogan and he said he was thinking of writing a cheque for £500, but needed to know where it would be spent – the bar was not an option. I suggested he sponsored the cost of the print hire – he agreed. I also managed to persuade one of the distributors to let us have their film for free, so I’d like to think Elis Jones was pleased his punt on me wasn’t going to cost him – well, not much.

The next step was to round up physical support and invite celebrity guests. Of course, getting them to travel to North Wales and stay over was another expense, but one Elis said he’d happily help cover as they had a friendly local hotel. Sadly, and as enthusiastic as he’d been to attend, Anthony Hopkins wrote to say his filming schedule on a BBC movie in South Wales would prevent him, but he said he’d be up at Theatr Clwyd soon to discuss a production and invited me to join him and his wife for lunch nearby. He was lovely, and we chatted for an hour or more about everything and he said he could see my passion and enthusiasm and wanted to support that. He offered to pay for lunch, but even though I could barely afford it I insisted I should pay and gritted my teeth as I opened the bill. It was about £60 – but for a student in the early 1990s, that was a couple of weeks’ food money!

For the weekend itself, I was fortunate my (now) friend Desmond Llewelyn said he’d come to represent the Bonds; Jack Douglas, the Carry Ons; and husband and wife Timothy West and Prunella Scales (who starred with Anthony Hopkins in one of the screened films, A Chorus of Disapproval) came too.

It was a really great weekend, with lots of media coverage. I was also asked, ‘So what next?’

‘We’ll do it all again but this time in the south. At Pinewood Studios!’ I exclaimed.

I’d previously interviewed the new managing director of the studio, Steve Jaggs, in my ‘what’s wrong and how might we overcome it’ research – which I was about to publish and submit to the newly formed Department of Culture along with a petition of thousands of names I’d collected at local cinemas during my university holidays, requesting the government take seriously the need for the industry to receive some support. I suggested a tax break similar to the Irish, a small levy on video cassettes (the rapidly growing home media market) and the establishment of a British Film Week in cinemas on an annual basis.

The Department of Culture were aware I was travelling down to present my report and petition, and I think had an office junior on standby to meet and thank me at noon – high noon. But things took an exciting twist when the afternoon prior, having arrived in London, the ITV local news contacted me saying they wanted to be with me on the day – having seen reports on the ITV Wales local news a few days prior – and what’s more, they arranged for Michael Winner to meet me ahead of going into the department. The instructions from Winner were very specific, to meet him at his house at 10.30 a.m. in Kensington and then we could go on to Westminster.

I arrived a few minutes early, and the TV crew a minute or so after me – the reporter was Rachel Friend, ex-Neighbours star, which was quite surreal given I used to watch the lunchtime edition every day during my uni lunch break.

Winner was charming, very kind and hugely complimentary towards me – though told the crew exactly where to set up, how to light it and how long they’d got! From there we crossed London to Trafalgar Square where the department said I was welcome, but could not go inside with a camera. Who cares, I was getting the support of Michael Winner and a TV news crew was in tow.

I was obviously being taken seriously and my merry band of ‘celebrity supporters’ was growing.

Steve Jaggs, at Pinewood, was gracious enough to invite me down for a chat, though I knew he had huge reservations about allowing me to take over the studio for a day of film screenings and celebrations. The last time they’d opened the gates to the public (outside of the Bond conventions) was in 1976 for the studio’s fortieth anniversary – they’d expected a few hundred and a few thousand descended, blocking roads for miles around, and the local council said ‘never again’. Of course, the studio was also a working facility and wouldn’t want any of its customers annoyed by members of the public traipsing around.

I explained to Steve that I envisioned limiting the day to 150-200 attendees, screening three films, holding a lunch, gala dinner and having celebrity guests and displays throughout the day.

He was actually very receptive.

We agreed on a date in fact, 9 April 1994, and it was to be entitled British Film Day at Pinewood.

The day soon came around and with a terrific line-up of film vehicles outside to greet attendees, thanks to my old friend Robin Harbour tracking them down, and actors from Pinewood films including Sylvia Syms, Burt Kwouk, Valerie Leon, Liz Fraser, Jack Douglas, Bryan Forbes, Nannette Newman, Walter Gotell, Eunice Gayson and many others came to join us. Walter came with his wife, Celeste, one of the editors from the Daily Express, and she chatted to me about the day, my aspirations and just how old I was. She couldn’t believe it when I said I was 20 and just about to start my final year exams. Walter sat me down and told me he had a script he was producing as a feature and that we should chat.

Again, I was fortunate to receive some good media coverage, including a couple of pages in Empire magazine which, amongst several other letters, prompted a missive from a businessman named Zygi Kamasa. He wrote that he owned a computer company in Uxbridge and was also a huge film fan, and had toyed with the idea of moving into the film industry but didn’t have any clue as to how to go about it, and whilst he had money behind him he didn’t have any contacts. He seemed to think I might be able to help him.