10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

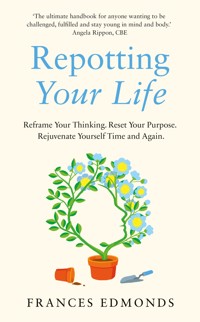

___ Are you ready for something new? If so, you're ready to repot your life. 'Anyone who wants change in their life should buy the book. It's really practical: a step-by-step plan.' Mark Dolan, TalkRadio Self-Development Book of the Week ___ 'Let Frances Edmonds help you pull up those roots and grow some new shoots.' SAM BAKER, Noon In Repotting Your Life, expert 'repotter' Frances Edmonds has created a toolkit with four simple, actionable steps. Whether you're considering a career change or moving to a new place; rediscovering your passions or contemplating any transformation, large or small, this is your essential guide to rejuvenating your life. Step 1 – Know when you need to make a change Step 2 – Identify what makes you happy and what matters to you most Step 3 – Prepare to end one phase of your life and commit to your repotted future Step 4 – Put down new roots and reenergise yourself for your next adventure With verve, wit and wisdom, Repotting Your Life will encourage you to set aside what is no longer working and design a thriving life full of purpose and fresh possibility. ___ 'Really resonates. Keep growing, keep flourishing.' GABBY LOGAN 'The ultimate handbook for anyone wanting to be challenged, fulfilled and stay young in mind and body.' Angela Rippon

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 218

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Dedicated to all my friends at the Distinguished Careers Institute, Stanford: a true fellowship of repotters

‘Repotting, that’s how you get newbloom . . . you should have a plan ofaccomplishment and when that is achievedyou should be willing to start off again.’

ERNEST C. ARBUCKLE, FORMER STANFORD GRADUATE SCHOOLOF BUSINESS DEAN, 1958–1968

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 Potbound

2 Pots and Plans

3 Pulling Up the Roots

4 Bedding In

Conclusion: New Bloom

Acknowledgements

Index

INTRODUCTION

Few occasions are celebrated with such unalloyed optimism as the christening or naming ceremony of a baby. Some time ago, I was privileged to attend one such event and to witness the introduction of a miraculous little girl to her ecstatically grateful extended family. I use the adjective miraculous because without the modern miracle of IVF this particular little girl would never have been born. Events designed to mark life’s major transitions, those time-honoured rites of passage such as christenings, weddings, funerals and milestone birthdays, often serve as catalysts for reflection for those present. And so it was, as the ceremony progressed and I took my turn as godmother to cuddle the new baby, that I began to consider how lucky this little girl was to be born in an era when she may well live to celebrate her hundredth birthday and to enjoy an extra thirty years of lifespan compared with a child born a century ago.

Lucky or cursed? As I started to imagine the course of this fledgling centurion’s life, my optimism became tinged with apprehension. Nowadays, we are all experiencing the seismic changes precipitated by innovations in such fields as information technology and artificial intelligence. What impact might hitherto undreamed of advances in hitherto unheard of areas have on the way this child will have to organise her hundred years? The idea that we might have a job for life has already been relegated to the list of quaintly idiosyncratic expectations shared by previous generations, and our extended life expectancy has rendered the traditional three-phase ‘Learn – Earn – Retire’ model obsolete. The problem we now confront is that society has yet to come up with either an alternative template or the culture and institutions necessary to negotiate the additional phases of our elongated lives. As Carl Jung famously observed way back at the start of the twentieth century, there are no ‘colleges for forty-year-olds that prepare them for their coming life and its demands as the ordinary colleges introduce our young people to a knowledge of the world and of life’. Until communities across the world create solutions, we must rely on our own devices to come up with the answer.

My god-daughter slumbered on, blissfully unaware of the powerful forces at work around her, a modern-day Sleeping Beauty. If only, I mused, like the fairy godmother of the Grimms’ celebrated fairy tale, I could grant her some gift to help her negotiate the vagaries and vicissitudes of an increasingly volatile twenty-first century. Contemporary readers may raise a wry smile when they consider the gifts deemed desirable by the Grimms’ bevvy of fairy godmothers: beauty, wit, grace, dance, song and goodness. Essential attributes though these might well have proved for aspiring young women of previous centuries, they will hardly cut the mustard for anyone hoping to survive and thrive throughout the twenty-first. Due to a series of unforeseen developments and plot twists, Sleeping Beauty is cursed to sleep for a hundred years. If today’s Sleeping Beauty is to be blessed to live for a hundred years, she is going to need a very different skill set to help her make the most of this extra time in the face of all the challenges of an ever-more unpredictable world. As we celebrate her christening, it strikes me that this is merely one of the very many new starts that this baby will have to manage during her recently embarked upon life.

Much further along the longevity spectrum, and rapidly approaching the springtime of my senility, I often find myself looking back over a lifetime that has witnessed not only massive societal changes but also many profound, sometimes painful, personal transitions. According to the great British statesman Sir Winston Churchill, success is the ability to move from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm. On the basis of that very generous yardstick, I am comforted to think of my own biblically allotted lifespan as the most tremendous success. Over a period of almost three score years and ten, I have moved from modern linguist and international conference interpreter, to writer and broadcaster, to keynote speaker, to parent and homemaker, to building contractor and business development networker, to longevity and well-being research fellow and cross-generational mentor – the list is still a work in progress. Transitions involving the challenges of a new job, the excitement of a new relationship or the demands for personal growth required by responsibilities such as parenthood or mentorship may prove exhilarating if, occasionally, exhausting. Working your way through the various phases of truly transformative transitions is usually a difficult and stressful process. The relief unleashed by sighting that metaphorical light at the end of the tunnel may blot out the pain endured to get there. It is, however, useful to remember what and how you were feeling when eventually the catalyst arrived that propelled you to ‘start digging’.

My own most recent alert came when I was watching a gardening programme. The presenter moved from the joyous profusion of colours, shapes and textures in his herbaceous borders to focus on a sad little specimen lurking disconsolately in a pot by his shed. For the benefit of the camera, he picked it up, the better to display its full wretchedness to the viewers at home. The poor plant seemed embarrassed by this sudden intrusion and a few of its remaining leaves fluttered lethargically towards the ground. The presenter was undeterred. Yanking the plant from the pot by its spindly stem, he pointed to a knotted tangle of roots circling endlessly round and round and interwoven into an impenetrable, tightly knitted ball. ‘This is what happens,’ he observed, ‘when a healthy plant is neglected and can’t find enough sustenance when it’s trying to grow. It’s now so weak that it can’t send out roots to nurture itself from the surrounding environment. This plant is potbound!’ He paused and stared mournfully into the camera for full dramatic effect. ‘Unless it’s repotted soon, this plant is going to choke itself to death.’

I had to restrain myself from cheering out loud: not at the potential fate of this poor plant, but at my own sudden insight of incandescent lucidity. In one short sentence, the presenter had diagnosed the malaise from which I had been suffering. Mr Gardening Guy had nailed it. This was what was wrong with me! For quite some time, I’d been assailed by this nagging feeling that my own increasingly pointless efforts to flourish were going around in circles. The commitments, pleasures and pastimes that once I had enjoyed no longer seemed to engage or sustain me. Call it existential angst or ennui, or call it simply tired-all-thetime fatigue, but the more I struggled to ignore whatever it was, the worse the symptoms became. It was like fighting against the constraints of a straitjacket. Suddenly, the diagnosis implied was beyond all reasonable doubt. I was potbound. I’d been living in an environment that had worked well enough, but now I was feeling stifled by it. Not only was it stunting my growth, it was jeopardising my well-being. Hence the insistent sense that something was not quite right. It was clear that the time had come to extract myself from my current situation and to set out in search of a new, more propitious environment. It was equally clear that no convenient Mr Gardening Guy was ever going to organise my own repotting for me. However tough it might prove, and however much support I might garner along the way, this was a process of self-renewal that I’d have to work out for myself.

This realisation that I needed to ‘repot’ would soon be directing my next steps, the decisions I would make and what I wanted for my future. What I learnt along my journey of repotting – a journey that would take me to a whole new country and an undertaking full of possibility and growth – also offers, I hope, a useful new model for navigating the increasing number of transitions that we are all called upon to make throughout life in the modern world. And so my gift to my god-daughter, and to anyone embarking on a new stage in life would be an understanding of how best to master the challenging and often daunting process of moving on and branching out. My gift would be proficiency in the art of ‘repotting’.

How do you know when you are potbound?Is repotting the best solution for you?

First of all, it’s important to understand that the potbound predicament is no respecter of age. The very tendrils that you have yourself grown into the soil around you can stifle you at any stage of your life: young, old, middle-aged, retired, at the peak of personal achievement or at the apogee of a professional career. For many people, the descent into becoming potbound is a perniciously gradual process, a continuous drip-drip accumulation of apparently minor issues. Although the realisation of the full extent of potbound damage may come as a sudden shock, rather like the dramatic demise of a majestic oak that no one realised was riddled with rot, it is not the focus of this book to deal with the aftermath of unexpected, cataclysmic events such as those occasioned by life-changing accidents or injuries. Although such tragic reversals may generate similar feelings and require similar solutions, the potbound phenomenon is a malaise that creeps up over time. Often the damage being done is so stealthy and surreptitious that you’re unaware of the harm being wrought and fail to spot the well-camouflaged signs until they’ve made quite serious inroads. You may, for instance, have sought refuge in sticking your head in the sand and successfully managed to ignore the fact that your innate tendency to grow and develop has somehow been arrested. Or perhaps you’ve never had the time to notice that instead of continuing to flourish and blossom, you’ve actually started to wilt and wither.

Of course, it’s easy to identify that things aren’t working when you’re dealing with inanimate objects. Even dug in deep beneath the most substantial sand dune, most of us would still recognise when the boiler has exploded, the laptop has crashed or that we’ve just dropped our smart-phone in a puddle, smashed the screen, and reversed over it with the car for good measure. It’s far more difficult to establish that there’s something seriously amiss when we’re considering a lifelong career, an intimate relationship or some other profoundly personal situation. When we find ourselves confronted with a complex set of circumstances, it’s often hard to separate what’s important and what’s not.

If you struggle to get out of bed to go to work one grim winter’s morning, does that immediately mean that you should call it a day and quit your job? If your partner squeezes toothpaste from the middle of the tube, cracks his knuckles while watching television, or consistently taps the top of his boiled egg in that irritating fashion, does that necessarily warrant a call to the divorce lawyer? Maybe. Maybe not. Perhaps none of these seemingly nebulous niggles would be sufficient in themselves to trigger a dramatic change of direction, but they might gradually lead you to a tipping point, or alert you to a more fundamental issue that you haven’t yet admitted or identified. It’s not the knuckle-cracking or the murderous urges in themselves, but it’s the way they add up to a dangerous accumulation of repressed feelings.

Why are we so adept at covering up and ignoring our instincts? Perhaps part of the problem is that we’re conditioned to resist the idea that things aren’t working. From an early age we’re drip-fed the notion that, if we try hard enough, we’ll eventually overcome the problems that life throws at us. We live in a society that rightly prizes resilience, grit and perseverance. Just like previous world-war generations, we’re exhorted to pack all our troubles in our old kit bags and smile, smile, smile. Staying power, the stuff of true champions, is justifiably lauded. In such a competitive environment, no one feels comfortable looking like a quitter who hasn’t given 100 per cent commitment to the job in hand. None of us wants to fall at the next hurdle, but how do you know when you’re flogging a dead horse?

Herein lies the rub. If you don’t learn how to ask yourself the right kind of questions, you’ll never have a hope in hell of coming up with the right kind of answers, and you risk finding yourself climbing to the top of a very impressive ladder only to discover that it’s up against the wrong wall. Or that you’ve ploughed a wonderfully straight furrow, but it’s in the wrong field. Feel free to dream up a suitably compelling metaphor to cover your own particular situation, but you get the idea: fail to question your own feelings, motivations and behaviours and you’re soon on the path to being potbound.

So how do we start framing the kind of questions that might deliver answers best geared to ensure our overall wellness, well-being and sense of purpose? I believe the right questions involve the heart, as opposed to the head, far more frequently than we imagine. Too often our conscious selves elect to ignore our unconscious wisdom, often at the expense of physical and mental health. Sometimes we may even be aware of this clash between our intellectual and emotional selves but we make the mistake of brushing aside our gut feelings and pushing on regardless. Far more frequently we simply fail to recognise what our heart is trying to tell us. The writing might be on the wall, but we haven’t acquired the emotional literacy to read what the message says. In the absence of some handy key to decipher the Rosetta Stone of our innermost feelings, we could be mired in our potbound predicament forever until we learn to crack our own code.

LOOK FOR PHYSICAL AND BEHAVIOURAL CLUES – IN YOURSELF AND ALSO IN OTHERS

It may seem counter-intuitive but, if we are to develop this emotional literacy, it is worth paying attention in the first instance to physical clues. Sometimes the body expresses what the mind represses, so don’t discount the possibility that a physical symptom could be a sign of feelings that you are barely aware of. If you feel the urgent need to sink a bottle of wine or polish off a litre of Ben & Jerry’s after every phone call with your mother, there are probably more forces at work than those of mere physical cravings. Ask yourself, before you pass out clutching the Pinot Grigio, face down in the family-sized tub of Cookie Dough, are your own eating, drinking and sleeping habits pointing to unresolved or maybe even unrecognised problems? Warning signals from skin eruptions to changes in heart rate to tense body language can also serve as powerful indicators that something is amiss. A friend of mine grew so depressed over her distressingly disfiguring skin complaint that she seriously considered giving up the work she loved due to what she assumed was stress. As part of her responsibilities, she was often obliged to deal with a certain British television and radio personality whose well-publicised record on charitable fund-raising had resulted in his being honoured by a knighthood. Given the star’s status and celebrity, my friend found her attempts to avoid being in the same room as him increasingly difficult to justify. It was only after his death, when it transpired that this widely fawned-upon knight of the realm had been operating with impunity for many years as one of Britain’s most prolific sex offenders, that she finally realised that this man had been responsible – literally – for bringing her out in a rash.

Apart from observing physical clues, try also drilling down into your habitual patterns. In the crucially restorative area of sleep, for example, most of us will have experienced those long dark nights of the soul spent tossing and turning and wrestling with genuine and recognised worries. Others will have spent endlessly unproductive hours conked out from apparent exhaustion but, in reality, trying to escape from unresolved issues by resorting to chemical oblivion. From hair loss to high blood pressure to non-specific back pain – a cursory glance at any agony aunt column provides telling insights into the range of physical symptoms that are often pointing to deeper emotional issues.

Sometimes the clues to your potbound status are behavioural rather than physical, and they can be harder to identify – at least in yourself. Before you try to spot any warning signs in your own behaviour, it’s helpful to train your eye by watching the behaviour of total strangers. I’m not suggesting that you start scrutinising people with the obsessive attention of some swivel-eyed psychopath, just that you discreetly try spotting the clues. One evening, around the time of my own potbound epiphany, I was sitting in my favourite local Italian restaurant and observed a couple out for dinner together. The moment the man was seated, he smacked his iPhone down on the table. The woman’s eyelids flickered. Without missing a beat, she saw his iPhone, raised him a Samsung Galaxy and threw in a mini iPad. Before long, he was ostentatiously ogling the waitress’s legs. She countered by giving the wine waiter’s arm an overly familiar pat. I followed this elaborate quadrille of active indifference for over an hour. Neither of them could have spoken more than a dozen words to the other as they parried their way through their respective plates of pasta. From what I could make out, there was neither the energy nor the animus between them to suggest the aftermath of a blazing row. It was simply that these two attractive, ostensibly successful people were wholeheartedly engaged in the process of passive-aggressively irritating each other to death.

Perhaps these two strangers were aware of their unhappiness but were too terminally potbound even to be bothered to break up, or perhaps like so many of us they had no idea what was actually going on. The point is that the best way to recognise yourself as potbound is to identify the spectrum of potbound symptoms playing out in other people. Many of you will have consulted the burned-out physician too exhausted to diagnose a decapitation. He’s scribbled out your prescription on his pad before you’ve even finished describing your symptoms. Or perhaps you’ve come across the poor end-of-her-tether mother so frazzled that she forgets to pick up her kids from school and is constantly trying to microwave oven-ready meals in the top rack of her dishwasher. She’s so overloaded with other people’s wants and needs that she has nothing but debilitating disregard for herself. Or perhaps you have worked with one of those complacent or bully-boy bosses who stubbornly refuse to stand aside, so smugly self-satisfied with their long-gone successes that they are unable to see the threat of competitive disruption that’s about to destroy their organisations. Witness the slew of failed Pol Potbounds in the British retail business!

Once you start looking for examples of potbound behaviour, and analysing the symptoms, you’ll gradually become more and more proficient at identifying them in yourself. Perhaps you begin to recognise those constant sighs of world-weary exhaustion as signs of about-toblow frustration? You ask yourself why it is that you’re always snapping at the kids. Maybe you begin to realise that you’re forever watching the clock at work, or that you’re constantly swearing at inanimate objects and arguing with the radio. Perhaps you question whether your ostensible diligence in working at weekends is in reality a way of avoiding your partner. And was it really just an accident this morning when you reached out and whacked him on the nose instead of hitting the snooze button? You may find yourself defaulting to knee-jerk negativity and grumpy responses, or you may realise that you’re simply trundling along, somehow managing to survive another godawful day without the life-enhancing seasoning of the merest dash of joie de vivre.

Despite the tsunami of smart watches, apps and fitbits widely available nowadays, there still don’t seem to be any high-tech solutions on offer designed to track the most important things in life. As far as I can see, there’s no app around that tells you that you’re behaving like a jerk, that you shouldn’t be so thin-skinned, or that you really ought to try and lighten up a little. So how can you increase awareness of your own behaviours? How can you detect any potentially potbound signals? When you’re dealing with deeply personal issues, it seems that only low-tech solutions will do. I’ve always found that keeping a diary, quite apart from fitting Oscar Wilde’s bill of ensuring that there’s always something sensational to read in the train, also provides a rich seam to mine, unearth and identify cause-and-effect patterns.

If you can find the time to keep a daily journal, however perfunctory, you’ll start to recognise recurrent themes and learn how to identify when and why they happen. Imagine, for example, that you’ve been called out for snapping at your work colleagues. You didn’t even realise that you were being stroppy but, when you look back over your journal, you notice that every time you embark on an undertaking that interests you, you’re somehow dragooned into dealing with other colleagues’ pressing issues and end up doing a suboptimal job on your own pet project. Suddenly you understand not only why you’re irritated at work but also why, when you return home to find your children’s trainers scattered untidily in the hall, you explode with an outburst out of all proportion to the misalignment of a few random Nikes.

For me, a journal provides a cathartic lightning rod for channelling all manner of inchoate feelings. It’s a useful structure for identifying patterns and explaining my otherwise often inexplicably bad behaviour. And it’s also a secure repository for offloading the arrant drivel that’s constantly swirling around in my head. Many people I know learn how to interpret their emotions and the patterns at play in their lives by paying attention to their decisions, behaviours and reactions in all sorts of different situations. If you only ever eat pizza, or play the same old music, or still wear that purple eyeshadow some cruel clown suggested was hip way back in the 1960s, you might want to ask yourself whether these are actively satisfying decisions or whether your developmental clock has simply stopped. Even the amount of pleasure you now derive from the hobbies and pastimes that you once enthusiastically engaged in – whether your interest lay in art, music, craft, cooking, travel, exercise or sport – may alert you to when you’re in, or when you’re close to falling into, potbound territory.

EXAMINE YOUR PAST

Another way to diagnose ourselves as potbound is to look at times in our past when we have been unhappy – and to attempt a retrospective diagnosis. This can be especially useful as a way of identifying our own particular triggers and warning signals. When I look back over my own life, for example, I can now see all sorts of telltale signs that I didn’t recognise at the time – particularly from the point at which I entered the world of work. Although my childhood and adolescence could hardly be described as a remorselessly merry experience, I found that school and university at least provided roadmaps that were clear and easy to follow. They provided stages, scores and targets that were reassuringly simple to understand, if often challenging to achieve. Like many children of my generation, I was given to believe that how my life panned out would be down to intelligence or effort – ideally and most successfully by a combination of both. On this basis, I understood what I was supposed to be doing and generally felt that I was making progress if I managed to do it. The expectations and goals of the education system were equally simple to comprehend: do the work, pass the exams, party as hard as you can with any residual time available. Wash – Rinse – Repeat Cycle.

Work, however, was an infinitely more complex ball game. Not only did metrics for meaningful development in the workplace seem more difficult to track, but the right track itself was not always easy to identify. After I graduated with a degree in modern languages, my first job was as an international conference interpreter. The task of a simultaneous interpretation is both physically and mentally taxing: you’re called on to function as a multilingual peace-keeping force conciliating a war of words being constantly waged in your head. The process involves tuning in to someone speaking in one language, assimilating their content, tone and nuances, and then converting the entire meaning and message almost instantly into another language. Get it wrong, and all hell breaks loose! For me, gaining proficiency in the profession involved a steep learning curve and most of the time my brain ached but, from the outset, I loved the work, its challenges and the vibrant community and camaraderie associated with it. Over a period of fifteen years, I was working all over the world for many major international organisations, including the European Union, the United Nations and the world’s leading heads of state and government at their annual World Economic Summits.