Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

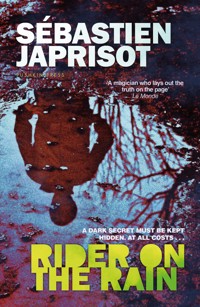

He is suddenly and monstrously there, and his mask disguises nothing . . .The bus never stops in Le Cap-des-Pins. Not in autumn, when the small Riviera resort is deserted. Except today, when a man with a red bag and a disconcerting stare steps out into the rain. His arrival will throw the life of young housewife Mellie Mau into disarray. After surviving a horrific attack, she has a dark secret to hide. But a stranger at a wedding, the enigmatic American Harry Dobbs, is determined to get the truth out of her, leading her into a game of cat and mouse with dangerous consequences ...A cool, stylish and twisty thriller from cult French noir writer Sébastien Japrisot.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 166

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sébastien Japrisot was a prominent French author, screenwriter and film director, and the French translator of J. D. Salinger. He is best known for A Very Long Engagement, which won the Prix Interallié and was made into a film by Amélie director Jean-Pierre Jeunet. One Deadly Summer won the Prix des Deux Magots in 1978 and the film adaptation starring Isabelle Adjani won the César Award 1984. Rider on the Rain was also made into a film starring Charles Bronson. Born in Marseille in 1931, Japrisot died in 2003.

Linda Coverdale has a Ph.D. in French Studies and has translated over eighty books, including Japrisot’s A Very Long Engagement and works by Marguerite Duras, Jean Echenoz, Emmanuel Carrère, Patrick Chamoiseau, Georges Simenon and Roland Barthes. A Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, she has won many awards, including the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and several Scott Moncrieff and French–American Foundation Translation Prizes. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Praise for Rider on the Rain:

‘Japrisot writes with warmth and has a gift for rendering almost every character instantly likable’New Yorker

Praise for The Sleeping Car Murders:

‘A strongly plotted story of murder with a clever ironical ending. For a first novel it is remarkable’

Daily Telegraph

Praise for One Deadly Summer:

‘The most welcome talent since the early Simenons’New York Times

Praise for The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun:

‘Utterly captivating, this is a perfect diversion for a sunny afternoon’The Guardian

‘Detailed, substantial, full-blooded. It combines huge intellectual grasp with fascinating narrative, strong grues, fine writing and an unforgettable protagonist … a superb achievement’The Times

‘A riddle as captivating as it is terrifying’Christian House

Rider on the Rain

Also available from Gallic Books:

One Deadly SummerThe Lady in the Car with Glasses and a GunThe Sleeping Car MurdersTrap for Cinderella

Rider on the Rain

SÉBASTIEN JAPRISOT

Translated from the French by Linda Coverdale

Pushkin Press

A Gallic Book

First published in France as Le Passager de la pluie by

Éditions Denoël, 1992

Copyright © Éditions Denoël, 1992

English translation copyright © Linda Coverdale, 1999

First published in Great Britain in 1999 by the Harvill Press

This edition first published in 2021 by Gallic Books, 59 Ebury Street, London, SW1W 0NZ

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781805334231

Typeset in Adobe Garamond by Gallic Books

Printed in the UK by CPI (CR0 4YY)

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her, and to wonder what was going to happen next.

Lewis CarrollAlice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Contents

Tuesday, 5 p.m.

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Wednesday, noon

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Thursday, 10.30 a.m.

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Friday, 10 a.m.

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Saturday, 8 a.m.

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Tuesday, 5 p.m.

1

Apeal of thunder, a grey river spattering in a downpour, a horizon blurred by autumn. And then the wheels of a bus send up great glistening sprays of water, and the river becomes a road running the length of a desolate peninsula, somewhere between Toulon and Saint-Tropez.

From quite high up, well above the housetops, we watch the vehicle – which is grey, like the road – entering a deserted seaside resort: Le Cap-des-Pins. As we can see, it is not even a town, actually, but a single long street that follows the curves of a sandy beach battered by the chilly Mediterranean.

There is no one in the street. There does not seem to be anyone on the bus. There is only the rain, falling steadily and heavily, and the movement of massive waves breaking on the shore.

At the end of the street, a large crossroads: a supermarket, closed; some summer shops, also closed. One road heads inland through vineyards, while another, edged with streaming palm trees and shuttered houses, follows the coastline.

It is at this crossroads that the bus stops.

From the other side of the street, behind a window lashed by sheets of rain, a young woman watches the bus pull up.

She is blonde, pretty, wearing a white turtle-neck sweater. White suits her. She is twenty-five years old. She has a sensible haircut, a sensible face, a sensible life, and doubtless, in her heart, dreams as crazy as everybody else’s, but she has never told them to anyone.

She is Mélancolie Mau, known as Mellie, and later on someone will call her ‘Love Love’. Her expression, her bearing, even her temperament, are in perfect accord with her real first name.

At this moment, however, as she looks through the window, she presses a finger of her right hand against her lips, allowing us to notice the one thing about her that belies her serene and well-groomed appearance: nails bitten to the quick.

A woman’s voice is suddenly heard behind her, loud and incredulous.

‘Mellie? … Is that the bus from Marseille stopping here?’

‘Yes, Mummy.’

‘Certainly not. That bus never stops.’

She speaks with the assurance of someone who would never permit even obvious facts to change her mind. Mellie does not reply. Besides, the bus has halted for only a few seconds. It is already pulling away from the kerb.

The room where the young woman watches from the rain-streaked window is somewhat lower than the street, so that she sees the bus from the side and on a level with the wheels.

Only the driver is on board, but as the heavy vehicle moves away, it reveals a passenger she had not seen get off the bus, standing motionless in the rain.

He is quite tall, with a shaven head, and seems uncertain, like someone arriving there for the first time. He is wearing a grey raincoat and carrying a red travel bag – one of those canvas overnight bags given away by airlines.

The woman with Mellie calls out again.

‘What are you looking at? Is there a passenger?’

‘Yes, Mummy.’

‘Did he come in on the bus?’

As the question is not worth answering, Mellie does not reply. It is her mother who answers her own question, peremptorily.

‘Certainly not. No one ever comes here on that bus.’

Mellie gives a slight shrug, still watching the stranger across the street. Before turning away from the window, she replies amiably, ‘Then he must have ridden in on the rain.’

Outside, the man hesitates, paying no attention to the raindrops running down his face. He looks at the sea. He even takes a few steps in the direction of the departed bus. And then, thinking better of it, he heads back towards the centre of the village.

He walks slowly along beneath the dripping pine trees, staring straight ahead of him, like someone who has no idea where he is going, and his red bag is the only spot of bright colour in the driving rain.

2

A white sports car going at breakneck speed skids suddenly and horribly out of control on a dark road. After turning over three times, the car comes to rest against a woman’s hand blocking its way – a real hand, larger than the car.

This hand picks up what was only a toy on an electric track and sets it down on one side.

In the harsh glare of an overhead light, the mother of Mellie Mau lights a fresh cigarette from the fag-end of the one she is just finishing.

A woman still youthful and elegant, she has a nervous, affected manner. She is one of those people who, hating everything, hate themselves. Her name is Juliette.

She is sitting at an immense table on which is mounted a racetrack for miniature cars, with bridges, zig-zags, and steeply banked turns. Although it is not yet dark outside, the spotlights above this table have been turned on.

Mellie Mau is seated on the other side of the table and watches her mother stub out her cigarette in a full ashtray.

MELLIE: That’s the third one in ten minutes.

JULIETTE: I smoke so that you’ll have something to say to me.

She almost always speaks in a sharp, even disagreeable tone, but without raising her voice or taking any notice of other people’s reactions.

She is busy checking her cars. She places the damaged ones inside a large cardboard box sitting open beside her.

MELLIE(in a hurry to leave): I have to go and pick up my dress.

JULIETTE: I’ve finished.

They are alone in a vast basement with an arched ceiling – a kind of funfair for summer visitors, the sort of place found everywhere along the coast: a bar with rows of bottles arrayed behind the counter, a few slot machines, two pinball games, and a jukebox. But it is the four bowling lanes of pale varnished wood, superbly maintained, that take up most of the room.

The amusement hall, which is called ‘Chez Juliette’, is closed until Easter. All the windows are tightly shuttered, except for the panes in the door opening onto the street.

Juliette tests one last car by lifting its back wheels off the track and accelerating to top speed. She places it among those in good working order.

JULIETTE: There are six that need to be repaired. What’s wrong with that one?

She reaches across the racetrack for the red car Mellie Mau is holding. The young woman leans out beneath the spotlights to hand it to her.

MELLIE(standing up): It flips over.

JULIETTE: Certainly not. You never know how to do anything!

Without answering, Mellie picks up a white raincoat draped across the seat of a chair and puts it on.

Her mother walks barefoot across the bowling lanes and steps behind the bar. She pours herself a whisky. Neat, no ice.

Mellie watches her but says nothing. She closes the box of cars to take it with her.

JULIETTE: Well, say it – I drink too much!

MELLIE: Mummy, you drink too much.

JULIETTE: I drink to forget.

Looking grim, she takes a big gulp of her drink.

MELLIE(wearily): To forget what?

JULIETTE: That men are bastards.

In her white raincoat, rainhat, and matching boots, Mellie heads towards the door, carrying the large box under one arm.

JULIETTE: Those damaged cars, when will you take them in to be fixed?

MELLIE: Day after tomorrow.

JULIETTE: Why not tomorrow?

MELLIE: Tomorrow, I’m going to a wedding.

JULIETTE: You mean your husband doesn’t want you to see me.

MELLIE: He doesn’t want me to come here; that’s not the same thing.

Opening the door, she stands for a second before the pelting rain. When she turns back to her mother, her face is already wet.

MELLIE: Besides, you’re invited tomorrow, too. Why don’t you just come?

JULIETTE(without looking at her): I went to mine, and that was enough, thank you.

A faint sigh, a nod, and Mellie leaves.

MELLIE: Bye, Mummy.

It is only after the door has closed that Juliette looks up and replies.

JULIETTE(with unexpected tenderness): Bye, darling.

She downs the rest of her drink in one swallow.

3

Dashing through the rain with her big cardboard box, Mellie Mau reaches a car parked in a lay-by on the other side of the street, facing the sea.

It is a midnight-blue Dodge Coronet station-wagon, luxurious, but muddied by the bad weather.

Mellie shoves the box into the boot and hurries to get behind the wheel.

A moment later, she is driving down the long street of Le Capdes-Pins.

She drives slowly, and the size of the car, as it rolls smoothly and silently along, reinforces that impression. The only sound is the splashing of the rain.

Behind the to-and-fro of her windscreen wipers, Mellie passes through a deserted village. Only a bar-tabac is open.

It is in front of this bar that the man from the bus is standing with his red bag.

The lights inside the bar have already been turned on for the evening, and some customers are playing cards. But the stranger has not gone inside to take shelter. He is standing absolutely still on the pavement, in the rain.

As she drives by, Mellie Mau glances at him through the side window and their eyes meet. He has the eyes of a statue, silent and grave, as impassive as his rugged face.

She cannot help looking back at him in her rear-view mirror. She sees that abruptly, but without haste, he begins walking again, in the direction that she is going. He is still carrying the red bag.

She thinks no more about him.

Further on, where the road leaves the village, another window is lighted. The shop sign says, NICOLE BOUTIQUE. Mellie stops the Dodge, and, slamming the car door behind her, runs into the shop.

A few moments later, a curtain of heavy beige material is pulled aside, revealing the young woman getting undressed. Three mirrors reflect her image as she begins peeling the turtle-neck sweater off over her head.

She is in the changing cubicle of one of those shops where bathing suits, dresses, trousers, blouses, and whatever else can be sold to female tourists during the summer months, all pile up in a heap on five square metres of thick carpet within four walls of white pebbledash.

The hand drawing back the curtain on Mellie Mau belongs to Nicole, the proprietor and sole employee of the establishment, and Mellie’s longtime best friend.

Nicole brings over a dress on a hanger. It is a white cocktail dress with a flared skirt, and it fastens from top to bottom with a row of crystal buttons.

Nicole is the same age as Mellie, or only slightly older, but her years of experience count for double.

She is a good-hearted girl who tries to be cheerful and is sometimes sad; she is attractive, intelligent, sensitive, and she would make some man – as is said of girls who have not yet had to prove it – very happy. In a word, she is single.

She hangs the white dress inside the cubicle, and talks to Mellie whilst helping her wriggle out of the turtle-neck.

NICOLE: They can go to the Moon all they want, and to Mars, and to Wherever, but they still won’t find anybody up there. Anywhere. So what’s the point?

MELLIE(freed from her sweater): Did you get the bread I wanted?

NICOLE: Yes, I got your bread. It’s over there.

She moves away from her friend, who is taking off her skirt. As Mellie carefully folds up her clothes, she studies the white dress hanging in front of her.

MELLIE: You don’t think this dress is a bit short?

NICOLE(crisply): No.

MELLIE(taking off her boots): Give me your shoes so I can check.

Nicole steps out of her high-heeled shoes and, with one bare foot, pushes them over to Mellie, who slips them on.

NICOLE: That husband of yours doesn’t like short dresses?

MELLIE: Not on me he doesn’t.

She undoes the buttons of the dress on the hanger, one by one, sometimes stopping to examine the seams.

NICOLE: When’s he coming home?

MELLIE: Tony? Tonight.

NICOLE: He’s supposed to bring me back a record, from London. You’ve no idea … slin-ky!

Reflected in three mirrors, Mellie gives a little laugh as she takes the dress off the hanger.

MELLIE: What’s that like, a ‘slinky’ record?

Nicole claps her hands softly and hums a slow rock tune. She does a few sensual dance steps for her friend out in the open space of the boutique.

Doing this, she moves away from the cubicle. The beige curtain is only half closed.

Mellie Mau, undressed, suddenly notices in a mirror that there is no longer a screen between her and the shop window and that a man is standing on the pavement, motionless, watching her.

She whips around.

The incident would be a brief and unimportant one, were it not for the steadiness of the man’s gaze. It is the stranger from the bus.

He does not turn away or walk off like a voyeur caught in the act. Standing there in his soaking raincoat, holding his red bag in his arms, he stares unblinkingly at Mellie Mau with eyes that devour her whole, yet not a flicker of expression crosses his face.

She is transfixed, as if mesmerized by his own fascination.

All she would have to do is pull the curtain closed. For one, two, three seconds, locked in a look that lasts forever, she is incapable of doing this. In fact, she discovers what is most paralyzing for someone like herself: the abnormal. This man is abnormal. She sees it in his eyes, she senses it, she knows it.

But there is something else. She is not naked, or simply half-undressed. She is wearing an outfit – stockings, suspender belt, pants, bra, and Nicole’s damned high heels – that suddenly takes on, in spite of her having worn such things for years, a disturbing and almost culpable reality: it is because of this outfit that she, Mellie Mau, is fascinating to an abnormal man. And she sees that in his eyes as well.

Three seconds pass during which Nicole can still be heard humming, unaware of what is happening.

And then Mellie yanks the beige curtain shut, erasing everything.

4

Dusk.

Wearing her white hat, at the wheel of the Dodge, Mellie hums Nicole’s rock tune to herself.

It is still raining. The car’s headlights flash across pine trees, a downhill bend, grapevines, jumbled fragments of the road the young woman must take to get home.

Her house is a few kilometres from the village. Barely wide enough for two cars to pass abreast, the road winds up to the top of a hill overlooking Le Cap-des-Pins. There are a few villas scattered among the trees, but most of them have been closed up for the winter.

Without slowing down, Mellie Mau turns into a gravel drive, and with the confidence born of long habit, steers the car through a garden in which oleanders are still blooming, battered by the rain.

She stops with a great squeal of brakes in front of a white house – a rather sprawling, multi-level affair, with a roof of curved tiles.

Turning off her headlights, she picks up from the seat beside her a large pain de campagne and a clothing box with NICOLE emblazoned on it, then dashes the few steps to the house, slamming the car door behind her.

Shortly afterwards, a bedside lamp with a red shade is turned on.

It is Mellie Mau, entering her bedroom on the first floor. She has already taken off her hat, raincoat, and boots downstairs.

She opens the clothes box on her bed, unfolds her new dress, smoothens it out on the bedspread, and studies it thoughtfully, chewing on a thumbnail.

On the ground floor, a clock begins to strike seven.

At the second chime, Mellie turns and moves briskly across the room in her stockinged feet.

It is a room with several windows, cosy and feminine, decorated in white and pastel colours.