10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

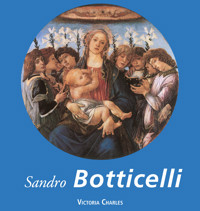

In utter contrast to the obscurity of the medieval period which preceded it, the rapid and unexpected arrival of the Renaissance conquered Europe during the 14th to the 16th centuries. Placing man at its centre, the actors of this illustrious movement radically altered their vision of the world and refocused their aesthetic pursuits towards anatomy, perspective, and the natural sciences. Creator of numerous talents, the Renaissance offered the history of art great names such as Botticelli, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci, whose glorious masterpieces still today hang on the walls of museums the world over.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 123

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Author: Victoria Charles

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-68325-703-5

Victoria Charles

Contents

Introduction

Il Rinascimento

The Renewal of German Painting

The Netherlands, France, England and Spain

Major Artists

List of illustrations

Leonardo da Vinci and Andrea del Verrocchio, The Baptism of Christ, 1470-1475. Oil and tempera on wood panel, 177 x 151 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Introduction

For the entire European economy, the Renaissance was a decisive period. In the 15th century great European families like the Medici from Florence pushed international commerce. Parallel to the increase of fortunes resulting from this trade, art experienced a new time of opulence, especially thanks to the new innovative techniques and the materials which it disposed of. In the 1440s Johannes Gutenberg developed the movable-type printing press, a more efficient and less expensive method than xylography. At the same time, painters set egg based tempera painting aside and orientated towards oils. Filippo Brunelleschi discovered the principles of perspective, a revolutionary method allowing him to overcome the lack of depth found in medieval art by simulating a three-dimensional space. Finally, in 1452, a man was born who is would eternally incarnate the typical Renaissance scholar: humanist, scientist and artist Leonardo da Vinci.

The 16th century marks the heyday of the Renaissance. It begins with the two main catalysts of Protestant Reformation: the Ninety-Five Theses by Martin Luther in 1517, and John Calvin’s intention to reform the church. These movements result in the formation of Protestantism, which focuses on personal belief rather than ecclesiastical doctrine. The invention of the printing press in the previous century had made the Bible accessible to everybody; knowledge of the Scriptures was a main characteristic of the Reformation. At the same time, in the 1530s, the English Reformation, initiated by Henry VIII, leads to a break with Rome, resulting in the separation of the Anglican Church. In these tumultuous times the Catholic Church reacts with extreme measures to regain control over religious belief through the Holy Office of the Inquisition and the Council of Trent (1545-1563) which launches the Counter-Reformation.

In fact, the second half of the Renaissance is essentially marked by these religious revolutions, sealing the end of mannerism. The Northern countries, one by one, adopt Protestantism; the system of artistic patronage is subjected to modifications. The affluence from worldwide trade forms a new class of merchants who order secular works of art for churches as well as for private houses. Still lifes and landscape paintings come into vogue, accompanied by a new market for group portraits resulting from the formation of militias and guilds. Whereas in Northern Europe private individuals remain the main buyers of pieces of art, and therefore are able to choose the subjects, in Italy the church keeps its role as First art patron. Just like it did with Raphael, Botticelli and Michelangelo, the church continues its tradition of supporting artists. In France, artistic patronage centers on the king. The heritage of Francis I, with its fine style, strongly radiates the love of Humanism. It is him who is generally seen as the personification of French Renaissance.

Andrea Mantegna, Madonna of the Stonecutters, c. 1489. Tempera on wood, 32 x 29.6 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Sandro Botticelli (Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi), Madonna of the Book, c. 1483. Tempera on wood panel, 58 x 39.5 cm. Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan.

Il Rinascimento

The Italian Early Renaissance

The earliest traces of the Renaissance are found in Florence. In the 14th century, the town already had 120,000 inhabitants and was the leading power in middle Italy. The most famous artists of this time lived here – at least at times – Giotto (c. 1266-1336), Donatello (1386-1466), Masaccio (1401-1429), Michelangelo (1475-1564), Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455).

Brunelleschi secured a tender in 1420 to reconstruct the Florentine Cathedral, which was to receive a dome as a proud landmark. The foundation of his design was the dome of the Pantheon, originating in the Roman Empire. He deviated from the model by designing an elliptical dome resting on an octagonal foundation (the tambour). In his other buildings, he followed the forms of columns, beams and chapters of the Greek-Roman master builders. However, owing to the lack of new ideas, only the crowning dome motif was adopted in the central construction, in the form of the Greek cross or in the basilica in the form of the Latin cross. Instead, the embellishments taken from the Roman ruins were further developed according to classical patterns.

The master builders of the Renaissance fully understood the richness and delicateness, as well as the power of size in Roman buildings, and complemented it with a light splendour. Brunelleschi, in particular, demonstrated this in the chapel erected in the monastery yard of Santa Croce for the Pazzi Family, with its portico born by Corinthian columns, in the inside of the Medici Church San Lorenzo and the sacristy belonging to it. These buildings have never been surpassed by any later, similar building in so far as the harmony of their individual parts is in proportion to the entire building.

Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), who like Brunelleschi was not only a master builder, but at the same time also a significant art historian with his writings About Painting (1435) and About Architecture (1451), was probably the first to articulate this quest for harmony. He compared architecture to music. For him, harmony was the ideal of beauty, because for him beauty meant “…nothing other than the harmony of the individual limbs and parts, so that nothing can be added or taken away without damaging it”. This principle of the science of beauty has remained unchanged since then. Alberti developed a second type of Florentine palace for the Palazzo Rucellai, for which the facade was structured by flat pilasters arranged between the windows throughout all storeys.

In Rome, however, there was an architect of the same standard as the Florentine master builders: Luciano da Laurana (1420/1425-1479), who had been working in Urbano until then, erecting parts of the ducal palace there. He imparted his feeling for monumental design, for relations as well as planning and execution of even the smallest details to his most important pupil, the painter and master builder Donato Bramante (1444-1514), who became the founder of Italian architecture High Renaissance.

Masaccio (Tommaso di Ser Cassai), Madonna and Child with St Anne Metterza, c. 1424. Tempera on panel, 175 x 103 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Lorenzo Monaco, Coronation of the Virgin, 1413. Tempera on canvas, 450 x 350 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Bramante had been in Milan since 1472, where he had not only built the first post-Roman coffer dome onto the church of Santa Maria presso S. Satiro and had also erected the church Santa Maria delle Grazie and several palaces, but had also worked there as a master builder of fortresses before moving to Pavia and in 1499 to Rome. As was common in the Lombardy at that time, he built the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie as a brick building, focusing on the sub-structure. Using ornamentation covering to cover all parts of buildings had been a feature of the Lombards’ style since the early Middle Ages.

This type of design, with incrustations succeeding medieval mosaics, was very quickly adopted by the Venetians, who had always attached much greater value to an artistic element rather than an architectonic structural feature. Excellent examples of these facade designs are the churches of San Zaccaria and Santa Maria di Miracoli, looking like true gems and demonstrating the love of glory and splendour of the rich Venetian merchants. The Venetian master builder Pietro Lombardo (c. 1435-1515) showed that a strong architectonic feeling was also very much present here with one of the most beautiful palaces in Venice at that time, the three-storey Palazzo Vendramin-Calergi.

The architect Brunelleschi had succeeded in implementing a new and modern method of construction. But gradually a sensitivity toward nature, defined as one of the foundations in Renaissance, becomes transparent in some sculptural work of the young goldsmith Ghiberti, which can be found almost at the same time in the Dutch painter brothers Jan (c. 1390-1441) and Hubert (c. 1370-1426) Van Eyck, who began the Ghent Altar. During this twenty year period, Ghiberti worked on the bronze northern door of the baptistery and the sense of beauty of the Italians continued to develop.

Giotto had further developed the laws of central perspective, discovered by mathematicians, for painting – later Alberti and Brunelleschi continued his work. Florentine painters eagerly took up the results, subsequently engaging sculptors with their enthusiasm. Ghiberti perfected the artistic elements in the relief sculpture. With this, he counterbalanced the certainly more versatile Donatello, who, after all, had dominated Italian sculpture for a whole century.

Donatello had succeeded in doing what Brunelleschi was trying to do: to realise the expression of liveliness in every material, in wood, clay and stone, independent of reality. The figures’ terrible experiences of poverty, pain and misery are reflected in his reproduction of them. In his portrayals of women and men, he was able to express everything that constituted their personalities. Additionally, none of his contemporaries were superior to him in their decorations of pulpits, altars and tombs, and these include his stone relief of Annunciation of the Virgin in Santa Croce, or the marble reliefs of the dancing children on the organ ledge in the Florentine Cathedral. His St George, created in 1416 for Or San Michele, was the first still figure in a classical sense and was followed by a bronze statue of David, the first free standing plastic nude portrayal around 1430, and in 1432 the first worldly bust, with Bust of Niccolo da Uzzano. Finally, in 1447, he completed the first equestrian monument of Renaissance plastic with the bronze Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata, the Venetian mercenary leader, (c. 1370-1443), which he created for Padua.

Andrea Mantegna, Mars and Venus, called Parnassus, before 1497. Tempera on canvas, 159 x 192 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Donatello’s rank and fame was only achieved by one other person, the sculptor Luca della Robbia (1400-1482), who not only created the singer’s pulpit in Florence Cathedral (1431/1438), but also the bronze reliefs (1464/1469) at the northern sacristy of the Cathedral. His most important achievement, however, is his painted and glazed clay work.

The works, which were initially made as round or half-round reliefs, were intended as ornamentation for architectonic rooms. But they found a role elsewhere - the Madonna with Child accompanied by Two Angels, surrounded by flower festoons and fruit wreaths in the lunette of Via d’Angelo is a rather splendid result of his creations. As Donatello’s skills culminated in his portraits of men, Robbia’s mastery is demonstrated in his graceful portrayals of childlike and feminine figures – there was nothing more beautiful in Italian sculpture in the fifteenth century.

The demands on the design of these products rose to the extent with which the skills in manufacturing glazed clay work in Italy increased. In the end, not only altars and individual figures but also entire groups of figures were made using this technique, which left the artist complete freedom with regard to the design. Luca della Robbia passed his skills and his experience on to his nephew Andrea della Robbia (1435-1525). He in turn, and his sons Giovanni (1469 until after 1529) and Girolamo (1488-1566) developed the technique of glazed terracotta even further and together with them created the famous round reliefs of the Foundling Children on the frieze above the hall of the Florence orphanage during the years from 1463 to 1466.

The fact that the production of the workshop of the della Robbia Family can still be admired nowadays in many places in Northern Italy demonstrates that the terracotta was not only to the taste of the general Italian public but also to that of the Europeans generally, and that the style was gaining more and more lovers. At the same time we should not forget that no other century was as favourably inclined towards sculptural design as the 15th century.

Thus Donatello’s seeds bore splendid fruit. His two most important students, the sculptor Desiderio da Settignano (c. 1428-1464) and the painter, sculptor, goldsmith and bronze caster Andrea del Verrocchio (1435/1436-1488), continued to run his school in his way of thinking. Especially the latter, who not only created a number of altarpieces, but also became the most important sculptor in Florence. He cast the statue of David, for instance, (c. 1475) and the Equestrian Statue (1479) of the mercenary leader Bartolomeo Colleoni (1400-1475) in Venice. Verrocchio’s style prepared the transition to the High Renaissance.

Domenico Veneziano, The Madonna with Child and Saints, 1445. Tempera on wood, 209 x 216 cm. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

Fra Angelico (Fra Giovanni da Fiesole), The Annunciation, 1450. Fresco, 230 x 321 cm. Convento di San Marco, Florence.

Settignano has left considerably fewer pieces of art than Verrocchio and mainly occupied himself with marble Madonna reliefs, figures of children and busts of young girls. He passed his skills and knowledge on to his most important student, Antonio Rosselino (1427-1479), whose main piece of work is the tomb of the Cardinal of Portugal in San Miniato al Monte in Florence.

Among Rosselino’s students was Mino da Fiesole (1429-1484), who, while originally a stonemason, became the best marble technician of his time and created gravestones in the form of monumental wall graves, and Benedetto da Maiano. Fiesole’s art mainly lived on imitating nature, and was thus too limited to lend variety to his large production.

The second half of the 15th century shows the gradual transition from popular marble processing to the more austere bronze casting, and the two David statues are examples of this. Donatello’s work shows a rather thoughtful David, the other, by Verrocchio, in complete contrast, created in the ideal form of naturalism, a self-confident youth, who is smiling, satisfied with his successful battle, Goliath’s head chopped off at his feet. This smile, which has frequently, but to no avail, been copied by stonemasons has become a trade mark of Verocchio’s school.

Only one artist really succeeded in conjuring this smile onto some of his own work: Leonardo da Vinci, also a student of Verrocchio. The sculptor Verrocchio has to share his fame with the painter Verrocchio, who has only left few paintings behind. Among them are The Madonna (1470/1475), Tobias and the Angel