Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Richard III, King of England from 1483 to 1485, made good laws that still protect ordinary people today. Yet history concentrates on the fictional hunchback as depicted by Shakespeare: the wicked uncle who stole the throne and killed his nephews in the Tower of London. Voices have protested during the intervening years, some of them eminent and scholarly, urging a more reasoned view to replace the traditional black portrait. But historians, whether as authors or presenters of popular TV history, still trot out the old pronouncements about ruthless ambition, usurpation and murder. After centuries of misinformation, the truth about Richard III has been overdue a fair hearing. Annette Carson seeks to redress the balance by examining the events of his reign as they actually happened, based on reports in the original sources. She traces the actions and activities of the principal characters, investigating facts and timelines revealed in documentary evidence. She also dares to investigate areas where historians fear to tread, and raises some controversial questions. In 2012 Carson was a member of Philippa Langley's Looking For Richard Project, which provided important new answers from the DNA-confirmed discovery of the king's remains. Her involvement in Langley's Missing Princes Project, with its international research initiative on the 'princes in the Tower', has now informed her revelatory extra chapter.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 717

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

RICHARD III

THE MALIGNED KING

In memory of Isolde Wigram,

gallant co-founder of the present day Richard III Society, and champion of the standpoint that the ‘princes in the Tower’ were not murdered there, nor killed by Richard III.

‘The purpose and indeed the strength of the Richard III Society derives from the belief that the truth is more powerful than lies – a faith that even after all these centuries the truth is important. It is proof of our sense of civilised values that something as esoteric and as fragile as a reputation is worth campaigning for.’

HRH The Duke of Gloucester, KG, GCVO, Patron

Also by Annette Carson

Flight Unlimited (with Eric Müller)

Flight Unlimited ’95 (with Eric Müller)

Flight Fantastic: The Illustrated History of Aerobatics

Jef f Beck: Crazy Fingers

Welgevonden: Wilderness in the Waterberg

Richard III: A Small Guide to the Great Debate

Finding Richard III: The Official Account of Research by the Retrieval and Reburial Project (with J. Ashdown-Hill, D. Johnson, W. Johnson and Philippa Langley)

Richard Duke of Gloucester as Lord Protector and High Constable of England

Camel Pilot Supreme: Captain D.V. Armstrong DFC

Domenico Mancini: de occupatione regni Anglie

As Publication Project Manager:

Arthur Kincaid, ed., The History of King Richard the Third by Sir George Buc, Master of the Revels (1619) 3rd edn

First published 2008

This revised and updated edition first published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL 50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Annette Carson, 2008, 2009, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018, 2023

The right of Annette Carson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75247 314 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

1 Poisoned?

2 The Politics of Power

3 Plot and Counter-Plot

4 A Shadow over the Succession

5 Battle Lines are Drawn

6 ‘This Eleccion of us the Thre Estates’

7 Witchcraft and Sorcery

8 Dynastic Manoeuvrings

9 The Disappearance of the Princes

10 Bones of Contention

11 The October Rebellion

12 Brave Hopes

13 Barbarians at the Gates

14 Postscript

15 Reappearances

Appendix

Notes and References

Select Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Plates between pages 240 and 241

1. Richard III facial reconstruction by Professor Caroline Wilkinson (Colin G. Brooks)

2. Edward IV, panel portrait (By kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London)

3. Queen Elizabeth Woodville, panel portrait, Ripon Cathedral

4. Middleham Castle

5. Baynard’s Castle

6. Interior of Crosby Hall

7. Exterior of Crosby Hall in the 1840s

8. Abbey and Palace of Westminster in 1537 (TopFoto/Woodmansterne)

9. Richard III and Queen Anne Neville, stained glass by Paul Woodroffe

10. Richard’s signet letter of 29 July 1483 (The National Archives)

11. Richard’s signet letter of 12 October 1483

12. Parliament Roll known as Titulus Regius (The National Archives)

13. The urn placed in Westminster Abbey by Charles II

14. ‘Perkin Warbeck’, probably by the herald Jacques le Boucq (Visages d’Antan, Le Recueil d’Arras – éditions du Gui 2007)

15. Tower of London, early twelfth century (Museum of London)

16. Forebuilding and stairs, c.1360 or later (Anthony Pritchard)

17. White Tower, small doorway with plaque (Jane Spooner)

18. Tower of London, copy of 1597 survey

19. Elizabeth of York, panel portrait (National Portrait Gallery, London)

20. Manuel I of Portugal, by Nicolau Chanterêne (Luís Pavão/IGESPAR, I.P.)

21. Joana of Portugal, attr. Nuño Gonçalves (Museu de Aveiro/IMC)

22. The Bosworth Crucifix (By kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London)

23. Richard III falls at Bosworth, stained glass by Christopher Webb

24. Richard III as warrior king, statue by James Butler RA

25. Richard III armed and mounted, model by Roy Gregory

26. The Great Seal of Richard III

27. Richard III’s full achievement of arms (Andrew Stewart Jamiesonwww.andrewstewartjamieson.co.uk)

Text illustrations

Table 1: Royal Houses of York and Lancaster (simplified)

Table 2: Houses of Tudor and Beaufort

Signatures of Edward V, Gloucester and Buckingham

Map: The Low Countries c.1483

Detail, south elevation of the White Tower

John Webb’s plan

Lawrence Tanner’s plan

Lower jaw-bone of older skull in the urn

Table 3: House of York – the succession after Richard III

Table 4: Descendants of Edward III in 1483 other than Royal Houses of York and Lancaster

Margaret of York (author’s collection)

Maximilian I (author’s collection)

Extract from Gelderland MS, c.1493 (Gelders Archief )

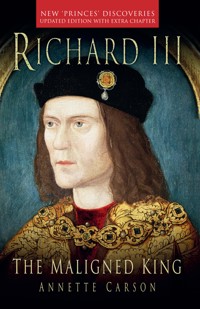

Cover illustration

Probably the earliest surviving version (c.1510) of a portrait from life. Distortions were added to all known portraits, including the grimly clenched mouth overpainted on this before restoration in 2007. (Society of Antiquaries of London ref. LDSAL 321)

All images not otherwise attributed are © Geoffrey Wheeler, whose invaluable picture research is gratefully acknowledged.

Table 1: Royal Houses of York and Lancaster (simplified)

Preface

This book is not a biography of Richard III. It is a highly personal analysis of the more controversial events of that king’s reign, starting with the death of his predecessor and brother, Edward IV, in 1483.

At the outset my aim was to research, not to vindicate. However, in the course of my progress many surprising things became evident. Among them was the determination of most historians to place negative interpretations on Richard’s actions, while applauding the career of deceit and underhandedness that characterized his nemesis, Henry VII.

Thus, the thrust of my writing gravitated towards Richard’s defence. I do not claim to have found unequivocal answers; but I have delved as deeply as possible into particular topics that seem to need exposure to the clear light of day, seeking for a kernel of truth under layers of misinformation. Sometimes I offer conjectures, mine and other people’s, that disturb long-established comfort zones. I offer them in support of a truth too often overlooked: we do not know as much as we are led to think we know. Context is everything, especially with equivocal events – for example speculation around Edward IV’s death and its date. I see a clear parallel with the way theorists have interpreted historical records over the centuries to build their case against Richard III.

Although my main interests lie in the oft-ignored nooks and crannies of history, let me emphasize that this book is written for the ordinary reader – anyone who knows a little about King Richard III of England and would like to know more. A strand of narrative runs through it all which ensures that we keep following the story of Richard III’s reign as it unfolds.

Above all you will find none of the sweeping judgements so loved by historians (good, evil, prudent, ambitious, pious, hypocritical, etc.). Richard was a man of his times and a king of his times, concerned with matters beyond the experience of any twenty-first century commentator.

Current academic orthodoxy concedes that Richard III was probably not the monster of Tudor mythology, but assumes the rationale behind his seizure of the crown must have been a fiction; that being a usurper, he must have had his two nephews murdered because that was what usurpers did; and that their murder was, on balance, confirmed by the bones inurned in Westminster Abbey by Charles II. These are, inter alia, assumptions that I challenge in these pages.

Those who cast Richard III as an unprincipled usurper have done so because they have made judgements and drawn conclusions: no concrete evidence exists to convict him. But academic orthodoxy is a tough nut to crack, and is passed on to each new generation of scholars.

If Richard III is to be assessed, let it be on his overall conduct as a sovereign. When it comes to matters in which he had some control, such as legislation brought before Parliament, his record has been recognized over the centuries as significant and enlightened. By contrast with kings before and after him, he indulged in no financial extortion, no religious persecution, no violation of sanctuary, no burning at the stake, no killing of women, no torture or starvation and no cynical breach of promise, pardon or safe-conduct in order to entrap a subject. Anyone who has been led to believe that Sir Henry Wyatt was tortured by Richard III is recommended to read my comprehensive refutation of that myth (see www.richardiii.net/downloads/wyatt_questionable_legend.pdf ).

After Richard’s death the story of the murderous, tyrannical king was fostered by his killers and became part of English legend. Encouraged by a climate of Court approval, chroniclers vied with each other to heap venom on his memory and devise horror stories to add to his constantly growing list of crimes. In their ignorance they jeered at his physical form and heaped on him an assortment of grotesqueries, believing that an ill-formed body was the outward manifestation of an evil mind. This fictitious Richard III became the subject of one of Shakespeare’s most alluring melodramas. Shakespeare had little need for invention: he found the entire artifice already crafted to perfection by the Tudor chroniclers.

By contrast, the scant information dating from pre-Tudor times is generally found in letters and jottings, cursory government records, or a few isolated narratives. The unreliability of the latter is amply demonstrated in the works of John Rous, a Warwickshire priest who fancied himself a chronicler. Rous generously left to posterity two opposite views of Richard III: the first, composed during his reign, admiring and complimentary; the second, composed after his downfall, hostile and vituperative.

The example of Rous illustrates how important is familiarity with the source material when it comes to forming an independent opinion. Here, therefore, you will find an unusual approach: an Appendix is provided which contains a list of the principal sources used, together with notes about factors which may be relevant to the credibility of the writers. These include dates; partisanship; motivation; whether answerable to a patron; whether facts were accessed at first hand and, if at second hand, the reliability of the likely informants. The notes are mine, taking into account analyses by historians and academics.

In the last resort the issue of credibility is a matter for the individual to determine, and I cannot substitute my judgement for yours. Nor is it my intention to provide scholarly analyses of sources. As an author I have made choices as to which are reliable enough to be quoted in evidence, and which are, to a greater or lesser extent, dubious. If a source is so biased that it must, in my opinion, be read with inordinate care and circumspection, or if written by a person too far distant in time or location from the events he purports to describe, then it will be mentioned only if there is some exceptional reason for doing so – and then with a health warning attached.

I have taken as my main sources two narratives that were written by people who were present when most of the events they describe took place. The first is an intelligence report produced for his foreign master by an Italian cleric, Domenico Mancini, after visiting London in 1483. The second is also probably the work of a cleric, an anonymous Englishman this time, who in 1485–6 related his version of recent secular affairs while contributing to the ongoing Chronicle of the Abbey of Crowland; a man who seems to have enjoyed a degree of intimacy with the centres of political power. Even these sources are marred by identifiable errors and partisanship, but they are undoubtedly the best we have.

A third important writer, Polydore Vergil, produced a gigantic history of England in the early sixteenth century at Henry VII’s behest. Vergil’s treatment of Richard suffers from the same drawbacks, with a few new ones into the bargain: he writes at a distance of over two decades after the events; he is an Italian with no personal knowledge of Richard III’s England, so his material is gleaned through informants; plus he always has to keep an eye on the interests of his patron.

Nevertheless, Vergil made manful efforts to get factual information, both written and oral. Regrettably, commentators have given equal credence to writers of his century with far less claim to credibility, whose fantastic stories have been believed and retold in all seriousness. In this book the reader will find scant place for such works of imagination, into which category Thomas More’s History of King Richard the Third is firmly relegated.

Though written more than a generation after the event, and crafted as a literary piece with an underlaying didactic message, More’s apologue is still trusted and quoted by experts up to the present day. Unfortunately, because so much of popular tradition about Richard derives from More, it has not been possible to ignore him altogether. In this connection it is instructive to consider who might have been his informants (see Appendix).

Such evaluation of sources is at the heart of all scholarship, and routinely gives rise to disagreements among historians. Unsurprisingly, opinions are polarized as to the relative value of Thomas More’s imaginative ‘history’. At one end of the scale we have David Starkey of television fame, who places utter faith in it as the work of a reliable historian – give or take a few blunders – while at the other end is Alison Hanham, author of an illuminating survey of Richard’s early historians, who labels it a ‘satirical drama’. See also a seminal paper, ‘influential in the development of a critical trend’, by Arthur Kincaid, ‘The Dramatic Structure of Sir Thomas More’s History of King Richard III’, Studies in English Literature 1500–1900: Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama (Rice University, Houston, Texas), Vol. XII, No. 2, spring 1972, pp. 223–242, twice anthologized.

Of course, professional historians tend to see it as their own peculiar and especial prerogative to evaluate sources. Charles Ross, in his 1981 biography of Richard III, speaks for many of his colleagues when he denigrates ‘revisionists’ for picking and choosing which portions of sources they believe. ‘For example,’ he says in his Introduction, ‘Polydore Vergil, as a Tudor author corrupted by [Archbishop John] Morton, cannot be relied upon, and yet becomes an acceptable authority when he reports a general belief that the princes were still alive.’

Nevertheless Ross reserves for himself exactly this right to pick and choose. He thoroughly approves of Domenico Mancini (thereby dismissing observations on the reliability of Mancini by several noted historians, including Rosemary Horrox: see Richard III: A Study of Service). However, when dealing with reportage concerning Edward IV’s execution of his brother Clarence, Ross actually prefers Thomas More’s accusation that ‘Richard was privately not dissatisfied’, while discounting Mancini who claims that Richard was grieved by it. He takes the same line in his biography of Edward IV, not only discounting Mancini’s report, but dismissing Polydore Vergil and the Crowland chronicler as well, both of whom, he admits, ‘lay the blame firmly on the king [Edward] and do not mention Richard at all’.

While Professor Ross has every right to discriminate between the conflicting possibilities offered in various sources, his preference for More as opposed to all the others is surprising. But, if Ross can choose what he wants to believe then so, too, may lesser mortals.

In writing this book I have made use of Charles Ross as well as innumerable other writers and historians down the years whose painstaking researches have provided a fund of knowledge about Richard III, his life and his times, ready to be plundered by the likes of me. If I take issue with some of their pronouncements it is in a spirit of professional cut-and-thrust, and does not diminish my appreciation and respect for their work.

I have also consulted many advisers who have kindly found time to encourage and guide me through the many pitfalls that await the unwary.

Chief among them I must thank the late John Ashdown-Hill, our foremost authority on Lady Eleanor Talbot. I am indebted to him for allowing me to read a pre-publication manuscript of Eleanor, the Secret Queen, and for his kindness in reading my own manuscript and suggesting improvements, all of them valuable. My thanks also go to Marie Barnfield for much appreciated advice for the 2009 paperback edition.

I am equally indebted to Geoffrey Wheeler for suggestions and encouragement, for his tireless work on illustrations and for meticulous research and advice concerning the architecture of the Tower of London.

My thanks go also to Richard E. Collins, whom I regret I have not been able to trace. Whether or not his research into the death of Edward IV contains a germ of likelihood, it certainly opens up vistas of interesting conjecture.

I have received unfailing help and support whenever I have requested it from members of the Richard III Society, without whom this book would not have been possible.

Finally, a personal thank you to David Baldwin, Rebekah Beale, Lesley Boatwright, Carolyn Hammond, Peter Hammond, William E. Hampton, Lt-Col. Bernie Hewitt, Keith Horry, Edward Impey, Michael K. Jones, Philippa Langley, Joanna L. Laynesmith, António S. Marques, Wendy Moorhen, Piet Nutt, Geoffrey Parnell, Adrian Phillips, Sandra du Plessis, Pauline Harrison Pogmore, Christine Reynolds, Jane Spooner, Phil Stone, Jane Trump, Carolinne White, William J. White and Andrew Williams. It goes without saying that I take entire responsibility for what lies within these pages; I have attempted to keep successive editions amended where flaws have been found, and updated to include new material as it emerges, including my own new translation and analysis of Domenico Mancini’s crucial report de occupatione regni Anglie.

Chapter 13 of the 2013 edition added the discovery of Richard III’s lost grave and the rescue of his mortal remains for dignified reburial, a project in which I was privileged to participate.

In this latest edition of 2023 we now have a new chapter 15, thanks to the dedicated work of Philippa Langley leading an international team of researchers in her Missing Princes Project. So far we have just two documents from a potential treasury of probative resources in overseas records, hitherto ignored because of historical certainties that the sons of Edward IV inevitably died a murderous death. Given that it was as long ago as 2008 that I first published my suggestions about the princes’ likely survival, it is gratifying to know they still stand today.

1

Poisoned?

In the spring of 1483, King Edward IV of England was no longer the man he had been. His figure, once magnificent, was now corpulent – so much so that he could no longer ride at the head of his troops.

An outstanding military leader in his youth, he had intended personally to command a great campaign against the Scots in the summer of 1481, but when the time came to lead his army northwards, his fitness failed him. He then resolved to command an invasion in 1482. Eventually he abandoned the effort.

Edward had become a glutton, a drinker and a carouser in wanton company. In the censorious words of the chronicler of Crowland Abbey, he was ‘a gross man’, ‘addicted to conviviality, vanity, drunkenness, extravagance and passion’, ‘thought to have indulged too intemperately his own passions and desire for luxury’.

However, although unfit and overweight, Edward was not a sick man. Historians were led to believe his health was deteriorating by an apparently contemporaneous report to the city fathers of Canterbury in 1482, but this has been identified as an editorial interpolation.1 Indeed, the Crowland chronicler’s observations of Court revelry that last Christmas, with the king cutting a dash in clothes of a brand new fashion, indicate nothing of any sickness.

In a recent parliamentary session he had also committed himself to a war of retribution against France: not the action of someone who felt his health was failing. In this context the Crowland chronicler describes him as a ‘spirited prince’ and ‘bold king’.

Yet soon after Easter, Edward suddenly died a few weeks short of his 41st birthday. We hear details of his death from a wide variety of writers, few of whom are reluctant to offer ideas as to the cause. Writers after about 1500 are unlikely to be reliable; some of their wilder suggestions include over-indulgence in wine, an excess of vegetables, an ague brought back from France, and an attack of melancholy or chagrin.

According to the Crowland chronicler, mentioned above, the king took to his bed about Easter. He was affected ‘neither by old age nor by any known kind of disease which would not have seemed easy to cure in a lesser person’. This cleric, writing in 1485, is the most authoritative source we have, being an official who was involved in Edward’s government. Easter Sunday fell on 30 March; however, his date of death cannot be known with certainty. It was given out, apparently, as 9 April, but no one could have known the true date aside from those present at his deathbed: probably his wife, her London-based family, and members of their inner circle.

The Italian cleric Domenico Mancini, a visitor to London in 1483, said the king died from catching a chill while in a boat on a fishing trip. Mancini did not enjoy the Crowland chronicler’s inside knowledge, nor, presumably, did he speak English. He had been sent to report on events in England by his patron, Archbishop Angelo Cato, a man of influence in the Court of Louis XI of France.

A different opinion was offered by another of Louis’s courtiers, Philippe de Commynes, writing probably in the 1490s: Edward fell ill and died soon afterwards, he said, ‘some say of a stroke’.

With these and a multitude of other theories to choose from, no one was sure what caused the death of this bloated but otherwise healthy king.

Then in 1996 Richard Collins of the University of Cambridge published a short treatise outlining his suspicions that Edward IV might have been poisoned.2

In his view, Edward’s death had been too easily accepted as inexplicable. Writing from a substantial medical background, Collins considered the cause of Edward’s death ought to be recoverable: ‘I take it as self-evident that death occurs invariably through an assault on a mechanical organism with predictable results; and that, after it has happened, the cause of death may be deduced from that pattern of results.’ He therefore set about investigating what was known about the patient, and the manner and circumstance of his demise.

Examining the story of the chill while boating, Collins observed: ‘since the king certainly couldn’t have indulged in such frivolity during Holy Week, the latest this trip could have taken place was 22 March … If true, it means he hung around in a fever for ten days, without treatment, which is a very unlikely state of affairs. Edward did not die of Mancini’s chill.’

There is no reason to suppose Philippe de Commynes was better informed than anyone else, being a foreigner who would have relied on hearsay, but his idea of a stroke seems feasible at first glance. However, he was writing soon after his own king died of a stroke, so he might easily have made a subconscious connection.

Collins notes that if a person dies of a single stroke (apoplexy or CVA), he will do so within a matter of minutes. Or, having survived it, he may die from a second stroke, which might indeed occur some 10–12 days later. But strokes were events that would have been well known to mediæval physicians. By contrast, given the reactions of the people at the time, Edward’s death seems to have come as a complete surprise – and Collins finds it quite impossible to believe that no one anticipated Edward might succumb to a second stroke if he had already suffered a first.

That people were taken by surprise again militates against Mancini’s chill, whose symptoms would have been obvious and worrying as they worsened until he died (says Mancini) on 7 April, at least sixteen days after the fishing episode. Crowland asserts a more likely illness of less than ten days. Both were probably present in London at the time but the latter was close to the centre of power, which was then wielded by the queen and her Woodville family. Clearly the official story gave no cause of death, merely a date of 9 April; thus it is possible the announcement was delayed while arrangements were made for administration of the realm.

Collins finds the bewilderment over Edward’s death in itself indicative in an age when no doctor was at a loss for a diagnosis, however far-fetched. The Crowland chronicler is assumed to be a learned cleric and high-ranking government official and, Collins suggests, probably had some education in medicine as part of his background training; yet despite his knowledge and likely access to the physicians attending the king, he was unable to venture a guess at what the fatal disease might have been.

Even Polydore Vergil, the historian favoured by Henry VII, writing his Anglica Historia some twenty-five years later but having full access to most of the State papers of the time, could not be more specific than to say he ‘fell sicke of an unknowen disease’; though Vergil also reported ‘ther was a great rumor that he was poysonyd’.

This is often discounted on the grounds that by the time Vergil was writing, sudden deaths in noble or princely families often gave rise to suspicions of poisoning. However, this scarcely seems a convincing argument. Poisoning was not, after all, a sixteenth-century invention.

Edward was not immune to assassination attempts. One at least is recorded, from which he escaped thanks to a warning given at supper by Sir John Ratcliffe, later Lord Fitzwalter. Whatever the source of the poisoning rumour, Vergil himself did not leap to it as a conclusion: his view was that the cause of death was unknown.

Yet another writer from France, Jean de Roye (misnamed Troyes), whose date of writing (1480s) means that he was commenting on contemporaneous events, believed that Edward died of ‘une apoplexie’ or perhaps, as some people said, he was ‘empoisonné du bon vin’, given to him by Louis XI. We encounter the poisoning theme again in the writings of the English Tudor chronicler Edward Hall, published in the mid-sixteenth century, which contained an agglomeration of material mostly culled from other writers. Hall ran through a number of possibilities: Edward’s sickness was due either to melancholy, anger at the French King, a surfeit, a fever, a ‘continuall cold’ or, as some suspected, poisoning.

In his examination of the few known facts, Richard Collins takes into account this surprise and general bewilderment. Thus he rules out slow-building effects such as those of debauchery (e.g. venereal disease), or drink or obesity, to which the chroniclers make reference. Edward was still a very active and hard-working king, and although his fitness was beginning to be over-taxed by his habits of excess, he appears to have shown no characteristic signs of gradual mental or bodily degeneration. Mancini describes him as ‘a tall man and very corpulent, though not to the point of disfigurement’, so there is no suggestion that he was morbidly obese. Indeed, Mancini adds that he was fond of ‘displaying how impressive he was’ to onlookers.

We know that, in accordance with tradition, his body was displayed in an almost naked state to the view of the nobles and clergy. Since nothing untoward was noted, Collins eliminates violence or infectious diseases that would have left outward signs, any non-infectious conditions that also mark the body, and diseases that cause noticeable wasting of tissue. Appendicitis is also dismissed: given the diet of the time, this is ‘so remote as to be almost impossible’.

One suggestion that crops up regularly is pneumonia, whether in its common or more exotic forms, or as an attendant illness or complication. The problem with pneumonia is that this lung infection, with its tell-tale signs of congestion, fever, and coughing up of characteristic sputum, would have been recognized from long experience and given cause for severe alarm. It does not square with the Crowland chronicler’s comment about ‘no known disease’.

In the course of eliciting opinions from some thirty colleagues in the large provincial hospital where he worked at the time, Richard Collins was careful to disguise the identity of the patient. He received no suggestions that fitted the case, except one: poisoning by arsenic, dispensed not as a series of small doses over time, but as an isolated dose or possibly two (arsenic is tasteless and odourless). This was put forward by no fewer than three highly experienced individuals. Collins found the theory convincing:

Heavy metals such as arsenic, antimony and mercury when administered cause death either slowly or quickly, according to the dose. They leave no signs that would be obvious to the men of 1483; and you would, of course, be perfectly healthy up to the time you swallowed the first dose. Poisoning fits; and I would suggest that, out of all the possible causes of Edward IV’s death, it is the only one that fits all the known facts.

As soon as one has a poisoning theory, of course, one needs a murder suspect or conspiracy. Most people would not immediately leap to suspect Edward’s consort, Queen Elizabeth (née Woodville): it would appear foolhardy in the extreme for a queen to do away with a powerful and successful king, especially when he had been her family’s principal meal-ticket for nineteen years. However, there are two considerations that work in favour of the hypothesis.

First, after nearly twenty years of marriage (and being already five years older than Edward), Elizabeth would undoubtedly have lost many of her charms for the king. Her place in the lustful Edward’s bed was frequently supplanted by mistresses, and as a mediæval forty-five-year-old having survived ten pregnancies, it would not be surprising for her to fear being relegated to a position of obscurity. Her latest matrimonial humiliation had come at the hands of Elizabeth Lambert (Mistress Shore, later erroneously named ‘Jane’), who occupied a position of particular favour at Court. For a neglected and probably disgruntled wife, the end of her influence with the king might have been staring her in the face.

Although there is sweetness in revenge, a more practical motive on Elizabeth’s part might have been to remove the crown from the head of a dangerously bored husband and place it on that of a doting son. The twelve-year-old Prince of Wales, Edward, had been brought up as a Woodville, surrounded by Woodville handlers at his residence of Ludlow Castle in the Welsh Marches, and governed and educated by his mother’s brother Anthony, Earl Rivers. Elizabeth was a woman of character who had built an empire for herself and her family since marrying the king: she certainly had the prescience to instil in her son the right attitude of family loyalty. By precedent, government by a protectorate and council would be expected while he was too young to rule; but during these last years of his minority he might, at a stretch, start participating in his own reign, in which the queen and her family could look forward to considerable influence.

Though evidence is lacking, unsurprisingly, for a relationship grown cool, Paul Murray Kendall suggests that in Edward’s deathbed codicils he replaced Elizabeth as an executor of his will. By contrast, in 1475 he had loaded this in her favour, appointing her his foremost executor and not only ensuring that her personal property remained at her own disposal, but also giving her powers to divide his chattels between herself and their sons.3 In 1483, far from being foremost, she was not even mentioned on the list of executors who met to prove the king’s will.

There is other evidence that things in early 1483 were not proceeding in a way that would benefit Elizabeth’s best interests. There was the threat of more expensive and distracting wars with Scotland, for example; a bottomless pit into which the royal treasury was being emptied. Not for nothing was she one of the leading opponents of the Scottish campaigns. And now, in his latest Parliament, Edward had announced his intention to embark upon an even more expensive war against France, for which the entire kingdom would bear a heavy financial burden.

Meanwhile, the successful outcome of the Scottish military actions had established Edward’s younger brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester as the man of the hour, bringing him closer to the king’s heart and heaping on him ever more rewards and powers. These would certainly increase as he assumed control of the French campaign. There was a danger here for the Woodville menfolk, since their intimacy with the king relied on consorting in his pursuits of the flesh, of which Richard’s disapproval was well known.

Edward was doubtless proud of his two little boys, but at the ages of nine and twelve they were clearly too young to be his companions or equals. Nor could they be outstanding military commanders, as was Richard of Gloucester, who could be relied upon to carry out the king’s orders and wishes with absolute loyalty and, it would seem, conspicuous success.

Born on 2 October 1452, the youngest of the late Duke of York’s sons, Richard was Edward’s last living brother. He would later ascend the throne as Richard III, and it is about this Richard that our story revolves.

Their father had successfully claimed the throne as his rightful inheritance during the civil unrest under the Lancastrian King Henry VI which came to be known as the Wars of the Roses, but had not lived to be crowned. There had been two other sons who reached adulthood: after Edward came Edmund, Earl of Rutland, killed in battle as a teenager; and after him came George, Duke of Clarence, done to death in the Tower of London five years ago after being convicted of treason. Popular Edward, the eldest, was seemingly endowed with all the necessary gifts to make him the strong and successful ruler that England needed when he ascended the throne in 1461.

Twenty-two years on, Edward IV no longer possessed the astonishing strength and virility that had impressed the world during the first dozen or so years of his reign. Young and vibrant, and over 6ft 2in in height, he had been described as the most handsome prince of his generation.

Richard, ten years younger, was shorter of stature, brown of hair and lean of face. In 1484 two visitors actually described him in writing: the Scottish ambassador complimented him on ‘so great a mind in so small a body’, 4 and the visiting Silesian Niclas von Popplau observed that he was ‘three fingers taller than himself, a little slimmer and not so thickset, much more lightly built and with quite slender limbs’.5 Niclas’s own physique is unknown, but we may perhaps conclude that Richard was sinewy rather than strapping.

The recent dramatic discovery of his grave reveals that he was strong and well muscled, with good teeth. He could have stood 5ft 8½in but for the uncertain effects produced by what we now know was a lateral curvature of the spine (scoliosis) which made his right shoulder higher than his left – giving the lie to Thomas More who said the opposite. Developing after puberty, it would have become visible only gradually, and could scarcely have been striking when clothed or Niclas would surely have noted it. The curvature of scoliosis would manifest as uneven shoulders but not a hunched back (kyphosis). Nor, evidently, did it affect Richard’s famed prowess as a fighting soldier. These realities, together with his sound and straight limbs, must once and for all debunk Shakespeare’s monstrous shambling creature with hunched back and withered arm.

Richard was credited with a keen intelligence; he placed a high value on loyalty and seems to have been capable of inspiring it. Above all else he was his brother’s trusted general. In an age when military achievement was the jewel in the aristocratic coronet, when virtues of chivalry, valour and loyalty were pearls beyond price, Richard gave his brother good reason for pride.

This is not to pretend he was without failings. Undoubtedly he was headstrong in a number of ways, aggressive in pursuit of his own ends, and as acquisitive as any other mediæval younger brother. Perhaps more so in view of his elevation to a royal estate for which he inherited no means of support.

Though modern sensibilities may recoil at the thought, these were times when land, income and status were frequently derived from the downfall of an opponent, often entailing forfeiture by that opponent’s wife and children. Marriages were also routinely contracted with material advantage in mind. Richard had done well for himself on both scores, having been highly rewarded for his services to the king and having made an excellent match with a famous heiress, Anne Neville, daughter of the Earl of Warwick (‘the Kingmaker’).

Through his wife’s inheritance he was fortunate to hold estates in the north of England, in addition to his favourite castle of Middleham which he and Anne made their usual residence. Edward had established Richard, while in his early twenties, as the principal potentate in the unruly north, giving him powers equal to those of a viceroy. Richard adopted a policy of consolidating his holdings there, which speaks of wholehearted commitment and perhaps an affinity for that region. The records of the time also indicate that he worked assiduously at carrying out his powers and responsibilities, pursuing the interests of the local citizenry when petitioned, and adjudicating fairly in disputes even if it meant giving judgement against one of his own employees.

When Edward IV died, Richard was residing in his northern estates. Though he attended the Court when state business required, his duties and home life were concentrated in the North. Some have suggested his absence was due not only to a dislike of the politicking and sensual excess practised at Court, but also to his revulsion at the fate of his brother Clarence, famously executed for treason in 1478 by (supposedly) drowning in a butt of malmsey wine.

The death of Clarence appears to have been a turning-point in many ways, so this is an appropriate moment to examine it here. According to Mancini, Clarence had started off on very much the wrong foot with his in-laws ‘publicly and vehemently inveighing against Elizabeth’s obscure origins, and by making it known that the king, who should have married a virgin, had acted against custom by taking to wife a widow’.

Such accusations, if made, did no more than give voice to a widely-held grievance about Edward’s choice of queen. Elizabeth was a subject and a commoner who brought no financial and strategic advantage as might have been gained by an alliance with foreign royalty. No king since the Conquest, with the sole exception of Henry I, had sought a wife within England. Moreover, Elizabeth’s family had fought against the house of York. Clarence might well have added further objections to Edward’s headlong rush into wedlock, such as its secrecy without consultation or proper formality, and the fact that Edward continued to conceal it for more than four months in the full knowledge of diplomatic approaches being made for marriage into some of Europe’s leading royal families. The deception was still remembered as late as 1483 when Isabella of Castile, one of Edward’s putative brides, declared that she had not forgiven the insult at his hands nearly twenty years earlier.

Much has been made of Elizabeth’s unsuitability as a royal consort, and much has been written saying that she performed her job well, carried out acts of benevolence as befitted her station and was beautiful and fertile into the bargain. These were qualities that suited Edward well, and he certainly made it clear that his wishes were what counted. For most people it was a nine days’ wonder that scarcely affected their lives.

Nevertheless, there were some for whom the mésalliance was keenly felt, and Clarence was one of them. Also among them was their mother, Cecily (‘Proud Cis’), Duchess of York. Cecily’s rage was such that she is reported by Mancini to have denounced Edward as no son of his father and unworthy of the throne. Mancini’s story may or may not be reliable, but as Michael K. Jones comments: ‘In an age when the niceties of position were all-important and the rituals of their observance paramount, Cecily refused to allow the new upstart queen to outrank her. In a startling act of royal one-upmanship, she devised a title of her own and now styled herself Queen-by-Right.’ This was within months of Edward’s marriage being announced.6

But Clarence was not only disliked for sharing these views. Shakespeare’s phrase, ‘false, fleeting, perjur’d Clarence’, aptly describes his career of relentless self-advancement, which involved marrying against Edward IV’s wishes and cementing an alliance with the king’s enemies – both English and French – in the bold expectation of replacing him on the throne. Though temporarily reconciled, Clarence started behaving with extraordinary high-handedness in 1477 and challenging the king’s justice. Edward’s tolerance ended abruptly and he had his brother arrested, tried and condemned for treason.

Domenico Mancini tells the story juicily in his intelligence report; he appears to give us an insight into Woodville thinking when he relates the downfall of Clarence as follows:

The queen, mindful of the insults … that according to established custom she was not the legitimate wife of the king, deemed that never would her offspring by the king succeed to the sovereignty unless the Duke of Clarence were removed; and of this she easily persuaded the king himself. … Accordingly, whether the charge was fabricated or a real crime brought to light, the Duke of Clarence was accused of purposing the king’s death by means of magic spells and sorcerers. On being brought to judgement, he was condemned and executed. At that time Richard, Duke of Gloucester, his feelings moved by anguish for his brother, was unable to dissimulate so well but that he was heard to say that one day he would avenge his brother’s death. Thereafter he very rarely went to court, but remained in his own province. By his good offices and dispensing of justice he set himself to win the loyalty of his people, and outsiders he attracted in large measure by the high reputation of his private life and public activities. Such was his renown in warfare that whenever anything difficult and dangerous had to be done on behalf of the realm it would be entrusted to his judgement and his leadership. With these arts Richard obtained the goodwill of the people and avoided the hostility of the queen, from whom he lived far distant.

Later in his report Mancini refers again to the Woodvilles being guilty of Clarence’s death, in fact he makes two further such references. In the first he says, ‘They had to suffer the accusation by all, of responsibility for the Duke of Clarence’s death.’ In the second he claims the Woodvilles feared that if Richard ‘became the sole head of government, they who suffered the accusation of Clarence’s death would either undergo capital punishment or at least be ousted from their high degree of prosperity’. Throughout his report, their guilt in the Clarence affair is a given.

Interestingly, the Crowland chronicler writes that during that fatal year of 1477 Clarence also started refusing to accept food and drink at Edward’s palace. Taking this with the narrative from Mancini, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that it was from his Woodville in-laws that Clarence perceived the threat.

We need not give credence, by the way, to Richard of Gloucester’s supposed vow of vengeance, said by Mancini to have been overheard (by an unknown source) in 1478. Mancini did not hear it himself, nor would it have come from Richard’s circle: even Clarence’s biographer, the staunchly anti-Richard Michael Hicks, maintains it is clear from Mancini’s text that he knew none of those around the duke.

Perhaps it was a story whispered by those who witnessed Richard’s dismay at his brother’s demise, but frankly we have no evidence to tell us that Richard’s inner feelings were anything but amicable towards the Woodvilles. In his capacity as an administrator and arbitrator, they asked him on occasion to act as executor or to adjudicate in a dispute, which would form a normal part of his workload. One might view the various members of royalty as co-directors of a company, where personal feelings have no relevance. Richard’s sense of loyalty to the king would preclude behaving unprofessionally, and so would a lively sense of self-preservation.

The views of historians who believe Richard did hold the Woodvilles responsible for eliminating Clarence may be coloured by hindsight; for although there is corroboration that he had reached this conclusion in September 1484, he had by then occupied the throne for more than twelve months during which he would have learnt many previously unknown truths. He revealed his knowledge in overtures of friendship to the Anglo-Irish Earl of Desmond. In doing so, he drew a remarkable parallel between Clarence’s death and that of the earl’s father, the 7th Earl, who had been executed in suspicious circumstances during the reign of Edward IV. In Richard’s written briefing to the ambassador who carried his letter, he not only stated in unequivocal terms that the late earl’s fate amounted to murder under the pretence of law, but also proffered an invitation to Desmond to seek punishment for whomsoever was responsible. One can scarcely miss the implication that Richard felt the same perpetrators were involved in both executions.

The relevant part of the briefing document reads as follows (it is addressed to the ambassador and refers to Richard and Desmond in the third person; the emphasis is mine):

… albeit the Fadre of the said Erle, the king [Richard] than being of yong Age, was extorciously slayne & murdered by colour of the lawes within Irland by certain persones then havyng the governaunce and Rule there, ayenst alle manhode Reason & good conscience, Yet notwithstanding that the semblable chaunce was & hapned sithen within this Royaulme of England, aswele of his Brother the duc of Clarence, As other his nighe kynnesmen and gret Frendes, the kinges grace alweys contynuethe and hathe inward compassion of the dethe of his said Fadre, And is content that his said Cousyne, now Erle, by alle ordinate means and due course of the lawes when it shalle lust him at any tyme hereafter to sue or attempt for the punysshement thereof.7

In 2005, further support was published in research by John Ashdown-Hill and myself into the mystery surrounding the execution of the 7th Earl of Desmond, Thomas Fitzgerald, which occurred in 1468.8 Desmond, a close friend and ally of Edward IV and his father, was charged with treason on flimsy grounds by the then Lord Deputy of Ireland, John Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester. The arrest, verdict and execution all took place in Drogheda within the space of eleven days, ensuring he had no time to appeal for clemency. The king later pardoned Desmond’s two co-accused who were lucky enough to escape and make their way to England, which lends credence to the supposition that had the earl managed to appeal in the same way, the king would have done no less for the man who was his family’s staunch friend.

A number of sources vouch for Edward’s surprise and chagrin when he learned of Desmond’s execution, and generous reparations were subsequently made to the late earl’s family. Other sources add evidence that two of Desmond’s young sons, both aged under thirteen, were gratuitously executed by Tiptoft at the same time as their father.

The most controversial aspect of the case is one which, understandably, seems to have been less widely known at the time. It was the belief of the Fitzgerald family that the 7th Earl’s fate was brought about by Queen Elizabeth through Tiptoft as her agent; her motive being that Desmond, when pressed by Edward IV for a reaction on the occasion of his marriage, had insulted her by stating his view that the king had ‘too much abased’ his princely estate ‘in marrying a lady of so mean a house and parentile’. Seeking his head in retribution, the queen sent letters of instruction directly to Tiptoft arranging Desmond’s arrest. A supporting document states that the earl’s fate was intended as a warning to others who would speak slightingly of the queen – a telling point, since it answers the important question of how knowledge came to his family that she was behind it all. She wanted them to know.

This knowledge had evidently reached Richard’s ears, because the briefing he gave to his ambassador in 1484 indicates that he knew who had engineered the atrocity: those who had the ‘governance and rule’. With the present earl now given the opportunity to pursue the perpetrators, obviously this could refer neither to Edward IV, who was many months dead, nor to John Tiptoft, who was many years dead. Who else had governance and rule in 1468? And who also had the power to arrange the destruction of Clarence in 1478?

Some commentators claim that Richard’s words to his ambassador constitute mere compliments and platitudes, which is a reading my co-researcher and I would challenge: on the contrary, they are remarkably frank and decidedly controversial.

Then there is Richard’s strange reference to a similar fate suffered by ‘other nigh kinsmen and great friends’, which may perhaps be dismissed as the kind of meaningless tautology seen in formal communications of the time. However, it must be remembered that this document was not itself a formal letter to Desmond; it was strictly a briefing document expounding to Richard’s ambassador the gist of what he wanted him to convey by word of mouth. It could be that in the course of dictation Richard called to mind other deaths which for us, after many intervening centuries, have lost all significance but which perhaps seemed to him to smack of Woodville contrivance. For example, has anyone ever queried the whereabouts and circumstances of the death of his young cousin, George Neville, which for reasons of inheritance had an enormously negative impact on Richard’s prospects? Or the death of Henry, Earl of Essex and Treasurer of England, which interestingly coincided with that of Edward IV? And if there is any truth in the assassination theory which opened this chapter, might Richard not even have had his brother Edward in mind? After a gap of 500 years, such questions cannot be answered, yet this is no reason for dismissing them out of hand.

2

The Politics of Power

After Clarence’s death it was remarked that Edward IV underwent a change of character, growing more bitter, avaricious and despotic. Matters worsened when in 1482 England’s ancient enemy, France, coolly reneged on a treaty of seven years standing. Doubtless Edward’s wrath was felt by all those around him.

If Edward’s relationship with his queen had soured, that with his powerful Lord Chamberlain, William, Lord Hastings, may have gone the same way.

Hastings had been a councillor and intimate companion of the king for the past twenty years. A decade older than Edward, he was about the same age as other senior councillors such as Thomas, Lord Stanley, or Richard, Earl of Warwick (‘the Kingmaker’) who had helped him win the throne. A leading courtier and commander of the Calais garrison, Hastings had shared Edward’s triumphs and adversities over the years, and equally had shared and encouraged his vices. In return he had been showered with rewards and offices, not the least being his appointment as Captain of Calais in 1471.

From this appointment a dispute blew up between Hastings and the Woodville family, since Elizabeth’s brother Anthony, Earl Rivers, had been appointed to that same office in June the previous year. Edward, with typical insensitivity, failed to understand its significance to Anthony whose father and grandfather had held it before him. Not only was it the sole conspicuous office ever held by his Woodville forebears prior to his sister’s elevation, it had now become, for the second time, a cause of Woodville humiliation. The first time was in 1460 when the Lancastrian Woodvilles had been tasked by Henry VI with recapturing Calais from the house of York. Instead they had been bested and held there as helpless captives while the Earl of Warwick and his cousin Edward, Earl of March, publicly berated and belittled them as upstarts and social parvenus. Now, exactly ten years later, that same Edward of March was King Edward IV and had calmly removed the Calais office from Anthony and given it to Hastings.

Long before Hastings began feuding with the Woodvilles, his relationship with Elizabeth predated her marriage to Edward in May 1464 and suggests his involvement in bringing it about. On 13 April 1464 – eighteen days before the king’s notorious secret wedding – Hastings entered into a contract with her which promised, inter alia, one of her two sons in marriage to a daughter or niece of his. This was in return for his intercession to ensure those sons inherited certain lands which her late husband’s family, the Greys, were contesting. The fact that she turned to Hastings for help, rather than Edward, reinforces the notion that no expectation of marriage with the king existed even as late as mid-April.

One cannot help wondering what possible interest the king’s powerful chamberlain could have had in allying his family with Elizabeth and her sons. Although the Woodvilles were well-connected gentry, the boys were merely the offspring of a recently-made knight and the grandsons of a baron. Was it Edward’s idea? Was he attempting to buy his way into her bed with a marriage alliance that would bring her family right into his inner circle, with all the patronage that entailed? If so, he doubtless underwrote Hastings’s side of the bargain with the promise of a handsome payoff.

That Hastings was not entirely enamoured of the arrangement is suggested by the hard bargain he struck, and by the fact that in August that year, before Edward was prepared even to acknowledge Elizabeth as his wife, he granted Hastings the wardship of her elder son, Thomas. This smacks of an attempt to kill two birds with one stone: compensating his chamberlain for services rendered while simultaneously covering up the marriage, since no one would expect Edward to give away the wardship of his own stepson. The right of wardship under feudal law conferred control of a minor heir – and his income – until he came of age; often also included was the right of marriage which allowed influence as to whom the heir would wed.

Of course, once Elizabeth was revealed as Edward’s queen, all of this was stood on its head: the marriage into the Hastings family never materialized, and doubtless Edward found a way to replace the modest income from the wardship. But the early connection between Hastings and Elizabeth is tantalizing.

At this rate we may reasonably take the supposition further, and ask ourselves whether one of Hastings’s uses was perhaps as Edward’s procurer. A man in the king’s position had less freedom of movement than any of his subjects and less opportunity to make his own conquests. Was it Hastings who arranged private meetings with suitable ladies when Edward was still a bachelor, and did that role continue after he was married? If so, was it an arrangement the queen deeply resented, or did she tolerate it in the knowledge that it was the price she had to pay?

Hastings has usually been portrayed as a bluff military man, loyal to Edward through thick and thin, in wartime his trusted general, in peacetime hunting, carousing and wenching at his side. Mancini tells us that, even in his latter years, ‘in carnal lust Edward indulged to an extreme’, and that Hastings was ‘an accomplice and participant in his private gratifications’.

He was, however, a great deal more cunning and self-serving than this suggests. For example, from 1461 he received an annual pension of 1,000 crowns from Charles, then heir to the Duke of Burgundy, for reasons unknown. Maybe it is significant that it was Hastings who helped cement England’s alliance with Burgundy by negotiating Charles’s marriage, in 1468, to Edward’s sister Margaret of York. He was still receiving the same annuity when he accepted a 2,000-crown pension from Charles’s enemy, Louis XI of France, in 1475. Hastings’s adroitness in arranging that this pension be ‘deniable’ was admired even by Louis and his councillor, Philippe de Commynes.

Hastings showed himself very much his own man when, between March 1477 and January 1480, he took reinforcements to Calais against Edward’s express orders. This was in response to a call to Edward for help by his sister Margaret, recently widowed on the death of the Duke of Burgundy; an appeal to chivalry which was refused by Edward but apparently accepted by Hastings and Richard of Gloucester. This action, and Richard’s support in it, would have greatly enhanced Hastings’s military reputation in the eyes of the Calais garrison. It might indeed have elevated his position to such an extent that Edward perhaps began to suspect Hastings of having his own agenda, together with the means to pursue it, in the foreign and domestic politics of the day.

A relationship may easily go sour when a subject appears to have a will of his own, especially when he shames the king and shows him wanting in chivalry. Did Hastings feel disillusioned by the king’s actions of late, and had he felt the sting of his tongue too often? Did Edward resent Hastings’s continued abilities as a military commander at age 50, when the king at 38 was too gross (or ‘otherwise engaged’) to take horse at the head of his troops?

Hastings’s feud extended to the queen’s eldest son Thomas, Marquess of Dorset, one of three Woodvilles detested as being the king’s ‘panders who aided and abetted his lustfulness’, says Mancini, who adds that Hastings ‘was estranged and at mortal enmity [with Dorset] on account of the mistresses they had abducted or seduced from each other’. Mancini attributes an important factor in the turbulent events that followed ‘to have derived its origin in the quarrel of these two’. It even embarrassed the king himself in 1482 when Hastings crossed a line by intimidating a man named John Edward to make false accusations against Rivers and Dorset. The king assembled and personally presided over a very full Council meeting where John publicly confessed and recanted.

Perhaps Edward lost patience with Hastings and his feuds, or perhaps he was somewhat sickened by the unedifying spectacle of his ageing chamberlain vying with Dorset for the favours of youthful paramours. Maybe Hastings even overstepped the mark with some mistress that Edward considered his own property. The patronage of kings is notoriously capricious.

The significance for Hastings of a once-great friendship gone bad would have had far-reaching consequences. As the king’s Lord Chamberlain, he was a natural channel for the demands made on royal patronage; he was in an ideal position to strike lucrative bargains in return for his influence. Now imagine if Edward began to refuse Hastings’s requests. Perhaps there were words exchanged which signalled an end to their days of